Climate-Driven Cryospheric Changes and Their Impacts on Glacier Runoff Dynamics in the Northern Tien Shan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

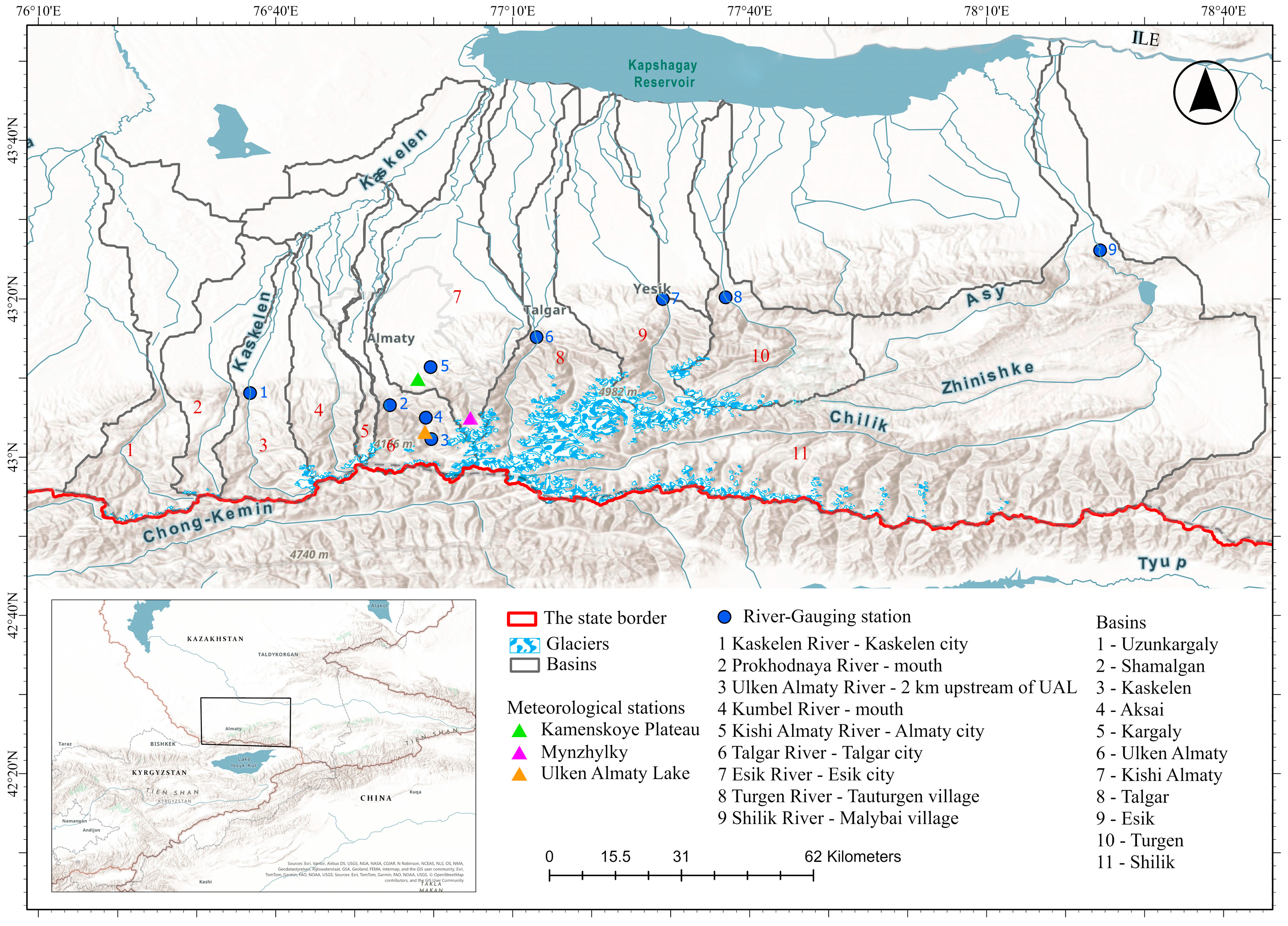

2.1. Study Area

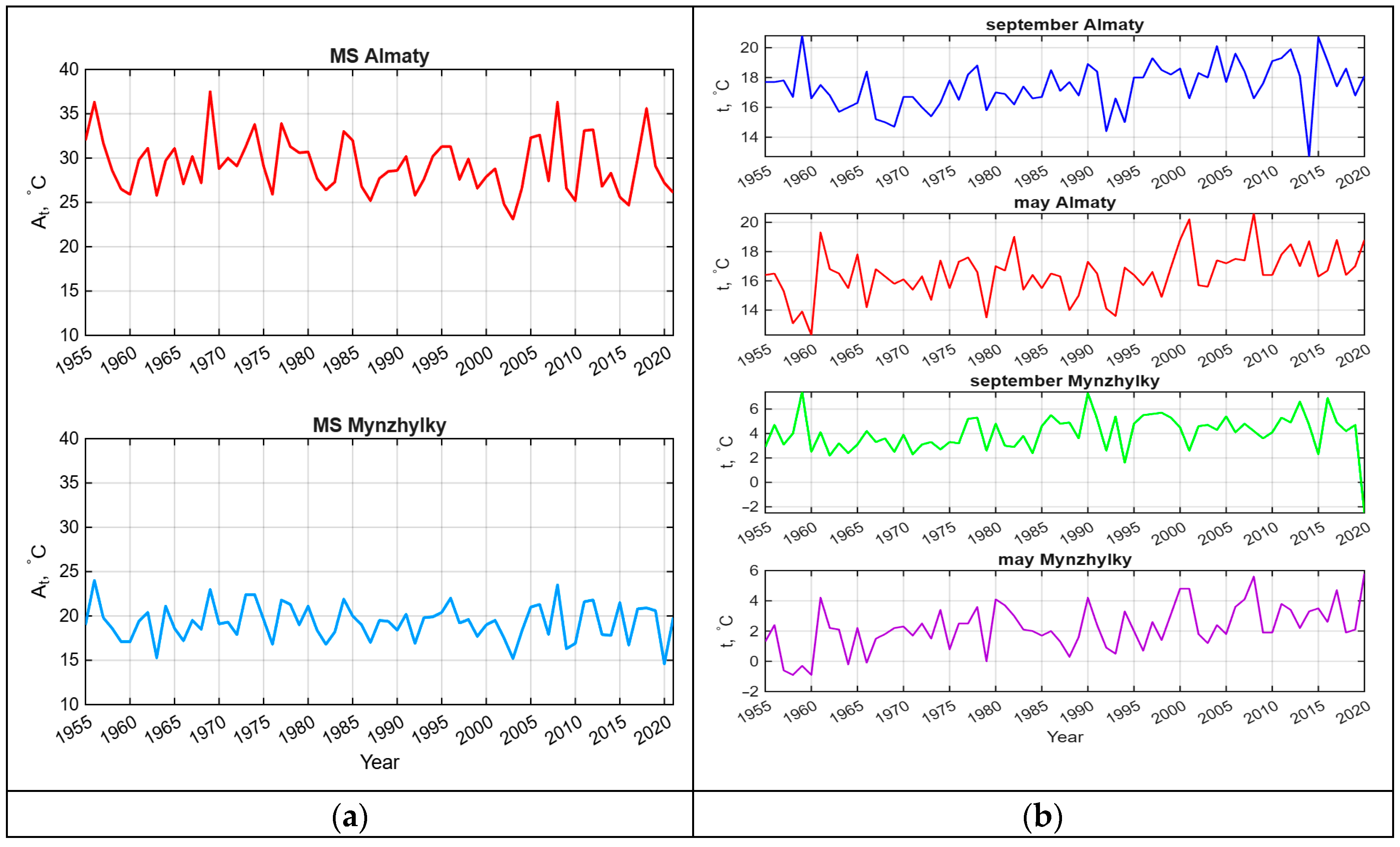

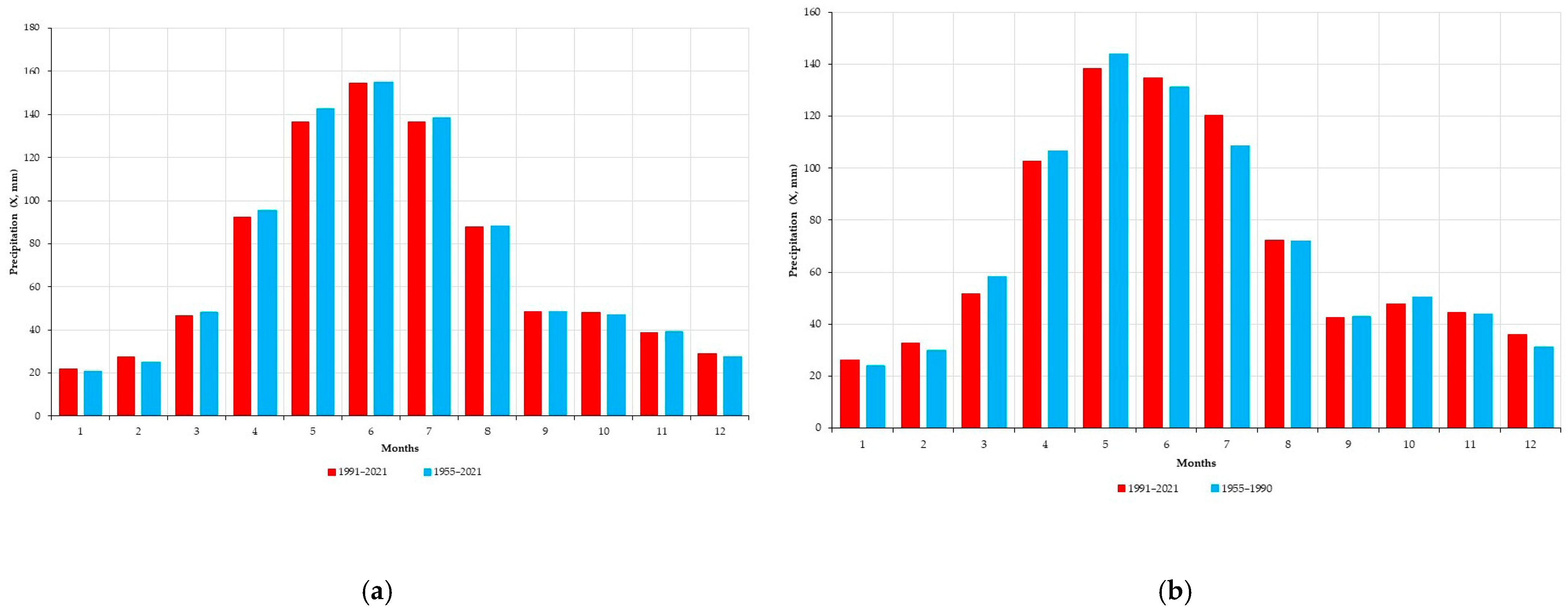

2.2. Temperature and Precipitation

2.3. Glacier Area Estimation

2.4. Runoff

2.5. Glacier Runoff

3. Results

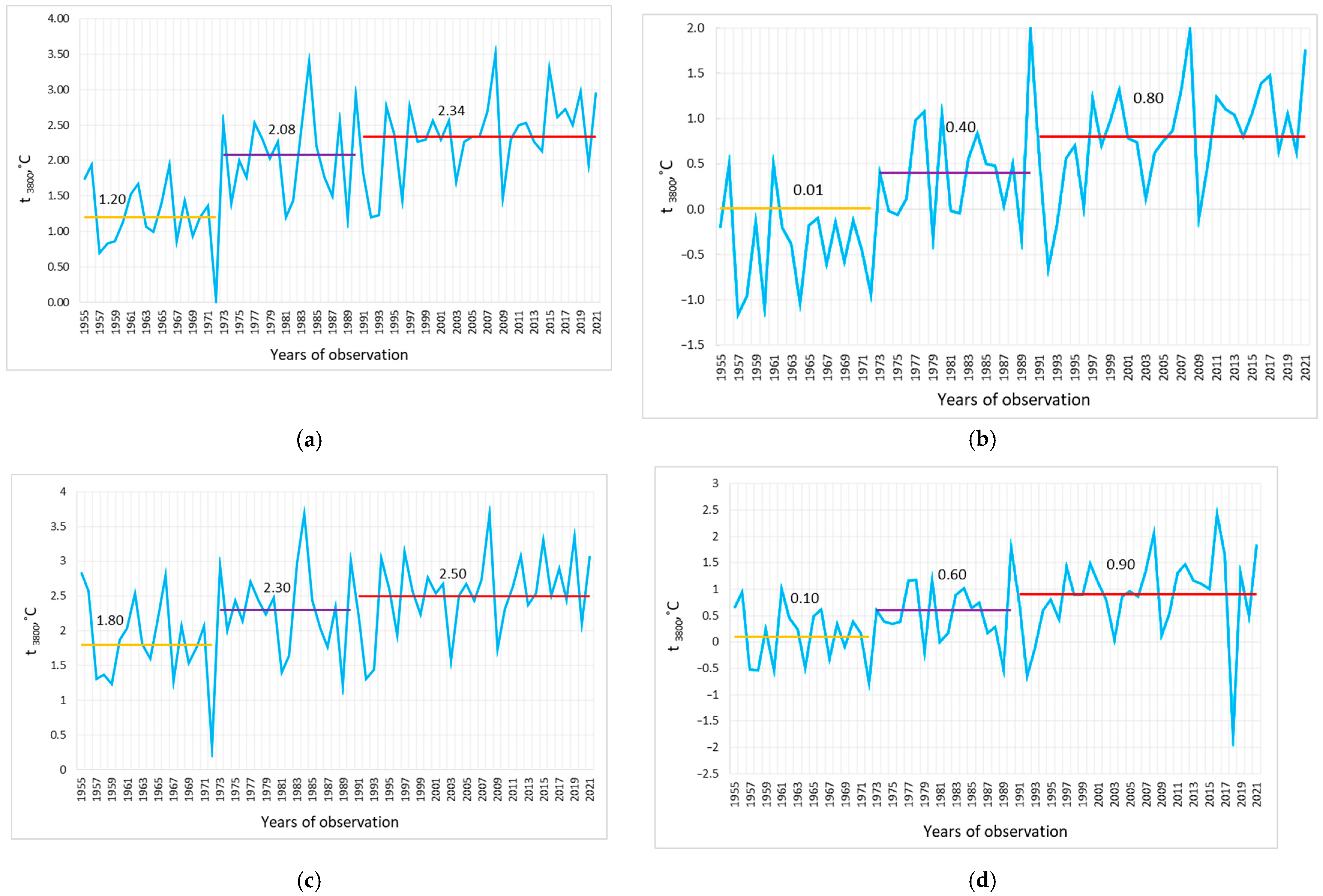

3.1. Changes in Firn Line Altitude and Meteorological Conditions

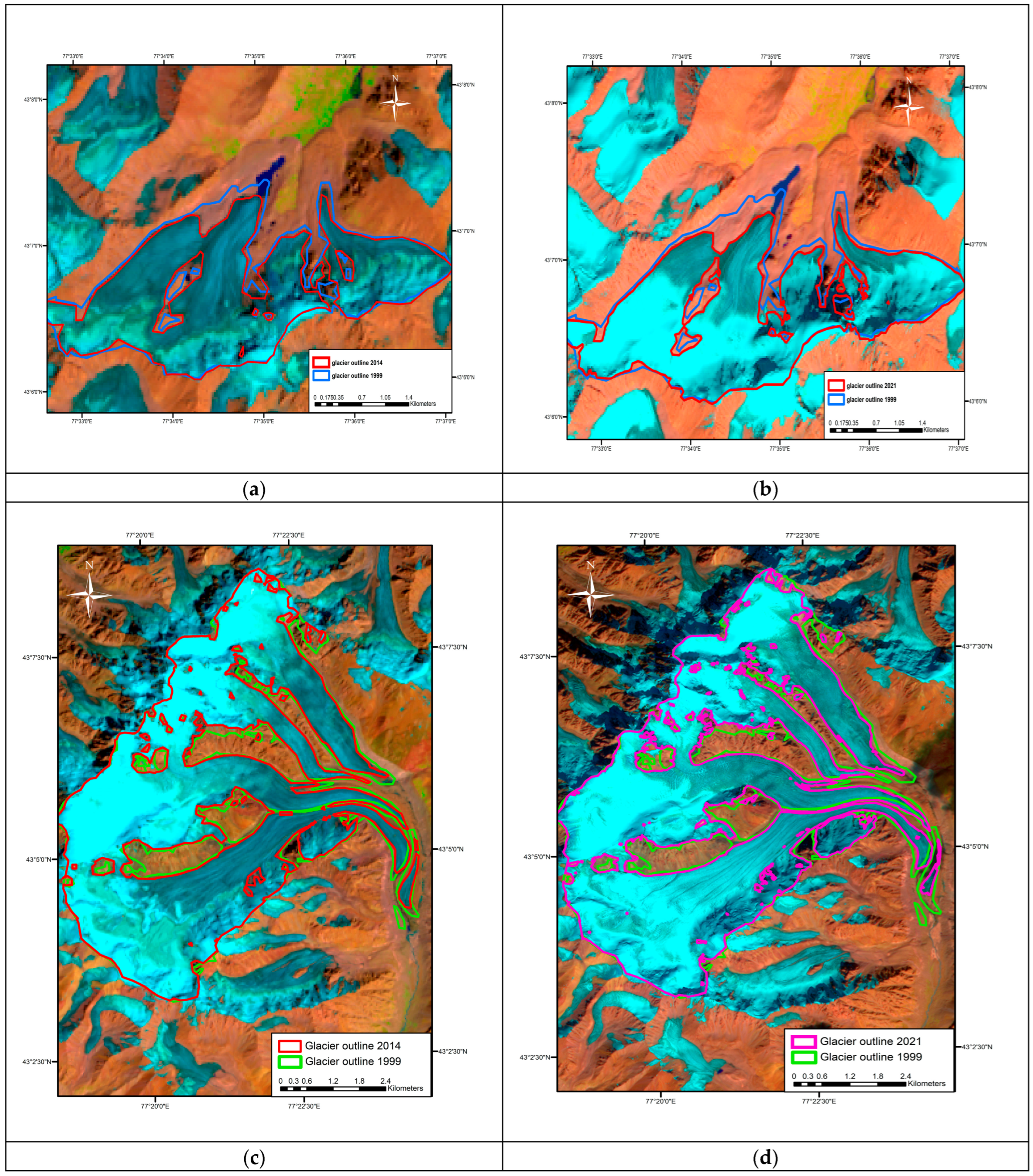

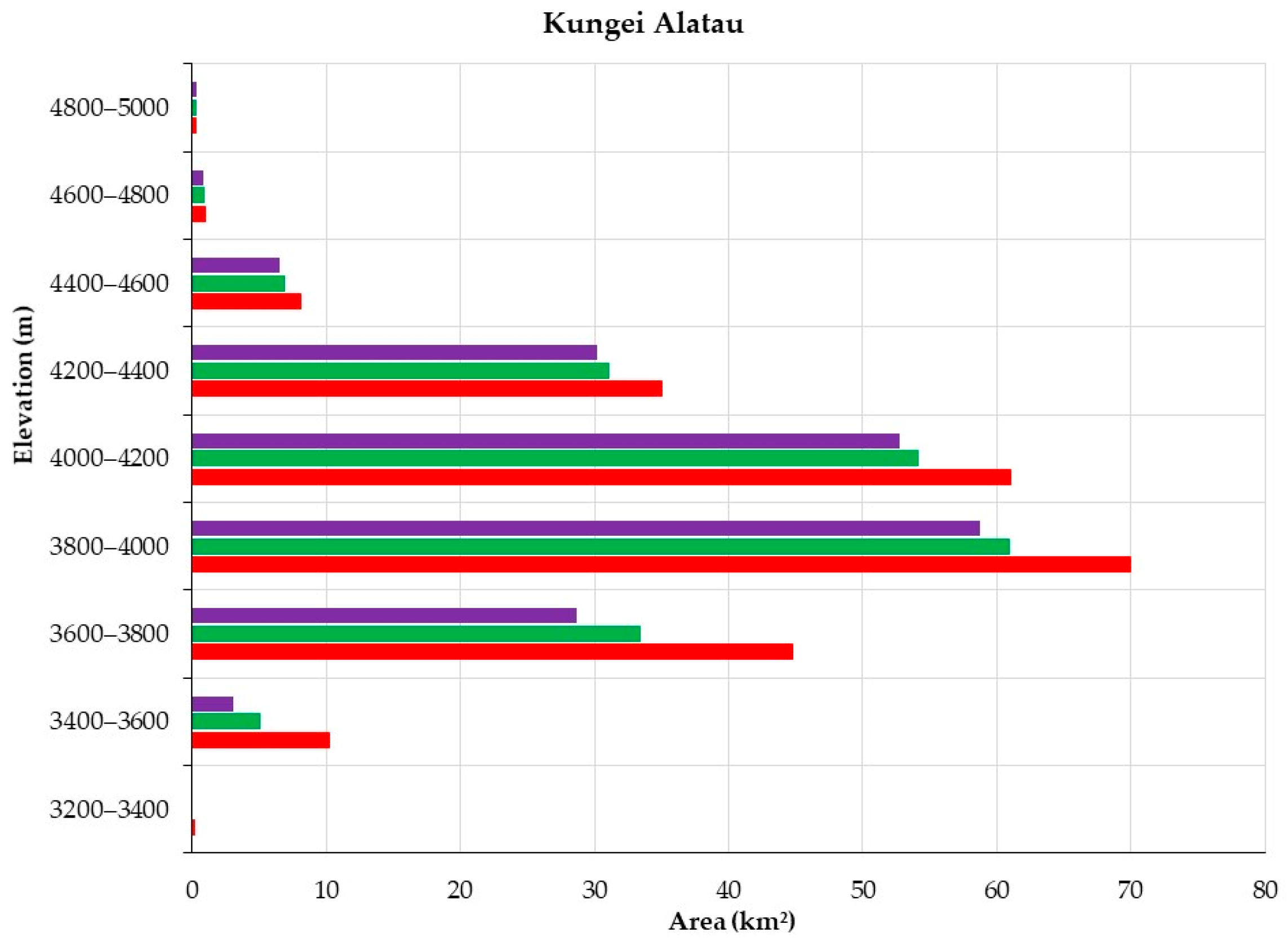

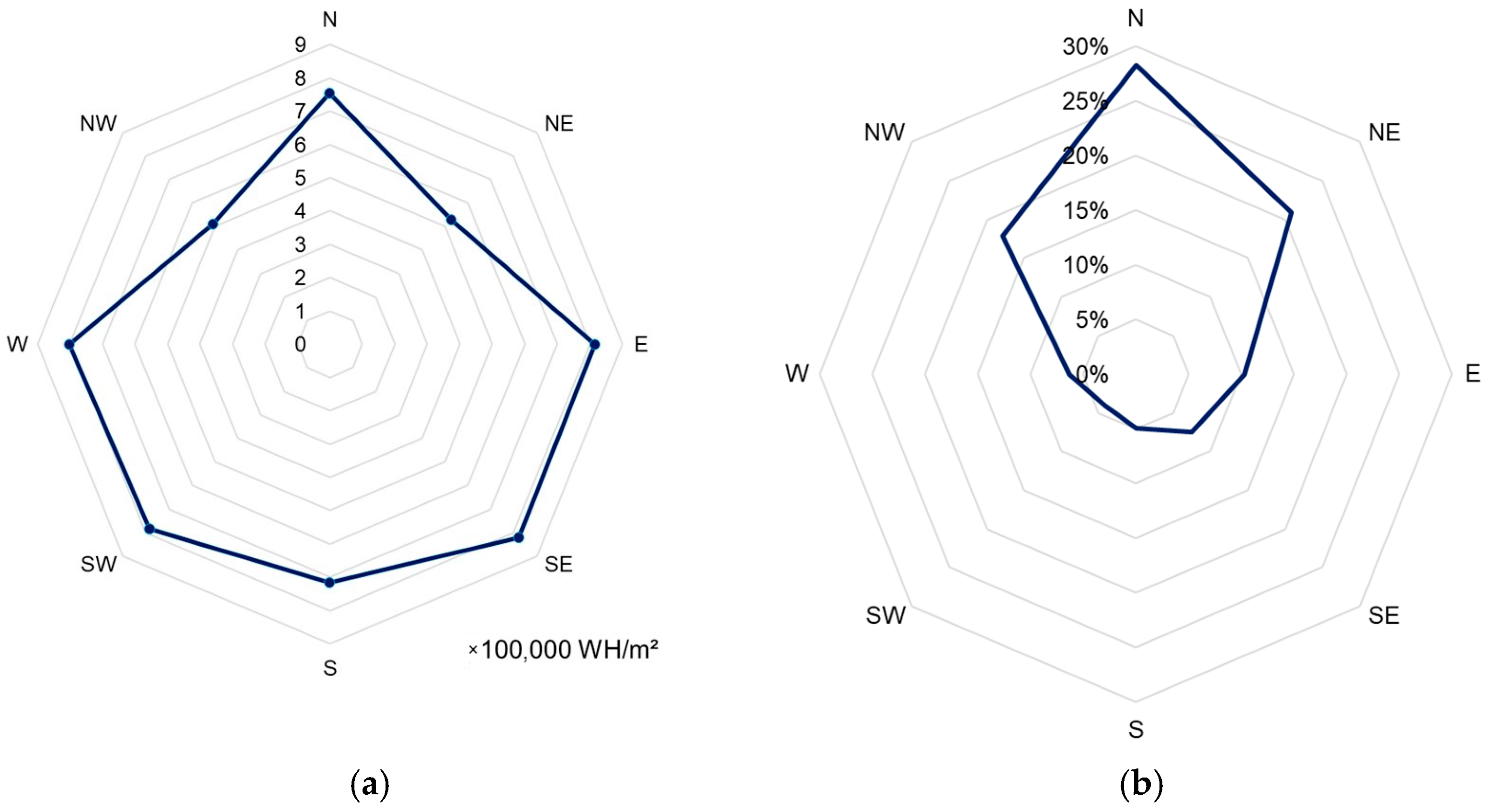

3.2. Glacier Area Change and Glacial Runoff Trend

4. Discussion

4.1. Firn Line Change and Climatic Controls

4.2. Glacier Area Change and Glacial Runoff Trends

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-009-15789-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sorg, A.; Bolch, T.; Stoffel, M.; Solomina, O.; Beniston, M. Climate Change Impacts on Glaciers and Runoff in Tien Shan (Central Asia). Nat. Clim Change 2012, 2, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A.F.; Immerzeel, W.W.; Kraaijenbrink, P.D.A.; Shrestha, A.B.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Climate Change Impacts on the Upper Indus Hydrology: Sources, Shifts and Extremes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, A.; Huss, M.; Rohrer, M.; Stoffel, M. The Days of Plenty Might Soon Be over in Glacierized Central Asian Catchments. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M.; Mercier, D.; Ruiz-Fernández, J.; McColl, S. Paraglacial Processes in Recently Deglaciated Environments. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, D.; Bishop, M.P.; Bush, A.B.G. Understanding Complex Debris-Covered Glaciers: Concepts, Issues, and Research Directions. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 652279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, M.; Hock, R. Global-Scale Hydrological Response to Future Glacier Mass Loss. Nat. Clim Change 2018, 8, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Marzeion, B.; Champollion, N.; Haeberli, W.; Langley, K.; Leclercq, P.; Paul, F. Observation-Based Estimates of Global Glacier Mass Change and Its Contribution to Sea-Level Change. Surv. Geophys. 2017, 38, 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohmura, A.; Boettcher, M. On the Shift of Glacier Equilibrium Line Altitude (ELA) under the Changing Climate. Water 2022, 14, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.; Rastner, P.; Azzoni, R.S.; Diolaiuti, G.; Fugazza, D.; Le Bris, R.; Nemec, J.; Rabatel, A.; Ramusovic, M.; Schwaizer, G.; et al. Glacier Shrinkage in the Alps Continues Unabated as Revealed by a New Glacier Inventory from Sentinel-2. