1. Introduction

El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is the main interannual variability phenomenon in the climate system that strongly impacts climate in many regions worldwide [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Until approximately the 1990s, most of El Niño events were characterized by maximum tropical sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies located over the eastern equatorial Pacific. For this reason, such Canonical El Niño events are also referred to as Eastern Pacific El Niño (EP, [

6]). However, other studies have shown that El Niño events with maximum tropical SST variability located over the central equatorial Pacific started to be more frequent since the 1990s [

7]. These events were baptized as “dateline El Niño” by Larkin and Harrison [

8], and as El Niño Modoki by Ashok et al. [

9], although nowadays most of the studies refer to this type of El Niño as Central Pacific El Niño [

10,

11].

Given that the position of the maximum SST anomalies is directly related to the diabatic heating released over the equatorial Pacific in upper levels, different SST anomaly patterns can induce different upper level divergent circulation anomalies that, in turn, can generate changes in the tropical-extratropical teleconnection patterns [

12,

13,

14,

15]. As consequence of this, in recent years there has been a flurry of activity to determine the teleconnection patterns associated with these two different types of El Niño.

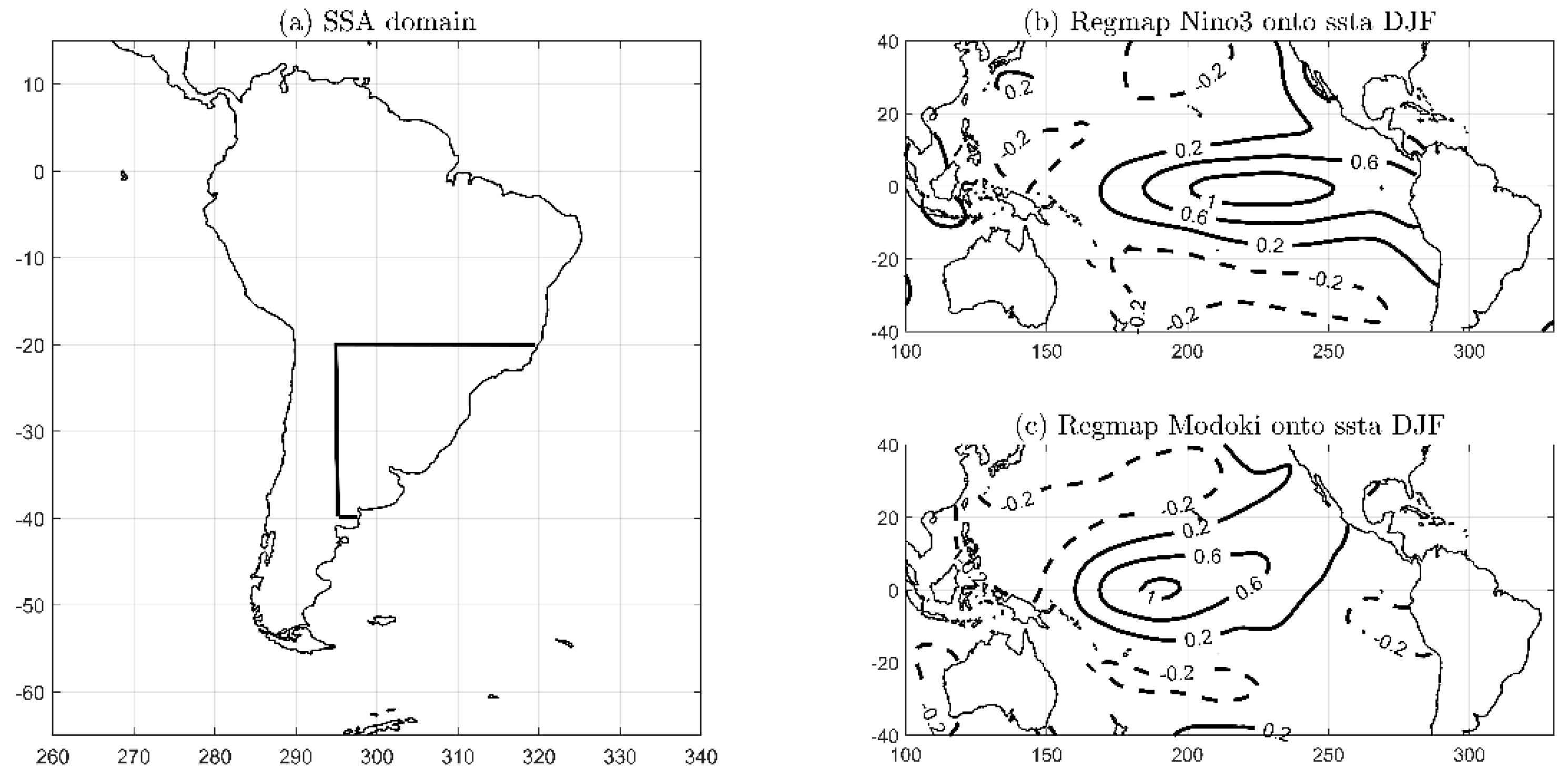

One of the regions most affected by El Niño is Subtropical South America (SSA, see

Figure 1a), a region located east of the Andes mountains between 20° S and 40° S and with watershed in the tropical Atlantic (

Figure 1a; e.g., [

10,

11,

15,

16,

17]). In this study, we focus on the impacts of the positive phase of these two different El Niño patterns on SSA rainfall during the austral summer season, here defined as December-January-February (DJF).

Focusing on Canonical El Niño events, many previous studies have shown that this pattern increases precipitation over SSA through (1) an increase in the advection of cyclonic vorticity in upper levels that favors the development of baroclinicity, and/or (2) the intensification of the moisture transport from the tropics toward SSA that enhances the availability of moisture for precipitation over the region [

12,

15,

16,

18]. These two factors, moisture availability at lower levels and dynamic lift, are the ingredients needed to develop rainfall anomalies. Andreoli et al. [

10] also show positive rainfall anomalies over SSA associated with the Canonical El Niño event, but the signal is only statistically significant over a small region within SSA that covers part of the Argentinian’s provinces of Mendoza and Córdoba. This discrepancy with the rest of the studies could be related to the period considered by Andreoli et al. [

10]: they focused on precipitation anomalies over the period 1901–2010 and it is known that the quality of the reanalysis before 1979 in the Southern Hemisphere (SH) is poor because of the lack of observed data.

