Comparative Study of the Morphology and Chemical Composition of Airborne Brake Particulate Matter from a Light-Duty Automotive and a Rail Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testing Conditions

2.2. TEM and EDX Analyses

2.3. SEM Analysis

2.4. Morphological Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

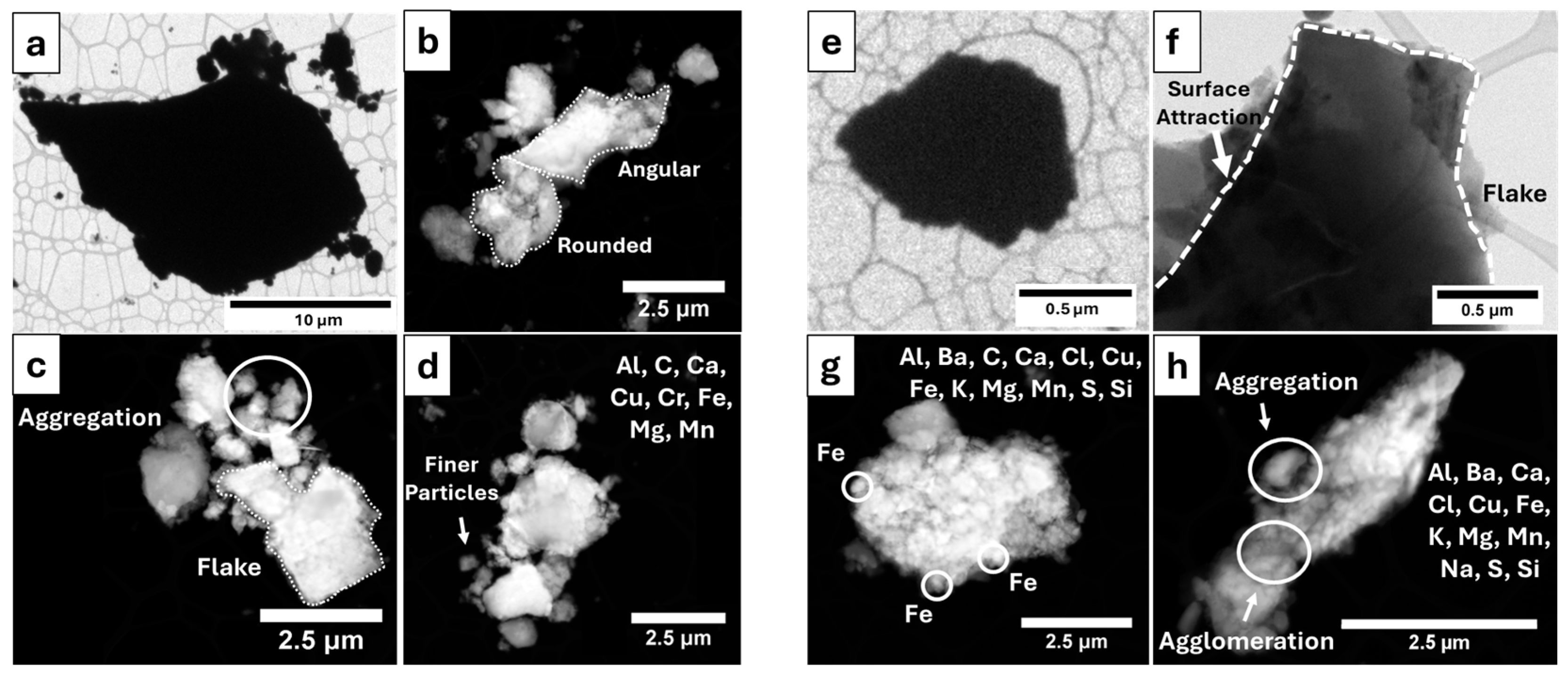

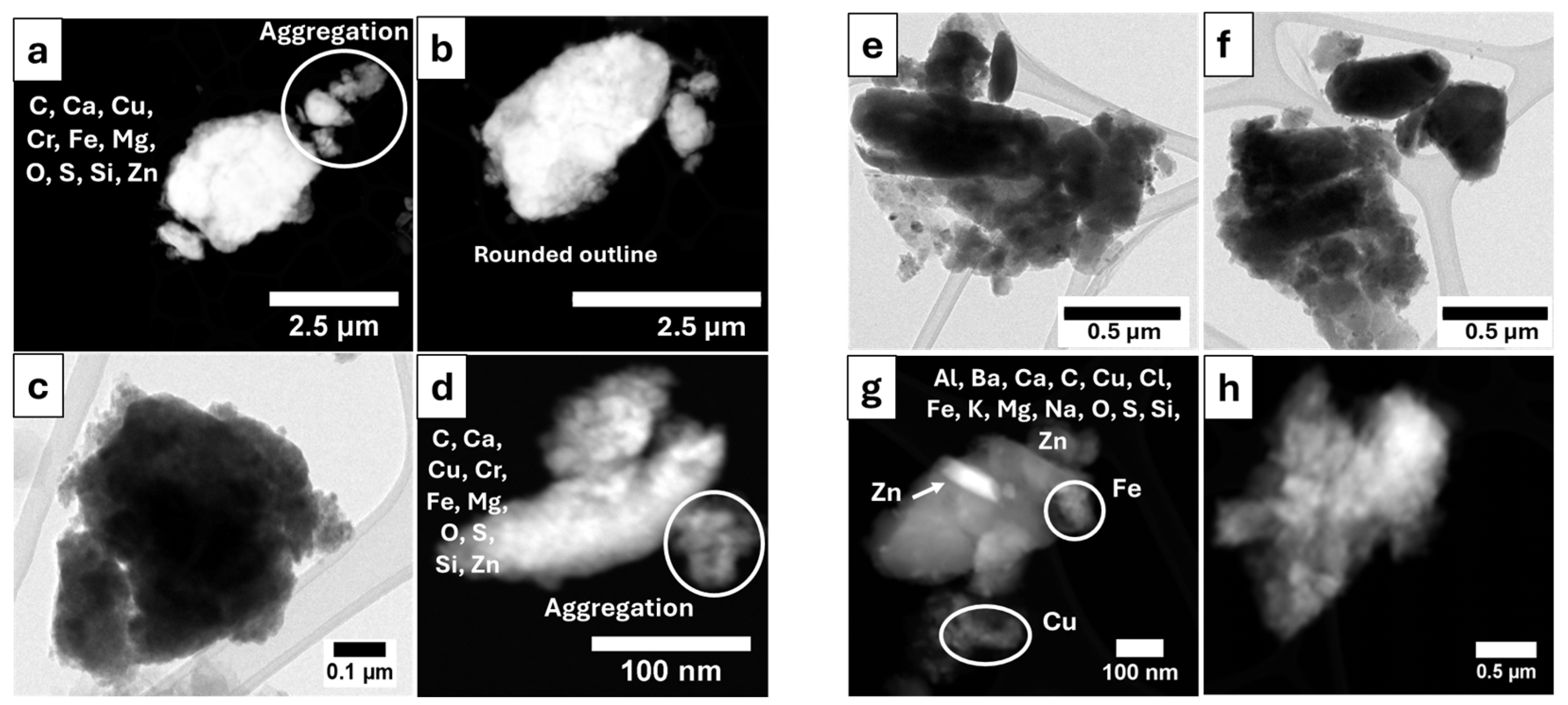

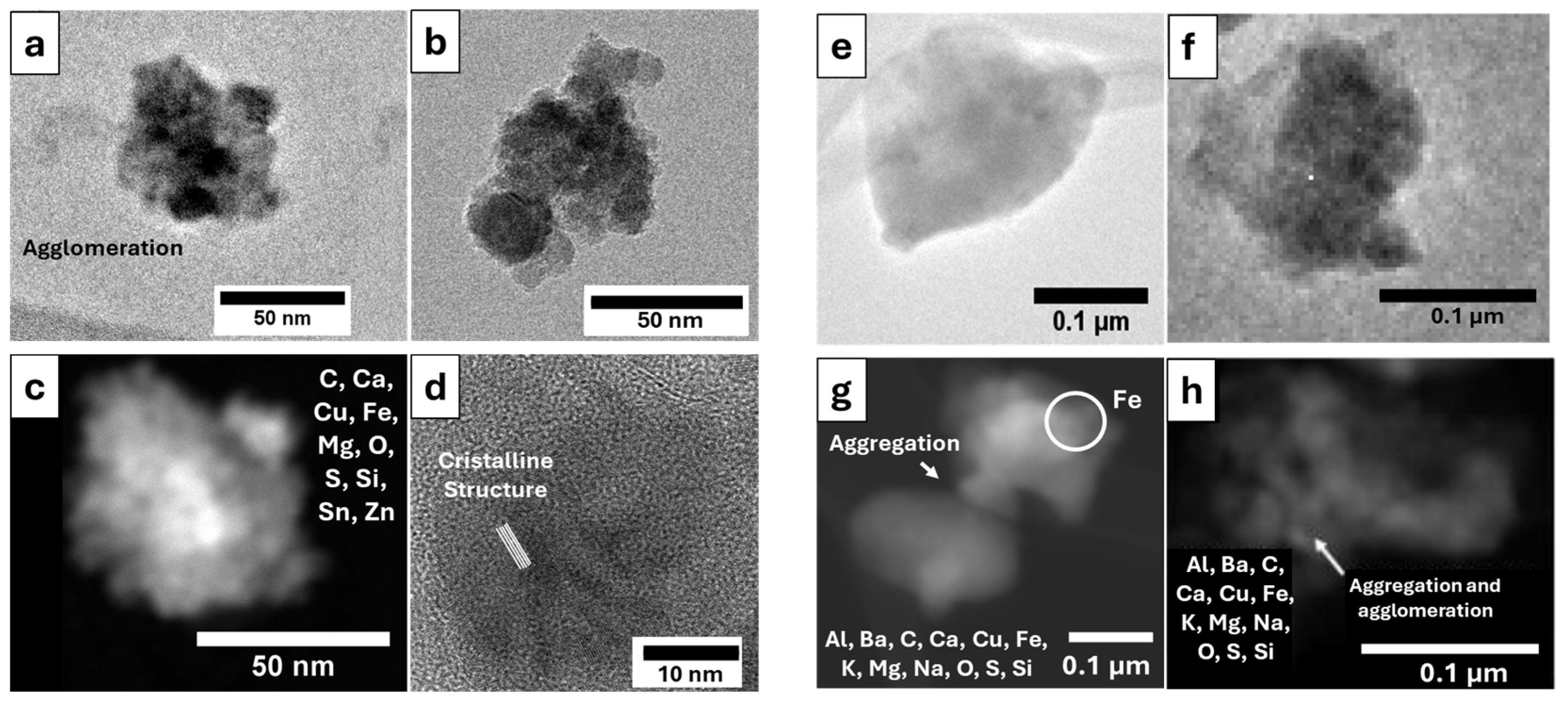

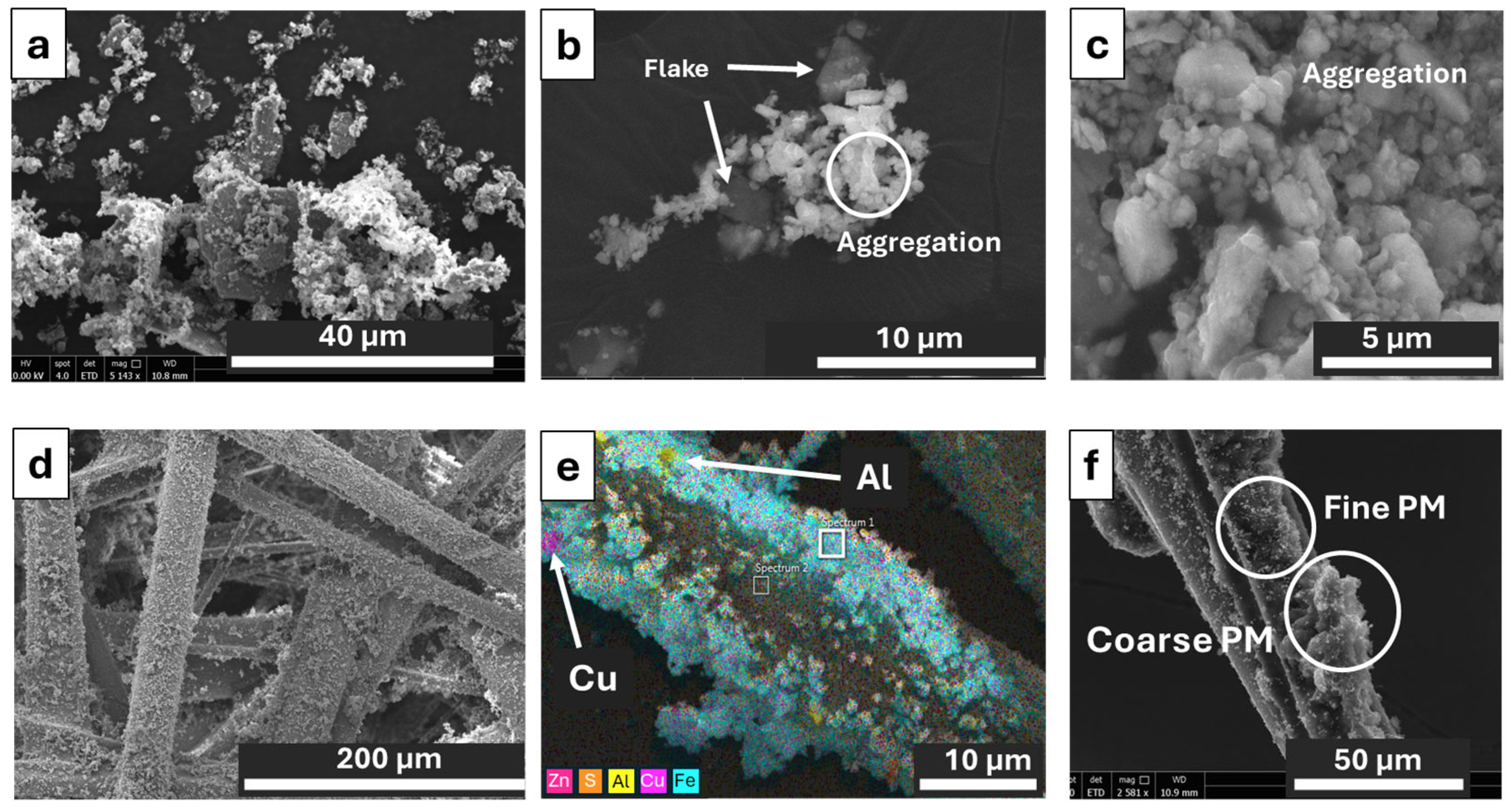

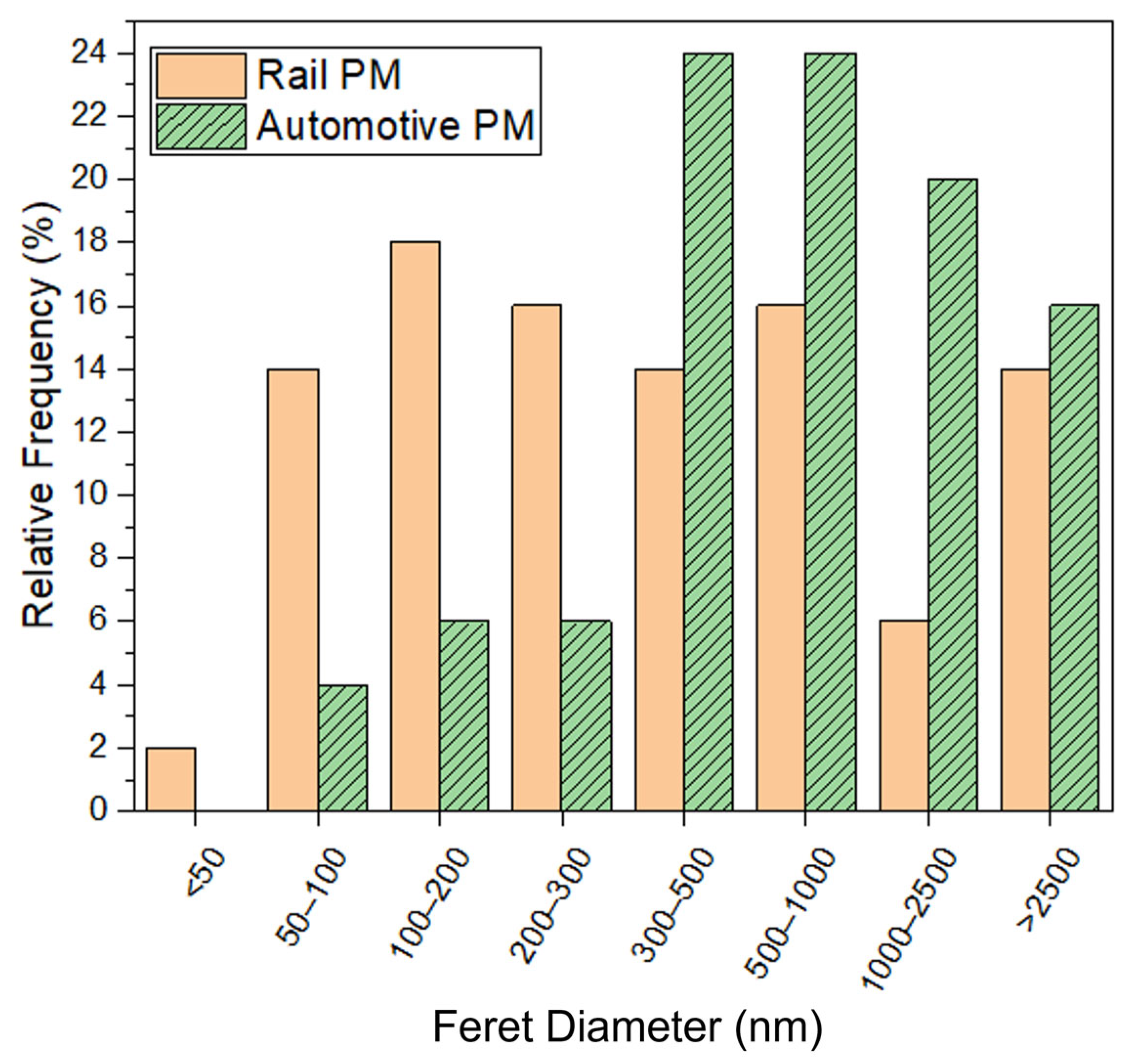

- The morphological analysis revealed that PM particles primarily form aggregates in both samples, with coarse, fine, and ultrafine sizes. However, differences were observed in particle shape, with larger, angular flakes found in automotive PM and smaller, rounded particles in rail PM. In the former, 16% of particles exceeded 2.5 µm, whereas the latter showed particles down to 50 nm in diameter. Past investigations suggested that disc temperature affects the PM shape, resulting in the formation of smaller, smoother, and more spherical particles in the rail PM. Although temperature was not directly measured here, this assumption aligns with trends reported in earlier studies.

