Observation of the Large Forbush Decrease Event on 1–10 June 2025 at the Tien Shan Cosmic Ray Station

Abstract

1. Introduction

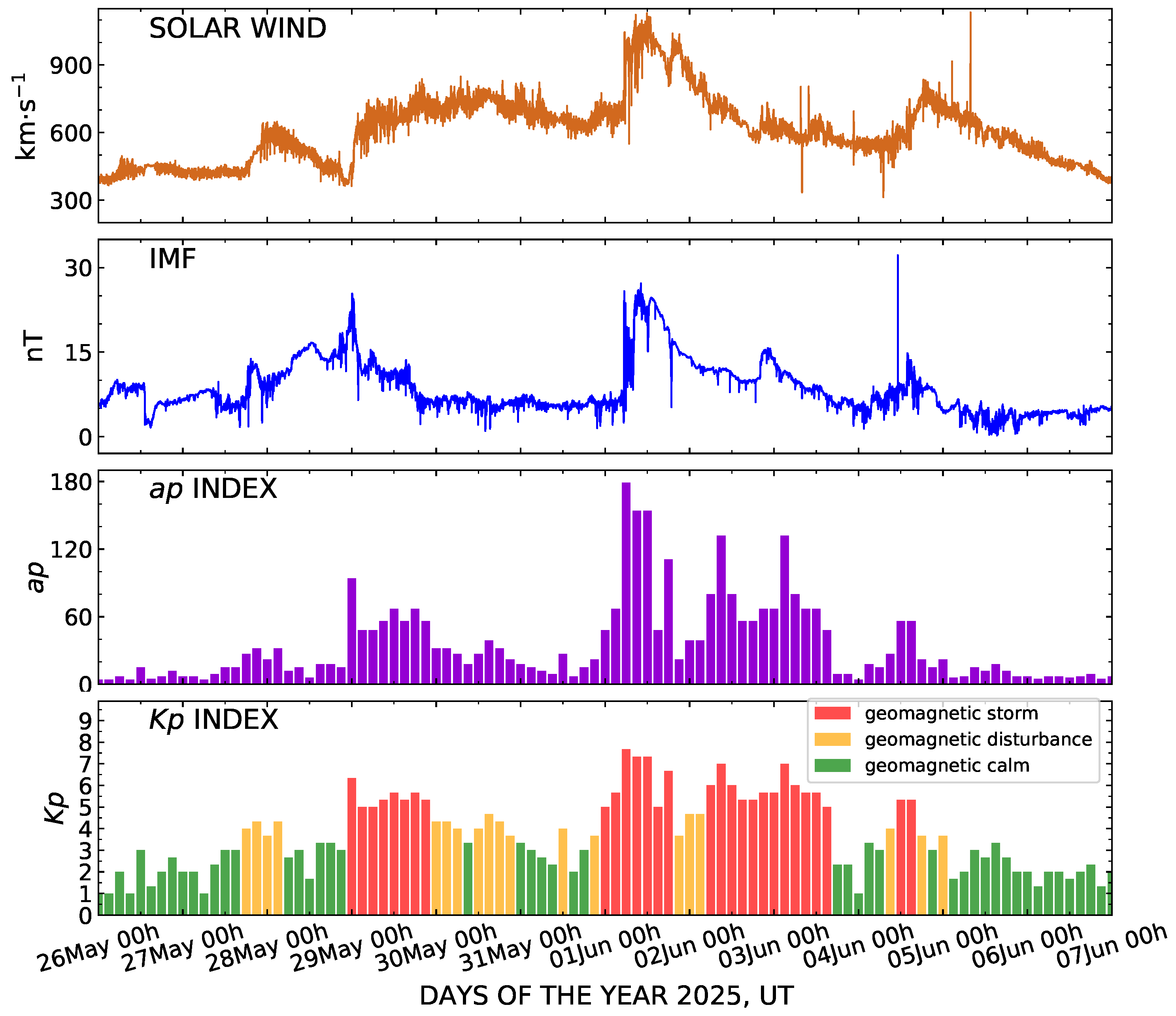

2. The Solar and Geomagnetic Situation

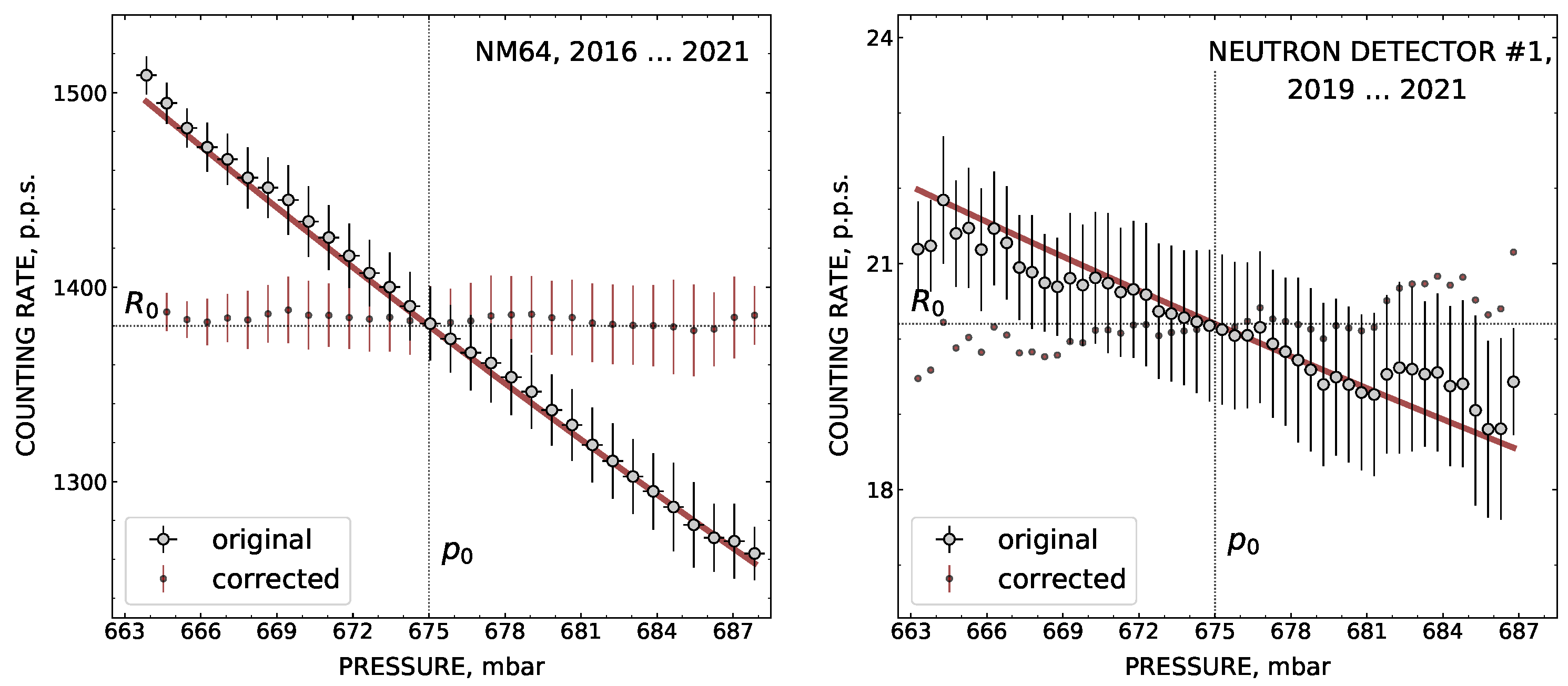

3. Methods

4. The Measurement Data and Discussion

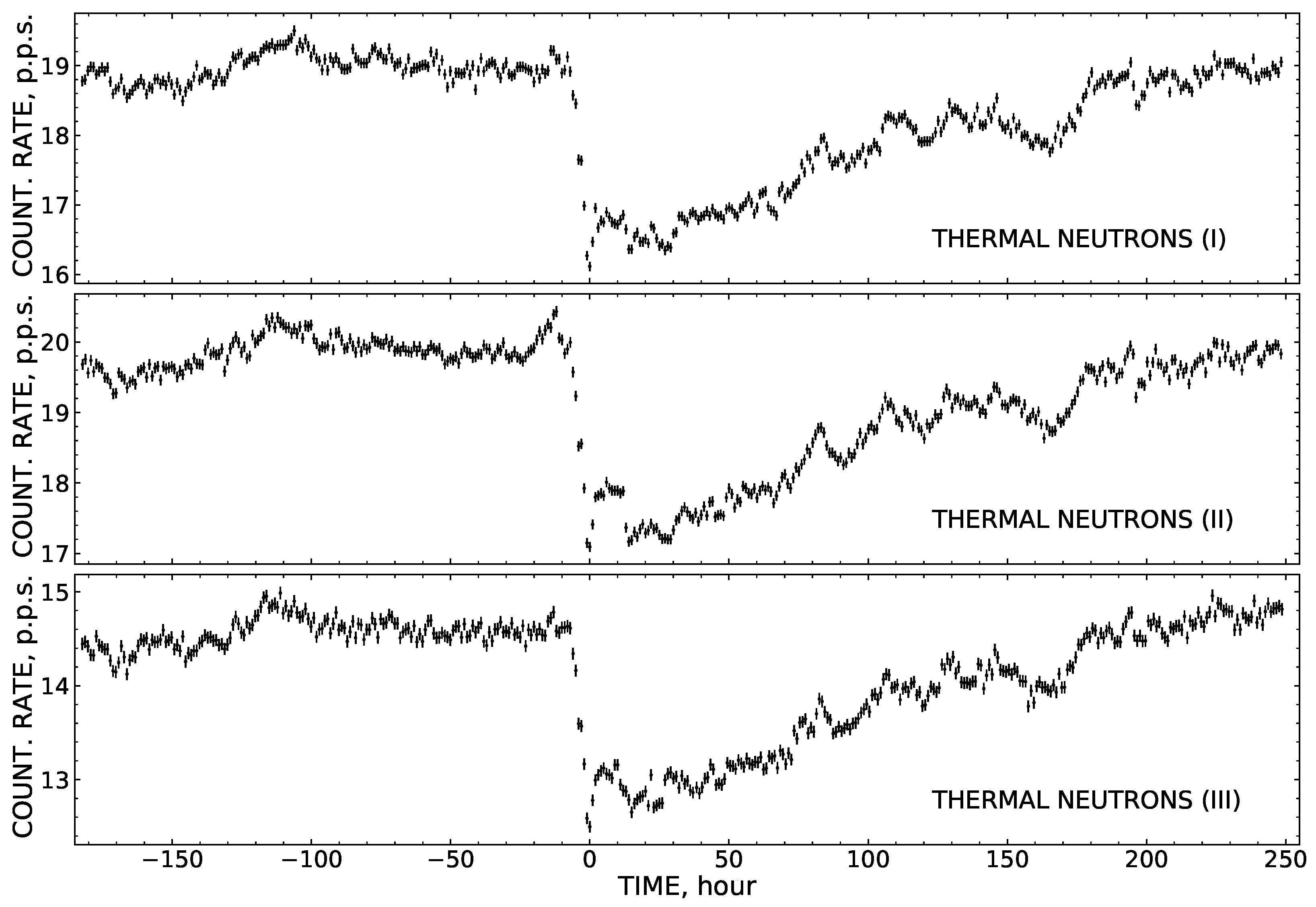

4.1. The Neutron and Gamma Radiation Background in the Environment

