1. Introduction

Salinization and sodification are major processes of soil degradation threatening land productivity and global food security [

1]. Salt-induced land degradation is common in arid and semi-arid regions, where rainfall is insufficient to maintain percolation of rainwater through the soil and irrigation is practiced without adequate drainage [

2]. The growing development of irrigated agriculture in arid and semi-arid lands has been essential for the food supply demanded by a growing world population. Over the last 50 years, the world’s net cultivated area has grown 12%, and in the same period, the global irrigated area has doubled [

3]. At present, about 20% of the world agricultural land is irrigated and this land produces 40% of the world food supply [

4]. Although the undisputable contribution of irrigation for the increase in food production, in areas where precipitation is scarce or irregular, irrigated agriculture can cause a disharmony with the nature of dry regions’ ecology, negatively affecting the quality of soils and water [

3,

5,

6,

7]. At present, it is estimated that more than 20% of the global irrigated area is affected by salinization caused by irrigation; in some countries, salt-affected soils occur in more than half of the irrigated land [

2]. In the Mediterranean area, 25% of irrigated cropland is affected by moderate-to-high salinization, leading to moderate soil degradation [

8], and adverse climatic conditions, like temperature increase and changes in the regional precipitation patterns, are likely to enhance the problem of salinization [

9,

10,

11,

12].

According to Rengasamy [

13], there are three types of salinity, based on the processes of salt accumulation: (i) groundwater-associated salinity, occurring in discharge areas of the landscape, where water tables are close to the surface and evaporation leads to the upward movement of water and salts; (ii) non-groundwater-associated salinity, that occurs in landscapes with deep water table and poor drainage, when salts introduced by rain, weathering, and aeolian deposits are stored within the soil

solum; and (iii) irrigation-associated salinity, when salts are introduced by irrigation water and accumulate within the root zone due to insufficient leaching. Certain factors lead to the acceleration of irrigation-induced salinity, like the poor-quality irrigation water, low hydraulic conductivity of soil layers, as found in heavy clay soils, and sodic soils, under high evaporative conditions.

Whether it is of natural genesis or induced by human activities, the progressive nature of salt-affected soils is a constraint for its early detection, and, although there are several reclamation techniques, the prevention of salt accumulation is more advisable than soil desalinization [

14,

15]. According to Eckelmann et al. [

16], the risk of salinization is defined as a measure of the probability and severity of the salinization/sodification due to human activities which adversely affects one or more soil functions. In agricultural regions, soil salinization varies widely, vertically, horizontally, and temporally, depending on conditions, such as the variation in soil texture, plant growth, irrigation water quality, hydraulic conductivity, and the irrigation system. In this sense, any risk assessment methodology must be based in meaningful indicators of soil and water quality, in order to assess whether or not a soil is potentially salt-affected [

17].

Risk assessment methodologies can be performed at different levels of scale and related levels of information detail, in each case using different types of approaches, namely, a qualitative, quantitative, or model approach [

17,

18]. Simulation models that deal with the dynamic and transient condition of soil salinity [

19,

20] can predict the effect of multiple scenarios (e.g., climatic variables, quality and quantity of irrigation water, fertilization rates, soil properties) on soil salinization, computing water and salt balances in the soil and leaching requirements, supporting the optimization of agricultural practices and land management [

19,

20,

21]. The complexity of some of these models, and the usual lack of input data, is a constraint to its application on large areas, and simple approaches are welcome to be used at national or regional scales [

18,

22]. Monitoring and assessment of soil salinity is decisive for effective adaptation and mitigation through land reclamation measures. At field level and at larger scales, mapping of salinity is required to establish the most appropriate irrigation and soil management practices, to delineate crop management zones, and for regional land management [

23].

The appropriate assessment methods are directly related to the spatial scale of interest [

22,

23]. In a continental scale, Tóth et al. [

24] generated a map of saline and sodic soils from the European Soil Database [

25], for the delineation of areas in the European Union that are threatened by salinization or sodification. For large spatial scales, the use of remote sensing (RS) or geographic information systems (GIS) techniques has been reported in several studies, frequently in combination with physically based models, aiming to extend their prediction capabilities (for e.g., [

15,

26,

27,

28]). According to Zhou et al. [

29], the use of risk indices or frameworks for soil salinity assessment may facilitate communication among scientists, policymakers, and practitioners by providing a basis for evaluating the environmental impact of agricultural practices and also government programs and policies. Frequently, these risk indices are GIS-based in order to ascertain priority areas, predict where it may occur in the future, and determine appropriate management options to mitigate salinity risk [

30]. One of the earliest indices for the assessment of soil salinity risk was the Salinity Risk Index (SRI), proposed by Eilers et al. [

31], later updated by Wiebe et al. [

32] to evaluate the salinization risk trends on the Canadian Prairies. The SRI was composed of five risk factors: the current presence and extent of salinity, topography, soil drainage, aridity, and land use [

31,

32]. A four-component risk assessment framework for salinity prevention was proposed by Grundy et al. [

33] for Queensland, Australia, where the components (current salinity stage, current land management, value of the assets under threat, and biophysical risk factors) interacted to give an overall salinity risk index. From this framework, Biggs et al. [

30] developed a GIS-based system to assess the risk of salinity in the Condamine basin, Australia. Zhou et al. [

29] presented a soil salinity risk assessment methodology by selecting a set of risk factors based on the conceptual Pressure–State–Response (PSR) sustainability framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [

34], where a set of fourteen risk factors were selected to develop a composite risk index for soil salinity in the Yinchuan Plain, China. Masoudi et al. [

35] proposed a model for risk analysis of soil salinization for the Payab Basin, Iran, using GIS with the overlay of hazard maps of nine indicators as the causes of soil salinity (depth of water table, soil texture, slope, irrigation water quality, groundwater quality, efficacy of surface geology, climate, aridity index, status of soil salinity) to obtain a final risk map. Specifically for irrigated lands, similar salinization risk assessment methodologies were developed, using GIS, and considering irrigation water quality, soil properties, and climate indicators [

15,

24]. These methodologies have a dominant focus on the prediction of the development of saline soils, and the assessment of the risk of soil sodicity alone has generally received less attention [

36]. Regardless of the modeling perspective or the soil deterioration problem to be predicted, the use of these integrated approaches evidenced its value for helping in decisionmaking regarding land resource management, allowing for the adoption of reclamation actions and the prediction of the spatial variation of irrigation-induced soil salinity and sodicity.