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1805–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, M.; Frey, H.; Gärtner-Roer, I.; Nussbaumer, S.U.; Hoelzle, M.; Paul, F.; Haeberli, W.; Denzinger, F.; Ahlstrøm, A.P.; Anderson, B.; et al. Historically Unprecedented Global Glacier Decline in the Early 21st Century. J. Glaciol. 2015, 61, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolch, T.; Kulkarni, A.; Kääb, A.; Huggel, C.; Paul, F.; Cogley, J.G.; Frey, H.; Kargel, J.S.; Fujita, K.; Scheel, M.; et al. The State and Fate of Himalayan Glaciers. Science 2012, 336, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buytaert, W.; Moulds, S.; Acosta, L.; De Bièvre, B.; Olmos, C.; Villacis, M.; Tovar, C.; Verbist, K.M.J. Glacial Melt Content of Water Use in the Tropical Andes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 114014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, L.T.; Gallardo, L.; Andrade, M.; Baumgardner, D.; Borbor-Córdova, M.; Bórquez, R.; Casassa, G.; Cereceda-Balic, F.; Dawidowski, L.; Garreaud, R.; et al. Pollution and Its Impacts on the South American Cryosphere. Earth’s Future 2015, 3, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.F.; Burgess, E.; Arendt, A.A.; O’Neel, S.; Johnson, A.J.; Kienholz, C. Surface Melt Dominates Alaska Glacier Mass Balance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 5902–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scambos, T.; Moon, T. How Is Land Ice Changing in the Arctic, and What Is the Influence on Sea Level? Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2022, 54, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Recent Changes in Glaciers in the Northern Tien Shan, Central Asia. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, T.; Pohl, E.; Machguth, H.; Dehecq, A.; Barandun, M.; Kenzhebaev, R.; Kalashnikova, O.; Hoelzle, M. Glacier Runoff Variation Since 1981 in the Upper Naryn River Catchments, Central Tien Shan. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 780466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapiyev, V.; Wade, A.J.; Shahgedanova, M.; Saidaliyeva, Z.; Madibekov, A.; Severskiy, I. The Hydrochemistry and Water Quality of Glacierized Catchments in Central Asia: A Review of the Current Status and Anticipated Change. