Characteristics of Atmospheric CO2 at Shangri-La Regional Atmospheric Background Station in Southwestern China: Insights from Recent Observations (2019–2022)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

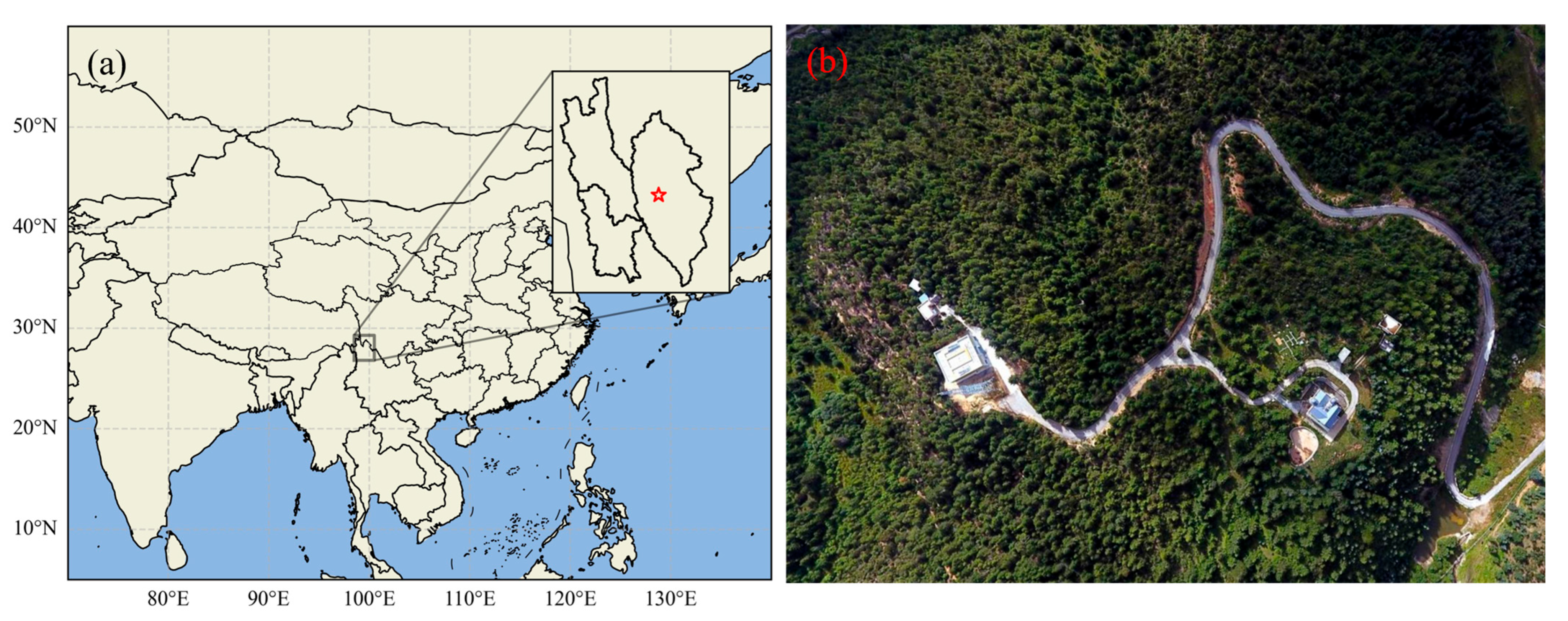

2.1. Sampling Site and Measurement System

2.2. Data Processing and Analysis

2.2.1. Background Extraction

2.2.2. Backward Trajectory Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

