Towards Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes: Materials and Challenges for Water Electrolysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Principles

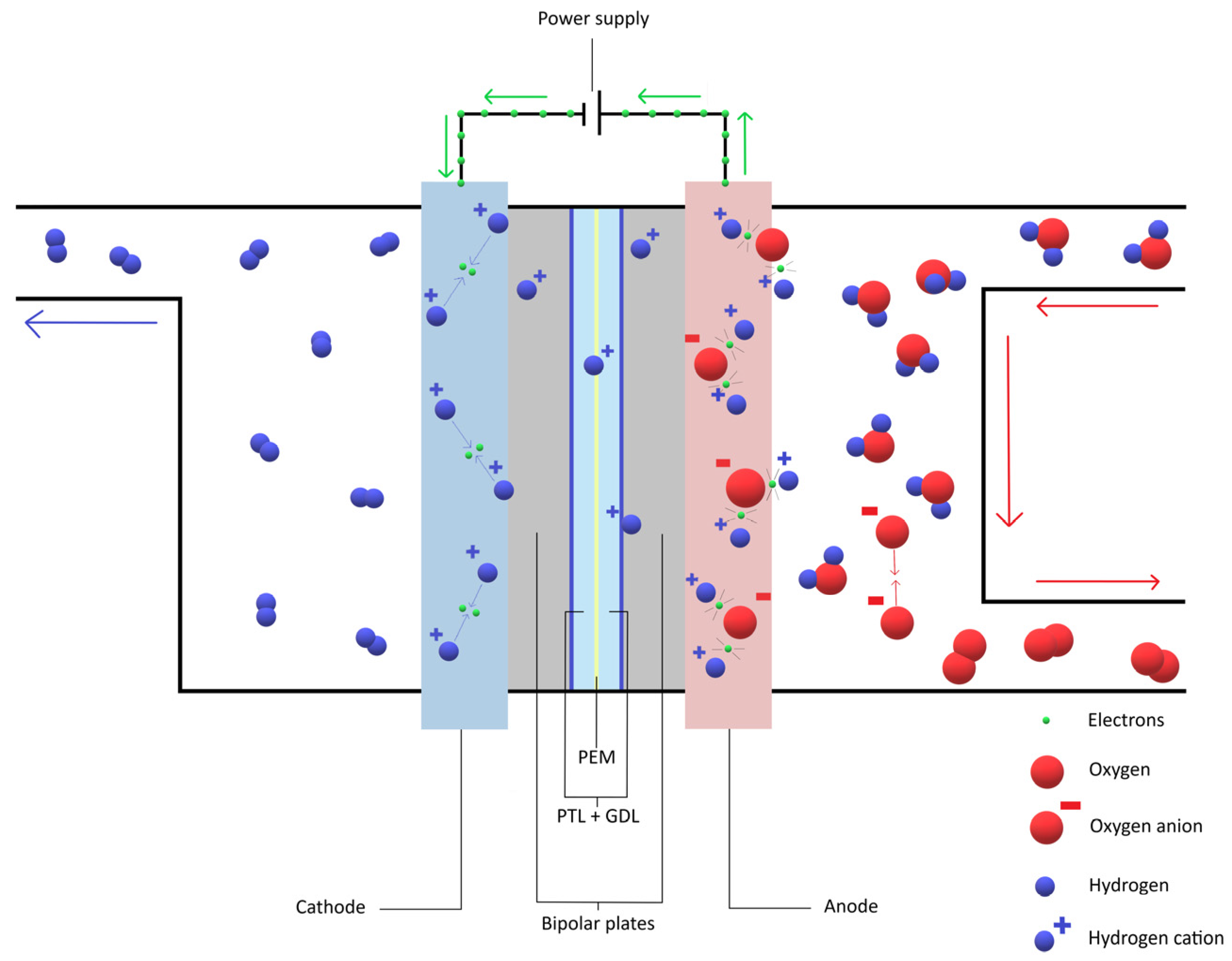

2.1. Water Electrolyzer with Proton Exchange Membranes

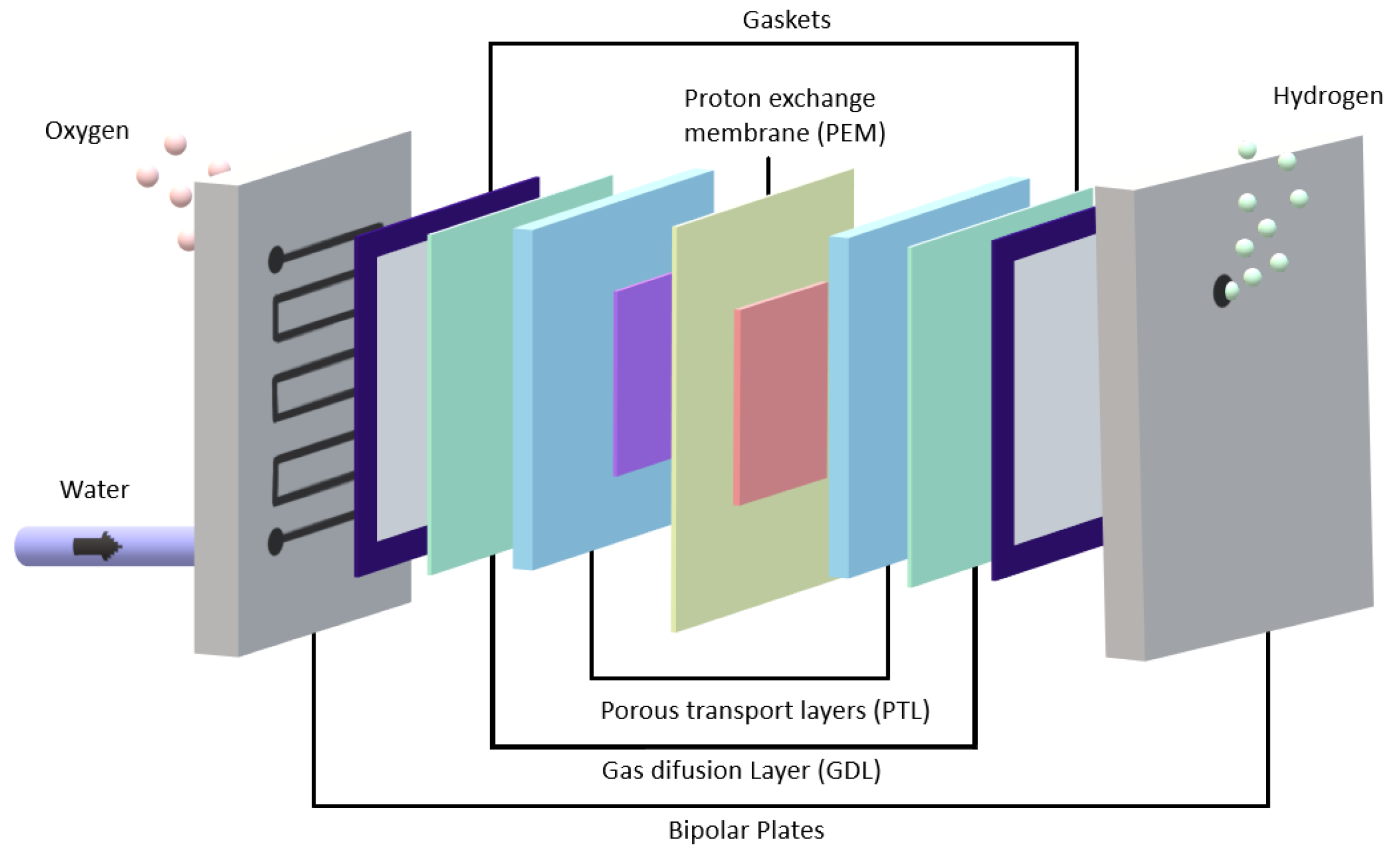

2.2. Structure of the Electrolyzer Cell Unit

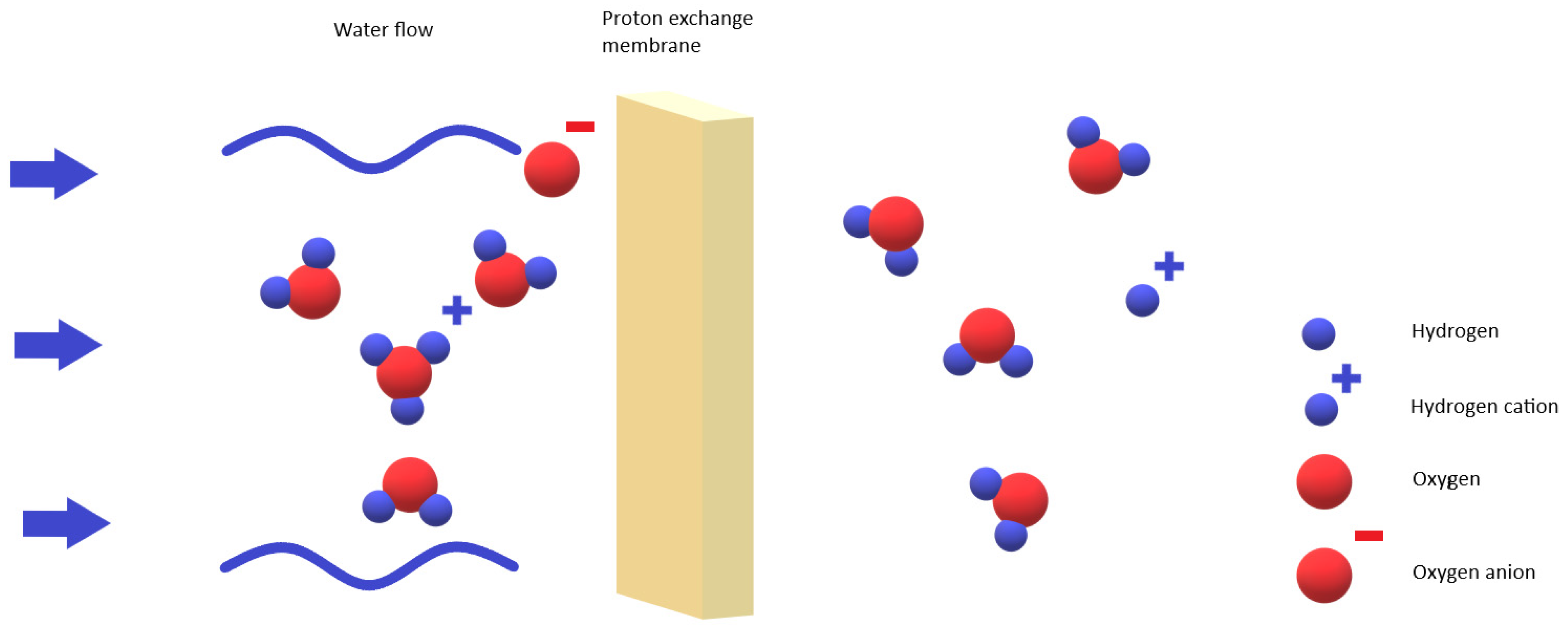

2.3. The Basic Working Mechanisms of PEMs and Electrolytes

3. Materials for PEMs

| Thermal Stability (°C) | Water Uptake (wt%) | Power Density (mW·m2) | Durability (h) | Proton Conductivity (mS/cm) | Hydrogen Permeability (Barrer) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common values | 70–100 [32] | 28–100 [33] | 800–2000 [34] | 40–50 [19] | 50–150 [35] | 0.1–1.0 [31] |