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 38, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foggin, J.M.; Lechner, A.M.; Emslie-Smith, M.; Hughes, A.C.; Sternberg, T.; Dossani, R. Belt and Road Initiative in Central Asia: Anticipating Socioecological Challenges from Large-Scale Infrastructure in a Global Biodiversity Hotspot. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeu, A.R.; Popov, N.V.; Blagovechshenskiy, V.P.; Askarova, M.A.; Medeu, A.A.; Ranova, S.U.; Kamalbekova, A.; Bolch, T. Moraine-Dammed Glacial Lakes and Threat of Glacial Debris Flows in South-East Kazakhstan. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 229, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Chen, Y.; Guan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Mao, W. Recent Climate and Hydrological Changes in a Mountain–Basin System in Xinjiang, China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 226, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.F. Need of Integrated Monitoring on Reference Glacier Catchments for Future Water Security in Himalaya. Water Secur. 2021, 14, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizen, V.B.; Aizen, E.M. Glacier Runoff Estimation and Simulation of Streamflow in the Peripheral Territory of Central Asia. Snow Glacier Hydrol. Proc. Int. Symp. Kathmandu 1993, 218, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, H.D. Asia’s Shrinking Glaciers Protect Large Populations from Drought Stress. Nature 2019, 569, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurakynov, S.; Kaldybayev, A.; Zulpykharov, K.; Sydyk, N.; Merekeyev, A.; Chepashev, D.; Nyssanbayeva, A.; Issanova, G.; Fang, G. Accelerated Glacier Area Loss in the Zhetysu (Dzhungar) Alatau Range (Tien Shan) for the Period of 1956–2016. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Long, A.; Yan, D.; Luo, G.; Wang, H. Predicting Ili River Streamflow Change and Identifying the Major Drivers with a Novel Hybrid Model. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgyzbay, K.; Kakimzhanov, Y.; Sagin, J. Climate Data Verification for Assessing Climate Change in Almaty Region of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Clim. Serv. 2023, 32, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetova, S.; Polyakova, S.; Duskayev, K.; Chigrinets, A. Water Resources and Regional Climate Change: Almaty Metropolis Case. Cent. Asian J. Sustain. Clim. Res. 2023, 2, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y. Monitoring of Glacier Area Changes in the Ili River Basin during 1992–2020 Based on Google Earth Engine. Land 2024, 13, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogutenko, L.; Severskiy, I.; Shahgedanova, M.; Lin, B. Change