Digitalization in Air Pollution Control: Key Strategies for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in the Energy Transition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Model Construction

3.2. Model Construction

- is the intercept (constant term);

- , , , are the coefficients for each independent variable (GDP, clean energy, digitalization, and urbanization);

- indicates the error term.

3.3. Empirical Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Quantile–Quantile Normality Assessment

4.2. Quantile ADF and KPSS Test Results

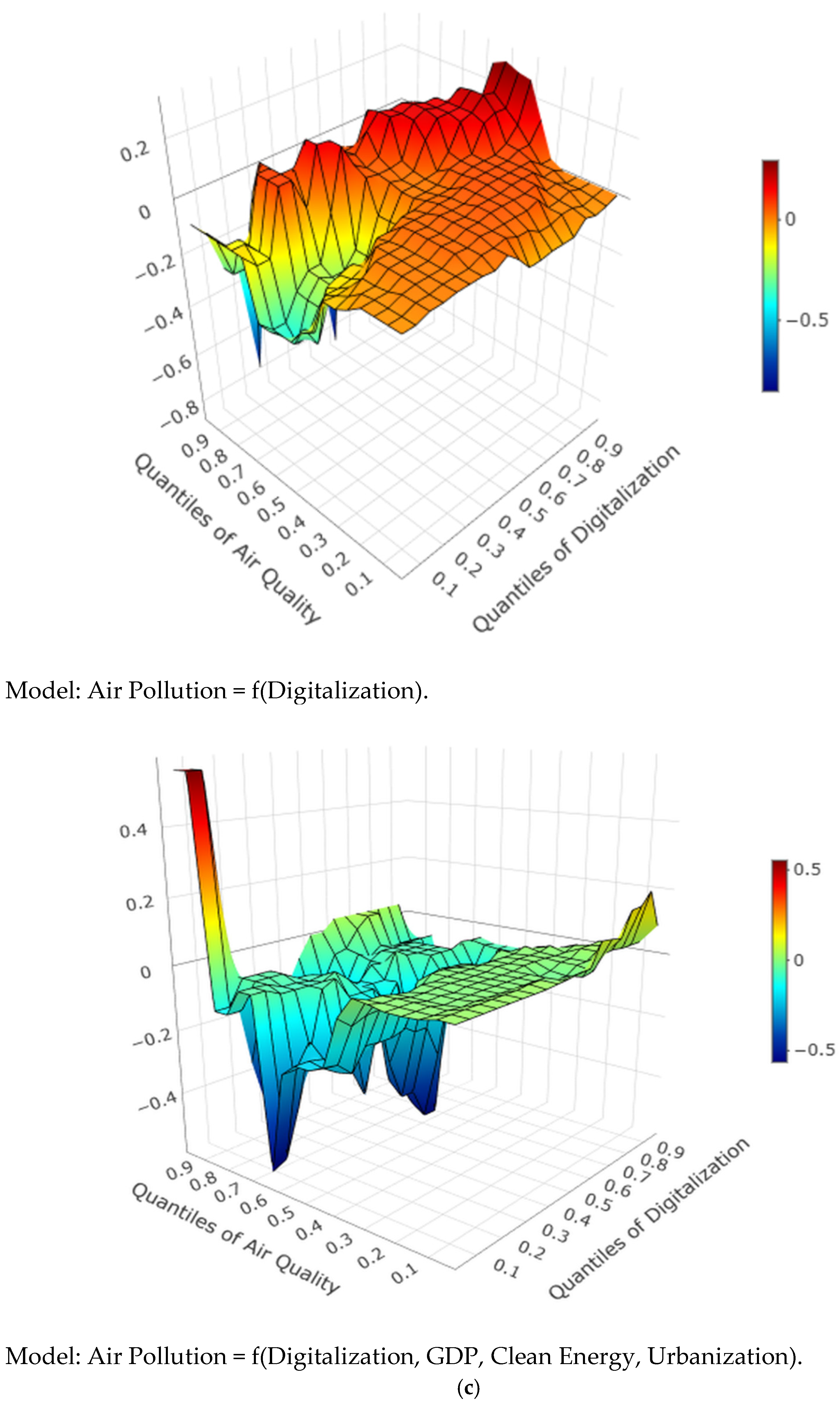

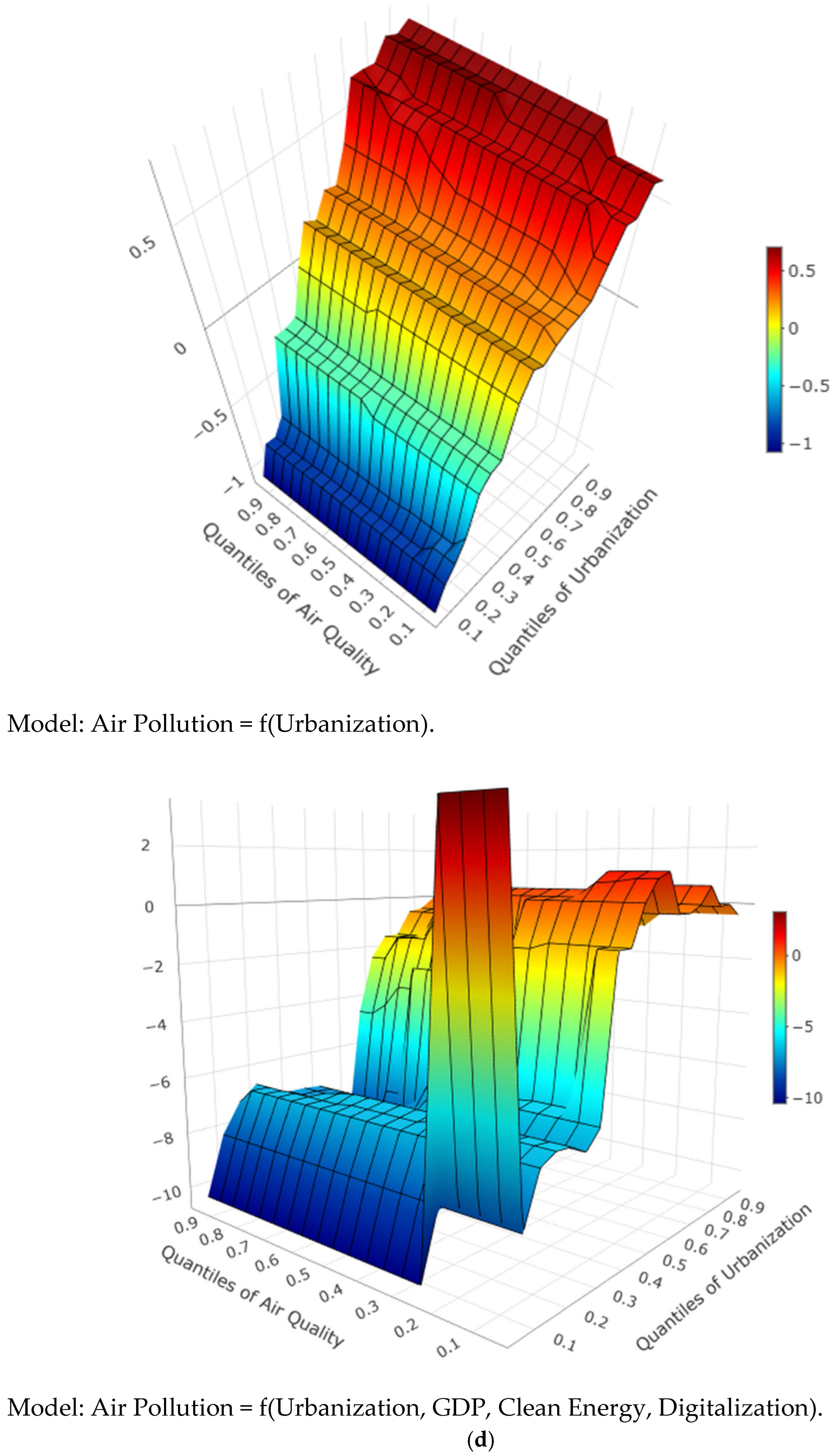

4.3. Key Results from the Multivariate QQR Method

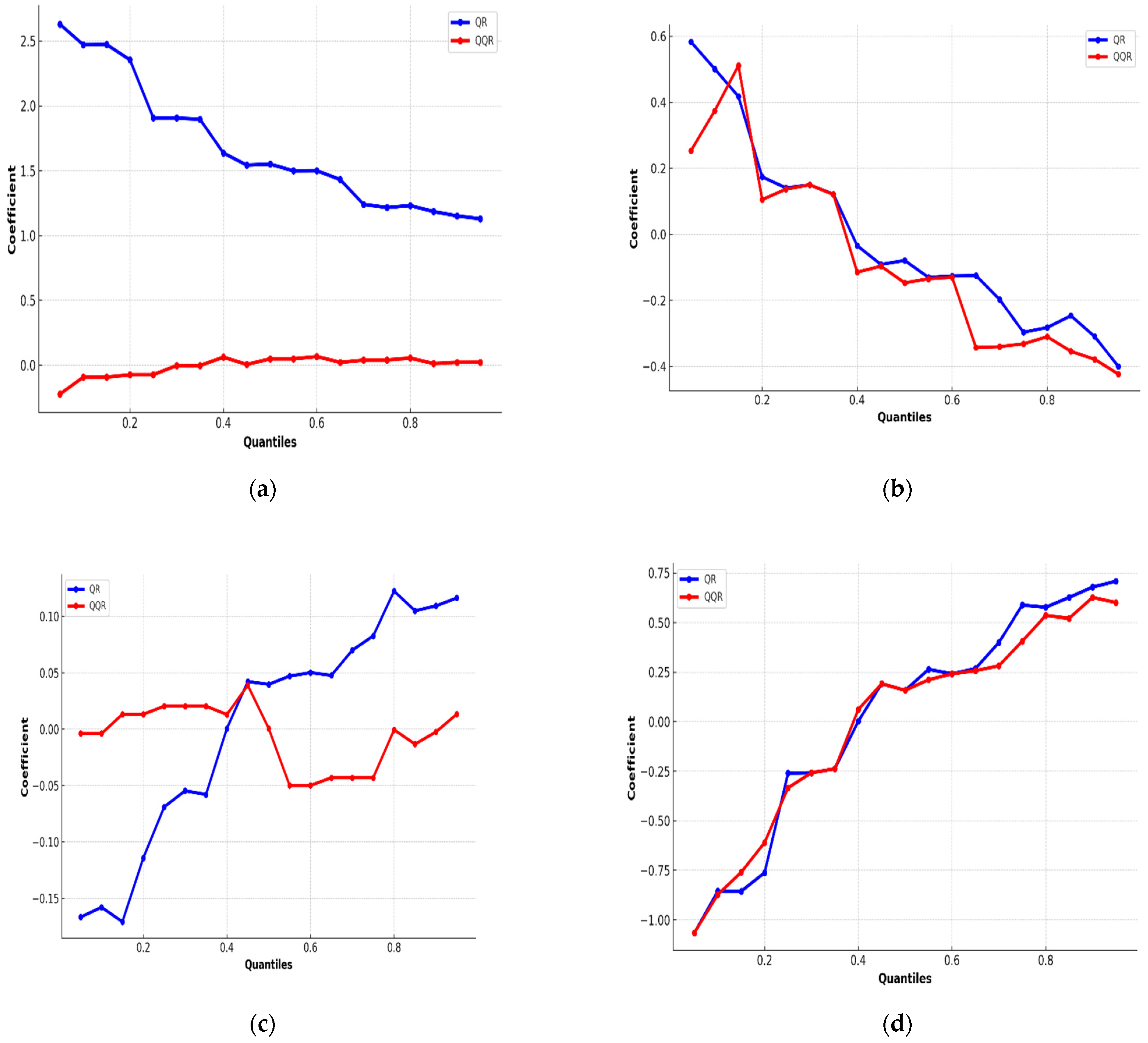

4.4. Robustness Checks: Comparison of QR vs. QQR

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Policy Implications

- Strengthening the Air Quality Monitoring Networks: To improve real-time monitoring of PM 2.5 and other pollutants, one of the most important urgent actions should be to enhance the air quality monitoring networks under NCAP. This will help focus emission reduction initiatives where the marginal benefits of improved air quality are greatest and enable faster responses to high pollution conditions.

- Industrial Energy Efficiency: Policies should focus on improving energy efficiency in essential industrial sectors and/or those that contribute significantly to emissions in the near term. Promoting the use of clean technology in industry and offering incentives to make it greener are two ways to achieve this. The National Mission on Enhanced Energy Efficiency (NMEEE) in India already includes these sorts of programs; it could be expanded to more strictly enforce energy-efficient behaviors.

- Control of Polluting Industries: Industrial pollution could be immediately reduced by enforcing strict emission standards and providing incentives for investment in cleaner technology. Carbon pricing and the development of incentives for clean manufacturing techniques are other possible policy measures.

- Infrastructure for Digital Energy: India should concentrate on creating digital energy infrastructure that integrates renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, in order to support the long-term transition to clean energy. Among the digital technologies that may help manage energy consumption properly and reduce emissions are smart grids, Internet of Things pollution sensors, and real-time air quality monitoring.