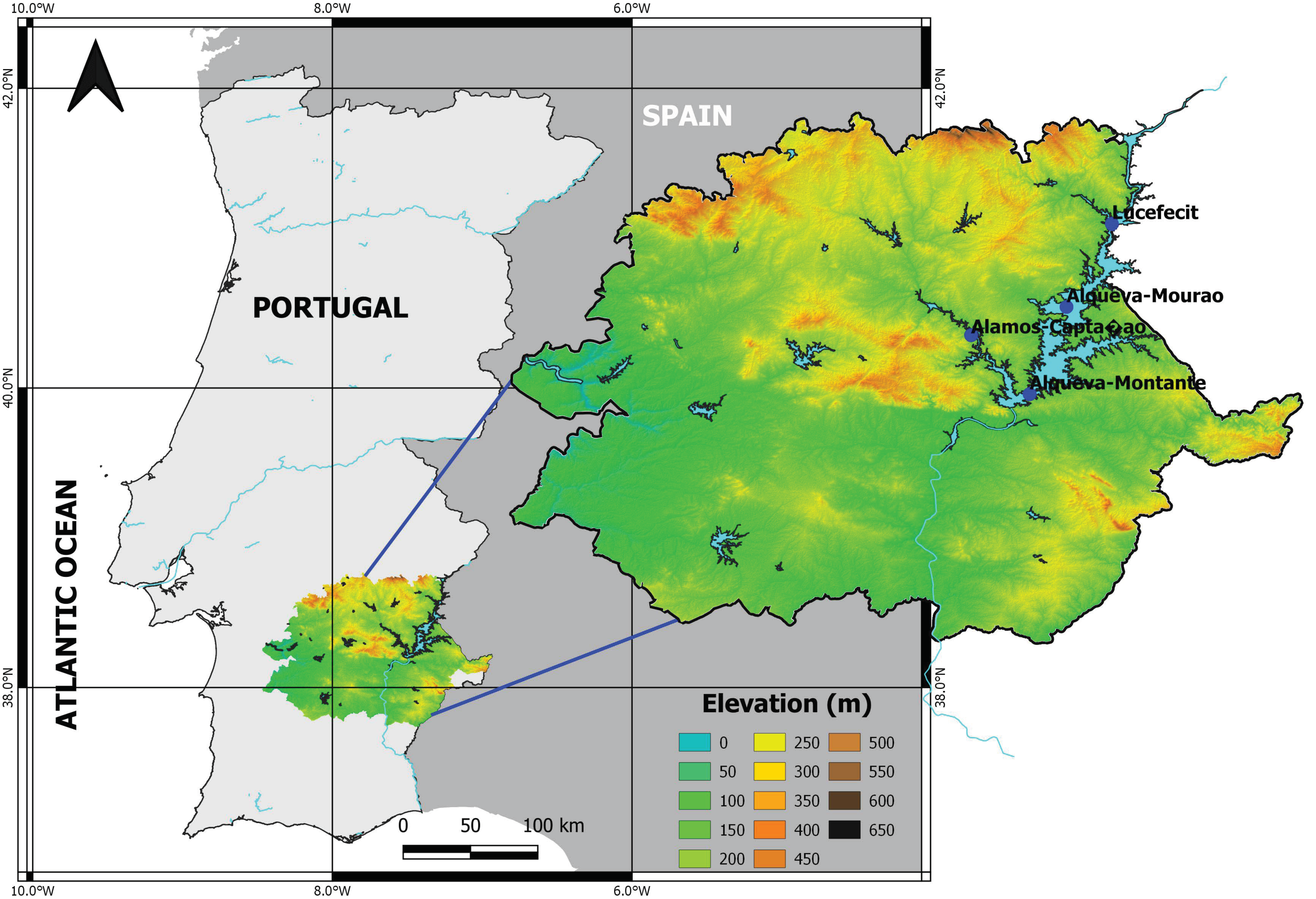

In this study, we aimed to: (i) present an overview of major criteria and respective indicators related with soil salinity and sodicity induced by irrigation; (ii) propose two composite risk indices, for soil salinization and soil sodification assessment in large areas, based on climate, irrigation water quality, soil information, and land-use data; (iii) present the risk indices when applied in a real scenario in a Mediterranean area in Southern Portugal.

2. Criteria and Indicators of Soil Salinization and Sodification

Indicators to predict soil salinization problems can be grouped following the common criteria for risk area identification according to soil threats [

16] (

Table 1), that considers a two-tiered approach, from a lower spatial resolution, less detailed and supported in available information, to a higher spatial resolution, requiring more detailed data and in situ measurements.

The most common soil salinity indicator is the electrical conductivity, usually measured in a saturation paste extract (ECe; dS m

−1). Yield reduction of many crops can occur for ECe > 4 dS m

−1, a condition that defines a saline soil [

37]. In saline soils, the large osmotic potential values on soil solution hinder plant transpiration, diminishing water availability to plants, which results in physiological deteriorations. Crop salt tolerance is the ability of plants to survive and produce profitable yields under the adverse conditions caused by soil salinity [

38]. Data of tolerance to salinity were first reported by Maas and Hoffman [

39] for numerous crops, by quantifying salt tolerance using the threshold (or breakpoint) model, that can be presented in terms of percentage of the maximum yield, known as the relative production function Equation (1):

where

Yr is the relative crop yield, with 100 being the maximum yield,

a is the threshold (breakpoint) salinity (dS m

−1), beyond which yield reduction will occur,

ECe is the salinity of saturated soil extract,

b is the slope, that represents the percentage of yield expected to be reduced for each unit of added salinity above the threshold salinity, and

c is the level of soil salinity (dS m

−1), above which the yield is zero. Values of

a and

b, and relative tolerance ratings for several crops, can be found in Maas and Grattan [

40], indicating, e.g., that while wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) or olive (

Olea europaea L.) are classified as moderately tolerant, grapevine (

Vitis vinifera L.), almond (

Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A. Webb) and a majority of vegetable crops are moderately sensitive to salinity, which increases the restrictions for their cultivation [

41] and the need for appropriate irrigation management measures for these crops [

42].

