1. Introduction

The Chesapeake Bay (CB) watershed, located in the Mid-Atlantic region, is the largest estuary in the United States [

1]. The CB coastal region, which spans across Maryland and Virginia, faces significant threats from rising sea levels and land subsidence (LS). Relative sea-level change (RSLC) in this area is driven by the combined effects of global mean sea-level rise (GMSLR), regional sea-level rise (RSLR), and local LS. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) linear simulation results indicate that sea levels are rising at rates between 3.24 and 6.04 mm/year at 15 tide gauges (TGs) along the CB coast [

2], with recent satellite imagery revealing accelerated subsidence rates exceeding 5.1 mm/year in some locations [

3,

4]. The consequences of this accelerating RSLC are already evident in shoreline erosion, inundation, increased tidal flooding, saline intrusion, and the loss of valuable wetland ecosystems [

5].

Over the past 150 years, approximately 42.5 km

2 of island habitats have been lost in the middle-eastern portion of CB, and future projections suggest that, without intervention, many of these remote island habitats will disappear within 20 years [

6]. In Annapolis, the frequency of nuisance tidal flooding has risen dramatically—from just a few days per year in the 1950s to 40 or more days annually [

7]. These changes not only threaten coastal ecosystems but also put human populations and infrastructure at risk. Under the Current Commitments scenario (SSP2–4.5) [

8], the best estimate of sea-level rise in 2100 in Maryland is 0.8 m (2.7 ft, from a 2005 starting point) and sea level will likely rise between 0.6 m (2.0 ft) and 1.1 m (3.5 ft), barring unexpected processes driving rapid ice sheet melting [

5]. By 2100, more than 68,000 residential properties—home to approximately 102,000 people—in Maryland alone are projected to be at risk of chronic inundation due to tidal flooding and critical infrastructure in both Maryland and Virginia, including industrial sites, public health and safety buildings, and energy infrastructure, will require significant adaptation or relocation [

9].

In Part 1 of this study [

10], we introduced a comprehensive methodology to analyze RSLC in CB by integrating GMSLR, RSLR, and LS using TG data, satellite altimetry, and geoscientific information. The framework distinguished between bedrock-surface subsidence (BSS) and compaction subsidence (CS), with CS further categorized into primary consolidation subsidence (PCS), secondary consolidation subsidence (SCS), construction-induced subsidence (CIS), and negative subsidence (NS).

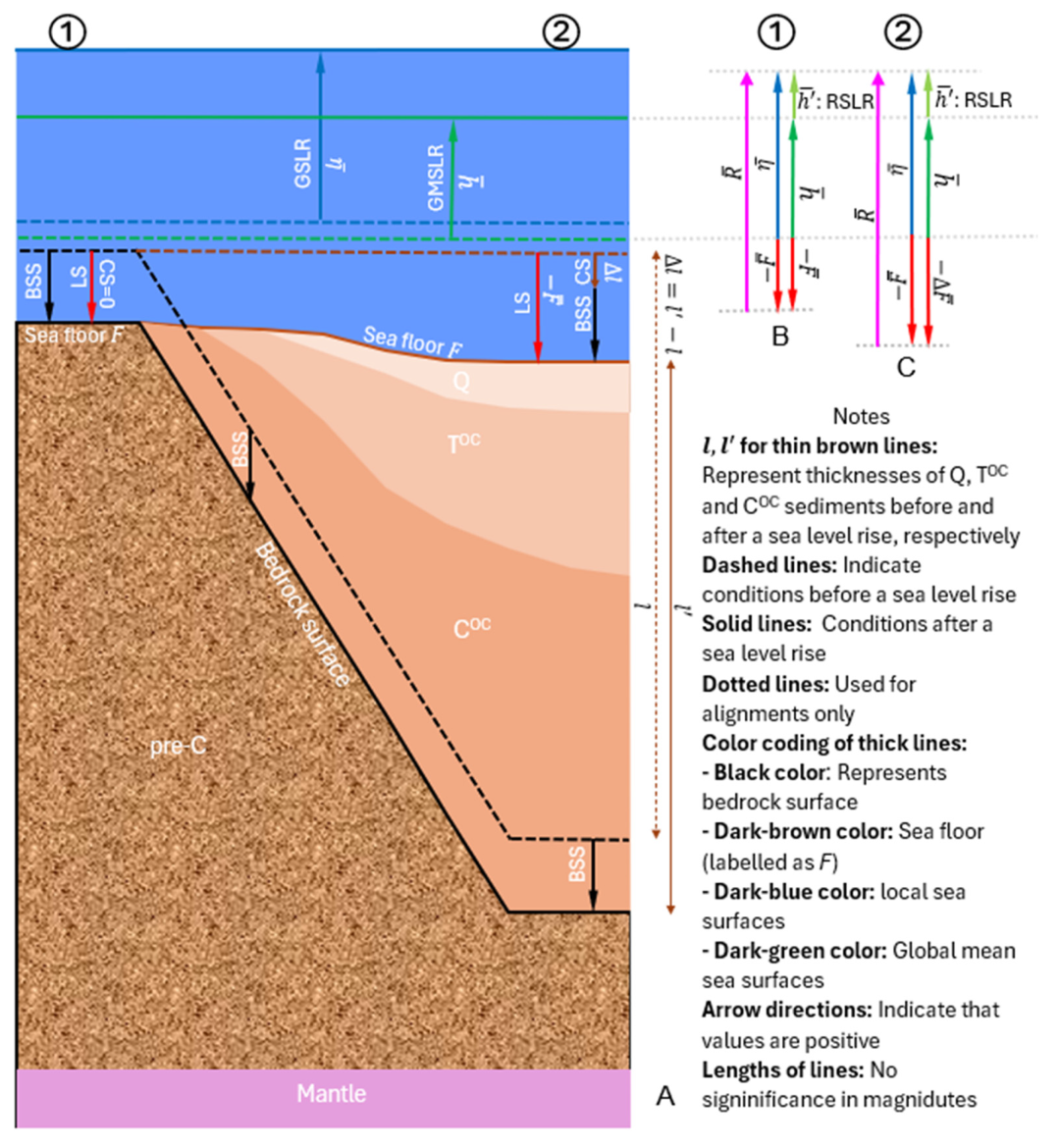

Figure A1 in

Appendix A provides a conceptual overview of the trend relationships between RSLC, LS, RSLR, and GMSLR in CB, illustrating how these processes interact at different TG locations in Part 1. We propose a general relationship in which RSLC at the ocean point of interest is the combination of GMSLR, RSLR, and LS. At location ①, LS is equivalent to bedrock-surface subsidence (BSS) at the bedrock sea floor (pre-C: Jurassic to Precambrian) sea floor, whereas at location ②, LS is the sum of compaction subsidence (CS) and BSS at the compressible sediment sea floor (see sea floor used in [

11]). This conceptual framework forms the basis for the analysis and results presented in Part 2. The framework assumes that both trends of GMSLR and RSLR are linear before 1992 and quadratic since 1992 [

12] and LS trends are simply linear (see

Appendix B).

In Part 2, we apply the concepts and methodologies established in Part 1 to derive and present key findings based on statistical extrapolation of observed tide gauge trends, rather than on climate model-based sea-level projections. Specifically: (1) Global mean sea-level trend and acceleration: We suggest the best estimate of the linear constant of GMSLR (

) (i.e.,

in Equation (A2a)) since 1900 by synthesizing previous results and presenting an estimate of the acceleration of GMSLR (

) (i.e.,

in Equation (A2b)), which can be related to climate scenarios [

13] from 1992 to 2022, based on trend analyses derived from global ocean satellite altimetry observations. (2) Regional Seal-Level Rise (RSLR) Trend and Acceleration: We estimate the linear constant (

in Equation (A3a)) and acceleration (

in Equation (A3b)) of RSLR (

) in CB to identify deviations from GMSLR. (3) Bedrock Surface Subsidence (BSS) Contour Map: We present a BSS contour map (

Figure 1) to illustrate glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA)-induced subsidence in the region. This map is derived from LS data at four TG stations—Baltimore, Washington D.C., Ocean City, and Kiptopeke—where CS is negligible based on geological or hydrogeological conditions. (4) Compaction Subsidence (CS): We quantify CIS at Kiptopeke and PCS at 10 other short-term TG locations by isolating CS from total LS using interpolated BSS values from the contour map. (5) Relative Sea-Level (RSL) Trend Projections: We present RSLC trend projection results at 15 TG locations and provide insights into future risks and implications for coastal resilience planning. Those projections are an extrapolation of the linear and quadratic trends of a polynomial fit of historical observations. (6) Discussion: Finally, we discuss the baseline of relative sea level (RSL), uncertainty of RSL trends, the accelerations of GMSLR and geocentric sea-level change (GSLC), the linear constant and quadratic acceleration of RSLR, a comparison with historically identified LS, and the application of BSS to estimate primary consolidation subsidence (PCS) from other LS measurements. We conclude with a summary of key findings and future research directions.