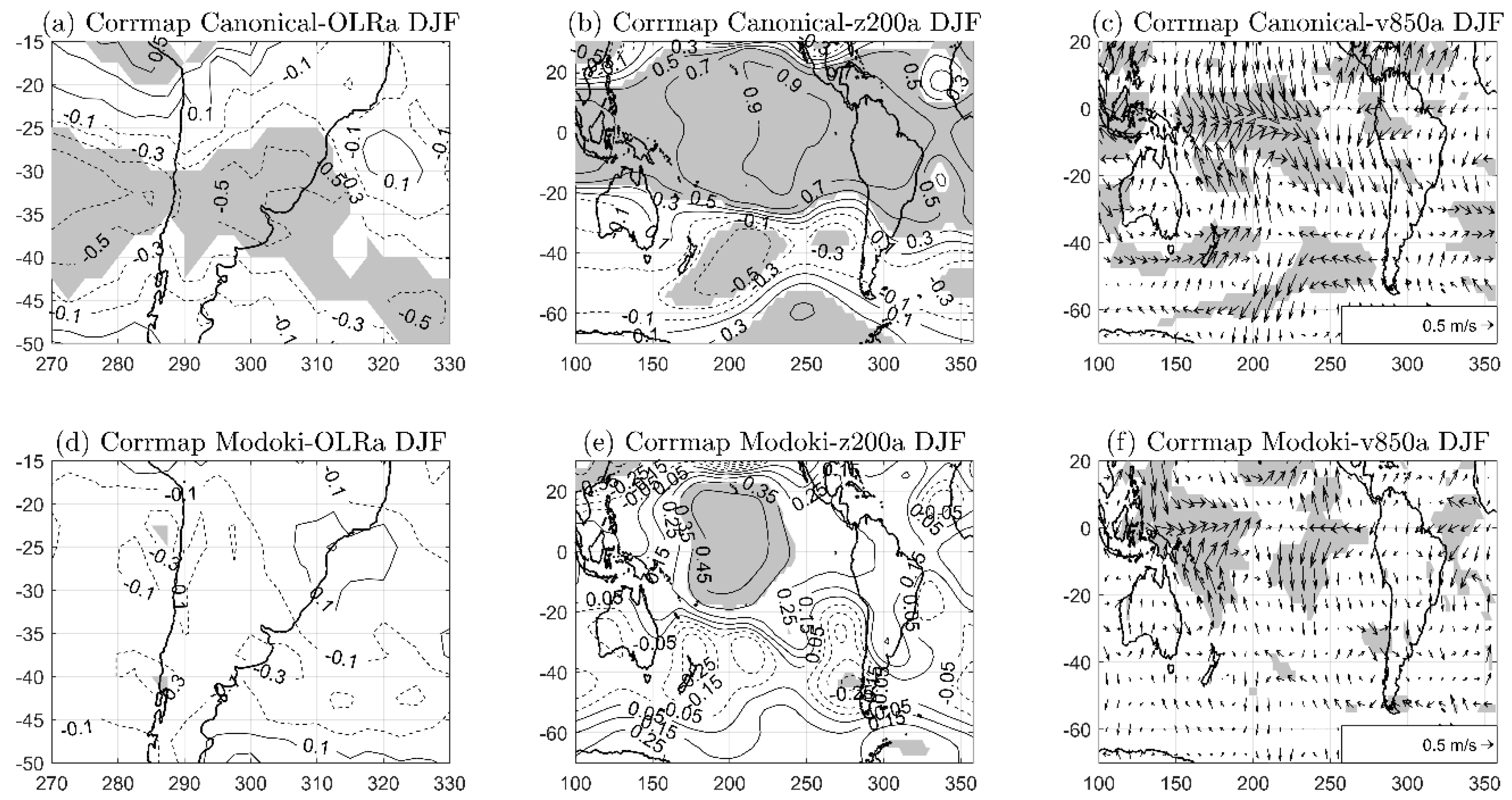

Focusing on El Niño Modoki events, their influence on SSA rainfall anomalies is not yet clear. Some studies have shown a negative and statistically significant precipitation signal over SSA during an El Niño Modoki (see Figure 4 from Weng et al. [

13]). Results from Tedeschi et al. [

15] and Brito [

19] also point in this direction although the negative precipitation signal over SSA is not found to be statistically significant. However, there are other studies suggesting the opposite, an increase of SSA precipitation during El Niño Modoki [

18]. Andreoli et al. [

10] also show positive rainfall anomalies over SSA, but the signal is statistically significant only in some small regions. Differences among studies can arise from the dataset employed, the period considered and the methodology used to define the El Niño Modoki index.

Studies have also shown that the upper level circulation anomalies associated with El Niño Modoki present a different spatial structure from those related to Canonical El Niño, with the former not showing a clear Rossby wave pattern propagating over the extratropical latitudes in the SH during the austral summer season [

10,

11,

13,

14]. Weng et al., [

13] is an exception, as their results (see their Figure 8) suggest that, associated with El Niño Modoki, there could be a weak Rossby wave pattern that emanates from the western Subtropical Pacific and propagates to the east, but it does not reach the South Atlantic Ocean. Some differences may result from the fact that Weng et al. [

13] analyze the January-February-March season, while the other previously mentioned studies focus on DJF. Nevertheless, all studies agree in the weaker intensity of the upper level circulation anomalies associated with El Niño Modoki in comparison with those related to the Canonical El Niño. However, the absence of a clear Rossby wave pattern associated with El Niño Modoki could be related to: (1) the smaller intensity of SST anomalies that characterize such events in comparison with the Canonical ones, and (2) a possible lower sensitivity of the atmosphere to the pattern of SST anomalies.

It is also worth mentioning that although there is, overall, agreement in the literature about the induced rainfall anomalies over SSA in the case of the Canonical El Niño events, the upper level circulation pattern observed over the SH is not exactly the same in all of them. For example, results from Sun et al. [

14], based on a partial correlation analysis, suggest that the upper level circulation anomalies related to Canonical El Niño events are characterized by a large Rossby wave train that emanates from eastern New Zealand (NZ) and propagates southeastward in an arc-like trajectory reaching the South Atlantic ocean (see their Figure 4a). This large Rossby wave train structure can also be discerned in Tedeschi et al. [

15] (see their Figure 10c). Additionally, a shorter Rossby wave seems to be emanating from the central-east subtropical south Pacific, although it does not seem to present an eastward propagation (Figure 4a from Sun et al. [

14]). On the other hand, Figure 10c from Tedeschi et al. [

15] suggests the existence of a short wave emanating from (30° S, 260° E) which could be propagating toward the northeast, generating an anomalous anticyclonic circulation over the northeastern SSA. The main difference between both studies is the strength of the events analyzed. While Sun et al. [

14] evaluate all the Canonical El Niño events (stronger and weaker), Tedeschi et al. [

15] focus mainly on the stronger ones. This could suggest that the shorter Rossby wave train may effectively propagate eastwards only in the strongest Canonical El Niño events.

