Simplifying Air Quality Forecasting: Logistic Regression for Predicting Particulate Matter in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

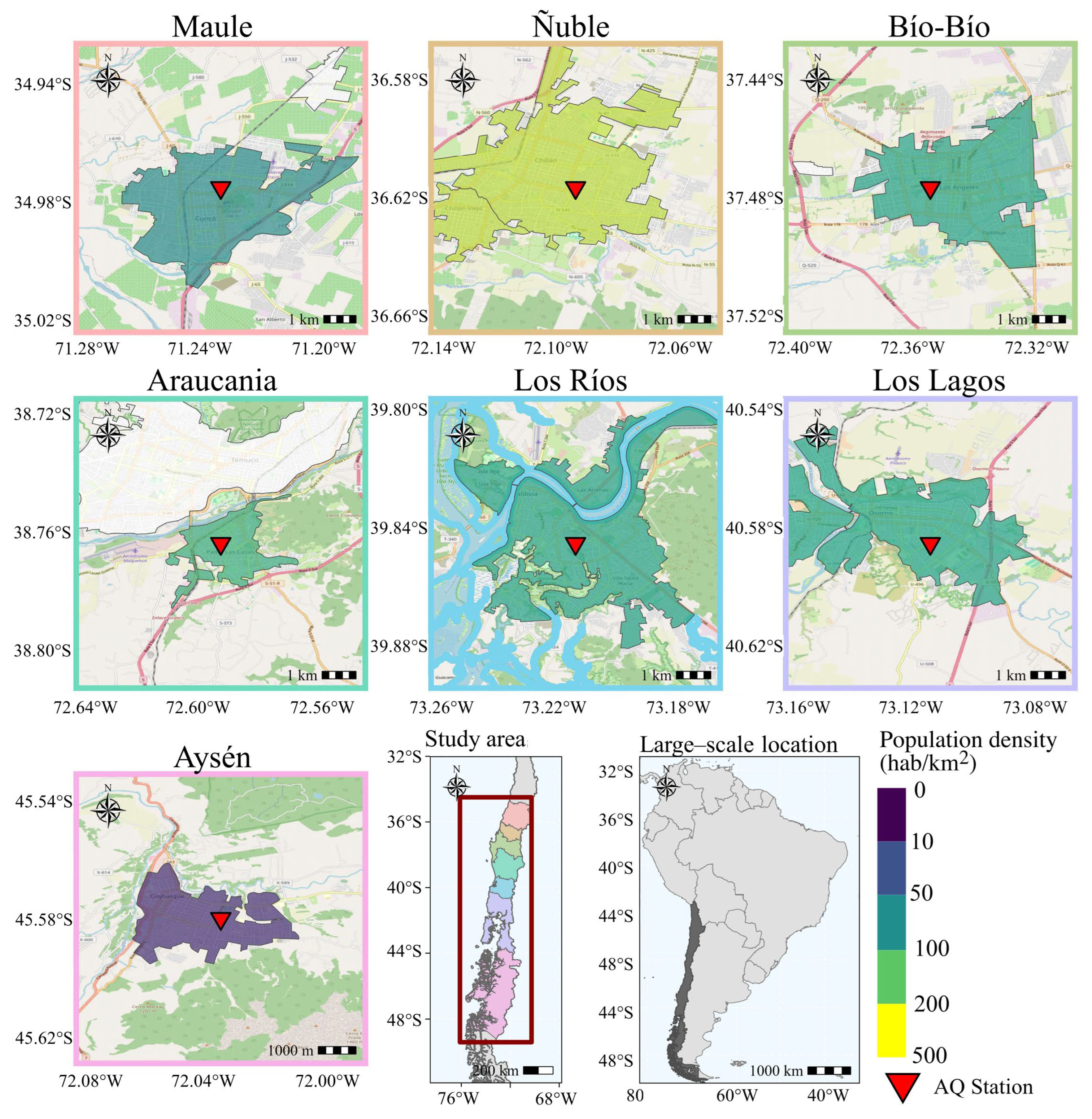

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Database

2.3. Threshold Forecast Design

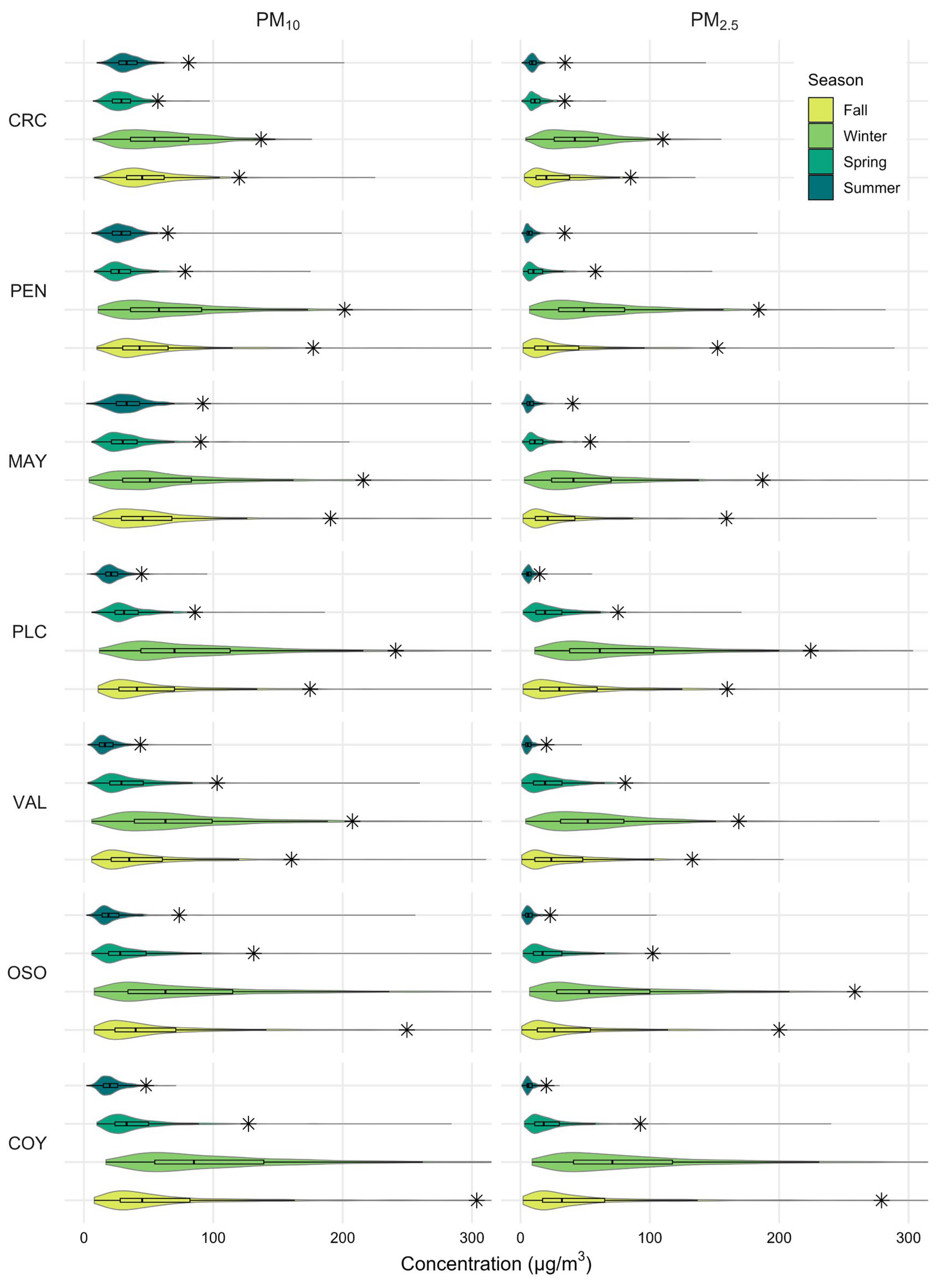

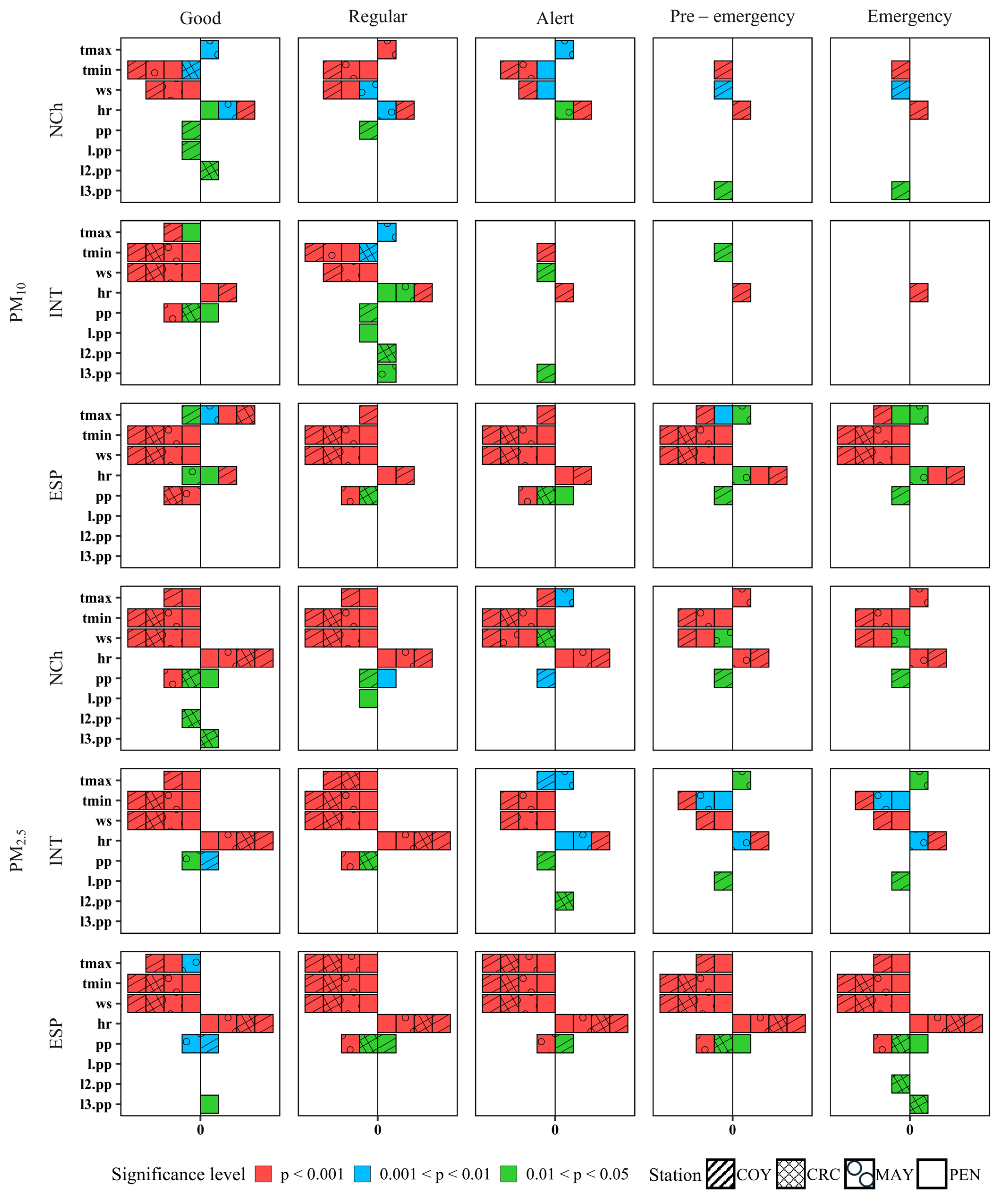

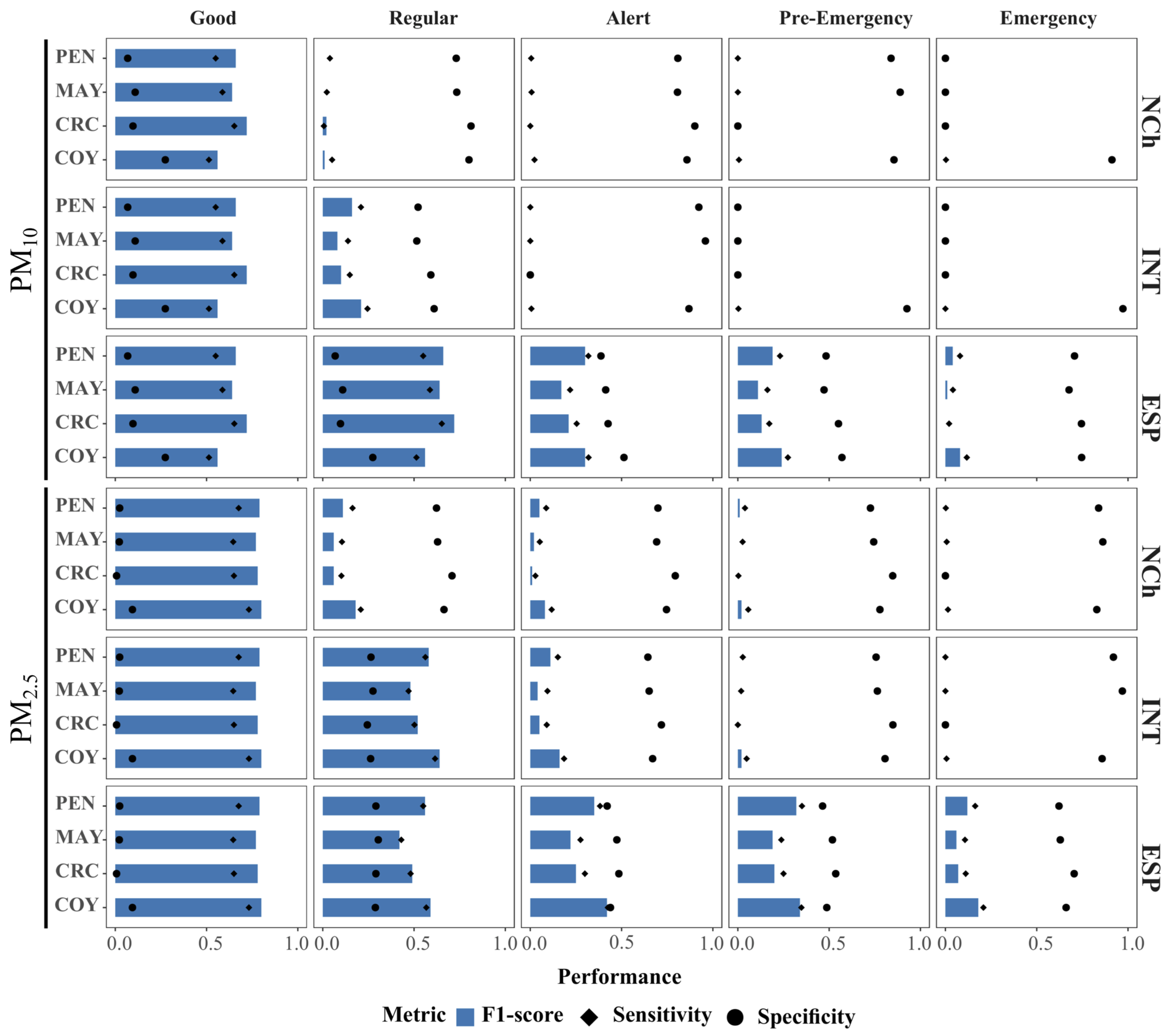

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AQI | Air Quality Index |

| COY | Coyhaique monitoring station |

| CRC | Curicó monitoring station |

| CR2 | Climate Science and Resilience Center (Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia, Chile) |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| ESP | European Air Quality Standard |

| HR | Relative Humidity |

| INT | International Air Quality Index (U.S. EPA) |

| Logit | Logistic Regression Model |

| l1.pp | Precipitation with a one-day lag |

| l2.pp | Precipitation with a two-day lag |

| l3.pp | Precipitation with a three-day lag |

| MAY | 21 de Mayo monitoring station |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NCh | Chilean Primary Air Quality Standard |

| OP | Oxidative Potential |

| OSO | Osorno monitoring station |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| PEN | Pemuco monitoring station |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm |

| PM10 | Particulate Matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm |

| PP | Precipitation |

| SINCA | National Air Quality Information System of Chile (Sistema de Información Nacional de Calidad del Aire) |