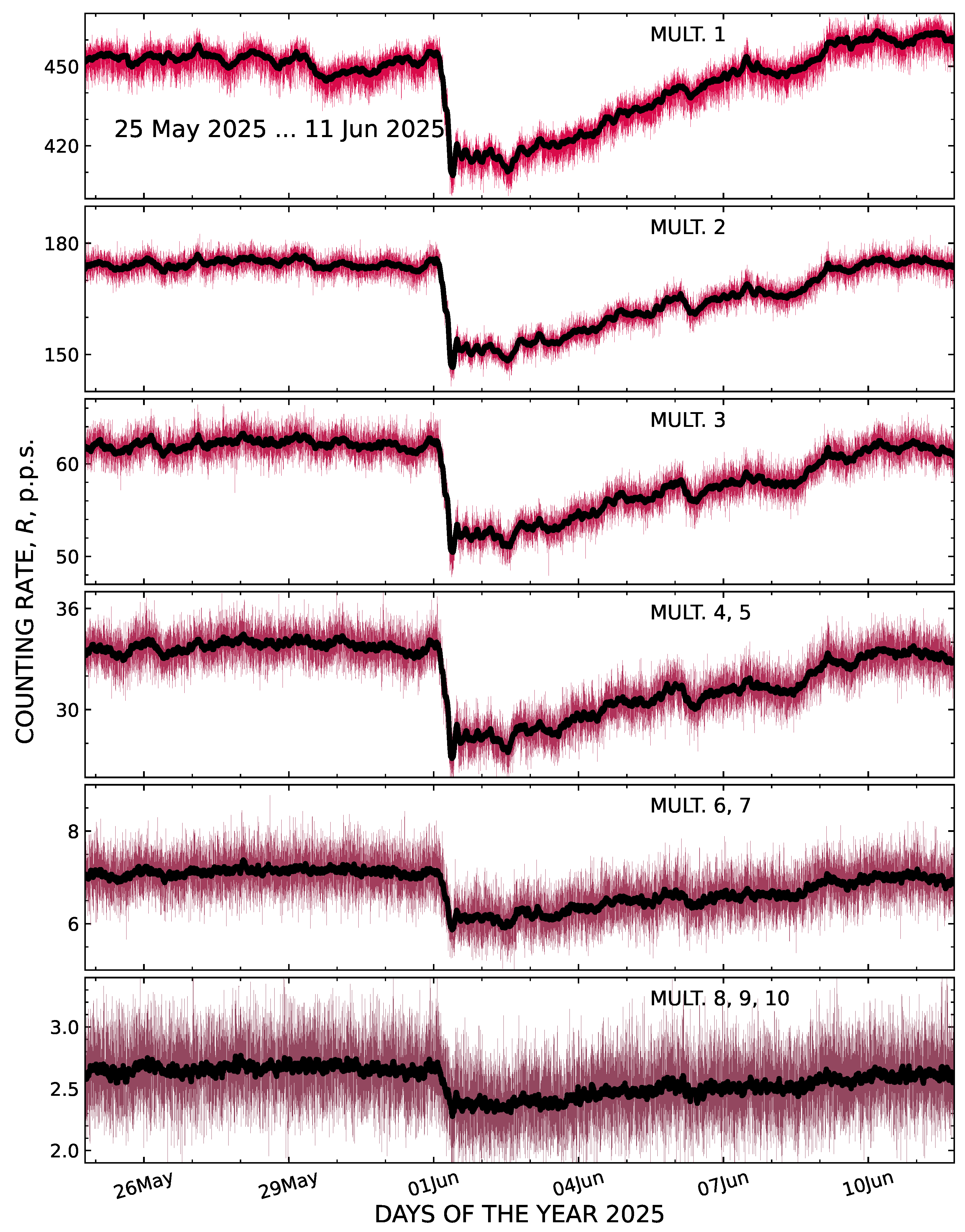

4.2. Intensity of the Events of Multiple-Neutron Generation in the Neutron Supermonitor

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belov, A.V.; Eroshenko, E.A.; Oleneva, V.A.; Struminsky, A.B.; Yanke, V.G. What determines the magnitude of Forbush decreases? Adv. Space. Res. 2001, 27, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, A.V. Forbush effects and their connection with solar, interplanetary and geomagnetic phenomena. Proc. Int. Astron. Union 2008, 4, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieber, J.W.; Evenson, P. Spaceship Earth—An optimized network of neutron monitors. In Proceedings of the 24th International Cosmic Ray Conference, Rome, Italy, 28 August–8 September 1995; Volume 4, p. 1316. [Google Scholar]

