Water-Based Therapies of Bhutan: Current Practices and the Recorded Clinical Evidence of Balneotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

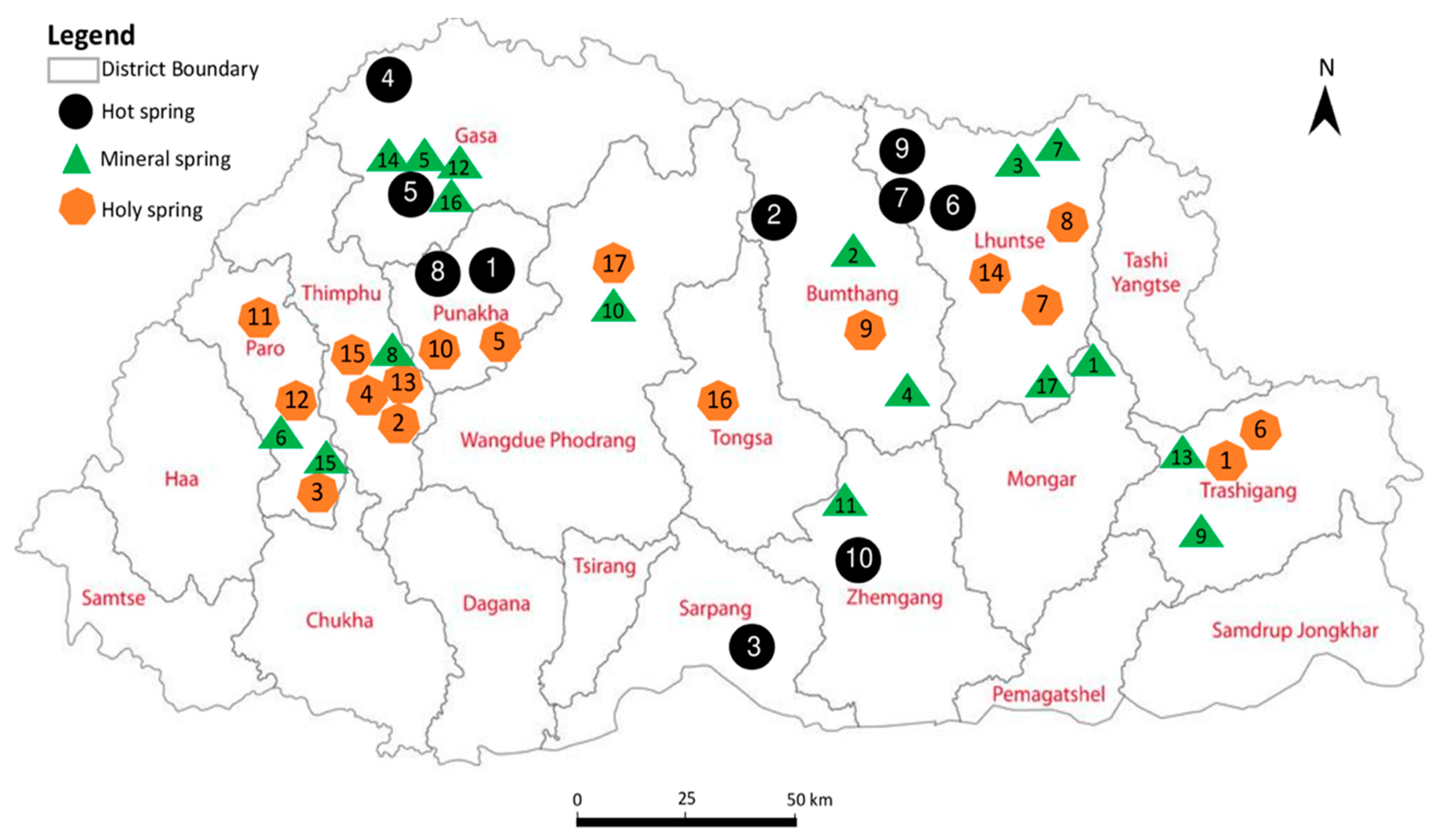

2.1. Study Areas

- Gasa (Gay za and Remey villages under Khamoed gewog) (2100–3826 masl)

- Punakha (Wolathang under Toedwang and Mitsegang under Goen Shari gewog (1737 masl)

- Wangdue Phodrang (Nobding under Dangchu gewog) (2355 masl)

- Thimphu (Kabisa under Kawang gewog) (2393 masl)

- Paro (Dobji dzong under Dokar gewog and Lunyi village under Lunyi gewog) (2080–2110 masl)

- Bumthang (Dur village and Zampa nyipa under Choekhor gewog) (3522–4795 masl)

- Lhuntse (gNey village under Gangzur gewog and Dungkar village under Kurtoe gewog) (2472–2761 masl)

- Mongar (Yarab village under Sershong gewog) (2513 masl)

- Trashigang (Donphangma under Khaling gewog and Rangjung under Radhi gewog) (870–2195 masl)

- Zhemgang (Duenmang hot spring under Nangkor gewog and Wangdigang under Trong gewog) (500–1533 masl)

- Sarpang (Sershong gewog) (332 masl)

2.2. Study Design, Ethics, and the Data Collection Methods

2.3. Field Survey and Identification of Thermal, Medicinal, and Holy Spring Waters

2.4. Data Collection on Steam Bath Therapy and Holy Water and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Types and Classification of Healing Waters in Bhutan