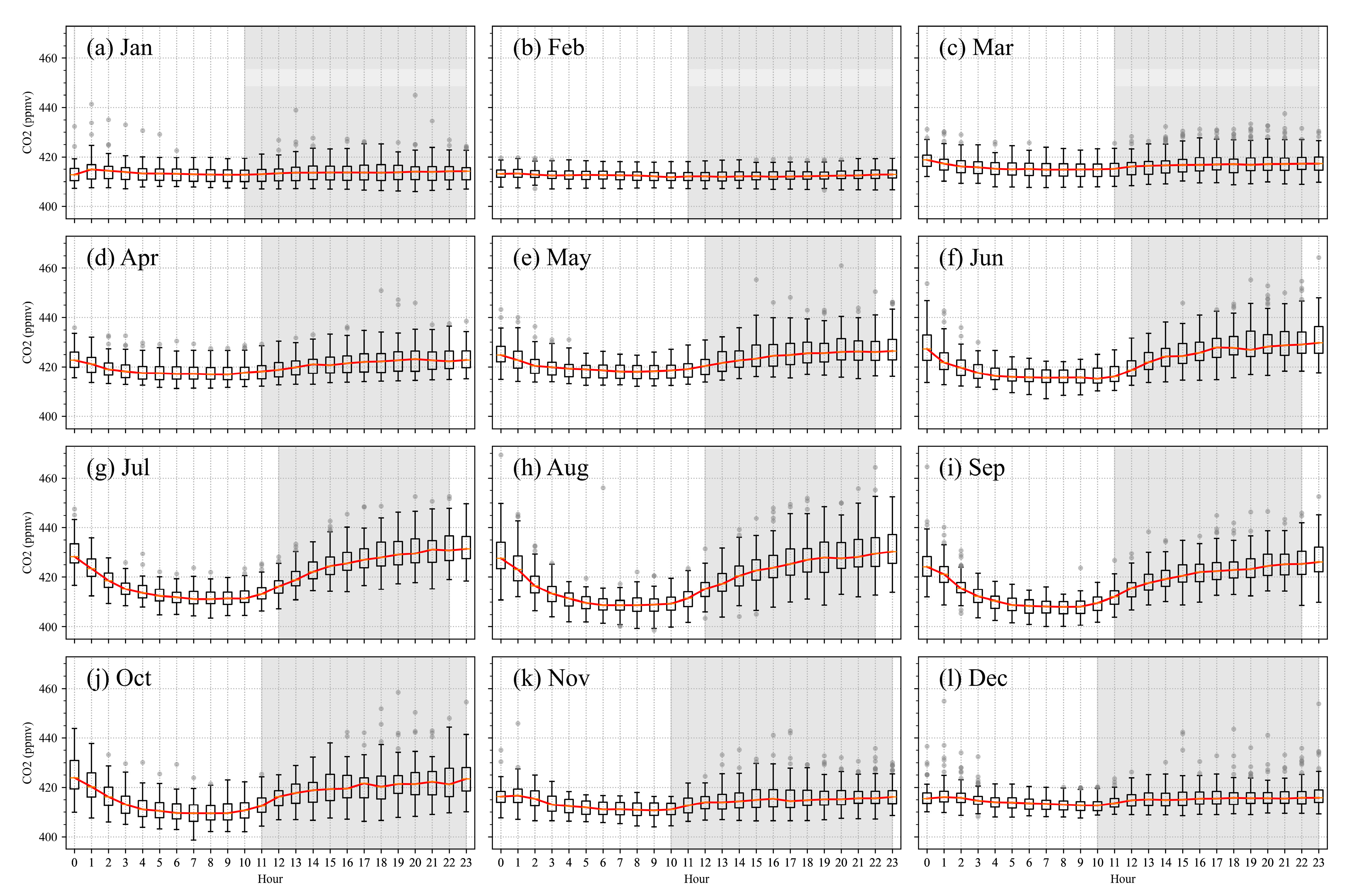

3.1. Temporal Distribution of Observed CO2

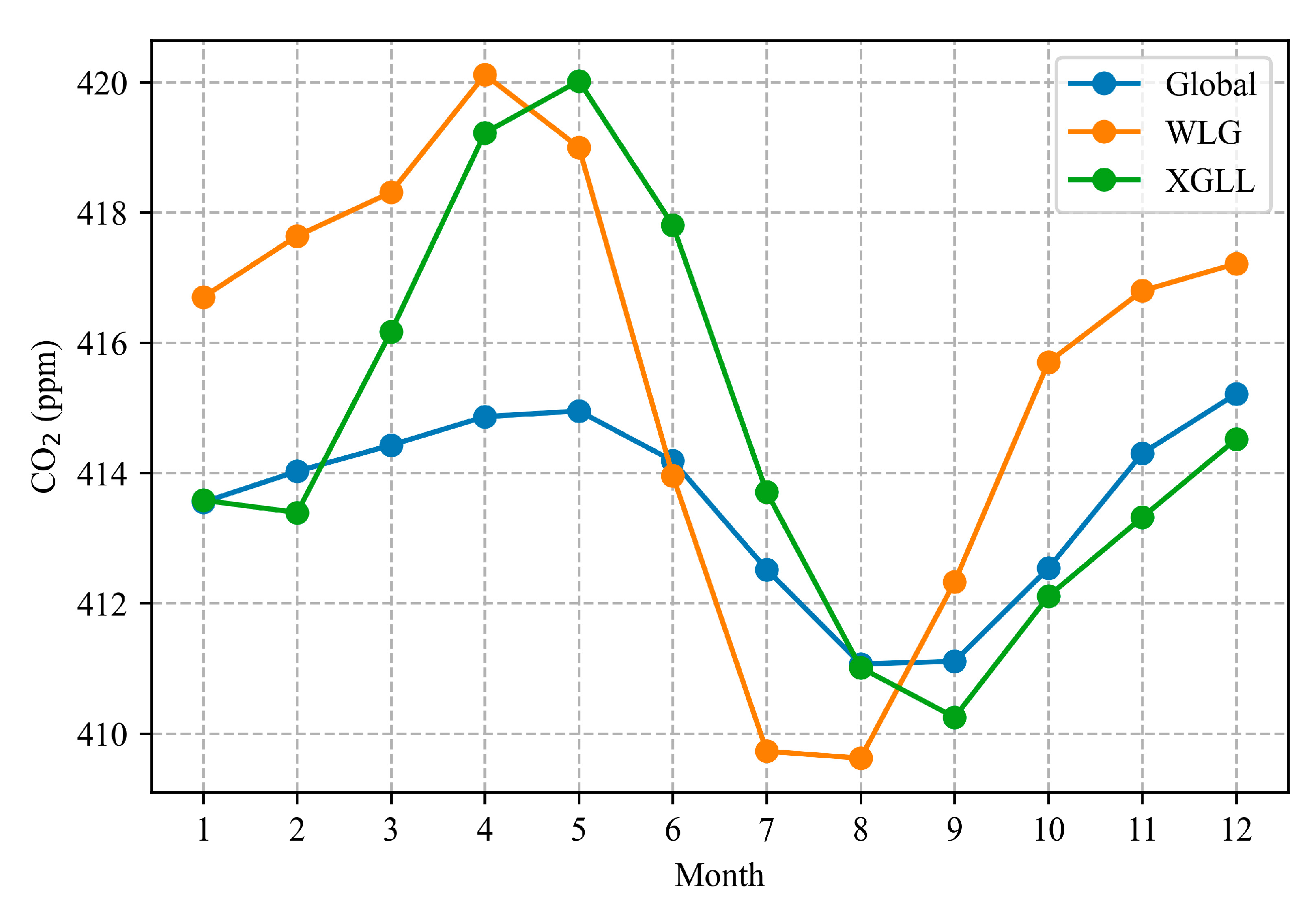

3.2. Filtered Background CO2 Observation