| ws | Wind speed |

References

- Matamoros, J.R.; Ramírez, M.A.M.; Zamorano, S.M.B. La relación entre la contaminación del aire por material particulado y la salud de la vegetación urbana. Rev. SPINOR 2025, 60, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira, J.; Domingo, J.L.; Schuhmacher, M. Calidad Del Aire, Impactos En La Salud y Carga de Enfermedad Por Contaminación Atmosférica (PM10, PM2.5, NO2 y O3): Aplicación Del Modelo AirQ+ a La Comarca Del Camp de Tarragona (Cataluña, España). Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, M.S.; Ali, S.M.; Imad-Ud-Din, M.; Subhani, M.A.; Anwar, M.N.; Nizami, A.-S.; Ashraf, U.; Khokhar, M.F. An Emerged Challenge of Air Pollution and Ever-Increasing Particulate Matter in Pakistan; A Critical Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockfelt, L.; Andersson, E.M.; Molnár, P.; Gidhagen, L.; Segersson, D.; Rosengren, A.; Barregard, L.; Sallsten, G. Long-Term Effects of Total and Source-Specific Particulate Air Pollution on Incident Cardiovascular Disease in Gothenburg, Sweden. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannucci, P.M.; Harari, S.; Martinelli, I.; Franchini, M. Effects on Health of Air Pollution: A Narrative Review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2015, 10, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kabir, E.; Kabir, S. A Review on the Human Health Impact of Airborne Particulate Matter. Environ. Int. 2015, 74, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.M. Airborne Particulate Matter. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2020, 378, 20190319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Vásquez, E.; Beleño, L.M.H.; Castrillo-Borja, T.T.; Bolaño-Ortíz, T.R.; Camargo-Caicedo, Y.; Vélez-Pereira, A.M. Airborne Particulate Matter Integral Assessment in Magdalena Department, Colombia: Patterns, Health Impact, and Policy Management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, S.; Ridi, T.B.I.; Miah, M.S.; Sarower, F.; Elahee, S. Implementing Machine Learning Algorithms to Predict Particulate Matter (PM2.5): A Case Study in the Paso Del Norte Region. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.; de Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.; Cardoso, K.R.A.; Fernandes, W.A.; Pavao, H.G. The Impact of Meteorological Variables on Particulate Matter Concentrations. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís, R.; Toro, R.; Gomez, L.; Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; López, M.; Fleming, Z.L.; Fierro, N.; Leiva, M. Long-Term Airborne Particle Pollution Assessment in the City of Coyhaique, Patagonia, Chile. Urban Clim. 2022, 43, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, P.; Izhar, S.; Gupta, T. Deposition Modeling of Ambient Aerosols in Human Respiratory System: Health Implication of Fine Particles Penetration into Pulmonary Region. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019, 10, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, P.; Reynoso, J.; Quaranta, N.; Bardach, A.; Ciapponi, A. Short-Term Exposure to Particulate Matter (PM10 and PM2.5), Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), and Ozone (O3) and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karanasiou, A.; Alastuey, A.; Amato, F.; Renzi, M.; Stafoggia, M.; Tobias, A.; Reche, C.; Forastiere, F.; Gumy, S.; Mudu, P.; et al. Short-Term Health Effects from Outdoor Exposure to Biomass Burning Emissions: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowiecki, P.; Chciałowski, A.; Dąbrowiecka, A.; Badyda, A. Ambient Air Pollution and Risk of Admission Due to Asthma in the Three Largest Urban Agglomerations in Poland: A Time-Stratified, Case-Crossover Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, D.; Fu, L.; Liu, M.; Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Zhen, Q. Source Analysis and Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAHs) in Total Suspended Particulate Matter (TSP) from Bengbu, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Lu, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; He, Y.; Sundell, J.; Norbäck, D. Association between Prenatal Exposure to Industrial Air Pollution and Onset of Early Childhood Ear Infection in China. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 157, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rabha, R.; Chowdhury, M.; Padhy, P.K. Caracterización de Las Fuentes y Especies Químicas de PM10 y Evaluación de Los Riesgos Para La Salud Humana En Zonas Semiurbanas, Urbanas e Industriales de Bengala Occidental (India). Chemosphere 2018, 207, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, P.; Menares, C.; Ramírez, C. PM2.5 Forecasting in Coyhaique, the Most Polluted City in the Americas. Urban Clim. 2020, 32, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Pillarisetti, A.; Oberholzer, A.; Jetter, J.; Mitchell, J.; Cappuccilli, E.; Aamaas, B.; Aunan, K.; Pozzer, A.; Alexander, D. A Global Review of the State of the Evidence of Household Air Pollution’s Contribution to Ambient Fine Particulate Matter and Their Related Health Impacts. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Xing, R.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Men, Y.; Shen, G.; Tao, S. Unclean but Affordable Solid Fuels Effectively Sustained Household Energy Equity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plass Carvallo, M. Contaminación Atmosférica en el sur de Chile: Una Aproximación Cualitativa a Las Prácticas Sociales de Consumo de Leña en Temuco y Padre Las Casas; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Durán Pulgar, S. Contaminación Atmosférica y Consumo de Leña en Valdivia: 2004–2018; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Gallardo, R.I. El Efecto de la Pobreza Energética en la Reducción de Contaminación Atmosférica por Material Particulado 2,5; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huneeus, N. El Aire que Respiramos: Pasado, Presente y Futuro—Contaminación Atmosférica por MP2.5 en el Centro y sur de Chile; Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia (CR)2: Santiago, Chile, 2020; (ANID/FONDAP/15110009). [Google Scholar]

