A Smoke Chamber Study on Some Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Size-Segregated Aerosol and Microclimatic Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

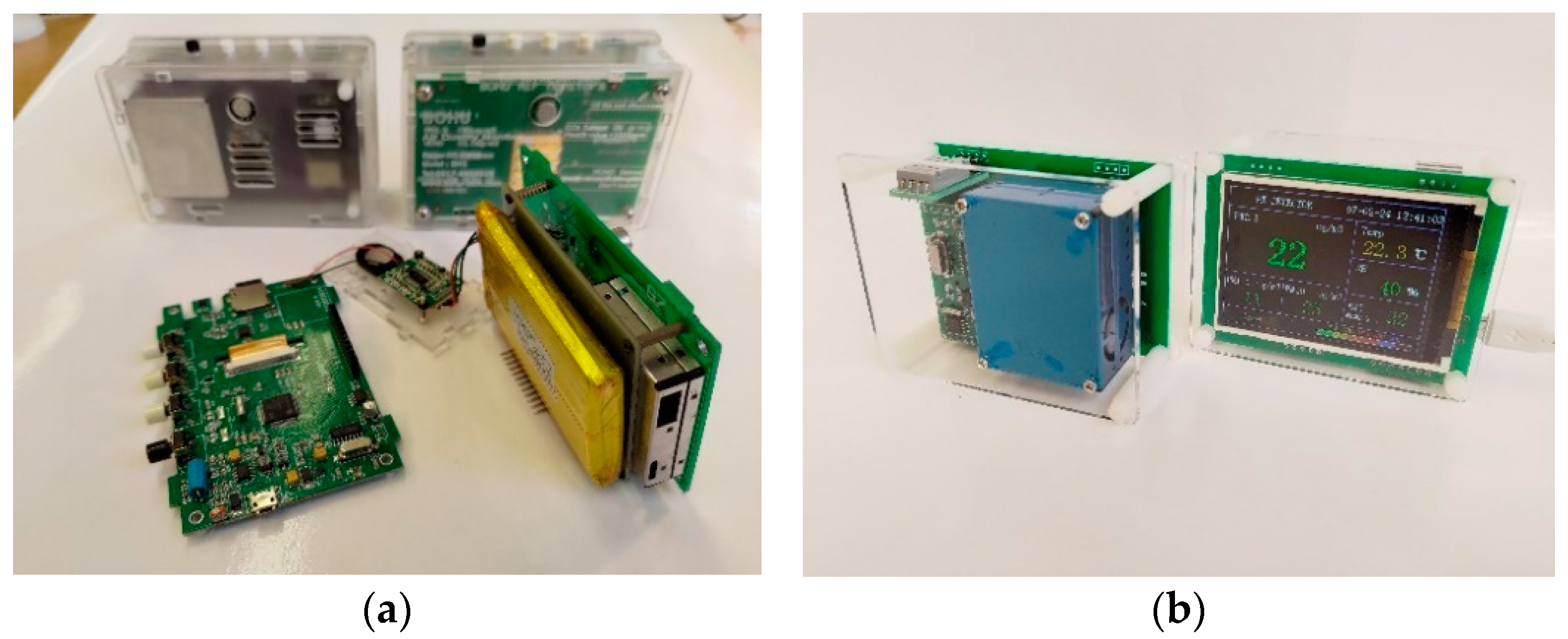

2.1. Instrumentation

2.2. Measurement Procedures

2.3. Data Evaluation and Statistical Methods

3. Results

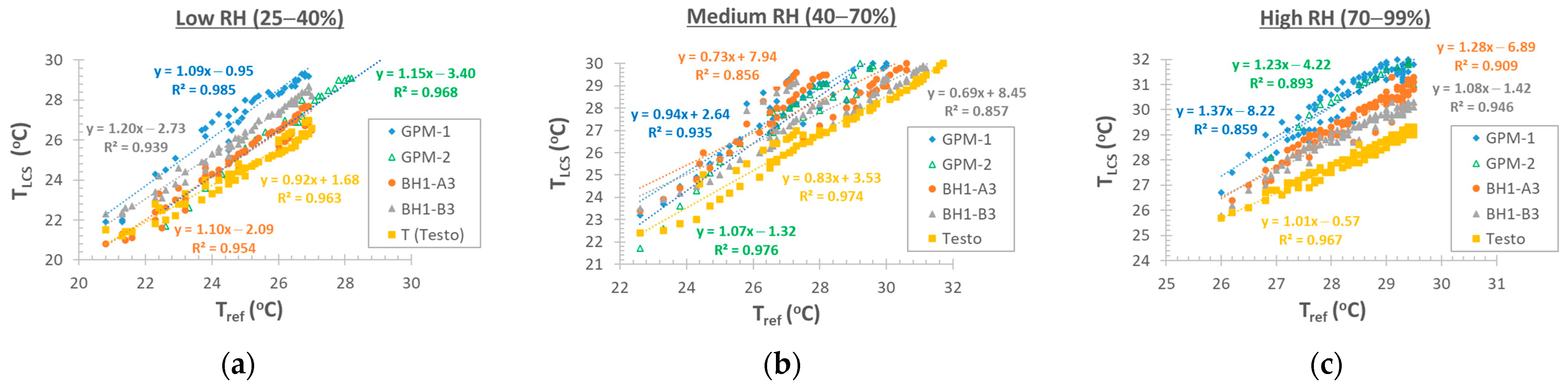

3.1. Ambient Microclimatic Measurements in the Smoke Chamber

3.1.1. Air Temperature

3.1.2. Relative Humidity

3.2. Monitoring Size-Segregated Aerosol in the Smoke Chamber

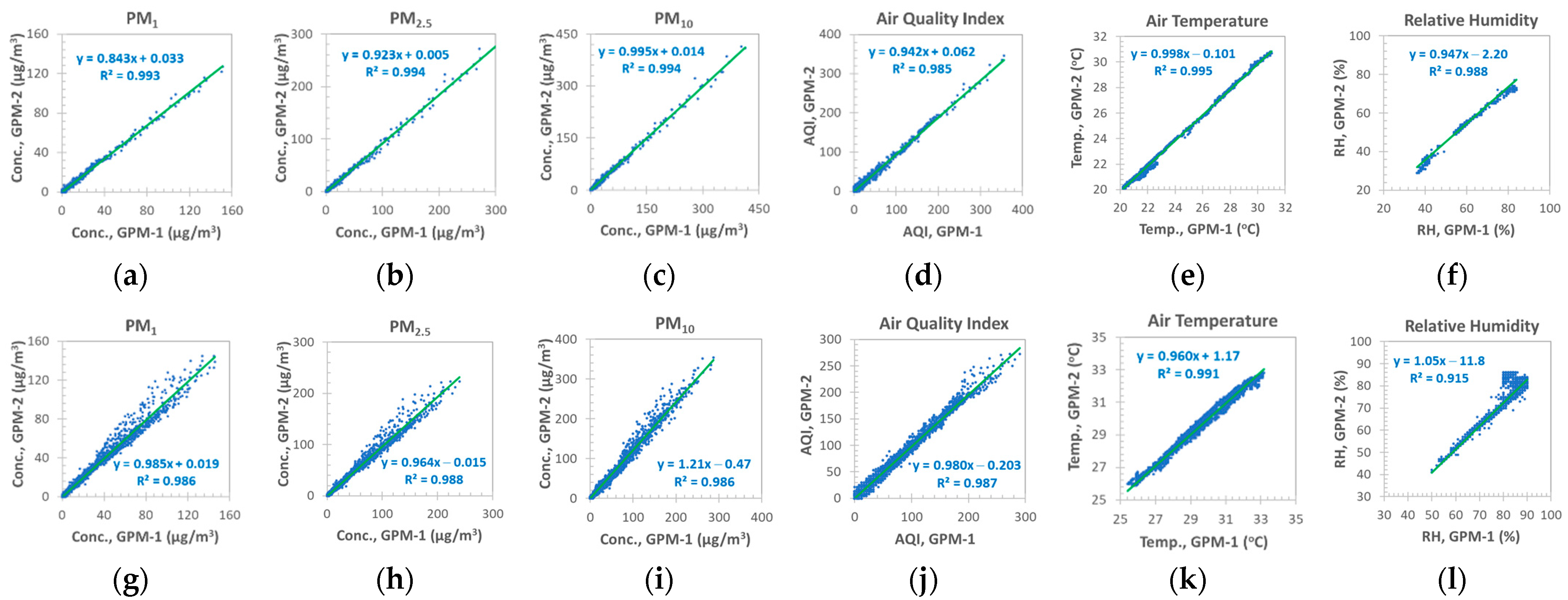

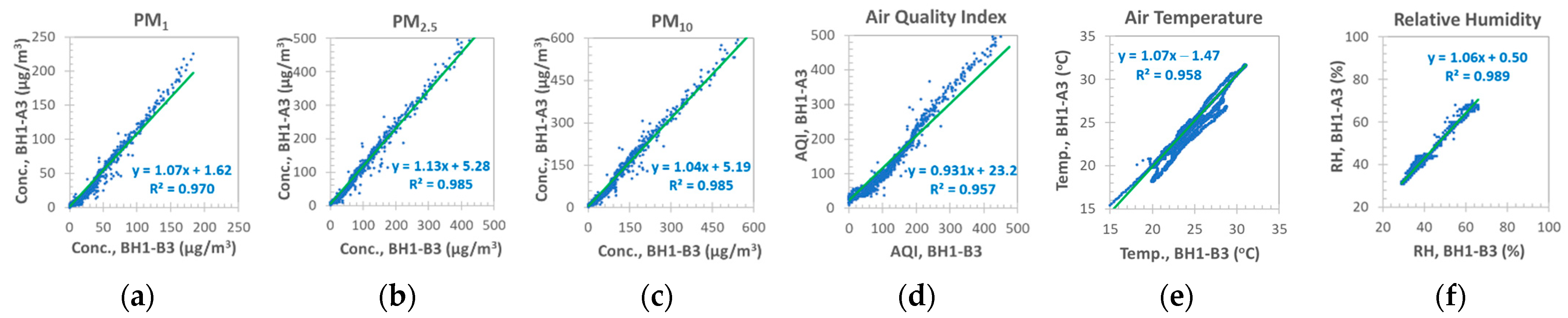

3.2.1. Comparison of LCSs of the Same Design

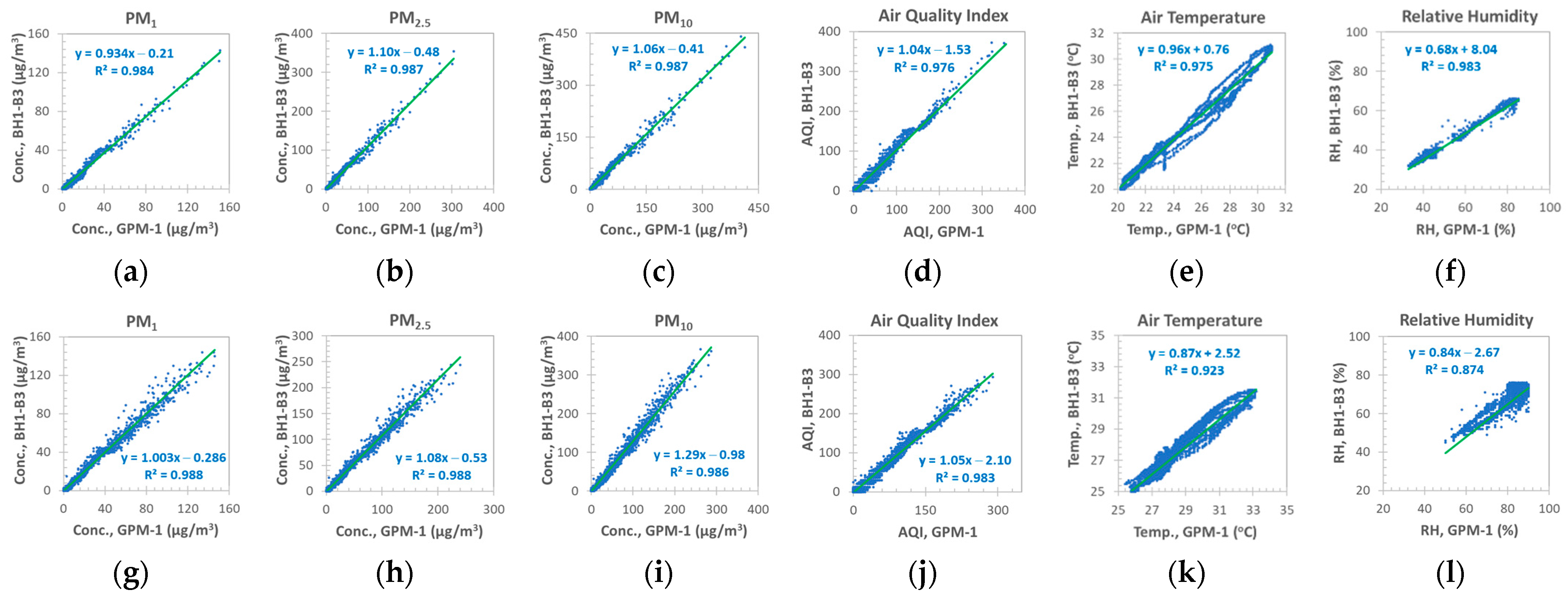

GPM Sensors

BH1 Sensors

3.2.2. Comparison of Sensors of Different Types

GPM versus BH1 Sensors

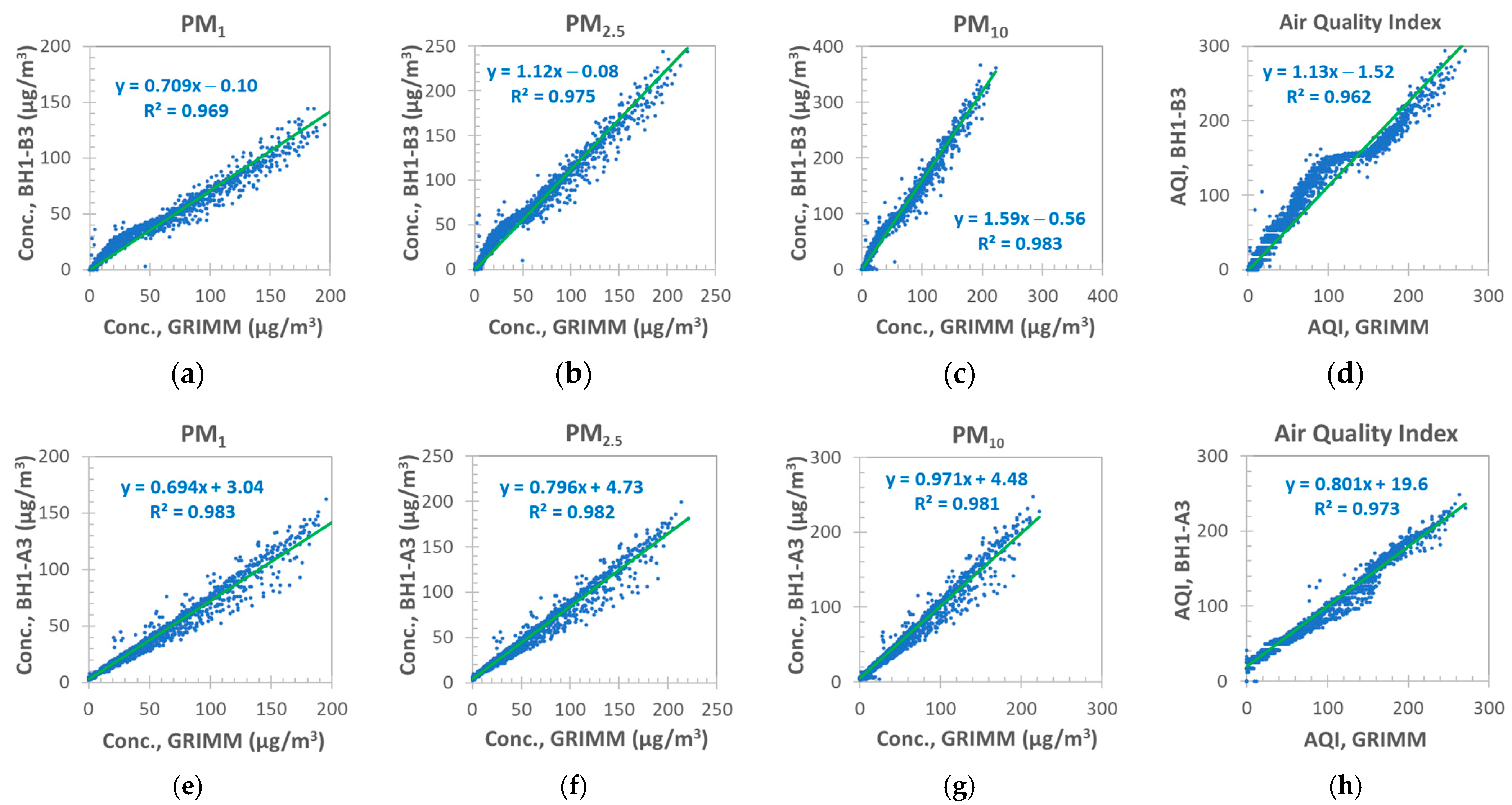

GPM versus GRIMM Monitor

BH1 versus GRIMM Monitor

3.3. Analytical Performance of the Sensors

3.3.1. Error of the LCSs for Ambient Microclimatic Parameters

3.3.2. Performance of LCSs for Size-Segregated Aerosol

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dockery, D.W.; Speizer, F.E.; Stram, D.O.; Ware, J.H.; Spengler, J.D.; Ferris, B.G., Jr. Effects of inhalable particles on respiratory health of children. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989, 139, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for Cultural Heritage: Measurement, Risk Assessment, Conservation, Restoration, and Maintenance of Indoor and Outdoor Monuments, 3rd ed.; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spolnik, Z.; Bencs, L.; Worobiec, A.; Kontozova, V.; Van Grieken, R. Application of EDXRF and thin window EPMA for the investigation of the influence of hot air heating on the generation and deposition of particulate matter. Microchim. Acta 2005, 149, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaf, W.; Bencs, L.; Van Grieken, R.; De Wael, K.; Janssens, K. Indoor particulate matter in four Belgian heritage sites: Case studies on the deposition of dark-colored and hygroscopic particles. