Long-Term Changes in Ionospheric Climate in Terms of foF2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Long-Term Trends in foF2

3. Role of Non-CO2 Trend Drivers

4. Problems in Calculating Long-Term Trends in foF2

5. Conclusions

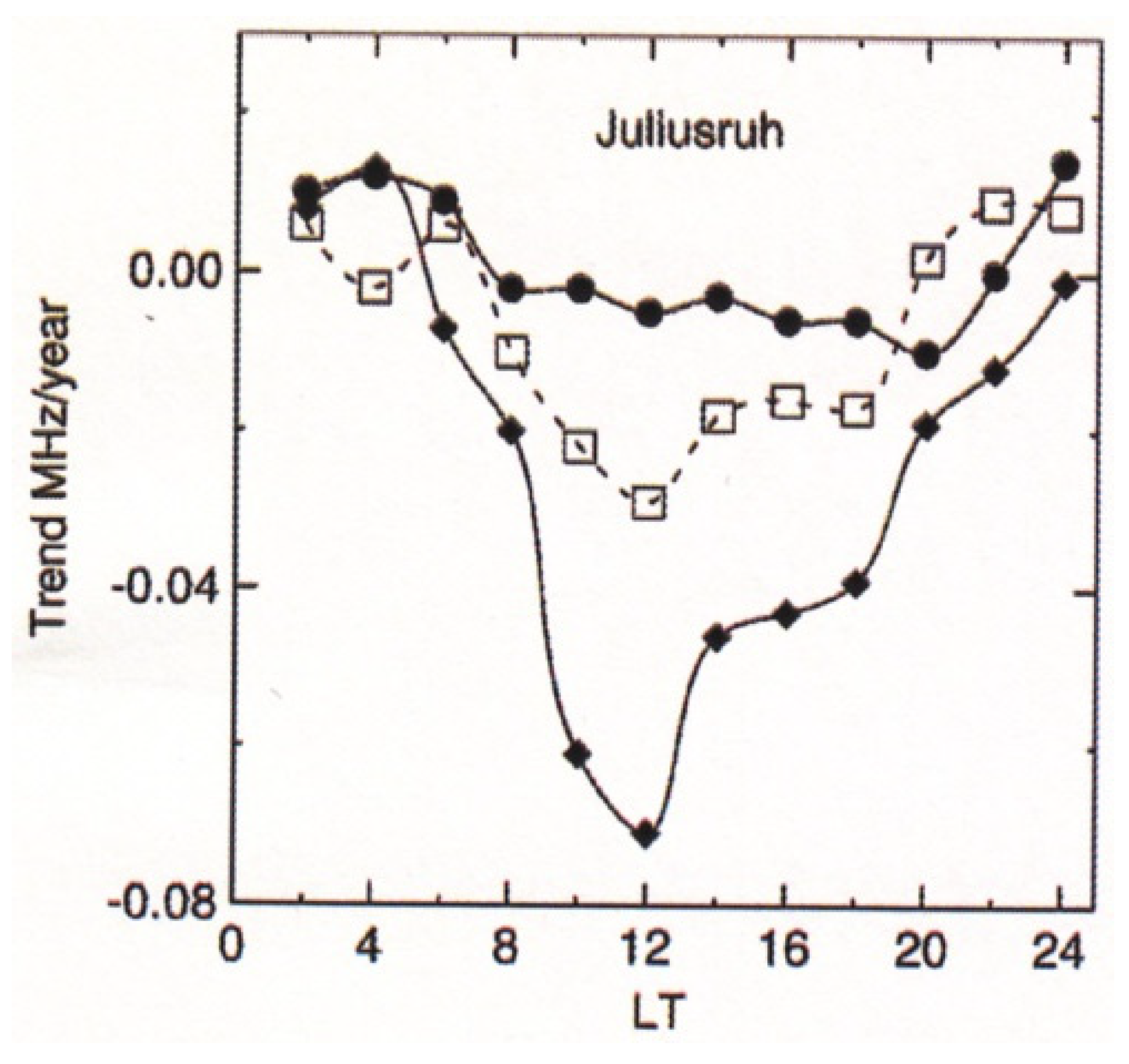

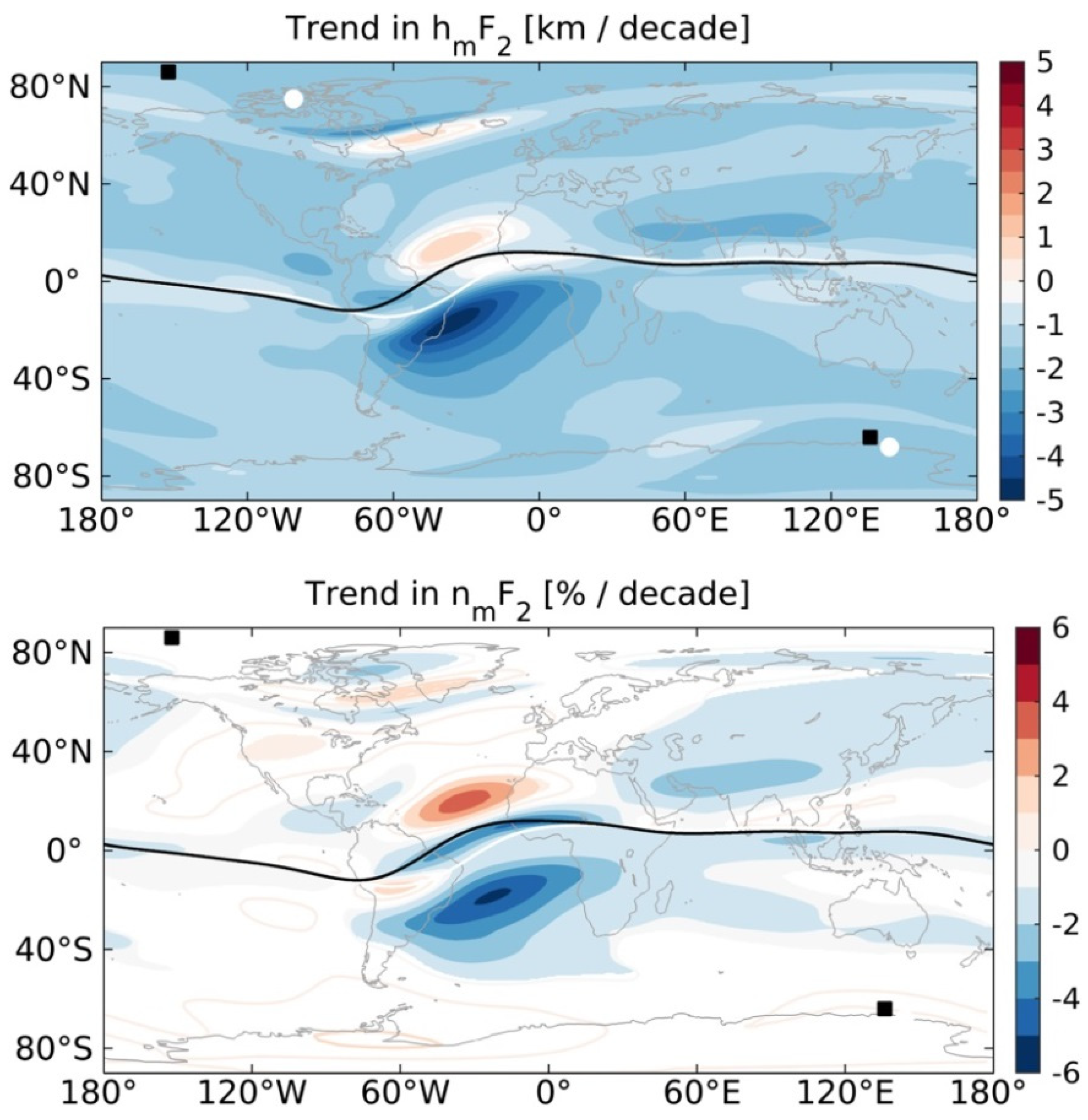

- Trends in foF2 are weak. They are mostly negative, but in some regions they are positive. Trends depend on the time of day and on the season; they are substantially stronger at midlatitudes in winter than in summer.

- There are more drivers of trends. Globally, the main driver of trends in foF2 is CO2, but in some regions, the impact of secular changes in the Earth’s main magnetic field is stronger, the latter being negative in some areas and positive in others.

