Automating Air Pollution Map Analysis with Multi-Modal AI and Visual Context Engineering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Maps

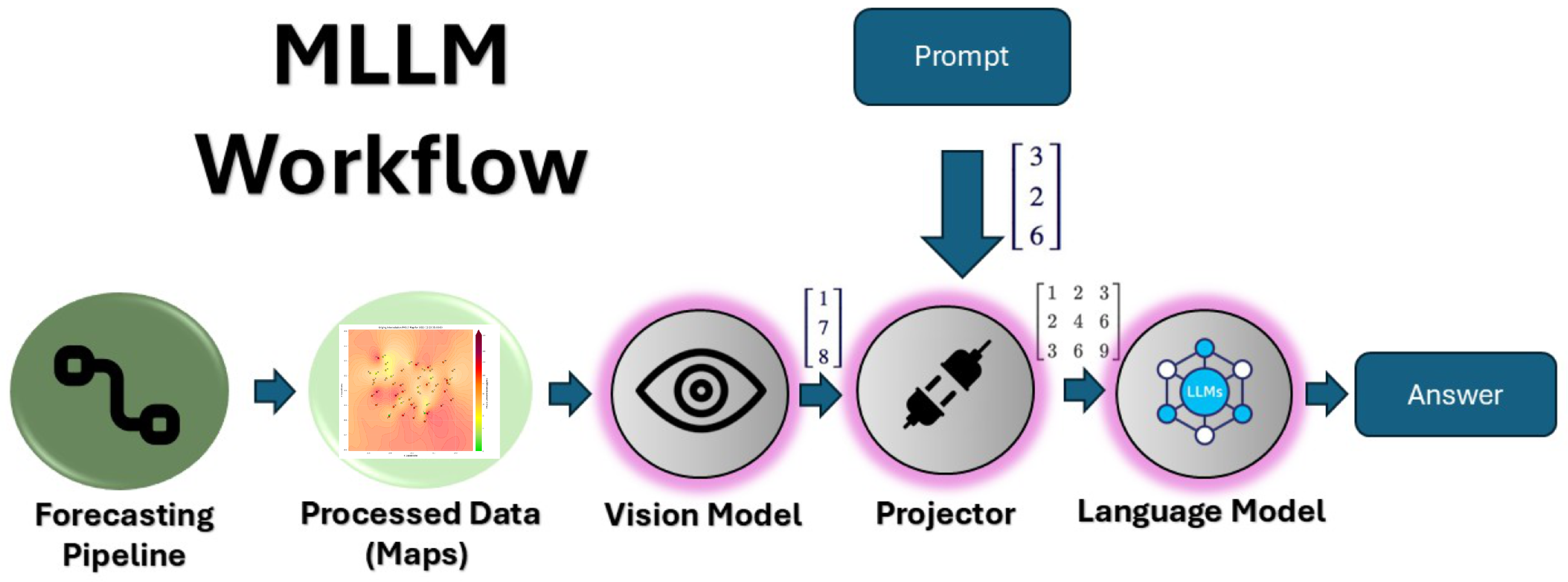

2.2. Multimodal Large Language Models

2.3. Visual Context Optimization for MLLM Interpretation

2.4. Evaluation

2.4.1. Manual Subjective Evaluation

- Temporal reasoning—recognizing and describing changes over time between consecutive visualizations (e.g., sequences of PM2.5 maps);

- Identification of spatial extremes—detecting and describing hot spots (high-concentration regions) and cold spots (low-concentration regions);

- Recognition of spatial gradients—interpreting gradual attenuation or intensification of PM2.5 concentrations and identifying the general direction of dispersion;

- Tracking of PM2.5 cluster displacements—detecting movement or shifting of pollution concentration clusters between time steps, indicating dynamic atmospheric transport or meteorological influence.

2.4.2. Automated Evaluation with G-Eval

3. Results

- (i)

- Map I—a correctly prepared map after context engineering, using a customized color scale inspired by the AQI scheme (see Section 2.3, Visual Context Optimization for MLLM Interpretation);

- (ii)

- Map II—a correctly prepared map with an additional overlaid shapefile;

- (iii)

- Map III—a raw, unprocessed map rendered with a variable color scale (Vardis), corresponding to near-default plotting parameters;

- (iv)