An understanding of the conditions for the generation of the shorter Rossby wave is important for SSA rainfall, because this wave train has been shown to play a major role in increasing precipitation in the region [

17]. Barreiro [

17] explored the interannual variability of the extratropical transient activity in the SH and its influence on the austral summer precipitation over Uruguay. The author found that El Niño influences southern Uruguay when there is a southward displacement of the transient activity, which occurs when the two stationary waves are forced from the equatorial Pacific. The two stationary Rossby wave trains result in a large one that emanates from the central subtropical Pacific and propagates toward the south Atlantic Ocean in an arc-like trajectory, and a shorter one that emanates from the subtropical eastern south Pacific and propagates northeastward. Only when this short wave is strong, surface northerlies reach southern Uruguay and favor the increase of precipitation in the region [

17]. This seems to occur when the SST anomalies associated with El Niño are located in the region of Niño3.4, an index that cannot separate between Central and Eastern El Niño events (see their Figures 11a and 9d).

Finally, Weng et al. [

13] show the existence of two Rossby wave trains associated with Canonical El Niño, one of them emanating from the subtropical central Pacific and the other from the western South Pacific (their Figure 8a). Differently to what was reported by Sun et al. [

13] and Tedeschi et al. [

15], both of these wave trains propagate southeastward converging around (60° S, 120° E), where they propagate eastward. Such contrasting results might be a consequence of considering January-February-March season, instead of DJF.

Therefore, most studies show one or two Rossby wave trains as a response to Canonical El Niño events, but the presence or not of the shorter wave is not clear yet. In the case of El Niño Modoki, most studies do not show a clear wave train. This weaker response could be related to the fact that the SST anomalies associated with El Niño Modoki events are weaker than in the case of Canonical El Niño, or to the SST pattern itself.

The aim of this study was to understand whether the different response over SSA to El Niño depends on its intensity or/and on its spatial pattern. Special attention was paid to the number and characteristics of the quasi-stationary Rossby wave trains developed in response to the El Niño over the SH. Our approach is based on performing sensitivity experiments with an Atmosphere General Circulation Model (AGCM) in order to analyze the SH sensitivity to different El Niño patterns and intensities.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In

Section 2, we explain the data and methodology used. Then, in

Section 3, we focus on the analysis of the SH circulation response to the Canonical El Niño and El Niño Modoki patterns using reanalysis data. After that, in

Section 4, we investigate the SH circulation sensitivity to different ENSO’s patterns and intensities considering idealized sensitivity experiments. Finally, in

Section 5 we present the main conclusions of the work.

2. Data and Methods

To analyze the SH circulation response to different ENSO patterns and intensities and their impacts over SSA (see

Figure 1a), we focused on the austral summer season during the period 1979–2016 and considered both reanalysis data and the output from an AGCM. Reanalysis data was first considered to analyze the atmospheric response to different ENSO patterns and then to check whether the model could reproduce the atmospheric response to both El Niño patterns. The AGCM was used to perform sensitivity experiments and test the changes in the atmospheric response to different ENSO patterns and intensities.

The analysis of the observed data was carried out considering monthly values of (1) sea surface temperature (SST) from ERSSTv4 [

20], (2) interpolated outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) at the top of the atmosphere from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) [

21], (3) horizontal wind at 850 hPa (v850) and geopotential height at 200 hPa (z200) from National Center of Environmental Prediction / Department of Energy (NCEP/DOE Reanalysis 2) [

22]. We first computed the anomaly values of OLR, z200 and v850 fields by removing the seasonal cycle during the analyzed period (1979–2016). They were referred to as OLRa, z200a and v850a, respectively. Then, to discriminate between the two types of El Niño, Canonical and Modoki, we used the Niño3 and the El Niño Modoki (MI) indices, respectively. The Niño3 index was defined as the DJF SST anomaly averaged over the region (150° W-90° W, 5° S-5° N), while the MI index was calculated considering the improved definition given by Li et al. [

23]: MI = 3·[SSTa]

A − 2·[SSTa]

B − [SSTa]

C, where [SSTa]

X refers to the average of the DJF SST anomalies over the box X, where X can be A = [165° E-140° W, 10° S-10° N], B = [110° W-70° W, 15° S-5° N] and C = [125° E-145° E, 10 °S-20° N].