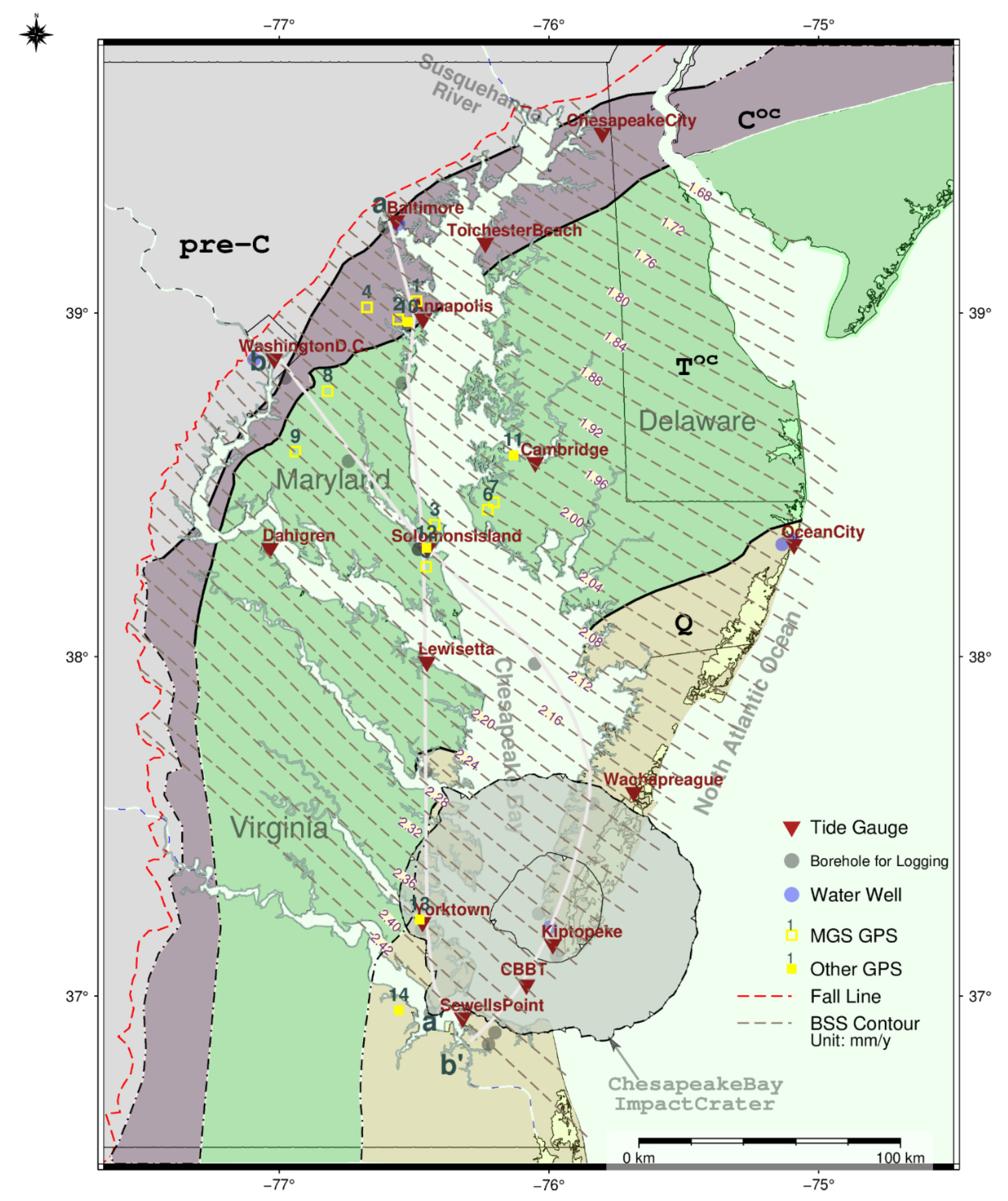

Figure 1.

Bedrock surface subsidence (BSS) contour map overlaid on the CB geological basemap. This map highlights TG locations, boreholes for well logging, groundwater pumping wells, and GPS stations used in this study. Cross-sections a-a′ and b-b′, including boreholes near TGs, are depicted in

Figure 2. Data of the 15 TGs (red inverted triangles) were obtained from the NOAA [

2]. The lithological information for 15 boreholes (gray circle) in Maryland (seven borehole loggings in

Supplementary Figure S1A–G; hydrogeology in

Supplementary Table S1) and Virginia (eight borehole logging data in

Table S2) could be referred to references [

14,

15]. The groundwater level time series for eight groundwater wells, located 2.5 to 7.5 km away from their corresponding TG stations, are presented in

Supplementary Figure S2. The boundary of the main rivers and CB was obtained from [

16]. The fall line information was acquired from ArcGIS Online (Esri, accessed 2023) [

17], and the location of the CB impact crater was derived from reference [

18]. The fall line is a geologic and geographic boundary in the Chesapeake Bay region where the hard, crystalline rocks of the Piedmont plateau meet the soft, sedimentary soils of the Coastal Plain.

Figure 1.

Bedrock surface subsidence (BSS) contour map overlaid on the CB geological basemap. This map highlights TG locations, boreholes for well logging, groundwater pumping wells, and GPS stations used in this study. Cross-sections a-a′ and b-b′, including boreholes near TGs, are depicted in

Figure 2. Data of the 15 TGs (red inverted triangles) were obtained from the NOAA [

2]. The lithological information for 15 boreholes (gray circle) in Maryland (seven borehole loggings in

Supplementary Figure S1A–G; hydrogeology in

Supplementary Table S1) and Virginia (eight borehole logging data in

Table S2) could be referred to references [

14,

15]. The groundwater level time series for eight groundwater wells, located 2.5 to 7.5 km away from their corresponding TG stations, are presented in

Supplementary Figure S2. The boundary of the main rivers and CB was obtained from [

16]. The fall line information was acquired from ArcGIS Online (Esri, accessed 2023) [

17], and the location of the CB impact crater was derived from reference [

18]. The fall line is a geologic and geographic boundary in the Chesapeake Bay region where the hard, crystalline rocks of the Piedmont plateau meet the soft, sedimentary soils of the Coastal Plain.

![Water 17 03235 g001 Water 17 03235 g001]()

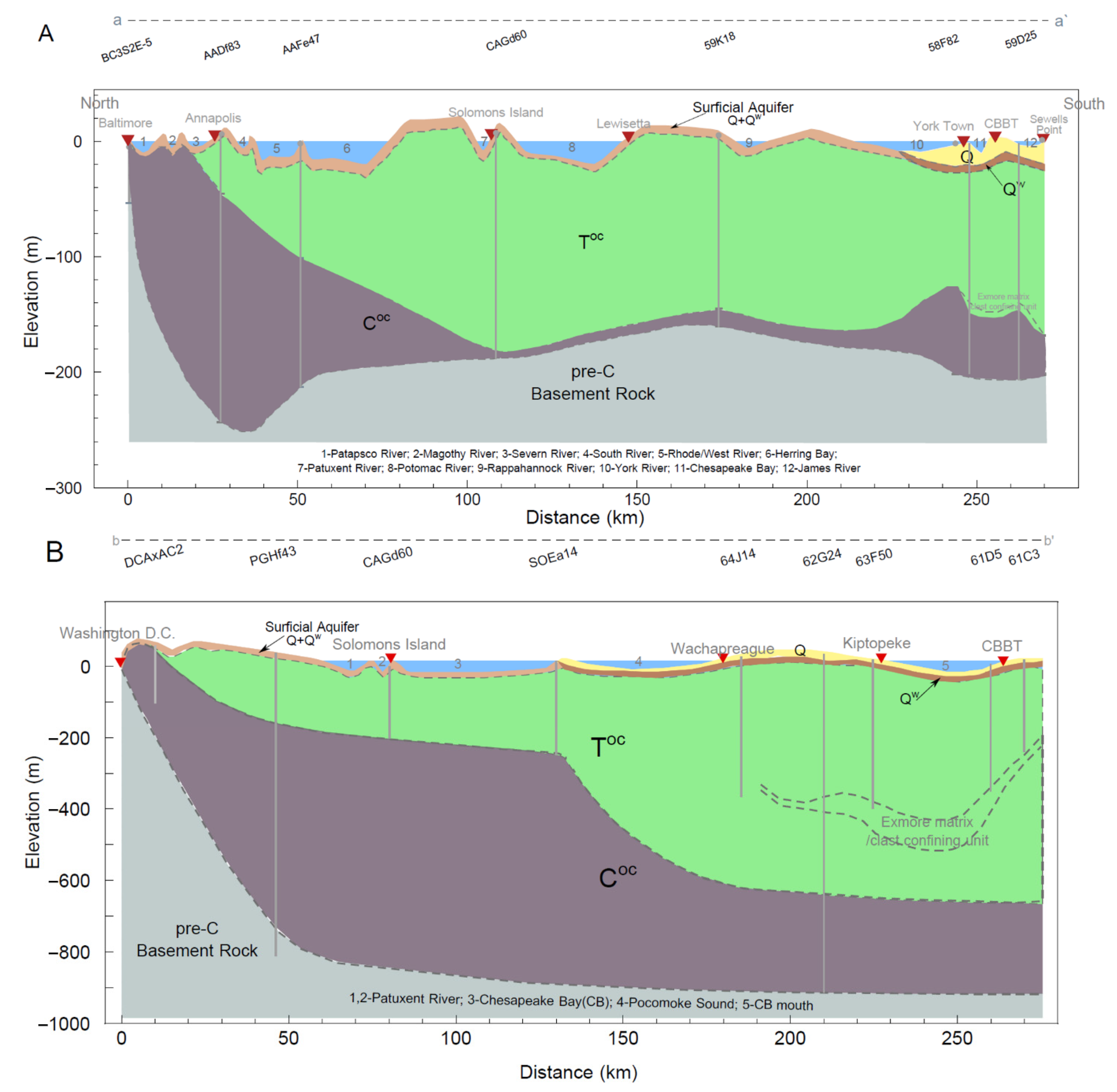

Figure 2.