in the Extent of Glaciers and Glacier Runoff in the Chinese Sector of the Ile River Basin between 1962 and 2012. Water 2019, 11, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severskiy, I.; Vilesov, E.; Armstrong, R.; Kokarev, A.; Kogutenko, L.; Usmanova, Z.; Morozova, V.; Raup, B. Changes in Glaciation of the Balkhash-Alakol Basin, Central Asia, over Recent Decades. Ann. Glaciol. 2016, 57, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokarev, A.L.; Kapitsa, V.P.; Bolch, T.; Severskiy, I.V.; Kasatkin, N.E.; Shahgedanova, M.; Usmanova, Z.S. The Results of Geodetic Measurements of the Mass Balance of Some Glaciers in the Zailiyskiy Alatau (Trans-Ili Alatau). Led I Sneg 2022, 62, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitsa, V.; Shahgedanova, M.; Severskiy, I.; Kasatkin, N.; White, K.; Usmanova, Z. Assessment of Changes in Mass Balance of the Tuyuksu Group of Glaciers, Northern Tien Shan, Between 1958 and 2016 Using Ground-Based Observations and Pléiades Satellite Imagery. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.L.; Brooks, P.D.; Krogh, S.A.; Boisrame, G.F.S.; Carroll, R.W.H.; McNamara, J.P.; Harpold, A.A. Why Does Snowmelt-Driven Streamflow Response to Warming Vary? A Data-Driven Review and Predictive Framework. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 053004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, L.; Maussion, F.; Rounce, D.R.; Ultee, L.; Schmitt, P.; Lacroix, F.; Frölicher, T.L.; Schleussner, C.F. Irreversible Glacier Change and Trough Water for Centuries after Overshooting 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Bolch, T.; Goerlich, F.; Kutuzov, S.; Osmonov, A.; Pieczonka, T.; Shesterova, I. Surge-Type Glaciers in the Tien Shan (Central Asia). Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2017, 49, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgedanova, M.; Afzal, M.; Hagg, W.; Kapitsa, V.; Kasatkin, N.; Mayr, E.; Rybak, O.; Saidaliyeva, Z.; Severskiy, I.; Usmanova, Z.; et al. Emptying Water Towers? Impacts of Future Climate and Glacier Change on River Discharge in the Northern Tien Shan, Central Asia. Water 2020, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Bolch, T.; Mukherjee, K.; King, O.; Menounos, B.; Kapitsa, V.; Neckel, N.; Yang, W.; Yao, T. High Mountain Asian Glacier Response to Climate Revealed by Multi-Temporal Satellite Observations since the 1960s. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, L.P.; Uvarov, D.V. Study of glacial runoff in the Kishi Almaty River (Malaya Almatinka). Hydrometeorol. Ecol. 2013, 2, 112–130. [Google Scholar]