- There are various sources of uncertainty in calculating trends in foF2. Data homogeneity is one of them. The removal of the impact of much stronger solar cycles on foF2 data with optimum solar activity proxies is another. The application of different methods might result in somewhat different strengths in trends, e.g., those calculated by linear regression versus those based on the EEMD method.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alfonsi, L.; DeFranceschi, G.; Perrone, L. Long term trends of the critical frequency of the F2 layer at northern and southern high latitude regions. Phys. Chem. Earth 2002, 27, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, J. Trends in the ionospheric E- and F-regions over Europe. Ann. Geophys. 1998, 16, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, J. Long-term trends in the ionospheric E and F1 regions. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 26, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, J.; Damboldt, T.; Mielich, J.; Suessmann, P. Comparing long-term trends in the ionospheric F2-region with two different methods. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2012, 77, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, H.; Vyas, G.D.; Sharma, S. Long-term changes in ionospheric parameters over Ahmedabad. Adv. Space Res. 1997, 20, 2161–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clilverd, M.A.; Ulich, T.; Jarvis, J.M. Residual solar cycle influence on trends in ionospheric F2-layer peak height. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2003, 108, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnossen, I. The importance of geomagnetic field changes versus rising CO2 levels for long-term change in the upper atmosphere. J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2014, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnossen, I.; Franzke, C. The role of the Sun in the long-term change in the F2-peak ionosphere: New insights from EEMD and numerical modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2014, 119, 8610–8623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D. Long-term trends in F2-layer parameters and their relation to other trends. Adv. Space Res. 2005, 35, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D. Long-term trends in the relation between daytime and nighttime values of foF2. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 26, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Danilov, A.D. Seasonal and diurnal variations in foF2 trends. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 3868–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D. Behavior of F2 region parameters and solar activity indices in the 24th cycle. Geom. Aeron. 2021, 61, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Danilov, A.D.; Konstantinova, A.V. Relationship between foF2 trends and geographic and geomagnetic coordinates. Geom. Aeron. 2014, 54, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D.; Konstantinova, A.V. Long-term changes in the relation between foF2 and hmF2. Geom. Aeron. 2016, 56, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D.; Konstantinova, A.V. Trends in parameters of the F2 layer and the 24th solar activity cycle. Geom. Aeron. 2020, 60, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.G. Trends in the F2 ionospheric layer due to long-term variations in the Earth’s magnetic field. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2009, 71, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J. The best solar activity proxy for long-term ionospheric investigations. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J.; Mikhailov, A.V.; Ulich, T.; Bremer, J.; Elias, A.G.; Ortiz de Adler, N.; Jara, V.; Abarca del Rio, R.; Foppiano, A.J.; Ovalle, E.; et al. Long-term trends in foF2: A comparison of various methods. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2006, 68, 1854–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J.; Yue, X.; Wan, W. Long-term trends in foF2: Their estimating and origin. Ann. Geophys. 2008, 26, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mielich, J.; Bremer, J. Long-term trends in the ionospheric F2-region with different solar activity indices. Ann. Geophys. 2013, 31, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, A.V. The geomagnetic control concept of the F2-layer parameter long-term trends. Phys. Chem. Earth 2002, 27, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, L.; Mikhailov, A.V. Geomagnetic control of the midlatitude foF1 and foF2 long-term variations: Recent observations in Europe. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2016, 121, 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Solomon, S.C.; Roble, R.G.; Kane, T.J. Model simulations of global change in the ionosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L07811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Burns, A.G.; Solomon, S.C.; Roble, R.G. The effect of carbon dioxide cooling on trends in the F2-layer ionosphere. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2009, 71, 1592–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulich, T.; Turunen, E. Evidence for long-term cooling of the upper atmosphere in ionosonde data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1997, 24, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, H.O.; Mahajan, E.E. Atmospheric greenhouse effect and ionospheric trends. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1998, 25, 3375–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-W.; Wu, J.; Igarashi, K.; Kato, H.; Wu, Z.-S. Long-term ionospheric trends based on ground-based ionosonde observations at Kokubunji, Japan. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, A09307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Wan, W.; Liu, L.; Ning, B.; Zhao, B. Applying artificial neural network to derive long-term foF2 trends in Asia/Pacific sector from ionosonde observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, D22307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastovicka, J.; Solomon, S.C.; Qian, L. Trends in the neural and ionized upper atmosphere. Space Sci. Rev. 2012, 168, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezac, L.; Yue, J.; Yongxiao, J.; Russell, J.M., III; Garcia, R.; López-Puertas, M.; Mlynczak, M.G. On long-term SABER CO2 trends and effects due to nonuniform space and time sampling. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2018, 123, 7958–7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnossen, I. Analysis and attribution of climate change in the upper atmosphere from 1950 to 2015 simulated by WACCM-X. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2020, 125, e2020JA028623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, C.; Hoffmann, P.; Liu, R.Q.; Merzlyakov, E.G.; Portnyagin, Y.I.; Manson, A.H.; Meek, C.E. Long-term trends, their changes, and interannual variability of Northern Hemisphere midlatitude MLT winds. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2012, 75–76, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J. A review of recent progress in trends in the upper atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sol.-Terr. Phys. 2017, 163, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D.; Konstantinova, A.V. Long-term variations of the parameters of the middle and upper atmosphere and ionosphere (review). Geom. Aeron. 2020, 60, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damboldt, T.; Suessmann, P. Consolidated Database of Worldwide Measured Monthly Medians of Ionospheric Characteristics foF2 and M(3000)FINAG Bulletin on Web, INAG-73, IAGA. 2012. Available online: https://www.ursi.org/files/CommissionWebsites/INAG/web-73/2012/damboldt_consolidated_database.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Liu, H.; Tao, C.; Jin, H.; Abe, T. Geomagnetic activity effect on CO2-driven trend in the thermosphere and ionosphere: Ideal model experiments with GAIA. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2021, 126, e2020JA028607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Hu, L.; Wei, F.; Wan, W.; Ning, B. Ionospheric trend over Wuhan during 1947–2018: Comparison between simulation and observation. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2018, 123, 1396–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D.; Konstantinova, A.V. Trends in the critical frequency foF2 after 2009. Geom. Aeron. 2016, 56, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, A.G.; de Haro Barbas, B.F.; Shibasaki, K.; Souza, J.R. Effect of solar cycle 23 in foF2 trend estimation. Earth Plan. Space 2014, 66, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; McInerney, J.M.; Solomon, S.S.; Liu, H.; Burns, A.G. Climate changes in the upper atmosphere: Contributions by the changing greenhouse gas concentrations and Earth’s magnetic field from the 1960s to 2010s. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2021, 126, e2020JA029067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J. On the role of ozone in the long-term trends in the upper atmosphere-ionosphere system. Ann. Geophys. 2012, 30, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.L.; Zhang, S.-R.; Goncharenko, L.P. Is thermospheric global cooling caused by gravity waves? J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2013, 118, 3898–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.L.; Holt, J.M.; Zhang, S.-R.; Goncharenko, L.P. Long-term trends in thermospheric neutral temperatures and density above Millstone Hill. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2014, 119, 7940–7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J. Comment on “Long-term trends in thermospheric neutral temperatures and density above Millstone Hill” by Oliver, W.L.; Holt, J.M.; Zhang, S.-R.; Goncharenko, L.P. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 2347–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laštovička, J.; Jelínek, Š. Problems in calculating long-term trends in the upper atmosphere. J. Atmos. Solar-Terr. Phys. 2019, 189, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettitt, A.N. A non-parametric approach to the change point detection. Appl. Stat. 1979, 28, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandersson, H. A homogeneity test applied to precipitation data. J. Climatol. 1986, 6, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, A.D.; Konstantinova, A.V. Behavior of the ionospheric F2 layer at the turn of the centuries. Critical frequency. Geom. Aeron. 2013, 53, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 1, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laštovička, J. Long-Term Changes in Ionospheric Climate in Terms of foF2. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13010110

Laštovička J. Long-Term Changes in Ionospheric Climate in Terms of foF2. Atmosphere. 2022; 13(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13010110

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaštovička, Jan. 2022. "Long-Term Changes in Ionospheric Climate in Terms of foF2" Atmosphere 13, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13010110

APA StyleLaštovička, J. (2022). Long-Term Changes in Ionospheric Climate in Terms of foF2. Atmosphere, 13(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos13010110