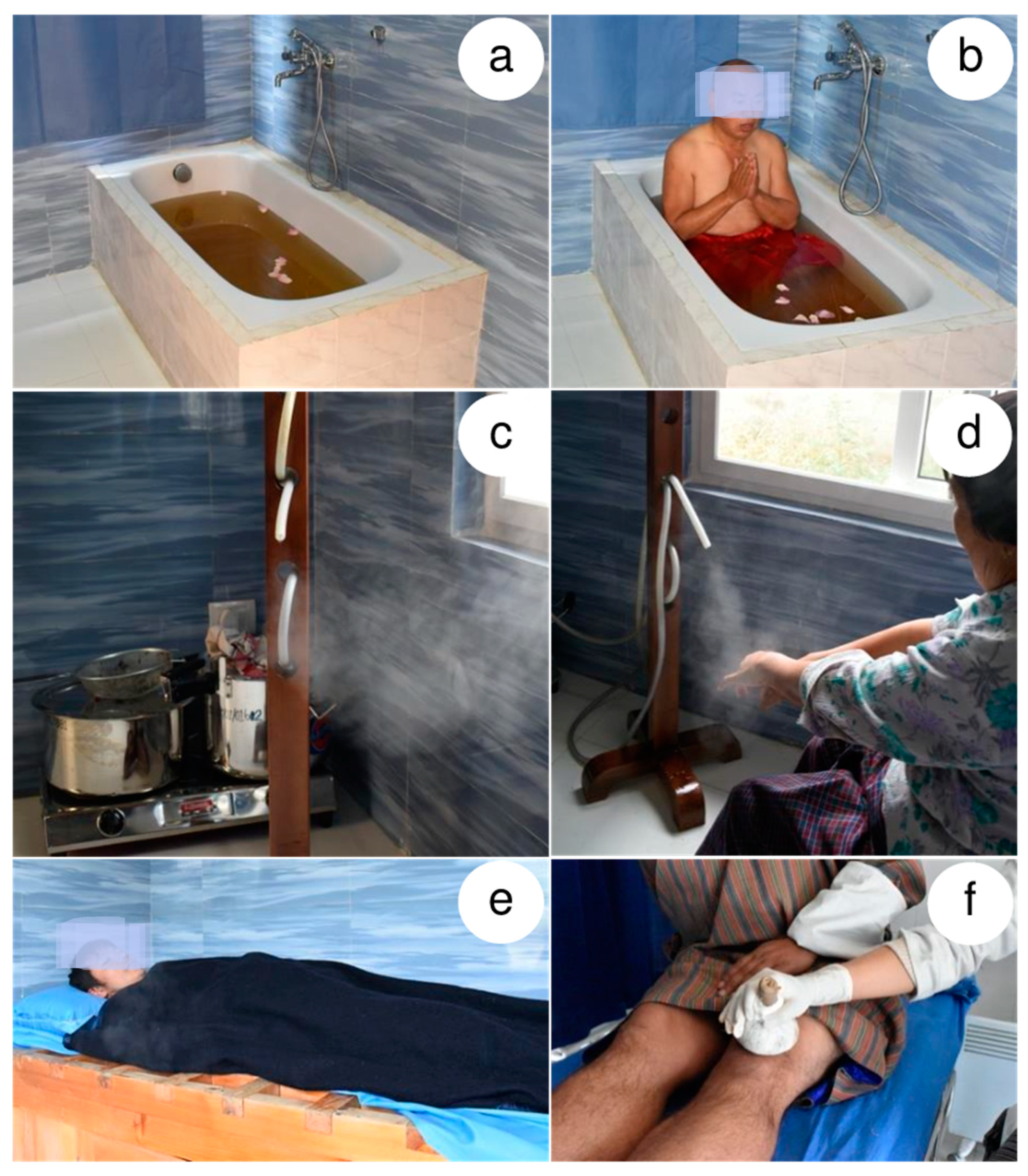

3.2. Herb-Infused Water (bdud-rtsi lnga-lums) Therapy

3.2.1. Herbal Bath Immersion (chu-lums)

3.2.2. Steam Bath (rlang-dugs)

3.2.3. Herbal Steam Bath (rlang-lums)

3.2.4. Herbal Compression (bcing-dugs)

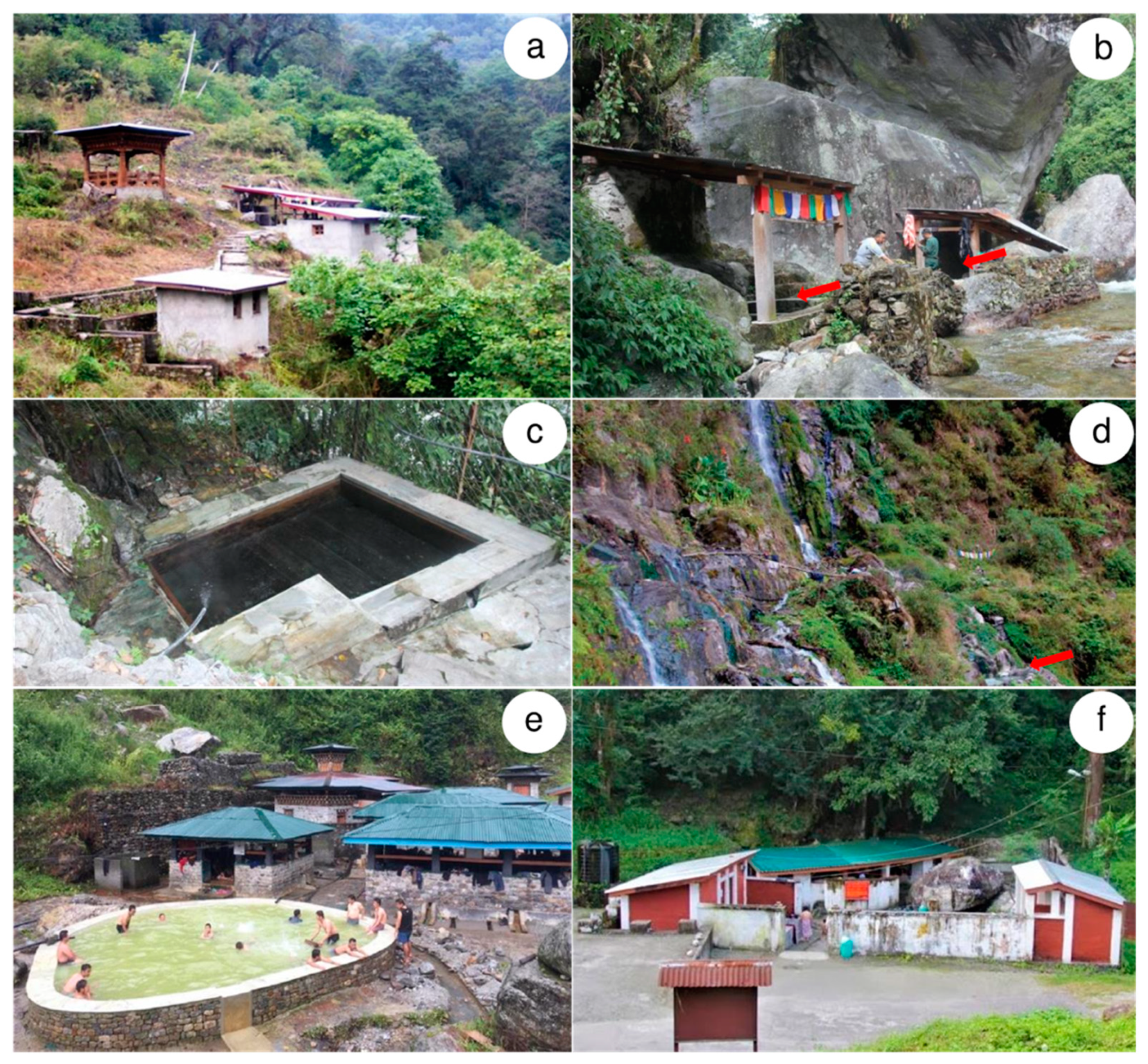

3.3. Balneotherapy

3.3.1. Hot Springs (tsha-chus) in Bhutan

3.3.2. Medicinal or Mineral Springs (sman-chu)

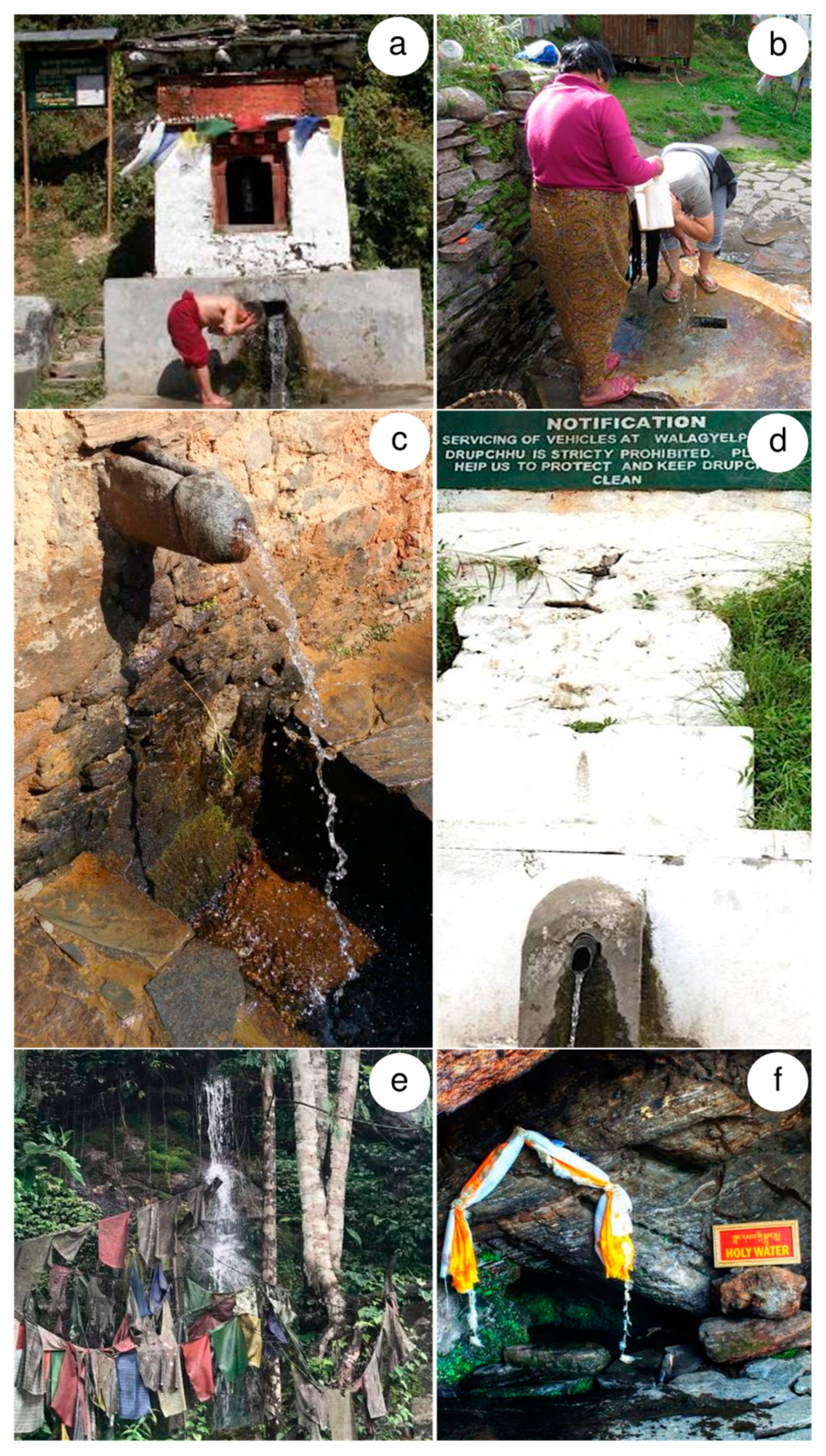

3.3.3. Holy Spring Waters (Sgrub-chu)

3.3.4. Blessed Rainwater (khrus-’bab chu)

3.4. Spiritually Empowered Waters

3.5. Meta-Analysis of the Literature on the Clinical Studies of Balneotherapies

4. Discussion

4.1. Worldwide Practices of MH Accentuating Bhutanese Perspectives

4.2. Quality, Safety and Efficacy of Medical Hydrology in Bhutan

4.2.1. Herbal Bath Therapy

4.2.2. Balneotherapy and Clinical Trials

4.2.3. Spiritually Empowered Holy Waters

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

- Conducting randomized clinical studies on four herbal bath therapies currently offered by the NTMH, Thimphu.

- Determining the pH, microbiological composition, and chemical compositions of all hot springs and mineral springs and develop a comprehensive monograph for geothermal resources in the country.

- Conducting correlational studies between their chemical compositions and traditionally claimed health benefits.