- Green Digitalization: All industries should support and implement a “horizonal” approach to green digital technology. By increasing energy efficiency using tools like green data centers and by using energy management platforms, for example, the digitalization path can and should be coupled with the green energy transition. A simultaneous approach to digitalization and clean energy may maximize their respective environmental potential, leading to a more technologically sophisticated and sustainable economy.

- Green Infrastructure and Urban Planning: One of the main causes of pollution is urbanization. The development of green infrastructure in Indian cities, such as green roofs, eco-friendly urban transit options, and integrated renewable power production, should be a part of the country’s long-term urban planning. More of a push for energy-efficient buildings and stricter regulations on transportation emissions should go hand in hand with all of this.

- Long-term vision: Emphasize that, despite the challenges of transitioning to clean energy and digitalization, particularly in providing equal access to technology and infrastructure, the long-term benefits of transitioning India’s economy to a cleaner and more sustainable one cannot be overstated. This indicates that these strategies can synergistically contribute to cleaner air, better public health, and a climate-safe future for India in the global fight against climate change.

5.2. Future Direction and Limitation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ambient (Outdoor) Air Pollution. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- New State of Global Air Report Finds Air Pollution Is Second Leading Risk Factor for Death Worldwide|Health Effects Institute. Available online: https://www.healtheffects.org/announcements/new-state-global-air-report-finds-air-pollution-second-leading-risk-factor-death (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Data Review: How Many People Die from Air Pollution?—Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/data-review-air-pollution-deaths (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Lai, H.-C.; Dai, Y.-T.; Mkasimongwa, S.W.; Hsiao, M.-C.; Lai, H.-C.; Dai, Y.-T.; Mkasimongwa, S.W.; Hsiao, M.-C.; Lai, L.-W. The Impact of Atmospheric Synoptic Weather Condition and Long-Range Transportation of Air Mass on Extreme PM10 Concentration Events. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Stettler, M.E.J. A Novel Multi-Pollutant Space-Time Learning Network for Air Pollution Inference. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Petetin, H.; Méndez Turrubiates, R.F.; Achebak, H.; Pérez García-Pando, C.; Ballester, J. Population Exposure to Multiple Air Pollutants and Its Compound Episodes in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentschler, J.; Leonova, N. Global Air Pollution Exposure and Poverty. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Duan, L. Can Informal Environmental Regulation Restrain Air Pollution?—Evidence from Media Environmental Coverage. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhu, J. The Role of Renewable Energy Technological Innovation on Climate Change: Empirical Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Wu, D. Heatwaves Worsen the Air Pollution from Energy Systems: Empirical Evidence from Balancing Authorities in the United States. Energy Econ. 2025, 148, 108677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhu, L. Does Renewable Energy Technological Innovation Control China’s Air Pollution? A Spatial Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Debanth, A. Impact of CO2 Emission on Life Expectancy in India: An Autoregressive Distributive Lag (ARDL) Bound Test Approach. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.F.; Crespo, C.F.; Silva, G.M.; Nicola, M.B. Innovation in Times of Crisis: The Relevance of Digitalization and Early Internationalization Strategies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 188, 122283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Kar, A.K.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Grover, P.; Abbas, R.; Andreini, D.; Abumoghli, I.; Barlette, Y.; Bunker, D.; et al. Climate Change and COP26: Are Digital Technologies and Information Management Part of the Problem or the Solution? An Editorial Reflection and Call to Action. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 63, 102456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Y. Technology-Driven Carbon Reduction: Analyzing the Impact of Digital Technology on China’s Carbon Emission and Its Mechanism. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Gonzalez, E.S. Understanding the Adoption of Industry 4.0 Technologies in Improving Environmental Sustainability. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Chen, Y. The Collision of Digital and Green: Digital Transformation and Green Economic Efficiency. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impact of Digital Technologies|United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/un75/impact-digital-technologies (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Lakhan, A.; Hamouda, H.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Alyahya, S.; Mohammed, M.A. Digital Healthcare Framework for Patients with Disabilities Based on Deep Federated Learning Schemes. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 169, 107845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, X. Intelligent Manufacturing, Green Technological Innovation and Environmental Pollution. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wei, X.; Yan, G.; He, X. The Impact of Fintech Development on Air Pollution. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Ullah, S. Towards the Goal of Going Green: Do Green Growth and Innovation Matter for Environmental Sustainability in Pakistan. Energy 2023, 285, 129263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, J.; Jo, K. The Role of Digital Technology in Climate Technology Innovation. KDI J. Econ. Policy 2023, 45, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Yasmeen, H.; Ali, S.; Ismail, H.; Zameer, H. Fintech Development, Renewable Energy Consumption, Government Effectiveness and Management of Natural Resources along the Belt and Road Countries. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, E.; Lupa, M.; Zaręba, M.; Eglí Nska, W.; Danek, T.; Mishra, A.K.; Pl, A.K.M. Emergency Medical Interventions in Areas with High Air Pollution: A Case Study from Małopolska Voivodeship, Poland. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, G.N.; Obieri, O.C.; Usman, O. Modelling the Air Pollution Induced Health Effects of Energy Consumption across Varied Spaces in OECD Countries: An Asymmetric Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, Y. Digital Empowerment: Unlocking the “synergy Barrier” of Government-Enterprise-Public Air Pollution Control. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 4846–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Development Indicators (WDI) 2023. Available online: https://Databank.Worldbank.Org/Source/World-Development-Indicators (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- OWID. Our World in Data. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Adebayo, T.S.; Özkan, O. Evaluating the Role of Financial Globalization and Oil Consumption on Ecological Quality: A New Perspective from Quantile-on-Quantile Granger Causality. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broock, W.A.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Dechert, W.D.; LeBaron, B. A Test for Independence Based on the Correlation Dimension. Econom. Rev. 1996, 15, 197–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.; Zhou, H. Oil Prices, US Stock Return, and the Dependence between Their Quantiles. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, R.; Granger, C.W.J.; Schmalensee, R. Advertising and Aggregate Consumption: An Analysis of Causality. Econometrica 1980, 48, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, B.; Xu, B. Modeling the Impact of Energy Abundance on Economic Growth and CO2 Emissions by Quantile Regression: Evidence from China. Energy 2021, 227, 120416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description | Measurements | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Pollution | PM2.5 air pollution | PM2.5 air pollution, mean annual exposure (micrograms per cubic meter) | WDI [28] |