In order to analyze the atmospheric response using reanalysis data, correlation maps between these two ENSO indices (Niño3/Modoki index) and the OLRa, z200a and v850a fields were computed. Finally, in order to make more comparable results from reanalysis and model simulations, we also computed the composite map of z200 anomalies associated with Canonical El Niño and El Niño Modoki. They were obtained considering the Canonical and Modoki El Niño events separately. The El Niño3 (El Niño Modoki) years were selected as those years when the index was greater than 0.7σ

N3 (0.7σ

Mo), where σ

N3 (σ

Mo) represents the standard deviation of El Niño3 (El Niño Modoki) index over the period 1979–2016. Finally, given that the definition of El Niño Modoki index consists in the subtraction of different SSTa averaged over different boxes (A, B and C), large anomalies over the regions B and C could indicate an El Niño year even when the SSTa over the region A were small. Moreover, an El Niño could be selected as La Niña. Therefore, an additional constraint was included to define El Niño Modoki years: region A had to present strong SSTa. Thus, El Niño Modoki years were those when MI was higher than 0.7σ

Mo and [SSTa]

A was greater than 0.7σ

[SSTa]A, where σ

[SSTa]A represents the standard deviation of the SST anomalies over the region A. This methodology was also employed by Tedeschi et al. [

15].

Table 1 shows the El Niño3 and El Niño Modoki years. The years marked in gray were common, that is, they satisfied the criterion for strong Canonical or Modoki El Niño. These cases were classified as one or the other attending to the spatial distribution of the SST anomalies, in such a way that those common years with the stronger SST anomalies located in the region A were classified as El Niño Modoki years, and those with the maximum SST anomalies over the eastern equatorial Pacific as El Niño3 years. The final selection of years for the composite analysis is shown in

Table 2. The neutral years were selected as those when both Niño3 and Modoki indices were lower than 0.7 times the respective standard deviation.

Table 3 lists the years selected as neutral in the period (1979–2016).

The sensitivity of SH circulation to different ENSO patterns and intensities was addressed by performing idealized sensitivity experiments with the AGCM developed by the International Center for Theoretical Physics (ICTP-AGCM, hereafter Speedy; [

24,

25]). Speedy is a so-called intermediate complexity AGCM based on a spectral dynamical core. It is a sigma-coordinate, hydrostatic, spectral-transform model in the vorticity-divergence form with a semi-implicit treatment of gravity waves. Its prognostic variables are divergence, vorticity, absolute temperature and the surface pressure logarithm. The time stepping uses a leapfrog scheme (see Reference [

24] and references therein). The horizontal resolution corresponds to a triangular spectral truncation at total wavenumber 30 (T30), with a standard Gaussian grid of 96 by 48 points. This model has been previously used to study climate variability over South America many times, showing its suitability for these kind of studies [

26,

27].

Given that this study focused on the impacts of the positive phase of these ENSO patterns, we constructed two ensembles of experiments using as boundary conditions the SST anomaly patterns of Canonical El Niño and El Niño Modoki, separately. The boundary conditions were constructed by adding the monthly climatological SST over the period 1979–2016 to the regression of monthly observed SST anomalies onto the DJF Niño3 and MI indices. Experiments started on 1st October and finished on 31st March. Additionally, to study the atmospheric sensitivity to different El Niño intensities, all regressions maps were multiplied by a factor in order to make the maximum SSTa intensity equal to 1 and 3 °C, maintaining the same spatial structure of SST anomalies. We selected 1 °C because it is the standard deviation of the Niño3 region, and 3 °C because this intensity represents a strong Canonical El Niño event. To facilitate the comparison between both El Niño types, intensities of 1 and 3 °C were also considered for El Niño Modoki pattern. Therefore, we set up four experiments (summarized in

Table 1): Canonical El Niño 1 °C (Canonical_1C), Canonical El Niño 3 °C (Canonical_3C), El Niño Modoki 1 °C (Modoki_1C) and El Niño Modoki 3 °C (Modoki_3C).

Figure 1b,c show the average DJF SST anomaly patterns associated with Canonical El Niño and El Niño Modoki with which the model was forced (see

Table 4).