3.1. Commonly Used Materials

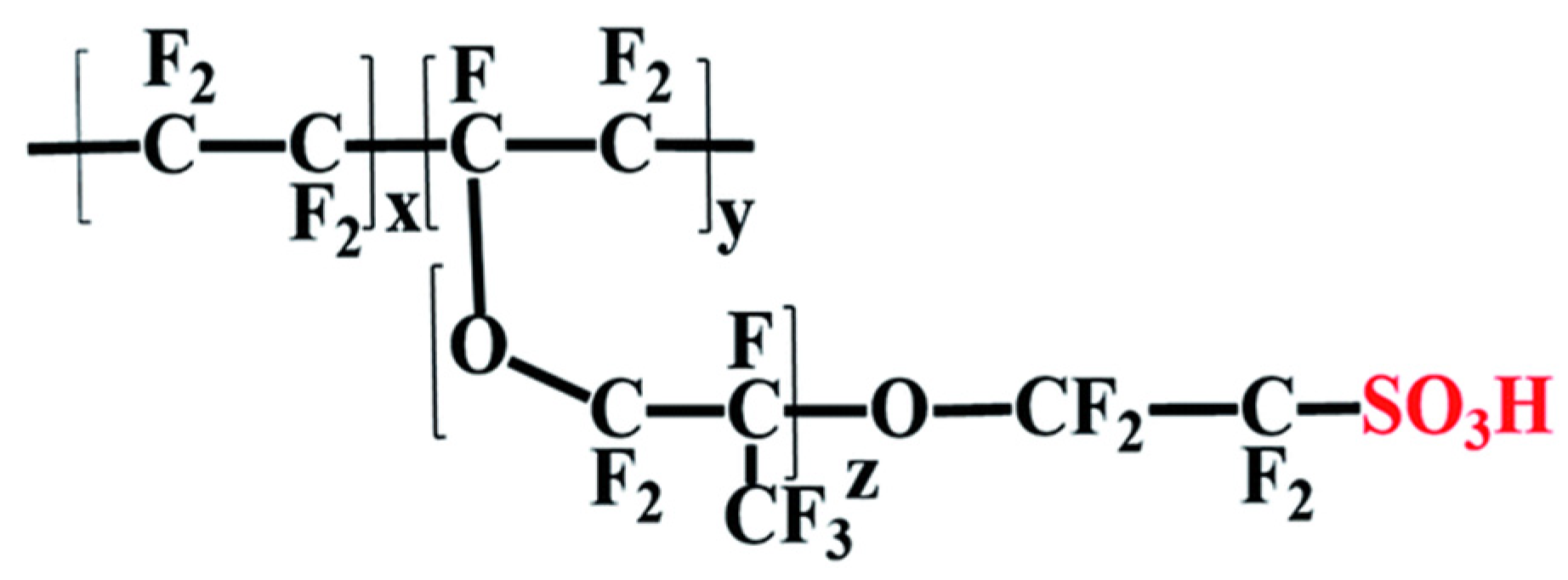

3.1.1. Nafions

- Nafion 112

- Nafion 115

- Nafion 117

- Nafion 212

- Disadvantages of Nafion

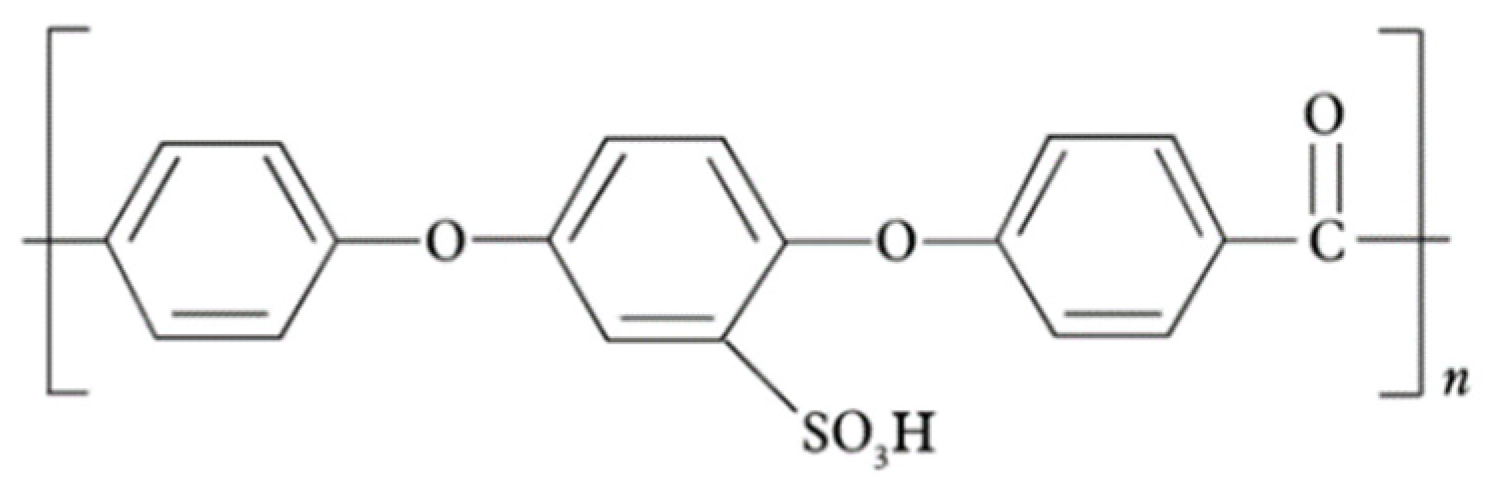

3.1.2. Poly(Ether Ether Ketone) (PEEK)

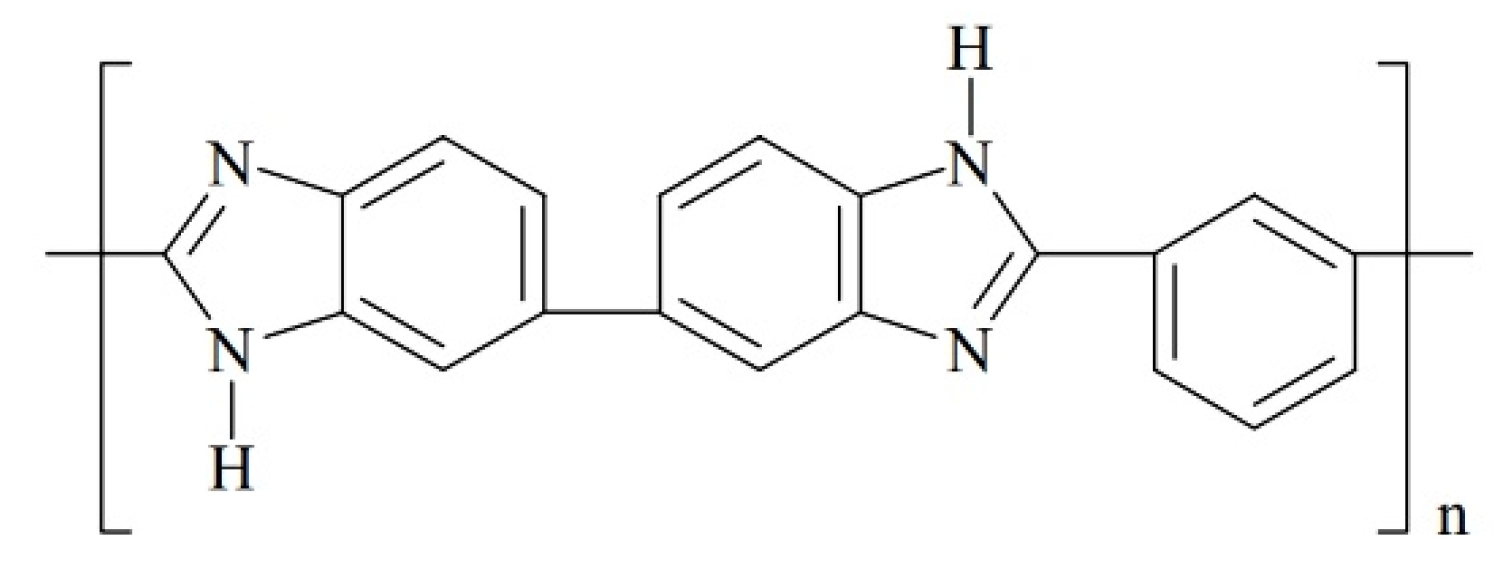

3.1.3. Polybenzimidazole (PBI)

3.1.4. Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) (sPAES)

