Effectiveness of Health Education Intervention on Water Sanitation and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria: A Cluster Randomised Control Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedure of the Study

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.4. Intervention Strategy

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. WASH Practice of Respondents at Baseline

3.2. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Health Education Intervention on WASH Practice

3.2.1. Comparing Changes from Baseline to Follow Between Intervention and Control Group

3.2.2. Factors Associated with WASH Practice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cumming, O.; Cairncross, S. Can water, sanitation and hygiene help eliminate stunting? Current evidence and policy implications. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Guide on Menstrual Health and Hygiene. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/wash/files/UNICEF-Guidance-menstrual-health-hygiene-2019.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Nigeria. Evaluation of the UNICEF Supported Federal Government of Nigeria Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programme (2014–2017). Available online: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/media/2986/file/Evaluation%20Report%20on%20WASH%20Programme%202014%20-%202017.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/media/10381/file/WATER,%20SANITATION%20AND%20HYGIENE%20IN%20SCHOOLS.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- World Health Organization. Improving Nutrition Outcomes with Better Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: Practical Solutions for Policies and Programmes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Protocol on Water and Health and the 2030 Agenda: A Practical Guide for Joint Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asha, A.C.; Karim, N.B.; Bakhtiar, M.; Rahaman, K.S. Adolescent athlete’s knowledge, attitude and practices about menstrual hygiene management (MHM) in BKSP, Bangladesh. Asian J. Med. Biol. Res. 2019, 5, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking Water; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). WASH as a Cornerstone for Conquering the 2017 Cholera Outbreak in Borno State, Northeast Nigeria; UNICEF Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Programme Division 3 United Nations Plaza: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dangour, A.D.; Watson, L.; Cumming, O.; Boisson, S.; Che, Y.; Velleman, Y.; Cavill, S.; Allen, E.; Uauy, R. Interventions to improve water quality and supply, sanitation and hygiene practices, and their effects on the nutritional status of children (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Sethi, V.; Nagargoje, V.P.; Saraswat, A.; Surani, N.; Agarwal, N.; Bhatia, V.; Ruikar, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Parhi, R.N.; et al. WASH practices and its association with nutritional status of adolescent girls in poverty pockets of eastern India. BMC Womens Health 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaei, G.; Andrews, K.G.; Sudfeld, C.R.; Mccoy, C.; Peet, E.; Sania, A.; Fawzi, M.C.S.; Ezzati, M.; Fawzi, W.W. Risk Factors for Childhood Stunting in 137 Developing Countries: A Comparative Risk Assessment Analysis at Global, Regional, and Country Levels. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.E.; Fahmy, H.H.; Mohamed, S.E.; El Hawy, L.L. Effect of health education about healthy diet, physical activity and personal hygiene among governmental primary school children (11-13 years old) in Sharkia Governorate-Egypt. J. Am. Sci. 2016, 12, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tofail, F.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Das, K.K.; Rahman, M.; Ahmed, T.; Jannat, K.K.; Unicomb, L.; Arnold, B.F.; Ashraf, S.; Winch, P.J.; et al. Effect of water quality, sanitation, hand washing, and nutritional interventions on child development in rural Bangladesh (WASH Benefits Bangladesh): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.E.; Rahman, M.; Itsuko, K.; Mutahara, M.; Sakisaka, K. The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: An intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Women’s Health Coalition (IWHC). Integrating Sexual and Reproductive Health in Wash. Available online: https://iwhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/SRHR-WASH-Fact-Sheet_WebFinal.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Borno, State in Nigeria. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/php/nigeria-admin.php?adm1id=NGA008 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- NPC National Population Commission (2006). Available online: http://www.population.gov.ng/index.php/publication/140-popn-distri-by-sex-state-jgas-and-senatorial-distr-2006 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- National Bureau of Statistics (Nigeria). Annual Abstract of Statistics, 2012. National Bureau of Statistics Federal Rebublic of Nigeria [Online]. 2012 May 9. 1-619. Available online: https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/pdfuploads/annual_abstract_2012.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Lemeshow, S.; Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Klar, J.; Lwanga, S.K. Adequacy of Sample Size in Health Studies; Wiley: Chichester, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 0-471-92517-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Stewart, D.; Chang, C.; Shi, Y. Effect of a school-based nutrition education program on adolescents’ nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes and behaviour in rural areas of China. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2015, 20, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marías, Y.F.; Glasauer, P. Guidelines for Assessing Nutrition-Related Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–188. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3545e/i3545e.