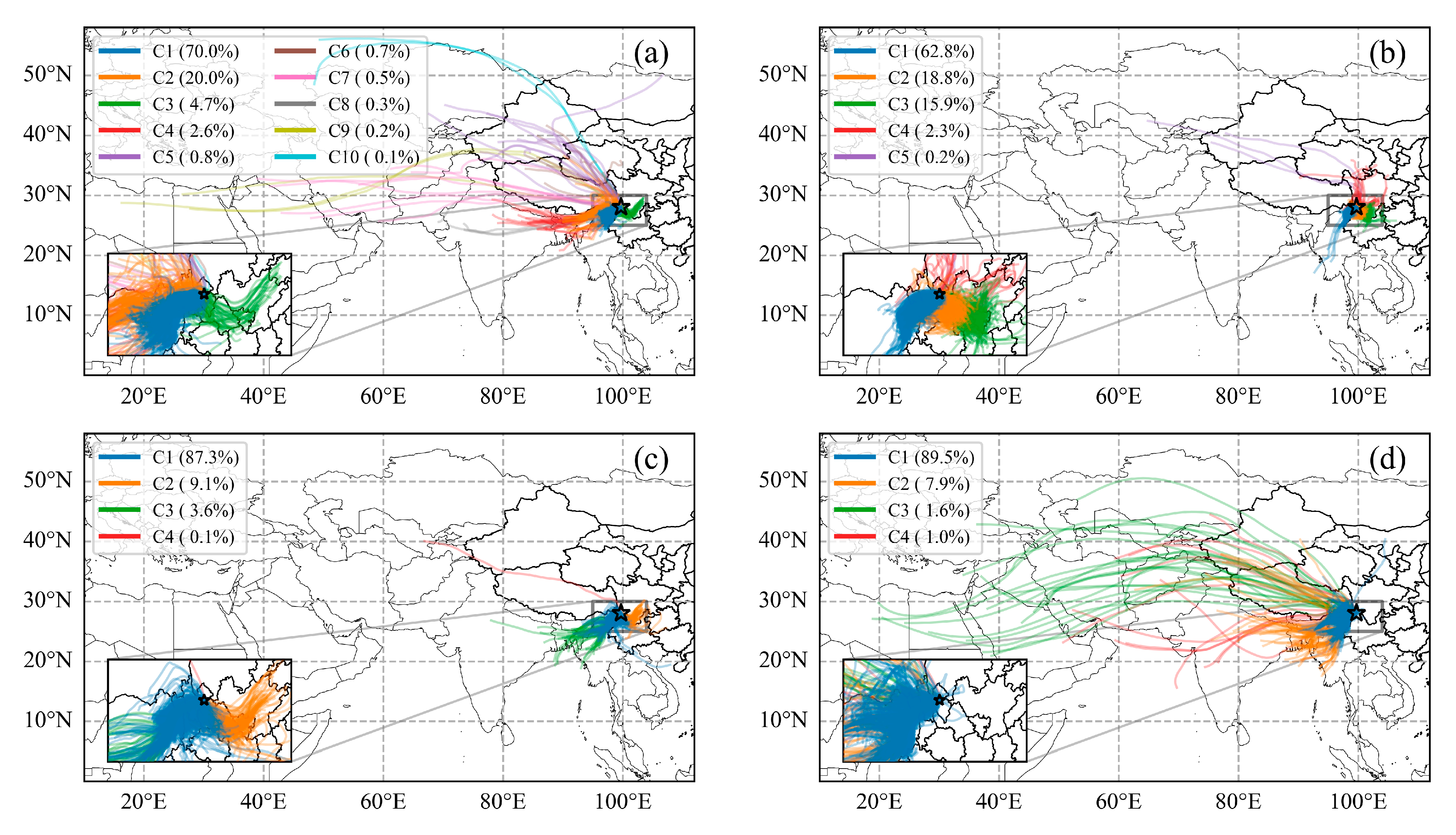

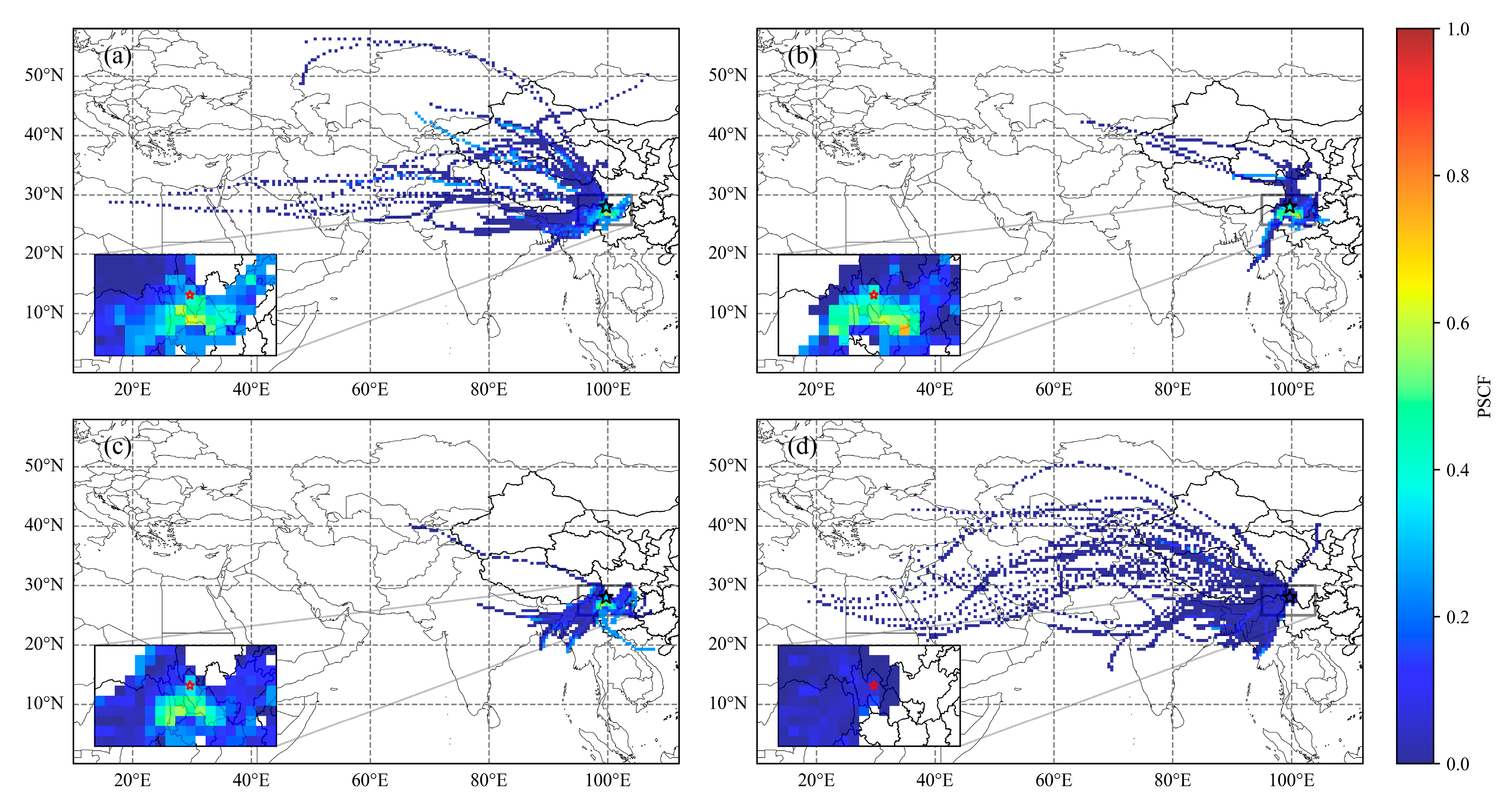

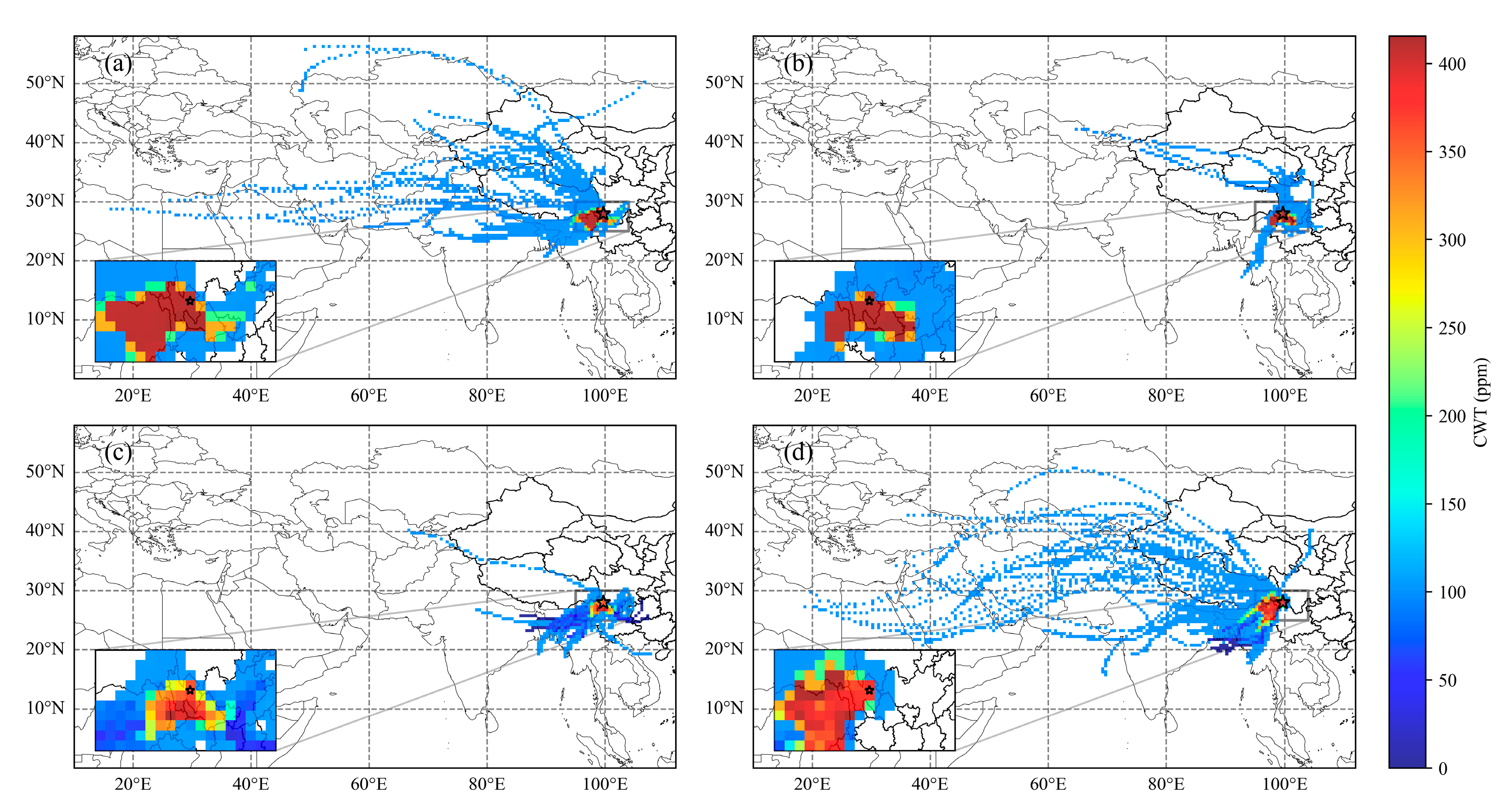

3.3. Trajectory Analysis

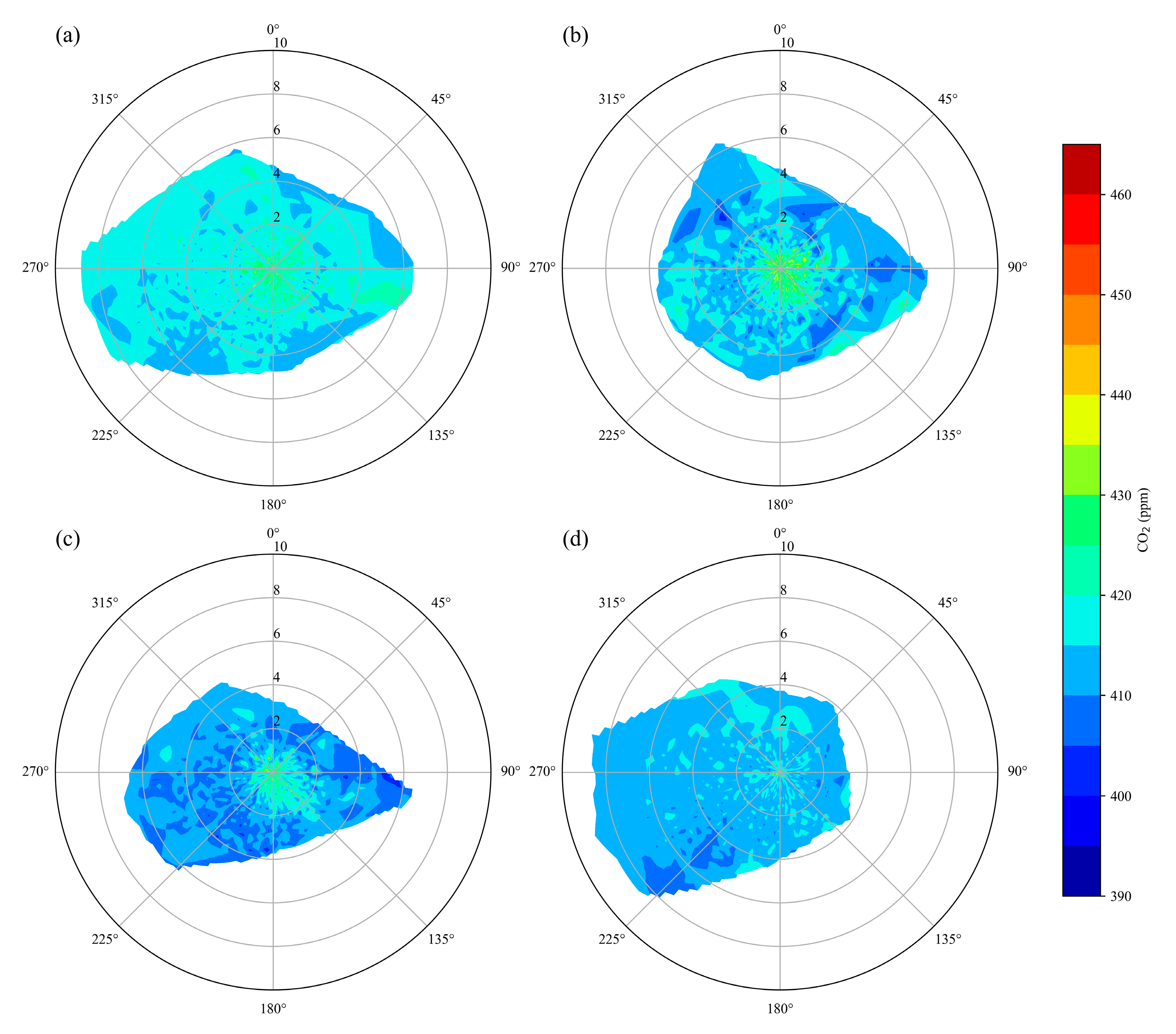

3.4. Wind Rose Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The REBS-derived background CO2 increased from ~409 ppm in 2019 to ~417 ppm in 2022, corresponding to an annual growth rate of 1.9 ± 0.1 ppm yr−1. This is slightly lower than both the 2010–2014 rate at the same site and the global mean growth rate during the same period (~2.4 ppm yr−1 for 2019–2022 [1]), consistent with the recent ENSO-modulated slowdown in global CO2 accumulation.

