Author Contributions

H.W. (Hui Wang): conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. Y.D.: software, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. W.L.: validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. H.W. (Haitao Wang): validation, writing—review and editing. X.Z.: methodology, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Structure and detailed dimensions of the local model. (a) Ortho-three axonometric view; (b) vertical view; (c) front elevation.

Figure 1.

Structure and detailed dimensions of the local model. (a) Ortho-three axonometric view; (b) vertical view; (c) front elevation.

Figure 2.

Axial velocity distribution below the air intake of dust removal hood under different air volume.

Figure 2.

Axial velocity distribution below the air intake of dust removal hood under different air volume.

Figure 3.

Plane velocity vector diagram with z = 5 m and y = 2.5 m at different air volumes. (a) Air volume 200,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (b) air volume 200,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (c) air volume 300,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (d) air volume 300,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (e) air volume 400,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (f) air volume 400,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (g) air volume 500,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (h) air volume 500,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (i) cross-sectional schematic diagram.

Figure 3.

Plane velocity vector diagram with z = 5 m and y = 2.5 m at different air volumes. (a) Air volume 200,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (b) air volume 200,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (c) air volume 300,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (d) air volume 300,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (e) air volume 400,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (f) air volume 400,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (g) air volume 500,000 m3/h, z = 5 m plane; (h) air volume 500,000 m3/h, y = 2.5 m plane; (i) cross-sectional schematic diagram.