- Map IV—a raw Vardis map with an overlaid shapefile.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dominici, F.; Peng, R.D.; Bell, M.L.; Pham, L.; McDermott, A.; Zeger, S.L.; Samet, J.M. Fine Particulate Air Pollution and Hospital Admission for Cardiovascular and Respiratory Diseases. JAMA 2006, 295, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamkiewicz, G.; Liddie, J.; Gaffin, J.M. The Respiratory Risks of Ambient/Outdoor Air Pollution. Clin. Chest Med. 2020, 41, 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Chen, D.; Jiao, K.; Wang, X.; Suo, J.; Yang, H.; Liao, J.; Ma, L. Effect of Ambient Fine Particulates (PM2.5) on Hospital Admissions for Respiratory and Cardiovascular Diseases in Wuhan, China. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danesh Yazdi, M.; Wang, Y.; Di, Q.; Wei, Y.; Requia, W.J.; Shi, L.; Sabath, M.B.; Dominici, F.; Coull, B.A.; Evans, J.S.; et al. Long-Term Association of Air Pollution and Hospital Admissions Among Medicare Participants Using a Doubly Robust Additive Model. Circulation 2021, 143, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zeng, Y.; Lau, A.K.H.; Guo, C.; Wei, X.; Lin, C.; Huang, B.; Lao, X.Q. Chronic Exposure to Ambient PM2.5/NO2 and Respiratory Health in School Children: A Prospective Cohort Study in Hong Kong. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 114558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Xue, Y.; Thandra, S.; Qi, Q.; Hopke, P.K.; Thurston, S.W.; Croft, D.P.; Utell, M.J.; Rich, D.Q. PM2.5 and Its Components and Respiratory Disease Healthcare Encounters—Unanticipated Increased Exposure–Response Relationships in Recent Years after Environmental Policies. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 360, 124585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Mutlu, G.M. Particulate Matter Air Pollution: Effects on the Respiratory System. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e194312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R. The Cardiovascular Effects of Air Pollution: Prevention and Reversal by Pharmacological Agents. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 232, 107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bont, J.; Jaganathan, S.; Dahlquist, M.; Persson, r.; Stafoggia, M.; Ljungman, P. Ambient Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Diseases: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 291, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeeff, S.E.; Deosaransingh, K.; Van Den Eeden, S.; Schwartz, J.; Liao, N.S.; Sidney, S. Association of Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution with Cardiovascular Events in California. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e230561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Gruszecka-Kosowska, A.; Oikonomou, E. Burden of Cardiovascular Disease Attributed to Air Pollution: A Systematic Review. Glob. Health 2024, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, Q.; Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Zanobetti, A.; Choirat, C.; Schwartz, J.D.; Dominici, F. Association of Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution with Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA 2017, 318, 2446–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Hoek, G. Long-Term Exposure to PM and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelieveld, J.; Pozzer, A.; Pöschl, U.; Fnais, M.; Haines, A.; Münzel, T. Loss of Life Expectancy from Air Pollution Compared to Other Risk Factors: A Worldwide Perspective. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1910–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.F.; Xu, Y.H.; Shi, M.H.; Lian, Y.X. The Impact of PM2.5 on the Human Respiratory System. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E69–E74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentschler, J.; Leonova, N. Global Air Pollution Exposure and Poverty. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajat, A.; Hsia, C.; O’Neill, M.S. Socioeconomic Disparities and Air Pollution Exposure: A Global Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strosnider, H.; Kennedy, C.; Monti, M.; Yip, F. Rural and Urban Differences in Air Quality, 2008–2012, and Community Drinking Water Quality, 2010–2015—United States. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2017, 66, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Su, T.; Chen, T.; Wei, J.; Cribb, M. The Urban–Rural Heterogeneity of Air Pollution in 35 Metropolitan Regions across China. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Air Quality Guidelines: Global Update 2005—Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Malings, C.; Tanzer, R.; Hauryliuk, A.; Saha, P.K.; Robinson, A.L.; Presto, A.A.; Subramanian, R. Fine Particle Mass Monitoring with Low-Cost Sensors: Corrections and Long-Term Performance Evaluation. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1272–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.L.; Mebust, A.K.; Maghran, L.A.; McGown, M.R.; Stewart, K.E.; Vallano, D.M.; Elleman, R.A.; Baker, K.R. Field Evaluation of Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors for Measuring Wildfire Smoke. Sensors 2020, 20, 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy Zamora, M.; Rice, J.; Koehler, K. One Year Evaluation of Three Low-Cost PM2.5 Monitors. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 235, 117615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feenstra, B.; Papapostolou, V.; Hasheminassab, S.; Zhang, H.; Der Boghossian, B.; Cocker, D.; Polidori, A. Performance Evaluation of Twelve Low-Cost PM2.5 Sensors at an Ambient Air Monitoring Site. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 216, 116946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Ma, C.; Ran, M. AirGPT: Pioneering the Convergence of Conversational AI with Atmospheric Science. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Lu, M.; Chen, G.; Fu, B.; Xu, Z.; Xin, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Cao, J. Unraveling the Complex Impact of Climate Change on Air Quality in the World. NPJ Clean Air 2025, 1, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Lu, D.; Li, L.; Chen, N.; He, H.; Du, J.; Xu, L.; Li, J. Instructor–Worker Large Language Model System for Policy Recommendation: A Case Study on Air Quality Analysis of the January 2025 Los Angeles Wildfires. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 133, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esager, M.W.M.; Ünlü, K.D. Forecasting Air Quality in Tripoli: An Evaluation of Deep Learning Models for Hourly PM2.5 Surface Mass Concentrations. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cui, B.; Liu, Z. Air Quality Class Prediction Using Machine Learning Methods Based on Monitoring Data and Secondary Modeling. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım Özüpak, F.; Alpsalaz, F.; Aslan, E. Air Quality Forecasting Using Machine Learning: Comparative Analysis and Ensemble Strategies for Enhanced Prediction. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoomi, A.; Sarkhosh, M.; Ziaei, S. PM2.5 Concentration Prediction Using Machine Learning Algorithms: An Approach to Virtual Monitoring Stations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utku, A.; Can, U.; Alpsülün, M.; Balıkçı, H.C.; Amoozegar, A.; Pilatin, A.; Barut, A. Advancing Air Quality Monitoring: Deep Learning-Based CNN–RNN Hybrid Model for PM2.5 Forecasting. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Danek, T.; Zajac, J. On Including Near-surface Zone Anisotropy for Static Corrections Computation—Polish Carpathians 3D Seismic Processing Case Study. Geosciences 2020, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Cogiel, S.; Danek, T.; Weglinska, E. Machine Learning Techniques for Spatio-Temporal Air Pollution Prediction to Drive Sustainable Urban Development in the Era of Energy and Data Transformation. Energies 2024, 17, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Cogiel, S.; Danek, T. Spatio-Temporal PM2.5 Forecasting Using Machine Learning and Low-Cost Sensors: An Urban Perspective. Eng. Proc. 2025, 101, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danek, T.; Zaręba, M. The Use of Public Data from Low-Cost Sensors for the Geospatial Analysis of Air Pollution from Solid Fuel Heating during the COVID-19 Pandemic Spring Period in Krakow, Poland. Sensors 2021, 21, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, E.; Lupa, M.; Zaręba, M.; Węglińska, E.; Danek, T.; Mishra, A.K. Emergency Medical Interventions in Areas with High Air Pollution: A Case Study from Małopolska Voivodeship, Poland. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M.; Danek, T. A novel methodology for Explainable Artificial Intelligence integrated with geostatistics for air pollution control and environmental management. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 92, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, M. Assessing the Role of Energy Mix in Long-Term Air Pollution Trends: Initial Evidence from Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Pan, L. Policy Effect on Clean Coal-Fired Power Development in China. Energies 2022, 15, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.K. Elevated Black Carbon Concentrations and Atmospheric Pollution around Singrauli Coal-Fired Thermal Power Plants (India) Using Ground and Satellite Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Copernicus Land Monitoring Service 2022—Digital Terrain Model (EU-DEM). 2022. European Union, Copernicus Land Monitoring Service, European Environment Agency (EEA). Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/imagery-in-situ/eu-dem (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. OpenStreetMap. 2025. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Matheron, G. Principles of Geostatistics. Econ. Geol. 1963, 58, 1246–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressie, N.A.C. Statistics for Spatial Data, revised ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Brown, E.; Wu, P.; Woo, S.; Middepogu, M.; Akula, S.C.; Yang, J.; Yang, S.; Iyer, A.; Pan, X.; et al. Cambrian-1: A Fully Open, Vision-Centric Exploration of Multimodal LLMs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Pan, Z.; Liu, W.; Xie, Z.; Yu, X.; Ruan, C. Janus-Pro: Unified Multimodal Understanding and Generation with Data and Model Scaling. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.17811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Iter, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, R.; Zhu, C. G-Eval: NLG Evaluation using GPT-4 with Better Human Alignment. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.16634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. GPT-4o System Card: An Omni-modal Foundation Model for Text, Audio, Image, and Video. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21276. [Google Scholar]