- -

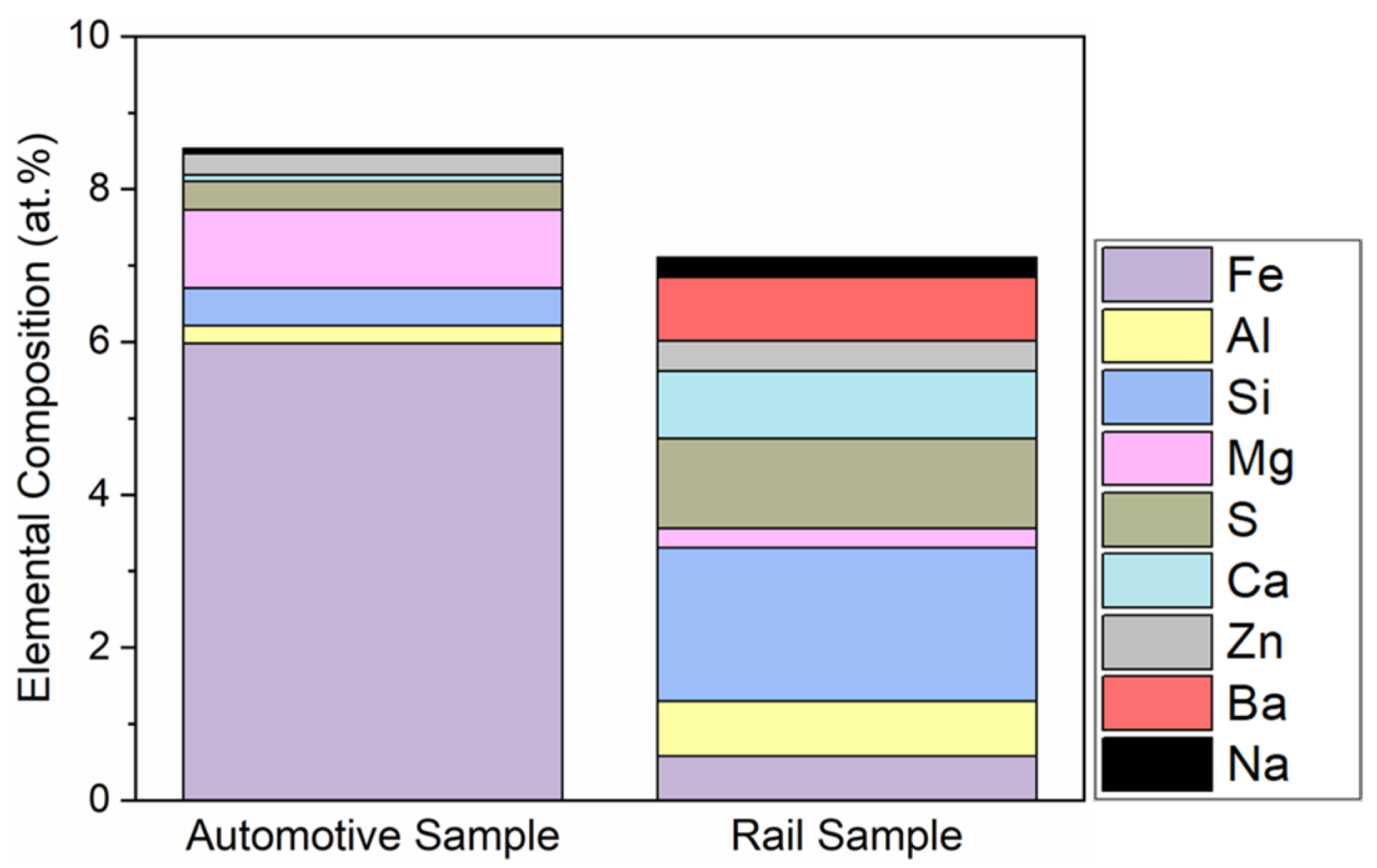

- EDX investigations revealed that particles are mainly composed of oxygen (~65 at.%) and carbon (~25 at.%). The chemical composition of brake PM from each sample is consistent with the elements from their respective brake pads and discs. Iron is the most abundant element in the automotive PM (7 at.%), followed by magnesium (1 at.%). Conversely, the rail PM showed lower iron (0.6 at.%) and higher aluminium (0.7 at.%) and calcium (0.8 at.%), with a broader non-C/O composition.

- -

- SEM-EDX analysis on automotive PM proved that TEM-EDX preparation did not affect the natural formation of brake PM in the coarse and fine size ranges. Fine and ultrafine PM adhered to the filter fibres better than coarse PM. The strong match observed between TEM observations and SEM results suggests that this methodology can be adopted for reliable characterisation of particle emissions in real-world scenarios.