- Florath, J.; Keller, S.; Abarca-Del-rio, R.; Hinz, S.; Staub, G.; Weinmann, M. Glacier Monitoring Based on Multi-Spectral and Multi-Temporal Satellite Data: A Case Study for Classification with Respect to Different Snow and Ice Types. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, D.; Richter, N.; Grünberg, I. Remote Sensing-Derived Time Series of Transient Glacier Snowline Altitudes for High Mountain Asia, 1985–2021. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narama, C.; Duishonakunov, M.; Kääb, A.; Daiyrov, M.; Abdrakhmatov, K. The 24 July 2008 Outburst Flood at the Western Zyndan Glacier Lake and Recent Regional Changes in Glacier Lakes of the Teskey Ala-Too Range, Tien Shan, Kyrgyzstan. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severskiy, I.V. Water-Related Problems of Central Asia: Some Results of the (GIWA) International Water Assessment Program. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2004, 33, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolch, T. Climate Change and Glacier Retreat in Northern Tien Shan (Kazakhstan/Kyrgyzstan) Using Remote Sensing Data. Glob. Planet. Change 2007, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostay, Z.D.; Alimkulov, S.K.; Saparova, A.A. River Flow Resources of Kazakhstan. In Renewable Resources of Surface Water in the South and Southeast of Kazakhstan; Satbayev University: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2012; Volume 2, p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Du, W.; Ma, D.; Lyu, X.; Cheng, C. Comparison of Typical Alpine Lake Surface Elevation Variations and Different Driving Forces by Remote Sensing Altimetry Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.; Haritashya, U.K.; Kargel, J.S.; Karki, A. Transition of a Small Himalayan Glacier Lake Outburst Flood to a Giant Transborder Flood and Debris Flow. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y. Large Differences between Glaciers 3d Surface Extents and 2d Planar Areas in Central Tianshan. Water 2017, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatkova, M.E.; Seversky, I.V.; Usmanova, Z.S.; Kapitsa, V.P. Testing the Capabilities of the Operational Monitoring Methodology for Mountain-Glacier Systems. Geogr. Water Resour. 2024, 3, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilesov, E.N. Dynamics and Current State of Glaciation in the Mountains of Kazakhstan; Kazakh University: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2016; ISBN 601-04-1641-8. [Google Scholar]

- Palkov, N.N. The firn line as an indicator of the hydrological regime of glaciers. In Thermal and Water Regime of Glaciers in Kazakhstan; Nauka KazSSR: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1969; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, L.P. On the calculation of glacier ablation on the northern slope of the Zailiysky Alatau. In Use and Protection of Natural Resources in Kazakhstan; Al-Farabi KazGU: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1979; pp. 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Krenke, A.N.; Khodakov, V.G. On the relationship between surface glacier melt and air temperature. In Materials on the Glaciology of Tien Shan; Siberian Altai: Moscow, Russia, 1966; Volume 12, pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Vilesov, E.N.; Cherkasov, P.A. Catalogue of Glaciers of the USSR. Central and Southern Kazakhstan, Lake Balkhash Basin, Part 2; Hydrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1980; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Data on the Regime and Resources of Surface Waters of the Land. Available online: https://www.Kazhydromet.Kz (accessed on 25 December 2025).