- Formulating an appropriate law and regulations, including compulsory water quality testing of hot springs and mineral springs.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blake, E. Naturopathic hydrotherapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia Syndr. 2010, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarz, T.; Speach, D. Aquatic Physical Therapy. In The Comprehensive Treatment of the Aging Spine; Elsevier BV: Radarweg, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen, A.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Boers, M.; Cardoso, J.R.; Lambeck, J.; De Bie, R.; De Vet, H.C. Balneotherapy (or spa therapy) for rheumatoid arthritis. An abridged version of Cochrane Systematic Review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 51, 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Davinelli, S.; Bassetto, F.; Vitale, M.; Scapagnini, G. Thermal Waters and the Hormetic Effects of Hydrogen Sulfide on Inflammatory Arthritis and Wound Healing. In The Science of Hormesis in Health and Longevity; Elsevier BV: Radarweg, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E.; Karagülle, M.Z.; Karagülle, M. Spa therapy and balneotherapy for treating low back pain: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Rheumatology 2006, 45, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pesce, A. Thermal Spas: An Economic Development Alternative along Both Sides of the Uruguay River. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.483.5345&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Bahadorfar, M. A study of hydrotherapy and its health benefits. Int. J. Res. 2014, 8, 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsis, N.; Polkas, G.; Daoutis, A.; Prokooiou, E.; Kourkouta, L. Hydrotherapy in Ancient Greece. Balk. Mil. Med. Rev. 2013, 16, 462–466. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R. Waters and spas in the classical world. Med. Hist. 1990, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfaldoni, S.; Tchernev, G.; Wollina, U.; Roccia, M.G.; Fioranelli, M.; Gianfaldoni, R.; Lotti, T. History of the Baths and Thermal Medicine. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablin, J.J.; Häuser, W.; Buskila, D. Spa Treatment (Balneotherapy) for Fibromyalgia—A Qualitative-Narrative Review and a Historical Perspective. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, H.; Orion, E.; Wolf, R. Balneotherapy in dermatology. Dermatol. Ther. 2003, 16, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonpo, Y.Y. The Subsequent Tantra from the Secret Quintessential Instructions on the Eight Branches of the Ambrosia Essence Tantra; Men-Tsee-Khang Publications: Dharamsala, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gonpo, Y.Y. The Root Tantra and the Explanatory from the Secret Quintessential Instructions on the Eight Branches of the Ambrosia Essence Tantra; Men-Tsee-Khang Publications: Daramsala, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yuri, P.; Dorje, G.; Meyer, F. Tibetan Medical Paintings: Illustrations to the ‘Blue Beryl’ Treatise of Sangs Rgyas Rgya Mtsho; Serindia Publications: London, UK, 1992; pp. 1653–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Yonten, P. External Therapies in Tibetan Medicine: The Four Tantras, Contemporary Practice, and a Preliminary History of Surgery. In Bodies in Balance—The Art of Tibetan Medicine; Theresia, H., Ed.; Rubin Museum of Art and University of Washington Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 64–89. [Google Scholar]

- Katharina, S. Kalte Kräuter und heiße Bäder: Die Anwendung der Tibetischen Medizin in den Köstern Amdos. In Wiener Ethnomedizinische Reihe: Band 5; Lit.: Wien, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Katharina, S. External Treatments at Kumbum Monastery Hospital. Vienn. Ethnomedicine Newsl. 2005, 7, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk, P.; Pyne, S.G.; Keller, P.A. An assessment of the Bhutanese traditional medicine for its ethnopharmacology, ethnobotany and ethnoquality: Textual understanding and the current practices. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangchuk, P.; Yeshi, K.; Jamphel, K. Pharmacological, ethnopharmacological, and botanical evaluation of subtropical medicinal plants of Lower Kheng region in Bhutan. Integr. Med. Res. 2017, 6, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Namgay, K.; Gayleg, K.; Dorji, Y. Medicinal plants of Dagala region in Bhutan: Their diversity, distribution, uses and economic potential. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshi, K.; Gyal, Y.; Sabernig, K.; Phuntsho, J.; Tidwell, T.; Jamtsho, T.; Dhondup, R.; Tokar, E.; Wangchuk, P. An integrated medicine of Bhutan: Sowa Rigpa concepts, botanical identification, and the recorded phytochemical and pharmacological properties of the eastern Himalayan medicinal plants. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshi, K.; Morisco, P.; Wangchuk, P. Animal-derived natural products of Sowa Rigpa medicine: Their pharmacopoeial description, current utilization and zoological identification. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 207, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshi, K.; Wangdi, T.; Qusar, N.; Nettles, J.; Craig, S.R.; Schrempf, M.; Wangchuk, P. Geopharmaceuticals of Himalayan Sowa Rigpa medicine: Ethnopharmacological uses, mineral diversity, chemical identification and current utilization in Bhutan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 223, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P.; Pyne, S.G.; Keller, P.A. Ethnobotanical authentication and identification of Khrog-sman (Lower Elevation Medicinal Plants) of Bhutan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phuntshok. Shel-Gong-Shel-Phreng; T.M.A.I. Publishers: Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dorje, G. Khrungs-d.pe-dri-med-shel-gyi-me-long (Immaculate Crystal Mirror of Materia Medica Illustrations); Mi Rigs Dpe Skrun Khang: Beijing, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dorji, Y. ‘Brug-Gi Tshachu Dang Smanchu Rnam-Bshad ‘Chi-Med Bdud-Rtsi’i Bum-Bzang. ‘Brug Nang Sman Zhib-‘Tshol Dang Gong-‘Phel Tshogs-pa; Nang-pa’i Gso-Rig ‘Bzin-Skyong-lte-ba; Institute of Traditional Medicine Services: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pentecost, A. Hot springs, thermal springs and warm springs. What’s the difference? Geol. Today 2005, 21, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentecost, A.; Jones, B.; Renaut, R.W. What is a hot spring? Can. J. Earth Sci. 2003, 40, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuntsho, K. Thruebab, the Descent of Blessed Water. Kuenselonline (National Newspaper). Available online: https://kuenselonline.com/trhuebab-the-descent-of-blessed-water/ (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Falagas, M.E.; Zarkadoulia, E.; Rafailidis, P.I. The therapeutic effect of balneotherapy: Evaluation of the evidence from randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2009, 63, 1068–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhao, Z. Chinese herbal bath therapy for the treatment of uremic pruritus: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, A.; Giannitti, C.; Bellisai, B.; Iacoponi, F.; Galeazzi, M. Efficacy of balneotherapy on pain, function and quality of life in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2011, 56, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Hayasaka, S.; Kurihara, S.; Nakamura, Y. Physical and Mental Effects of Bathing: A Randomized Intervention Study. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 9521086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Iwawaki, Y.; Takishita, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Murota, M.; Yoshioka, S.; Hayano, A.; Hosokawa, T.; Yamanaka, R. Effects and safety of mechanical bathing as a complementary therapy for terminal stage cancer patients from the physiological and psychological perspective: A pilot study. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 47, 1066–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, J.; Grebe, J.; Kaifel, S.; Weinert, T.; Sadaghiani, C.; Huber, R. Effects of hyperthermic baths on depression, sleep and heart rate variability in patients with depressive disorder: A randomized clinical pilot trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier-Jarmer, M.; Frisch, D.; Oberhauser, C.; Immich, G.; Kirschneck, M.; Schuh, A. Effects of single moor baths on physiological stress response and psychological state: A pilot study. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lin, J.; Qin, Q.-Z.; Han, L.-L.; Chen, Y. Spa therapy (balneotherapy) relieves mental stress, sleep disorder, and general health problems in sub-healthy people. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 62, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapolienė, L.; Razbadauskas, A.; Jurgelėnas, A. The Reduction of Distress Using Therapeutic Geothermal Water Procedures in a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Adv. Prev. Med. 2015, 2015, 749417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rapolienė, L.; Razbadauskas, A.; Sąlyga, J.; Martinkėnas, A. Stress and Fatigue Management Using Balneotherapy in a Short-Time Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 9631684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkuk, K.; Gürdal, H.; Karagülle, M.; Barut, Y.; Eröksüz, R.; Karagülle, M.Z. Balneological outpatient treatment for patients with knee osteoarthritis; an effective non-drug therapy option in daily routine? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 61, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, A.; Celik, S.U.; Evcik, D.; Atman, E.D.; Elhan, A.H.; Genc, V. Balneotherapy is an alternative treatment for mastalgia; a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 19, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-J.; Choi, H.; Tae, B.S.; Lee, M.-G.; Lee, S.J.; Hong, K.D. Short-term benefits of balneotherapy for patients with chronic pelvic pain: A pilot study in Korea. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 40, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, A.; Manica, P.; Bortolotti, R.; Cevenini, G.; Tenti, S.; Paolazzi, G. Is balneotherapy effective for fibromyalgia? Results from a 6-month double-blind randomized clinical trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 37, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzel, A.; Horvát, K.; Molics, B.; Berényi, K.; Németh, B.; Szendi, K.; Varga, C. Clinical improvement of patients with osteoarthritis using thermal mineral water at Szigetvár Spa—results of a randomised double-blind controlled study. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 62, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagülle, M.; Kardeş, S.; Karagülle, O.; Dişçi, R.; Avcı, A.; Durak, I.; Karagülle, M.Z. Effect of spa therapy with saline balneotherapy on oxidant/antioxidant status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 61, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáti, T.; Tefner, I.K.; Kovács, L.; Hodosi, K.; Bender, T. The effects of the calcium-magnesium-bicarbonate content in thermal mineral water on chronic low back pain: A randomized, controlled follow-up study. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, S.; Vittadini, F.; Ferroni, C.; Bosco, A.; Serra, R.; Frigo, A.C.; Frizziero, A. The role of thermal balneotherapy in the treatment of obese patient with knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin-Onat, Ş.; Taşoğlu, Ö.; Özişler, Z.; Güneri, F.D.; Özgirgin, N. Balneotherapy in the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Controlled Study. Arch. Rheumatol. 2015, 30, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzichi, L.; Da Valle, Y.; Rossi, A.; Giacomelli, C.; Sernissi, F.; Giannaccini, G.; Betti, L.; Ciregia, F.; Giusti, L.L.; Scarpellini, P.; et al. A multidisciplinary approach to study the effects of balneotherapy and mud-bath therapy treatments on fibromyalgia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2013, 31, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hanzel, A.; Berényi, K.; Horváth, K.; Szendi, K.; Németh, B.; Varga, C. Evidence for the therapeutic effect of the organic content in Szigetvár thermal water on osteoarthritis: A double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péter, I.; Jagicza, A.; Ajtay, Z.; Boncz, I.; Kiss, I.; Szendi, K.; Kustán, P.; Németh, B. Balneotherapy in Psoriasis Rehabilitation. In Vivo 2017, 31, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysteinsdóttir, J.H.; Ólafsson, J.H.; Agnarsson, B.A.; Lúðvíksson, B.R.; Sigurgeirsson, B. Psoriasis treatment: Faster and long-standing results after bathing in geothermal seawater. A randomized trial of three UVB phototherapy regimens. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2013, 30, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungsukruthai, P.; Nootim, P.; Worakunphanich, W.; Tabtong, N. Efficacy and safety of herbal steam bath in allergic rhinitis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 16, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merry, A.M. More than a bath: An examination of Japanese bathing culture. CMC Sr. Theses 2013, 665. Available online: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/665 (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Wojcikowski, K.; Johnson, D.W.; Gobe, G. Herbs or natural substances as complementary therapies for chronic kidney disease: Ideas for future studies. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2006, 147, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.S.; Rawat, G.S.; Desk, S. Sowa-Rigpa: A Healthcare Practice in Trans-Himalayan Region of Ladakh, India. SDRP J. Plant Sci. 2017, 2, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. China’s Lum Medicinal Bathing of Sowa Rigpa Listed as Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2018. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-11/28/c_137637836.htm (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Fleming, S.A.; Gutknecht, N.C. Naturopathy and the Primary Care Practice. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2010, 37, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, H. Below the radar innovations and emerging property right approaches in Tibetan medicine. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2017, 20, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbulea, M.; Payyappallimana, U. Onsen (hot springs) in Japan—Transforming terrain into healing landscapes. Health Place 2012, 18, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-M.; Song, S.-R.; Chen, Y.-L.; Tsao, S. Characteristics and Origins of Hot Springs in the Tatun Volcano Group in Northern Taiwan. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2011, 22, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangdi, N.; Dorji, T.; Wangdi, K. Hotsprings and Mineral Springs of Bhutan; UWICE Press: Lamai Goempa, Bumthang, Bhutan, 2014.