- -

- The practical implication of this work is the necessity to account for source-specific morphological and chemical characteristics of particulate matter for the development of future non-exhaust emission regulations.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Churchill, S.; Misra, A.; Brown, P.; Del Vento, S.; Karagianni, E.; Murrells, T.; Passant, N.; Richardson, J.; Richmond, B.; Smith, H. UK Informative Inventory Report (1990 to 2019); Ricardo Energy Environment: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Xu, X.; Chu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Air particulate matter and cardiovascular disease: The epidemiological, biomedical and clinical evidence. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lau, A.K.; Lin, C.Q.; Chuang, Y.C.; Chan, J.; Jiang, W.K.; Tam, T.; Yeoh, E.-K.; Chan, T.-C. Effect of long-term exposure to fine particulate matter on lung function decline and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Taiwan: A longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e114–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.A., III; Burnett, R.T.; Thun, M.J.; Calle, E.E.; Krewski, D.; Ito, K.; Thurston, G.D. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 2002, 287, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Im, U.; Geels, C.; Palacios-Peña, L.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P. Contribution of fine particulate matter to present and future premature mortality over Europe: A non-linear response. Environ. Int. 2021, 153, 106517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M.; Im, U.; Brandt, J.; Palacios-Peña, L.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P. Isolating the climate change impacts on air-pollution-related-pathologies over central and southern Europe—A modelling approach on cases and costs. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 9385–9398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byčenkienė, S.; Khan, A.; Bimbaitė, V. Impact of PM2.5 and PM10 emissions on changes of their concentration levels in Lithuania: A case study. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authority, G.L. Air Pollution Monitoring Data in London: 2016 to 2020; Greater London Authority: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oroumiyeh, F.; Zhu, Y. Brake and tire particles measured from on-road vehicles: Effects of vehicle mass and braking intensity. Atmos. Environ. X 2021, 12, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaqiang, E.; Xu, W.; Ma, Y.; Tan, D.; Peng, Q.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L. Soot formation mechanism of modern automobile engines and methods of reducing soot emissions: A review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 235, 107373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Dave, K.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Tu, R. Exhaust and non-exhaust emissions from conventional and electric vehicles: A comparison of monetary impact values. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M.; Jones, A.M.; Gietl, J.; Yin, J.; Green, D.C. Estimation of the contributions of brake dust, tire wear, and resuspension to nonexhaust traffic particles derived from atmospheric measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6523–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Sokhi, R.; Ravindra, K.; Mao, H.; Prain, H.D.; Bull, I.D. Source apportionment of traffic emissions of particulate matter using tunnel measurements. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 77, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Long, W.; Xie, C.; Tian, H. After-Treatment Technologies for Emissions of Low-Carbon Fuel Internal Combustion Engines: Current Status and Prospects. Energies 2025, 18, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, H.; Tan, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Hao, L.; Du, T.; Niu, Z.; Ge, Y. A comprehensive review of tyre wear particles: Formation, measurements, properties, and influencing factors. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 297, 119597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feo, M.L.; Torre, M.; Tratzi, P.; Battistelli, F.; Tomassetti, L.; Petracchini, F.; Guerriero, E.; Paolini, V. Laboratory and on-road testing for brake wear particle emissions: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 100282–100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission, E. Commission Proposes New Euro 7 Standards to Reduce Pollutant Emissions From Vehicles and Improve Air Quality; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Duan, J. A comprehensive understanding of ambient particulate matter and its components on the adverse health effects based from epidemiological and laboratory evidence. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostro, B.; Hu, J.; Goldberg, D.; Reynolds, P.; Hertz, A.; Bernstein, L.; Kleeman, M.J. Associations of mortality with long-term exposures to fine and ultrafine particles, species and sources: Results from the California Teachers Study Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kaur, M.; Li, T.; Pan, F. Effect of different pollution parameters and chemical components of PM2.5 on health of residents of Xinxiang City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacino, A.; Haffner-Staton, E.; La Rocca, A.; Smith, J.; Fowell, M. Understanding the Challenges Associated with Soot-in-Oil From Diesel Engines: A Review Paper; SAE Intenational: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Madureira, J.; Slezakova, K.; Costa, C.; Pereira, M.C.; Teixeira, J.P. Assessment of indoor air exposure among newborns and their mothers: Levels and sources of PM10, PM2.5 and ultrafine particles at 65 home environments. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tanzeglock, L.; Tu, M.; Mo, J.; Okuda, T.; Pagels, J.; Wahlström, J. Mapping of friction, wear and particle emissions from high-speed train brakes. Wear 2025, 572, 206027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Jansson, A.; Olander, L.; Olofsson, U.; Sellgren, U. A pin-on-disc study of the rate of airborne wear particle emissions from railway braking materials. Wear 2012, 284, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liati, A.; Schreiber, D.; Lugovyy, D.; Gramstat, S.; Eggenschwiler, P.D. Airborne particulate matter emissions from vehicle brakes in micro-and nano-scales: Morphology and chemistry by electron microscopy. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 212, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namgung, H.-G.; Kim, J.-B.; Woo, S.-H.; Park, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, M.-S.; Bae, G.-N.; Park, D.; Kwon, S.-B. Generation of nanoparticles from friction between railway brake disks and pads. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 3453–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, H.L.; Nilsson, L.; Möller, L. Subway particles are more genotoxic than street particles and induce oxidative stress in cultured human lung cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 18, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Bao, J.; Lu, L.; Feng, X. Review on the friction and wear of brake materials. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2016, 8, 1687814016647300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternbeck, J.; Sjödin, Å.; Andréasson, K. Metal emissions from road traffic and the influence of resuspension—Results from two tunnel studies. Atmos. Environ. 2002, 36, 4735–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, U. A study of airborne wear particles generated from the train traffic—Block braking simulation in a pin-on-disc machine. Wear 2011, 271, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octau, C.; Meresse, D.; Watremez, M.; Schiffler, J.; Lippert, M.; Keirsbulck, L.; Dubar, L. Characterization of particulate matter emissions in urban train braking—An investigation of braking conditions influence on a reduced-scale device. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 18615–18631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, R.; Zhang, J.; Nie, X.; Tjong, J.; Matthews, D. Wear mechanism evolution on brake discs for reduced wear and particulate emissions. Wear 2020, 452, 203283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, U.; Olander, L. On the identification of wear modes and transitions using airborne wear particles. Tribol. Int. 2013, 59, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutuianu, M.; Bonnel, P.; Ciuffo, B.; Haniu, T.; Ichikawa, N.; Marotta, A.; Pavlovic, J.; Steven, H. Development of the World-wide harmonized Light duty Test Cycle (WLTC) and a possible pathway for its introduction in the European legislation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 40, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascoet, M.; Adamczak, L. At source brake dust collection system. Results Eng. 2020, 5, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Railway Technology. Réseau Express Régional (RER), Paris. 2012. Available online: https://www.railway-technology.com/projects/reseau-express-regional-rer-france/?cf-view (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Tanzeglock, L. Particle Emissions of Train Brakes; Lund Univerity Publications: Lund, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, A.; Ischia, G.; Straffelini, G.; Gialanella, S. A new sample preparation protocol for SEM and TEM particulate matter analysis. Ultramicroscopy 2021, 230, 113365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, S.A.; La Rocca, A.; Haffner-Staton, E.; Rance, G.A.; Fay, M.W.; Brough, R.J.; Malizia, S. Comparative nanostructure analysis of gasoline turbocharged direct injection and diesel soot-in-oil with carbon black. Carbon 2018, 139, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner-Staton, E. Development of High-Throughput Electron Tomography for 3D Morphological Characterisation of Soot Nanoparticles; University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, P.E.; Najab, J. Mann-whitney U test. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlström, J.; Olander, L.; Olofsson, U. Size, shape, and elemental composition of airborne wear particles from disc brake materials. Tribol. Lett. 2010, 38, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.-H.; Jang, H.; Na, M.Y.; Chang, H.J.; Lee, S. Characterization of brake particles emitted from non-asbestos organic and low-metallic brake pads under normal and harsh braking conditions. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 278, 119089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, D.; Hamatschek, C.; Augsburg, K.; Weigelt, T.; Prahst, A.; Gramstat, S. Testing of alternative disc brakes and friction materials regarding brake wear particle emissions and temperature behavior. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, B.; Shen, Q.; Xiao, G. Numerical simulation of the frictional heat problem of subway brake discs considering variable friction coefficient and slope track. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 130, 105794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Wasif-Ruiz, T.; Suárez-Bertoa, R.; Sánchez-Martín, J.A.; Barrios-Sánchez, C.C. Direct measurement of brake wear particles from a light-duty vehicle under real-world driving conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 2551–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukutschová, J.; Moravec, P.; Tomášek, V.; Matějka, V.; Smolík, J.; Schwarz, J.; Seidlerová, J.; Šafářová, K.; Filip, P. On airborne nano/micro-sized wear particles released from low-metallic automotive brakes. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Zhang, S.; Tan, D.; Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Xia, S. Improvement of strength and wear resistance of stir cast SiCp/Al brake disc through friction stir processing. Wear 2025, 582–583, 206343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Du, J.; Ji, D.; Shen, M. Size effect of CrFe particles on tribological behavior and airborne particle emissions of copper metal matrix composites. Tribol. Int. 2023, 183, 108376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, F.J.; Fussell, J.C. Size, source and chemical composition as determinants of toxicity attributable to ambient particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 60, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari Nejad, S.; Takechi, R.; Mullins, B.J.; Giles, C.; Larcombe, A.N.; Bertolatti, D.; Rumchev, K.; Dhaliwal, S.; Mamo, J. The effect of diesel exhaust exposure on blood–brain barrier integrity and function in a murine model. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoratos, T.; Martini, G. Brake wear particle emissions: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 2491–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Iwata, A.; Yamanaka, H.; Ogane, K.; Mori, T.; Honda, A.; Takano, H.; Okuda, T. Characteristic Fe and Cu compounds in particulate matter from subway premises in Japan and their potential biological effects. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2024, 24, 230156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshon, J.M.; Shardell, M.; Alles, S.; Powell, J.L.; Squibb, K.; Ondov, J.; Blaisdell, C.J. Elevated ambient air zinc increases pediatric asthma morbidity. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heal, M.R.; Hibbs, L.R.; Agius, R.M.; Beverland, I.J. Total and water-soluble trace metal content of urban background PM10, PM2.5 and black smoke in Edinburgh, UK. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 1417–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PM Size | Automotive Sample | Rail Sample | Filter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse (10–2.5 µm) | ||||