- Cherkasov, P.A. Glacier ablation taking into account exposure and altitude (based on the example of the Dzungarian Alatau). In Collection of Glaciology and Climatology of Mountainous Countries; Search Russian Databases: Moscow, Russia, 1973; Volume 24, p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Severskiy, I.; Mukanova, B.; Kapitsa, V.; Tatkova, M.; Kokarev, A.; Shesterova, I. Changes in the Glaciation of the Northern Slope of Ile Alatau over the Seventy-Year Period. J. Geogr. Environ. Manag. 2024, 73, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Climate and Glaciers; IAHS: Bengaluru, India, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, R.J. Temperature and Precipitation Climate at the Equilibrium-Line Altitude of Glaciers Expressed by the Degree-Day Factor for Melting Snow. J. Glaciol. 2008, 54, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mernild, S.H.; Pelto, M.; Malmros, J.K.; Yde, J.C.; Knudsen, N.T.; Hanna, E. Identification of Snow Ablation Rate, ELA, AAR and Net Mass Balance Using Transient Snowline Variations on Two Arctic Glaciers. J. Glaciol. 2013, 59, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääb, A.; Bolch, T.; Casey, K.; Heid, T.; Kargel, J.S.; Leonard, G.J.; Paul, F.; Raup, B.H. Glacier Mapping and Monitoring Using Multispectral Data. In Global Land Ice Measurements from Space; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, B.; Hölbling, D.; Nuth, C.; Strozzi, T.; Dahl, S. Decadal Scale Changes in Glacier Area in the Hohe Tauern National Park (Austria) Determined by Object-Based Image Analysis. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Gupta, R.P.; Arora, M.K. Delineation of Debris-Covered Glacier Boundaries Using Optical and Thermal Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. Lett. 2010, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, F.; Barrand, N.E.; Baumann, S.; Berthier, E.; Bolch, T.; Casey, K.; Frey, H.; Joshi, S.P.; Konovalov, V.; Le Bris, R.; et al. On the Accuracy of Glacier Outlines Derived from Remote-Sensing Data. Ann. Glaciol. 2013, 54, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center. USGS EROS Archive—Digital Elevation—Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 1 Arc-Second Global; Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center: Near Sioux Falls, SD, USA, 2018.

- Abdrakhimov, R.G.; Akzharkynova, A.N.; Dautaliyeva, M.E.; Rodrigo-Ilarri, J.; Rodrigo-Clavero, M.-E.; Nahiduzzaman, K.M. Assessment of Changes in Hydrometeorological Indicators and Intra-Annual River Runoff in the Ile River Basin. Water 2024, 16, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazhydromet River Basins of Lake Balkhash and Drainless Areas of Central Kazakhstan. In Long-Term Data on the Regime and Resources of Surface Waters of the Land; Climate Change Impact: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 2006; Volume 4, pp. 17–285.

- State Water Cadastre of the Republic of Kazakhstan Lake Balkhash Basin and Drainless Areas of Central Kazakhstan. Long-Term Data Regime Resour. Surf. Waters Land 2002, 2, 284.

- State Water Cadastre of the Republic of Kazakhstan Long-Term Data on the Regime and Resources of Surface Waters of the Land, 1990–1991. Lake Balkhash Basin Drainless Areas Cent. Kazakhstan 2004, 1, 171.

- Rozhdestvenskii, A.; Chebotarev, A. Statisticheskie Metody v Gidrologii [Statistical Methods in Hydrology]; Leningrad, Publ. Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1974; 424p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rozhdestvenskaya, A.V.; Lobanov, A.G.; Plitkin, G.A.; Vladimirov, A.M.; Tumanovskaya, S.M. Gidrometeoizdat Guidelines for Determining Design Hydrological Characteristics; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirov, A.M. Hydrological Calculations; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Abdrakhimov, R.G.; Amirgalieva, A.S.; Dauletiarov, K.B.; Zyarov, A.M. Modern Trends in the Annual Runoff of the Ile River and Its Major Tributaries under Climate Warming; Series 5. Geography (No. 4); Bulletin of Moscow University: Moscow, Russia, 2021; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vilesov, E.N. Changes in the main climate parameters of the city of Almaty and their trends over 100 years (1915–2015). Issues Geogr. Geoecology 2015, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vilesov, E.N.; Khonin, R.V. Catalogue of Glaciers of the USSR. Central and Southern Kazakhstan, Lake Balkhash Basin. Basins of the Left Tributaries of the Ili River from the Mouth of the Kurty River to the Mouth of the Turgen River, Part 1; Hydrometeoizdat: Leningrad, Russia, 1967; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Shultz, V.L. Rivers of Central Asia. In Rivers of Central Asia. Part I; Hydrometeorological Publishing House: Leningrad, Russia, 1965; pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chigrinets, A.G.; Duskayev, K.K.; Mazur, L.P.; Chigrinets, L.Y.; Akhmetova, S.T.; Mussina, A.K. Evaluation and Dynamics of the Glacial Runoff of the Rivers of the Ile Alatau Northern Slope in the Context of Global Warming. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J. Changes in the End-of-Summer Snow Line Altitude of Summer-Accumulation-Type Glaciers in the Eastern Tien Shan Mountains from 1994 to 2016. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, N.; Kehrwald, N.M.; Mao, R.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, X. Temporal and Spatial Changes in Western Himalayan Firn Line Altitudes from 1998 to 2009. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 118, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, N.; Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Q. Variations in Firn Line Altitude and Firn Zone Area on Qiyi Glacier, Qilian Mountains, Over the Period of 1990 to 2011. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2015, 47, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, M.; van Pelt, W.; Machguth, H.; Fiddes, J.; Hoelzle, M.; Pertziger, F. Long-Term Firn and Mass Balance Modelling for Abramov Glacier in the Data-Scarce Pamir Alay. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 5001–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žebre, M.; Colucci, R.R.; Giorgi, F.; Glasser, N.F.; Racoviteanu, A.E.; Del Gobbo, C. 200 Years of Equilibrium-Line Altitude Variability across the European Alps (1901–2100). Clim. Dyn. 2021, 56, 1183–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabatel, A.; Letréguilly, A.; Dedieu, J.-P.; Eckert, N. Changes in Glacier Equilibrium-Line Altitude in the Western Alps from 1984 to 2010: Evaluation by Remote Sensing and Modeling of the Morpho-Topographic and Climate Controls. Cryosphere 2013, 7, 1455–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabatel, A.; Francou, B.; Soruco, A.; Gomez, J.; Cáceres, B.; Ceballos, J.L.; Basantes, R.; Vuille, M.; Sicart, J.-E.; Huggel, C.; et al. Current State of Glaciers in the Tropical Andes: A Multi-Century Perspective on Glacier Evolution and Climate Change. Cryosphere 2013, 7, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, L.J.; Lea, J.M.; Erb, M.P.; McKay, N.P.; Phillips, M.; Lamantia, K.A.; Kaufman, D.S. Arctic Glacier Snowline Altitudes Rise 150 m over the Last 4 Decades. Cryosphere 2024, 18, 3591–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokarev, A.; Shesterova, I. Izmenenie Lednikovih System Severnogo Sklona Zailiiskogo Alatau vo Vtoroi Polovine XX i Nachale XXI Vekov [Change of the Glacier Systems on the Northern Slope of Zailiyskiy Alatau for the Second Half of XX and the Beginning of XXI Centuries]. Led I Sneg Ice Snow 2011, 4, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Usmanova, Z.; Shahgedanova, M.; Severskiy, I.; Nosenko, G.; Kapitsa, V. Assessment of Glacier Area Change in the Tekes River Basin, Central Tien Shan, Kazakhstan Between 1976 and 2013 Using Landsat and KH-9 Imagery 2016. Cryosphere Discuss. 2016, 2016, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Narama, C.; Shimamura, Y.; Nakayama, D.; Abdrakhmatov, K. Recent Changes of Glacier Coverage in the Western Terskey-Alatoo Range, Kyrgyz Republic, Using Corona and Landsat. Proc. Ann. Glaciol. 2006, 43, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jia, L.; Menenti, M.; Zhou, J.; Ren, S. Glacier Area and Snow Cover Changes in the Range System Surrounding Tarim from 2000 to 2020 Using Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, N.; Chen, A.; Liang, Q.; Yang, D. Slight Change of Glaciers in the Pamir over the Period 2000–2017. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2022, 54, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinthaler, J.; Paul, F. Reconstructed Glacier Area and Volume Changes in the European Alps since the Little Ice Age. Cryosphere 2025, 19, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Deng, H.; Fang, G.; Li, Z. Changes in Central Asia’s Water Tower: Past, Present and Future. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Liu, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bolch, T.; Kääb, A.; Duan, S.; Miao, W.; Kang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Interdecadal Glacier Inventories in the Karakoram since the 1990s. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraer, M.; Mark, B.G.; McKenzie, J.M.; Condom, T.; Bury, J.; Huh, K.-I.; Portocarrero, C.; Gómez, J.; Rathay, S. Glacier Recession and Water Resources in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca. J. Glaciol. 2012, 58, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouberton, A.; Shaw, T.E.; Miles, E.; Kneib, M.; Fugger, S.; Buri, P.; McCarthy, M.; Kayumov, A.; Navruzshoev, H.; Halimov, A.; et al. Snowfall Decrease in Recent Years Undermines Glacier Health and Meltwater Resources in the Northwestern Pamirs. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhenqi, S.; Shijin, W.; Zhongqin, L. Characteristics of Runoff Changes and Their Climatic Factors in Two Different Glacier-Fed Basins. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2024, 56, 2356671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.A.; Gleason, C.J.; Brown, C.; Vergopolan, N.; Lummus, M.M.; Stearns, L.A.; Li, D.; Andrews, L.C.; Basnyat, D.; Brinkerhoff, C.B.; et al. Accelerating River Discharge in High Mountain Asia. AGU Adv. 2025, 6, C21A-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahgedanova, M.; Afzal, M.; Severskiy, I.; Usmanova, Z.; Saidaliyeva, Z.; Kapitsa, V.; Kasatkin, N.; Dolgikh, S. Changes in the Mountain River Discharge in the Northern Tien Shan since the Mid-20th Century: Results from the Analysis of a Homogeneous Daily Streamflow Data Set from Seven Catchments. J. Hydrol. 2018, 564, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, L.E.L.; Pietroniro, A.; Demuth, M.N. Glacier Contribution to the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers. Hydrol. Process. 2009, 23, 2640–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.N. Climatic Warming, Glacier Recession and Runoff from Alpine Basins after the Little Ice Age Maximum. Ann. Glaciol. 2008, 48, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, A.; Hock, R.; Radić, V. Global Response of Glacier Runoff to Twenty-first Century Climate Change. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2014, 119, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, V.; Hock, R. Glaciers in the Earth’s Hydrological Cycle: Assessments of Glacier Mass and Runoff Changes on Global and Regional Scales. Surv. Geophys. 2014, 35, 813–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WRS2 Path-Row | Date | Satellite and Sensor | Resolution (m) | The Suitability of the Scenes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 149–030 | 08 August 1999 | Landsat ETM+ | 15/30/60 | Main |