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 506–507, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Sixth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, K.E.; Whitaker, J.; Petty, A.; Widmer, C.; Dybwad, A.; Sleeth, D.; Martin, R.; Butterfield, A. Ambient and laboratory evaluation of a low-cost particulate matter sensor. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 221, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, M.L.; Xiong, F.Z.L.; Gentner, D.; Kerkez, B.; Kohrman-Glaser, J.; Koehler, K. Field and Laboratory Evaluations of the Low-Cost Plantower Particulate Matter Sensor. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayahi, T.; Butterfield, A.; Kelly, K.E. Long-term field evaluation of the Plantower PMS low-cost particulate matter sensors. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayahi, T.; Kaufman, D.; Becnel, T.; Kaur, K.; Butterfield, A.E.; Collingwood, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gaillardon, P.E.; Kelly, K.E. Development of a calibration chamber to evaluate the performance of low-cost particulate matter sensors. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zusman, M.; Schumacher, C.S.; Gassett, A.J.; Spalt, E.W.; Austin, E.; Larson, T.V.; Carvlin, G.; Seto, E.; Kaufman, J.D.; Sheppard, L. Calibration of low-cost particulate matter sensors: Model development for a multi-city epidemiological study. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, S.; Min, K.T.; Moore, J.; Lundrigan, P.; Patwari, N.; Collingwood, S.; Balch, A.; Kelly, K.E. Indoor Household Particulate Matter Measurements Using a Network of Low-cost Sensors. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, A.; Handy, R.G.; Sleeth, D.K.; Schaefer, C.; Zhang, Y.; Pahler, L.F.; Ramsay, J.; Collingwook, S.C. Aerosol Measurement Degradation in Low-Cost Particle Sensors Using Laboratory Calibration and Field Validation. Toxics 2023, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Kelly, K.E. Laboratory evaluation of the Alphasense OPC-N3, and the Plantower PMS5003 and PMS6003 sensors. J. Aerosol Sci. 2023, 171, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuula, J.; Mäkelä, T.; Aurela, M.; Teinilä, K.; Varjonen, S.; González, O.; Timonen, H. Laboratory evaluation of particle-size selectivity of optical low-cost particulate matter sensors. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 2413–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, M.; Schneider, P.; Castell, N.; Hamer, P. Assessment of Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensor Systems against Optical and Gravimetric Methods in a Field Co-Location in Norway. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.W.; Le, T.C.; Tu, J.W.; Wang, C.E.; Chang, S.C.; Yu, Y.; Lin, G.Y.; Aggarwal, S.G.; Tsai, C.J. Long-term evaluation and calibration of three types of low-cost PM2.5 sensors at different air quality monitoring stations. J. Aerosol Sci. 2021, 157, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencs, L.; Plósz, B.; Mmari, A.G.; Szoboszlai, N. Comparative Study on the Use of Some Low-Cost Optical Particulate Sensors for Rapid Assessment of Local Air Quality Changes. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, M.; Sowka, I.; Szymanski, P.; Batog, P. Assessing the usefulness of dense sensor network for PM2.5 monitoring on an academic campus area. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.X.; Zhu, X.L.; Chen, C.; Ge, Y.H.; Wang, W.D.; Zhao, Z.H.; Cai, J.; Kan, H.D. On-field test and data calibration of a low-cost sensor for fine particles exposure assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 211, 111958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; He, J.Y.; Austin, E.; Seto, E.; Novosselov, I. Assessing the value of complex refractive index and particle density for calibration of low-cost particle matter sensor for size-resolved particle count and PM2.5 measurements. