Land Use and Water Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. History and Themes of the LuWQ Conference Series 2013–2021

- (a)

- to increase our knowledge about ‘system functions’, i.e., basic hydrogeological and biogeochemical processes and related tools and methodologies,

- (b)

- water quality monitoring which is about improving the effectiveness and increasing the added value of monitoring,

- (c)

- impact of weather variability and climate change on water quality.

- (d)

- assessing national or regional policy, e.g., with regard to the effectiveness of programmes of measures on water quality,

- (e)

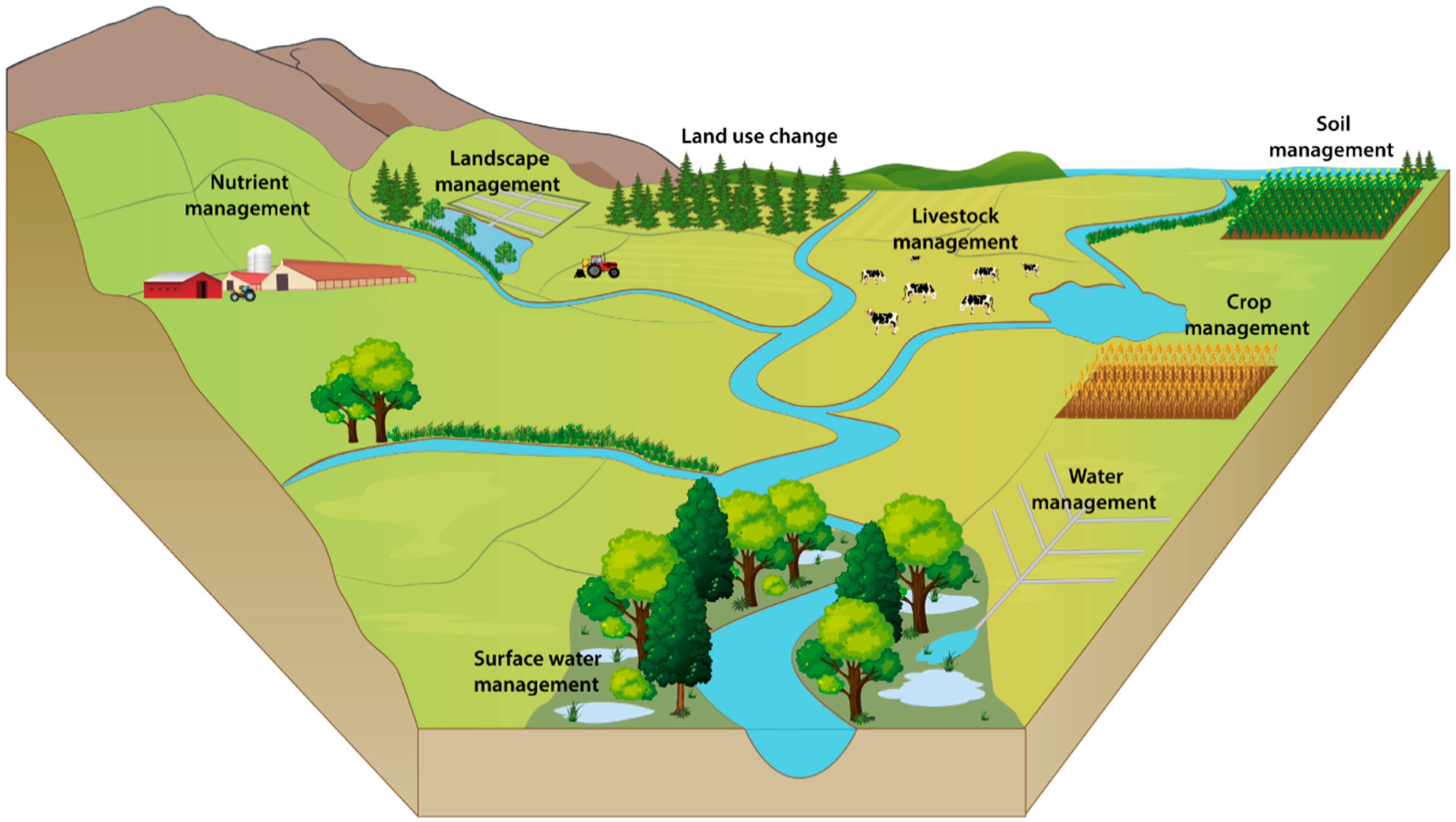

- improving water quality by farm management practices (monitoring and modelling) and changes in land use,

- (f)

- improving water quality by establishing eco-technological mitigation measures and discussing development, testing, implementation and operation to quantify the effects of such measures.