- Wangchuk, P.; Dorji, Y. Historical Roots, Spiritual Significance and the Health Benefits of mkhempa-ljong gnyes Tshachu in Lhuentse. J. Bhutan Stud. 2007, 16, 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, J. The influence of mineral water solutions in phototherapy. Clin. Dermatol. 1996, 14, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajo, J.M.; Maraver, F. Sulphurous mineral waters: New applications for health. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2017, 2017, 8034084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, R. Mineral water and spas in Israel. Clin. Dermatol. 1996, 14, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Kimura, H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H. Hydrogen Sulfide and Polysulfides as Biological Mediators. Molecules 2014, 19, 16146–16157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvigo, R.; Epstein, N. Spiritual Bathing: Healing Rituals and Traditions from around the World; Celestial Arts: Berkely, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oestigaard, T. Holy water: The works of water in defining and understanding holiness. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2017, 4, e1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, J.A. The significance of the mode of baptism. WRS J. 2007, 14, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hara, K. Aspects of Shinto in Japanese Communication. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2003, 12, 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Jawaid, T. Cinnamomum camphora (Kapur): Review. Pharmacogn. J. 2012, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzabri, I.; Addi, M.; Berrichi, A. Addi Traditional and Modern Uses of Saffron (Crocus Sativus). Cosmetics 2019, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangchuk, P. Tashi Quality assurance of the university medical education, hospital services and traditional pharmaceutical products of the Bhutanese So-wa-rig-pa health care system. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoH. Manual on Traditional Medicine Information Management System; National Traditional Medicine Hospital, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of health (MoH): Kawa Jangsa, Thimphu, Bhutan, 2010.

- MoH. Standard Operating Procedures for Traditional Medicine Services; National Traditional Medicine Hospital, Traditional Medicine Division (DMS), Ministry of Health: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2012.

- MoH. Collaborative Referral Guideline on Mental Health Care Services; Division of Local Healing and Spiritual Health, Department of Traditional Medicine Services, Ministry of Health: Thimphu, Bhutan, 2016.

- Wangdi, S. An enquiry into the efficacy of Dutsi-nga-lum, a unique healing therapy in the Traditional Bhutanese Medicine. sMen-jong gSo-rig J. 2015, 7, 1–6. Available online: http://www.ftm.edu.bt/wp-content/uploads/docs/English%20Journals/Perceived%20benefits%20of%20dutsi-nga-lum.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Li, L.; Ma, Z. (Sam) Global Microbiome Diversity Scaling in Hot Springs with DAR (Diversity-Area Relationship) Profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, C.; Rameez, M.J.; Haldar, P.K.; Peketi, A.; Mondal, N.; Bakshi, U.; Mapder, T.; Pyne, P.; Fernandes, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; et al. Microbiome and ecology of a hot spring-microbialite system on the Trans-Himalayan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburto, A.; Shahsavari, E.; Cohen, M.; Mantri, N.; Ball, A.S. Analysis of the Microbiome (Bathing Biome) in Geothermal Waters from an Australian Balneotherapy Centre. Water 2020, 12, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghilamicael, A.M.; Boga, H.I.; Anami, S.E.; Mehari, T.; Budambula, N.L.M. Potential human pathogenic bacteria in five hot springs in Eritrea revealed by next generation sequencing. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, K.B.; Henson, J.M.; Ferris, M.J. Legionella Species Diversity in an Acidic Biofilm Community in Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mohamed, Z.A. Toxic cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in public hot springs in Saudi Arabia. Toxicon 2008, 51, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Ahmed, I.; Salam, N.; Kim, B.-Y.; Singh, D.; Zhi, X.-Y.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.-J. Diversity and Distribution of Thermophilic Bacteria in Hot Springs of Pakistan. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeriani, F.; Margarucci, L.M.; Spica, V.R. Recreational Use of Spa Thermal Waters: Criticisms and Perspectives for Innovative Treatments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, J.M.; Hutt, J.A.; Rein, K.; Boggs, S.E.; Barr, E.B.; Fleming, L.E. The toxicity of microcystin LR in mice following 7 days of inhalation exposure. Toxicon 2005, 45, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, R. the toxicology of microcystins. Toxicon 1998, 36, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, W.W.; Azevedo, S.M.; An, J.S.; Molica, R.J.; Jochimsen, E.M.; Lau, S.; Rinehart, K.L.; Shaw, G.R.; Eaglesham, G.K. Human fatalities from cyanobacteria: Chemical and biological evidence for cyanotoxins. Environ. Health Perspect 2001, 109, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabuuchi, E.; Wang, L.; Arakawa, M.; Yano, I. Distribution of Legionellae in Hot Spring Bath Water in Japan. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1994, 68, 549–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ohno, A.; Kato, N.; Yamada, K.; Yamaguchi, K. Factors Influencing Survival of Legionella pneumophila Serotype 1 in Hot Spring Water and Tap Water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 2540–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroki, T.; Amemura-Maekawa, J.; Ohya, H.; Furukawa, I.; Suzuki, M.; Masaoka, T.; Aikawa, K.; Hibi, K.; Morita, M.; Lee, K.-I.; et al. Outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease Caused by Legionella pneumophila Serogroups 1 and 13. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, M.A.K.; Jacob, J.H.; Hussein, E.; Masadeh, M.M.; Obeidat, S.M.; Juhmani, A.-S.F.; Al-Razaq, M.A.A. Microbiological analysis, antimicrobial activity, and heavy-metals content of Jordanian Ma’in hot-springs water. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocco, P.B. Mineralwasser als Heilmittel [Mineral water as a cure]. Veroff. Schweiz. Ges. Gesch. Pharm. 2008, 29, 13–402. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner, A.; Atteneder, M.; Schmidhuber, A.; Knetsch, S.; Farnleitner, A.H.; Sommer, R. Holy springs and holy water: Underestimated sources of illness? J. Water Health 2012, 10, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Types of Herbal Therapy | Ethnopharmacological Uses |

|---|---|

| Herbal bath immersion | Used for treating gout, arthritis, neurological disorders, stiffness or paralysis of limbs, injury or illness affecting legs or foot, boil or tumor, large ulcer or sore, fresh, and old wounds, stomach ulcer, swellings, hunchback or kyphosis, severe illness, dislocated disc, serous fluid accumulated between flesh and bone, and a sickness of cold character caused by phlegm and wind disorders. |

| Herbal steam bath | Indicated for post-traumatic pain, swelling of hands and legs, neurological disorder, muscular dystrophy, trembling, obstinate skin diseases, piles, chronic fever, gouts, arthritis, and rheumatism. It also provides relaxation to the stressful mind and body, and depression. It is also indicated for bile or phlegm disorders, and wind disorders. |