- Quinteros, M.E.; Blanco, E.; Sanabria, J.; Rosas-Diaz, F.; Blazquez, C.A.; Ayala, S.; Cárdenas-R, J.P.; Stone, E.A.; Sybesma, K.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M.; et al. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Particulate Matter and Wood-Smoke Tracers in Temuco, Chile: A City Heavily Impacted by Residential Wood-Burning. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 294, 119529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardones, C.; Cornejo, N. Ex—Post Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Critical Episodes Due to Air Pollution in Southern Chile. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 80, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concha, C.; Rivera, N.M. Wood-Burning Restrictions and Air Pollution: The Case of Air Quality Warnings in Southern Chile. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereceda-Balic, F.; Toledo, M.; Vidal, V.; Guerrero, F.; Diaz-Robles, L.A.; Petit-Breuilh, X.; Lapuerta, M. Emission Factors for PM2.5, CO, CO2, NOx, SO2 and Particle Size Distributions from the Combustion of Wood Species Using a New Controlled Combustion Chamber 3CE. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F.; Yáñez, K.; Vidal, V.; Cereceda-Balic, F. Effects of Wood Moisture on Emission Factors for PM2.5, Particle Numbers and Particulate-Phase PAHs from Eucalyptus Globulus Combustion Using a Controlled Combustion Chamber for Emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, J.; Farias, O.; Quiroz, R.; Yañez, J. Emission Factors of Particulate Matter, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, and Levoglucosan from Wood Combustion in South-Central Chile. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2017, 67, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. Informe del Estado del Medio Ambiente 2024; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quinteros, M.E.; Blazquez, C.; Ayala, S.; Kilby, D.; Cárdenas-R, J.P.; Ossa, X.; Rosas-Diaz, F.; Stone, E.A.; Blanco, E.; Delgado-Saborit, J.-M.; et al. Development of Spatio-Temporal Land Use Regression Models for Fine Particulate Matter and Wood-Burning Tracers in Temuco, Chile. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 19473–19486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Energía de Chile. Informe Balance Nacional de Energía 2020; Ministerio de Energía de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Basoa, K.; Fleming, Z.L.; Leiva, M.A.; Concha, C.; Menares, C. Current Status, Trends, and Future Directions in Chilean Air Quality: A Data-Driven Perspective. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning; Lulu.com: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-244-76852-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente Planes de Prevención y/o Descontaminación Atmosférica (PPDA). Available online: https://ppda.mma.gob.cl/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Bates, J.T.; Fang, T.; Verma, V.; Zeng, L.; Weber, R.J.; Tolbert, P.E.; Abrams, J.Y.; Sarnat, S.E.; Klein, M.; Mulholland, J.A.; et al. Review of Acellular Assays of Ambient Particulate Matter Oxidative Potential: Methods and Relationships with Composition, Sources, and Health Effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4003–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.T.; Weber, R.J.; Abrams, J.; Verma, V.; Fang, T.; Klein, M.; Strickland, M.J.; Sarnat, S.E.; Chang, H.H.; Mulholland, J.A.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Linked to Sources of Atmospheric Particulate Matter and Cardiorespiratory Effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 13605–13612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilhore, U.K.; Simaiya, S.; Singh, R.K.; Baqasah, A.M.; Alroobaea, R.; Alsafyani, M.; Alhazmi, A.; Khan, M.D.M. Advanced Air Quality Prediction Using Multimodal Data and Dynamic Modeling Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, C.-M.; Carbureanu, M.; Stancu, A. Data-Driven Approaches for Predicting and Forecasting Air Quality in Urban Areas. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramsch, E.; Cáceres, D.; Oyola, P.; Reyes, F.; Vásquez, Y.; Rubio, M.A.; Sánchez, G. Influencia de La Inversión Térmica Superficial y de Subsidencia En La Concentración de PM2.5 y Carbono Negro. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 98, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R.; Ihshaish, H.; Deza, J.I. Wind Power Ramp Characterisation and Forecasting Using Numerical Weather Prediction and Machine Learning Models; SSRN: Rochester, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boukabara, S.-A.; Krasnopolsky, V.; Stewart, J.Q.; Maddy, E.S.; Shahroudi, N.; Hoffman, R.N. Leveraging Modern Artificial Intelligence for Remote Sensing and NWP: Benefits and Challenges. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, ES473–ES491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagasio, M.; Pulvirenti, L.; Parodi, A.; Boni, G.; Pierdicca, N.; Venuti, G.; Realini, E.; Tagliaferro, G.; Barindelli, S.; Rommen, B. Effect of the Ingestion in the WRF Model of Different Sentinel-Derived and GNSS-Derived Products: Analysis of the Forecasts of a High Impact Weather Event. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 52, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-B.; Lee, J.-B.; Koo, Y.-S.; Kwon, H.-Y.; Choi, M.-H.; Park, H.-J.; Lee, D.-G. Development of a Deep Neural Network for Predicting 6 h Average PM2.5 Concentrations up to 2 Subsequent Days Using Various Training Data. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 3797–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotzge, J.A.; Berchoff, D.; Carlis, D.L.; Carr, F.H.; Carr, R.H.; Gerth, J.J.; Gross, B.D.; Hamill, T.M.; Haupt, S.E.; Jacobs, N.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Numerical Weather Prediction. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E698–E705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, X.; DelSole, T.; Ravikumar, P.; Banerjee, A. Sub-Seasonal Climate Forecasting via Machine Learning: Challenges, Analysis, and Advances. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2021, 35, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, F.; Yánez, D.; Viñán-Guerrero, P.; A Díaz-Robles, L.; Oyaneder, M.; Reinoso, N.; Billartello, L.; Espinoza-Pérez, A.; Espinoza-Pérez, L.; Pino-Cortés, E. Enhancing Air Quality Predictions in Chile: Integrating ARIMA and Artificial Neural Network Models for Quintero and Coyhaique Cities. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; De Linares, C.; Belmonte, J. Aerobiological Modeling I: A Review of Predictive Models. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; De Linares, C.; Canela, M.-A.; Belmonte, J. Logistic Regression Models for Predicting Daily Airborne Alternaria and Cladosporium Concentration Levels in Catalonia (NE Spain). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 1541–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía Martínez, N.; Montes Martín, L.M. Application of Statistical Modeling Techniques for PM10 Levels Forecast in Bogotá; Universidad de los Andes: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; De Linares, C.; Canela, M.A.; Belmonte, J. A Comparison of Models for the Forecast of Daily Concentration Thresholds of Airborne Fungal Spores. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Bracero, M.; Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; Markey, E.; Clancy, J.H.; Sarda-Estève, R.; O’Connor, D.J. Comparative Analysis of Grass Pollen Dynamics in Urban and Rural Ireland: Identifying Key Sources and Optimizing Prediction Models. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, L.V.; Miranda, A.G.B. Short Term Forecasting of Persistent Air Quality Deterioration Events in the Metropolis of Sao Paulo. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueftan, A.; Sommerhoff, J.; González, A.D. Firewood Demand and Energy Policy in South-Central Chile. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 33, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, A.; Ridley, I. Efectos de La Combustión a Leña En La Calidad Del Aire Intradomiciliario: La Ciudad de Temuco Como Caso de Estudio. Rev. INVI 2013, 28, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile. Decreto Supremo No 12 Establece Norma Primaria de Calidad Ambiental Para Material Particulado Fino Respirable MP2.5; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile. Decreto Supremo No 12 Establece Norma Primaria de Calidad Ambiental Para Material Particulado Fino Respirable MP10; Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Real, R.; Barbosa, A.M.; Vargas, J.M. Obtaining Environmental Favourability Functions from Logistic Regression. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2006, 13, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Sharma, S.; Pant, K. Evaluation of Machine Learning Algorithms for Air Quality Index (AQI) Prediction. J. Reliab. Stat. Stud. 2023, 16, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matara, C.M.; Nyambane, S.O.; Yusuf, A.O.; Ochungo, E.A.; Khattak, A. Classification of Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Concentrations Using Feature Selection and Machine Learning Strategies. LOGI Sci. J. Transp. Logist. 2024, 15, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalzal, J.; Liu, Y.; Smargiassi, A.; Hatzopoulou, M. Improving Residential Wood Burning Emission Inventories with the Integration of Readily Available Data Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, A.; Ciupek, K.; Butterfield, D.; Fuller, G.W. Long-Term Trends in Particulate Matter from Wood Burning in the United Kingdom: Dependence on Weather and Social Factors. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 314, 120105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kangas, L.; Kukkonen, J.; Kauhaniemi, M.; Riikonen, K.; Sofiev, M.; Kousa, A.; Niemi, J.V.; Karppinen, A. The Contribution of Residential Wood Combustion to the PM2.5 Concentrations in the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 1489–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Pettersson, L.H.; Esau, I. Dispersion of Particulate Matter (PM2.5) from Wood Combustion for Residential Heating: Optimization of Mitigation Actions Based on Large-Eddy Simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 12463–12477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orru, H.; Olstrup, H.; Kukkonen, J.; López-Aparicio, S.; Segersson, D.; Geels, C.; Tamm, T.; Riikonen, K.; Maragkidou, A.; Sigsgaard, T.; et al. Health Impacts of PM2.5 Originating from Residential Wood Combustion in Four Nordic Cities. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, J.; López-Aparicio, S.; Segersson, D.; Geels, C.; Kangas, L.; Kauhaniemi, M.; Maragkidou, A.; Jensen, A.; Assmuth, T.; Karppinen, A.; et al. The Influence of Residential Wood Combustion on the Concentrations of PM2.5 in Four Nordic Cities. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 4333–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolahti, M.; Lehtomäki, H.; Karvosenoja, N.; Paunu, V.-V.; Korhonen, A.; Kukkonen, J.; Kupiainen, K.; Kangas, L.; Karppinen, A.; Hänninen, O. Residential Wood Combustion in Finland: PM2.5 Emissions and Health Impacts with and without Abatement Measures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, F.; Ahumada, S.; Rojas, F.; Oyola, P.; Vásquez, Y.; Aguilera, C.; Henriquez, A.; Gramsch, E.; Kang, C.-M.; Saarikoski, S.; et al. Impact of Biomass Burning on Air Quality in Temuco City, Chile. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2021, 21, 210110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellack, B.; Kuhlbusch, T.; Vázquez, Y.; Reyes, F.; Oyola, P.; Gidhagen, L. Air Pollution Due Residential Wood Burning In Southern Chile And Potential Emission Reduction. ISEE Conf. Abstr. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 2015, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Energía Gobierno de Chile. Estrategia de Transición Energética Residencial; Ministerio de Energía Gobierno de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Energía. División de Planificación Estratégica y Desarrollo Sostenible Cuadro Regional de Consumo, Balance Nacional de Energía BNE 2023; Ministerio de Energía: Santiago, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- van der Gon, H.A.C.D.; Bergström, R.; Fountoukis, C.; Johansson, C.; Pandis, S.N.; Simpson, D.; Visschedijk, A.J.H. Particulate Emissions from Residential Wood Combustion in Europe—Revised Estimates and an Evaluation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 6503–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skreiberg, Ø.; Seljeskog, M.; Kausch, F. A Critical Review and Discussion on Emission Factors for Wood Stoves. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 92, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, O.; Jiménez, J.; Salgado, C. Impacto de La Normativa Ambiental Chilena Sobre El Desarrollo Tecnólogico de Calefactores a Biomasa. In Proceedings of the Congreso Iberoamericano de Ingeniería Mecánica CIBEM, Lisbon, Portugal, 23–26 October 2019; Univesidade Nova de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Glojek, K.; Močnik, G.; Alas, H.D.C.; Cuesta-Mosquera, A.; Drinovec, L.; Gregorič, A.; Ogrin, M.; Weinhold, K.; Ježek, I.; Müller, T.; et al. The Impact of Temperature Inversions on Black Carbon and Particle Mass Concentrations in a Mountainous Area. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 5577–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyamani, H.; Olmo, F.J.; Alados-Arboledas, L. Physical and Optical Properties of Aerosols over an Urban Location in Spain: Seasonal and Diurnal Variability. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandradewi, J.