For sodic conditions, in addition to salinity diagnosis based upon ECe, the Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR) of the soil solution or of the irrigation water Equation (2) can be calculated [

38]:

where [Na

+], [Ca

2+], and [Mg

2+] are the concentrations (meq L

−1) in the saturated soil paste extract or in the irrigation water. A sodic soil presents a SAR value of 13 or higher. When ECe > 4 dS m

−1 and SAR > 13, the soil is classified as saline-sodic [

37]. In sodic soils, the high exchangeable sodium in the soil complex causes dispersion of its colloids, structural destruction, and aggregate failure, resulting in unfavorable physical properties, like low infiltration rate and low hydraulic conductivity [

9,

13]. When the salinity of the soil water is insufficient to counteract the negative effects of adsorbed Na

+ on soil structure, a “rainfall effect” [

43] can occur. More specifically, the leaching of salts by precipitation or excess irrigation water reduces the salinity of the soil solution, while the reduction in exchangeable Na

+ will be far smaller due to a buffer effect, performed by the exchangeable cations adsorbed in the soil matrix, causing, therefore, a reduction in the stabilizing effects of salinity on aggregate stability [

5,

22,

44]. When dry, sodic soils become denser and structureless since natural aggregation is destroyed. At the soil surface, dispersed clay particles can act as adhesive, forming relatively dense crusts that impede seedling rooting and emergence. The degree of crusting depends on soil texture, the mineralogy of the clay, the exchangeable sodium content, the energy of raindrop impact, and the rate of drying [

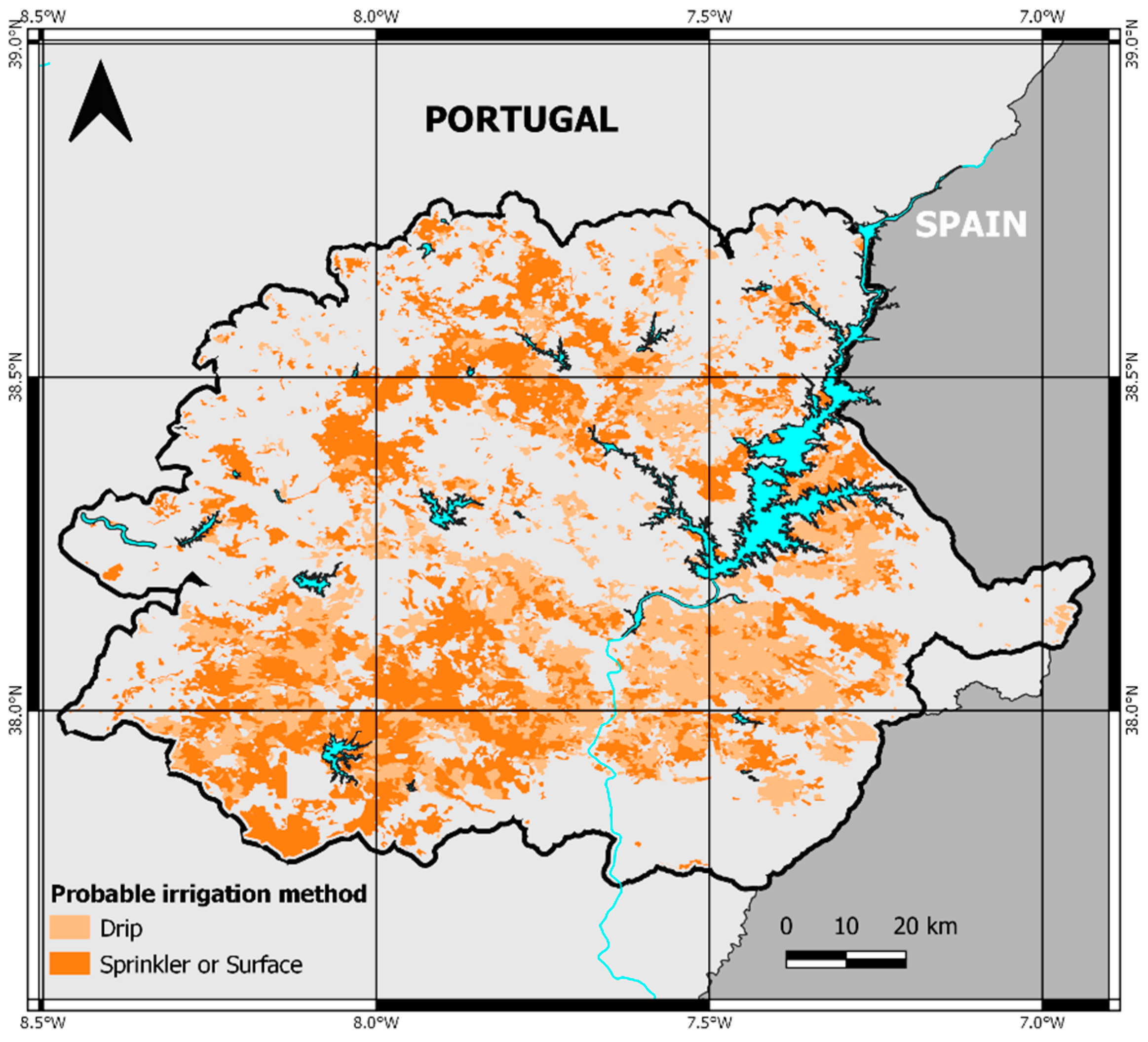

22]. At lower SAR levels, when chemical bonding is weakened, but no spontaneous dispersion takes place, inputs of energy are required for actual dispersion. While in drip irrigated fields this is hardly a problem, given the low flow rates of the drippers, the use of surface or sprinkler irrigation can increase the probability of soil structure degradation and surface crusting due to the physical disruption caused by runoff or by the water drops as they impact the soil surface aggregates [

45].

In addition to soils that are classified as saline or sodic due to their genesis conditions, like Solonchaks and Solonetz, there are other soils whose characteristics make them more susceptible to the development of secondary salinization. This is the case of poorly drained soils (soils with permanent or temporary water table close to the surface) or soils with unfavorable hydrophysical properties (low permeability, low porosity, fine-textured layers or horizons). A systematized list of saline or saline prone soils, according to the World Reference Base of Soil Resources [

46], was presented by Daliakopoulos et al. [

22] (

Table 2).

Many of the laboratory and field methods used to determine soil hydraulic properties are time-consuming, laborious, and limited to the sampling quantity and location, which restricts their use due to soil heterogeneity [

47,

48]. In fact, texture variability is one of the determining factors of this heterogeneity, and several methods have been proposed to establish a relation between soil texture and soil hydraulic properties [

47,

48,

49]. Following a methodology similar to de Paz et al. [

15], a classification of soil drainage can be made considering its relationship with textural classes (

Table 3). Drainage conditions are also affected by groundwater levels. Areas of low relief and particularly closed depressions encourage lateral translocation in surface and groundwater and salt accumulation [

50].