Each experiment consisted of 22 simulations, all of them initialized with different atmospheric initial conditions but all having the same SST as boundary conditions. The model started from rest and it was initialized by introducing a random diabatic forcing during the first days of the simulations. The spatial distribution of the diabatic forcing changed in consecutive simulations, generating different initial conditions. Additionally, a 22-member CONTROL experiment was constructed, with climatological SST as boundary conditions. Although all simulations were started on 1st October and finished on 31st March, only the season DJF was considered in this study.

To calculate the model forced response associated with each type of El Niño, we considered the ensemble mean of each experiment, which filtered out the internal atmospheric variability [

28,

29,

30], and subtracted the CONTROL mean conditions.

Finally, in this study we have used the El Niño patterns obtained from the ERSSTv4 dataset to force the model. The patterns that can be obtained using ERSSTv5 present large similarities with those one from ERSSTv4 (not shown) and the small differences were negligible for speedy resolution (which was 3.7°).

On the other hand, to analyze wave propagation, we also computed the horizontal components of the quasi-stationary wave propagation (

Fs) considering the definition given by Plumb [

31]:

where

is the latitude,

is the Earth’s radius,

is the angular rotation rate of the Earth,

and

are the eddy horizontal geostrophic wind components at 200 hPa averaged over DJF, and

is the eddy geopotential height at 200 hPa averaged over DJF. For steady conservative waves, this field is nondivergent and, for slowly varying almost plane waves it is parallel to the group velocity [

29]. Therefore, this measure helped us to better interpret the Rossby waves propagation associated with the El Niño phenomenon in the SH.