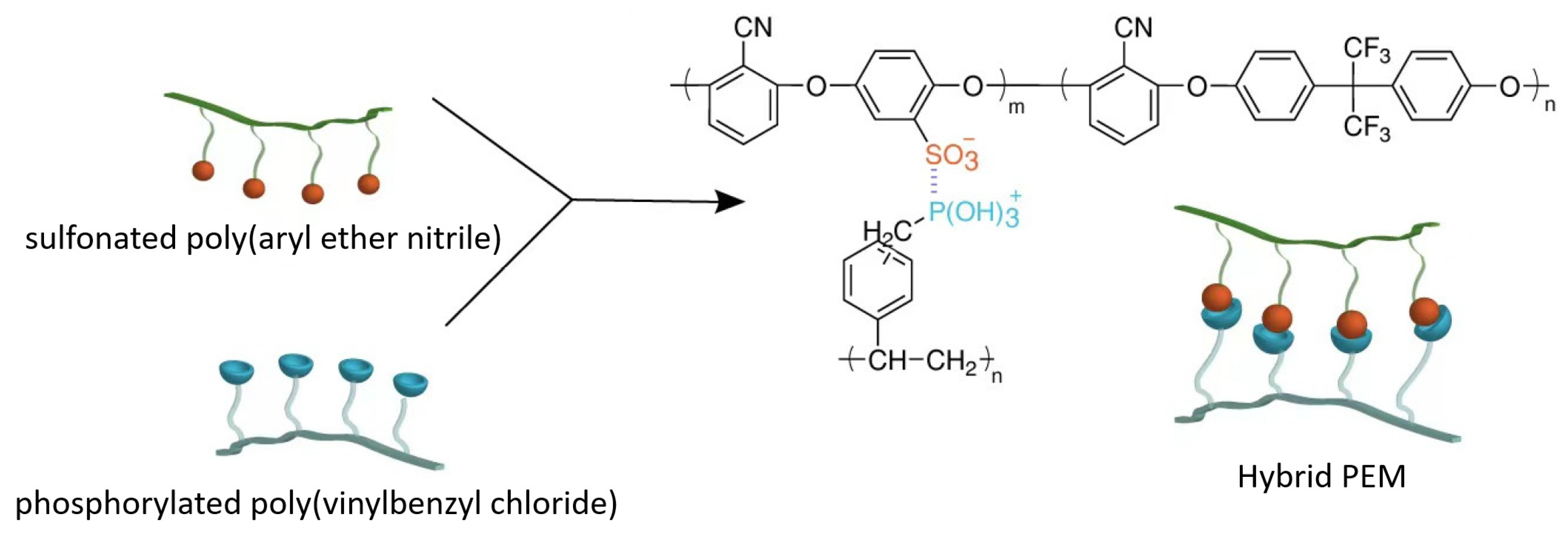

3.1.5. Hybrid Membranes

3.2. Sustainable Materials

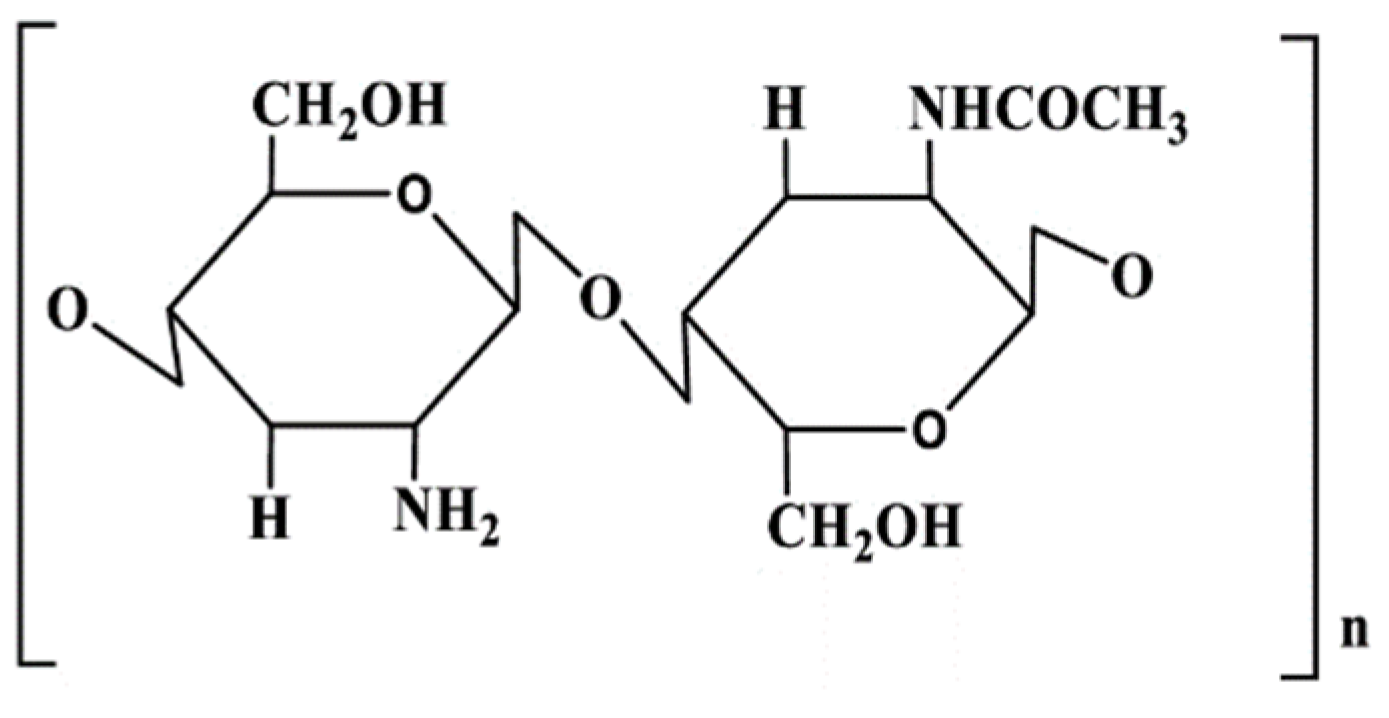

3.2.1. Chitosan

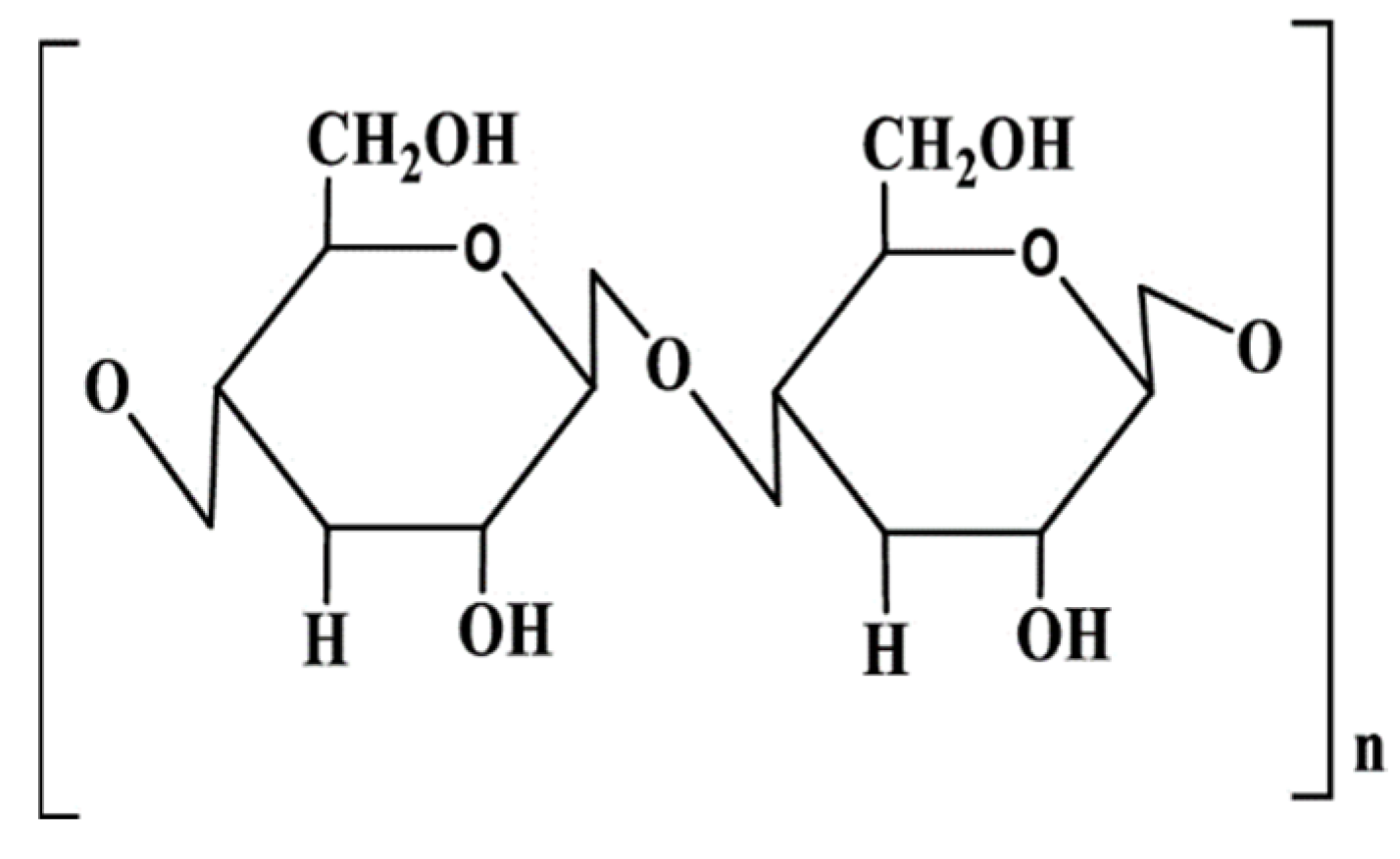

3.2.2. Cellulose

3.2.3. Sodium Alginate

3.2.4. Lignin

| Thermal Stability (°C) | Water Uptake (wt %) | Power Density (mW·m−2) | Durability (h) | Proton Conductivity (mS/cm) | Hydrogen Permeability (barrer) | Membrane Thickness (μm) | Emissions of CO2 (kg on 1 m2 membrane) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nafion 112 | 200 [49] | 28–30 [54] | 850 [48] | 2000 [55] | 100–120 [48] | 115 [152] | 50 [50] | 2.5 [84] |

| Nafion 115 | 180 [69] | 22–24 [54] | 800 [59] | 1000 [153] | 85–95 [59] | 110 [152] | 127 [154] | 2.5 [84] |

| Nafion 117 | 180 [49] | 30–32 [54] | 900 [15] | 2000 [61] | 100–120 [15] | 120 [152] | 183 [63] | 2.5 [84] |

| Nafion 212 | 180 [49] | 40–45 [54] | 860 [155] | 1000 [48] | 120–130 [155] | 115 [152] | 50 [154] | 2.5 [84] |

| PEEK | 300 [76] | 15–20 [77] | 400–500 [156] | 500 [139] | 60–70 [77] | 60 [157] | 50–100 [154] | 1.5–2 [84] |

| PBI | 400 [85] | 10–15 [148] | 600 [48] | 1500 [55] | 30–40 [77] | 5 [157] | 50–150 [154] | 1–1.5 [95] |

| sPAES | 260 [96] | 15–20 [107] | 500–700 [158] | 2000 [55] | 80–90 [107] | 25 [158] | 21–25 [107] | 1.2–2 [84] |

| Hybrid membrane Zirfon | 150–200 [114] | 22 [114] | 120–150 [59] | 800–1000 [114] | 50–80 [114] | 200–300 [114] | 175–300 [8] | 1.8–2.2 [114] |

| Chitosan | 200 [159] | 40–55 [136] | 100–200 [148] | 100–300 [148] | 15–25 [136] | 7 [157] | 112 [160] | 0.64 [128] |

| Cellulose | 200 [161] | 30–35 [134] | 200–300 [162] | 100–200 [136] | 20–30 [134] | 8–10 [134] | 46–62 [73] | 0.5–0.75 [73] |

| Sodium Alginate | 180–200 [163] | 35–45 [139] | 150–250 [148] | 50–100 [148] | 10–15 [139] | 6 [157] | 25–110 [164] | 1.2–1.5 [143] |

| Lignin | 160–190 [165] | 20–30 [148] | 50–100 [148] | 50–100 [148] | 5–15 [148] | 10–12 [148] | x | 0.5–1 [151] |