Geological cross-sections a-a′ (

A) and b-b′ (

B). Cross-section a-a′ connects six TGs [Baltimore, Annapolis, Solomons Island, Lewisetta, York Town, CBBT (CB Bridge Tunnel), and Swells Point] while cross-section b-b′ connects five TGs (Washington D.C., Solomons Island, Wachapreague, Kiptopeke, and CBBT) in

Figure 1. The geological strata depth information is from references [

15,

19]. See

Supplementary Table S3 for geological strata symbols and

Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S2 for the geological logs’ information. Different colors represent major geological units (yellow = Quaternary (

) deposits, where light yellow indicates the exposed Quaternary strata, yellow-brown represents the weathered surficial layer (

), and the light yellow-brown represents the mixed zone (

); green = Tertiary (

), grayish brown = Cretaceous (

), and silver gray = pre-Cretaceous basement rock (pre-C: Juaassic-Precambrian)). Letters (a, a′, b, b′) mark the start and end points of each cross-section. Borehole IDs (BC5525, AA0813, and AN8471, etc.) correspond to locations of geological logs.

Figure 2.

Geological cross-sections a-a′ (

A) and b-b′ (

B). Cross-section a-a′ connects six TGs [Baltimore, Annapolis, Solomons Island, Lewisetta, York Town, CBBT (CB Bridge Tunnel), and Swells Point] while cross-section b-b′ connects five TGs (Washington D.C., Solomons Island, Wachapreague, Kiptopeke, and CBBT) in

Figure 1. The geological strata depth information is from references [

15,

19]. See

Supplementary Table S3 for geological strata symbols and

Supplementary Figure S1 and Table S2 for the geological logs’ information. Different colors represent major geological units (yellow = Quaternary (

) deposits, where light yellow indicates the exposed Quaternary strata, yellow-brown represents the weathered surficial layer (

), and the light yellow-brown represents the mixed zone (

); green = Tertiary (

), grayish brown = Cretaceous (

), and silver gray = pre-Cretaceous basement rock (pre-C: Juaassic-Precambrian)). Letters (a, a′, b, b′) mark the start and end points of each cross-section. Borehole IDs (BC5525, AA0813, and AN8471, etc.) correspond to locations of geological logs.

![Water 17 03235 g002 Water 17 03235 g002]()

2. Global Mean Sea-Level Trend and Acceleration

To determine the RSLR (

) in the CB area, it is essential to estimate the linear constant of GMSLR trends (

) during 1900–1992 (i.e.,

in Equations (A2a) and (A2b) in

Appendix B and its acceleration since 1992 (i.e.,

in Equation (A2b) [

12,

20,

21]. It is ‘very likely’ (probability 90%) that the linear constant

for the period 1901–1990 ranged from 1.0 to 1.4 mm/year based on a probabilistic reanalysis [

22], compared to a range from 0.78 to 1.92 mm/year based on paleoreconstructions, instrumental observations, model simulations [

23], and an ensemble approach [

24]. In the literature since the 1970s, there have been six representative assessments of the linear constant. In 1974, the earliest GMSLR research estimated the eustatic or worldwide SLR at 1.0 mm/year [

25]. This 1st estimate was used for deriving LS at 9 TGs along the coast of Gulf of Mexico and eight TGs along the CB coast without introducing the concept of RSLR (

). In the past three decades, GMSLR research using long-term TG data worldwide found a GMSLR trend of approximately 1.8 mm/year for the 20th century, which is the 2nd estimate [

26,

27,

28]. The 3rd estimate of 1.7 mm/year was derived from data over the 1950–2000 period [

29,

30]. The 4th estimate is 1.90 mm/year for the 1901–1990 period, based on the reconstruction of global sea level from TG records [

31]. The 5th estimate is 1.20 mm/year from 1901 to 1990, using probabilistic techniques [

22]. The latest, 6th GMSLR rate was estimated to be 1.1 mm/year during the period 1902–1990 from a 20th-century GMSL reconstruction, employing an area-weighting technique that incorporates up-to-date observations of VLM and corrections for local geoid changes due to ice melting and terrestrial freshwater storage [

32].

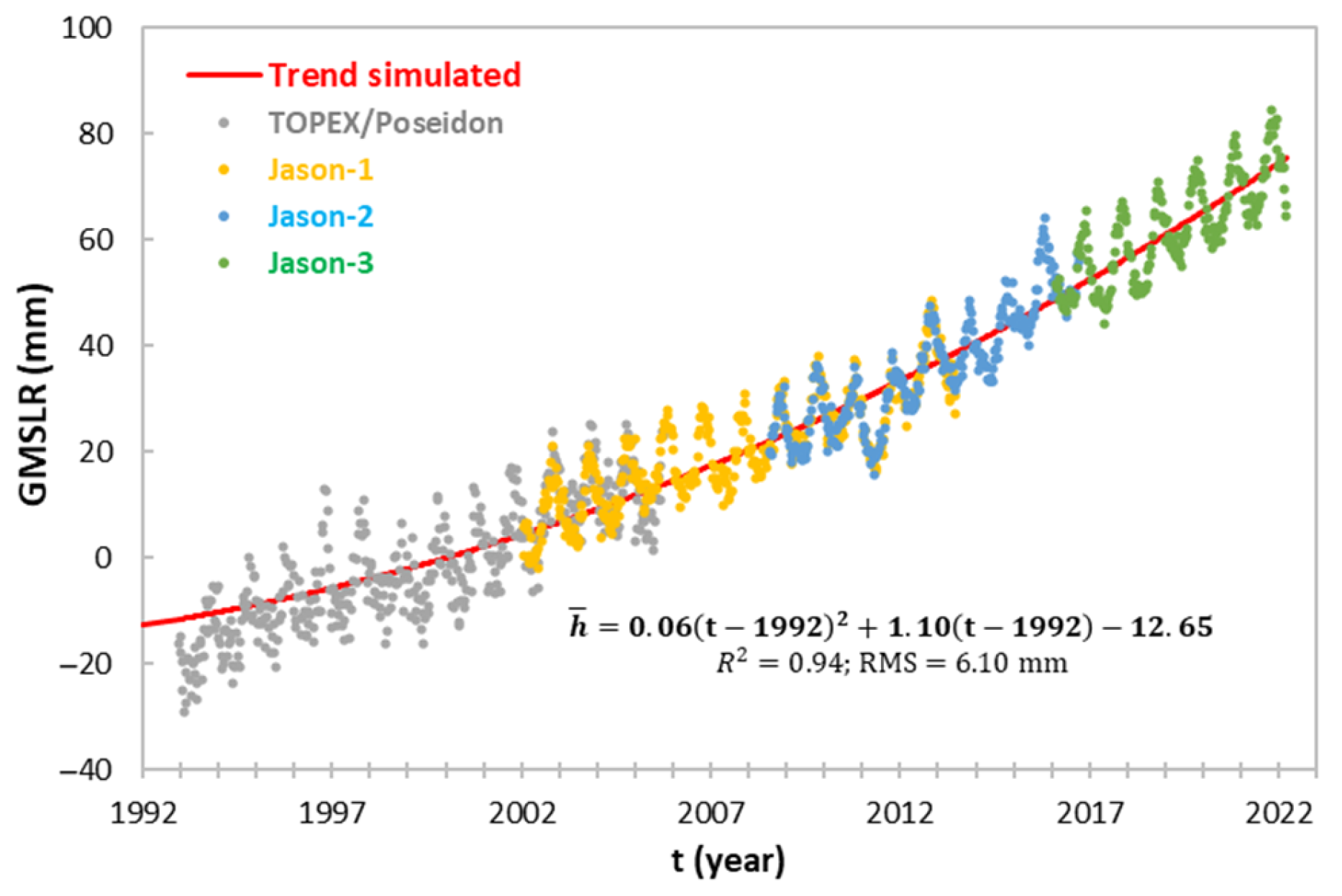

Figure 3 illustrates the quadratic feature simulated from satellite altimetry GMSL measurements using the 6th linear constant (

) of 1.1 mm/year. Given the interconnectedness of the world’s oceans through thermohaline circulation (the Global Ocean Conveyor or the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt) [

33], we apply the GMSLR linear constant (

) of 1.1 mm/year since 1900 and the acceleration (

) of 0.120 mm/year

2 (

in Equation (A2b)) since 1992 to RSLC simulation during 1900–2100 for understanding the difference in GSLC (

) from GMSLR (

) in CB in this paper.

3. Regional Sea-Level Trend and Acceleration

Figure A2A through A2O in

Appendix C shows the simulated RSLC equations of 15 TG stations based on Equations (A1a) and (A1b). Linear constant (

) values of RSLC simulated by using Equations (A1a), (A1b) and (A4) for the 15 TGs in this study are given in column (col.) 3 from row 3 to 17 in

Table 1. Row 3 and col. 4 in

Table 1 shows the

of 3.12 mm/year at TG Baltimore.