| Localized herbal steaming | Same to steam bath. |

| Herbal compression | Used for treating gout, arthritis, periarthritis, cervical spondylosis, varicose veins, psoriasis, sprain, sciatica, muscle dystrophy, obstinate skin diseases, spasm, gastritis, sinusitis, lower backache, paralysis, and trauma. |

| Name of Hot Spring | Pool No. | Pool Name | Location | Altitude (masl) | Temperature (°C) | Hot Spring Category | Ethnopharmacological Benefits [28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chuboog (1) | 1 | Upper pool | Wolathang under Toewang gewog, Punakha | 1737 | 39.9 | Warm spring | Heals serous fluid associated with cold disorders, which include urinary tract infection and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). It also cures skin diseases, chronic stomach-ache and other diseases related to evil afflictions. |

| 2 | Lower pool | 43.5 | Hot spring | Heals indigestion, cold disorders, indigestion and increasing mucus because of suppressed wind, and weak and painful eyes. It is also useful against stomach ailments, muscle sprains, diabetes, and certain forms of phlegm diseases. | |||

| Dur (2) | 1 | Chenrayzig pool | Dur under Choekhor gewog, Bumthang | 3522 | 40.2 | Warm spring | Heals Indigestion and alleviates phlegm diseases, dropsy, paralysis, poisonings, neurological disorder, indigestion, and vision effects. |

| 2 | Zerkham pool | 38.3 | Warm spring | Heals phlegm diseases, paralysis, and pustule, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and colic or spasm. | |||

| 3 | Drangwa mo pool | 42.0 | Warm spring | Useful for treating cold disorder, backache, and a woman’s irregular menstrual period. Additionally, heals stomach pain and backache resulting from phlegm disorders, STDs such as syphilis and gonorrhea particularly for females. | |||

| 4 | Drangwa pho pool | 43 | Hot spring | Therapeutic properties are almost same to Drangwa mo hot spring, but it is beneficial more to males. Helpful in treating stomach pain resulting from phlegm disorders, heals kidney disorders, alleviates urinary retention caused by stones, cold rheumatism affecting joints of the limbs, water swelling diseases, swelling or edema, and dropsy in the chest, arthritis, indigestion, gastritis, and kidney disorders. | |||

| 5 | Gunad pool | 43 | Hot spring | Improves skin texture and glow and assuage defective bile, wind disorders, pain and swelling and wounds caused by evil afflictions, chronic and acute headaches. First bathing should be done here and then continue to the rest. | |||

| 6 | Guru pool | 42.0 | Warm spring | Useful for alleviating brown phlegm, chronic fevers, rheumatism and gout, pus, or serous fluid, and healing skin diseases and malignant tumor. Locality believes it has power to heal almost all the diseases. | |||

| 7 | Badkan pool | 38 | Warm spring | Useful for phlegm disorders. | |||

| Gelephu (3) | 1 | Pond 1 | Shershong gewog, Sarpang | 332 | 34.0 | Tepid spring | Heals serous fluid that results from cold, swelling or edema, skin diseases, gout, rheumatism, kidney disorders, and phlegm disorders, hypertension, tumors, conjunctivitis, dropsy, and chronic fever. |

| 2 | Pond 2 | 36.4 | Warm spring | Same as Pool 1. | |||

| 3 | Pond 3 | 38.1 | Warm spring | Same as Pool 1 & 2. | |||

| 4 | Pond 4 | Normal cool water | Cold spring | Same as Pool 1, 2 & 3 but rarely used, as it is cold. | |||

| Gayza (4) | Gayza village under Gayza gewog, Gasa | 3826 | NA | Useful for people suffering from poisoning, conjunctivitis, arthritis, and inflammation. | |||

| Gasa (5) | 1 | Pond with limestone | Near bank of Mo chu river, Gasa | 2100 | 41.0 | Warm spring | It is a general detoxifier for all poisons and heals indigestion. It also helps to assuage brown phlegm and phlegm disorders indigestion and increasing mucus because of suppressed wind. |

| 2 | Pond with sulfur nativum | 40.50 | Warm spring | Cures diseases caused by the subterranean spirits called bhupati or lord of earth which are usually associated with festering wounds such as leprosy. Additionally, useful for treating unwanted serous fluid accumulation in joints and lymph in the tissues. Improves facial beauty, alleviates itching disorders, large pustule, and large ulcer or sore. | |||

| 3 | Pond with hot water percolating from rocks | 40.1 | Warm spring | It is a detoxifier, especially for poisoning caused by precious metals. Additionally, heals fracture, rigidity, or stiffness of the limbs, and swelling in the joints. | |||

| 4 | Pond with suphur | 41.5 | Warm spring | Heals serous fluids including that from cold disorders. | |||

| Khambalung gNey (6) | 1 | Guru pool | gNey village under Gangzur gewog, Lhuntse | 2472 | 40.2 | Warm spring | Helpful in treating indigestion, phlegm disorders, weak and painful eyes, and various cold disorders that include urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases. It also cures skin diseases including scabies and heals bone fractures and chronic wounds. |

| 2 | Tshepagmay pool | 40 | Warm spring | Helpful in treating convulsions, indigestion, indigestion and increasing mucus because of suppressed wind, serous fluids, skin diseases, bone and tendon disorders, and muscular atrophy. It also cures skin diseases including scabies and heals bone fractures and chronic wounds. | |||

| 3 | Khadro Yeshey Tshohyal pool | 40.3 | Warm spring | Helpful in treating serous fluid and gout, rheumatoid arthritis, polio, and paralysis. It cures skin diseases including scabies and heals bone fractures and chronic wounds. | |||

| Pasalum (7) | NA | Gangzur gewog, Lhuntse | 4795 | Known to cure thirteen different diseases and ailments. Useful against headache, backache, and stomachache. | |||

| Koma (8) | 1 | Pool 1 | Near Tshori zam, Punakha | 1839 | 38.3 | Warm spring | Alleviates wind disorders, bile disorders, dizziness, defective bile, and complicated convulsions, headache, and lost vision. |

| 2 | Pool 2 | 33.20 | Tepid spring | Heals skin diseases, indigestion, stiff muscles, festering wounds, fractures, serous fluids, increasing mucus because of suppressed wind, swellings, inflicted by evil spirits and combined disease of defective wind and bile. | |||

| 3 | Pool 3 | 38.3 | Warm spring | Good for joint pain, chronic tumor, and anal fistula. | |||

| Yoenten Kuenjung (9) | 1 | Pool 1 | gNey village under Gangzur gewog, Lhuntse | 2761 | NA | NA | Useful for memory disorders. |

| 2 | Pool 2 | NA | NA | Used for bathing before dipping into pool 1. | |||

| Duenmang (10) | 1 | Pool 1 | On a steep cliff of Kamjong under Nangkor gewog, Zhemgang | 500 | 40.7 | Warm spring | Heals indigestion and improves the bodily heat; phlegm disorders, gout or feeling of lameness in the lambs. People often visit this pool to cure goiters, joint pain, sinusitis, skin diseases, headaches, and tuberculosis. |

| 2 | Pool 2 | 45.2 | Hot spring | Heals complicated convulsions, removes bodily poisons, and alleviates both chronic fevers, and feeling of lameness in the lambs. | |||

| 3 | Pool 3 | 49.0 | Hot spring | Same source as Pool 2 and thus has same medicinal properties, though people visit to alleviate particularly headaches. | |||

| 4 | Pool 4 | 43.0 | Hot spring | Same source as Pool 2 & 3 and thus has same medicinal properties, though people visit it to heal particularly skin diseases. |

| Mineral Spring (sman-chu) Names | Location | Altitude (masl) | Organoleptic Properties | Ethnopharmacological Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aja (1) | Serzhong gewog, Mongar | 2513 | NA | Believed to cure 18 different types of diseases (nad-rigs bco-rgyad in Sowa rigpa); useful for tuberculosis, body aches, ulcers, and whooping cough. |

| Baykan (2) | Choekor gewog, Bumthang | 3365 | Rock salt odor | Useful for phlegm disorders. |

| Bharab (3) | Dungkar gewog, Lhuntse | 1770 | Sweet and sour in taste. Has Peacock feather color. | Drinking it alleviates combined disease of wind and defective bile, arthritis, body aches, and tuberculosis, and maternity sickness. |

| Draagchu (4) | Ura Gewog, Bumthang | 3090 | NA | Useful for arthritis, stomach-aches, skin diseases, and eye disorders. |

| Bjagay (5) | Khatoe Gewog, Gasa | 2316 | Sour in taste. Light in nature. | Alleviates phlegm and bile disorders, arthritis, and joint pains. |

| Bjagay (6) | Lunyi gewog, Paro | 2110 | NA | Useful for fractures, ulcers, cardiac diseases, physical wounds, and arthritis. |

| Chethgang (7) | Dungkar gewog, Lhuntse | 1900 | NA | Known for healing arthritis, body aches, and tuberculosis. |

| Kabisa (8) | Kawang gewog, Thimphu | 2393 | Sour and sweet in taste. Darkish in color and heavy in nature. | Stir and inhaling the vapor can alleviate defective bile and wind disorders, joint pains, and stomach-aches. It can also heal complications developed after delivery in women. |

| Dhonphangma (9) | Khaling gewog, Trashigang | 2195 | NA | Useful for dizziness and headaches. |

| Dangchu-Wangchu (10) | Dangchu gewog, Wangdue phodrang | 2355 | Sweet and sour in taste. Sky blue in color. | Believed to be useful for 13 different types of disease (nad-rigs bcu-gsum in Sowa rigpa). Useful for general disorders since it is considered as a detoxifier. |