- NMDB: Real-Time Database for High Resolution Neutron Monitor Measurements. Available online: http://www.nmdb.eu (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wang, S.; Bindi, V.; Consolandi, C.; Corti, C.; Light, C.; Nikonov, N.; Kuhlman, A. Properties of Forbush decreases with AMS-02 daily proton flux data. Astrophys. J. 2023, 950, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorosheva, D.N.; Arkhangelskaja, I.V.; Borog, V.V. The characteristics of Forbush decreases based on the data from AMS-02 experiment and the fluxes of solar cosmic rays based on GOES-15 data. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2025, 89, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoida, I.; Voronov, S.; Mikhailov, V. Investigations of Forbush decreases in the PAMELA experiment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 798, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagoida, I.; Voronov, S.; Mikhailov, V. Characteristics of Forbush decreases measured by the PAMELA instrument during 2006–2014. Phys. At. Nucl. 2019, 82, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemanno, F.; An, Q.; Azzarello, P.; Carla Tiziana Barbato, F.; Bernardini, P.; Bi, X.; Cai, M.; Casilli, E.; Catanzani, E.; Chang, J.; et al. Observations of Forbush decreases of cosmic-ray electrons and positrons with the Dark Matter Particle Explorer. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2021, 920, L43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, H.V. Cosmic ray decreases and magnetic clouds. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98, 3509–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, H.V. Coronal mass ejections and Forbush decreases. Space Sci. Rev. 2000, 93, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalswamy, N.; Akiyama, S.; Yashiro, S.; Mäkelä, P. Coronal mass ejections from sunspot and non-sunspot regions. In Magnetic Coupling Between the Interior and the Atmosphere of the Sun; Hasan, S., Rutten, R.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, I.G.; Cane, H.V. Near-Earth Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejections During Solar Cycle 23 (1996–2009): Catalog and Summary of Properties. Sol. Phys. 2010, 264, 189–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Badruddin. Interplanetary coronal mass ejections, associated features, and transient modulation of galactic cosmic rays. Sol. Phys. 2014, 289, 2177–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, A.; Belov, A.; Abunina, M.; Eroshenko, E.; Abunin, A.; Anastasiadis, A.; Patsourakos, S.; Mavromichalaki, H. Interplanetary coronal mass ejections as the driver of non-recurrent Forbush decreases. Astrophys. J. 2020, 890, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkumyan, A.A.; Belov, A.V.; Abunina, M.A.; Shlyk, N.S.; Abunin, A.A.; Oleneva, V.A.; Yanke, V. Forbush decreases associated with coronal mass ejections from active and non-active regions: Statistical Comparison. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 515, 4430–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryakunova, O.; Seifullina, B.; Abunina, M.; Shlyk, N.; Abunin, A.; Nikolayevskiy, N.; Tsepakina, I. Forbush effects associated with disappeared solar filaments. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 2073–4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kóta, J.; Jokipii, J.R. Corotating variations of cosmic rays near the south heliospheric pole. Science 1995, 268, 1024–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iucci, N.; Parisi, M.; Storini, M.; Villoresi, G. High-speed solar-wind streams and galactic cosmic-ray modulation. Il Nuov. Cim. C 1979, 2, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, I.G. Energetic particles and corotating interaction regions in the solar wind. Space Sci. Rev. 2004, 111, 267–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunzlaff, P.; Heber, B.; Kopp, A.; Rother, O.; Müller-Mellin, R.; Klassen, A.; Gymez-Herroro, R.; Wimmer-Schweingruber, R. Observations of recurrent cosmic ray decreases during solar cycles 22 and 23. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 26, 3127–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Mursula, K. Hale cycle and long-term trend in variation of galactic cosmic rays related to solar rotation. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 599, A112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, I.G. Solar wind stream interaction regions throughout the heliosphere. Liv. Rev. Sol. Phys. 2018, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajra, R.; Sunny, J.V.; Babu, M.; Nair, A.G. Interplanetary sheaths and corotating interaction regions: A comparative statistical study on their characteristics and geoeffectiveness. Sol. Phys. 2022, 297, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlyk, N.S.; Belov, A.V.; Abunina, M.A.; Belov, S.M.; Abunin, A.A.; Oleneva, V.A.; Yanke, V.G. Some features of interacting solar wind disturbances. Geomagn. Aeron. 2024, 64, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlyk, N.S.; Belov, A.V.; Abunina, M.A.; Abunin, A.A.; Oleneva, V.A.; Yanke, V.G. Forbush decreases caused by paired interacting solar wind disturbances. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 511, 5897–5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbush Effects and Interplanetary Disturbances Database. Available online: https://tools.izmiran.ru/w/feid (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Zusmanovich, A.G.; Kryakunova, O.N.; Shepetov, A.L. Tien-Shan Mountain Cosmic Ray Station of Ionosphere Institute of Kazakhstan Republic. Adv. Space Res. 2009, 44, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepetov, A.; Kryakunova, O.; Mamina, S.; Ryabov, V.; Sadykov, T.; Saduyev, N.; Salikhov, N.; Vildanova, L.; Zhukov, V. Geophysical aspect of cosmic ray studies at the Tien Shan mountain station: Monitoring of radiation background, investigation of atmospheric electricity phenomena in thunderclouds, and the search for earthquake precursor effects. Phys. At. Nucl. 2021, 84, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhov, N.; Argynova, K.; Vildanova, L.; Zhukov, V.; Idrisova, T.; Iskakov, B.; Mamina, S.; Pak, G.; Ryabov, V.; Saduyev, N.; et al. Multichannel monitoring of the radiation background and a search for precursor signals of seismic activity at the Tien Shan Mountain Station. Bull. Lebedev Phys. Inst. 2022, 49, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhov, N.; Shepetov, A.; Pak, G.; Nurakynov, S.; Ryabov, V.; Saduyev, N.; Sadykov, T.; Zhantayev, Z.; Zhukov, V. Monitoring of gamma radiation prior to earthquakes in a study of lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere coupling in Northern Tien Shan. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubenko, A.; Shepetov, A.; Antonova, V.; Borisov, A.; Dalkarov, O.; Kryakunova, O.; Mukashev, K.; Mukhamedshin, R.; Nam, R.; Nikolaevsky, N.; et al. New complex EAS installation of the Tien Shan mountain cosmic ray station. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 2016, 832, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepetov, A.; Chubenko, A.; Iskhakov, B.; Kryakunova, O.; Kalikulov, O.; Mamina, S.; Mukashev, K.; Piscal, V.; Ryabov, V.; Saduyev, N.; et al. Measurements of the low-energy neutron and gamma ray accompaniment of extensive air showers in the knee region of primary cosmic ray spectrum. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2020, 135, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepetov, A.; Antonova, V.; Kalikulov, O.; Kryakunova, O.; Karashtin, A.; Lutsenko, V.; Mamina, S.; Mukashev, K.; Piscal, V.; Ryabov, V.; et al. The prolonged gamma ray enhancement and the short radiation burst events observed in thunderstorms at Tien Shan. Atm. Res. 2021, 248, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepetov, A.; Argynova, K.; Vildanova, L.; Idrisova, T.; Iskakov, B.; Zhukov, V.; Mamina, S.; Saduyev, N.; Sadykov, T.; Ryabov, V. Short-time increases in the gamma ray intensity and electron flux inside thunderclouds as studied at the high-altitude detector point of the Tien-Shan mountain station. Bull. Lebedev Phys. Inst. 2023, 50, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) Project. Available online: https://sohoftp.nascom.nasa.gov/sdb/goes/ace/daily/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences. Geomagnetic Kp Index. Available online: https://kp.gfz.de/en/figures/kp-since-1932 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. Solar Region Summary. Available online: https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-region-summary (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- NOAA/NWS Space Weather Prediction Center. NOAA Shares Imagery from GOES-19 CCOR-1. Available online: https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/news/noaa-shares-imagery-goes-19-ccor-1 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Solar and Heliosphere Observatory Homepage. Available online: https://soho.nascom.nasa.gov (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Hatton, C.J. The neutron monitor. In Progress in Elementary Particle and Cosmic Ray Physics; Wilson, J.G., Wouthuysen, S.A., Eds.; North-Holland Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1971; Volume 10, pp. 3–97. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, H.; Hatton, C.J. Experimental investigation of the NM-64 neutron monitor. Can. J. Phys. 1964, 42, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, H.; Bercovitch, M.; Shea, M.; Magidin, M.; Peterson, R. Attenuation of neutron monitor radiation in the atmosphere. Can. J. Phys. 1968, 46, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, L.I. Meteorological Effects of Cosmic Ray; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1972; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Shepetov, A.; Chubenko, A.; Kryakunova, O.; Nikolayevsky, N.; Salikhov, N.; Yanke, V. The STM32 microcontroller based pulse intensity registration system for the neutron monitor. EPJ Web Conf. 2017, 145, 19002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhov, N.; Pak, G.; Kryakunova, O.; Chubenko, A.; Shepetov, A. An increase of the soft gamma-radiation background by precipitations. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Cosmic Ray Conference, ICRC 2011, Beijing, China, 11–18 August 2011; Volume 11, pp. 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, S.; Huisman, J.A.; Azevedo, E.B. Meteorological and soil surface effects in gamma radiation time series—Implications for assessment of earthquake precursors. J. Environ. Radioact. 2018, 195, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yan, J.; Wang, Q. Monitoring of gamma radiation in a seismic region and its response to seismic events. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 213, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilingarian, A.; Karapetyan, T.; Sargsyan, B. The largest Forbush decrease in 20 years: Preliminary analysis of SEVAN network observations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.B.; Marsden, P.L.; Brooke, G.; Meyer, M.A.; Wolfendale, A.W. Neutron production by cosmic ray protons in lead. Proc. Phys. Soc. 1964, 83, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.L. Neutron production in lead and energy response of neutron monitor. Suppl. Nuovo Cimento 1968, VI, 1177. [Google Scholar]