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; Szidat, S.; Perron, N.; Alfarra, M.R.; Lanz, V.A.; Weingartner, E.; Baltensperger, U. Using Aerosol Light Absorption Measurements for the Quantitative Determination of Wood Burning and Traffic Emission Contributions to Particulate Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3316–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C.; Toro, A.R.; Morales, S.R.G.E.; Manzano, C.; Leiva-Guzmán, M.A. Particulate Matter in Urban Areas of South-Central Chile Exceeds Air Quality Standards. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2017, 10, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zender-Świercz, E.; Galiszewska, B.; Telejko, M.; Starzomska, M. The Effect of Temperature and Humidity of Air on the Concentration of Particulate Matter—PM2.5 and PM10. Atmos. Res. 2024, 312, 107733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merenda, B.; Drzeniecka-Osiadacz, A.; Sówka, I.; Sawiński, T.; Samek, L. Influence of Meteorological Conditions on the Variability of Indoor and Outdoor Particulate Matter Concentrations in a Selected Polish Health Resort. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Escobar, C.; Zambrano-Bigiarini, M.; Tolorza, V.; Garreaud, R. Gridded Intensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) Curves: Understanding Precipitation Extremes in a Drying Climate. EGUsphere 2025, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, P. Firewood Heating and Pollution in the South of Chile: A Systems Approach for a Comprehensive Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 33rd International on Passive and Low Energy Architecture Conference: Design to Thrive, PLEA 2017, Edinburgh, UK, 2–5 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schueftan, A.; González, A.D. Reduction of Firewood Consumption by Households in South-Central Chile Associated with Energy Efficiency Programs. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.; Boso, À.; Rodríguez, I.; Hofflinger, Á.; Vallejos-Romero, A. Who Buys Certified Firewood? Individual Determinants of Clean Fuel Adoption for Promoting the Sustainable Energy Transition in Southern Chile. Energ. Sustain. Soc. 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorquera, H.; Villalobos, A.M.; Schauer, J.J. Wood Burning Pollution in Chile: A Tale of Two Mid-Size Cities. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2021, 12, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, À.; Oltra, C.; Hofflinger, Á. Participation in a Programme for Assisted Replacement of Wood-Burning Stoves in Chile: The Role of Sociodemographic Factors, Evaluation of Air Quality and Risk Perception. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, Y.; Ferrada, L.M. Consumo Residencial de Leña, Análisis Para La Ciudad de Osorno En Chile. Idesia 2017, 35, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrada, L.M.; Torres, G.; Montaña, V.; Sáez, N.; Ferrada, L.M.; Torres, G.; Montaña, V.; Sáez, N. Consumo de leña en el centro y sur de Chile: Determinantes y diferencias regionales. Madera Bosques 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Ismail, M.; Fong, S.Y. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) Models for Long Term Pm10 Concentration Forecasting during Different Monsoon Seasons. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2017, 12, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Morantes-Quintana, G.R.; Rincón-Polo, G.; Pérez-Santodomingo, N.A.; Morantes-Quintana, G.R.; Rincón-Polo, G.; Pérez-Santodomingo, N.A. Modelo de Regresión Lineal Múltiple Para Estimar Concentración de PM1. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 2019, 35, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, A.S.; Hazrul, A.H.; Hamid, M.H.A. Prediction Of Pm10 Concentrations Using Logistic Regression Analysis: Case Study In Jerantut. In Multidisciplinary Research as Agent of Change for Industrial Revolution 4.0; European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, M.; Clemente, F.M.; Popovič, A.; Silva, S.; Vanneschi, L. A Machine Learning Approach to Predict Air Quality in California. Complexity 2020, 2020, 8049504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Correa, D.E. Prototipo de Red Neuronal Artificial Para el Pronóstico de Eventos Críticos por Partículas PM2.5 en el Centro de la Ciudad de Manizales; Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores: Cundinamarca, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mardoñez, V.; Pandolfi, M.; Borlaza, L.J.S.; Jaffrezo, J.-L.; Alastuey, A.; Besombes, J.-L.; Isabel, M.R.; Perez, N.; Močnik, G.; Ginot, P.; et al. Source Apportionment Study on Particulate Air Pollution in Two High-Altitude Bolivian Cities: La Paz and El Alto. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 10325–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Campa, A.M.S.; Salvador, P.; Fernández-Camacho, R.; Artiñano, B.; Coz, E.; Márquez, G.; Sánchez-Rodas, D.; de la Rosa, J. Characterization of Biomass Burning from Olive Grove Areas: A Major Source of Organic Aerosol in PM10 of Southwest Europe. Atmos. Res. 2018, 199, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarigiannis, D.A.; Karakitsios, S.P.; Kermenidou, M.; Nikolaki, S.; Zikopoulos, D.; Semelidis, S.; Papagiannakis, A.; Tzimou, R. Total Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter in Cities: The Effect of Biomass Combustion. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, G.W.; Tremper, A.H.; Baker, T.D.; Yttri, K.E.; Butterfield, D. Contribución de La Quema de Madera a Las PM10 En Londres. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 87, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellén, H.; Hakola, H.; Haaparanta, S.; Pietarila, H.; Kauhaniemi, M. Influence of Residential Wood Combustion on Local Air Quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 393, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers-Arriagada, N.; Hoorn, S.V.; Cope, M.; Morgan, G.; Hanigan, I.; Williamson, G.; Johnston, F.H. La Carga de Mortalidad Atribuible a Las Partículas de Humo de Estufas de Leña (PM2.5) En Australia. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers-Arriagada, N.; Palmer, A.J.; Bowman, D.M.; Williamson, G.J.; Johnston, F.H. Health Impacts of Ambient Biomass Smoke in Tasmania, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Schneider, P.; Vogt, M.; Castell, N. Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors for Monitoring Residential Wood Burning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 15162–15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmens, E.O.; Noonan, C.W.; Allen, R.W.; Weiler, E.C.; Ward, T.J. Indoor Particulate Matter in Rural, Wood Stove Heated Homes. Environ. Res. 2015, 138, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Geographical Characteristics | Monitoring Network | Saturate Zone Information | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Quality | Meteorological Condition | |||||||||||||