3.2.5. Summary

3.3. Composite Membranes

3.3.1. Inorganic Oxides

3.3.2. Carbon Based Nanomaterials

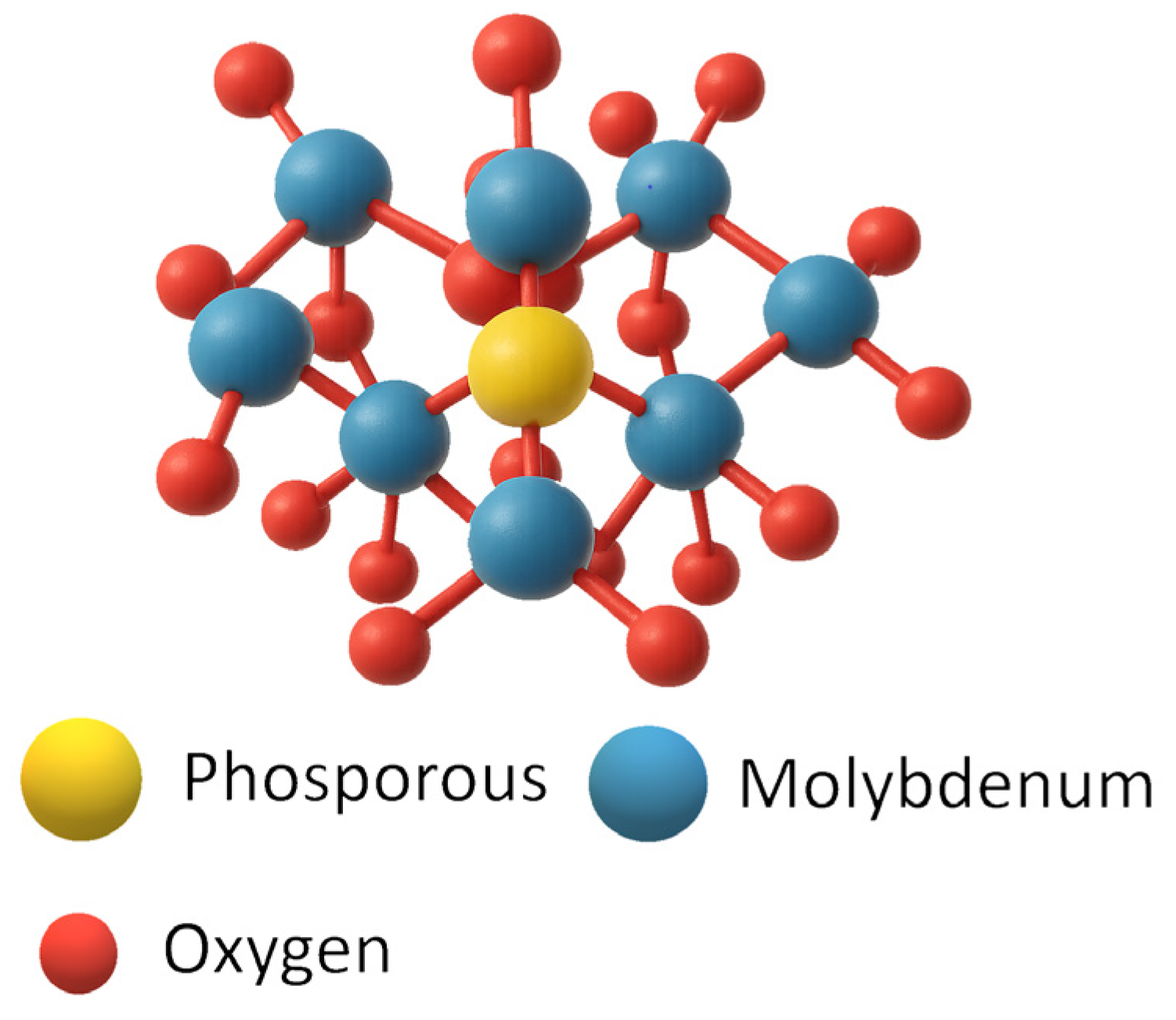

3.3.3. Heteropolyacids (HPAs)

3.3.4. Ionic Liquids

3.3.5. Recycling of PEMs

4. Methods of PEM Preparation

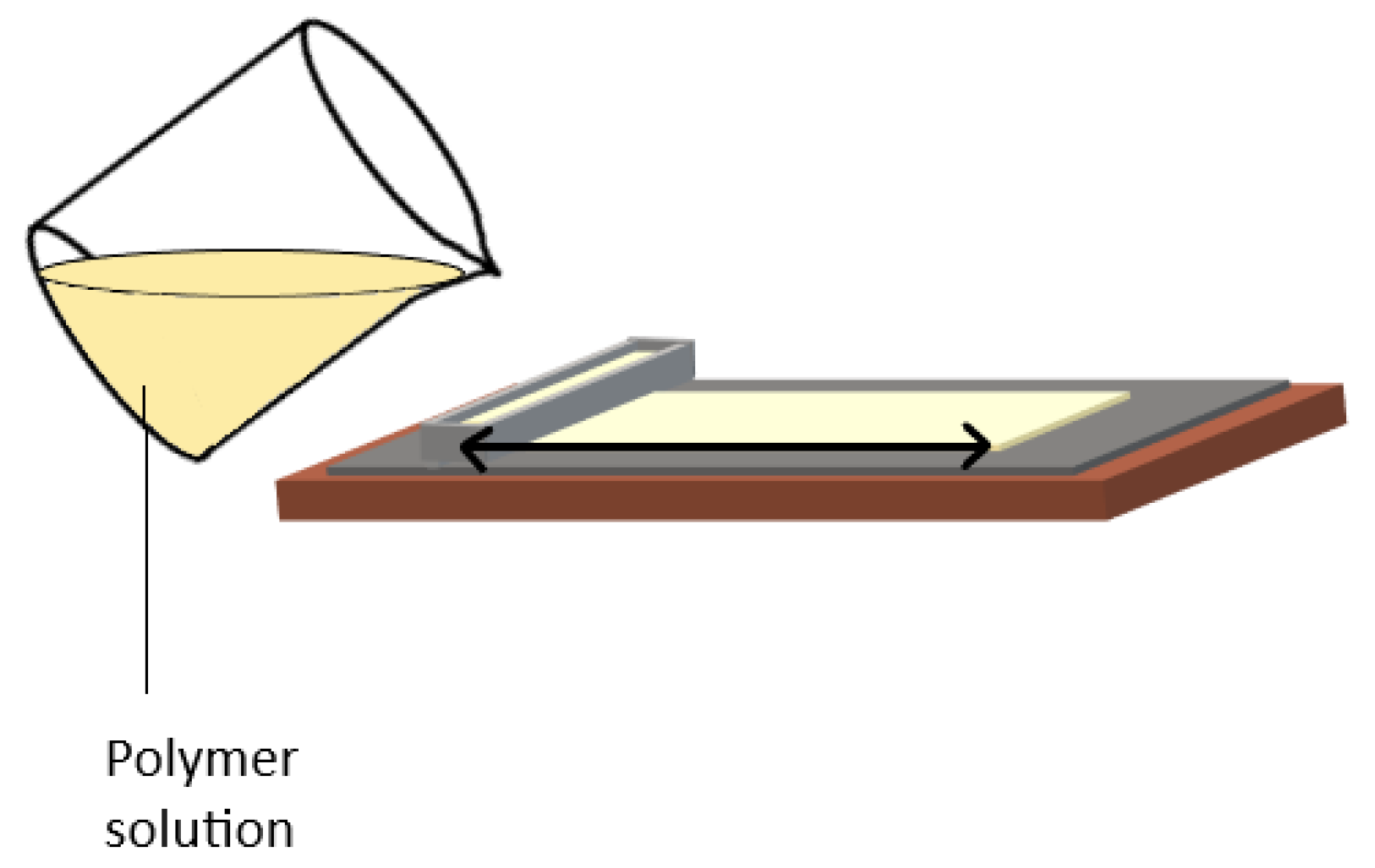

4.1. Casting

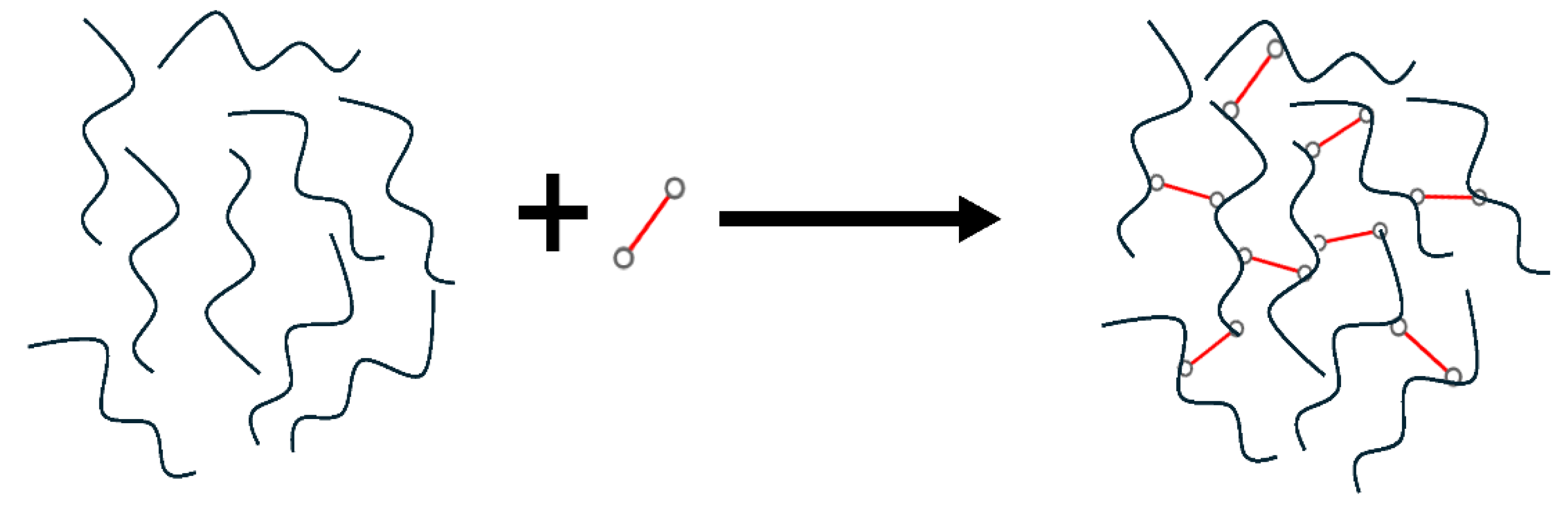

4.2. Cross-Linking

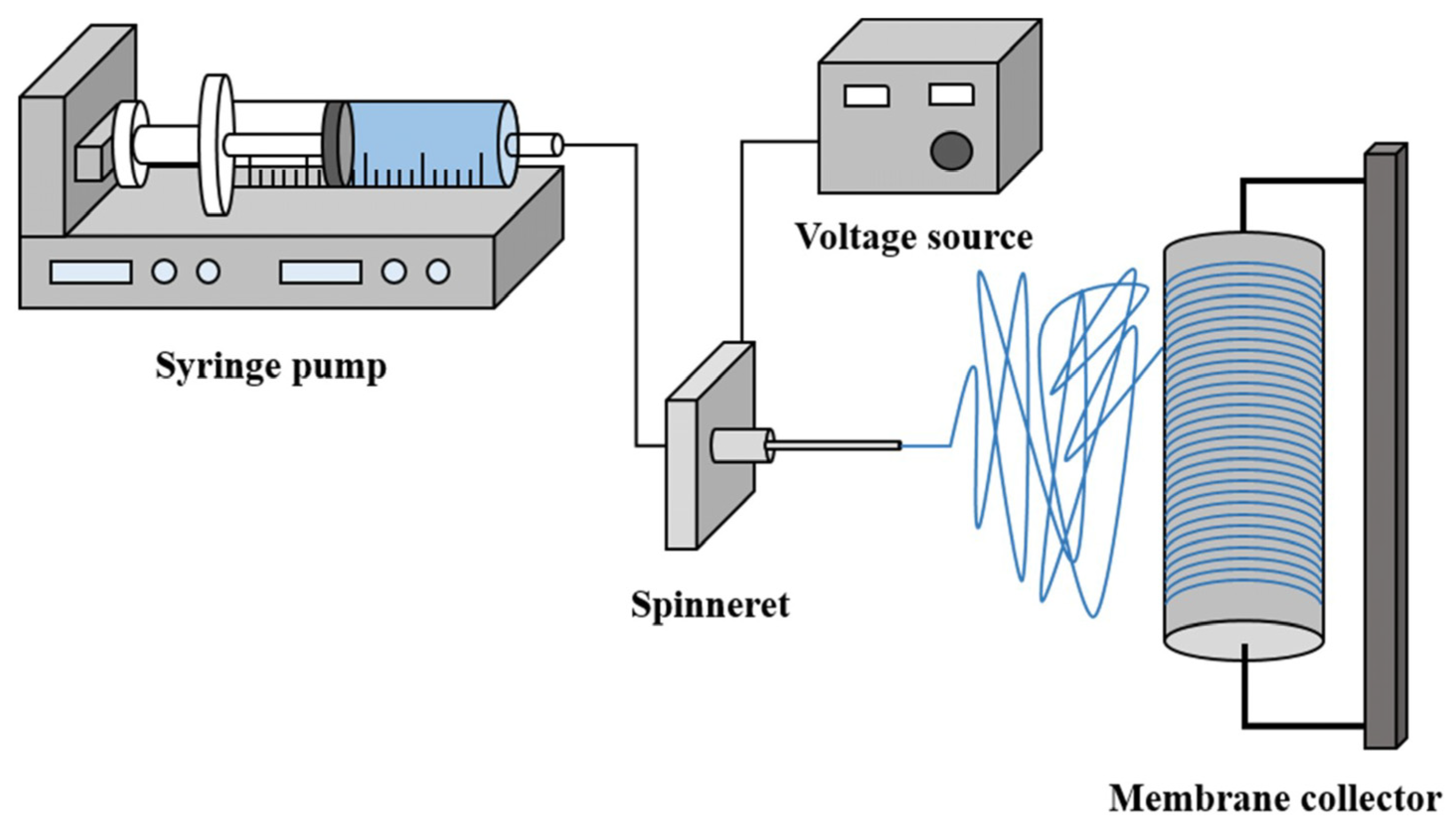

4.3. Electrospinning

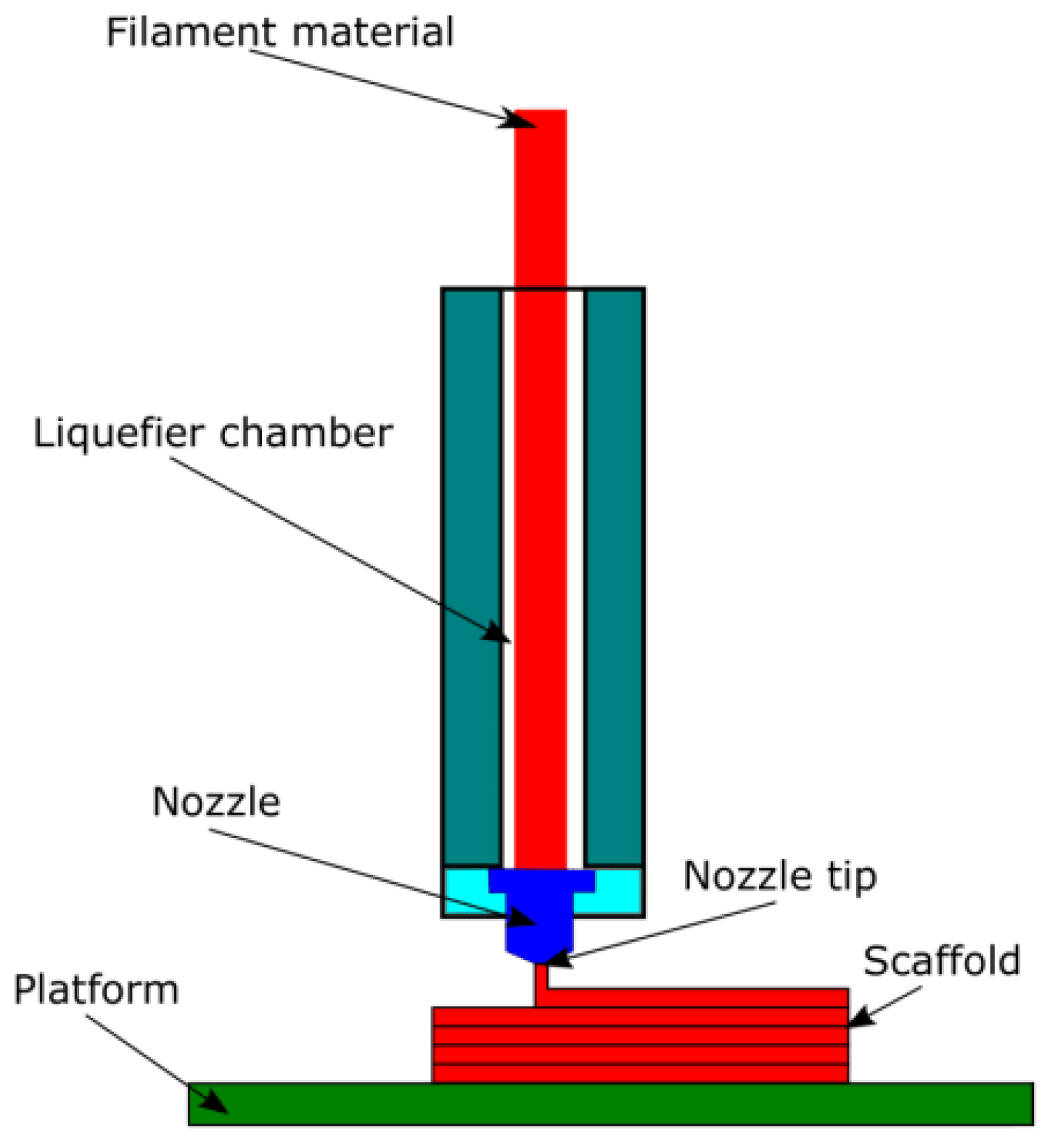

4.4. 3D-Printing

4.5. Polymer Composites Preparation

5. Challenges and Limitations of Sustainable PEMs

5.1. Performance Challenges

5.2. Scalability and Processability

5.3. Operating Conditions

5.4. Commercialization

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBN | Carbon-based nanomaterial |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| GDL | Gas diffusion layer |