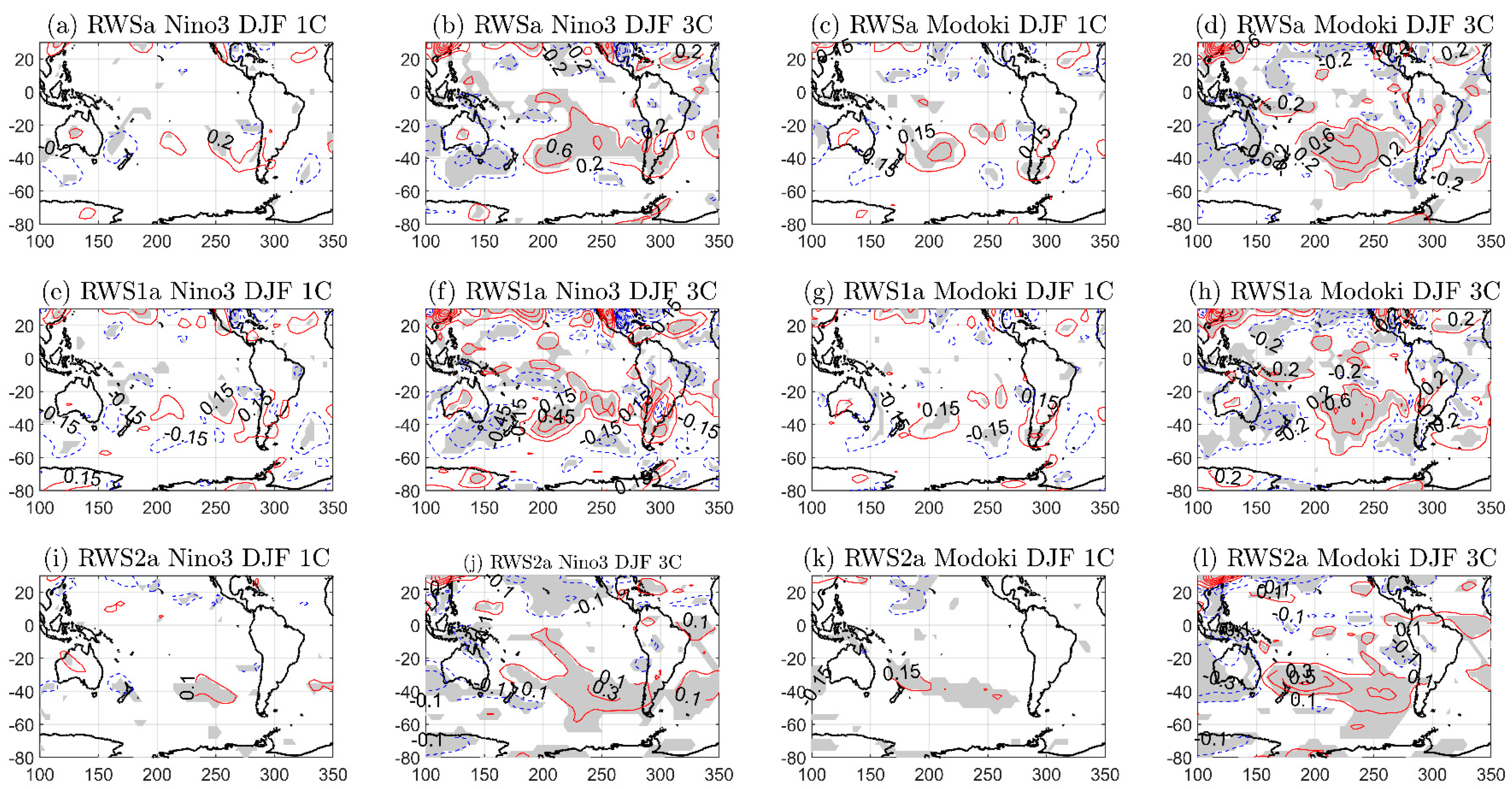

Finally, for a better understanding of the origin of these Rossby waves, the Rossby Wave Sources (RWS) were also computed in each experiment following the definition:

where V

χ represents the divergent wind component and ξ = (f + ζ) the absolute vorticity. Equation (2) can be also expressed as:

where the first term, RWS1 = −ξ ∇.V

χ, is known as the vortex stretching and the second one, RWS2 = −V

χ ·∇ξ, represents the advection of absolute vorticity by the divergent wind component. The relative vorticity ζ was computed using the rotational daily horizontal winds. In the SH, negative (positive) RWS are associated with a cyclonic (anticyclonic) circulation.