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, N.; Chapman, L.; Bloss, W.; Pope, F. Field Calibration and Evaluation of an Internet-of-Things-Based Particulate Matter Sensor. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 798485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimette, J.R.; Malm, W.C.; Schichtel, B.A.; Shridan, P.J.; Andrews, E.; Ogren, J.A.; Arnott, W.P. Evaluating the PurpleAir monitor as an aerosol light scattering instrument. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2022, 15, 655–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Bi, J.Z.; Ott, W.R.; Sarnat, J.; Liu, Y. Calibration of low-cost PurpleAir outdoor monitors using an improved method of calculating PM2.5. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 256, 118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L. Intercomparison of PurpleAir Sensor Performance over Three Years Indoors and Outdoors at a Home: Bias, Precision, and Limit of Detection Using an Improved Algorithm for Calculating PM2.5. Sensors 2022, 22, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Lee, S.H.; Yeo, M.S.; Rim, D.H. Field and laboratory evaluation of PurpleAir low-cost aerosol sensors in monitoring indoor airborne particles. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryner, J.; L’Organge, C.; Mahaffy, J.; Miller-Lionberg, D.; Hofstetter, C.; Wilson, A.; Volckens, J. Laboratory evaluation of low-cost PurpleAir PM monitors and in-field correction using co-located portable filter samplers. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 220, 117067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaratne, R.; Liu, X.T.; Thai, P.; Dunbabin, M.; Morawska, L. The influence of humidity on the performance of a low-cost air particle mass sensor and the effect of atmospheric fog. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 4883–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlborg, D.; Björling, M.; Mattsson, M. Evaluation of field calibration methods and performance of AQMesh, a low-cost air quality monitor. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castell, N.; Dauge, F.R.; Schneider, P.; Vogt, M.; Lerner, U.; Fishbain, B.; Broday, D.; Bartonova, A. Can commercial low-cost sensor platforms contribute to air quality monitoring and exposure estimates? Environ. Int. 2017, 99, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, A.; Walsh, P.T. Comparison of Portable, Real-Time Dust Monitors Sampling Actively, with Size-Selective Adaptors, and Passively. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2007, 51, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salimifard, P.; Rim, D.; Freihaut, J.D. Evaluation of low-cost optical particle counters of monitoring individual indoor aerosol sources. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, S.; Apsley, A.; MacCalman, L. An inexpensive particle monitor for smoker behaviour modification in homes. Tob. Control 2013, 11, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowich, K.M.; Chiliński, M.T. Evaluation of two low-cost optical particle counters for the measurement of ambient aerosol scattering coefficient and Ångström exponent. Sensors 2020, 20, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Jing, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J.K.; Biswas, P. Laboratory evaluation and calibration of three low-cost particle sensors for particulate matter measurement. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilley, L.R.; Shaw, M.; Pound, R.; Kramer, L.J.; Price, R.; Young, S.; Lewis, A.C.; Pope, F.D. Evaluation of a low-cost optical particle counter (Alphasense OPC-N2) for ambient air monitoring. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnosija, N.; Zamora, M.L.; Rule, A.M.; Payne-Sturges, D. Laboratory Chamber Evaluation of Flow Air Quality Sensor PM2.5 and PM10 Measurements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoh, N.A.; Xu, G.; Kumar, A.R.; Wang, Y. Calibration of low-cost particulate matter sensors for coal dust monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaratne, R.; Liu, X.T.; Ahn, K.-H.; Asumandu-Sakyi, A.; Fisher, G.; Gao, J.; Mabon, A.; Mazaheri, M.; Mullins, B.; Nyaku, M.; et al. Low-cost PM2.5 Sensors: An Assessment of their Suitability for Various Applications. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousan, S.; Regmi, S.; Park, Y.M. Laboratory Evaluation of Low-Cost Optical Particle Counters for Environmental and Occupational Exposures. Sensors 2021, 21, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, M.X.; Xiong, Y.; Du, S.; Du, K. Evaluation and calibration of a low-cost particle sensor in ambient conditions using machine-learning methods. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2020, 13, 1693–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, R.A.G.; Hernández, L.E.M.; Schalm, O.; Rodríguez, E.H.; Sánchez, D.A.; Pérez, M.C.M.; Caraballo, V.N.; Jacobs, W.; Laguardia, A.M. A Low-Cost Calibration Method for Temperature, Relative Humidity, and Carbon Dioxide Sensors Used in Air Quality Monitoring Systems. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, B.; Barretta, L.; Del Giudice, A.; De Vito, S.; Di Francia, G.; Esposito, E.; Formisano, F.; Massera, E.; Miglietta, M.L.; Polichetti, T. A review of low-cost particulate matter sensors from the developers’ perspectives. Sensors 2020, 20, 6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.R.; Malings, C.; Pandis, S.N.; Presto, A.A.; McNeill, V.F.; Westervelt, D.M.; Beekmann, M.; Subramanian, R. From low-cost sensors to high-quality data: A summary of challenges and best practices for effectively calibrating low-cost particulate matter sensors. J. Aerosol Sci. 2021, 158, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.C.; Kumar, P.; Pilla, F.; Skouloudis, A.N.; Di Sabatino, S.; Ratti, C.; Yasar, A.; Rickerby, D. End-user perspective of low-cost sensors for outdoor air pollution monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuval; Molho, H.M.; Zivan, O.; Broday, D.M.; Raz, R. Application of a sensor network of low cost optical particle counters for assessing the impact of quarry emissions on its vicinity. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 211, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency); Duvall, R.M.; Clements, A.L.; Hagler, G.; Kamal, A.; Kilaru, V.; Goodman, L.; Frederick, S.; Barkjohn, K.K.; VonWald, I.; et al. Performance Testing Protocols, Metrics, and Target Values for Fine Particulate Matter Air Sensors. EPA/600/R-20/280. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- IUPAC; Inczédy, J.; Lengyel, T.; Ure, A.M.; Gelencsér, A.; Hulanicki, A. (Eds.) Compendium of Analytical Nomenclature, 3rd ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 21 May 2008 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2008:152:TOC (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Won, W.S.; Oh, R.; Lee, W.; Ku, S.K.; Su, P.C.; Yoon, Y.J. Hygroscopic properties of particulate matter and effects of their interactions with weather on visibility. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Wildani, A.; Chang, H.H.; Liu, Y. Incorporating low-cost sensor measurements into high-resolution PM2.5 modeling at a large spatial scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.E.; Xing, W.W.; Sayahi, T.; Mitchell, L.; Becnel, T.; Gaillardon, P.-E.; Meyer, M.; Whitaker, R.T. Community-based measurements reveal unseen differences during air pollution episodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensor Type/No. | Low RH | Medium RH | High RH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MNE | MNB | RMSE | MNE | MNB | RMSE | MNE | MNB | |