- Clem, J.M.; Dorman, L.I. Neutron Monitor Response Functions. Space Sci. Rev. 2000, 93, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubenko, A.P.; Shepetov, A.L.; Antonova, V.P.; Kryukov, S.V.; Mukhamedshin, R.A.; Oskomov, V.V.; Piscal, V.V.; Sadykov, T.K.; Sobolevsky, N.N.; Vildanova, L.I.; et al. Multiplicity spectrum of NM64 neutron supermonitor and hadron energy spectrum at mountain level. In Proceedings of the 28th International Cosmic Ray Conference, Tsukuba, Japan, 31 July–7 August 2003; pp. 789–792. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, S.; Munakata, Y.; Tatsuoka, R.; Muraki, Y.; Masuda, K.; Matsubara, Y.; Koi, T.; Sako, T.; Muraba, T.; Tsuchiya, H.; et al. Detection efficiency of a neutron monitor calibrated by an accelerator neutron beam. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 2001, 463, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abunin, A.A.; Pletnikov, E.V.; Shchepetov, A.L.; Yanke, V.G. Efficiency of detection for neutron detectors with different geometries. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2011, 75, 866–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, R. The 1 June 2025 Forbush decrease measured over a range of primary cosmic ray energies. Universe 2025, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Tien-Shan High-Mountain Station’s Database. Available online: http://www.tien-shan.org (accessed on 1 October 2025).