- (2)

- A distinct seasonal cycle, with spring maxima and late-summer minima, reflects the joint influence of biospheric activity and monsoonal circulation. Pronounced diurnal amplitudes in summer (up to 25 ppm) indicate strong daytime photosynthetic drawdown and nighttime accumulation under stable stratification.

- (3)

- Integrated HYSPLIT–PSCF–CWT analyses reveal that regional transport dominates high-CO2 episodes. Air masses primarily originate from the southern Indo-Myanmar and Sichuan-Yunnan regions. Relative to 2010–2016, potential source influence has shifted slightly toward the south and southeast of the station.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WMO. WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 21. Available online: https://wmo.int/publication-series/wmo-greenhouse-gas-bulletin-no-21 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.I. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contrib. Work. Group I Sixth Assess. Rep. Intergov. Panel Clim. Change 2021, 2, 2391. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 965–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.A. Revised estimates of the annual net flux of carbon to the atmosphere from changes in land use and land management 1850–2000. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2003, 55, 378–390. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, T.J.; Tans, P.P.; Waterman, L.S.; Thoning, K.W.; Kitzis, D.R.; Masarie, K.A.; Zhang, N. Evidence for interannual variability of the carbon cycle from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory Global Air Sampling Network. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994, 99, 22831–22855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, R.F. Recording Earth’s Vital Signs. Science 2008, 319, 1771–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briber, B.M.; Hutyra, L.R.; Dunn, A.L.; Raciti, S.M.; Munger, J.W. Variations in atmospheric CO2 mixing ratios across a Boston, MA urban to rural gradient. Land 2013, 2, 304–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, T.J.; Tans, P.P.; BBoden, T. Atmospheric Carbon Diooxide Mixing Ratios from the NOAA Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory Cooperative Flask Sampling Network, 1967–1993; Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1996.