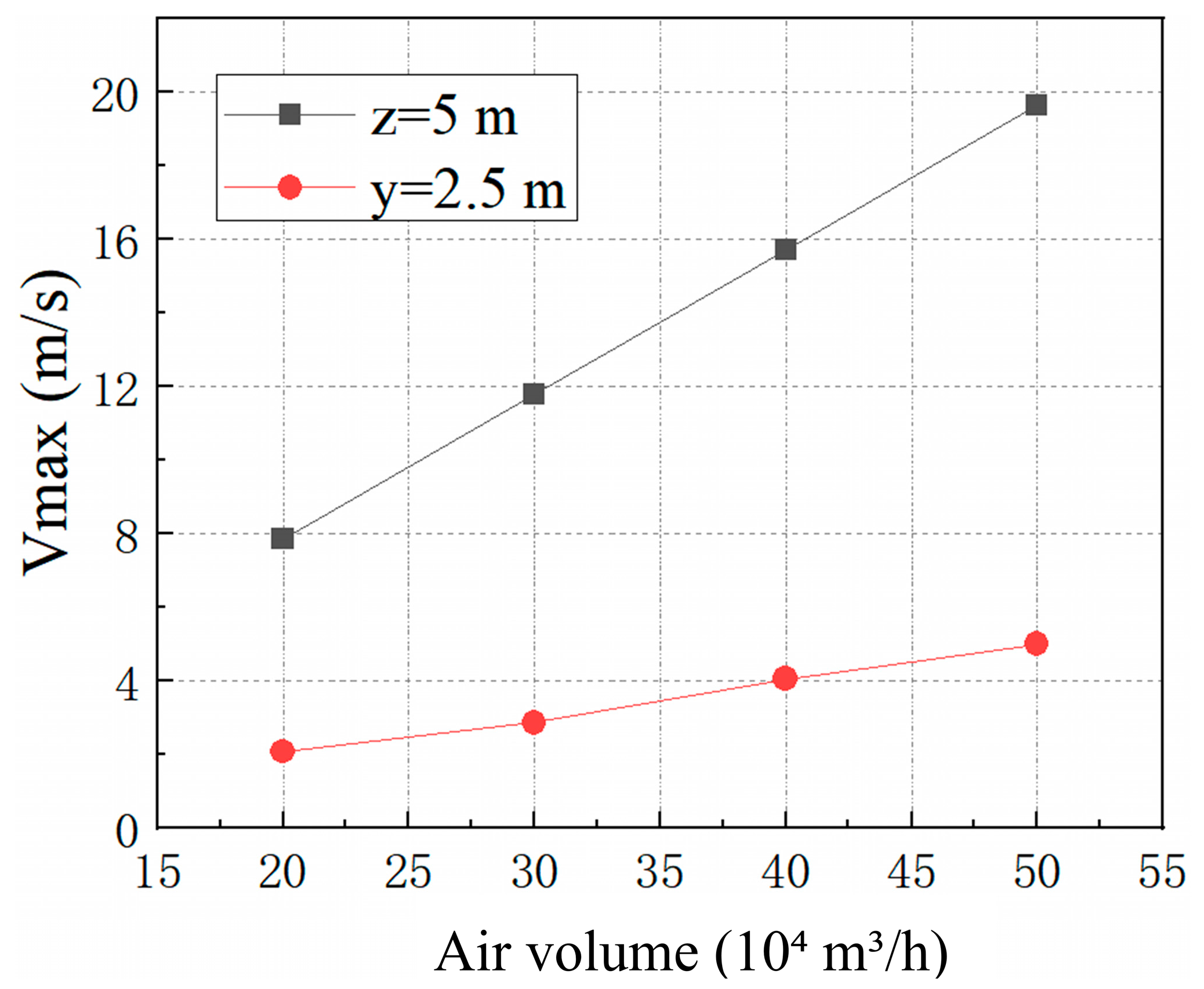

Figure 4.

Maximum velocity on the plane of z = 5 m and y = 2.5 m under different air volume.

Figure 4.

Maximum velocity on the plane of z = 5 m and y = 2.5 m under different air volume.

Figure 5.

Z = 5 plane velocity cloud diagram under different air volume. (a) Air volume 200,000 m3/h; (b) air volume 300,000 m3/h; (c) air volume 400,000 m3/h; (d) air volume 500,000 m3/h.

Figure 5.

Z = 5 plane velocity cloud diagram under different air volume. (a) Air volume 200,000 m3/h; (b) air volume 300,000 m3/h; (c) air volume 400,000 m3/h; (d) air volume 500,000 m3/h.

Figure 6.

Particle trajectory under different air volumes. (a) Air volume 200,000 m3/h; (b) air volume 300,000 m3/h; (c) air volume 400,000 m3/h; (d) air volume 500,000 m3/h.

Figure 6.

Particle trajectory under different air volumes. (a) Air volume 200,000 m3/h; (b) air volume 300,000 m3/h; (c) air volume 400,000 m3/h; (d) air volume 500,000 m3/h.

Figure 7.

Particle size capture efficiency at 300,000 m3/h dust removal air volume. (a) Capture efficiency of different particle sizes; (b) trajectory of 40 μm particulate matter.

Figure 7.

Particle size capture efficiency at 300,000 m3/h dust removal air volume. (a) Capture efficiency of different particle sizes; (b) trajectory of 40 μm particulate matter.