| HER | Hydrogen evolution reaction |

| HPA | Heteropolyacid |

| IEC | Ion exchange capacity |

| IL | Ionic liquid |

| LCA | Life-cycle assessments |

| OER | Oxygen evolution reaction |

| PBI | Polybenzimidazole |

| PEEK | Polyether ether ketone |

| PEM | Proton exchange membrane |

| PEMFC | Proton exchange membrane fuel cell |

| PEMWE | Proton exchange membrane water electrolysis |

| PTFE | Polytetraflurethylene |

| PTL | Porous transport layer |

| PVA | Polyvinylacohol |

| PVDF | Polyvinyl difluoride |

| sPAES | Sulfonated poly(arylene ethersulfone) |

| TEA-TF | Triethylammonium triflate |

References

- Noyan, O.F.; Hasan, M.M.; Pala, N. A Global Review of the Hydrogen Energy Eco-System. Energies 2023, 16, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheekatamarla, P. Hydrogen and the Global Energy Transition—Path to Sustainability and Adoption across All Economic Sectors. Energies 2024, 17, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zheng, W.; Wei, Y.; Yan, Z. Current Status and Economic Analysis of Green Hydrogen Energy Industry Chain. Processes 2024, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Foglia, F.; Clancy, A.J.; Brett, D.J.L.; Miller, T.S. Nafion Matrix and Ionic Domain Tuning for High-Performance Composite Proton Exchange Membranes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechitailov, A.A.; Volovitch, P.; Glebova, N.V.; Krasnova, A. Features of the Degradation of the Proton-Conducting Polymer Nafion in Highly Porous Electrodes of PEM Fuel Cells. Membranes 2023, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segale, M.; Seadira, T.; Sigwadi, R.; Mokrani, T.; Summers, G. A New Frontier towards the Development of Efficient SPEEK Polymer Membranes for PEM Fuel Cell Applications: A Review. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 7979–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan-Huynh, T.N.; Pham, H.T.; Nguyen, P.T.; Tap, T.D.; Nguyen, T.H.; Phung, Q.; Tran, T.T.V.; Chang, Y.-J.; Lai, Y.-T.; Hoang, D. Cellulose-Based Proton Exchange Membrane Derived from an Agricultural Byproduct. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarico, D.; Fontananova, E.; Sibilllano, T.; Ciriminna, R.; Palermo, S.; Galiano, F.; Profio, G.D.; Figoli, A.; Petri, G.L.; Angellotti, G.; et al. CytroCell@Nafion: Enhanced Proton Exchange Membranes. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.W.; Jang, M.J.; Park, M.G.; Chen, Z.; Fowler, M. Effect of Components and Operating Conditions on the Performance of PEM Electrolyzers: A Review. Electrochem 2022, 3, 581–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodwong, B.; Guilbert, D.; Phattanasak, M.; Kaewmanee, W.; Hinaje, M.; Vitale, G. Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer Modeling for Power Electronics Control: A Short Review. C 2020, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, K.E.; Anderson, E.B.; Capuano, C.; Carter, B.; Dalton, L.; Hanlon, G.; Manco, J.; Niedzwiecki, M. Research Advances towards Low Cost, High Efficiency PEM Electrolysis. ECS Trans. 2010, 33, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, D.S.; Pinto, A.M.F.R. A Review on PEM Electrolyzer Modelling: Guidelines for Beginners. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 261, 121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. PEM Water Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production: Fundamentals, Advances, and Prospects. Carbon Neutrality 2022, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, A.E.; Çögenli, M.S.; Çelik, S.; Özcan, H. Experimental Investigation of Bio-Inspired Flow Field Design for AEM and PEM Water Electrolyzer Cells. Int. J. Energy Stud. 2023, 8, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Azam, A.M.I.; Li, N.K.; Zulkefli, N.N.; Masdar, M.S.; Majlan, E.H.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Mohd Zainoodin, A.; Mohamad Yunus, R.; Shamsul, N.S.; Husaini, T.; et al. Parametric Study and Electrocatalyst of Polymer Electrolyte Membrane (PEM) Electrolysis Performance. Polymers 2023, 15, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, K.; Garcia, M.; Michau, D.; Clisson, G.; Billinghurst, B.; Battaglia, J.-L.; Chevalier, S. Probing Membrane Hydration in Microfluidic Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Electrolyzers via Operando Synchrotron Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Lab Chip 2023, 23, 4002–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, J.; Xia, C.; Wang, P.; Xia, B.Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, X. Key Components and Design Strategy for a Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2200130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiber, S.; Sata, N.; Morawietz, T.; Ansar, S.A.; Jahnke, T.; Lee, J.K.; Bazylak, A.; Fallisch, A.; Gago, A.S.; Friedrich, K.A. A High-Performance, Durable and Low-Cost Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyser with Stainless Steel Components. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Qu, M.-R.; Qin, Y.-Y.; Zheng, X.-S.; Zhu, J.-F.; Li, H.; Su, X.-Z.; Yu, S.-H. Surface Reconstruction Activates Non-Noble Metal Cathode for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2405846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubras, F.; Damour, C.; Benne, M.; Boulevard, S.; Bessafi, M.; Grondin-Perez, B.; Kadjo, A.J.-J.; Deseure, J. A Non-Intrusive Signal-Based Fault Diagnosis Method for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer Using Empirical Mode Decomposition. Energies 2021, 14, 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, A.T.S.; Thiele, S. Closing the Hydrogen and Oxygen Mass Balance for PEM Water Electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 034506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tai, G.; Li, Y.; Sun, J. Highly Elastic, Healable, and Durable Anhydrous High-Temperature Proton Exchange Membranes Cross-Linked with Highly Dense Hydrogen Bonds. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, 2300007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, A.A.; Shaari, N.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Raduwan, N.F.; Yusoff, Y.N.; Khan, A.M.; Yousuf, S.; Ansari, M.N.M. Critical Review on Composite-Based Polymer Electrolyte Membranes toward Fuel Cell Applications: Progress and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18169–18193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijitha, R.; Nagaraja, K.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Rao, K.M.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Lakkaboyana, S.K.; Rao, K.S.V.K. Fabrication of Eco-Friendly Polyelectrolyte Membranes Based on Sulfonate Grafted Sodium Alginate for Drug Delivery, Toxic Metal Ion Removal and Fuel Cell Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lv, H.; Sun, Y.; Ji, W.; Shen, X.; Zhang, C. Constructing Supports–Network with N–TiO2 Nanofibres for Highly Efficient Hydrogen–Production of PEM Electrolyzer. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, I.; Zhu, Z.; Young-Gonzales, A.R.; Sacci, R.L.; Mamontov, E.; Gainaru, C.; Paddison, S.J.; Sokolov, A.P. Search for a Grotthuss Mechanism through the Observation of Proton Transfer. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Tang, H. Hydrophilic Channel Volume Behavior on Proton Transport Performance of Proton Exchange Membrane in Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justin Jose Sheela, A.S.; Moorthy, S.; Maria Mahimai, B.; Sekar, K.; Kannaiyan, D.; Deivanayagam, P. Sulfonated Poly Ether Sulfone Membrane Reinforced with Bismuth-Based Organic and Inorganic Additives for Fuel Cells. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 27510–27518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsabadi, A.; Tohidian, M.; Hemmasi, E.; Makki, H. Proton Exchange Membranes Based on Sulfonated Polybutylene Fumarate: Preparation and Characterization. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 3320–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.B.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, T.; Jeon, S.-Y.; Kim, J.; Yoo, Y.-S. Operational Characteristics of High-Performance kW Class Alkaline Electrolyzer Stack for Green Hydrogen Production. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol 2021, 12, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaciari, J.C.; Gerhardt, M.R.; Zhou, J.; Regmi, Y.N.; Danilovic, N.; Bell, A.T.; Weber, A.Z. The Role of Water in Vapor-Fed Proton-Exchange-Membrane Electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 104508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Bazylak, A. Optimizing Porous Transport Layer Design Parameters via Stochastic Pore Network Modelling: Reactant Transport and Interfacial Contact Considerations. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 013541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, Z. Impact of Water Properties on the Performance of PEM Electrolyzer. Preprints 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fakourian, S.; Alizadeh, M. Hydrogen Generation from the Wastewater of Power Plants via an Integrated Photovoltaic and Electrolyzer System: A Pilot-Scale Study. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 6099–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Yao, D.; Chi, J.; Sun, S.; Shao, Z. Low-Loading and Highly Stable Membrane Electrode Based on an Ir@WOxNR Ordered Array for PEM Water Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 15073–15082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Dong, Y.; Zhong, S.; Chen, D.; Zeng, G.; He, W. Optimizing the Molecular Weight of Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride) for Competitive Perfluorosulfonic Acid Membranes. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) Rapid Res. Lett. 2022, 16, 2100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Pant, R.; Venkatnathan, A.; Lyulin, A.V. Molecular-Dynamics Modeling of Nafion Membranes. Macromol. Symp. 2022, 405, 2100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goo, B.-H.; Al Munsur, A.Z.; Choi, O.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, O.J.; Kim, T.-H. Sulfonated Poly(Ether Sulfone)-Coated and -Blended Nafion Membranes with Enhanced Conductivity and Reduced Hydrogen Permeability. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 11418–11433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayadevi, T.S.; Goo, B.-H.; Paek, S.Y.; Choi, O.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, O.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, T.-H. Nafion Composite Membranes Impregnated with Polydopamine and Poly(Sulfonated Dopamine) for High-Performance Proton Exchange Membranes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 12956–12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.P.; Tinh, V.D.C.; Kim, D. Improved Oxidative Stability by Embedded Cerium into Graphene Oxide Nanosheets for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Application. Membranes 2021, 11, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacub, N.S.; Rauf, L.N.; Suryanto, S.; Bhuana, C. Pengaruh Temperatur Air Terhadap Produksi Hidrogen (H2) Metode Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Electrolyzer. J. Tek. Mesin Sinergi 2025, 23, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, D.V.; Cohen, L.; Jin, J.; Dondapati, J.; Lin, Z.; Weimer, M.S.; Harris, S.; Dameron, A.A.; Junker, S.; Hawkes, J.; et al. Nanoscale Proton-Conducting Oxide Membranes for Low Temperature Water Electrolysis. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frensch, S.H.; Fouda-Onana, F.; Serre, G.; Thoby, D.; Araya, S.S.; Kær, S.K. Influence of the Operation Mode on PEM Water Electrolysis Degradation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 29889–29898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lufrano, E.; Simari, C.; Di Vona, M.L.; Nicotera, I.; Narducci, R. How the Morphology of Nafion-Based Membranes Affects Proton Transport. Polymers 2021, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monopoli, A.; Casiello, M.; Cotugno, P.; Milella, A.; Palumbo, F.; Fracassi, F.; Nacci, A. Synthesis of Tailored Perfluoro Unsaturated Monomers for Potential Applications in Proton Exchange Membrane Preparation. Molecules 2021, 26, 5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yamamoto, K.; Hirai, T.; Uchiyama, T.; Ohta, N.; Takao, N.; Matsumoto, M.; Imai, H.; Sugawara, S.; Shinohara, K.; et al. Morphology Changes in Perfluorosulfonated Ionomer from Thickness and Thermal Treatment Conditions. Langmuir 2020, 36, 3871–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavorotnaya, U.M.; Privalov, A.F.; Kresse, B.; Vogel, M.; Ponomarev, I.I.; Volkova, Y.A.; Sinitsyn, V.V. Diffusion in Sulfonated Co-Polynaphthoyleneimide Proton Exchange Membranes with Different Ratios of Hydrophylic to Hydrophobic Groups Studied Using SFG NMR. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 8823–8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Al Munsur, A.Z.; Paek, S.Y.; Jeon, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, T.-H. Development of High-Performance Polymer Electrolyte Membranes through the Application of Quantum Dot Coatings to Nafion Membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 15616–15624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, A.O.; Glebova, N.V.; Kastsova, A.G.; Rabchinskii, M.K.; Nechitailov, A.A. Thermal Stabilization of Nafion with Nanocarbon Materials. Polymers 2023, 15, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K.; Yoshida, M.; Kondo, Y. Performance Characteristics of a Free-Breathing Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell with Various Channel Shapes. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jheng, L.-C.; Cheng, C.-W.; Ho, K.-S.; Hsu, S.L.-C.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Lin, B.-Y.; Ho, T.-H. Dimethylimidazolium-Functionalized Polybenzimidazole and Its Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Membranes for Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Polymers 2021, 13, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, G.G.; Ibrahim, A.; Borello, D.; El-Kharouf, A. Composite Polymers Development and Application for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Technologies—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, P.; Sui, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhou, Q. The Advances Development of Proton Exchange Membrane with High Proton Conductivity and Balanced Stability in Fuel Cells. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronova, E.Y.; Voropaeva, D.Y.; Lysova, A.A.; Korchagin, O.V.; Bogdanovskaya, V.A.; Yaroslavtsev, A.B. On the Properties of Nafion Membranes Recast from Dispersion in N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone. Polymers 2022, 14, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.S.; Jang, S.; Choi, E.; Jo, S.; Kim, S.M.; Yoo, S.J. Sandwich-like Nafion Composite Membrane with Ultrathin Ceria Barriers for Durable Fuel Cells. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 46, 6457–6470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kujawski, W.; Rynkowska, E. Advancements in Proton Exchange Membranes for High-Performance High-Temperature Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (HT-PEMFC). Rev. Chem. Eng. 2022, 38, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Munsur, A.Z.; Goo, B.-H.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, O.J.; Paek, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, T.-H. Nafion-Based Proton-Exchange Membranes Built on Cross-Linked Semi-Interpenetrating Polymer Networks between Poly(Acrylic Acid) and Poly(Vinyl Alcohol). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 28188–28200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, S.; Vagin, M.; Gueskine, V.; Erlandsson, J.; Boissard, Y.; Korhonen, L.; Berggren, M.; Wågberg, L.; Crispin, X. Sulfonated Cellulose Membranes Improve the Stability of Aqueous Organic Redox Flow Batteries. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2022, 3, 2200016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-D. High-Temperature Water Electrolysis Properties of Membrane Electrode Assemblies with Nafion and Crosslinked Sulfonated Polyphenylsulfone Membranes by Using a Decal Method. Membranes 2024, 14, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Z.; Liu, X.; Xia, W.; Ma, M.; Cao, D. Construction and Prospect of Noble Metal-Based Catalysts for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers. Small Struct. 