| Dangkhar (11) | Wangdigang, Zhemgang | 1533 | NA | Useful against headaches, hemorrhoids, tetanus, swollen limbs, joint pains, and ulcers. |

| Loyee (12) | Khatoe gewog, Gasa | 2666 | Sweet and sour in taste. Inhabited by green algae. It is viscous and heavy in nature. | Drinking it progresses good sleep. Bathing with it moisturizes and soften the skin. It heals wind disorders, asthma, and tuberculosis inside lungs. |

| Khabtey (13) | Trashigang | 870 | NA | Useful for joint pains, backaches, fever, arthritis, and tuberculosis. |

| Tokay (14) | Khatoe gewog, Gasa | 2518 | Sour in taste, light in nature. | Heals phlegm, headache, and blood disorders, gastritis, headaches, and stomach-aches. |

| Dobji or Milarepa’s (15) | Dokar gewog, Paro | 2080 | Taste like normal drinking water | It can heal fractures, disease induced by cold, dyspepsia, blood pressure, backache, urinary tract infections, cancer, food poisoning, ulcers, diabetes, and cancer. |

| Mage-phenday (16) | Khatoe Gewog, Gasa | 2666 | NA | Cures sore infections, inflamed wounds, and other skin diseases. |

| Menchugang pho-mo (17) | Tsenkhar gewog, Lhuntse | 2095 | NA | Useful for STDs and dermal disorders such as scabies and leprosy. |

| Holy Spring | Location | Altitude (masl) | Ethnopharmacological Uses [28] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bartsham (1) | Bartsham, Trashigang | 1658 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Dechenphug (2) | Dechenphug lhakhang, Thimphu | 2659 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Dhobdrek (3) | Dobji dzong, Paro | 2011 | Used for healing stomach inflammation, headache, wounds, tumors, warts, blood pressure, and as tonic water. Further beneficial for cleansing sins and defilements. |

| Dhodhey Drak (4) | Dodeydrak monastery, Thimphu | 2500 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Drubthob Nga gi Rinchen (5) | Punakha | 1242 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Jomorichu (6) | Bidung, Trashigang. | 1647 | Treating tumors, headaches, and general ailments. |

| Khamphug (7) | Lhuntse | 1610 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Khandro Drowa Zangmoi Othoe (8) | Lhuntse | 1610 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Kurje (9) | Kurje, Bumthang | 2800 | Popular for treating eye disorders, wounds, and mental disorders. |

| Pelzo Gyem (10) | Thinleygang, Punakha | 2100 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Taktshang (11) | Taktshang, Paro | 3120 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Tamchoe (12) | Tomchoe Lhakhang, Paro | 2156 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Tango (13) | Tango monastery, Thimphu | 2800 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Terton Peling (14) | Lhuntse | 1610 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Thuji Drak (15) | Phajoding monastery, Thimphu | 3650 | Cleansing defilements and believed to be a remedy for people with speech difficulty. |

| Tsheringma (16) | Tshangkha, Trongsa | 2300 | Treatment of throat related disorders and for progressing melodious voice. |

| Woolha Gyalp (17) | Wangdue- phodrang | 1273 | Cleansing defilements. |

| Disease Category | Study Design and Treatment Arms | Study Type & Study Population | Clinical Parameters Examined | Outcomes of the Study | Geographical Area (GA) and Thermal Water Composition (TWC) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee osteoarthritis (Report 1) | Group I (n = 30): spa bath alone. Group II (n = 30): continued with daily care routine. Group I patients treated for 20 min in a bathtub for 12 applications for 2 weeks. Assessment: baseline, 2 w, and after 3 months. TM: both groups given pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. | Prospective randomized, single blind controlled trial. 60 patients. | Pain using visual analogue scale (VAS), Lequesne Index of Severity, Womac Index for knee OA total pain score (W-TPS), total stiffness score (W-TSS), total physical function score (W-TPFS), Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS), Quality of Life (QoL) using Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36). | At week 2: assessment of pain showed significant reduction in Group I (VAS, W-TPS, W-TSS, W-TPFS, p < 0.001); Lequesne index score (p < 0.001); Group II showed no significant difference from baseline (p = 0.33 in W-TPS, p = 0.85 in W-TSS, p = 0.75 in W-TPFS). SF-36 for Group I showed significant improvement (p < 0.001). Significance difference persisted during follow-up. After 3 months: significant reduction in the AIMS score in Group I (p < 0.001) and lasted during follow-up period. Group II showed no significance (p = 0.87). Significant reduction in the NSAID and acetaminophen consumption in Group I (p < 0.001). Non-significant in Group II. | GA: Siena, Italy TWC: 38 °C rich in Ca++, HCO3−, SO4− | [34] |

| General physical and mental effects. | Group I (n = 19) Group II (n = 19) Both groups received 2 w intervention of immersion bathing for 10 min followed by 2 w shower bathing or vice versa. Assessment: baseline, 2 w for each intervention. TM: no additional. | Randomized intervention study. 38 healthy adults. | Self-reported health status measure using VAS, health and mood state during intervention period measured using Japanese versions of 8-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-8) and a short form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS). | VAS scores significantly higher for self-reported health and skin (p < 0.10), and for smile (p < 0.05) during bathing intervention. Additionally, significantly lower VAS score for fatigue, stress, and pain (p < 0.05) during bathing intervention than showering intervention. SF-8 score significant in bathing intervention (p < 0.05); POMS score for tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, and anger-hostility significantly lower (p < 0.05) during bathing intervention. | GA: Karadakara, Japan TWC: 40 °C warm water bath | [35] |

| Terminal stage cancer | Group I (n = 24) One rejected; three did not receive mechanical bathing. Only 20 received mechanical bathing for 5 min using Marine Court SB7000. Assessment: 5 min duration. TM: patients took a cup of water before and after bathing to prevent dehydration. | Pilot study. 24 adults (>20 years old) in terminal cancer stage. | Patients’ state of anxiety assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | 16 patients out of 23 showed significant reduction in the anxiety as evaluated by STAI (p < 0.0001) after mechanical bathing. Most patients felt comfortable and relaxed in their verbal responses post-bathing. Thus, safe, and pain-relieving for patients in the terminal stage cancer. | GA: Kyoto, Japan TWC: 41 °C water bath. | [36] |

| Depression | Group I (n = 17): hyperthermic bath alone. Group II (n = 19): sham condition. Group I received 2 hyperthermic baths per week for 4 w or a sham/placebo group with green light. Assessment: baseline, 2 w, 4 w (follow-up). TM: no changes in antidepressant treatment allowed during the study period. | Single-site, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial of hyperthermic bath vs sham-placebo (green light) 36 patients. | Outcome was measured using the 17-item Hamilton Scale for Depression (HAM-D)Total Score from baseline to 2 w time point. | At week 2: Group I showed significant (p = 0.037) difference in the change in HAM-DTotal Score 3.14 points after 4 interventions suggesting the efficacy of hyperthermic bath in depressed patients. | GA: Freiburg, Germany TWC: 40 °C water bath. | [37] |

| Stress response and psychological state | Group I (n = 78): moor bath alone. 78 participants received a total of seven moor applications for 20 min each followed by 20 min resting period. Assessment: baseline, 1w, 3 w. TM: no additional. | Randomized controlled pilot study. 78 patients. | Salivary cortisol level, blood pressure and heart rate were measured before and after moor bath. Mood state in participants was measured using the German version of the multidimensional Mood State Questionnaire (MDBF). | 61.5% of patients showed significant reduction in cortisol level between pre- and post-moor bath in week 1 (p < 0.008); and in 46.2% of participants between pre- and post-moor bath in week 3 was non-significant (p< 0.1617). Blood pressure was after moor bath. Heart rate increased during moor bath but was significantly lower in week 3 compared to week 1. Mood state significant improved after both moor baths. | GA: Bavaria, Germany TWC: 42 °C moor bath. | [38] |

| Mental stress, sleep disorder, and general health problems. | Group I (n = 223): hot spring balneotherapy alone. Group II (n = 139): did not receive hot spring balneotherapy. Group I received head-out immersion hot spring balneotherapy of 30 min for at least 1–3 times a week for 5 months. Assessment: baseline, 3 months. TM: no additional. | Randomized clinical trial. 362 sub-healthy participants (age group: 18–65 years old) | Mental and physical state were examined using two sets of self-designed questionnaires in the health examination center. | Sleep disorder (difficulty in falling asleep (p = 0.017); dreaminess, nightmare suffering, and restless sleep (p = 0.013); easy awakening (p = 0.003) and difficulty in falling into sleep again after awakening (p = 0.016); and mental stress (p = 0.031) and problems of general health (head pain (p = 0.026), joint pain (p = 0.009), leg or foot cramps (p = 0.001), blurred vision (p = 0.009)) were relieved significantly in Group I compared to control (Group II). Relief of insomnia, fatigue, and leg or foot cramps was greater in old-age group than in young age-age group (p < 0.05). Waist circumference was significantly in women below age of 55 years (p < 0.05) but not in men. | GA: Chongqing, China. TWC: 36–42 °C rich in SO42–, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl, metaboric acid, fluorine, and Sr. | [39] |