Supplementary Figure S3 indicates linear LS rate (

) of 1.86 mm/year (i.e.,

in Equations (A4)–(A6)) at the Baltimore TG, determined from the VLM rate data in [

4]. This value is also given in

Table 1, row 3, col. 12. By removing

of 1.86 mm/year from

of 3.12 mm/year, the linear constant (

in Equation (A5a)) of GSLC (

) is determined to be 1.26 mm/year (see Equation (A6) for this value). The linear constant of RSLR (i.e.,

in Equation (A5a)) can be determined to be 0.16 mm/year by subtracting

mm/year from

1.26 mm/year.

Supplementary Figure S4 presents the simulated GSLC (

) acceleration (

in Equation (A5b)) of 0.1016 and 0.0966 mm/year

2 from TG data at Baltimore and New York, respectively, with an average of 0.0991 mm/year

2. We adopt 0.0991 mm/year

2 as a uniform GSLC acceleration (

) along the northeastern coast of the United States from Virginia to New York, due to seasonal sea-level change similarity shown in Part 1 [

10], the acceleration of RSLR (

) for the coast can be found to be −0.021 mm/year

2 by subtracting

of 0.120 mm/year

2, which refers to the GMSL acceleration in

Section 2, from

of 0.0991 mm/year

2. One can calculate the RSLR

in CB using Equations (A3a) and (A3b).

Bedrock surface subsidence (BSS) contour map: VLM/LS derived from GPS height measurements [

34] and from interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) images [

3,

4] cannot be solely attributed to the GIA contribution to RSLC (

) if the measurement and image data are contaminated by non-GIA processes, which cause CS [

35]. The LS rate values (

, i.e.,

) given in

Table 1, col. 9, row 4 to 17 for the 14 TGs are solved by using Equation (A6) with

of 1.26 mm/year and

of 1.86 mm/year at the Baltimore TG and the linear correlation coefficient (

) values (shown in

Supplementary Figure S1 B2 through O2 in Part 1 [

10]). However, LS at the 11 TGs in

Table 1, col. 9, row 7 to 17 is contaminated by non-GIA processes with non-zero CS of 0.26 to 0.75 mm/year in

Table 1, col. 8, row 7 to 17. This is why we define BSS in

Figure 1 and

Supplementary Table S3 to simplify understanding of the global GIA contribution to RSLC in this paper. The BSS trend, characterized by a linear progression over time [

36,

37], is applied in our study. BSS contour lines in the CB area, ranging from 1.68 to 2.42 mm/year with an interval of 0.02 mm/year, are depicted in

Figure 1 (gray dashed lines). These are plotted by interpolating the simulated LS rates (

) in col. 9 from row 3 to row 6 in

Table 1 for four TG locations: Baltimore, Washington D.C., Ocean City, and Kiptopeke where CS is zero or insignificant. In the CB western shore area, the TG Baltimore is seated on the compressible Patuxent sand aquifer system (C

OC; see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2A), actively developed for groundwater extraction during 1850–1982 [

38]. The Patuxent aquifer system receives recharge from precipitation in its outcrop area. Historical data from a nearby groundwater well, 2S5E-1, show a low water level of approximately −30 m in the 1950s (

Supplementary Figure S2A), which is still higher than the regional pre-consolidation head of around −58 m (

Supplementary Figure S5), indicating recoverable temporal elastic compaction.

Supplementary Figure S2A displays three stable periods of groundwater levels (1946–1960, 1964–1980, and 1985–1998), with recovery to MSL and has remained stable since the 2000s, suggesting negligible PCS impact from 1900 to 2023. Therefore, LS

BSS = 1.86 mm/year at TG Baltimore (

Supplementary Figure S3). The TG Washington D.C. is situated on the pre-C stratum (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2B), with stable groundwater level since the 1950s (

Supplementary Figure S2B), indicating that LS

BSS at this location. Removal of

1.26 mm/year from the simulated RSLC linear constant (

) of 3.32 mm/year (

Table 1, col. 4, row 4) yields a BSS (

) of 2.06 mm/year (

Table 1, col. 7, row 4). In CB’s lower eastern shore area, near TG Ocean City, there exist 15 wells within the Ocean City aquifer (T

OC) at depths of 55 to 115 m, along with eight wells in the Manokin aquifer (T

OC) at depths of 103 to 160 m (

Supplementary Figure S6) [

39], with relatively small groundwater demand and adequate recharge from rainfall (

Supplementary Figure S2(C1,C2)). This implies LS

BSS. Removal of

1.26 mm/year from the simulated RSLC linear constant (

) of 3.18 mm/year (

Table 1, col. 4, row 5) yields the BSS of 1.92 mm/year (

Table 1, col. 7, row 5). In Virginia’s eastern shore peninsula, minimum groundwater development has occurred in the C

OC and T

OC aquifer systems around TG Kiptopeke located the inner rim of the CB Impact Crater (see location and geology in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2B), as evidenced by stable groundwater level in four wells at varying depths (

Figure S2 D1 through D4) and as simulated in three major aquifer systems [Potomac (C

OC in

Supplementary Figure S7A), Aquia (in

Figure S7B), and Piney Point (T

OC in

Figure S7C) aquifers] [

40]. Consequently, PCS is inferred to be zero, implying that LS

BSS. The simulated RSLC linear constant (

) from TG Kiptopeke data is 3.58 mm/year (

Table 1, col. 4, row 6), corresponding to a BSS (

) of 2.32 mm/year (

Table 1, col. 7, row 6). The general increase in BSS from north to south, as shown in

Figure 1, supports the conclusion of linear SLR increases from north to south in [

41].

Table 1.

Simulation results and comparisons of linear RSLC trends.

Table 1.

Simulation results and comparisons of linear RSLC trends.

| Information from NOAA | Linear Features of RSLC Trend in This STUDY

(mm/year) | LS Trend (mm/year) in Other Studies |

|---|

| Tide gauge | Data period

(yrs.) | RSLT a

(mm/year) | Linear constant b

() |

c | d | BSS g | CS h

PCS/CIS | LS

() | Leveling [25] |

GPS/d l | InSAR

[4] |

| Baltimore MD | 1902–2024

(122) | 3.27

0.12 | 3.12

0.03 | 2.02

0.30 | 0.16 e

0.43 | 1.86

0.31 | 0

0/0 | 1.86 i

0.31 | 1.790.38 | 1.790.52

UMBC m/12 | 1.86

0.31 |

| Washington DC | 1924–2024

(100) | 3.49

0.26 | 3.32

0.04 | 2.22

0.30 | 0.16 f

0.43 | 2.06

0.43 | 0

0/0 | 2.06 j

0.43 | 1.100.40 | n/a | n/a |

| Ocean City MD | 1975–2024 (49) | 5.15

0.69 | 3.18

0.19 | 2.08

0.30 | 1.92

0.43 | 0

0/0 | 1.92 j

0.43 | n/a | n/a | 4.23

2.70 |

| Kiptopeke VA | 1951–2024 (73) | 3.95

0.29 | 3.58

0.11 | 2.48

0.30 | 2.32

0.43 | 0

0/00 | 2.32 j

0.43 | 1.060.71 | n/a | n/a |

| Sewells Point VA | 1927–2024 (97) | 4.79

0.21 | 4.36

0.09 | 3.26

0.30 | 2.42

0.43 | 0.680.43

0.680.43/0 | 3.10 j

0.43 | 2.420.51

Hampton Roads k | 2.570.47

DRV6 n/21 | 2.20

0.51 |

| Yorktown VA | 1950–2024 (74) | 4.81

0.31 | 4.18

0.14 | 3.28

0.30 | 2.38

0.43 | 0.740.43

0.740.43/0 | 3.12 j

0.43 | 3.090.83 | 2.471.14

YRVA n/1.3 | 2.29

0.52 |

| Cambridge MD | 1943–2024 (81) | 3.97

0.29 | 3.60

0.10 | 2.50

0.30 | 1.98

0.43 | 0.360.43

0.360.43/0 | 2.34 j

0.43 | 1.930.0.65 | 2.340.10

NPT m /7 | 2.02

n/a |

| Solomons Island MD | 1937–2024 (87) | 4.04

0.23 | 3.85

0.09 | 2.75

0.30 | 2.10

0.43 | 0.490.43

0.490.43/0 | 2.59 j

0.43 | 2.450.48 | 2.400.30

SOL1 m/0.4 | n/a |

| Annapolis MD | 1928–2024 (96) | 3.80

0.19 | 3.49

0.04 | 2.39

0.30 | 1.92

0.43 | 0.310.43

0.310.43/0 | 2.23 j

0.43 | 2.100.38 | 2.240.17

LOYF m /5 | 2.15

0.20 |

| Lewisetta VA | 1970–2024 (54) | 5.87

0.54 | 4.20

0.18 | 3.10

0.30 | 2.19

0.43 | 0.750.43

0.750.43/0 | 2.94 j

0.43 | 3.060.95

Saluda k | n/a | 0.52

1.11 |

| Dahlgren VA | 1972–2024 (52) | 5.63

0.59 | 4.10

0.17 | 3.00

0.30 | 2.22

0.43 | 0.620.43

0.620.43/0 | 2.84 j

0.43 | 1.970.60

Allens Fresh k | n/a | n/a |

| Tolchester Beach, MD | 1971–2024 (53) | 4.10

0.84 | 3.59

0.23 | 2.71

0.30 | 1.83

0.43 | 0.500.43

0.720.43/0 | 2.55 j

0.43 | 3.030.43

Chestertown k | n/a | 0.66

1.87 |

| Chesapeake City MD | 1972–2024 (52) | 4.35

0.60 | 3.20

0.11 | 2.10

0.30 | 1.68

0.43 | 0.260.43

0.260.43/0 | 1.94 j

0.43 | 2.320.49 | n/a | 3.10

1.12 |

| Wachapreague, VA | 1978–2024 (46) | 5.63

0.59 | 3.69

0.16 | 2.59

0.30 | 2.17

0.43 | 0.260.43

0.260.43/0 | 2.43 j

0.43 | n/a | n/a | 3.31

1.52 |

| CBBT VA | 1975–2024 (49) | 6.14

0.56 | 4.14

0.18 | 3.04

0.30 | 2.36

0.43 | 0.520.43

0/0.520.43 | 2.88 j

0.43 | 2.770.52

Norfolk k | n/a | 2.38

1.08 |

| Average | (72) | 4.60

0.42 | 3.72

0.12 | 2.64

0.30 | 2.17

0.43 | 0.380.43

0.380.43/na | 2.47

0.43 | 2.24

0.58 | 2.29

0.45 | 2.25

1.09 |

4. Compaction Subsidence (CS)

The over-consolidated Tertiary (T

OC) and Cretaceous (C

OC) aquifer systems in the Southern CB region have experienced compaction at rates of 1.5 to 3.7 mm/year due to extensive groundwater pumping [

