Transition from Slow Drought to Flash Drought Under Climate Change in Northern Xinjiang, Northwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

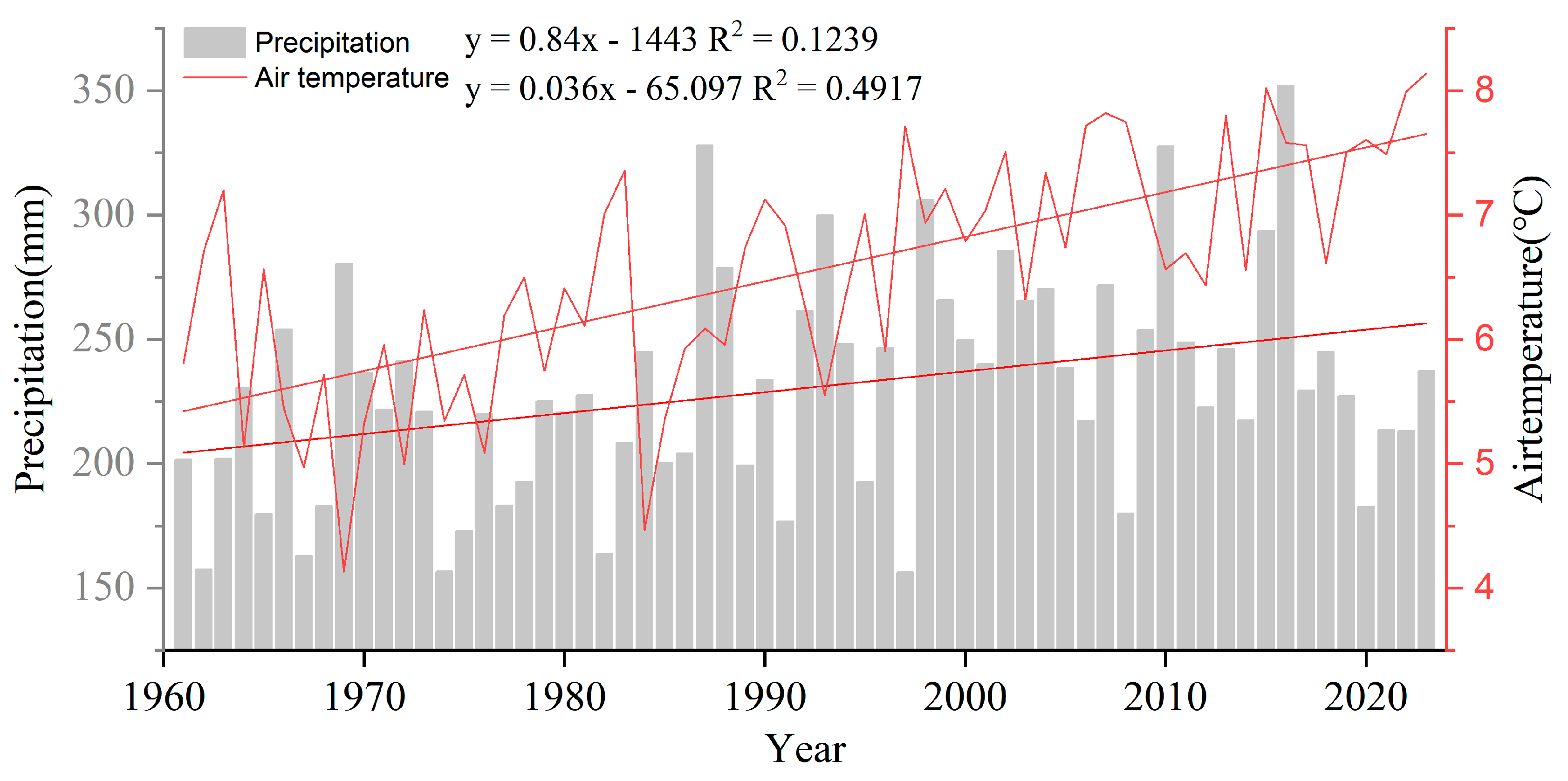

2.2. Data

2.2.1. Meteorological Data

2.2.2. Atmospheric Circulation Index Data

3. Method

3.1. Rules for Fast-Onset Drought (FOD) Identification

- (1)

- The SPEI drops from ≥0 to <−1 within four consecutive pentads, signaling a rapid shift to at least moderate drought;

- (2)

- The dry spell persists for ≥3 pentads, ensuring agronomic impact;

- (3)

- The SPEI recovers to ≥−1, marking event termination.