| Instrument | r, 25–28 May 2025 | r, 31 May–2 June 2025 |

|---|---|---|

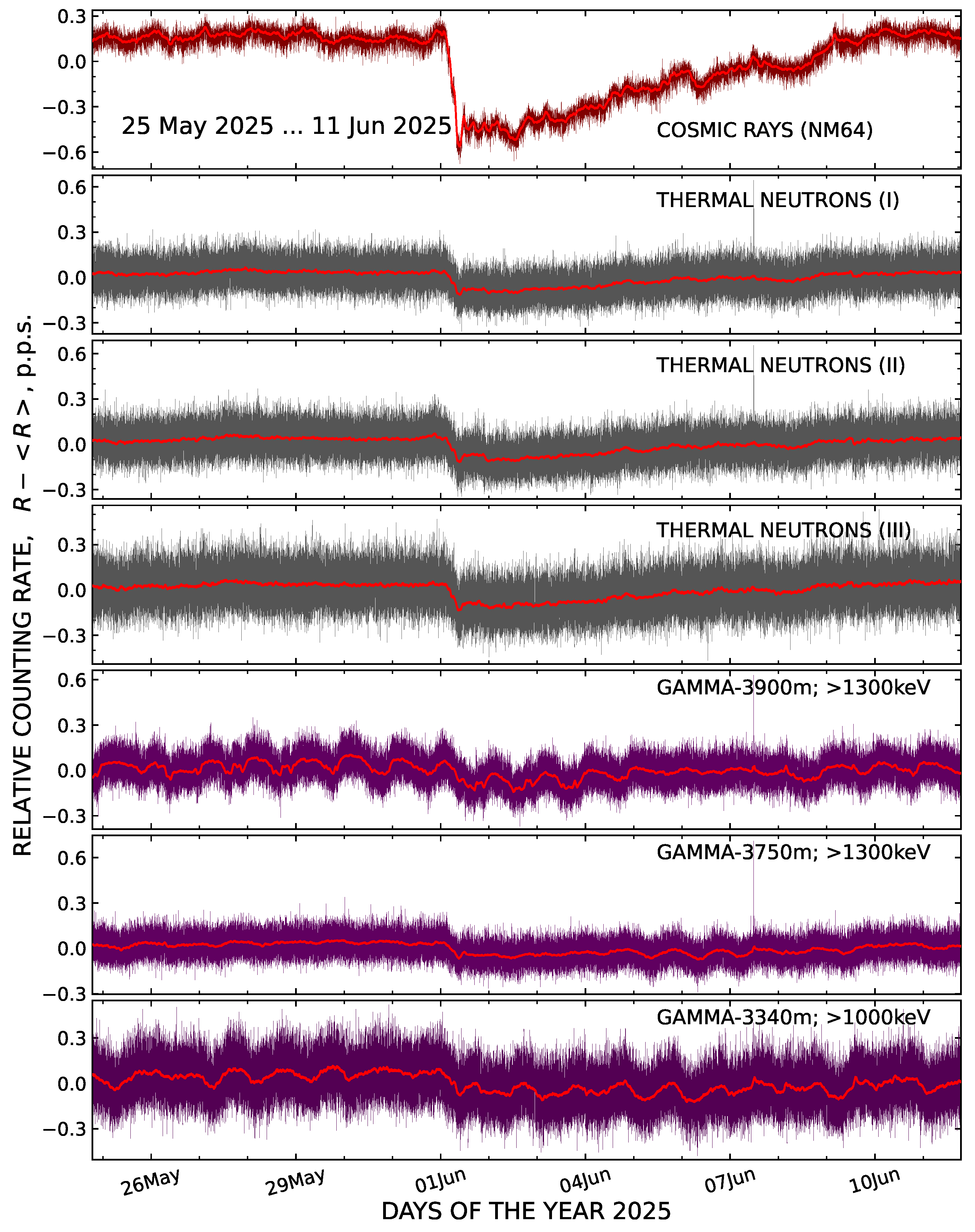

| thermal neutron detectors #1, #2, and #3 | 0.29 0.14 0.23 | 0.99 0.98 0.99 |

| gamma detectors at 3340, 3750, and 3900 m a.s.l. | −0.08 0.18 −0.40 | 0.69 0.64 0.72 |

| Instrument | Background Counting Rate, , p.p.s. | Standard Deviation, , p.p.s. | Magnitude of the Forbush Decrease, , p.p.s. | Relative Magnitude, | Magnitude in Standard Deviations, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