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED089343 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Fuad, R.A.; Arip, M.A.S.M.; Saad, F. Validity and Reliability of the HM-Learning Module among High School Students in Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kob, C.G.C.; Rakib, M.K.B.; Shah, A.; Arasinah. Development and Validity of TIG Welding Training Modules Based on the Dick and Raiser Model Design in the Subject (DJJ3032) of Mechanical Workshop Practice 3 in Polytechnic Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, W.; Tuckman Mohammed, A. Waheed Evaluating an individualized science program for community college students. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1981, 18, 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Duijster, D.; Monse, B.; Dimaisip-Nabuab, J.; Djuharnoko, P.; Heinrich-Weltzien, R.; Hobdell, M.; Kromeyer-Hauschild, K.; Kunthearith, Y.; Mijares-majini, M.C.; Siegmund, N. Fit for school’—A school-based water, sanitation and hygiene programme to improve child health: Results from a longitudinal study in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, C.L.F.; Rudan, I.; Liu, L.; Nair, H.; Theodoratou, E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; O’Brien, K.L.; Campbell, H.; Black, R.E. Global Burden of Childhood Pneumonia and Diarrhoea. Lancet 2013, 1405, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDI World Dental Federation. The Challenge of Oral Disease—A Call for Global Action. The Oral Health Atlas, 2nd ed.; Myriad Editions: Brighton, UK, 2015; Available online: www.myriadeditions.com (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Jackson, S.L.; Vann, W.F., Jr.; Kotch, J.B.; Pahel, B.T.; Lee, J.Y. Impact of Poor Oral Health on Children’s School Attendance and Performance. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1900–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Murali, R.; Shamala, A.; Yalamalli, M.; Kumar, A. Effectiveness of two oral health education intervention strategies among 12-year-old school children in North Bengaluru: A field trial. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2016, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midzi, N.; Mtapuri, S.; Mutsaka, M.J.; Ruhanya, V.; Magwenzi, M.; Chin, N.; Nyandoro, G.; Marume, A.; Kumar, N.; Mduluza, T. Impact of School Based Health Education on Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Grade Three Primary School Children in Zimbabwe. J. Community Med. Health Educ. 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.C.; Clasen, T.; Dreibelbis, R.; Saboori, S. The impact of a school-based water supply and treatment, hygiene, and sanitation programme on pupil diarrhoea: A cluster-randomized trial. Epidemiol. Infect 2014, 142, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijster, D.; Buxton, H.; Benzian, H.; Bella, J.D.; Volgenant, C.; Dreibelbis, R.; Buxton, H.; Dimaisip-nabuab, J. Impact of a school-based water, sanitation and hygiene programme on children’s independent handwashing and toothbrushing habits: A cluster-randomised trial. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1699–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Schindler, C.; Odermatt, P.; Gerold, J.; Erismann, S.; Sharma, S.; Koju, R.; Utzinger, J.; Cissé, G. Nutritional and health status of children 15 months after integrated school garden, nutrition, and water, sanitation and hygiene interventions: A cluster-randomised controlled trial in Nepal. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapu, R.C.; Ismail, S.; Ahmad, N.; Lim, P.Y.; Njodi, I.A. Food Security and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria. Foods 2020, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, M.A. Evaluating the Relationship Between Student Attendance and Achievement in Urban Elementary and Middle Schools: An Instrumental Variables Approach. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 47, 434–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkley, W.; Gilman, R.H.; Black, R.E.; Epstein, L.D.; Cabrera, L.; Sterling, C.R.; Moulton, L.H. Effect of water and sanitation on childhood health in a poor Peruvian peri-urban community. Lancet 2004, 363, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.T.; Zulaika, G.; Nyothach, E.; Oduor, C.; Mason, L.; Obor, D.; Eleveld, A.; Laserson, K.F.; Phillips-howard, P.A. Do Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Conditions in Primary Schools Consistently Support Schoolgirls’ Menstrual Needs? A Longitudinal Study in Rural Western Kenya. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 5, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woode, P.K.; Dwumfour-asare, B.; Nyarko, K.B. Cost and e ff ectiveness of water, sanitation and hygiene promotion intervention in Ghana: The case of four communities in the Brong Ahafo region. Heliyon 2018, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, J.E.; Cumming, O. The impact of water, sanitation and hygiene on key health and social outcomes. In Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) and UNICEF; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.issuelab.org/resources/33410/33410.pdf?download=true (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Besha, B.; Guche, H.; Chare, D.; Amare, A.; Kassahun, A.; Kebede, E.; Workineh, Y.; Yeheyis, T.; Shegaze, M.; Yesuf, A.A.; et al. Assessment of Hand Washing Practice and it’s Associated Factors among First Cycle Primary School Children in Arba Minch Town, Ethiopia, 2015. Epidemiology 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Moreno-Martínez, F.J.; Susarte, A.M.H.; Hueso-Montoro, C.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M. Social Determinants of Health, the Family, and Children’s Personal Hygiene: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Response | Intervention n (%) | Control n (%) | Total n (%) | X2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is your current source of drinking water | Tap | 32(15.4) | 45(21.5) | 77(18.5) | 4.863 | 0.433 |