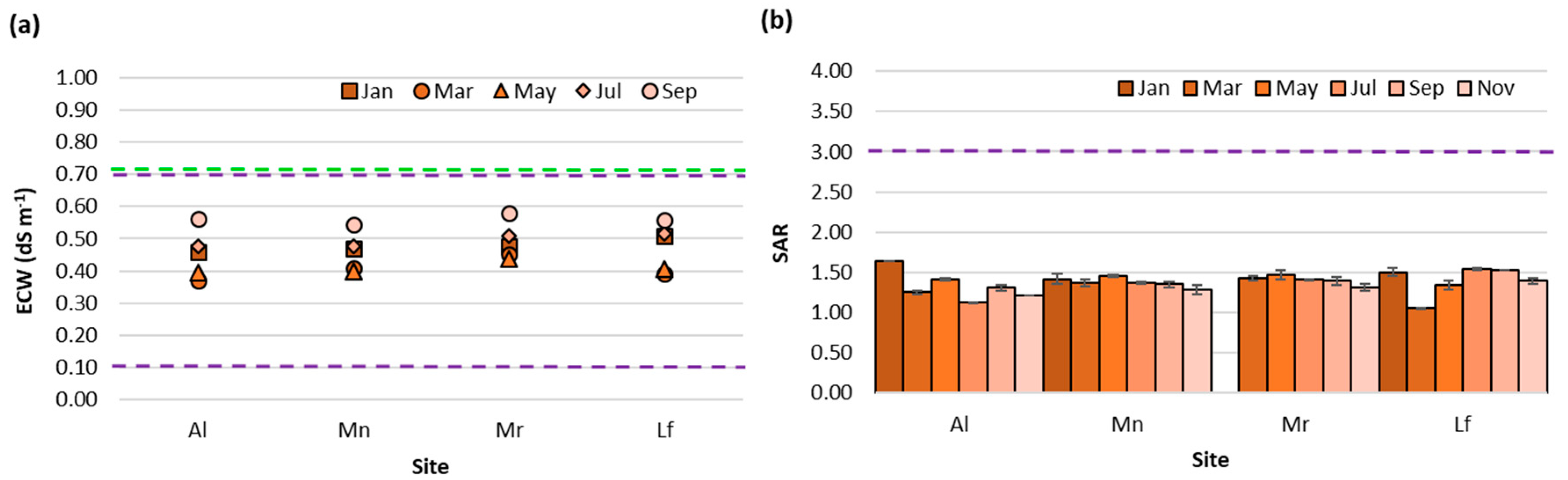

For the risk assessment of irrigation-induced salinization and sodification, the evaluation of irrigation water quality is of primary importance since it often constitutes the main source of salts. Some of the parameters used to evaluate soil salinization problems are the same that are used to evaluate the irrigation water quality, namely, electrical conductivity, in this case, Water Electrical Conductivity (ECW; dS m−1), Total Dissolved Salts (TDS; %), SAR, and the concentration of some specific ions that might cause toxicity to crops.

Although the suitability of a saline water for irrigation depends on different conditions of use, like crop, climate, soil, irrigation method, and management practices, only very tolerant crops can have satisfactory yields if irrigated with waters with EC that exceeds 10 dS m

−1. In fact, few normally used irrigation waters exceed EC of about 2 dS m

−1 [

51]. It is consensual the use of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) water quality guidelines for irrigation [

52], which considers three levels of restriction for the use of an irrigation water: none, slight to moderate, and severe. In these guidelines, salinity is assessed from EC

W, and sodicity (more specifically, infiltration rate of water in the soil) is assessed using EC

W and SAR together (

Table 4).

Irrigated agriculture develops primarily in areas where the interannual and seasonal quantity and distribution of precipitation and evapotranspiration are irregular. This leads to permanent (aridity) or temporary (drought) imbalances in water availability consisting in low average annual rainfall, with high spatial and temporal variability resulting in overall low moisture [

53]. These features contribute to unfavorable salt balances, which can be intensified by irrigation with poor-quality water [

54]. Climate plays a key role in the process and, whenever data are available, should be considered when defining a set of indicators for salinization/sodification risk prediction. A well-known indicator used as a numerical expression of dryness for climate classification and for the identification of regional patterns of aridity is the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) Aridity Index (AI) [

55], a mean accumulated annual precipitation/potential evapotranspiration ratio (P/PET). Considering the AI scale, the classification of climate types is hyper-arid (<0.05), arid (0.05–0.2), semi-arid (0.2–0.5), dry sub-humid (0.5–0.65), and humid (≥0.65). For dryland climate subtypes, AI values are below 0.65, and, according to Schofield and Kirkby [

50], values between 0.05 and 1 (arid to moist sub-humid) describe climatic conditions suitable for salinization to occur.