| Region | Station | Population | Coordinates | Period | %Data (PM10) | %Data (PM25) | Valid Years | Tmin (°C) | Tmax (°C) | Prec (mm) | HR (%) | DS * N° | DS Year | Pollutant |

| Maule | Curico—CRC | 159,968 | 34°59′ S, 71°14′ W | 2014–2024 | 98.5 | 97.2 | 11 | 8.6 | 21.7 | 365.7 | 68.2 | 8 | 2011 | PM10 |

| Ñuble | Puren—PEN | 190,382 | 36°36′ S, 72°06′ W | 2013–2024 | 98.4 | 97.8 | 12 | 7.7 | 20.8 | 563.1 | 70.2 | 36 | 2013 | PM10, PM2.5 |

| Biobío | 21 de mayo —MAY | 219,441 | 37°28′ S, 72°21′ W | 2013–2024 | 98.6 | 97.9 | 12 | 8.6 | 20.3 | 620.9 | 66.9 | 11 | 2015 | PM10, PM2.5 |

| La Araucania | Padre casas II—PLC | 80,656 | 38°46′ S, 72°36′ W | 2014–2024 | 79.8 | 88.7 | 10 | 8.2 | 15.4 | 258.5 | 79.2 | 2 | 2013 | PM2.5 |

| Los Rios | Valdivia—VAL | 170,043 | 39°48′ S, 73°14′ W | 2008–2024 | 84.1 | 72.8 | 15 | 7.6 | 17.5 | 1276.5 | 74.1 | 17 | 2014 | PM10, PM2.5 |

| Los Lagos | Osorno—OSO | 166,455 | 40°34′ S, 73°08′ W | 2009–2024 | 78.4 | 78.5 | 13 | 6.4 | 17 | 1051.9 | 74 | 27 | 2012 | PM10, PM2.5 |

| Aysen | Coyhaique II—COY | 57,823 | 45°34′ S, 72°04′ W | 2014–2024 | 97.6 | 98.1 | 11 | 4.2 | 13.7 | 473.2 | 37.1 | 33/15 | 2012/2016 | PM10, PM2.5 |

| Standard | Pollutants | Good | Regular | Alert | Pre-Emergency | Emergency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCh | PM10 | 0–149 | 150–194 | 195–239 | 240–329 | ≥330 |