| Borehole | 81(38.9) | 80(38.3) | 161(38.6) | |||

| Well | 6(2.9) | 4(1.9) | 10(2.4) | |||

| Dam | (53925.5) | 40(19.1) | 93(22.3) | |||

| Tanker | 9(4.3) | 12(5.7) | 21(5.00) | |||

| Truck | 28(13.4) | 27(13.0) | 55(13.2) | |||

| Where do you dispose human waste at home | Private latrine | 91(43.8) | 77(36.8) | 168(40.3) | 2.083 | 0.353 |

| Shared latrine | 115(55.3) | 130(62.2) | 245(58.8) | |||

| Open defecation | 2(1.00) | 2(1.0) | 4(1.00) | |||

| What are the times when you wash your hands with soap or ash or sand and clean water | After visiting the toilet | 187(89.9) | 196(93.8) | 383(91.8) | 2.421 | 0.298 |

| Before sleeping | 16(7.7) | 11(5.3) | 27(6.5) | |||

| Before going to the toilet | 5(2.4) | 2(1.0) | 7(1.7) | |||

| I keep my water in a | Clean container | 44(21.2) | 29(13.9) | 73(17.5) | 4.009 | 0.135 |

| Covered container | 52(25.0) | 61(29.2) | 113(27.1) | |||

| Clean covered container | 112(53.8) | 119(56.9) | 231(55.4) | |||

| In which of the following ways do you treat your drinking water to make it safe at home | Boil the water | 45(21.6) | 39(18.7) | 84(20.1) | 5.007 | 0.082 |

| Use a clean cloth to strain the water | 91(43.8) | 114(54.5) | 205(49.2) | |||

| Allow the dirt to settle at the bottom of the container | 72(34.6) | 56(26.8) | 128(30.7) |

| Module | Theory Construct | Content | Strategy | Estimated Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | Information and behavioural skills | Definition of water, sanitation and hygiene, general sources of water in school and at home, sources of clean water. | Lecture, discussion, brainstorming, role play | 1 h 30 min |

| Module 2 | Information and behavioural skills | Water storage | Lectures, brainstorming, and practical’s | 1 h 30 min |

| Module 3 | Information and behavioural skills | Treatment of drinking water | Lectures, discussion, brainstorming | 1 h 30 min |

| Module 4 | Motivation | Prevention of diseases caused by poor WASH practices, participants’ experiences and those of other adolescent girls. | Brainstorming, discussion | 1 h 30 min |

| Module 5 | Information and behavioural skills | Sanitation, Hygiene, Hand Washing Practical CDC | Lectures, discussion, brainstorming, hand washing practical’s | 1 h 30 min |

| Module 6 | Motivation | Preventive measures, community norms, and how best they continue with what they have learnt spreading the information to their peers. | Brainstorming, discussion | 1 h 30 min |

| Variable | Intervention Mean ± SD (n = 208) | Control Mean ± SD (n = 209) | Overall Sample Mean ± SD (n = 417) | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