5. Conclusions

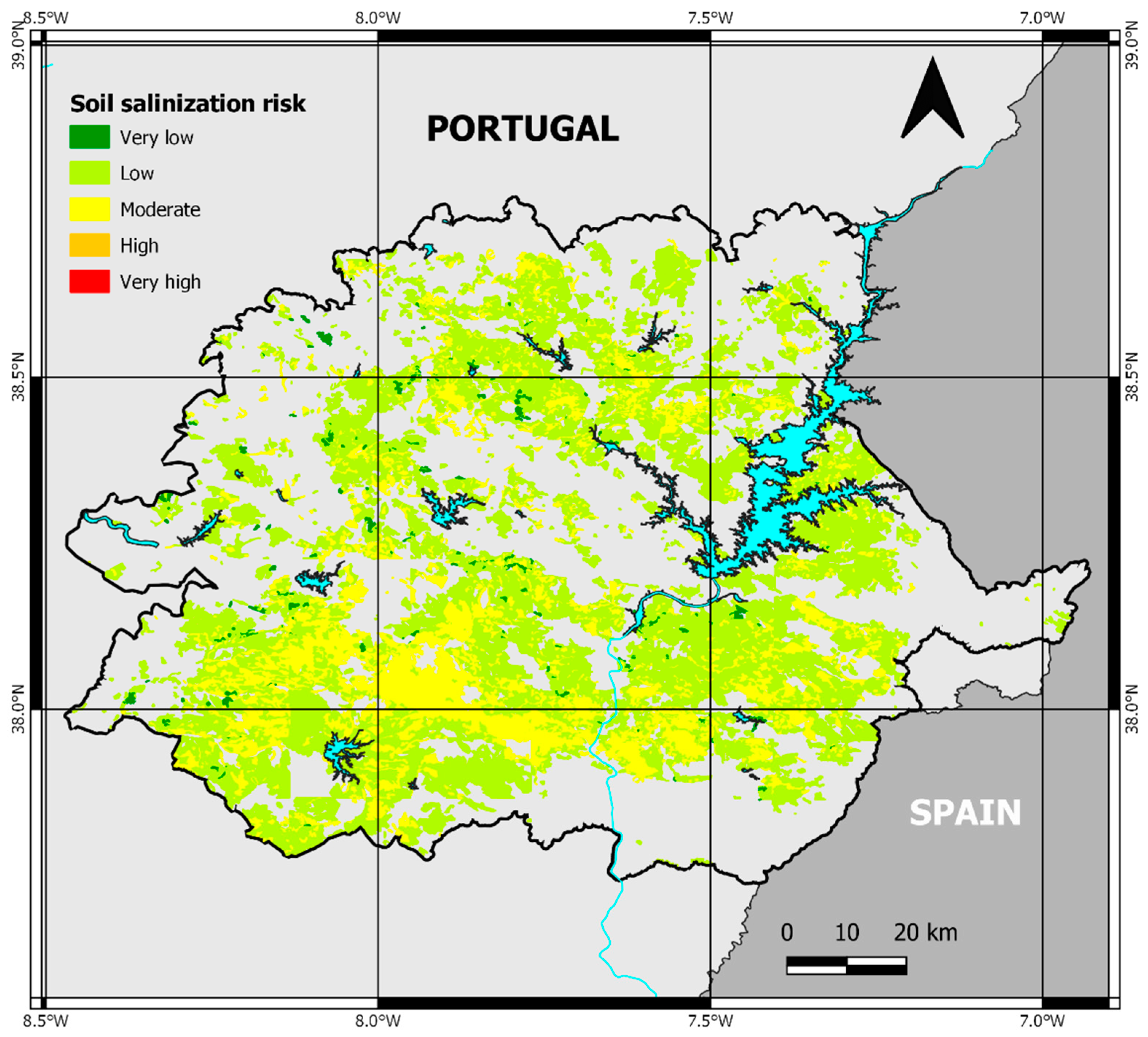

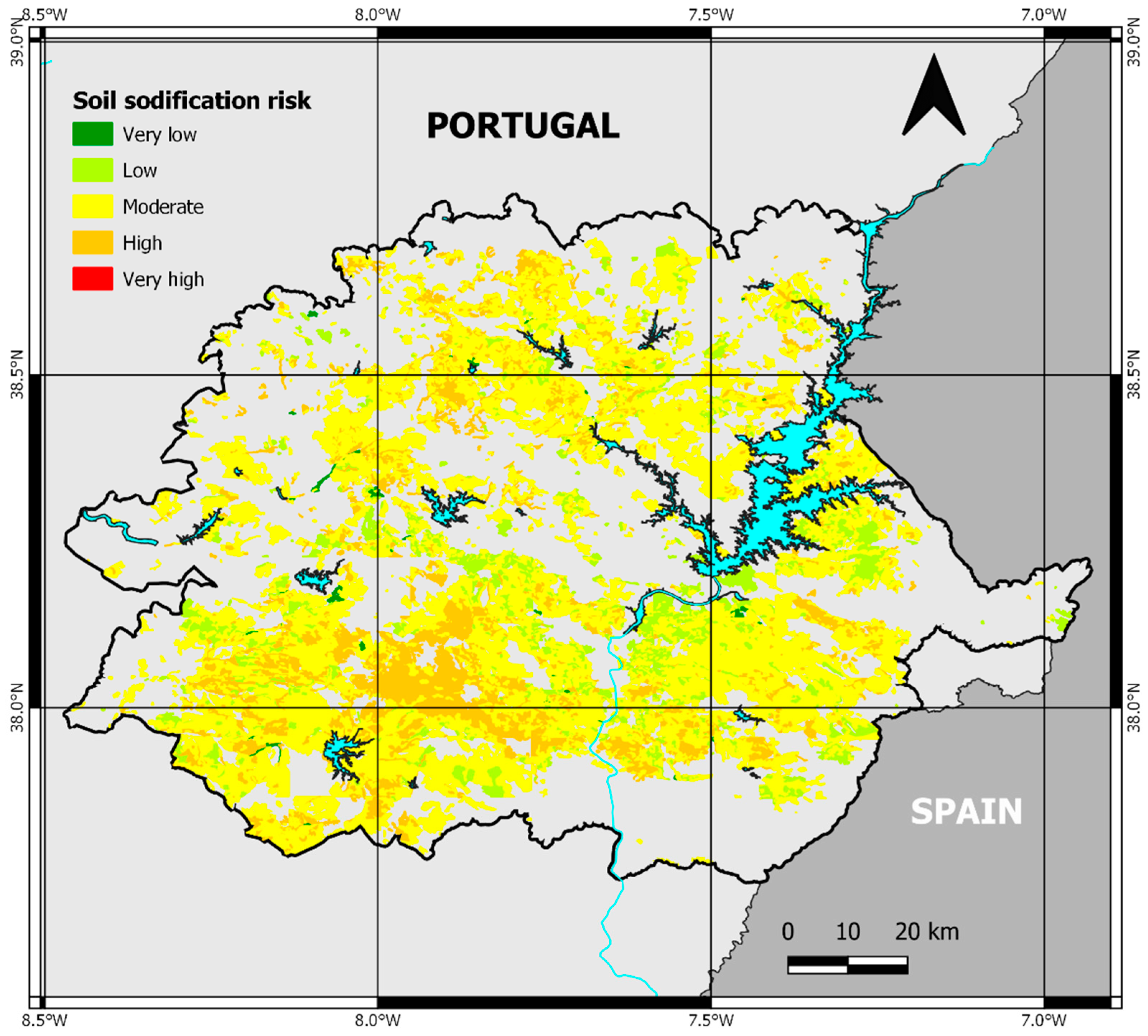

Negative impacts of soil salinity and sodicity in Mediterranean regions include decreased food production, deteriorating water quality in surface streams and groundwater, loss of biodiversity, and increased risk of flooding and desertification. The present study aimed to develop two risk indices for better prediction of soil salinity and sodicity in large areas, in order to provide farmers, rural planners, and resource managers with a tool to help identify susceptible areas, to apply appropriate agronomical strategies and management options and to avoid soil degradation in irrigated lands.