| PM2.5 | 0–50 | 51–79 | 80–109 | 110–169 | ≥170 | |

| Int | PM10 | 0–54 | 55–154 | 155–354 | 355–424 | ≥425 |

| PM2.5 | 0–9 | 10–35.4 | 35.5–125.4 | 125.5–225.4 | ≥225.5 | |

| Esp | PM10 | 0–20 | 21–40 | 41–50 | 51–99 | ≥100 |

| PM2.5 | 0–10 | 19–20 | 21–25 | 26–49 | ≥50 |

| Pollutant | Station | Minimum ± SD | Mean ± SD | Maximum ± SD | Absolute Maximum | Peak Date (dd-mm-yy) | P98% | CV | % of National Standard Exceedance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | Annual | |||||||||

| PM10 | CRC | 9.95 ± 1.76 | 44.36 ± 5.25 | 165.82 ± 28.56 | 225.00 | 24-Apr-15 | 120.5 | 0.12 | 1.3 | 18.2 |

| PEN | 9.92 ± 2.18 | 47.33 ± 4.58 | 262.16 ± 40.18 | 330.00 | 28-Apr-15 | 168.0 | 0.10 | 4.8 | 33.3 | |

| MAY | 7.42 ± 2.64 | 48.53 ± 6.67 | 301.20 ± 79.40 | 480.00 | 04-Feb-23 | 174.0 | 0.14 | 4.4 | 50.0 | |

| PLC | 8.48 ± 2.96 | 50.50 ± 8.32 | 252.30 ± 56.83 | 339.00 | 22-May-18 | 186.1 | 0.17 | 6.8 | 33.3 | |

| VAL | 6.49 ± 1.84 | 44.54 ± 10.73 | 218.30 ± 48.21 | 300.35 | 27-May-16 | 168.8 | 0.24 | 4.7 | 23.1 | |

| OSO | 7.12 ± 3.13 | 53.98 ± 19.00 | 347.92 ± 101.11 | 628.00 | 30-Jul-12 | 252.3 | 0.35 | 8.5 | 46.2 | |

| COY | 9.27 ± 4.18 | 62.41 ± 14.06 | 420.91 ± 99.02 | 562.00 | 02-Jun-18 | 283.5 | 0.23 | 11.1 | 72.7 | |

| PM2.5 | CRC | 2.82 ± 1.19 | 24.54 ± 1.90 | 133.65 ± 16.61 | 155.00 | 16-Jun-18 | 92.0 | 0.08 | 13.2 | 100.0 |

| PEN | 2.25 ± 0.72 | 30.61 ± 3.46 | 231.71 ± 40.31 | 289.00 | 17-May-13 | 148.3 | 0.11 | 19.2 | 100.0 | |

| MAY | 2.15 ± 0.91 | 28.70 ± 2.88 | 257.63 ± 69.17 | 434.00 | 04-Feb-23 | 143.6 | 0.10 | 15.9 | 100.0 | |

| PLC | 1.72 ± 0.65 | 39.18 ± 6.89 | 239.35 ± 60.58 | 319.00 | 22-May-18 | 176.0 | 0.18 | 26.0 | 100.0 | |

| VAL | 2.81 ± 1.86 | 32.48 ± 5.50 | 187.43 ± 42.48 | 277.28 | 24-Jul-09 | 131.2 | 0.17 | 22.2 | 100.0 | |

| OSO | 2.88 ± 2.56 | 38.29 ± 8.53 | 310.08 ± 78.78 | 474.00 | 16-Jul-12 | 192.6 | 0.22 | 22.9 | 100.0 | |

| COY | 2.34 ± 1.18 | 46.20 ± 10.14 | 390.55 ± 98.78 | 543.00 | 02-Jun-18 | 248.0 | 0.22 | 27.7 | 100.0 | |

| Pollutant | Category 1 | NCh | INT | ESP | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC | PEN | MAY | COY | CRC | PEN | MAY | COY | CRC | PEN | MAY | COY | ||

| PM10 | Good | 99.4 | 97.3 | 97.4 | 94.6 | 80.3 | 76.9 | 81.0 | 71.8 | 15.6 | 13.7 | 22.4 | 31.0 |

| Regular | 0.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 5.3 | 18.7 | 22.5 | 18.6 | 27.5 | 81.4 | 84.2 | 75.3 | 66.3 | |

| Alert | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 33.8 | 37.6 | 30.8 | 36.7 | |

| Pre-emergency | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 21.9 | 25.8 | 22.8 | 30.4 | |

| Emergency | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 13.3 | |

| PM2.5 | Good | 87.4 | 84.4 | 86.1 | 75.2 | 36.0 | 40.3 | 40.0 | 29.4 | 41.3 | 44.0 | 45.6 | 32.3 |

| Regular | 11.6 | 15.5 | 13.5 | 24.5 | 58.7 | 56.0 | 54.4 | 67.7 | 54.2 | 53.1 | 50.6 | 65.5 | |

| Alert | 3.9 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 14.3 | 19.6 | 24.3 | 20.9 | 32.8 | 32.6 | 36.4 | 32.6 | 48.8 | |

| Pre-emergency | 0.7 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 8.1 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 6.0 | 27.9 | 32.9 | 28.5 | 41.7 | |

| Emergency | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 13.5 | 16.3 | 14.1 | 25.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vélez-Pereira, A.M.; Núñez-Magaña, N.; Barreau, D.; Bremer, K.; O’Connor, D.J. Simplifying Air Quality Forecasting: Logistic Regression for Predicting Particulate Matter in Chile. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121377

Vélez-Pereira AM, Núñez-Magaña N, Barreau D, Bremer K, O’Connor DJ. Simplifying Air Quality Forecasting: Logistic Regression for Predicting Particulate Matter in Chile. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121377

Chicago/Turabian StyleVélez-Pereira, Andrés M., Nicole Núñez-Magaña, Danay Barreau, Karim Bremer, and David J. O’Connor. 2025. "Simplifying Air Quality Forecasting: Logistic Regression for Predicting Particulate Matter in Chile" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121377

APA StyleVélez-Pereira, A. M., Núñez-Magaña, N., Barreau, D., Bremer, K., & O’Connor, D. J. (2025). Simplifying Air Quality Forecasting: Logistic Regression for Predicting Particulate Matter in Chile. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1377. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121377