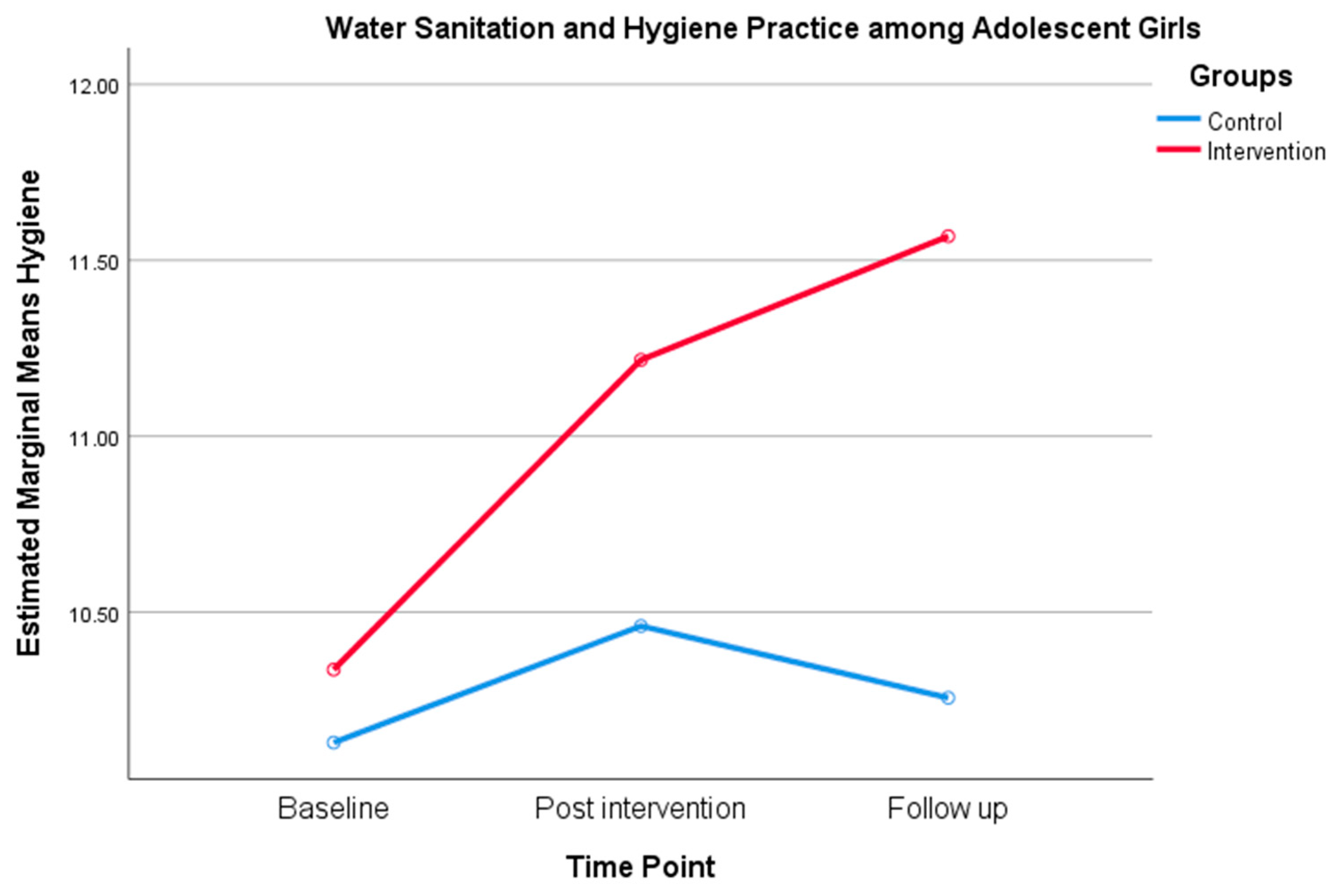

| Hygiene at baseline | 10.34 ± 2.2 | 10.13 ± 2.2 | 10.23 ± 2.2 | −0.976 | 0.330 |

| Hygiene at post intervention | 11.22 ± 2.10 | 10.46 ± 1.77 | 10.84 ± 1.97 | −3.977 | <0.001 * |

| Hygiene at follow up | 11.57 ± 1.89 | 10.26 ± 2.01 | 10.91 ± 2.06 | −6.855 | <0.001 * |