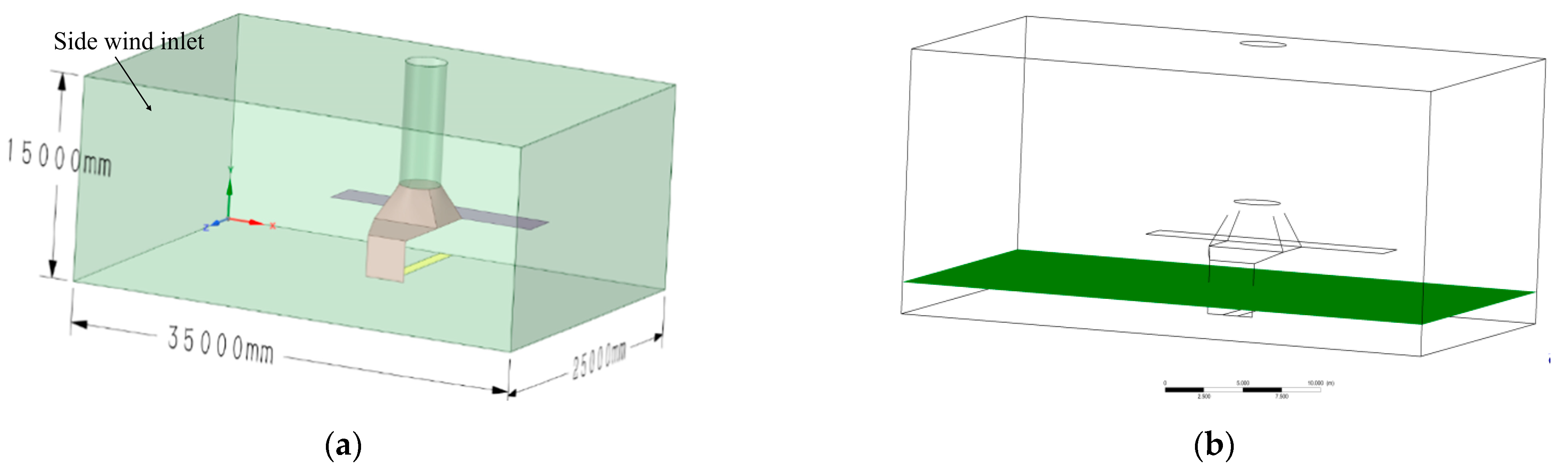

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of crosswind and target area. (a) Location of the side air inlet; (b) the planar spatial distribution of y = 1.8 m.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of crosswind and target area. (a) Location of the side air inlet; (b) the planar spatial distribution of y = 1.8 m.

Figure 9.

Particle distribution under different crosswinds. (a) Distribution of plane velocity field at y = 1.8 m under different crosswinds; (b) particle trajectory under different crosswind speeds.

Figure 9.

Particle distribution under different crosswinds. (a) Distribution of plane velocity field at y = 1.8 m under different crosswinds; (b) particle trajectory under different crosswind speeds.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of adding 1.4 m side baffle.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of adding 1.4 m side baffle.

Figure 11.

Velocity field distribution in plane y = 1.8 m. (a) Case 1; (b) case 2.

Figure 11.

Velocity field distribution in plane y = 1.8 m. (a) Case 1; (b) case 2.

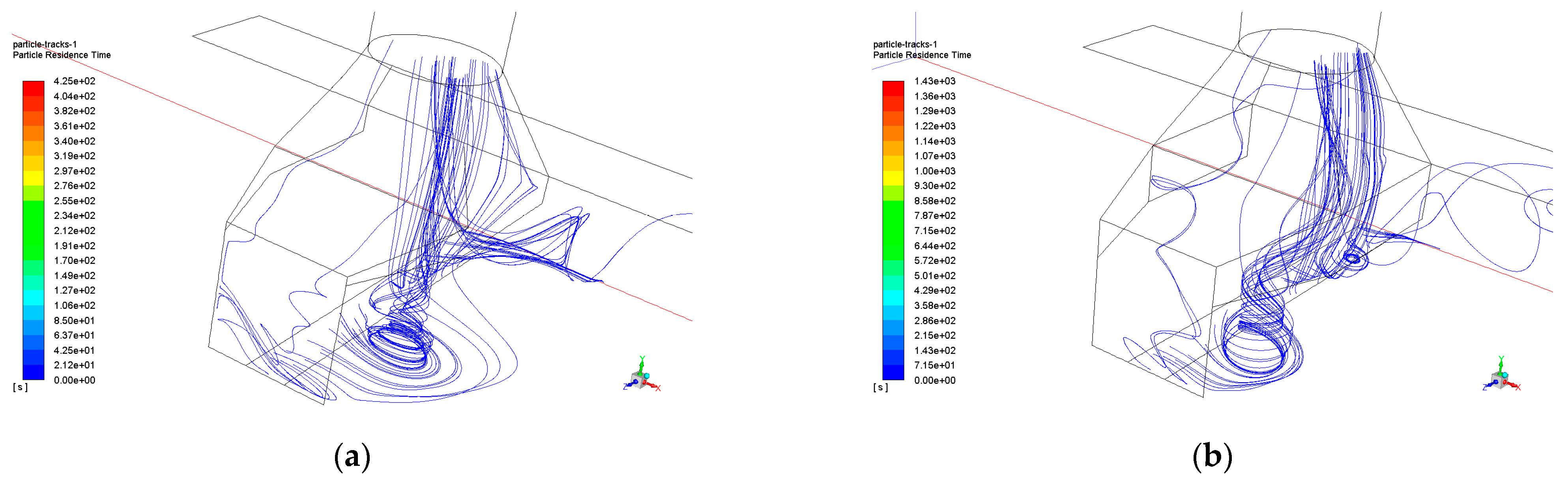

Figure 12.

Particle trajectory under case 1 and case 2. (a) Case 1; (b) case 2.

Figure 12.

Particle trajectory under case 1 and case 2. (a) Case 1; (b) case 2.

Figure 13.

Case 3 and case 4 model diagram. (a) Case 3 (the overcoat); (b) case 4 (with flanges on both sides).

Figure 13.

Case 3 and case 4 model diagram. (a) Case 3 (the overcoat); (b) case 4 (with flanges on both sides).