| GDP | Economic growth | Per capita (constant 2015 US dollars) | WDI (2023) [28] |

| Clean Energy | Renewable energy consumption | % of total energy consumption | OWID [29] |

| Digitalization | ICT | Mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people | OWID [29] |

| Urbanization | Population growth | % Of total Population | WDI (2023) [28] |

| Air Pollution | GDP | Clean Energy | Digitalization | Urbanization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.694606 | 3.134494 | 1.696886 | 1.960196 | 1.435748 |

| Median | 1.697722 | 3.110325 | 1.705222 | 1.951338 | 1.432685 |

| Maximum | 1.776085 | 3.377026 | 1.814913 | 2.310693 | 1.508466 |

| Minimum | 1.584724 | 2.923087 | 1.569666 | 1.648116 | 1.373229 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.041848 | 0.146666 | 0.074615 | 0.200185 | 0.040764 |

| Skewness | −0.558777 | 0.267597 | −0.188410 | 0.105673 | 0.180249 |

| Kurtosis | 3.788081 | 1.700409 | 1.931184 | 1.956475 | 1.783475 |

| Jarque–Bera | 9.661674 | 10.20608 | 6.635868 | 5.856995 | 8.317769 |

| Probability | 0.007980 | 0.006078 | 0.036228 | 0.053477 | 0.015625 |

| Dimensions | Air Pollution | GDP | Clean Energy | Digitalization | Urbanization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 | 17.892 | 50.091 | 49.449 | 46.872 | 53.142 |

| M3 | 17.912 | 53.417 | 52.494 | 48.920 | 56.582 |

| M4 | 18.877 | 57.881 | 56.582 | 51.839 | 61.283 |

| M5 | 18.158 | 64.593 | 62.761 | 56.549 | 68.423 |

| M6 | 21.457 | 73.790 | 71.405 | 63.908 | 78.316 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, S.T.; Long, W.; Fang, H.; Iqbal, K.; Hassan, M.U. Digitalization in Air Pollution Control: Key Strategies for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in the Energy Transition. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121370

Hassan ST, Long W, Fang H, Iqbal K, Hassan MU. Digitalization in Air Pollution Control: Key Strategies for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in the Energy Transition. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121370

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Syed Tauseef, Wang Long, Heyuan Fang, Kashif Iqbal, and Mehboob Ul Hassan. 2025. "Digitalization in Air Pollution Control: Key Strategies for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in the Energy Transition" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121370

APA StyleHassan, S. T., Long, W., Fang, H., Iqbal, K., & Hassan, M. U. (2025). Digitalization in Air Pollution Control: Key Strategies for Achieving Net-Zero Emissions in the Energy Transition. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121370