| Most common Least common |  | Fe Cu, Si, S Al, Mn Ca, Cr, Mg, Mo | Al, Ba, Ca, Cu, Mg, Si, Fe, S Zn Sr | Fe Cu, Al S |

| Fine (2.5–0.1 µm) | ||||

| Most common Least common |  | Fe Mg, Al, S, Si, Cu, Sn Ca, Cr, Cu, Zn | Al, Ca, Cu, Mg, Na, Si K, S Ba, Cl, Fe, Zn Sr | Fe Al, Zn |

| Ultrafine (<0.1 µm) | ||||

| Most common Least common |  | Fe Mg, S, Si, Sn Cr, Cu, Zn | Al, Ba, Ca, Mg, Na, Si Fe, Cu, S K | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pacino, A.; La Rocca, A.; Brookes, H.I.; Haffner-Staton, E.; Fay, M.W. Comparative Study of the Morphology and Chemical Composition of Airborne Brake Particulate Matter from a Light-Duty Automotive and a Rail Sample. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010034

Pacino A, La Rocca A, Brookes HI, Haffner-Staton E, Fay MW. Comparative Study of the Morphology and Chemical Composition of Airborne Brake Particulate Matter from a Light-Duty Automotive and a Rail Sample. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010034

Chicago/Turabian StylePacino, Andrea, Antonino La Rocca, Harold Ian Brookes, Ephraim Haffner-Staton, and Michael W. Fay. 2026. "Comparative Study of the Morphology and Chemical Composition of Airborne Brake Particulate Matter from a Light-Duty Automotive and a Rail Sample" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010034

APA StylePacino, A., La Rocca, A., Brookes, H. I., Haffner-Staton, E., & Fay, M. W. (2026). Comparative Study of the Morphology and Chemical Composition of Airborne Brake Particulate Matter from a Light-Duty Automotive and a Rail Sample. Atmosphere, 17(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010034