Figure 14.

Velocity field distribution at z = 5 m: (a) case 3, (b) case 4.

Figure 14.

Velocity field distribution at z = 5 m: (a) case 3, (b) case 4.

Figure 15.

Particle trajectory. (a) Case 3; (b) case 4.

Figure 15.

Particle trajectory. (a) Case 3; (b) case 4.

Figure 16.

Velocity field distribution in plane y = 1.8 m. (a) Case 3; (b) case 4.

Figure 16.

Velocity field distribution in plane y = 1.8 m. (a) Case 3; (b) case 4.

Figure 17.

Case 5 and case 6 model diagram. (a) Case 5; (b) case 6.

Figure 17.

Case 5 and case 6 model diagram. (a) Case 5; (b) case 6.

Figure 18.

Particle distribution under case 5 condition: (a) velocity field at y = 1.8 m; (b) particle trajectory.

Figure 18.

Particle distribution under case 5 condition: (a) velocity field at y = 1.8 m; (b) particle trajectory.

Figure 19.

Particle distribution under case 6 condition: (a) velocity field at y = 1.8 m; (b) particle trajectory.

Figure 19.

Particle distribution under case 6 condition: (a) velocity field at y = 1.8 m; (b) particle trajectory.

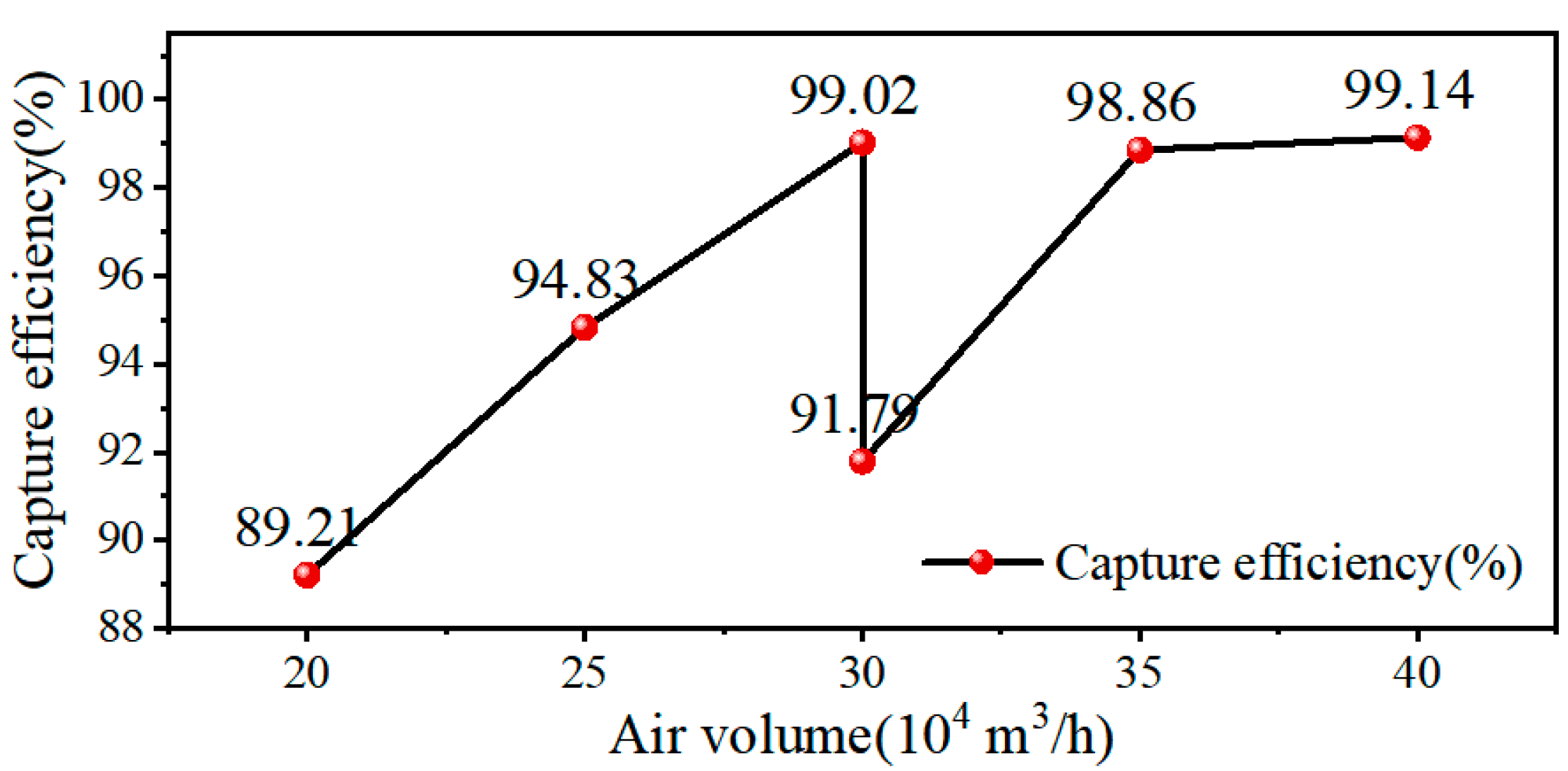

Figure 20.

The relationship between capture efficiency and air volume.

Figure 20.

The relationship between capture efficiency and air volume.

Table 1.

Boundary conditions.

Table 1.

Boundary conditions.

| Position | Boundary Condition | Temperature (°C) | Wind Speed (m/s) | DMP-Injection |

|---|

| Top glazing | Outflow | — | — | Escape |

| Lower sector window | Inlet | Set according to the Table 2 | Set according to the Table 2 | Escape |

| Iron water ditch | Wall | Ejection: 1100 °C, molten iron slides along the flow direction 0.03 m/s | — | Reflect |

| Residual iron: 750 °C | — |

| adiabat | — |

| Other walls | Set according to the Table 3 | — |

| Top of dust collector | Inlet | 55 | Set according to air volume | Trap |

Table 2.

Wind speed and temperature of the bottom air inlet door and window.

Table 2.

Wind speed and temperature of the bottom air inlet door and window.

| | North Side Gate | North Window | West Window | Eastern Window |

|---|