- Keeling, C.D.; Bacastow, R.B.; Bainbridge, A.E.; Ekdahl, C.A., Jr.; Guenther, P.R.; Waterman, L.S.; Chin, J.F. Atmospheric carbon dioxide variations at Mauna Loa observatory, Hawaii. Tellus 1976, 28, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Conway, T.J.; White, J.W.; Mukai, H.; Zhang, X.; Wen, Y.; Li, J.; MacClune, K. Long-term record of atmospheric CO2 and stable isotopic ratios at Waliguan Observatory: Background features and possible drivers, 1991–2002. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2005, 19, GB3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, A.á.; Alden, C.á.; Miller, J.á.; Tans, P.á.; White, J. Increase in observed net carbon dioxide uptake by land and oceans during the past 50 years. Nature 2012, 488, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graven, H.; Keeling, R.; Piper, S.; Patra, P.; Stephens, B.; Wofsy, S.; Welp, L.; Sweeney, C.; Tans, P.; Kelley, J. Enhanced seasonal exchange of CO2 by northern ecosystems since 1960. Science 2013, 341, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, B.; Deng, X.; Zhang, F.; He, H.; Luan, T.; Li, F.; Liu, X. Background Characteristics of Atmospheric CO2 and the Potential Source Regions in the Pearl River Delta Region of China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 37, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Wen, M.; Zhang, F.; Yao, B.; Fang, S. The characteristics of atmospheric CO2 concentration variation of four national background stations in China. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2009, 52, 1857–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Tans, P.P.; Steinbacher, M.; Zhou, L.; Luan, T.; Li, Z. Observation of atmospheric CO2 and CO at Shangri-La station: Results from the only regional station located at southwestern China. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 2016, 68, 28506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Fang, S.; Liu, S.; Liang, M.; Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, F. Comparison of atmospheric CO2, CH4, and CO at two stations in the Tibetan Plateau of China. Earth Space Sci. 2020, 7, e2019EA001051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bowman, K.W.; Schimel, D.S.; Parazoo, N.C.; Jiang, Z.; Lee, M.; Bloom, A.A.; Wunch, D.; Frankenberg, C.; Sun, Y.; et al. Contrasting carbon cycle responses of the tropical continents to the 2015–2016 El Niño. Science 2017, 358, eaam5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Chao, W.C.; Liu, X. Enhanced climatic warming in the Tibetan Plateau due to doubling CO2: A model study. Clim. Dyn. 2003, 20, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Ting, M.; Ding, Y.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Yang, G. Distinctive South and East Asian monsoon circulation responses to global warming. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, Y.K.; Vellore, R.K.; Ravi Kumar, K.; van der Schoot, M.; Cho, C.-H. Influence of monsoons on atmospheric CO2 spatial variability and ground-based monitoring over India. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 490, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckstuhl, A.F.; Henne, S.; Reimann, S.; Steinbacher, M.; Vollmer, M.K.; O’Doherty, S.; Buchmann, B.; Hueglin, C. Robust extraction of baseline signal of atmospheric trace species using local regression. Atmos. Meas. Technol. 2012, 5, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.L.; Liu, X.M.; Liu, Y.J.; Hu, F. Characteristics of CO2 Concentration and Flux in the Beijing Urban Area. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 1785–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Yan, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Gao, X.a.; Ma, Z.; Liu, P.; Liang, M. Atmospheric CO2 Data Filtering Method and Characteristics of the Mole Fractions at Wutaishan Station in Shanxi of China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 2953–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yue, Y.; Jing, J.; Liang, M.; Sun, W.; Han, G.; Lou, M. Background Characteristics and Influence Analysis of Greenhouse Gases at Jinsha Atmospheric Background Station in China. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; Draxler, R.R.; Rolph, G.D.; Stunder, B.J.B.; Cohen, M.D.; Ngan, F. NOAA’s HYSPLIT Atmospheric Transport and Dispersion Modeling System. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashnikov, V.P.; Chaikovsky, A.P.; Kucsera, T.L.; Metelskaya, N.S. Estimated accuracy of three common trajectory statistical methods. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 5425–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Ghasemifard, H.; Yuan, Y.; Hachinger, S.; Zhao, X.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Bi, X.; Bai, Y.; Menzel, A.; Chen, J. Assessment of Urban CO2 Measurement and Source Attribution in Munich Based on TDLAS-WMS and Trajectory Analysis. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, B.; Deng, X.; Liu, X.; Li, T.; Guo, J.; Ma, Q. The climatology of ambient CO2 concentrations from long-term observation in the Pearl River Delta region of China: Roles of anthropogenic and biogenic processes. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 251, 118266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathakoti, M.; Kanchana, A.L.; Mahalakshmi, D.V.; Guha, T.; Raja, P.; Nalini, K.; Rajan, K.S.; Sesha Sai, M.V.R.; Dadhwal, V.K. Implications of Emission Sources and Biosphere Exchange on Temporal Variations of CO2 and δ13C Using Continuous Atmospheric Measurements at Shadnagar (India). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2022JD036472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metya, A.; Datye, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Tiwari, Y.K.; Sarma, D.; Bora, A.; Gogoi, N. Diurnal and seasonal variability of CO2 and CH4 concentration in a semi-urban environment of western India. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, R.A.; Jones, C.D.; Knight, J.R.; Keeling, R.F.; Kennedy, J.J. El Niño and a record CO2 rise. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 20. Available online: https://wmo.int/publication-series/wmo-greenhouse-gas-bulletin-no-20 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Shen, M.; Piao, S.; Chen, X.; An, S.; Fu, Y.H.; Wang, S.; Cong, N.; Janssens, I.A. Strong impacts of daily minimum temperature on the green-up date and summer greenness of the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 2016, 22, 3057–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, J.; Xiao, X. Green-up dates in the Tibetan Plateau have continuously advanced from 1982 to 2011. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4309–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Gui, K.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Sheng, Z.; Sun, T.; Zhang, X.; Che, H. Impact of Biomass Burning in South and Southeast Asia on Background Aerosol in Southwest China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2019, 19, 1188–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Hu, M.; Du, Z.; Shang, D.; Gong, Z.; Qin, Y.; Fang, J.; Gu, F.; Li, M.; Peng, J.; et al. Influence of biomass burning from South Asia at a high-altitude mountain receptor site in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 6853–6864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, Y.; Zhou, R.; Duan, X.; Peng, X.; Song, X.; He, W.; Li, X.; Zhima, C. Characteristics of Atmospheric CO2 at Shangri-La Regional Atmospheric Background Station in Southwestern China: Insights from Recent Observations (2019–2022). Atmosphere 2026, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010003

Yin Y, Zhou R, Duan X, Peng X, Song X, He W, Li X, Zhima C. Characteristics of Atmospheric CO2 at Shangri-La Regional Atmospheric Background Station in Southwestern China: Insights from Recent Observations (2019–2022). Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Yuemiao, Ronglian Zhou, Xuqin Duan, Xiaoqing Peng, Xiaorui Song, Wei He, Xiaoli Li, and Ciyong Zhima. 2026. "Characteristics of Atmospheric CO2 at Shangri-La Regional Atmospheric Background Station in Southwestern China: Insights from Recent Observations (2019–2022)" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010003

APA StyleYin, Y., Zhou, R., Duan, X., Peng, X., Song, X., He, W., Li, X., & Zhima, C. (2026). Characteristics of Atmospheric CO2 at Shangri-La Regional Atmospheric Background Station in Southwestern China: Insights from Recent Observations (2019–2022). Atmosphere, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010003