- (g)

- managing protected areas for water supply and nature conservation including risk assessment techniques, monitoring and modelling,

- (h)

- decision-making on Programmes of Measures with topics which look into the role of stakeholder input and science in policy decision-making, and

- (i)

- implementation of Programmes of Measures that focusses on social and economic incentives and regulatory mandates that drive implementation (carrots and sticks).

3. Contributions

3.1. Nitrogen Surplus

3.2. Protection of Groundwater from Pollution

3.3. Nutrient Sources and Dynamics in Catchments

3.4. New Technologies for Monitoring, Mapping and Analysing Water Quality

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tilman, D.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature 2002, 418, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erisman, J.W.; Sutton, M.A.; Galloway, J.; Klimont, Z.; Winiwarter, W. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.S.; Schjoerring, J.K.; van der Hoek, K.W.; Damgaard-Poulsen, H.; Zevenbergen, J.F.; Pallière, C.; Lammel, J.; Brentrup, F.; Jongbloed, A.W.; Willems, J.; et al. Benefits of nitrogen for food fibre and industrial production. In The European Nitrogen Assessment; Sutton, M.A., Howard, C.M., Erisman, J.W., Billen, G., Bleeker, A., Grennfelt, P., van Grinsven, H., Grizzetti, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbink, R.; Hicks, K.; Galloway, J.N.; Spranger, T.; Alkemade, R.; Ashmore, M.; Bustamante, M.; Cinderby, S.; Davidson, E.A.; Dentener, F.; et al. Global assessment of nitrogen deposition effects on terrestrial plant diversity: A synthesis. Ecol. Appl. 2010, 20, 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, D.; Houser, J.; Preiss, E.; White, O.; Fang, H.; Mesnick, L.; Barsky, T.; Tariche, S.; Schreck, J.; Alpert, S. Water resources: Agriculture, the environment, and society source. BioScience 1997, 47, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peierls, B.L.; Caraco, N.F.; Pace, M.L.; Cole, J.J. Human influence on river nitrogen. Nature 1991, 350, 386–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A.R.; Howarth, R.W.; Bazzaz, F.A.; Booth, M.S.; Cleveland, C.C.; Collinge, S.K.; Dobson, A.P.; Epstein, P.R.; Holland, E.A.; Keeney, D.R.; et al. Human health effects of a changing global nitrogen cycle. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, W.V.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Hassan, R.; et al. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: Ecosystems and Human WellBeing: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Billen, G.; Silvestre, M.; Grizzetti, B.; Leip, A.; Garnier, J.; Voss, M.; Howarth, R.W.; Bouraoui, F.; Lepistö, L.; Kortelainen, P.; et al. Nitrogen flows from European watersheds to coastal marine waters. In The European Nitrogen Assessment; Sutton, M.A., Howard, C.M., Erisman, J.W., Billen, G., Bleeker, A., Grennfelt, P., van Grinsven, H., Grizzetti, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, J.T.; Sharpley, A.N. Phosphorus: Agriculture and the Environment; Book Series: Agronomy Monographs; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.; Crop Science Society of America, Inc.; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2005; Volume 46, p. 1121. ISBN 9780891181576. Online ISBN 9780891182696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.H. On the fate of anthropogenic nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 104, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voß, M.; Baker, A.; Bange, H.W.; Conley, D.; Cornell, S.; Deutsch, B.; Engel, A.; Ganeshram, R.; Garnier, J.; Heiskanen, A.-S.; et al. Nitrogen processes in coastal and marine systems. In The European Nitrogen Assessment; Sutton, M.A., Howard, C.M., Erisman, J.W., Billen, G., Bleeker, A., Grennfelt, P., van Grinsven, H., Grizzetti, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive of the Council of December 12, 1991 Concerning the Protection of Waters against Pollution Caused by Nitrates from Agricultural Sources (91/676/EEC); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1991; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 Establishing a Framework for the Community Action in the Field of Water Policy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2000; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Directive 2006/118/EC on the protection of groundwater against pollution and deterioration Directive 2006/118/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 372, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Schoumans, O.F.; Chardon, W.J.; Bechmann, M.E.; Gascuel-Odoux, C.; Hofman, G.; Kronvang, B.; Rubæk, G.H.; Ulén, B.; Dorioz, J.-M. Mitigation options to reduce phosphorus losses from the agricultural sector and improve surface water quality: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 15, 468–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechmann, M.; Gascuel-Odoux, C.; Hofman, G.; Kronvang, B.; Litaor, M.I.; Lo Porto, P.A.; Newell-Price, G.R. Mitigation Options for Reducing Nutrient Emissions from Agriculture. A Study Amongst European Member States of Cost Action 869; Schoumans, O.F., Chardon, W.J., Eds.; Wageningen, Alterra, Alterra-Report 2141; 2011; p. 144. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254832937_Mitigation_options_for_reducing_nutrient_emissions_from_agriculture_a_study_amongst_European_member_states_of_Cost_action_869 (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Hoffmann, C.C.; Zak, D.; Kronvang, B.; Kjaergaard, C.; Carstensen, M.V.; Audet, J. An overview of nutrient transport mitigation measures for improvement of water quality in Denmark. Ecol. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, M.V.; Hashemi, F.; Hoffmann, C.C.; Zak, D.; Audet, J.; Kronvang, B. Efficiency of mitigation measures targeting nutrient losses from agricultural drainage systems: A review. Ambio 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgaard, T.; Hansen, B.; Hasler, B.; Hertel, O.; Hutchings, N.J.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Jensen, L.S.; Kronvang, B.; Olesen, J.E.; Schjoerring, J.K.; et al. Policies for agricultural nitrogen management—Trends, challenges and prospects for improved efficiency in Denmark. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Højberg, A.L.; Windolf, J.; Børgesen, C.D.; Troldborg, L.; Tornbjerg, H.; Blicher-Mathiesen, G.; Kronvang, B.; Thodsen, H.; Ernstsen, V. National nitrogen model, catchment model for loading and mitigation. In National Geological Survey for Denmark and Greenland Report; 2015; p. 111. ISBN 978-87-7871-417-6. (In Danish) [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H.E.; Kronvang, B. Modifying and evaluating a P index for Denmark. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2006, 174, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klages, S.; Heidecke, C.; Osterburg, B. The Impact of Agricultural Production and Policy on Water Quality during the Dry Year 2018, a Case Study from Germany. Water 2020, 12, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klages, S.; Heidecke, C.; Osterburg, B.; Bailey, J.; Calciu, I.; Casey, C.; Dalgaard, T.; Verloop, K.; Velthof, G. Nitrogen Surplus—A Unified Indicator for Water Pollution in Europe? Water 2020, 12, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendland, F.; Bergmann, S.; Eisele, M.; Gömann, H.; Herrmann, F.; Kreins, P.; Kunkel, R. Model-Based Analysis of Nitrate Concentration in the Leachate—The North Rhine-Westfalia Case Study, Germany. Water 2020, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, F.; Laursen, R.K.; Cassidy, R.; Farrow, L.; Tendler, L.; Williams, J.; Surdyk, N.; Velthof, G. How Can Decision Support Tools Help Reduce Nitrate and Pesticide Pollution from Agriculture? A Literature Review and Practical Insights from the EU FAIRWAY Project. Water 2020, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyenola, G.; Graeber, D.; Meerhoff, M.; Jeppesen, E.; Teixeira-de Mello, F.; Vidal, N.; Fosalba, C.; Ovesen, N.B.; Gelbrecht, J.; Mazzeo, N.; et al. Influence of Farming Intensity and Climate on Lowland Stream Nitrogen. Water 2020, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Pueppke, S.G.; Pang, J.; Diao, Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Nitrogen Transport in the Qiandao Lake Basin, a Large Hilly Monsoon Basin of Southeastern China. Water 2020, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, P.; Tetzlaff, B.; Trepel, M.; Wendland, F. Implementing a Statewide Deficit Analysis for Inland Surface Waters According to the Water Framework Directive—An Exemplary Application on Phosphorus Pollution in Schleswig-Holstein (Northern Germany). Water 2020, 12, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, X.; Shao, G.; Hu, T. Effects of Land Use on Stream Water Quality in the Rapidly Urbanized Areas: A Multiscale Analysis. Water 2020, 12, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fitch, P.; Thorburn, P.J. Predicting the Trend of Dissolved Oxygen Based on the kPCA-RNN Model. Water 2020, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, F.; Pohle, I.; Pullens, J.W.M.; Tornbjerg, H.; Kyllmar, K.; Marttila, H.; Lepistö, A.; Kløve, B.; Futter, M.; Kronvang, B. Conceptual Mini-catchment Typologies for Testing Dominant Controls of Nutrient Dynamics in Three Nordic Countries. Water 2020, 12, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Surdyk, N.; Møller, I.; Graversgaard, M.; Blicher-Mathiesen, G.; Henriot, A.; Dalgaard, T.; Hansen, B. Lag Time as an Indicator of the Link between Agricultural Pressure and Drinking Water Quality State. Water 2020, 12, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kronvang, B.; Wendland, F.; Kovar, K.; Fraters, D. Land Use and Water Quality. Water 2020, 12, 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092412

Kronvang B, Wendland F, Kovar K, Fraters D. Land Use and Water Quality. Water. 2020; 12(9):2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092412

Chicago/Turabian StyleKronvang, Brian, Frank Wendland, Karel Kovar, and Dico Fraters. 2020. "Land Use and Water Quality" Water 12, no. 9: 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092412

APA StyleKronvang, B., Wendland, F., Kovar, K., & Fraters, D. (2020). Land Use and Water Quality. Water, 12(9), 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12092412