3.2. Mann–Kendall Abrupt Change Detection

3.3. Random Forest Model

4. Results

4.1. The Spatio-Temporal Variation Characteristics of Drought Intensity

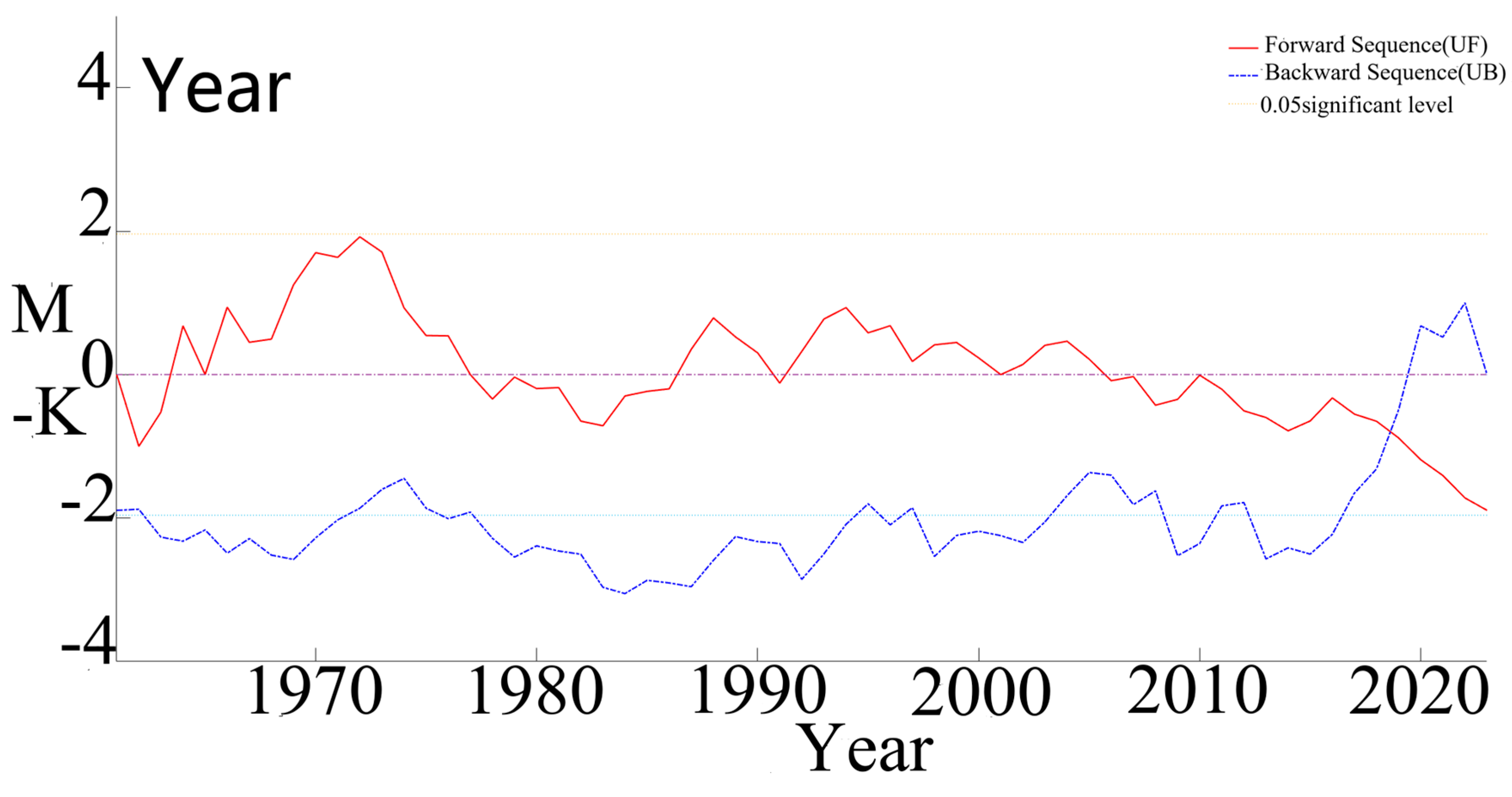

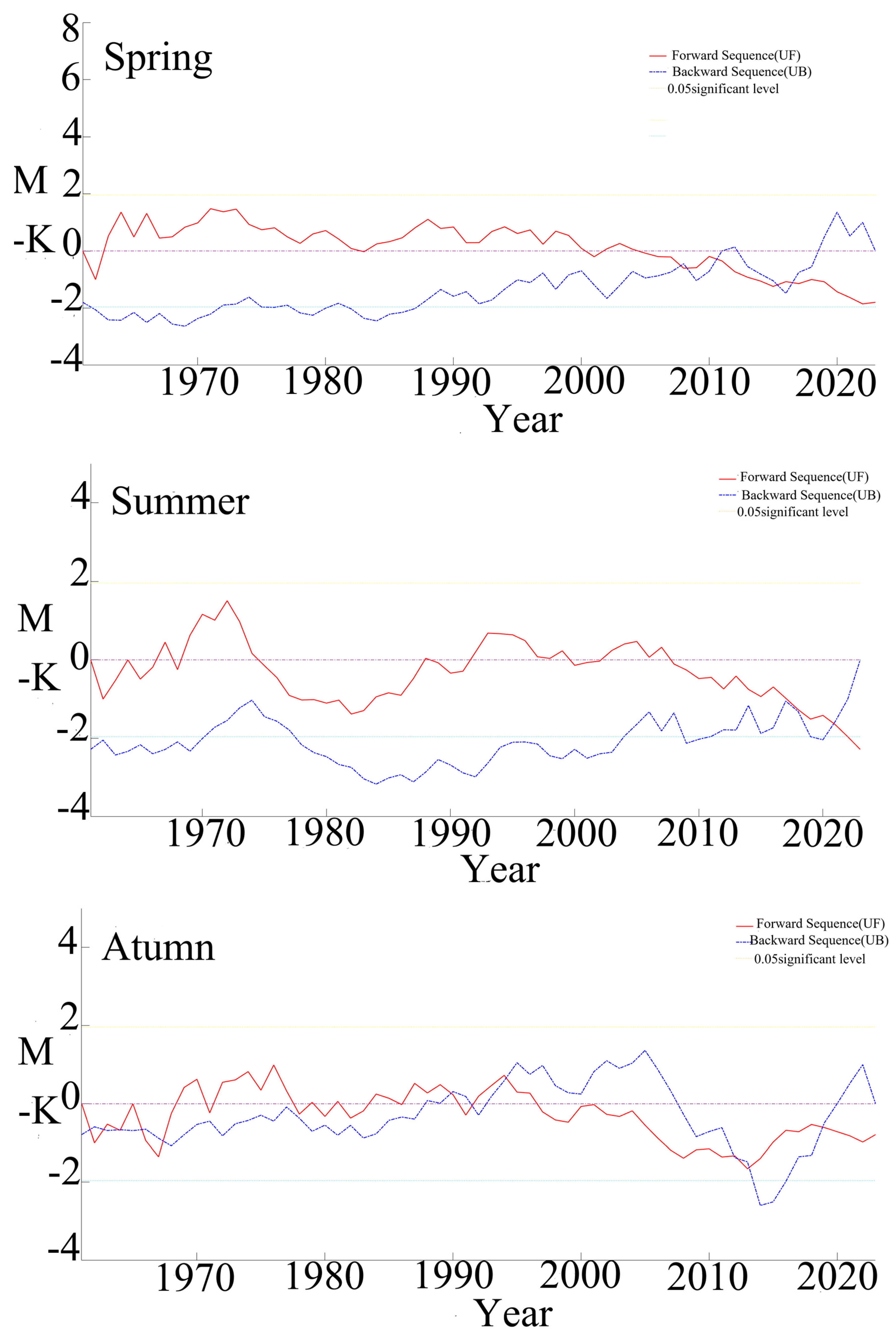

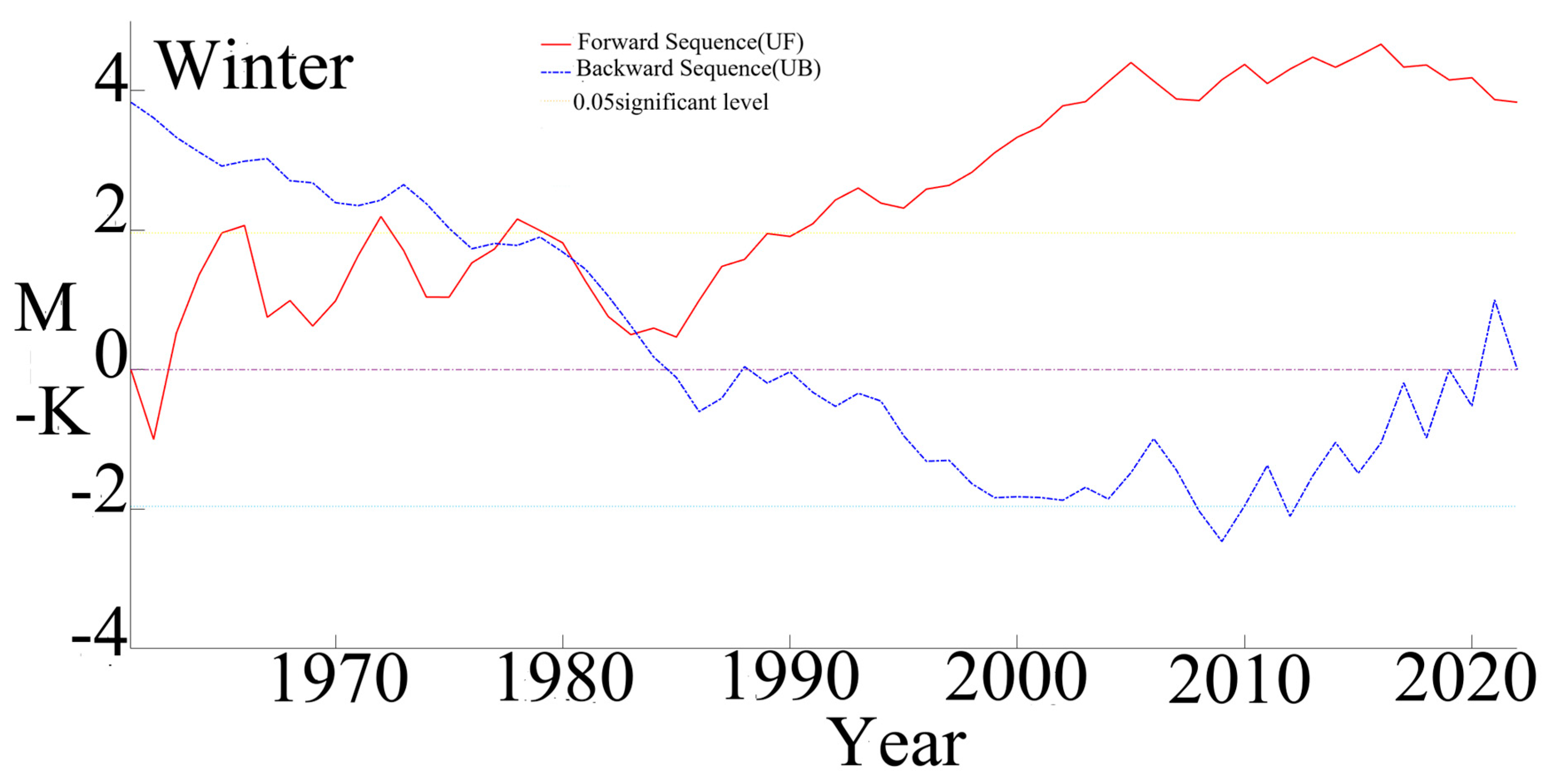

4.2. SPEI Abrupt Change Analysis

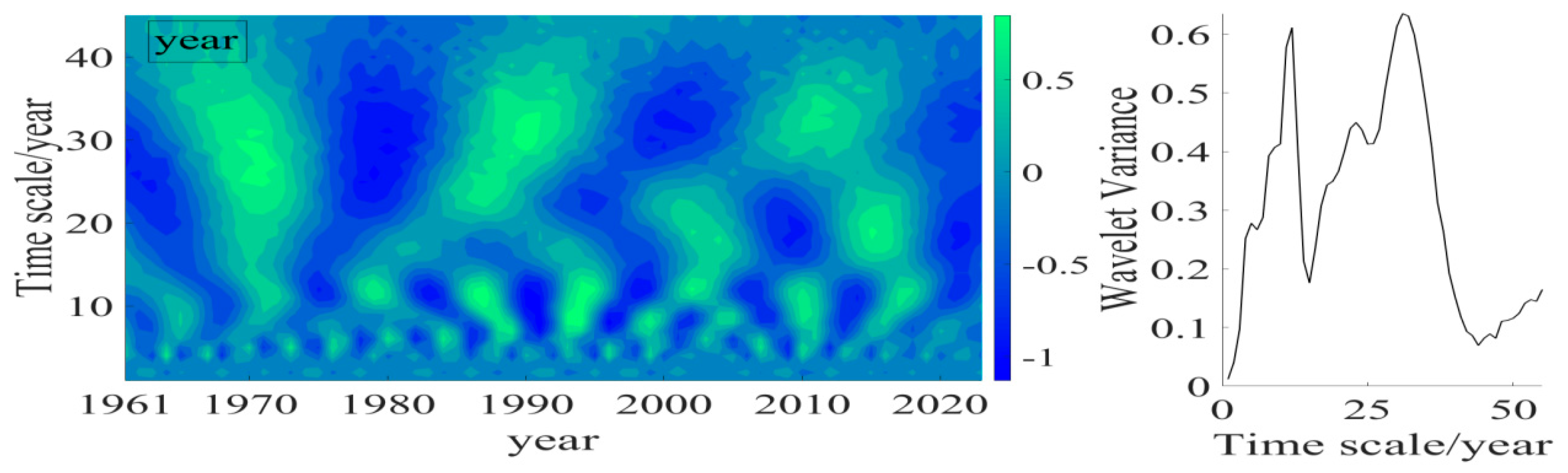

4.3. Morlet Wavelet Analysis of SPEI

4.4. Identification and Feature Analysis of Flash Drought

4.5. Influencing Factors of Flash Drought

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahto, S.S.; Mishra, V. Dominance of summer monsoon flash droughts in India. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Zaitchik, B.F.; Badr, H.S.; Christian, J.I.; Tadesse, T.; Otkin, J.A.; Anderson, M.C. Flash drought onset over the contiguous United States: Sensitivity of inventories and trends to quantitative definitions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, M.; LeComte, D.; Hayes, M.; Heim, R.; Gleason, K.; Angel, J.; Rippey, B.; Tinker, R.; Palecki, M.; Stephens, S.; et al. The drought monitor. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2002, 83, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisonbee, J.; Woloszyn, M.; Skumanich, M. Making sense of flash drought: Definitions, indicators, and where we go from here. J. Appl. Serv. Climatol. 2021, 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xia, J.; She, D.X.; Li, L.C.; Song, Z.H.; Hong, S. A new framework for the identification of flash drought: Multivariable and probabilistic statistic perspectives. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 5862–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.Z.; Wang, L.X.; McCabe, M.F. Multi-sensor remote sensing for drought characterization: Current status, opportunities and a roadmap for the future. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.L.; Yuan, X. Critical role of soil moisture memory in predicting the 2012 Central United States flash drought. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 615969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Aadhar, S.; Mahto, S.S. Anthropogenic warming and intraseasonal summer monsoon variability amplify the risk of future flash droughts in India. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.H.; Wang, M.L.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S.W.; Zhang, L.J. Spatiotemporal characteristics and meteorological driving factors of flash droughts in the yellow river basin, china. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergrass, A.G.; Meehl, G.A.; Pulwarty, R.; Hobbins, M.; Hoell, A.; Aghakouchak, A.; Bonfils, C.J.W.; Gallant, A.J.E.; Hoerling, M.; Woodhouse, C.A.; et al. Flash droughts present a new challenge for subseasonal-to-seasonal prediction. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, P.; Wu, P.P.; Sheffield, J.; Otkin, J.A. A global transition to flash droughts under climate change. Science 2023, 380, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, J.I.; Basara, J.B.; Hunt, E.D.; Otkin, J.A.; Furtado, J.C.; Mishra, V.; Xiao, X.M.; Randall, R.M. Global distribution, trends, and drivers of flash drought occurrence. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.M.; Wang, S.; Ancell, B.C.; Yang, Z.L. Accelerating flash droughts induced by the joint influence of soil moisture depletion and atmospheric aridity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeparvathy, V.; Srinivas, V.V. Meteorological flash droughts risk projections based on CMIP6 climate change scenarios. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.Q.; Dong, Z.J.; Liu, K.Y.; Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, Y.K.; Zhong, D.Y. Analysis of spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of flash droughts in jialing river basin. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 2024, 44, 23–30+58. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, T.W.; Labosier, C.F. Meteorological conditions associated with the onset of flash drought in the Eastern United States. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 247, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, L.Y.; Wu, P.L.; Ji, P.; Sheffield, J.; Zhang, M. Anthropogenic shift towards higher risk of flash drought over China. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, L.L.; Otkin, J.; Hunt, E.D.; Yang, X.L.; Yuan, F.; Jiang, S.H. Two different methods for flash drought identification: Comparison of their strengths and limitations. J. Hydrometeorol. 2020, 21, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Xu, M.Y.; Dong, J.L.; Yao, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.B.; Javed, T.; Zhuo, L.; Yu, Q. Response and resilience of farmland ecosystems to flash drought in China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 176, 113643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Precipitation deficit flash droughts over the United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 2016, 17, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.G.; Gottschalck, J.; Hartman, A.; Miskus, D.; Tinker, R.; Artusa, A. Flash drought characteristics based on U.S. drought monitor. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, J.I.; Basara, J.B.; Otkin, J.A.; Hunt, E.D.; Wakefield, R.A.; Flanagan, P.X.; Xiao, X.M. A methodology for flash drought identification: Application of flash drought frequency across the United States. J. Hydrometeorol. 2019, 20, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS). Flash Drought: Current Understanding and Future Priorities; NIDIS: Gisborne, VIC, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X. Flash droughts in the Pearl River Basin, China: Observed characteristics and future changes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 136074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basara, J.B.; Christian, J.I.; Wakefield, R.A.; Otkin, J.A.; Hunt, E.H.; Brown, D.P. The evolution, propagation, and spread of flash drought in the Central United States during 2012. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 084025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, J.I.; Basara, J.B.; Hunt, E.D.; Otkin, J.A.; Xiao, X. Flash drought development and cascading impacts associated with the 2010 Russian heatwave. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Wheeler, M.C.; A Otkin, J.; Cowan, T.; Frost, A.J.; Stone, R.C. Using the evaporative stress index to monitor flash drought in Australia. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 064016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.H.; Wang, H.J.; Sun, G.L.; Xu, C.C. Formation and risk analysis of meteorological disasters in Xinjiang. Arid Reg. Geogr. 2016, 39, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.W.; Xue, L.Q.; Wang, X.P.; Bai, Y.G.; Luo, J.Z. Characteristics and Causes of Drought Disasters in Tahe Basin. In Drought Warning and Disaster Effect Risk Assessment in the Tahe River Basin, 1st ed.; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, A.J.; Yang, Y.; Dai, X.A. Spatial clustering study of flood and drought disasters at the county scale in Xinjiang in the past 30 years. J. Nat. Disasters 2017, 26, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.Q.; Hu, R.J. Climate change and the expansion of flood and drought disasters in Xinjiang in the past 50 years. Desert China 