43]. Groundwater from the confined aquifers (T

OC and C

OC) of the Maryland coastal plain has been withdrawn for decades as the primary source of water supply [

44]. LS in the Maryland coastal plain has been monitored at rates ranging from 0.1 to 7.1 mm/year [

44]. However, little investigation has been conducted on CIS at the TG locations in the study area. To better understand the impacts of these two non-GIA processes on RSLC, we quantify the CS of the 0 to 2230 m-thick sediments (Quaternary (

Q), T

OC and C

OC) above the bedrock surface at the 15 TG locations in the CB area in terms of PCS and CIS. CS in col. 8 of

Table 1 at each TG location is calculated as the difference between LS in col. 9 and BSS in col. 7. BSS at the 11 TG locations, excluding Baltimore, Washington DC, Ocean City, and Kiptopeke, and is determined from the BSS contour lines in

Figure 1. CS at the 15 TG locations ranges 0.00 at Baltimore, Washington DC, Ocean City, and Kiptopeke to 0.75 mm/year at Lewisetta, VA in the Southern CB region.

Estimated primary consolidation subsidence (PCS): Estimated PCS rates of the last 14 TGs are shown in col. 8 of

Table 1, excluding TG CBBT where the compaction of aquifer systems is attributed to CIS. According to our approach, PCS values at the 10 TG locations range from 0.26 mm/year at TG Wachapreague, VA, to 0.75 mm/year at TG Lewisetta, VA. The average PCS is 0.38 mm/year during 1900 to 2023. The proportion of PCS relative to the total LS rate at top five locations are as follows: 26% at TG Lewisetta, VA; 24% at Yorktown, VA; 22% at Sewells Point, VA, and Dahlgren, VA; and 20% at TG Tolchester Beach, MD, respectively.

Construction-induced subsidence (CIS) of 0.52 mm/year during 1960–1990 at CBBT VA: In the literature, the CIS detected by synthetic aperture radar (SAR) data at underground tunnels in five cities at Korea exceeds 40 mm/year, with a maximum cumulative subsidence of ~200 mm [

45]. CBBT is a remarkable engineering project started in 1958 [

46]. In the context of construction projects undertaken in complex and challenging geo-environments, various factors can contribute to LS both during construction and post-construction. These factors may include the excavation of soil and the construction of retaining walls and temporary docks, as well as the deployment of large rocks for protection, etc., as introduced in [

47]. The geological cross-sections depicted in

Figure 2 illustrate that the TG CBBT is situated on the unconsolidated Q strata, making it more susceptible to impacts from construction. The TG is about 300 m away from the ‘Island Three’ construction site (

Figure S8) and located in the CB Impact Crater (

Figure 1). However, time series of MMSL (monthly mean sea level) at TG CBBT show a relatively larger variation before 2000 compared to nearby TGs Kiptopeke and Sewells Points (

Supplementary Figure S9). A piecewise method has been applied to investigating the RSLC trend at CBBT (see equations in

Figure A2O). In the extended timeframe from 1900 to 2100, the period spanning from 1960 to 1990 is likely to have been directly influenced by construction activities. A CIS ([col. 8, row 17] of

Table 1) is calculated to be 0.52 mm/year. This is especially relevant for TG CBBT, situated within the CB bolide impact crater—a region noted for minimal aquifer drawdown (

Figure S7). After the 1990s, post-construction observations gradually aligned with results from Kiptopeke (

Figure S9), affirming the consistency and validity of our granular analysis approach across the 15 TGs in the CB region. Thus, TG CBBT recorded an average CIS of 0.52 mm/year during the 1960s to 1990s, while its PCS value has been zero since 1900.