- DeepMind, G. Gemini 2.X: Pushing the Frontier with Advanced Reasoning—Model Card and Technical Report for Gemini 2.5 Pro & Flash. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.06261. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Map Variant | Map Type (Color Scale) | Shapefile Overlay | G-Eval Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Map I | Context-engineered (AQI) | No | 0.381 |

| Map II | Context-engineered (AQI) | Yes | 0.253 |

| Map III | Raw map (Viridis) | No | 0.288 |

| Map IV | Raw map (Viridis) | Yes | 0.274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cogiel, S.; Zareba, M.; Danek, T.; Arnaut, F. Automating Air Pollution Map Analysis with Multi-Modal AI and Visual Context Engineering. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010002

Cogiel S, Zareba M, Danek T, Arnaut F. Automating Air Pollution Map Analysis with Multi-Modal AI and Visual Context Engineering. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleCogiel, Szymon, Mateusz Zareba, Tomasz Danek, and Filip Arnaut. 2026. "Automating Air Pollution Map Analysis with Multi-Modal AI and Visual Context Engineering" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010002

APA StyleCogiel, S., Zareba, M., Danek, T., & Arnaut, F. (2026). Automating Air Pollution Map Analysis with Multi-Modal AI and Visual Context Engineering. Atmosphere, 17(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010002