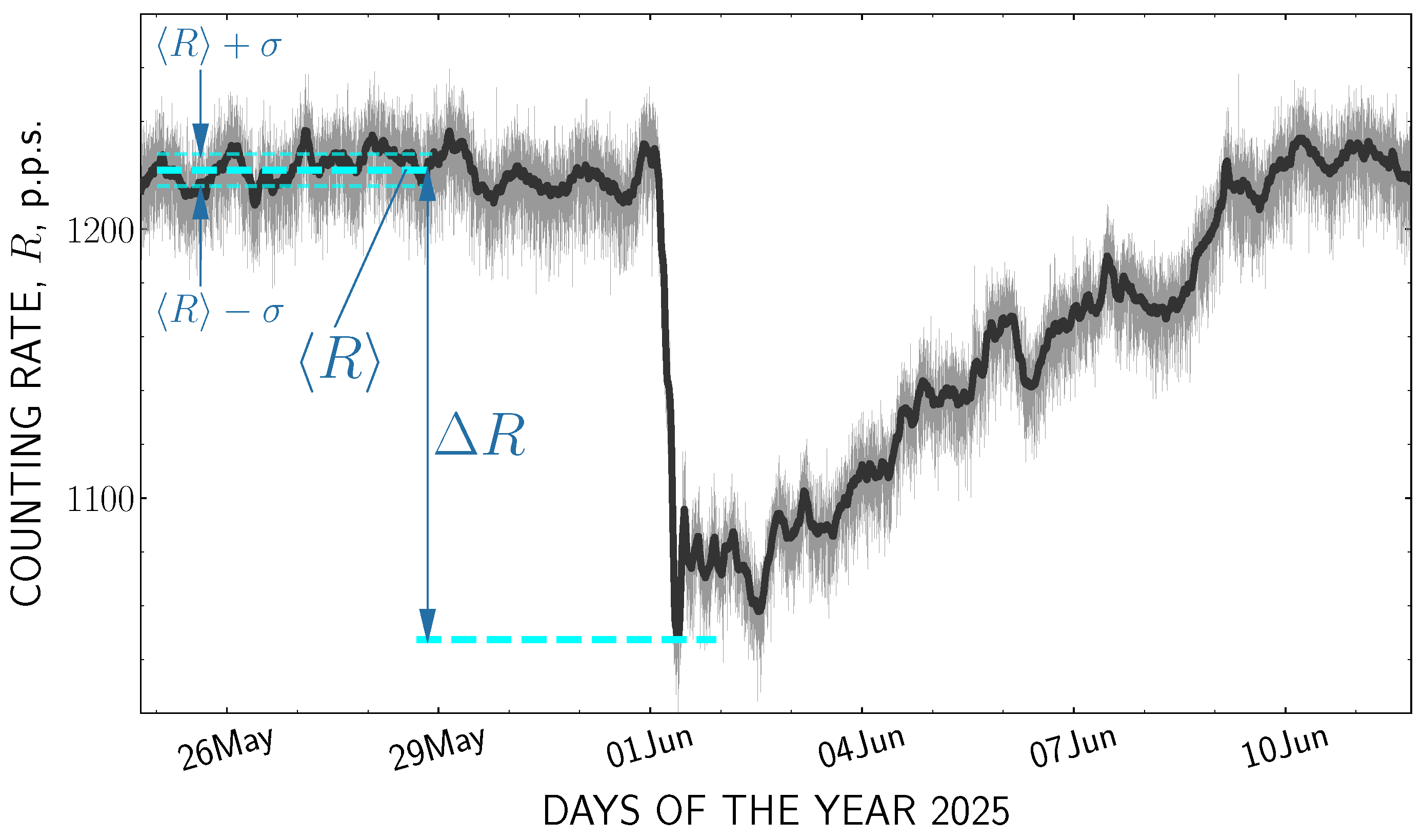

| the NM64 neutron supermonitor | 1222 | 6.0 | 175 | 0.14 | 29 |

| thermal neutron detectors #1, #2, and #3 | 19.4 20.2 14.8 | 0.21 0.24 0.17 | 2.9 2.9 2.1 | 0.15 0.14 0.14 | 14 12 12 |

| gamma detectors at 3340, 3750, and 3900 m a.s.l. | 30.7 45.2 45.8 | 0.57 0.48 1.2 | 2.2 3.6 5.3 | 0.07 0.08 0.11 | 3.8 7.6 4.4 |

| Neutron Multiplicity, M | Effective Hadron Energy, , GeV | Background Counting Rate, , p.p.s. | Standard Deviation, , p.p.s. | Magnitude of the Forbush Decrease, p.p.s. | Relative Magnitude, | Magnitude in Standard Deviations, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5–1 | 452 | 2.8 | 43 | 0.10 | 15 |

| 2 | 2 | 175 | 0.96 | 28 | 0.16 | 29 |

| 3 | 3 | 62.1 | 0.46 | 11 | 0.19 | 25 |

| 4, 5 | 6–10 | 33.8 | 0.29 | 6.7 | 0.20 | 23 |

| 6, 7 | 13–17 | 7.1 | 0.076 | 1.3 | 0.18 | 17 |

| 8, 9, 10 | 20–30 | 2.7 | 0.035 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shepetov, A.; Kryakunova, O.; Koichubayev, R.; Nikolayevskiy, N.; Ryabov, V.; Seifullina, B.; Tsepakina, I.; Zhukov, V. Observation of the Large Forbush Decrease Event on 1–10 June 2025 at the Tien Shan Cosmic Ray Station. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121349

Shepetov A, Kryakunova O, Koichubayev R, Nikolayevskiy N, Ryabov V, Seifullina B, Tsepakina I, Zhukov V. Observation of the Large Forbush Decrease Event on 1–10 June 2025 at the Tien Shan Cosmic Ray Station. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121349

Chicago/Turabian StyleShepetov, Alexander, Olga Kryakunova, Rustam Koichubayev, Nikolay Nikolayevskiy, Vladimir Ryabov, Botakoz Seifullina, Irina Tsepakina, and Valery Zhukov. 2025. "Observation of the Large Forbush Decrease Event on 1–10 June 2025 at the Tien Shan Cosmic Ray Station" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121349

APA StyleShepetov, A., Kryakunova, O., Koichubayev, R., Nikolayevskiy, N., Ryabov, V., Seifullina, B., Tsepakina, I., & Zhukov, V. (2025). Observation of the Large Forbush Decrease Event on 1–10 June 2025 at the Tien Shan Cosmic Ray Station. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1349. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121349