| Group | Time Points for Hygiene Practice | Baseline | Follow up | Mean Difference | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||||

| Intervention group | Time 0 vs. Time 2 | 10.34 ± 2.2 | 11.57 ± 1.89 | −1.23 | −5.995 | <0.001 * |

| Control group | Time 0 vs. Time 2 | 10.13 ± 2.2 | 10.26 ± 2.01 | −0.13 | −0.614 | 0.540 |

| B | SE | Crude Odd Ratio | Wald Chi-Square | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Groups | |||||||

| Control | Ref | ||||||

| Intervention | 0.510 | 0.112 | 1.665 | 20.634 | 1.336 | 2.075 | <0.001 * |

| Time points | |||||||

| Baseline | Ref | ||||||

| Post intervention | 0.571 | 0.149 | 1.770 | 14.728 | 1.322 | 2.368 | <0.001 * |

| Follow up | 0.729 | 0.145 | 2.073 | 25.356 | 1.561 | 2.754 | <0.001 * |

| Age of adolescent girls (Years) | |||||||

| Early adolescents | −0.049 | 0.158 | 0.756 | 0.096 | 0.698 | 1.298 | 0.756 |

| Middle adolescents | −0.227 | 0.126 | 0.797 | 3.231 | 0.622 | 1.021 | 0.072 |

| Late adolescents | Ref | ||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Bura | Ref | ||||||

| Kanuri | 0.201 | 0.191 | 1.222 | 1.102 | 0.840 | 1.778 | 0.294 |

| Hausa | 0.393 | 0.292 | 1.482 | 1.814 | 0.836 | 2.625 | 0.178 |

| Marghi | 0.243 | 0.243 | 1.275 | 0.995 | 0.791 | 2.053 | 0.319 |

| Shuwa | 0.425 | 0.294 | 1.529 | 2.090 | 0.860 | 2.719 | 0.148 |

| Fulani | 0.167 | 0.245 | 1.182 | 0.466 | 0.732 | 1.909 | 0.495 |

| Chibok | 0.319 | 0.292 | 1.376 | 1.195 | 0.776 | 2.440 | 0.274 |

| Gwoza | −0.226 | 0.251 | 0.798 | 0.807 | 0.488 | 1.305 | 0.369 |

| Other ethnic groups | 0.225 | 0.238 | 1.253 | 0.893 | 0.785 | 1.999 | 0.345 |

| Religion | |||||||

| Christianity | Ref | ||||||

| Islam | 0.348 | 0.127 | 1.416 | 7.493 | 1.104 | 1.816 | 0.006 * |

| Place of residence | |||||||

| Rural | Ref | ||||||

| Urban | −0.414 | 0.149 | 0.661 | 7.703 | 0.493 | 0.885 | 0.006 * |

| Monthly income | |||||||

| Less than ₦ 18,000 | Ref | ||||||

| ₦ 18,000–₦ 30,000 | −0.089 | 0.153 | 0.915 | 0.339 | 0.677 | 1.235 | 0.560 |

| ₦ 31,000–₦ 50,000 | −0.349 | 0.178 | 0.705 | 3.859 | 0.498 | 0.999 | 0.049 * |

| ₦ 51,000 and above | −0.337 | 0.162 | 0.714 | 4.315 | 0.520 | 0.981 | 0.038 * |