| Distress and health risk. | Group I (n = 65): geothermal water group. Group II (n = 65): control group. Group I received balneotherapy for 5 days a week over a 2 weeks period. Control group did not receive therapy. Assessment: baseline, 2 w. No follow-ups. TM: no additional. | Open label randomized controlled trial. 130 male seafarers aged between 25 and 64 y. | Severity of distress symptoms and health risk change post-balneotherapy was measured using self-assessment scale General Symptoms Distress Scale (GSDS). | After week 2, Group I experienced significant reduction in the number of stressed symptoms (p < 0.001) or 60%, intensity of stress symptoms by 41% and stress management improved by 32%. Probability of general health risk decreased by 18% (p = 0.01). | GA: Klaipeda, Lithuania. TWC: 34.6 °C rich in Na+, Cl−, SO42−, Ca2+, Mg2+. | [40] |

| Stress and fatigue | Group I (n = 65): Geothermal group. Group II (n = 50): music group. Group III (n = 65): Control group. Group I received a head-out immersion balneotherapy sessions for 15 min daily, five times a week, for 2 weeks. Group II received music therapy for 20 min Assessment: baseline, w. TM: no additional. | Prospective open label randomized controlled parallel group biomedical trial. 180 male seamen (25–64 years of age group) with stress and fatigue level more than 2 (VAS from 0 to 10). | Stress and fatigue outcomes were assessed using the self-administered general symptoms distress scale (GSDS), the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), and the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ). | After week 2, Group I (geothermal group) showed a significant therapeutic response compared to music and control groups including significant positive changes in CFQ, mood, and pain (p < 0.001). Balneotherapy treatment showed significant reduction in the blood pressure (p = 0.004), respiratory rate (p = 0.001), while music therapy showed significant reduction in respiratory rate (p = 0.009) with significance differences among groups (p < 0.001). Only geothermal group showed significant less medication use (p = 0.047). | GA: Klaipeda, Lithuania. TWC: 34.6 °C rich in Na+, Cl−, SO42−, Ca2+, Mg2+. | [41] |

| Knee osteoarthritis (Report 2) | Group I (n = 25): consecutive treatment group. Group II (n = 25): intermittent treatment group. Group I received total of 10 consecutive treatment sessions for 2 weeks (5 days/week), While Group II received total of 10 intermittent treatment sessions for 5 weeks (two times/week). Tap water bath was given for 20 min during treatment sessions followed by 30 min rest and then 2-cm thick local peloid packs (45 °C) was applied on knee. Assessment: baseline, 2 w, 5 w, 12 w post-treatment. TM: no additional. | Randomized double-blind clinical trial. 50 patients. | Degree of pain was assessed using VAS, well-being of patients (pain, stiffness, and physical functions) using Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), quality of life (QoL) using SF-36. | Both consecutive and intermittent balneological treatment regimens of knee osteoarthritis showed statistically significant clinical effects as well as effects on the QoL till 3 months (similar efficacy). After 3 months, joint stiffness (WOMAC), role-emotional (SF-36), and vitality (SF-36) in group 1 and for mental health (SF-36) in both groups became non-significant. | GA: France TWC: mineral water (38 °C); peloid (Pelomin) 45 °C. | [42] |

| Mastalgia | Group I (n = 20): balneotherapy plus conventional treatment of mastalgia program. Group II (n = 20): Conventional treatment of mastalgia program alone. Both groups received conventional treatment for six weeks. Group I received a total of 10 sessions of balneotherapy during last two weeks. Assessment: baseline, 6 w. TM: Conventional treatment included reassurance regarding the absence of breast cancer, refraining from methylxanthine containing foods and beverages, use of a sports brassiere and paracetamol (maximum daily dose of 1000 mg) were recommended for both groups for 6 weeks. No additional. | Assessor-blinded randomized controlled clinical study. 40 female mastalgia patients. | Mastalgia was assessed using the Breast pain questionnaire (BPQ), QoL was assessed using the Turkish version of the Short Form-36 (SF-36). Serum level of cytokines was measured using ELISA kits. | At week 6, balneotherapy group showed significant improvement in total BPS (p = 0.001), VAS (p = 0.039), present pain intensity (PPI) (p = 0.004). Significant decrease in the cytokine TNF-µ level (p = 0.003) in balneotherapy group. | GA: Haymana, Turkey. TWC: 44 °C rich in Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3−, F−, chrome, Cu2+, Zn2+. | [43] |

| Chronic pelvic pain. | 16 patients received 10 heated seawater baths for 20 min followed by application of 10 mud-pack applications for 10 min on pelvic area in the morning and afternoon at fixed time for five days. Assessment: baseline, 5 d, 1 month (Follow-up). TM: patients were allowed to continue with previously prescribed pain medication. | Open, prospective pilot study. 16 patients with Chronic pelvic pain (20–75 years age group) | VAS for pain, the Cleveland Clinic Constipation Score (CCCS), the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS), the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and SF-36 were measured thrice: before, immediately after treatment and at the end of one-month post-treatment. | Significant improvement in almost all score after balneotherapy—VAS (p = 0.003), CCCS (p = 0.203), OABSS (p = 0.049), FSFI (p = 0.441), SF-36 (pain, p = 0.008); social functioning, p = 0.008; role limitations due to emotional problem, p = 0.002; emotional wellbeing, p = 0.012; physical functioning, p = 0.013). | GA: Wando Island, Republic of Korea. TWC: sea water pool (38 °C) and mud pack (40 °C) rich in Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, and Na+. | [44] |

| Fibromyalgia. | Group I (n = 50): balneotherapy alone. Group II (n = 50): tape water alone. Group I received balneotherapy with Vetriolo’s water and Group II (control group) received heated tape water for 15 min daily immersion (6 times/week) for two consecutive weeks. Assessment: baseline, 2 w, 3 months, 6 months. TM: both groups given pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. | Prospective randomized, controlled, parallel group, double-blind trial. 100 patients. | The primary outcome measurements—change of global pain using VAS, and Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire total score (FIQ-Total) from baseline to 15 days. Secondary outcome measurement—using Widespread Pain Index (WPI), Symptom Severity Scale Score (SS score), Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). | At week 2, VAS in the balneotherapy (BT) group, was significant (p < 0.0001) reduced and persisted at 3-and 6-month follow-up. VAS was non-significant in control group. FIQ total score in the BT group improved significantly after 2 weeks (p < 0.001) and persisted significantly until 6 months (p < 0.0001). significant reduction in WPI in BT group after week 2 and persisted until 6 months—p < 0.0001. in control group—p < 0.05. SS score in BT group—p < 0.05–0.0001 until 6 months. Significant improvement of SF-12 MCS and CES-D in BT group—p < 0.01 and persisted until 6 months follow-up (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.05 respectively). | GA: Trento, Italy. TWC: 36 °C rich in SO42−, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Fe2+. | [45] |

| Osteoarthritis | Group I (n = 26): jet massage treatment in thermal water. Group II (n = 24): jet massage treatment in tap water. Treatment include 30 min session for 5 days in a week for 3 weeks (total 15 treatments). Assessment: baseline, 3 w, 3 months. TM: no additional. | Randomized double-blind controlled study. 50 osteoarthritis patients (50–75 years age group) | Severity of pain using VAS, well-being of patients (pain, stiffness, and physical functions) using Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), quality of life (QoL) using SF-36 were determined before first treatment, after last treatment and 3 months after the last treatment. | Group I (treatment group) showed significant improvement in all scores compared to control group II: VAS in Group at 3 w and 3 months both significant—p < 0.001 and p < 0.008 respectively. Group II showed reduced pain only at 3 w—p < 0.006. WOMAC score in Group I was significant at both 3W and 3 months: activity—p < 0.001, stiffness—p = 0.004, pain—p = 0.002 (at 3 w); activity—p < 0.001 (at 3 months). SF-36—significant improvement in vigorous activities in Group I (p = 0.005). | GA: Szigetvar, Hungary. TWC: 34 °C rich in SO42−, Na+, Cl−, HCO3−, and H2SiO3. | [46] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Group I (n = 25): balneotherapy plus standard drug treatment. Group II (n = 25): standard drug treatment alone. Group I received 12 balneotherapy sessions of 20 min (6 days/week excluding Sunday) for 2 weeks. Assessment: baseline, 2 w. TM: Both groups continued their previous stable drug regimen (conventional DMARD including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, or sulfasalazine; glucocorticoids). Patients were allowed to continue their NSAIDs whenever needed. | Single-blind randomized controlled trial. 50 patients (>18 years of age) | Severity of pain using VAS, functional disability status using Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI), rheumatoid disease activity using Disease Activity Score for 28-joints of 4 variables erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-4[ESR]), Oxidative status using parameters viz. MDA, NSSA, AOP, and SOD were determined at baseline and after the treatment (2 w). | Group I (treatment group) showed significant improvement in all parameters: VAS pain score—reduced significantly (p = 0.004); HAQ-DI function score—improved significantly (p = 0.037); DAS28-4[ESR] disease activity (p = 0.044); swollen joint count (p = 0.009). Antioxidant effects—NSSA level increased significantly (p = 0.003) but not in control group. | GA: Istanbul, Turkey. TWC: 36–37 °C rich in SO42–, Na+, Cl–, HCO3–, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and H2SiO3 (major constituents). | [47] |