| GPM-1 | 1.9 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 7.7 | 5.4 | 2.2 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| GPM-2 | 0.8 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 7.2 | 7.2 |

| BH1-A3 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 |

| BH1-B3 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 6.2 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Sensor Type/No. | Low RH | Medium RH | High RH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MNE | MNB | RMSE | MNE | MNB | RMSE | MNE | MNB | |

| GPM-1 | 5.1 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 9.7 | 9.5 | −9.4 |

| GPM-2 | 1.2 | 3.2 | −2.5 | 7.5 | 9.0 | −8.5 | 13.2 | 13.6 | −13.6 |

| BH1-A3 | 5.4 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 7.7 | 8.9 | −8.3 | 16.0 | 16.6 | −16.6 |

| BH1-B3 | 2.3 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 9.7 | 12.5 | −12.5 | 21.6 | 22.8 | −22.8 |

| Sensor/Error Types * | Bias for Low/Medium RH (High RH) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM1 | PM2.5 | PM10 | Ta | RH | |

| GPM-1–GPM-2 | |||||

| RMSE | 3.8 (5.6) | 6.4 (8.1) | 15 (26) | 0.2 (0.3) | 7.5 (8.1) |

| MNE (%) | 7.0 (8.6) | 9.1 (8.7) | 12 (17) | 0.5 (0.8) | 11.7 (9.1) |

| MNB (%) | −4.3 (4.6) | −6.4 (0.9) | 9.0 (19) | −0.4 (0.1) | −10.5 (−7.7) |

| GPM-1–BH1-A3 | |||||

| RMSE | 7.1 (7.8) | 11 (18) | 14 (21) | 1.2 (1.7) | 2.3 (4.3) |

| MNE (%) | 21 (22) | 33 (41) | 36 (46) | 4.5 (2.8) | 15 (14) |

| MNB (%) | −7.7 (−12.4) | −23 (−27) | −24 (−29) | −4.3 (−2.7) | −12.8 (−12) |

| GPM-2–BH1-A3 | |||||

| RMSE | 9.4 (11) | 7.7 (21) | 24 (44) | 1.2 (1.7) | 2.3 (5.0) |

| MNE (%) | 21 (29) | 25 (43) | 46 (73) | 4.1 (2.9) | 3.0 (5.2) |

| MNB (%) | −3.0 (−15) | −17 (−27) | −30 (−40) | −3.9 (−2.8) | −2.6 (−4.6) |

| GPM-2–BH1-B3 | |||||

| RMSE | 14 (12) | 11 (20) | 23 (43) | 2.2 (2.8) | 13 (16) |

| MNE (%) | 40 (46) | 42 (59) | 66 (94) | 6.7 (8.8) | 25 (26) |

| MNB (%) | −7.8 (20) | −21 (−32) | −35 (−44) | 7.3 (−5.2) | −20 (−20) |

| BH1-A3–BH1-B3 | |||||

| RMSE | 5.4 (6.8) | 6.6 (8.4) | 7.3 (10) | 3.1 (2.6) | 11.1 (13) |

| MNE (%) | 18 (19) | 16 (17) | 17 (19 | 10 (8.6) | 22 (21) |

| MNB (%) | −6.9 (−6.8) | −6.2 (−6.3) | −7.6 (−7.8) | 11.6 (8.1) | −18 (−16) |

| Sensor/Error Type | Parameter/Bias Value * | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PM1 | PM2.5 | PM10 | |

| GPM-1 | |||

| RMSE | 18 (22) | 10 (11) | 19 (22) |

| MNE (%) | 24 (22) | 42 (37) | 64 (57) |

| MNB (%) | −2.8 (−8.5) | 41 (33) | 64 (56) |

| GPM-2 | |||

| RMSE | 21 (21) | 9.5 (10.8) | 30 (40) |

| MNE (%) | 24 (22) | 36 (37) | 75 (83) |

| MNB (%) | −6.9 (−5.0) | 31 (33) | 75 (83) |

| BOHU BH1-A3 | |||

| RMSE | 14 (22) | 7.5 (16) | 8.0 (9.3) |

| MNE (%) | 17 (25) | 13 (19) | 20 (17) |

| MNB (%) | −15 (−22) | 5.0 (−5.2) | 20 (8.0) |

| BOHU BH1-B3 | |||

| RMSE | 12 (21) | 6.8 (15) | 12 (10) |

| MNE (%) | 25 (30) | 9.2 (19) | 13 (16) |

| MNB (%) | −22 (−29) | −3.4 (−13) | 8.9 (−7.0) |

| Monitor Type | Aerosol Size-Range | LOD (µg/m3) | LOQ (µg/m3) | Peak Conc. (µg/m3) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPM | PM1 | 1.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (5.1) | 120 (145) |

| PM2.5 | 1.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (5.1) | 190 (240) | |

| PM10 | 1.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (5.1) | 280 (290) | |

| BOHU BH1-A3 | PM1 | 2.5 (3.5) | 9 (12) | 140 (160) |

| PM2.5 | 3.5 (4.5) | 12 (15) | 170 (200) | |

| PM10 | 3.5 (4.5) | 12 (15) | 210 (250) | |

| BOHU BH1-B3 | PM1 | 1.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (5.1) | 167 (162) |

| PM2.5 | 1.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (5.1) | 205 (198) | |

| PM10 | 1.5 (1.5) | 5.1 (5.1) | 256 (240) | |

| GRIMM | PM1 | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.85 (0.85) | 165 (205) |

| PM2.5 | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.85 (0.85) | 180 (220) | |

| PM10 | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.85 (0.85) | 185 (230) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bencs, L.; Nagy, A. A Smoke Chamber Study on Some Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Size-Segregated Aerosol and Microclimatic Parameters. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15030304

Bencs L, Nagy A. A Smoke Chamber Study on Some Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Size-Segregated Aerosol and Microclimatic Parameters. Atmosphere. 2024; 15(3):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15030304

Chicago/Turabian StyleBencs, László, and Attila Nagy. 2024. "A Smoke Chamber Study on Some Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Size-Segregated Aerosol and Microclimatic Parameters" Atmosphere 15, no. 3: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15030304

APA StyleBencs, L., & Nagy, A. (2024). A Smoke Chamber Study on Some Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring Size-Segregated Aerosol and Microclimatic Parameters. Atmosphere, 15(3), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15030304