2004, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.H. Research on Drought Monitoring and Analysis in Northern Xinjiang. Ph.D. Thesis, Xinjiang University, Urumqi, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.G.; Rouzi, M.S.; Lei, X.Y.; Zhang, J.H. Characteristics and influencing factors of drought disasters in Xinjiang. People’s Yellow River 2012, 34, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.F. The Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of Meteorological Drought in Northern Xinjiang over the Past 52 Years. Ph.D. Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Yue, P. Analysis of Dry and Wet Evolution and Persistent Characteristics in Northwest China over the Past Half Century. Arid Reg. Geogr. 2012, 35, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.P.; Nan, Z.T.; Cheng, G.D. GRACE gravity satellite monitoring of drought characteristics in Xinjiang. Resour. Environ. Arid Areas 2015, 29, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.W.; Song, J.; Wang, G.; Wu, X.Y.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal characteristic and forecast of drought in northern Xinjiang, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wu, S.X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M. Research on Xinjiang Oasis Based on Multiple Spatiotemporal Data. Arid Reg. Geogr. 2014, 37, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.R.; Zheng, J.H.; Lu, B.B.; Wang, R.J.; Han, W.Q.; Harris, P. Spatiotemporal drought forecasting in Xinjiang’s irrigated agriculture: Model comparison and multi-source data integration. J. Hydrol. 2025, 660, 133483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, Q.; Han, X.Y.; Liu, Y.L. Spatial and temporal differences in extreme precipitation events in Xinjiang from 1961 to 2009. Desert China 2014, 34, 550–557. [Google Scholar]