| Wind speed (m/s) | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.15 | 0.55 |

| Temperature (°C) | 30 | 31 | 31 | 30 |

Table 3.

Temperature of each wall in the factory room.

Table 3.

Temperature of each wall in the factory room.

| Position | Temperature (°C) | Position | Temperature (°C) |

|---|

| High furnace walls | 40 | Dust removal cover | 55 |

| Plant wall | 35 | Dust removal pipe | 40 |

| Top of plant | 40 | Iron gutter cover | 110 |

| Iron water ditch | 750~1100 | Slag dip cover | 170 |

Table 4.

Dust removal efficiency of dust collector under different air volume.

Table 4.

Dust removal efficiency of dust collector under different air volume.

| Air volume (10,000 m3/h) | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 |

| Collection efficiency (%) | 96.87 | 98.00 | 99.01 | 99.67 |

Table 5.

Influence of crosswind on capture efficiency.

Table 5.

Influence of crosswind on capture efficiency.

| Dust Removal Air Volume (10,000 m3/h) | Side Wind (m/s) | Collection Efficiency (%) |

|---|

| 40 | 0.6 | 98.83 |

| 40 | 0.9 | 96.37 |

| 40 | 1.2 | 87.23 |

| 40 | 1.5 | 77.96 |

Table 6.

Optimization conditions of dust removal and its capture efficiency.

Table 6.

Optimization conditions of dust removal and its capture efficiency.

| | Side Panel Height (m) | Dust Collector Shape | Location of the Ejector Fan | Collection Efficiency (%) |

|---|

| Case 1 | 0.7 | normal | not have | 81.86 |

| Case 2 | 1.4 | normal | not have | 86.83 |

| Case 3 | 1.4 | big gown | not have | 93.82 |

| Case 4 | 1.4 | wing plates are provided on both sides | not have | 99.14 |

| Case 5 | 1.4 | normal | behind | 95.39 |

| Case 6 | 1.4 | normal | front | 85.26 |

Table 7.

Optimization simulation results of dust removal air volume.

Table 7.

Optimization simulation results of dust removal air volume.

| Side Wind (m/s) | Dust Removal Air Volume (104 m3/h) | Collection Efficiency (%) |

|---|

| 1.5 | 40 | 99.14 |

| 1.5 | 35 | 98.86 |

| 1.5 | 30 | 91.79 |

| 0.9 | 30 | 99.02 |

| 0.9 | 25 | 94.83 |

| 0.9 | 20 | 89.21 |