| Education of father | |||||||

| No education | Ref | ||||||

| Informal education | 0.047 | 0.238 | 1.048 | 0.039 | 0.658 | 1.670 | 0.843 |

| Primary education | −0.641 | 0.323 | 0.527 | 3.928 | 0.279 | 0.993 | 0.048 * |

| Secondary education | 0.141 | 0.202 | 0.868 | 0.489 | 0.584 | 1.291 | 0.485 |

| Tertiary education | −0.140 | 0.193 | 0.869 | 0.523 | 0.595 | 1.270 | 0.469 |

| Age group of mother (Years) | |||||||

| ≤34 | 0.013 | 0.160 | 0.805 | 1.835 | 0.588 | 1.102 | 0.932 |

| 35 to 44 | −0.217 | 0.156 | 1.013 | 0.007 | 0.746 | 1.376 | 0.176 |

| ≥45 | Ref | ||||||

| Occupation of mothers | |||||||

| Civil service | Ref | ||||||

| Trading/business | 0.036 | 0.147 | 1.037 | 0.061 | 0.777 | 1.383 | 0.805 |

| Farming | −0.642 | 0.231 | 0.526 | 7.716 | 0.335 | 0.828 | 0.005 * |

| House wives | −0.080 | 0.143 | 0.923 | 0.310 | 0.697 | 1.223 | 0.577 |

| Family type | |||||||

| Monogamy | Ref | ||||||

| Polygamy | 0.177 | 0.116 | 1.193 | 2.333 | 0.951 | 1.497 | 0.127 |

| Information | |||||||

| Poor information | Ref | ||||||

| Good information | 0.328 | 0.124 | 1.389 | 6.970 | 1.088 | 1.772 | 0.008 * |

| Variables | B | SE | Adjusted Odd Ratio | Wald Chi-Square | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| Intercepts | −0.012 | 0.258 | |||||

| Groups | |||||||

| Control | Ref | ||||||

| Intervention | 0.118 | 0.205 | 1.125 | 0.330 | 0.753 | 1.680 | 0.566 |

| Time points | |||||||

| Baseline | Ref | ||||||

| Post intervention | 0.380 | 0.212 | 1.462 | 3.217 | 0.965 | 2.214 | 0.073 |

| Follow up | 0.301 | 0.197 | 1.351 | 2.334 | 0.918 | 1.988 | 0.127 |

| Interaction | |||||||

| Control *baseline | Ref | ||||||

| Intervention *post intervention | 0.396 | 0.301 | 1.486 | 1.734 | 0.824 | 2.680 | 0.188 |

| Intervention *follow up | 0.911 | 0.299 | 2.487 | 9.273 | 1.383 | 4.469 | 0.002 * |

| Religion | |||||||

| Christianity | Ref | ||||||

| Islam | 0.339 | 0.129 | 1.404 | 6.972 | 1.091 | 1.806 | 0.008 * |

| Place of residence | |||||||

| Rural | Ref | ||||||

| Urban | −0.458 | 0.159 | 0.632 | 8.283 | 0.463 | 0.864 | 0.004 * |

| Monthly income | |||||||

| Less than ₦ 18,000 | Ref | ||||||

| ₦ 18,000–₦ 30,000 | −0.222 | 0.159 | 0.801 | 1.945 | 0.587 | 1.094 | 0.163 |

| ₦ 31,000–₦ 50,000 | −0.339 | 0.181 | 0.712 | 3.533 | 0.500 | 1.015 | 0.060 |

| ₦ 51,000 and above | −0.352 | 0.163 | 0.703 | 4.646 | 0.511 | 0.969 | 0.031 * |

| Occupation of mothers | |||||||

| Civil service | Ref | ||||||

| Trading/business | −0.012 | 0.145 | 1.012 | 0.006 | 0.761 | 1.345 | 0.936 |

| Farming | −0.627 | 0.212 | 0.534 | 6.736 | 0.333 | 0.858 | 0.009 * |

| House wives | −0.108 | 0.141 | 0.897 | 0.590 | 0681 | 1.183 | 0.442 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charles Shapu, R.; Ismail, S.; Ying Lim, P.; Ahmad, N.; Abubakar Njodi, I. Effectiveness of Health Education Intervention on Water Sanitation and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria: A Cluster Randomised Control Trial. Water 2021, 13, 987. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13070987

Charles Shapu R, Ismail S, Ying Lim P, Ahmad N, Abubakar Njodi I. Effectiveness of Health Education Intervention on Water Sanitation and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria: A Cluster Randomised Control Trial. Water. 2021; 13(7):987. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13070987

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharles Shapu, Ruth, Suriani Ismail, Poh Ying Lim, Norliza Ahmad, and Ibrahim Abubakar Njodi. 2021. "Effectiveness of Health Education Intervention on Water Sanitation and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria: A Cluster Randomised Control Trial" Water 13, no. 7: 987. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13070987

APA StyleCharles Shapu, R., Ismail, S., Ying Lim, P., Ahmad, N., & Abubakar Njodi, I. (2021). Effectiveness of Health Education Intervention on Water Sanitation and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria: A Cluster Randomised Control Trial. Water, 13(7), 987. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13070987