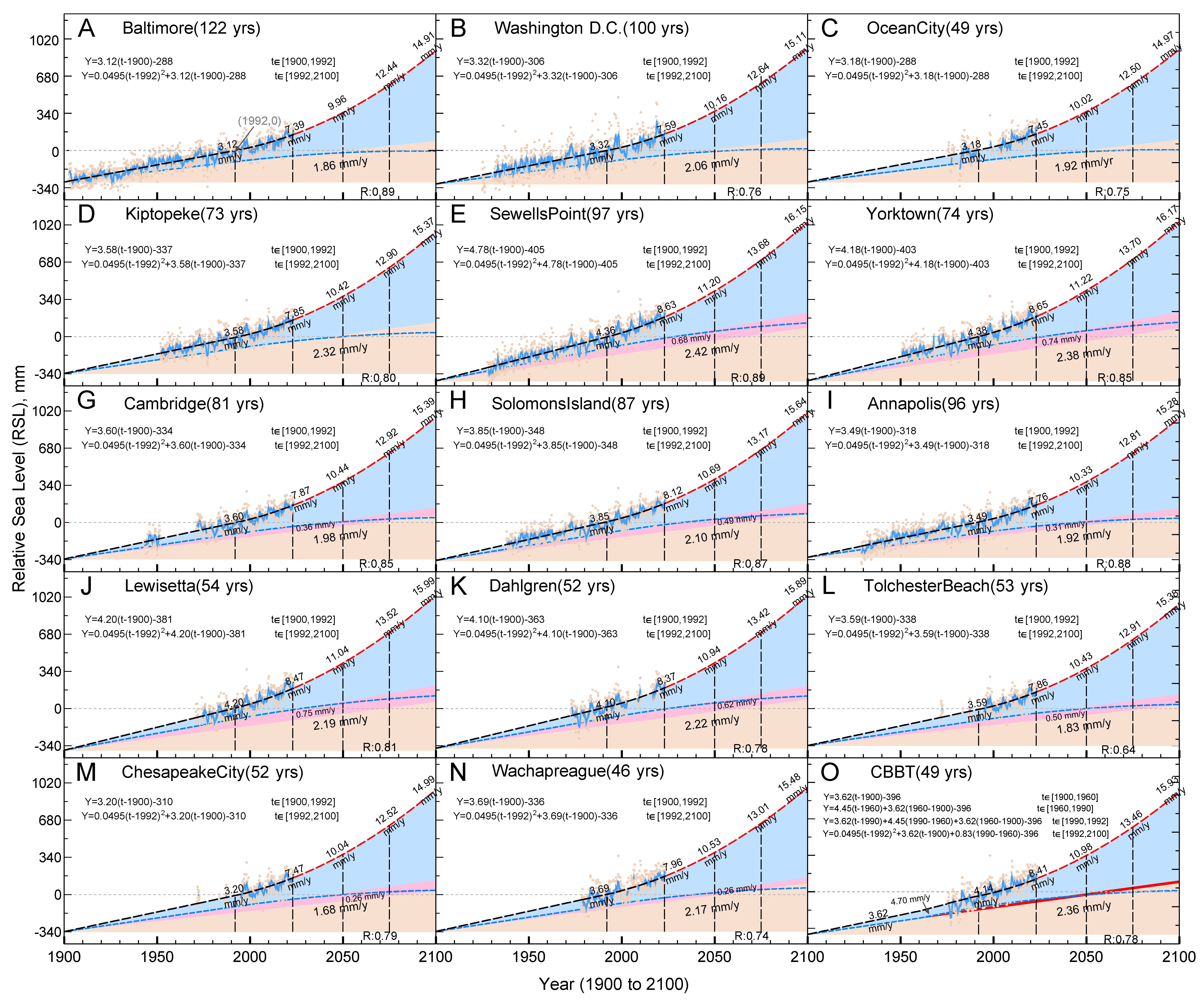

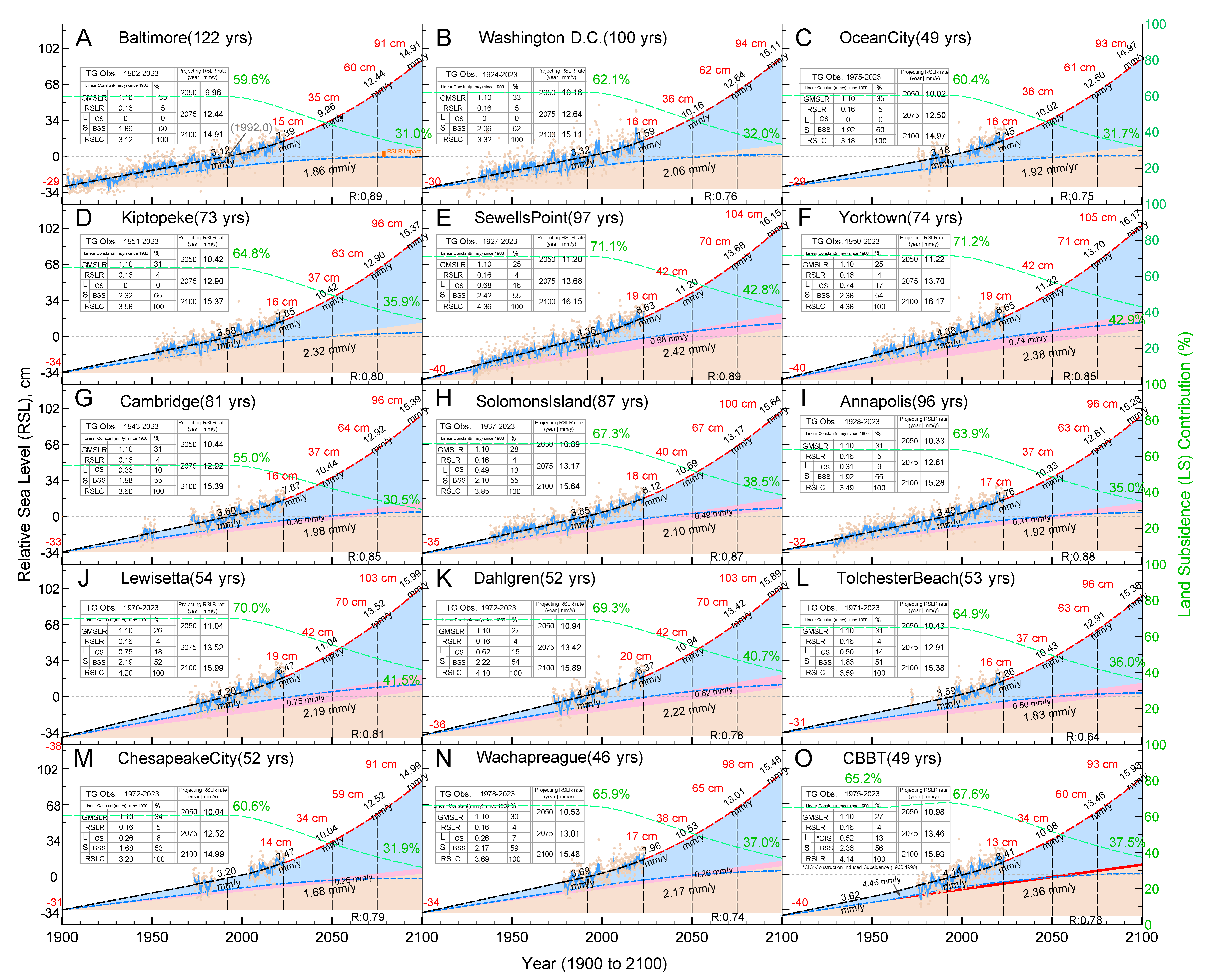

5. Simulated Relative Sea-Level Trends in the 20th Century and Projections for 21st Century

RSLC along the CB coast from 1900 to 2100 is projected to range between 120 cm at Baltimore and 145 cm at Yorktown. The LS contribution to this rise was 55–71% during 1900–1992, but it is expected to decrease to 31–43% by 2100 (see green color numbers in

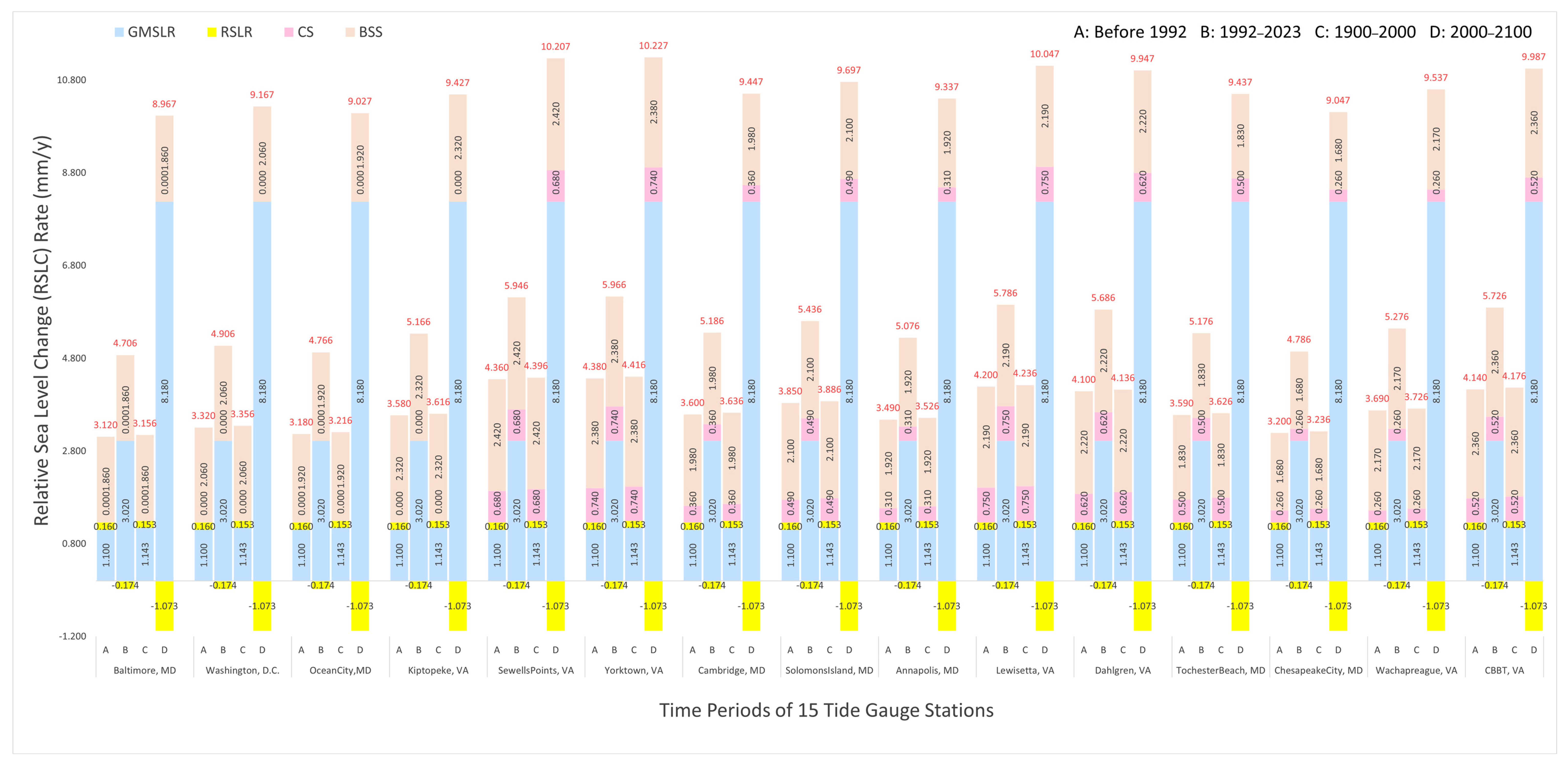

Figure 4). The detailed breakdown of factors contributing to the average RSLC rate is displayed in

Figure A2. Components of GSLC (=GMSLR + RSLR), CS, and BSS are represented in blue, magenta, and brown, respectively. We also display average RSLC rates in different periods, which correspond to cols. A, B, C, and D in

Figure 5.

1900–1992: RSLC is 29–40 cm (

Figure 4) during this period, while the LS contribution remains a consistent percentage (except TG CBBT) ranging from 55 to 71.2% (green dash lines in

Figure 4). The average RSLC rate ranges from 3.12 mm/year at Baltimore, MD, to 4.38 mm/year at Yorktown, VA (see locations in

Figure 1, curves in

Figure 4A,F, and magnitudes from cols. A in

Figure 5), with an average of 3.72 mm/year (see [col. 4, row 18] in

Table 1) over the 92 years in the 20th century. The period of 1900–1992 is a linear increase period of RSLC since both LS and GSLC are assumed to follow a linear trend (

Figure 4).

1992–2023: RSLC is 15–20 cm while the LS decreases to 49.7–65.5% by 2023 (

Figure 4). The average RSLC rates range from 4.71 mm/year at Baltimore, MD, to 5.97 mm/year at Yorktown, VA (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 4A,F, and cols. B in

Figure 5). The average RSLC rate of the 15 TGs is 5.31 mm/year. A critical observation is that the GMSLR rate of 3.02 mm/year, which is comparable to the recognized GMSL rate of ∼3 ± 0.4 mm/year estimated by satellite altimetry since 1993 [

20], positions it as the primary contributor.

1900–2000: RSLC is 32–44 cm while the contribution of LS is 55.0–71.2% from 1900 to 1992, after which it begins to decrease to 54.5–70.7% by 2000 (

Figure 4). The average RSLC rates across the 20th century ranged from 3.16 mm/year in Baltimore, MD, to 4.42 mm/year in Yorktown, VA, averaging 3.76 mm/year. The average GMSLR rate is 1.14 mm/year (cols. C of

Figure 5), marginally exceeding the GMSLR linear rate of 1.10 mm/year, primarily due to the 8 yrs accelerated GSLC at the onset of the climate change era.