| 150–030 | 16 September 1999 | Landsat ETM+ | 15/30/60 | Additional information |

| 149–030 | 09 August 2014 | Landsat OLI | 15/30/60 | Main |

| 27 September 2021 | Sentinel-2 | 15/30/60 | Main | |

| 07 September 2021 | Sentinel-2 | 10/20/60 | Main |

| River-Post | Elevation, m a.s.l | Catchment Area, km2 | Where Does It Flow into | The Year of the Opening of the Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaskelen River-Kaskelen city | 1129.67 | 290 | Kapchagai reservoir | 1928 |

| Prokhodnaya River-mouth | 1422.17 | 82 | Ulken Almaty River | 1951 |

| Ulken Almaty River-2 km upstream of Ulken Almaty Lake | 2654.19 | 71.8 | Kaskelen River | 1928 |

| Kumbel river-mouth | 2150.44 | 22.4 | Ulken Almaty River | 1952 |

| Small (Kishi) Almaty River-Almaty city (mouth of Butakovka River, dam) | 1175.14 | 118 | Kaskelen River | 1916 |

| Talgar River-Talgar city | 1190.37 | 444 | Kapchagai reservoir | 1928 |

| Esik river | Kapchagai reservoir | |||

| Turgen River-Tauturgen village | 1141.79 | 614 | Kapchagai reservoir | 1932 |

| Shelek River-Malybai village | 862.96 | 4300 | Kapchagai reservoir | 1928 |

| Meteorological Station | Period | H, m | tVI–VIII, °C | XVI–VIII, mm | ∆H, m | ∆tVI–VIII, °C | ∆XVI–VIII, mm | H, % | tVI–VIII, % | XVI–VIII, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mynzhylky | 1955–1972 | 3719 | 6.54 | 899 | 62 | 0.87 | −41 | 2.22 | 11.7 | −4.8 |

| 1973–1990 | 3781 | 7.41 | 858 | 20 | 0.27 | 10 | 0.34 | 3.52 | 1.15 | |

| 1991–2021 | 3801 | 7.68 | 868 | |||||||

| Ulken Almaty Lake | 1955–1972 | 3750 | 10.4 | 870 | 35 | 0.5 | −58 | 1.61 | 4.59 | 0.06 |

| 1973–1990 | 3785 | 10.9 | 812 | 15 | 0.2 | 35 | 0.03 | 1.80 | 0.02 | |

| 1991–2021 | 3800 | 11.1 | 847 |

| Meteorological Station | Absolute Elevation, m | Height Difference, m | Period | tH, °C | ∆t, °C | tH, °C | ∆t, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tVI–VIII, °C | VI–VIII | tV–IX, °C | V2013IX | ||||

| Mynzhylky | 3017 | 800 | 1955–1972 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| 1973–1990 | 2.08 | 0.40 | |||||

| 1991–2021 | 2.34 | 0.26 | 0.80 | 0.40 | |||

| Ulken Almaty Lake | 2516 | 1284 | 1955–1972 | 1.80 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 |

| 1973–1990 | 2.30 | 0.60 | |||||

| 1991–2021 | 2.50 | 0.20 | 0.90 | 0.30 | |||

| Tuyuksu I | 3420 | 380 | 1955–1972 | 3.78 | 0.88 | 2.20 | 0.80 |

| 1973–1990 | 4.66 | 3.00 | |||||

| 1991–2021 | 4.92 | 0.26 | 3.40 | 0.40 |

| Meteorological Station | X, mm | H, m | , mm | X (3800), mm | ɛ, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mynzhylky | 870 | 3017 | 16.6 | 862.63 | 20.2 | 2.34 |

| Ulken Almaty Lake | 839 | 2516 | 18.9 | 792.00 | 34.1 | 4.31 |

| Kamenskoye Plateau | 886 | 1317 | 18.6 | 862.64 | 36.6 | 4.75 |

| Meteorological Station | Absolute Elevation, m | Height Difference, m | Period | X3800, mm | ∆X3800, mm | X3800, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3017 | 1955–1972 | 971 | ||||

| Mynzhylky | 800 | 1973–1990 | 928 | −43 | −4.6 | |

| 1991–2021 | 937 | 9 | 1.0 | |||

| 2516 | 1955–1972 | 943 | −61 | −6.9 | ||

| Ulken Almaty Lake | 1284 | 1973–1990 | 882 | |||

| 1991–2021 | 916 | 34 | 3.7 | |||

| 3420 | 1955–1972 | 934 | ||||

| Tuyuksu I | 380 | 1973–1990 | 892 | −42 | −4.7 | |

| 1991–2021 | 905 | 13 | 1.4 |

| Left-Bank Tributaries of the Ile River Basin | F, km2 | F, % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 1999 | 2014 | 2021 | 1955–1999 | 1955–2021 | 1999–2014 | 1999–2021 | 2014–2021 | |