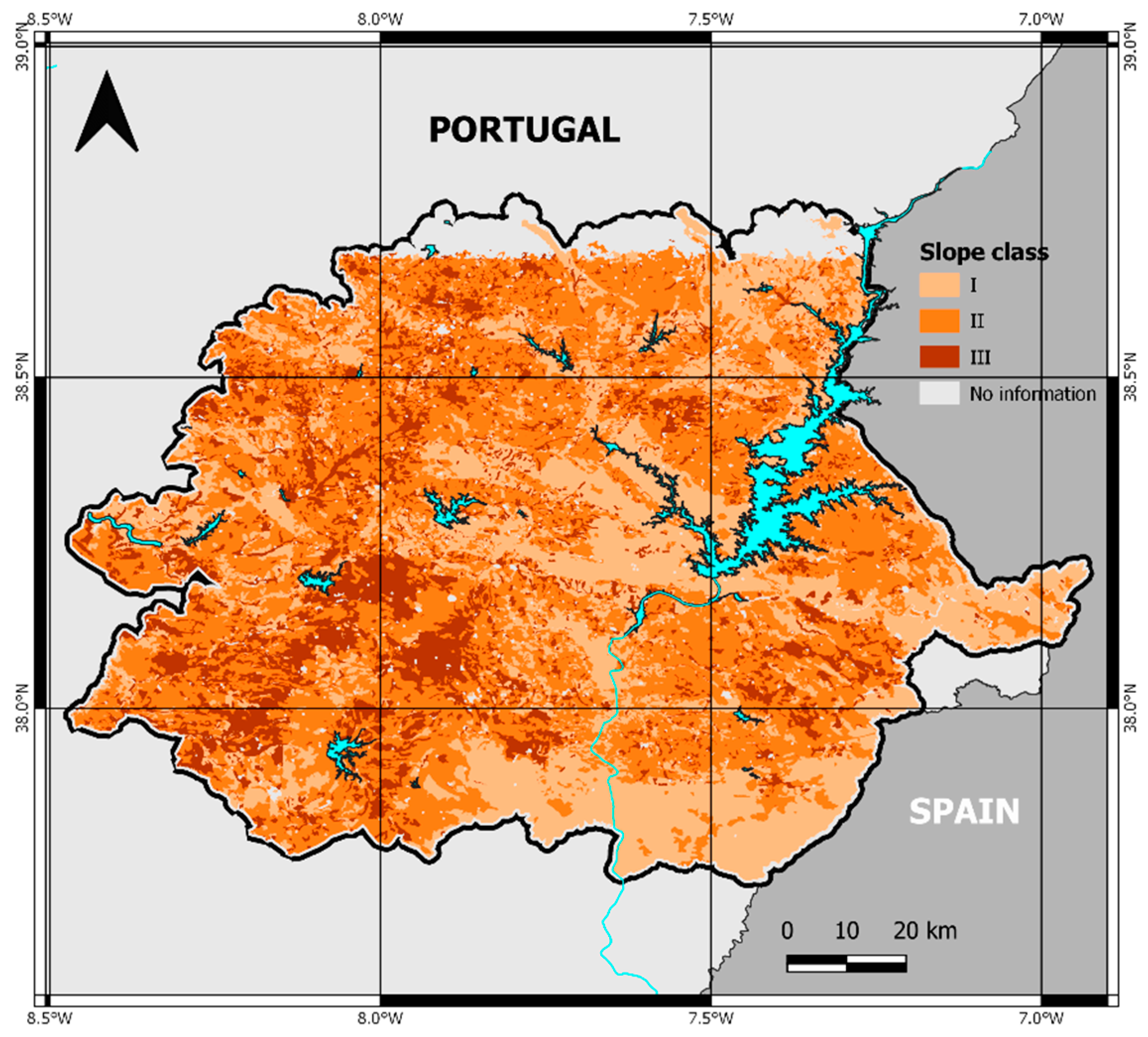

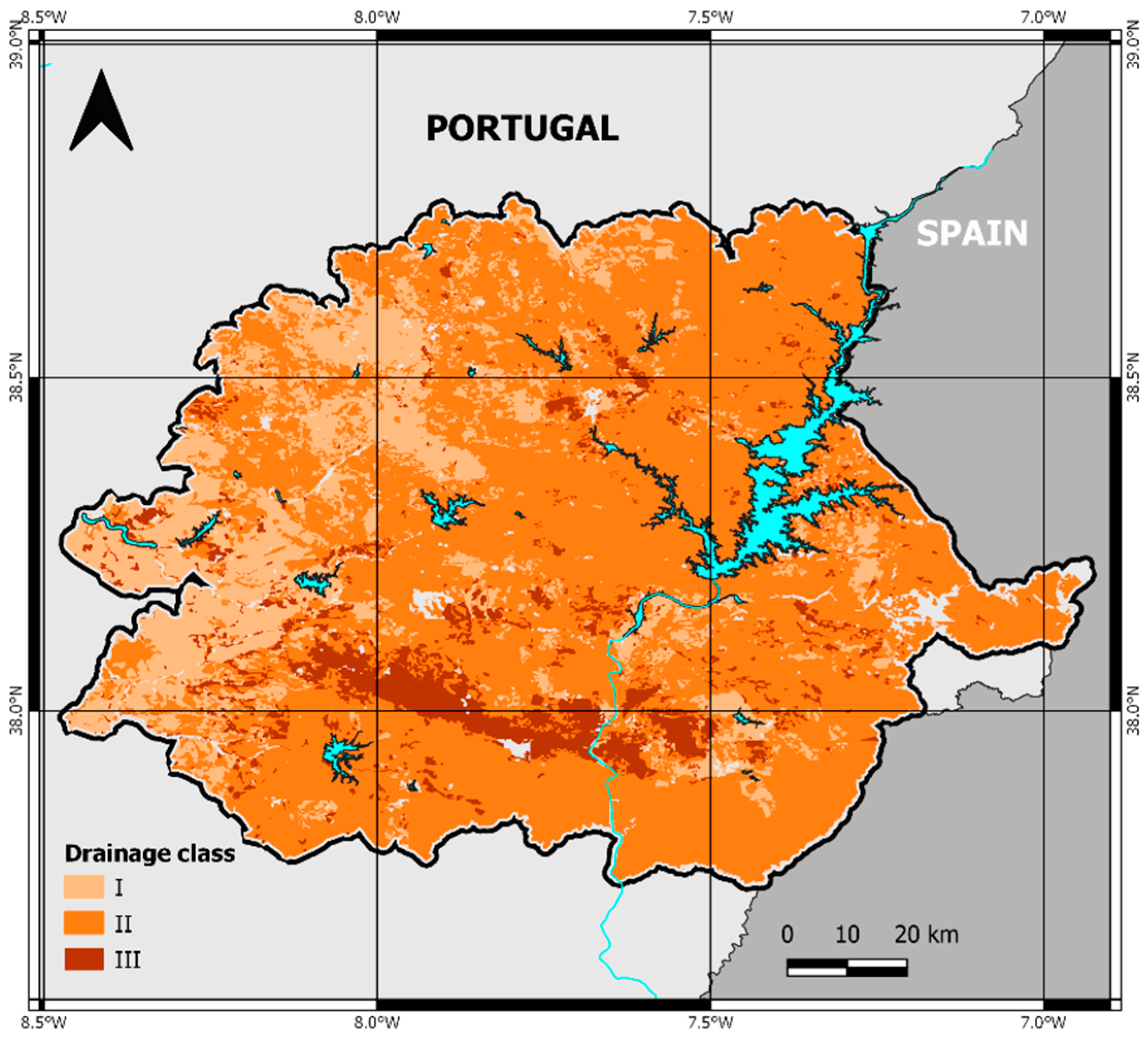

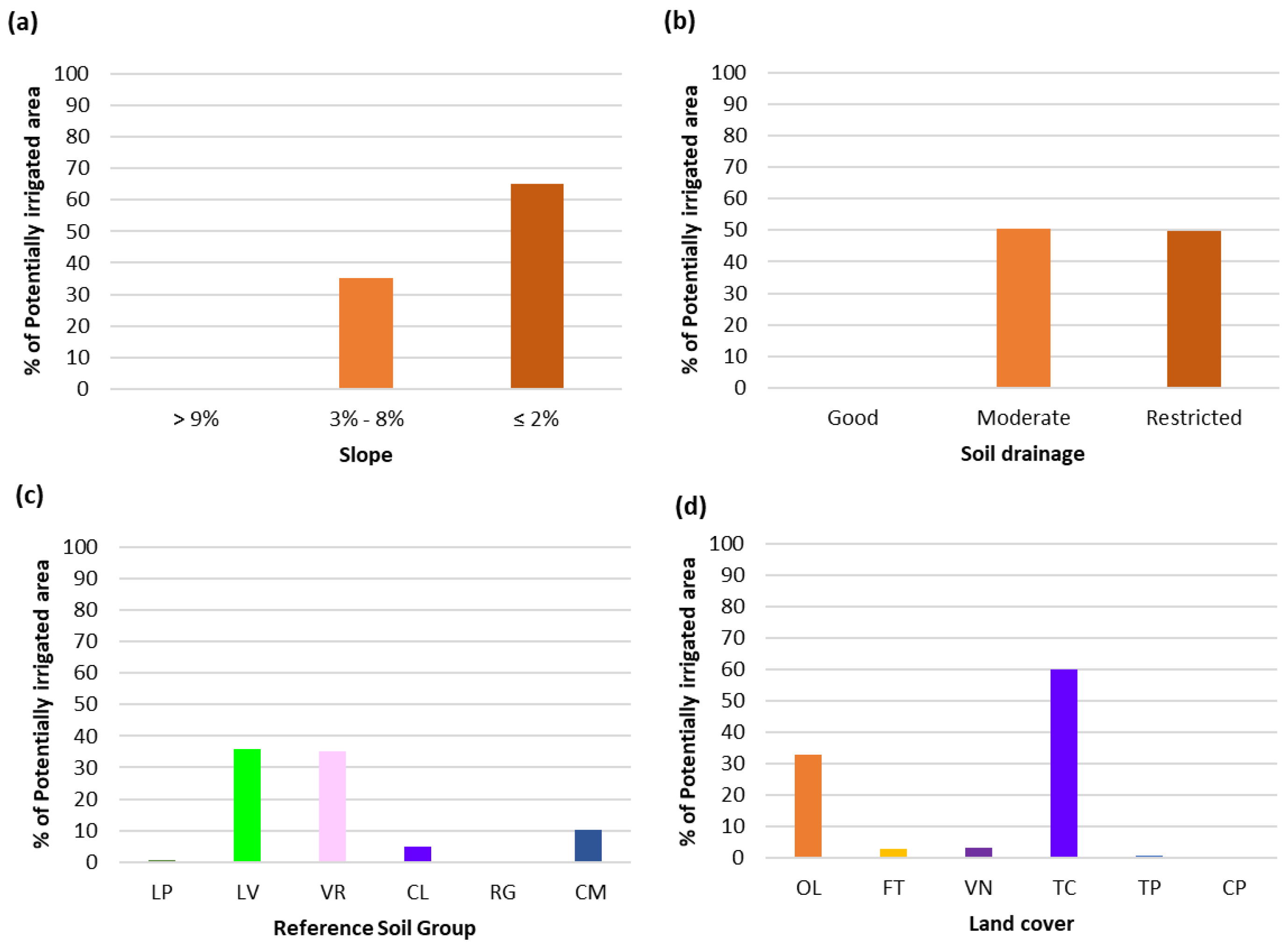

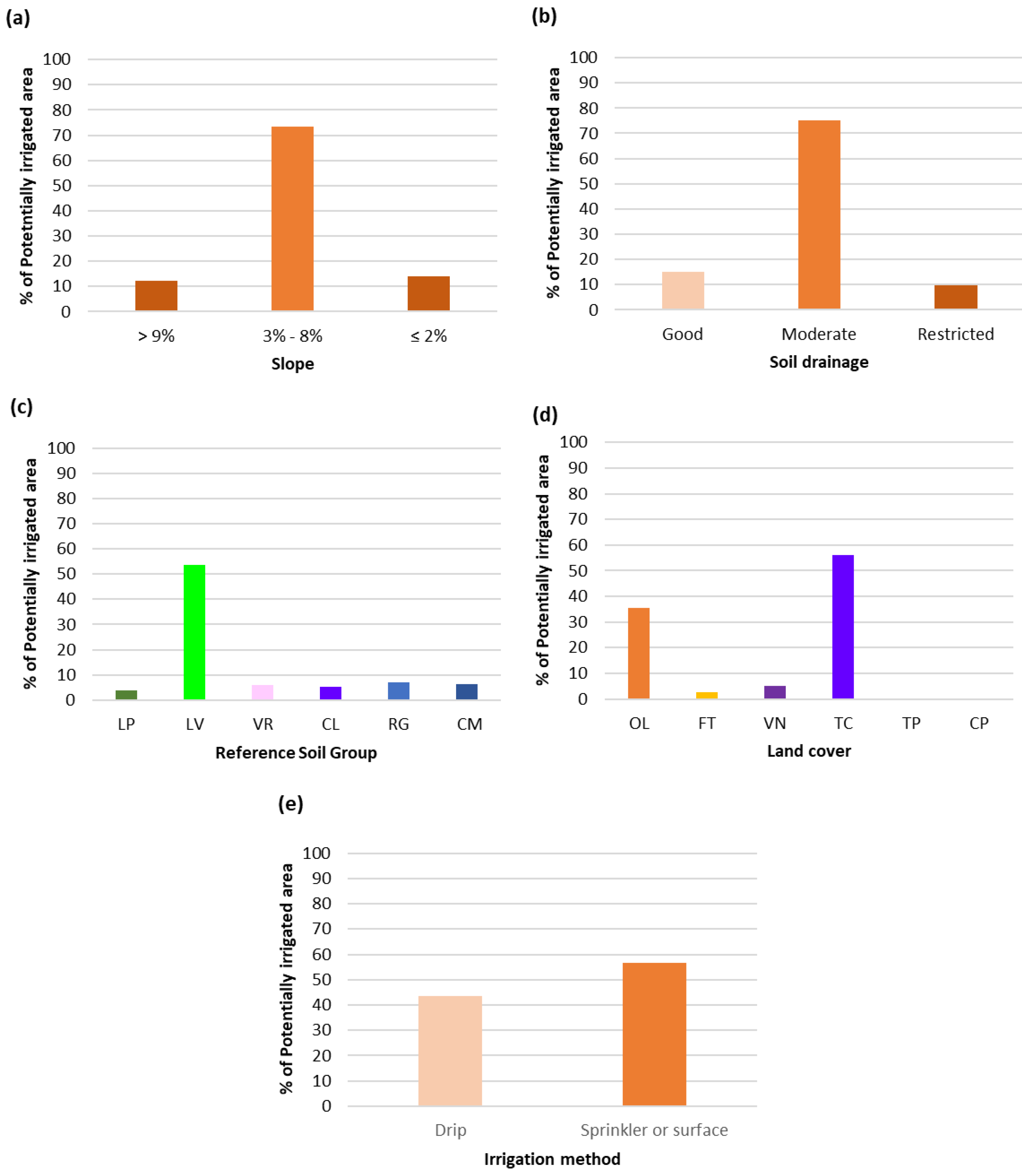

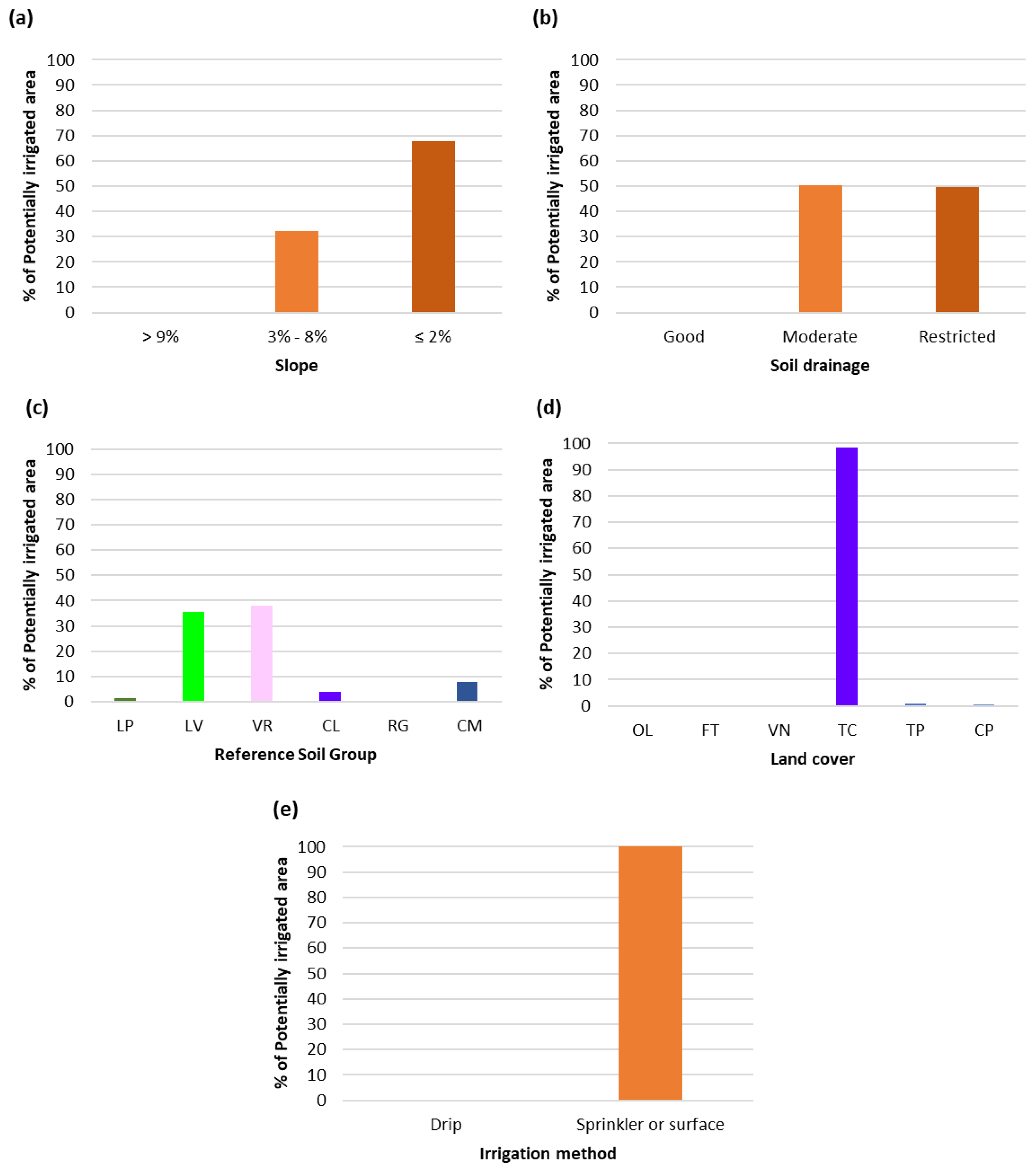

The application of the Salinization Risk (RSA) index to Inland Alentejo indicated that areas under moderate risk, where land-use practices should be monitored carefully, showed a prevalence of low slopes and fine-textured soils like Luvisols and Vertisols with limited drainage conditions.

The Sodification Risk (RSO) index calculations estimated a predominance of moderate- and high-risk potentially irrigated lands, corresponding to management practices which leave land exposed to agri-environmental degradation or are conductive to agri-environmental degradation. High-risk areas had a large incidence of low slope terrain, moderate-to-restricted soil drainage in high clay content Luvisols, Vertisols and Cambisols, and annual crops irrigated with surface or sprinkler systems.

Although the RSA and RSO indices have been proposed for a risk prediction purpose, and despite the fact that their validation with soil sampling or with in situ measurements with proximal sensors was outside the scope of this work, more precise knowledge is very important, especially in areas identified as of moderate and high risk. In this sense, it is our goal to develop work to validate the methodology presented in order to identify assumptions that must be adjusted or to integrate indicators of the current state of soil salinity and sodicity. Further possible developments of this methodology also include the application of these indices to different climate change scenarios, assessing the impact of expected increased aridity and decreased irrigation water quality on the risk of development of soil salinization and sodification processes in irrigated Mediterranean areas.

The proposed risk indices integrated climate, topography, soil, water quality, and crop indicators that are easily available for large scale assessments and territorial planning but can be applied at the farm level scale, encouraging farmers to get to know their land better, implement soil monitoring and adopt agronomic strategies that contribute to the sustainability of irrigated agriculture.