2000–2100: The RSLC is projected to be 53–99 cm from 2000 to 2100 (red fonts in

Figure 4), while the LS contribution is expected to decrease to less than 50% after the 2040s and will gradually reduce to 30–40% by 2100 (

Figure 4). The projected average RSLC rates are in the range of 9.96–11.22 mm/year in 2050, 12.44–13.70 mm/year in 2075, and 14.91–16.17 mm/year in 2100 (see labels along the curve in

Figure 4). The average GSLC rate of 8.18 mm/year marks a substantial increase, being almost 7.4 times of 1.10 mm/year, which is projected to contribute 60–70% by 2100 (cols. D of

Figure 5). The RSLC rate was projected from 2000 to 2100, ranging from 8.97 mm/year at Baltimore, MD, to 10.23 mm/year at Yorktown, VA, with an average rate of 9.57 mm/year during the 21st century.

6. Discussion

Baseline of relative sea level (RSL): National Tidal Datum Epoch (NTDE) is a 19-year period established by the National Ocean Service (NOS) for collecting water level observations and calculating tidal datum values. The NOAA follows a policy of revising the NTDE every 20–25 years to account for changes in RSL due to global sea level, long-term regional oceanographic and meteorological variations, and VLMs. The midpoint year of the current NTDE, spanning from 1983 to 2001, is 1992. Thus, the TG data obtained from the NOAA are generally based on a 1992 baseline. Data from the 14 TGs (except TG CBBT) acquired from the NOAA indicate a value of 0 at the epoch of 1992.0. While we do not use the information (1992, 0) to process the simulation, 14 subplots come across around the point of (1992, 0) coincidentally (see gray horizontal dotted lines in

Figure 4). This outcome mathematically validates our analysis and deconstruction of the NOAA RSLC time series data.

Uncertainty of Relative Sea-Level Trend and RSLC: Various sources of uncertainty play a significant role in affecting the convergence of data obtained from measured tide gauges (TGs). These include measurement errors in TGs [

48], the geographical location of TGs, the influence of surface currents and deep ocean currents (such as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current), the tide change periodicity [

49,

50], variability in storm surges [

51], the complexity of SLR on a global and regional scale due to climate change, and the non-linearity of VLM related to geological and anthropogenic factors. Additionally, data gaps further contribute to the uncertainty, especially for about-five-decade short-term TGs. The uncertainty of the NOAA RSL trends (RSLTs) range from

0.12 mm/year for a 12-decade record at Baltimore to

0.54 ~

0.84 mm/year for about-five-decade records at seven TGs—Ocean City, Lewisetta, Dahlgren, Tolchester Beach, Chesapeake City, Wachapreague, and CBBT—with an average of

0.42 mm/year (see col. 3 in

Table 1). Mathematically, these values generally adhere to a linear rate throughout the corresponding data period. However, our method simulates the time series data by analyzing RSLC trends as a compound one, incorporating a linear rate dating back to 1900 and a quadratic acceleration rate beginning in 1992, with guidance of the longest time series of RSLC at Baltimore to extract the trend from the 11-month moving average dataset. The statistical summary, including the correlation coefficient (R), is displayed at the bottom right of the subplot at each TG in

Figure 4. Treating seasonal monthly average water-level change patterns at the 15 TGs as regionally similar and using Baltimore as the reference tide station (see Part 1 [

10]), the uncertainty of our RSLC trends ranges from

0.03 mm/year for a 12-decade record at Baltimore to

0.11 ~

0.23 mm/year for about-five-decade records at seven TGs—Ocean City, Lewisetta, Dahlgren, Tolchester Beach, Chesapeake City, Wachapreague, and CBBT—with an average of

0.12 mm/year (see col. 4 in

Table 1).

Quadratic acceleration of 0.120 ± 0.025 mm/year

2 for GMSLR and 0.099 ± 0.013 mm/year

2 for GSLC: Nerem et al. [

20] estimated the climate change-driven acceleration of GMSL over the 25 years from 1992 to 2017 to be 0.084 ± 0.025 mm/year

2 using a 25-year time series of precision satellite altimeter data from TOPEX/Poseidon, Jason-1, Jason-2, and Jason-3. GMSL acceleration of 0.084 mm/year

2 can also be derived from satellite altimeter data in

Figure 3 if the GMSL linear rate of 1.70 mm/year [

29] is applied. This implies that derivation of GMSL quadratic acceleration depends on appropriate magnitude of the GMSL linear constant. The GMSL quadratic acceleration of 0.120 ± 0.025 mm/year

2 in this paper is established on the state-of-the-art assessment of the sixth GMSL linear constant of 1.1 mm/year [

32]. The uncertainty of ±0.025 mm/year

2 is taken as the sum of satellite instrument drift error of ±0.011 mm/year and decadal variability of ±0.014 mm from [

20], rather than ± 0.0019 mm/year

2 from the correlation in

Figure 3. The GMSL in the current trend, with an acceleration of 0.120 mm/year

2 since 1992 and a linear constant of 1.10 mm/year since 1900, will be 79 cm by 2100. This projection falls within 63–101 cm of the likely GMSLR relative to 1995–2014 under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) 5–8.5 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions scenario projected by IPCC [

13]. This trend leads to a GMSLR of 81 cm in the 21st century, which is 7.4 times that of the 11 cm observed in the 20th century. However, the error of ±0.013 mm/year

2, which is very similar to the above decadal variability of ±0.014 mm/year

2 [

20] for the 12-decade long-term TG-data derived GSLC acceleration of 0.099 mm/year

2, is obtained from the correlation of Equations (A1a) and (A1b) without instrument drift and is only 50% of the GMSLR error. The GSLC acceleration of 0.099 mm/year

2 is lower than the satellite-based GMSLR by 0.021 mm/year

2. This may reflect the effect of significant coastal sedimentation [

52]; increasing coastal sediment volume reduces basin capacity, thereby inflating the satellite-measured GMSL. Sea-level acceleration rates, ranging from 0.012 to 0.16 mm/year

2 between 1978 and 2021, increase from south to north [

41] under the assumption of spatially varied acceleration since 1978.

Linear constant of 0.16 ± 0.43 mm/year and quadratic acceleration of −0.021 ± 0.013 mm/year

2 for RSLR: The error of ±0.43 mm/year for the linear constant of 0.16 mm/year of RSLR in the CB area arises from both large independent errors of ±0.31 mm/year for the Baltimore LS rate of 1.86 mm/year derived from InSAR data [

4] and ±0.30 mm/year for the linear constant of 1.1 mm/year of GMSLR derived from global TG data [

32]. Therefore, the linear constant of RSLR in the CB area may vary from −0.45 to 0.77 mm/year. However, a negative linear constant of RSLR is unlikely for a seafloor sinking coastal area like the CB region. A 0.77 mm/year linear constant of RSLR implies an LS rate of 1.25 mm/year at Baltimore, which is not supported by different VLM measurements in this region. The 0.16 mm/year RSLR was primarily driven by regional oceanic processes such as changes in circulation, density variations (temperature and salinity), and global gravitational, rotational, and deformational (GRD) effects during 1900–1992. The quadratic acceleration of RSLR varies from −0.034 to −0.008 mm/year

2, indicating a negative.

Figure 5 shows an average RSLR rate of 0.15 mm/year in the 20th century (see cols. C) will be reduced to −1.07 mm/year in the 21st century (see

Figure 5 Cols. D) by the negative RSLR acceleration. This suggests that negative RSLR acceleration may significantly capture the ongoing shrinkage of coastal seawater storage space [

53], while also reflecting a rapid increase in global seawater volume since 1992.

Comparison of identified LS rates:

Table 1 compares the LS rates identified by this study with historical leveling observations from 1970s, relevant GPS records, and InSAR results from recent decades. Holdahl and Morrison (1974) [

25] estimated LS rates of 1.06 ± 0.38 to 3.09 ± 0.95 mm/year, with an average of 2.24 ± 0.58 mm/year at eight TGs and six nearby TGs (col. 10) over a period of 20 to 31 years (1940 to 1971) by removing the 1st GMSLR linear constant of 1.00 mm/year [

25]. There are five paired reference GPS stations (col. 11) near the corresponding TGs in this study (see locations of ‘Other GPS’ in

Figure 1). These TGs include Baltimore, Sewells Point, Yorktown, Cambridge, Solomons Island, and Annapolis. The GPS results (rows 7–11 of col. 11) indicate LS rates of 1.70 ± 0.10 to 2.57 ± 1.14 mm/year (col. 11), with an average of 2.29 ± 0.45 mm/year. For instance, GPS DRV6, located about 21 km away from TG Sewells Point, shows a LS rate of 2.57 ± 0.47 mm/year over the 19 years of observations from 2002 to 2020, which is comparable to 3.10 ± mm/year ([col. 9, row 7]). InSAR data-derived LS rates near 11 TGs range from 0.52 ± 0.20 to 4.23 ± 2.70 mm/year, with an average of 2.25 ±1.09 mm/year. These values, reported by Ohenhen and Barnard (2024) [

4], are listed in col. 12. Our study shows TG data-derived LS rates of 1.92 ± 0.43 to 3.12 ± 0.43 mm/year, with an average of 2.52 ±0.43 mm/year at 14 TGs (rows 4 to 17 of col. 9) using the InSAR data-derived LS of 1.86 ± 0.31 mm/year near TG Baltimore [

4].