| Chronic low back pain. | Group I (n = 52): thermal mineral water treatment plus usual musculoskeletal pain killer treatment. Group II (n = 53): traditional musculoskeletal pain killer treatment alone. Group I received 15 sessions of balneotherapy treatment for 20 min/session for 3 weeks. Assessment: baseline, 3 w, 9 w (follow-up). TM: usual musculoskeletal painkiller treatment. | Randomized, controlled follow-up study. 105 patients (18–75 years age group). | Severity of pain using VAS score, functional disability using the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), and the quality of life using the EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D) were determined before, right after, and 9 weeks after 3 weeks therapy. | VAS score of existing low back pain at rest decreased significantly in Group I (p <0.001) after 3 weeks balneotherapy and persisted in the follow-up period. ODI improved significantly in Group I (p < 0.001); EuroQol-5D index on QoL improved significantly (p < 0.001); EuroQoL-VAS showed improvement in the current state of health (p < 0.001). Number of patients requiring NSAIDs, opioids, muscle relaxants, and paracetamol for low back pain decreased after balneotherapy treatment. | GA: Budapest, Hungary. TWC: 38 °C rich in Ca2+, Mg2+, and HCO3–. | [48] |

| Obesity with knee osteoarthritis | Group I (n = 10): received hydrokinesitherapy with salsobromoiodic water. Group II (n = 10): did not receive intervention. Group I received treatment of two sessions per week for 8 consecutive weeks. Assessment: baseline, 8 w, 6 months (follow-up). TM: no additional. | Follow-up study. 20 patients. | Severity of pain using VAS score, clinical knee evaluation using range of motion (ROM) and lower limb muscle strength, Italian validated versions of WOMAC and Lequesne Algofunctional Index were determined at baseline, after 8 weeks and 6 months after 8 weeks treatment. | At week 8: VAS score for pain reduced significantly in Group I (p = 0.0039) during walking in flat surface. At month 6: VAS core persisted significantly low (p = 0.00954). WOMAC score reduced significantly between baseline and week 8 (p = 0.0137), between baseline and 6 months (p = 0.006438). No significant improvement in kinetic path assessment. | GA: Padua, Italy. TWC: 38 °C rich in Na+, SO42−, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, K+, Br−, and HCO3− | [49] |

| Knee osteoarthritis (Report 3) | Group I (n =27): physical therapy alone. Group II (n = 19): balneotherapy plus physical therapy. Both groups received physical therapy including hot pack (20 min/day), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (20 min/day), and ultrasonography (5 min/day) for 5 days/week for total duration of 3 weeks. Group II received concomitant balneotherapy session lasting 20 min daily at the same timing (5 days/week) for 3 weeks. Assessment: baseline, 3 w. TM: NSAIDs not allowed during treatment period. | Controlled study. 46 patients (57–85 years age group) | Pain severity using VAS, pain, stiffness, and physical function using Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) determined before and after treatment. | Group II showed significant improvement in all parameters (all p values < 0.05) compared to control group which received only physical therapy. | GA: Ankara, Turkey. TWC: 38 °C rich in NaHCO3, F−, and Cl−. | [50] |

| Fibromyalgia. | Group I (n = 20): balneotherapy alone. Group II (n = 21): mud-bath treatment alone. Both groups received their respective treatment once daily for 6 days/week for 2 weeks. Mud was applied at a temperature of 47 °C for 10 min, and thermal immersion (38 °C) for 10 min daily. Assessment: baseline, 2 w, 12 w follow-up. TM: patients allowed to continue their usual pharmacological treatment. | Multidisciplinary approach study. 41 patients (31–69 years age group). | Pain severity using VAS, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), and SF-36 questionnaire for evaluation of QoL were measured at baseline, after treatment (week 2), and week 12 post-treatment. | Group II showed better outcome: Pain (VAS)—p < 0.05; FIQ—p < 0.05; SF-36 PR physical role—p < 0.05. Group I showed significant improvement in only pain VAS—p < 0.05. Rest were non-significant compared to group that received mud-bath alone. | GA: Montecatini, Italy. TWC: 38 °C rich in Na+, SO42−, and Mg2+. | [51] |

| Osteoarthritis of the hips and the knees. | Group I (n =26): mineral water group. Group II (n = 24): organic fraction group. Group III (n = 24): tap water group. Patients received a 30 min thermal water treatment in a bathtub, five times a week for 3 weeks. Assessment: baseline, 3 w, 3 months (Follow-up). TM: suspended analgesic medications during the 3-weeklong treatment. | Double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. 74 patients (mean age 67.3 ± 4.48 years) | Range of movement (ROM) of the involved joints, Western Ontario, and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), visual analog scale (VAS) for pain severity and Short Form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) were measure at baseline, after first treatment and at 3 months post-treatment as a follow-up. | Group II (organic fraction) showed significant improvement in all parameters compared to control group: ROM scores after 3 months (hip flexion p = 0.028, hip abduction p = 0.004, hip adduction p = 0.002, knee flexion and extension p < 0.001). WOMAC total score (p < 0.001). VAS pain reduction significant both at 3W (p < 0.001) and 3months (p = 0.025). SF-36 physical functioning—significant difference compared to tap water group (p = 0.02). Not significant different from mineral group in all parameters. | GA: Szigetvar, Hungary. TWC: 34 °C, mineral composition not defined. | [52] |

| Psoriasis (Report 1) | Group I (n = 80). All patients received 3 week-long inward balneotherapy-based rehabilitation. Assessment: baseline, 3 w. TM: Total of 13 out of 80 patients received methotrexate, and another 5 patients received biological therapy. | Multidisciplinary approach study. 80 patients (mean age 63.7 ± 9.1) | Severity and extent of psoriasis were measured by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) highly sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured from venous blood samples before treatment and discharge. | Both PASI score and CRP levels showed improvement of psoriasis after balneotherapy-based rehabilitation. Methotrexate receiving patients had significantly lower PASI scores both on admission (p = 0.015) and before discharge (p = 0.031). | GA: Hungary. TWC: sulfuric water. | [53] |

| Psoriasis (Report 2) | Group I (n = 22): bathing in geothermal seawater plus UVB therapy (GSW+UVB). Group II (n = 22): Intensive treatment with geothermal seawater (IT-GSW). Group III (n = 24): UVB therapy alone (UVB). Group I received GSW+UVB three times/week for 6 weeks. Group II received IT-GSW for two weeks followed by NB-UVB therapy for 4 weeks. Group III received UVB three times/week for 6 weeks. Assessment: baseline, 6 w, 10 w. TM: no additional. | Randomized open multi-arm parallel Study. 68 patients (mean age in GSW group—41 ± 10.8 years; IT-GSW group—42.2 ± 16 years; UVB group—37.9 ± 14.4 y) | Severity and extent of psoriasis were measured by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), disease status (clear of diseases/almost clear) using Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment score at week 6 and change from baseline in Dermatology Life quality Index (DLQI) at week 10. | At week 6, in Group I—68.1% patients achieved PASI value greater than 75 (PASI 75) and 18.2% achieved PASI 90 (p < 0.001). In Group II—73.1% achieved PASI 75, and 42.3% achieved PASI 90 (p < 0.001). In Group III—only 16.7% achieved PASI 75. Difference among groups was significant (p < 0.05). Lattice score—in Group I, 63.6% (p < 0.01) showed clear/almost clear; In Group II, 65% (p < 0.001) showed clear/almost clear; in Group III—only 17% (non-significant). At week 10, 40% in Group I and 46% in Group II achieved a DLQI score of 0 or 1 compared with 12% in Group III. | GA: Iceland TWC: 24 °C rich in Na+, Cl−, Ca2+, K+, SO42−, and Mg2+, SiO2, F−, CO2, and H2S. | [54] |

| Rhinitis. | Group I (n = 34): herb-infused steam bath. Group II (n = 34): steam bath without herbs. Both groups received treatment for 30 min 3 times a week for 4 consecutive weeks. Assessment: baseline, 1 w, 2 w, 3 w, 4 w. TM: no additional. | A single-blind randomized controlled trial. 68 patients (20–59 years age). | Allergic rhinitis symptoms (itchy nose, runny nose, sneezing, nasal congestion, and watery eyes) were measured using the VAS at week 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4; Quality of life was assessed using questionnaires from Clinical Practice Guideline of Thai Traditional Medicine at week 0 and 4. | Symptoms were significantly reduced in both groups at week 2, 3, and 4, but difference was not significant between two treatment methods. Patients’ satisfaction was significantly greater in Group I compared to control group (p < 0.05). | GA: Bangkok, Thailand. TWC: herb infused water. | [55] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wangchuk, P.; Yeshi, K.; Ugyen, K.; Dorji, J.; Wangdi, K.; Samten; Tshering, P.; Nugraha, A.S. Water-Based Therapies of Bhutan: Current Practices and the Recorded Clinical Evidence of Balneotherapy. Water 2021, 13, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010009

Wangchuk P, Yeshi K, Ugyen K, Dorji J, Wangdi K, Samten, Tshering P, Nugraha AS. Water-Based Therapies of Bhutan: Current Practices and the Recorded Clinical Evidence of Balneotherapy. Water. 2021; 13(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWangchuk, Phurpa, Karma Yeshi, Karma Ugyen, Jigme Dorji, Karma Wangdi, Samten, Phurba Tshering, and Ari Satia Nugraha. 2021. "Water-Based Therapies of Bhutan: Current Practices and the Recorded Clinical Evidence of Balneotherapy" Water 13, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010009

APA StyleWangchuk, P., Yeshi, K., Ugyen, K., Dorji, J., Wangdi, K., Samten, Tshering, P., & Nugraha, A. S. (2021). Water-Based Therapies of Bhutan: Current Practices and the Recorded Clinical Evidence of Balneotherapy. Water, 13(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13010009