- Abulizi, A.; Shang, S.C. Analysis of River Runoff Characteristics in Xinjiang. Drought Environ. Monit. 2003, 2, 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.C.; Li, J.S.; Zhao, J.; Gao, S.T.; Chen, Y.P. Climate variations in northern Xinjiang of China over the past 50 years under global warming. Quatern. Int. 2015, 358, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Xu, J.H.; Chen, Z.S.; Li, W.H.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhao, B.F.; Wang, Z.J. The regional features of temperature variation trends over Xinjiang in China by the ensemble empirical mode decomposition method. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 35, 3229–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.B.; Choy, S.L.; Zaminpardaz, S.; Wang, X.M.; Liang, H.; Zhang, K.F. Flash drought monitoring using diurnal-provided evaporative demand drought index. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 633, 130961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Ma, Z.G.; Pan, M.; Shi, C.X. Microwave remote sensing of short-term droughts during crop growing seasons. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 4394–4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H. Identification and Evolution Characteristics Analysis of Sudden Drought in Northern Xinjiang Based on SPEI Index. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X.; Li, B.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhao, X.W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.L. Analysis of Precipitation and Runoff Changes in the North Canal Basin Based on Mann Kendall Test. Beijing Water 2022, 1, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.S.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.F.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Y. Combination of fractional order derivative and memory-based learning algorithm to improve the estimation accuracy of soil organic matter by visible and near-infrared spectroscopy. Catena 2019, 174, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.Q.; Chen, Y.N.; Zhao, Y.; Mao, W.Y.; Xu, X.B.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q. Response of vegetation NDVI to climatic extremes in the arid region of Central Asia: A case study in Xinjiang, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 131, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.F.; Chen, Y.N.; Shi, X. Why does the temperature rise faster in the arid region of northwest China? J. Geophys. Res. 2012, 117, D16115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.P.; Sun, J.Q. Changes in drought characteristics over China using the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 2015, 28, 5430–5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, C.F. Impacts of the superimposed climate trends on droughts over 1960–2013 in Xinjiang, China. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 129, 977–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.Q.; Hu, R.J. Climate change and flood & drought disasters in Xinjiang during recent 50 years. J. Desert Res. 2004, 24, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

| Time Scale | First Main Cycle (Year) | Number of Oscillations (First Main Cycle) | Second Main Cycle (Years) | Number of Oscillations (Second Main Cycle) | Third Main Cycle (Years) | Number of Oscillations (Third Main Cycle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual | 30 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 19 |

| Summer | 30 | 4 | 18 | 6 | 4 | 18 |

| Autumn | 10 | 9 | 20 | 5 | 40 | 2 |

| Winter | 22 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 45 | 3 |

| Spring | 10 | 9 | 27 | 4 | 50 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abbas, A.; Bake, B.; Sattar, M. Transition from Slow Drought to Flash Drought Under Climate Change in Northern Xinjiang, Northwest China. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010010

Abbas A, Bake B, Sattar M. Transition from Slow Drought to Flash Drought Under Climate Change in Northern Xinjiang, Northwest China. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Alim, Batur Bake, and Mutallip Sattar. 2026. "Transition from Slow Drought to Flash Drought Under Climate Change in Northern Xinjiang, Northwest China" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010010

APA StyleAbbas, A., Bake, B., & Sattar, M. (2026). Transition from Slow Drought to Flash Drought Under Climate Change in Northern Xinjiang, Northwest China. Atmosphere, 17(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010010