2023, 4, 2300081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Pang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wu, L.; Hu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, C. Synergistic Utilization of a CeO2-Anchored Bifunctionalized Metal–Organic Framework in a Polymer Nanocomposite toward Achieving High Power Density and Durability of PEMFC. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 5270–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.G.; Ferreira, R.; Falcão, D.; Pinto, A.M.F.R. Experimental Study on the Catalyst-Coated Membrane of a Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer. Energies 2022, 15, 7937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernihough, O.; Ismail, M.S.; El-kharouf, A. Intermediate Temperature PEFC’s with Nafion® 211 Membrane Electrolytes: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Membranes 2022, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, G.; Xu, C. Sulfonated Poly (Fluorenyl Ether Ketone Nitrile) Membranes Used for High Temperature PEM Fuel Cell. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, F.; Stähler, A.; Stähler, M.; Müller, M.; Lehnert, W.; Carmo, M. High-Pressure Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Water Electrolyzers: Is It Worth It? Meet. Abstr. 2020, MA2020-01, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hu, B.; Du, J.; Cheng, D.; Zang, H.-Y.; Ge, X.; Tan, H.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Jin, Z.; et al. Precise Molecular-Level Modification of Nafion with Bismuth Oxide Clusters for High-Performance Proton-Exchange Membranes. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 6141–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Schröter, J.; Möckl, M.; Gasteiger, H.A. Analysis of Gas Permeation Phenomena in a PEM Water Electrolyzer Operated at High Pressure and High Current Density. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 124502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Trinke, P.; Bensmann, B.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. Hydrogen Crossover in PEM Water Electrolysis at Current Densities up to 10 A cm−2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 094507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Trieu, D.; Zheng, D.; Ji, W.; Qu, H.; Ding, T.; Qiu, D.; Qu, D. Nafion/PTFE Composite Membranes for a High Temperature PEM Fuel Cell Application. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 11086–11094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanathan, S.; Mohamed, H.; Jaafar, J.; Ilbeygi, H. Composite Proton Electrolyte Membranes C Poly Ether-Ether Ketone (SPEEK) at Various Amount of Mesoporous Phosphotungstic Acid (mPTA) for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Application. J. Appl. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2020, 24, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.C.; Jeon, I.; Jeong, E.S.; Jho, J.Y. Mechanical Properties and Chemical Durability of Nafion/Sulfonated Graphene Oxide/Cerium Oxide Composite Membranes for Fuel-Cell Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A.; Liu, F.; Kulik, H.J. Uncovering Alternate Pathways to Nafion Membrane Degradation in Fuel Cells with First-Principles Modeling. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 15094–15106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, J. Cellulose Proton Conductor: Both Sulfonic Acid and Hydrophobic Group Functionalization Enable High Proton Conductivity. JACS Au 2025, 5, 4165–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, H.; Zhai, L.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Li, T.; He, S.; Chai, S.; Usenko, A.; Li, H. Nafion Hybrid Membranes with Enhanced Ion Selectivity via Supramolecular Complexation for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, A.; Sakata, W.; Ishida, E.; Mitsuru, T.; Sato, Y. Application of High-Performance Hydrocarbon-Type Sulfonated Polyethersulfone for Vanadium Redox-Flow Battery. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 19405–19412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Tsui, J.H.; Xu, F.; Lee, S.H.; Sung, S.-K.; Lee, H.J.; Wang, C.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.-H. Fabrication of Micro- and Nanopatterned Nafion Thin Films with Tunable Mechanical and Electrical Properties Using Thermal Evaporation-Induced Capillary Force Lithography. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8, 2002005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, K.; Chen, J.; Sawada, S.; Radulescu, A.; Zhao, Y.; Maekawa, Y. Structural Factors for the Chemical Stability of Graft-Type Polymer Electrolyte Membranes Evaluated from the Local Hydration Number. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 13585–13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, F.; Guilbert, D.; El-Ganaoui, M. Investigation of Electrical and Thermal Performance of a Commercial PEM Elec-trolyzer under Dynamic Solicitations. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, R.J.; Young, J.L.; Schuler, T.; Bender, G.; Roberts, G.M.; Ayers, K.E. Measurement of Resistance, Porosity, and Water Contact Angle of Porous Transport Layers for Low-Temperature Electrolysis Technologies. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 911077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Jia, D. Research on the Influence of Ripple Voltage on the Performance of a Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer. Energies 2023, 16, 6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jery, A.; Salman, H.M.; Al-Khafaji, R.M.; Nassar, M.F.; Sillanpää, M. Thermodynamics Investigation and Artificial Neural Network Prediction of Energy, Exergy, and Hydrogen Production from a Solar Thermochemical Plant Using a Polymer Membrane Electrolyzer. Molecules 2023, 28, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, M.; Smith, K.; Dodwell, J.; Hinds, G.; Shearing, P.R.; Brett, D.J.L. Mass Transport in PEM Water Electrolysers: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Ma, H.; Khan, M.; Hsiao, B.S. Recent Advances and Challenges in Anion Exchange Membranes Development/Application for Water Electrolysis: A Review. Membranes 2024, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babatunde, O.M.; Akintayo, B.D.; Emezirinwune, M.U.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Environmental Impact Assessment of a 1 kW Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell: A Mid-Point and End-Point Analysis. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 352–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, A.H.; Messana, D.A.; Santoro, S.; Tufa, R.A.; Curcio, E.; Di Profio, G.; Fontananova, E. Energy Harvesting from Brines by Reverse Electrodialysis Using Nafion Membranes. Membranes 2020, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likit-anurak, K.; Teel, H.; Shimpalee, S.; Meekins, B. Experimentally-Validated CFD Model of an Anhydrous HCl Electrolyzer. Meet. Abstr. 2024, MA2024-02, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likit-anurak, K.; Karki, I.; Howard, B.I.; Murdock, L.; Mukhin, N.; Brannon, J.; Hepstall, A.; Young, B.; Shimpalee, S.; Benicewicz, B.; et al. Polybenzimidazole Membranes as Nafion Replacement in Aqueous HCl Electrolyzers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 5429–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Ma, M.; Zhao, B.; Liang, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, M.; Gao, C.; Huang, F.; et al. Highly Efficient and Durable Water Electrolysis at High KOH Concentration Enabled by Cationic Group-Free Ion Solvating Membranes in Free-Standing Gel Form. Small 2025, 21, 2408159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likit-anurak, K.; Mukhin, N.Y.; Brannon, J.K.; Hepstall, A.M.; Murdock, L.; Benicewicz, B.; Shimpalee, S.; Meekins, B. Para-Polybenzimidazole Membranes for HCl Electrolysis at High (T <160 °C) Temperatures. Meet. Abstr. 2022, MA2022-02, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zholobko, O.; Wu, X.-F.; Aulich, T.; Thakare, J.; Hurley, J. Polybenzimidazole-Based Polymer Electrolyte Membranes for High-Temperature Fuel Cells: Current Status and Prospects. Energies 2021, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, P.; Li, Z.; Guo, H.; Pei, H.; Yin, X. Construction of Novel Proton Transport Channels by Triphosphonic Acid Proton Conductor-Doped Crosslinked mPBI-Based High-Temperature and Low-Humidity Proton Exchange Membranes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 2861–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Palafox Gonzalez, P.; Thangadurai, V. A Critical Review of Electrolytes for Advanced Low- and High-Temperature Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 29674–29699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, K.; Wang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Wu, Q.; Bai, X.; Hamdy, M.S.; Chen, H.; et al. Status and Perspectives of Key Materials for PEM Electrolyzer. Nano Res. Energy 2022, 1, e9120032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Yang, S.; Kang, B.-H.; Park, J.; Park, G.; Baek, J.; Oh, H.-M.; So, Y.; Park, S.-H.; Jeong, Y.; et al. Improved Performance of High-Temperature Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells by Purified CNT Nanoporous Sheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Abad, S.; Fernández-Mancebo, S.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Lobato, J. Characterization of PBI/Graphene Oxide Composite Membranes for the SO2 Depolarized Electrolysis at High Temperature. Membranes 2022, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Zeng, Y.; Song, J.; Meng, Z. Insights Into the Thermal Stability and Proton Transport Mechanism of PTFE-Nafion Composite Membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, T.; Aboki, J.; Guo, R. Disulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) Random Copolymers Containing Hierarchical Iptycene Units for Proton Exchange Membranes. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Tan, Y.; Lu, C.; Mao, S.; Kang, L.; Liao, H. Novel Trisulfonated Poly(Phthalazinone Ether Phosphine Oxide)s with High Dimensional Stability for Proton Exchange Membrane. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 4999–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasekaran, P.; Mahimai, B.M.; Deivanayagam, P. Novel Cross-Linked Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)-Based Electrolyte Membranes for Fuel Cell Applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 26521–26527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxey, D.; Devendhar Singh, S.K.; Plunkett, E.; Moore, R.B.; Arnett, N.Y. Fabrication of Thermally Stable Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) Containing Sulfonic Acid Based Additives for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202203309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Lotebulo Ndruru, S.T.C.; Bundjali, B.; Wahyuningrum, D.; Arcana, I.M. Synthesis of Polymer Electrolyte Membranes from Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Ketones) with Partial Substitution of Carboxylate Acid Group. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202202583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ko, H.; Nam, S.Y.; Kim, K. Study on Control of Polymeric Architecture of Sulfonated Hydrocarbon-Based Polymers for High-Performance Polymer Electrolyte Membranes in Fuel Cell Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, R.; Mandal, A.K.; Banerjee, S. Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) Functionalized Polysilsesquioxane Hybrid Membranes with Enhanced Proton Conductivity. e-Polymers 2020, 20, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Rivera, G.; Suleiman, D. Random Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) and Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Ketone) Membranes for Fuel Cell Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhu, J.; Lin, M.; Xu, J.; Xie, Z.; Chen, D. Tetra-Alkylsulfonate Functionalized Poly(Aryl Ether) Membranes with Nanosized Hydrophilic Channels for Efficient Proton Conduction. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 40, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hickner, M.; Kim, Y.S.; Zawodzinski, T.A.; McGrath, J.E. Direct Polymerization of Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) Random (Statistical) Copolymers: Candidates for New Proton Exchange Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 197, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, K.; Han, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Sung, Y.-E.; Lee, J.-C. End-Group Cross-Linked Membranes Based on Highly Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) with Vinyl Functionalized Graphene Oxide as a Cross-Linker and a Filler for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Application. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 3456–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Chen, N.; Zheng, Z.; Xiong, L.; Chen, D. Preparation of Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether)/SiO2 Composite Membranes with Enhanced Proton Selectivity for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. Molecules 2023, 28, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Samuel, A.; Faqeeh, A.H.; Li, W.; Ertekin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gadegaard, N.; Moran, D.A.J.; Symes, M.D.; Ganin, A.Y. Assessing Challenges of 2D-Molybdenum Ditelluride for Efficient Hydrogen Generation in a Full-Scale Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Water Electrolyzer. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zou, J.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Cai, W. Bi-Functional Composting the Sulfonic Acid Based Proton Exchange Membrane for High Temperature Fuel Cell Application. Polymers 2020, 12, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Zhao, P.; Meng, L.; Li, N.; Chen, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, J. Study on the Application Performance of Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Functionalized with Triethyl Phosphite-Modified Graphene Oxide in Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 34156–34166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, T.; Kajita, T.; Nishimoto, M.; Tanaka, H.; Sato, K.; Marium, M.; Mufundirwa, A.; Iwamoto, H.; Noro, A. Polymer Electrolyte Membranes of Polystyrene with Directly Bonded Alkylenephosphonate Groups on the Side Chains. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 15150–15161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhuang, Y. Structural Architectures of Polymer Proton Exchange Membranes Suitable for High-Temperature Fuel Cell Applications. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Lee, H.I.; Bernäcker, C.I.; Weißgärber, T.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.-K.; Cho, W.-C. Zirconia Toughened Alumina-Based Separator Membrane for Advanced Alkaline Water Electrolyzer. Polymers 2022, 14, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Dong, T.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Jia, W.; Meng, Z.; Zhou, M.; Tang, H. Phosphonate Poly(Vinylbenzyl Chloride)-Modified Sulfonated Poly(Aryl Ether Nitrile) for Blend Proton Exchange Membranes: Enhanced Mechanical and Electrochemical Properties. Polymers 2023, 15, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Oberoi, A.S.; Singh, T. Factors Influencing the Performance of PEM Fuel Cells: A Review on Performance Parameters, Water Management, and Cooling Techniques. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 3810–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutagulla, S.; Le, N.H.; Caldino Bohn, I.T.; Stacy, B.J.; Favela, C.S.; Slack, J.J.; Baker, A.M.; Kim, H.; Shin, H.S.; Korgel, B.A.; et al. Comparative Studies of Atomically Thin Proton Conductive Films to Reduce Crossover in Hydrogen Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 59358–59369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakiya, T.; Tanaka, M.; Kawakami, H. Fabrication and Electrolyte Characterizations of Nanofiber Framework-Based Polymer Composite Membranes with Continuous Proton Conductive Pathways. Membranes 2021, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Arges, C.G.; Xu, H.; Kim, Y.S. Membrane Strategies for Water Electrolysis. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 3447–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.S.; Soni, U.; Chauhan, S.S.; Verma, P.; Choudhary, V. Development of Functionalized Quantum Dot Modified Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Membranes for Fuel Cell Applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 47536–47544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surti, P.V.; Kailasa, S.K.; Mungray, A.K. Development of a Novel Composite Polymer Electrolyte Membrane for Application as a Separator in a Dual Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 5182–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.T.T.; Le, T.Q.; Duc Cuong, N.; Linh, N.L.M.; Le, L.S.; Tran, T.D.; Nguyen, H.P. Polythiophene-Wrapped Chitosan Nanofibrils with a Bouligand Structure toward Electrochemical Macroscopic Membranes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13680–13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaja, L.; Rachmawati, D.R.; Hartanti, E.A. Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan/κ-Carrageenan/Mesoporous Phosphotungstic Acid (mPTA) Electrolyte Membranes for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell (DMFC) Applications. Defect Diffus. Forum 2022, 416, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirrouz, M.; Melino, F.; Ancona, M.A. Fault Detection and Diagnosis Methods for Green Hydrogen Production: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 27747–27774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, E.-R.; Pandele, A.M.; Tuncel, C.; Miculescu, F.; Voicu, S.I. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan/LDH Composite Membranes for Drug Delivery Application. Membranes 2023, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunachalam, M.; Sinopoli, A.; Aidoudi, F.; Creager, S.E.; Smith, R.; Merzougui, B.; Aïssa, B. High Performance of Anion Exchange Blend Membranes Based on Novel Phosphonium Cation Polymers for All-Vanadium Redox Flow Battery Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 45935–45943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meramo, S.; González-Delgado, Á.D.; Sukumara, S.; Fajardo, W.S.; León-Pulido, J. Sustainable Design Approach for Modeling Bioprocesses from Laboratory toward Commercialization: Optimizing Chitosan Production. Polymers 2022, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, R.; Dong, C.-L.; Huang, Y.-C.; Ma, M.; Shi, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, M.; et al. Alloyed Pt Single-Atom Catalysts for Durable PEM Water Electrolyzer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2214795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Steen, S.M.; Mo, J.; Zhang, F.-Y. Electrochemical Performance Modeling of a Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer Cell for Hydrogen Energy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 7006–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Gu, X.; Cui, X.; Tang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Cho, J. Strategies for the Design of Ruthenium-Based Electrocatalysts toward Acidic Oxygen Evolution Reaction. EES Catal. 2023, 1, 619–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z.; Kamarudin, S.K. A Review of Alkaline Solid Polymer Membrane in the Application of AEM Electrolyzer: Materials and Characterization. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 18337–18354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontananova, E.; Ciriminna, R.; Talarico, D.; Galiano, F.; Figoli, A.; Profio, G.D.; Mancuso, R.; Gabriele, B.; Pomelli, C.S.; Guazzelli, L.; et al. CytroCell@PIL: A New Citrus Nanocellulose-Polymeric Ionic Liquid Composite for Enhanced Anion Exchange Membranes. Nano Sel. 2025, 6, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, H.; Jeong, Y.-G.; Choi, C.; Hwang, I.; Song, S.; Nam, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, K. Polymer Electrolyte Membranes Containing Functionalized Organic/Inorganic Composite for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, G.; Oh, T.H.; Thangarasu, S. Modified Cellulose Proton-Exchange Membranes for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Polymers 2023, 15, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Ye, J.; Qin, Z.; Sun, L. Polytetrafluoroethylene Modified Nafion Membranes by Magnetron Sputtering for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. Coatings 2022, 12, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, D.; Balaguru, S.; Swaminathan, E.; Gangasalam, A. Composite Proton Exchange Membrane of Cellulose Triacetate Polymer Integrated with Polyacrylic Acid and Triazole Based Copolymer for Balanced Proton Conduction and Methanol Permeability. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaari, N.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Basri, S.; Shyuan, L.K.; Masdar, M.S.; Nordin, D. Enhanced Proton Conductivity and Methanol Permeability Reduction via Sodium Alginate Electrolyte-Sulfonated Graphene Oxide Bio-Membrane. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.K.; Chatterjee, D.P. Hybrid Polymer Gels for Energy Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 12593–12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Lou, Z.X.; Ding, Y.; Li, X.; Mao, F.; Yuan, H.Y.; Liu, P.F.; Yang, H.G. Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysts for the Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer: Challenges on Stability. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2201130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Xia, Z.; Yang, J.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Preparation of High-Barrier Performance Paper-Based Materials from Biomass-Based Silicone-Modified Acrylic Polymer Emulsion. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 3348–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.-Z.; Zhao, H.; Huang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, S.; Chen, Y. Designing and Regulating Catalysts for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution in Acid Electrolytes. Carbon Neutralization 2023, 2, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.A.; Cabling, L.P.B.; Leonard, N.A.; Dubrawski, K.L.; Buckley, H.L. Green Alginate Extraction from Macrocystis pyrifera for Bioplastic Applications: Physicochemical, Environmental Impact, and Chemical Hazard Analyses. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, S.; Johnson, T.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Zamani, E.; Dishari, S.K. Ionomers From Kraft Lignin for Renewable Energy Applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, F.B.; McMichael, P.S.; Whitbeck, A.; Jalaee, A.; Gyenge, E.; Foster, E.J. Proton Exchange Membranes from Sulfonated Lignin Nanocomposites for Redox Flow Battery Applications. Small 2024, 20, 2309459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliaeva, K.; Elsheref, M.; Walden, D.; Dappozze, F.; Nieto-Marquez, A.; Gil, S.; Guillard, C.; Steinmann, S.N.; Vernoux, P.; Caravaca, A. Towards Understanding Lignin Electrolysis: Electro-Oxidation of a β-O-4 Linkage Model on PtRu Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 134511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; De, B.S.; Singh, A.; Shahgaldi, S. Lignin Electrolysis at Room Temperature on Nickel Foam for Hydrogen Generation: Performance Evaluation and Effect of Flow Rate. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.N.; Manuvalli, B.B.; Kariduraganavar, M.Y. A Unique Approach for the Development of Hybrid Membranes by Incorporating Functionalized Nanosilica into Crosslinked sPVA/TEOS for Fuel Cell Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 9823–9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, K.; Danilovic, N.; Harrison, K.; Xu, H. PEM Electrolysis, a Forerunner for Clean Hydrogen. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2021, 30, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthurs, C.; Kusoglu, A. Compressive Creep of Polymer Electrolyte Membranes: A Case Study for Electrolyzers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 3249–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulas, D.; Handler, R.; Tindall, G.; Lynn, B.; Thies, M.; Shonnard, D. Economic and Environmental Impact of Recovering and Upgrading Lignin via the ALPHA Process on an Ethanol Biorefinery. Sustain. Sci. Technol. 2025, 2, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.J.; Lee, E.; Lee, J.Y.; Yu, D.M.; Yoon, S.J.; Oh, K.-H.; Hong, Y.T.; So, S. Multi-Block Copolymer Membranes Consisting of Sulfonated Poly(p-Phenylene) and Naphthalene Containing Poly(Arylene Ether Ketone) for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. Polymers 2023, 15, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Lv, P.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q. Sulfonate and Ammonium-Grafted Poly(Isatin Triphenyl) Membranes for the Vanadium Redox Flow Battery. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 10727–10737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, M.; Peressin, N.; Holdcroft, S. On the Evolution of Sulfonated Polyphenylenes as Proton Exchange Membranes for Fuel Cells. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 4966–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yin, J.; Liu, M.; Tolj, I.; Grigoriev, S.A.; Ge, M.; Sun, C. Investigations of the Sulfonated Poly(Ether Ether Ketone) Membranes with Various Degrees of Sulfonation by Considering Durability for the Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hwang, S.; Jeong, Y.-G.; Choi, Y.-S.; Kim, K. Cross-Linked Sulfonated Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) Membrane Using Polymeric Cross-Linkers for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell Applications. Membranes 2023, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Han, J.; Ahn, S.M.; Jeong, H.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, K.; Lee, J.-C. Simple and Effective Cross-Linking Technology for the Preparation of Cross-Linked Membranes Composed of Highly Sulfonated Poly(Ether Ether Ketone) and Poly(Arylene Ether Sulfone) for Fuel Cell Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 10495–10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarizia, G.; Bernardo, P. Polyether Block Amide as Host Matrix for Nanocomposite Membranes Applied to Different Sensitive Fields. Membranes 2022, 12, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, R.A.; Aisyah, H.A.; Nordin, A.H.; Ngadi, N.; Zuhri, M.Y.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zainudin, E.S.; Sharma, S.; Abral, H.; et al. Natural-Fiber-Reinforced Chitosan, Chitosan Blends and Their Nanocomposites for Various Advanced Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, M.; Bellali, F.; Karrat, A.; Bouchdoug, M.; Jaouad, A.; Kharroubi, M.; Bellali, F.; Karrat, A.; Bouchdoug, M.; Jaouad, A. Preparation of Teucrium polium Extract-Loaded Chitosan-Sodium Lauryl Sulfate Beads and Chitosan-Alginate Films for Wound Dressing Application. AIMSPH 2021, 8, 754–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, T.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; He, J.; Yin, C. Preparation and Characterization of Cellulose Carbamate Membrane with High Strength and Transparency. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasino, D.V.; Wolf, M.; Farina, H.; Chiarello, G.; Feldhoff, A.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Sabatini, V. Role of Doping Agent Degree of Sulfonation and Casting Solvent on the Electrical Conductivity and Morphology of PEDOT:SPAES Thin Films. Polymers 2021, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.; Améduri, B.; Kulshrestha, V. Proton-Conducting γ-Sulfopropyl Acrylate Tethered Halato-Telechelic PVDF Membranes for Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacorte, D.H.; Valério Filho, A.; Carvalho, M.D.; Avila, L.B.; Moraes, C.C.; Rosa, G.S.d. Optimization of the Green Extraction of Red Araçá (Psidium catteyanum Sabine) and Application in Alginate Membranes for Use as Dressings. Molecules 2023, 28, 6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, V.N.; Phong, L.P.N.; Van Nhi, N.; Van, T.T.T.; Nhan, H.T.C.; Van Hieu, L. Effect of Imidazole-Doped Nanocrystalline Cellulose on the Characterization of Nafion Films of Fuel Cells. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 3114–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, F.; Lou, J.; Ilias, S. Application of Nanoparticles in Modified Polybenzimidazole-Based High Temperature Proton Exchange Membranes. J. Elastomers Plast. 2023, 55, 1152–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Wong, W.Y.; Loh, K.S.; Khalid, M.; Daud, W.R.W.; Lim, K.L.; Walvekar, R. Enhancement in Hydrolytic Stability and Proton Conductivity of Optimised Chitosan/Sulfonated Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Composite Membrane with Inorganic Fillers. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 21307–21323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.M.; Patnaik, P.; Sharma, R.; Sarkar, S.; Chatterjee, U. Unveiling CeZnOx Bimetallic Oxide: A Promising Material to Develop Composite SPPO Membranes for Enhanced Oxidative Stability and Fuel Cell Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 7097–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzapioda, L.; Lo Vecchio, C.; Danyliv, O.; Baglio, V.; Martinelli, A.; Navarra, M.A. Composite Nafion-CaTiO3-δ Membranes as Electrolyte Component for PEM Fuel Cells. Polymers 2020, 12, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Khalid, M.; Shahgaldi, S. Advanced Electrocatalyst Supports for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers. ACS Energy Lett. 2024, 9, 2922–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnik, N.; Romano, L.; Jovanovič, P.; Ruiz-Zepeda, F.; Bele, M.; Fabbri, F.; Persano, L.; Camposeo, A.; Pisignano, D. Assembly of Pt Nanoparticles on Graphitized Carbon Nanofibers as Hierarchically Structured Electrodes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 9880–9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.C.; Gabardo, C.M.; Liu, S.; Lee, G.; Zhao, Y.; O’Brien, C.P.; Miao, R.K.; Xu, Y.; Edwards, J.P.; Fan, M.; et al. Direct Carbonate Electrolysis into Pure Syngas. EES Catalysis 2023, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinothkannan, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Kim, A.R.; Lee, H.-K.; Yoo, D.J. Ceria Stabilized by Titanium Carbide as a Sustainable Filler in the Nafion Matrix Improves the Mechanical Integrity, Electrochemical Durability, and Hydrogen Impermeability of Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells: Effects of the Filler Content. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 5704–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selyanchyn, O.; Selyanchyn, R.; Lyth, S.M. A Review of Proton Conductivity in Cellulosic Materials. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 596164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jun, J.H.; Park, M.; Jeong, J.; Jo, J.-H.; Jeon, S.; Yang, J.; Choi, S.M.; Jo, W.; Lee, J.-H. Hierarchically Designed Co4Fe3@N-Doped Graphitic Carbon as an Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Evolution in Anion-Exchange-Membrane Water Electrolysis. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 4451–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, P.; Shao, Q.; Huang, X. Recent Progress in Advanced Electrocatalyst Design for Acidic Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmachowski, P.; Duch, J.; Sebastián, D.; Lázaro, M.J.; Kotarba, A. Carbon-Based Composites as Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Alkaline Media. Materials 2021, 14, 4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Tao, H.; Liu, B. Progress of Nonprecious-Metal-Based Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution in Acidic Media. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2003786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, L.A.; Kumar, K.; Martin, V.; Maillard, F.; Maugé, F.; Portier, X.; Oliviero, L.; Dubau, L. Direct Evidence of the Role of Co or Pt, Co Single-Atom Promoters on the Performance of MoS2 Nanoclusters for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selyanchyn, O.; Bayer, T.; Klotz, D.; Selyanchyn, R.; Sasaki, K.; Lyth, S.M. Cellulose Nanocrystals Crosslinked with Sulfosuccinic Acid as Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes for Electrochemical Energy Applications. Membranes 2022, 12, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Jeon, Y.; Park, J.; Shul, Y.-G. Nano-Composite Filler of Heteropolyacid-Imidazole Modified Mesoporous Silica for High Temperature PEMFC at Low Humidity. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harun, N.A.M.; Shaari, N.; Nik Zaiman, N.F.H. A Review of Alternative Polymer Electrolyte Membrane for Fuel Cell Application Based on Sulfonated Poly(Ether Ether Ketone). Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 19671–19708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhao, X.; Su, G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, K.; Zhu, H. Synthesis and Electrocatalytic Performance of a P-Mo-V Keggin Heteropolyacid Modified Ag@Pt/MWCNTs Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Ionics 2019, 25, 5141–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Aili, D.; Lu, S.; Li, Q.; Jiang, S.P. Advancement toward Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells at Elevated Temperatures. Research 2020, 2020, 9089405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Đelević, L.; Herkendell, K. Next-Generation Proton-Exchange Membranes in Microbial Fuel Cells: Overcoming Nafion’s Limitations. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2301346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, D.; Akcora, P. Ion-Containing Polymer-Grafted Nanoparticles in Ionic Liquids: Implications for Polymer Electrolyte Membranes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 8108–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenbücher, C.; Korte, C.; Chen, Y.; Wippermann, K.; Kowalski, P.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Hempelmann, R.; Kim, B. High-Temperature Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells Based on Protic Ionic Liquids. Fuel Cells 2024, 24, e202300213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensharapov, R.M.; Ivanova, N.A.; Bakirov, A.V.; Semkina, A.S.; Patsaev, T.D.; Sinyakov, M.V.; Klein, O.I.; Dmitryakov, P.V.; Zhang, C.; Spasov, D.D. Effects of Sol–Gel Modification on the Microstructure of Nafion Membranes. Polymers 2025, 17, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anis, A.; Alam, M.; Alhamidi, A.; Gupta, R.K.; Tariq, M.; Al-Zahrani, S.M. Studies on Polybenzimidazole and Methanesulfonate Protic-Ionic-Liquids-Based Composite Polymer Electrolyte Membranes. Polymers 2023, 15, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.T.E.; Abdul Rahim, A.R.; Masdar, M.S.; Shyuan, L.K. Enhanced Performance of Polymer Electrolyte Membranes via Modification with Ionic Liquids for Fuel Cell Applications. Membranes 2021, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyalı, E.; Cengiz, H.Y.; Müftüler, A.; Deligöz, H. Monitoring the Salt Stability and Solvent Swelling Behavior of PAH-Based Polyelectrolyte Multilayers by Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 3328–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.; Dubelley, F.; Paul, A.; Svecova, L.; Bas, C. Investigation of Membrane–Electrode Separation Processes for the Recycling of Ionomer Membranes in End-of-Life PEM Fuel Cells. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 2758–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, M.; Goes, D.; Ahn, S.; Vrucak, D.; Gießmann, T.; Bauer-Siebenlist, B.; Leißner, T.; Rudolph, M.; Fleischer, J.; Friedrich, B.; et al. Conceptual Recycling Chain for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers—Case Study Involving Review-Derived Model Stack. Recycling 2025, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, M.A.; Vankelecom, I.F.J. γ-Valerolactone as Bio-Based Solvent for Nanofiltration Membrane Preparation. Membranes 2021, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, P.K.; Mistry, R.; Saxena, M.; Nandha, N.; Thummar, U.; Kumar, P.; Singh, P.S. Increase of Flow-through Pores in Rationally Designed Organosilica-PVDF Nanocomposite Membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkandari, S.H.; Castro-Dominguez, B. Electro-Casting for Superior Gas Separation Membrane Performance and Manufacturing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 56600–56611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielen, W.M.; Willott, J.D.; Galicia, J.A.R.; de Vos, W.M. Effect of Solution Viscosity on the Precipitation of PSaMA in Aqueous Phase Separation-Based Membrane Formation. Polymers 2021, 13, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Chen, Y.; Kong, Y.-R.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H.-B.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Ren, X.-M. Metal–Organic Framework-Derived N-Doped Porous Carbon for a Superprotonic Conductor at above 100 °C. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 20057–20063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.-R.; Lee, K.-S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.-K. A Highly Active and Stable 3D Dandelion Spore-Structured Self-Supporting Ir-Based Electrocatalyst for Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis Fabricated Using Structural Reconstruction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 3449–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seol, C.; Jang, S.; Lee, J.; Nam, L.V.; Pham, T.A.; Koo, S.; Kim, K.; Jang, J.-H.; Kim, S.M.; Yoo, S.J. High-Performance Fuel Cells with a Plasma-Etched Polymer Electrolyte Membrane with Microhole Arrays. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 5884–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Ulsh, M.; Mackay, J.; Harris, T.; Shrivastava, N.; Chatterjee, A.; Porter, J.; Bender, G. The Effect of Membrane Casting Irregularities on Initial Fuel Cell Performance. Fuel Cells 2020, 20, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, L.; Zhakisheva, B.; Sgreccia, E.; Narducci, R.; Di Vona, M.L.; Knauth, P. Stability of Proton Exchange Membranes in Phosphate Buffer for Enzymatic Fuel Cell Application: Hydration, Conductivity and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2021, 13, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panawong, C.; Tasarin, S.; Saejueng, P.; Budsombat, S. Composite Proton Conducting Membranes from Crosslinked Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Chitosan and Silica Particles Containing Poly(2-Acrylamido-2-Methyl-1-Propansulfonic Acid). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, D.; Yang Lee, J.; Hong, L. Hydrophilic Cross-Linked Aliphatic Hydrocarbon Diblock Copolymer as Proton Exchange Membrane for Fuel Cells. Materials 2021, 14, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Amin, N.H.; Junaidi, M.U.M.; Amir, Z.; Hashim, N.A.; Hizaddin, H.F.; Ahmad, A.L.; Zainal Abidin, M.I.I.; Rabuni, M.F.; Syed Nor, S.N. Diamine-Crosslinked and Blended Polyimide Membranes: An Emerging Strategy in Enhancing H2/CO2 Separation. Polymers 2025, 17, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Chiu, C.-C. Solute Diffusivity and Local Free Volume in Cross-Linked Polymer Network: Implication of Optimizing the Conductivity of Polymer Electrolyte. Polymers 2022, 14, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Peng, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, G.; Xiao, L.; Lu, J.; Zhuang, L. Ultrathin Self-Cross-Linked Alkaline Polymer Electrolyte Membrane for APEFC Applications. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 4297–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odess, A.; Cohen, M.; Li, J.; Dantus, M.; Zussman, E.; Freger, V. Electrospun Ion-Conducting Composite Membrane with Buckling-Induced Anisotropic Through-Plane Conductivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 35700–35708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, A.M.; Hacker, V. QPVA-Based Electrospun Anion Exchange Membrane for Fuel Cells. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2023, 12, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C. Sulfonated Poly (Ether Ether Ketone)-Filled Nanofiber-Based Composite Proton Exchange Membranes for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, R.R.; Park, M.J.; Tijing, L.; Han, D.S.; Phuntsho, S.; Shon, H.K. Modification of Nanofiber Support Layer for Thin Film Composite Forward Osmosis Membranes via Layer-by-Layer Polyelectrolyte Deposition. Membranes 2018, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, H.M.; Kadavil, H.; Ismail, H.M.; Adib, S.A.; Zamani, S.; Alany, R.G.; Al-Kinani, A.A. Overview of Tissue Engineering and Drug Delivery Applications of Reactive Electrospinning and Crosslinking Techniques of Polymeric Nanofibers with Highlights on Their Biocompatibility Testing and Regulatory Aspects. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.D.; Hasan, M.M.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Rashid, M.J. Electrospun Nanofiber-Based Electrolytes for Next-Generation Quasi-Solid Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: A Review. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 14797–14838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, R.; Khaliq, J.; Combrinck, M.; Hassanin, A.H.; Shehata, N.; Elnabawy, E.; Shyha, I. Solution Blow Spinning of Polyvinylidene Fluoride Based Fibers for Energy Harvesting Applications: A Review. Polymers 2020, 12, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Singh, K.; Dixit, R.J.; De, B.S.; Basu, S. Co-Generation of Hydrogen and FDCA from Biomass-Based HMF in a 3D-Printed Flow Electrolyzer. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 21180–21189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wippermann, K.; Rasinski, M.; Suo, Y.; Shviro, M.; Carmo, M.; Lehnert, W. Constructing a Multifunctional Interface between Membrane and Porous Transport Layer for Water Electrolyzers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 16182–16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, M.R.; Østenstad, J.S.; Barnett, A.O.; Thomassen, M.S. Modeling Contact Resistance and Water Transport within a Cathode Liquid-Fed Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 124516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Li, M.; Yin, Y.; Du, R.; Tan, X.; Zhong, Q.; Zeng, F. Development of a Self-Pressurized Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Electrolyzer for Hydrogen Production at High Pressures. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2025, 48, e202400121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradinaru, S.; Tabaras, D.; Gheorghe, D.; Zamfir, R.; Vasilescu, M.; Grigorescu, G.; Cristescu, I. Analysis of the anisotropy for 3D printed pla parts usable in medicine. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B Chem. Mater. Sci. 2019, 81, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.P.; Redondo, E.; Pumera, M. 3D Printing for Electrochemical Energy Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2783–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüner, B.; Kıstı, M.; Uysal, S.; Uzgören, İ.N.; Özdoğan, E.; Süzen, Y.O.; Demir, N.; Kaya, M.F. An Overview of Various Additive Manufacturing Technologies and Materials for Electrochemical Energy Conversion Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 40638–40658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golubkov, S.S.; Morozova, S.M. Recent Progress of 3D Printing of Polymer Electrolyte Membrane-Based Fuel Cells for Clean Energy Generation. Polymers 2023, 15, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Tanaka, M.; Kuramochi, M.; Yamanouchi, S.; Miyaguchi, N.; Kawakami, H. Development of Blend Nanofiber Composite Polymer Electrolyte Membranes with Dual Proton Conductive Mechanism and High Stability for Next-Generation Fuel Cells. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 5177–5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Tanioka, A.; Matsumoto, H. De Novo Ion-Exchange Membranes Based on Nanofibers. Membranes 2021, 11, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.K.; Jain, P.K.; Kumar, P.; Pegoretti, A.; Bowen, C.R. Smart Manufacturing Process of Carbon-Based Low-Dimensional Structures and Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites for Engineering Applications. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 4162–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Araya, S.S.; Cui, X.; Kær, S.K. The Effects of Cationic Impurities on the Performance of Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzer. J. Power Sources 2020, 473, 228617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pan, Q.; Liang, X.; Zou, X. Ensuring Stability of Anode Catalysts in PEMWE: From Material Design to Practical Application. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Garcia, I.; Velizarov, S. New Insights into the Definition of Membrane Cleaning Strategies to Diminish the Fouling Impact in Ion Exchange Membrane Separation Processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 277, 119445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.A.; King, L.A.; Jaramillo, T.F. Evaluating the Case for Reduced Precious Metal Catalysts in Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolyzers. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Xu, S.; Sun, C. Deep Learning-Based State-of-Health Estimation of Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells under Dynamic Operation Conditions. Sensors 2024, 24, 4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, J.; Janßen, H.; Yassin, K.; Leppin, J.; Choi, Y.-W.; Cha, J.-E.; Wark, M.; Brandon, S.; Dekel, D.R.; Harms, C.; et al. Impact of the Relative Humidity on the Performance Stability of Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells Studied by Ion Chromatography. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 3962–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpatova, A.; Qamar, A.; Al-Ghamdi, M.; Lee, J.; Ghaffour, N. Effective Membrane Backwash with Carbon Dioxide under Severe Fouling and Operation Conditions. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 611, 118290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, N.; Hirsch, U.M.; Steinert, C.; Fritzsche, G.; Schmelzer, C.E.H. Plasma-Enhanced Magnetron Sputtering: A Novel Approach for Biofunctional Metal Nanoparticle Coatings on Reverse Osmosis Composite Membranes. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 11, 2400461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, B.; Ma, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, D. Performance Analysis Based on Sustainability Exergy Indicators of High-Temperature Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klose, C.; Saatkamp, T.; Münchinger, A.; Bohn, L.; Titvinidze, G.; Breitwieser, M.; Kreuer, K.-D.; Vierrath, S. All-Hydrocarbon MEA for PEM Water Electrolysis Combining Low Hydrogen Crossover and High Efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komers, F.; Plachá, D.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Velizarov, S. Towards Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes: Materials and Challenges for Water Electrolysis. Water 2025, 17, 3297. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223297

Komers F, Plachá D, Van der Bruggen B, Velizarov S. Towards Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes: Materials and Challenges for Water Electrolysis. Water. 2025; 17(22):3297. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223297

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomers, Filip, Daniela Plachá, Bart Van der Bruggen, and Svetlozar Velizarov. 2025. "Towards Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes: Materials and Challenges for Water Electrolysis" Water 17, no. 22: 3297. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223297

APA StyleKomers, F., Plachá, D., Van der Bruggen, B., & Velizarov, S. (2025). Towards Sustainable Proton Exchange Membranes: Materials and Challenges for Water Electrolysis. Water, 17(22), 3297. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223297