Application of BSS to find PCS from other LS measurements: The LS results from our study (shown in red in

Figure S11) are compared with other sources: historical leveling contours until the 1970s (in black) [

25], GPS observations by the Maryland Geological Survey (MGS) (in green) [

44], and borehole extensometer measurements by USGS, VA (in blue) [

54] in the CB area. Our study’s LS trend since 1900 reflects an average effect. For instance, we estimate the LS rate at Annapolis to be 2.23 mm/year, which combines 1.92 mm/year BSS and 0.31 mm/year PCS (

CS). The 1.92 mm/year BSS aligns closely with the leveling result of 2.10 ± 0.38 mm/year, while the three MGS GPS readings of 2.5 mm/year, 2.7 mm/year, and 3.4 mm/year (see locations of CROF, BROA, and ARNO in

Figure S12, and magnitude in

Table S5) near TG Annapolis indicate a growing PCS in the recent two decades. Similarly, The LS rate at Solomons Island is 2.59 mm/year, with 2.10 mm/year BSS and 0.49 mm/year PCS. The inferred LS of 2.59 ± 0.43 mm/year is comparable to GPS observations, which indicate a rate of 2.7 mm/year (see COV1 in

Figure S12 and

Table S5). Four borehole extensometers record aquifer-system thickness changes across the Virginia Coastal Plain in Franklin, Suffolk, Nansemond, and West Point [

54]. LS rates of 1.5 mm/year in Franklin and 3.7 mm/year in Suffolk are recorded. A cumulative compaction of −0.14 mm is observed in the Nansemond extensometer (see

Figure S13), which monitors managed aquifer recharge for the Potomac aquifer system under the SWIFT (Sustainable Water Initiate for Tomorrow) project by the HRSD (Hampton Roads Sanitation District). Records from West Point (scheduled to be completed in 2025) are not yet available. Borehole extensometers are crucial for identifying LS causes due to groundwater withdrawal. Further analyses will be conducted as more data from extensometers, GPS, and groundwater studies become available.

Several locations exhibit abnormally high PCS. Projections in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 indicate TG Lewisetta will have the highest RSLC trend by 2100, attributed to large BSS (2.19 mm/year) and PCS (0.75 mm/year). Areas near TGs Sewells Point ([2.42, 0.68] mm/year, Yorktown ([2.38, 0.74] mm/year), Dahlgren ([2.22, 0.62] mm/year), Cambridge ([1.98, 0.36] mm/year), and Solomons Island ([2.10, 0.49] mm/year), along with TG Lewisetta, are identified as high RSLC risk areas. The MGS report [

44] investigated LS induced by groundwater withdrawal from Coastal Plain Aquifers.

Table S6 summarizes the deepest water-level altitude in five main aquifers, while

Figure S14 identifies three locations situated at the cone of depression in composite water levels, mainly due to excessive groundwater withdrawal. If high groundwater demand remains poorly regulated, the CS rate is expected to continue increasing, which will directly worsen the LS rate. The MGS GPS survey found the LS in Waldorf to be 7.1 mm/year (corresponding to GPS WAL1, see

Figure S12 and

Table S5). Subtracting the BSS near Waldorf (approximately 2.12 mm/year inferred from

Figure 1) from 7.1 mm/year gives an estimated PCS of about 4.98 mm/year. Similar situations are noted at the two GPS stations in Dorchester, MD (

Figure S12), where the BSS near GPS PTNK and MSTP is 2.03 and 2.04 mm/year, respectively (

Figure 1), resulting in PCS rates of 4.47 mm/year and 10.46 mm/year, respectively. Thus, four abnormally high PCS locations near Cambridge, Solomons Island, Waldorf, and Dorchester County in MD in

Figure S11 are identified and warrant public attention due to the dramatic increase in PCS. For coastal communities, the urgent implementation of resilience strategies is crucial.

7. Conclusions

We applied a comprehensive methodology for deciphering relative sea-level change (RSLC)—which integrates global mean sea-level rise (GMSLR), regional sea-level rise (RSLR), and land subsidence (LS) as proposed in Part 1 [

10]—to Chesapeake Bay in Part 2. Our key conclusions are as follows:

Global Mean Sea-Level Trends: Of six historical assessments since the 1970s, Dangendorf et al. (2017) [

32] suggest a best-estimate linear GMSLR trend of 1.1 ± 0.30 mm/year since 1900. Since 1992, satellite altimetry indicates accelerating GMSL at 0.120 ± 0.025 mm/year

2.

RSLC and LS at Tide Gauges: Analysis of over 122 years of tide gauge data from Baltimore and New York reveals that relative sea level has accelerated at 0.099 ± 0.013 mm/year

2 since 1992. At Baltimore, the linear RSLC trend since 1900 is simulated at 2.02 ± 0.03 mm/year. Meanwhile, the LS at the Baltimore tide gauge is estimated at 1.86 ± 0.31 mm/year, based on vertical land motion derived from InSAR data [

3,

4].

Derivation of GSLC and RSLR: By subtracting the LS rate (1.86 ± 0.31 mm/year) from the simulated RSLC rate (2.02 ± 0.03 mm/year) at Baltimore, we derive a linear GSLC rate for the Chesapeake Bay of 1.26 ± 0.30 mm/year. This GSLC rate implies a linear RSLR deviation of 0.16 mm relative to the global average of 1.1 mm/year reported in [

32]. In contrast, the RSLR acceleration is estimated at –0.021 ± 0.025 mm/year

2—obtained by subtracting the global acceleration (0.120 ± 0.025 mm/year

2) from the regional acceleration (0.099 ± 0.013 mm/year

2). This negative acceleration likely reflects the ongoing shrinkage of coastal seawater storage space [

53] as well as a rapid increase in global seawater volume since 1992.

Spatial Variability of LS and Subsidence Components: Using Equation (A6) with the GSLC rate (1.26 ± 0.30 mm/year) and the Baltimore LS rate (1.86 ± 0.31 mm/year), LS at 14 short-term tide gauge locations ranges from 1.92 ± 0.43 mm/year at Ocean City, MD to 3.12 ± 0.43 mm/year at Yorktown, VA. Bedrock-surface subsidence (BSS) contour lines, mapped using data from tide gauges in Baltimore and Ocean City (MD), Washington, D.C., and Kiptopeke (VA), vary from 1.68 to 2.42 mm/year—where compaction subsidence (CS) of Quaternary, Tertiary, and Cretaceous sediments is negligible. By subtracting BSS from LS, CS at 15 tide gauge locations ranges from 0.00 mm/year at Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Ocean City, and Kiptopeke to 0.75 mm/year at Lewisetta, VA. Primary consolidation subsidence (PCS) due to groundwater withdrawal at 10 tide gauge locations ranges from 0.26 mm/year at TG Wachapreague, VA to 0.75 mm/year at TG Lewisetta, VA, with an average of 0.38 mm/year over the period 1900–2023. At the top five tide gauge locations, PCS constitutes 26% at TG Lewisetta, VA; 24% at Yorktown, VA; 22% at both Sewells Point and Dahlgren, VA; and 20% at TG Tolchester Beach, MD. Additionally, an average construction-induced subsidence (CIS) of 0.52 mm/year was inferred from tide gauge data at the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel (CBBT) in Virginia during the 1960s–1990s, while its PCS value remains zero since 1900.

Historical and Future RSLC: In the 20th century, the RSLC observed in Chesapeake Bay ranged from 32 to 44 cm. Projections based on the GMSLR, RSLR, and LS findings suggest that RSLC could range from 53 to 99 cm by 2100—with a clear increase from north to south along the bay. Before 1992, LS accounted for 55–71% of RSLC, primarily driven by glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) or tectonic processes and sediment compaction. At key tide gauge locations, LS rates vary from 1.68 to 2.42 mm/year in areas with minimal compaction (e.g., Baltimore and Washington, D.C.) to over 3 mm/year at stations with significant compaction (e.g., Lewisetta and Sewells Point). Furthermore, areas with marked compaction—particularly in the southern Chesapeake Bay—exhibit higher LS rates, exacerbating RSLC relative to the northern region. By 2100, GMSLR is expected to become the dominant driver of RSLC, accounting for 60–70% of the total rise, as its acceleration reaches 0.120 ± 0.025 mm/year2. The projected average RSLC rate for 2000–2100 is expected to exceed 9.5 mm/year, with the contribution from GMSLR nearly 7.4 times greater than that observed in the 20th century.

This comprehensive assessment enhances our understanding of the interplay between global, regional, and local factors driving sea-level change in the Chesapeake Bay region. Despite the potential lack of sufficient nearby groundwater level data to substantiate every case of severe LS, it is imperative to enact measures to halt PCS progression and mitigate frequent flooding. Failure to address these issues promptly will lead to a rapid increase in RSLC, impacting coastal communities and infrastructure, including roads, bridges, subways, and water supplies. A NASA Report in 2010 [

55] stated: “January 2000 to December 2009 was the warmest decade on record.” A NOAA Report in 2024 [

56] stated that “the 10 warmest years in the historical record have all occurred in the past decade (2014–2023)” and “2023 was the warmest year since global records began in 1850 by a wide margin.” Will meteorologists continue to announce new global warming records in the 2030s? Although we have not yet found all the answers, our approach underscores the critical need for local governments to acknowledge the urgency of these challenges. Proactive measures are essential to mitigate the impact of nuisance floods and safeguard critical infrastructure.