| Uzunkargaly river | 10.6 | 9.5 ± 0.4 | 6.41 ± 0.26 | 5.38 ± 0.22 | −10.3% | −49.3% | −32.5% | −43.4% | −16.1% |

| Shamalgan river | 1.6 | 1.2 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | −24.6% | −81.9% | −68.4% | −75.9% | −23.8% |

| Kaskelen river | 9.6 | 8.8 ± 0.37 | 5.95 ± 0.25 | 5.02 ± 0.21 | −8.2% | −47.7% | −32.5% | −43.1% | −15.7% |

| Aksai river | 12.7 | 10.2 ± 0.43 | 7.06 ± 0.3 | 6.39 ± 0.26 | −19.5% | −49.6% | −30.9% | −37.4% | −9.4% |

| Kargalinka river | 3.9 | 2.5 ± 0.11 | 1.57 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.06 | −35.0% | −61.0% | −38.2% | −40.0% | −3.0% |

| Prokhadnaya river | 6.0 | 3.80 ± 0.16 | 1.92 ± 0.08 | 1.72 ± 0.07 | −36.7% | −71.3% | −49.5% | −54.7% | −10.4% |

| Ulken Almaty river | 24.9 | 17.2 ± 0.72 | 12.3 ± 0.52 | 10.74 ± 0.45 | −31.7% | −57.3% | −28.7% | −37.5% | −12.3% |

| Kishi Almaty river | 9.1 | 6.8 ± 0.28 | 4.64 ± 0.19 | 3.78 ± 0.16 | −25.5% | −58.4% | −31.5% | −44.1% | −18.3% |

| Talgar river | 107.9 | 82.5 ± 3.47 | 64.96 ± 2.73 | 60.41 ± 2.54 | −23.5% | −44.0% | −21.3% | −26.8% | −7.0% |

| Esik river | 48.5 | 35.4 ± 1.49 | 28.22 ± 1.19 | 27.48 ± 1.15 | −27.1% | −43.3% | −20.2% | −22.3% | −2.6% |

| Turgen river | 34.8 | 24.7 ± 1.04 | 19.49 ± 0.82 | 18.9 ± 0.79 | −28.9% | −45.7% | −21.2% | −23.6% | −3.0% |

| Shilik river | 276.9 | 230.0 ± 9.66 | 192.1 ± 8.07 | 180.5 ± 7.58 | −16.9% | −34.8% | −16.5% | −21.5% | −6.0% |

| without numbering | 2.60 | 1.52 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | −41.5% | −72.5% | −46.2% | −53.0% | −12.6% |

| River Basin | Fgl, km2 2021 | Fice/Fcatchment area, % | Water Discharge | Flow Volume | Glacial Runoff Volume (Average) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q, m3/s | Qveg, m3/s | WI–XII, million m3 | Wgl, Million m3 | in % from W | |||

| Kaskelen River—Kaskelen City | 5.02 | 1.7 | 4.25 | 7.00 | 134 | 14 | 11 |

| Prokhodnaya River | 1.72 | 2.1 | 1.58 | 2.50 | 50 | 7 | 13 |

| Ulken Almaty River | 10.8 | 15.0 | 2.82 | 4.60 | 89 | 30 | 34 |

| Kishi Almaty River—Almaty City | 3.80 | 3.2 | 1.97 | 3.10 | 62 | 11 | 17 |

| Talgar River—Talgar City | 60.4 | 13.6 | 10.3 | 17.3 | 325 | 132 | 41 |

| Esik River—Esik City | 27.5 | 10.7 | 4.80 | 7.80 | 151 | 58 | 38 |

| Turgen River—Turgen Village | 18.9 | 3.1 | 7.13 | 12.1 | 225 | 41 | 18 |

| Shilik River—Malybai Village | 180.5 | 4.2 | 39.6 | 72.2 | 1250 | 363 | 29 |

| River Basin | Periods | Annual Runoff Volume | Glacial Runoff Volume | Volume of Glacial Runoff from Annual Runoff | Volume of Vegetation Runoff | Glacial Runoff Volume from Vegetation Runoff | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WI–XII, Million m3 | ∆W, % | Wgl, Million m3 | ∆Wgl, % | Wgl from WI–XII, % | ∆, % | Wveg, mln m3 | ∆Wveg, % | Wgl from Wveg, % | ∆, % | ||

| Kaskelen River—Kaskelen City | 1955–1990 | 140.3 | −9 | 14.5 | −4 | 10.3 | 6 | 96.0 | −8 | 10.8 | 15 |

| 1991–2021 | 127.1 | 13.9 | 10.9 | 88.0 | 12.4 | ||||||

| Prokhodnaya River | 1955–1990 | 49.3 | 2 | 7.9 | −37 | 16.0 | −38 | 34.0 | −3 | 47.1 | −36 |

| 1991–2021 | 50.1 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 33.0 | 30.2 | ||||||

| Ulken Almaty River | 1955–1990 | 72.8 | 48 | 34.0 | −24 | 46.7 | −49 | 49.8 | 50 | 93.8 | −66 |

| 1991–2021 | 108.1 | 26.0 | 24.1 | 74.8 | 32.2 | ||||||

| Kishi Almaty River—Almaty City | 1955–1990 | 63.5 | −5 | 11.5 | −16 | 18.1 | −11 | 41.1 | −2 | 44.1 | −9 |

| 1991–2021 | 60.5 | 9.7 | 16.0 | 40.1 | 40.0 | ||||||

| Talgar River—Talgar City | 1955–1990 | 322.0 | 1 | 136.7 | −8 | 42.5 | −8 | 230.0 | −2 | 18.5 | −7 |

| 1991–2021 | 325.0 | 126.4 | 38.9 | 226.0 | 17.2 | ||||||

| Esik River—Esik City | 1955–1990 | 157.0 | −6 | 60.5 | −9 | 38.5 | −3 | 110.0 | −13 | 35.0 | 11 |

| 1991–2021 | 147.0 | 55.1 | 37.5 | 96.0 | 39.0 | ||||||

| Turgen River—Turgen Village | 1955–1990 | 222.0 | 3 | 43.0 | −11 | 19.4 | −13 | 158.0 | 4 | 12.3 | −16 |

| 1991–2021 | 228.0 | 38.3 | 16.8 | 164.0 | 10.2 | ||||||

| Shilik River—Malybai Village | 1955–1990 | 1043.0 | 43 | 362.5 | −0.002 | 19.0 | 0 | 776.0 | 68 | 2.4 | −41 |

| 1991–2021 | 1492.0 | 362.6 | 19.0 | 1306.0 | 1.5 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Akzharkynova, A.N.; Iskakov, B.; Iskaliyeva, G.; Sydyk, N.; Abdrakhimov, R.; Amangeldi, A.A.; Merekeyev, A.; Chigrinets, A. Climate-Driven Cryospheric Changes and Their Impacts on Glacier Runoff Dynamics in the Northern Tien Shan. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010063

Akzharkynova AN, Iskakov B, Iskaliyeva G, Sydyk N, Abdrakhimov R, Amangeldi AA, Merekeyev A, Chigrinets A. Climate-Driven Cryospheric Changes and Their Impacts on Glacier Runoff Dynamics in the Northern Tien Shan. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkzharkynova, Aigul N., Berik Iskakov, Gulnara Iskaliyeva, Nurmakhambet Sydyk, Rustam Abdrakhimov, Alima A. Amangeldi, Aibek Merekeyev, and Aleksandr Chigrinets. 2026. "Climate-Driven Cryospheric Changes and Their Impacts on Glacier Runoff Dynamics in the Northern Tien Shan" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010063

APA StyleAkzharkynova, A. N., Iskakov, B., Iskaliyeva, G., Sydyk, N., Abdrakhimov, R., Amangeldi, A. A., Merekeyev, A., & Chigrinets, A. (2026). Climate-Driven Cryospheric Changes and Their Impacts on Glacier Runoff Dynamics in the Northern Tien Shan. Atmosphere, 17(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010063