5. Summary and Conclusions

In this study we have analyzed the SH atmospheric response to different El Niño patterns and intensities paying special attention to the teleconnections and impacts on SSA, a region located between 20° S and 40° S with watershed in the tropical Atlantic and whose rainfall variability at interannual times scales is strongly influenced by changes in the equatorial Pacific SSTs. Several previous studies have already shown that the El Niño influence on SSA happens through the generation of quasi-stationary Rossby waves. However, it is not yet clear whether the induced wave trains depend on the El Niño pattern and/or its intensity.

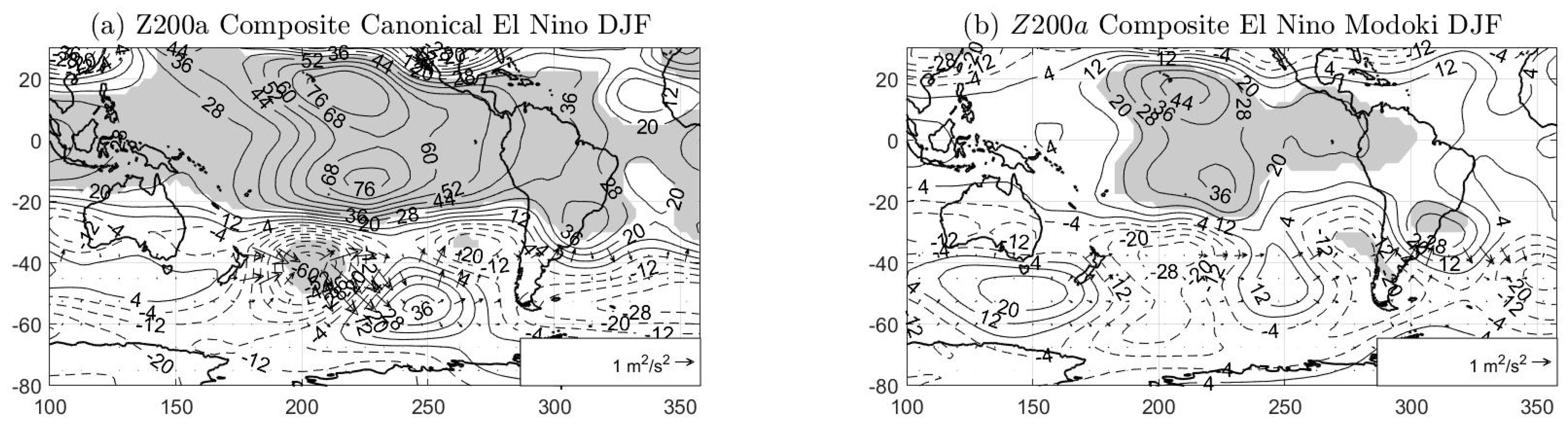

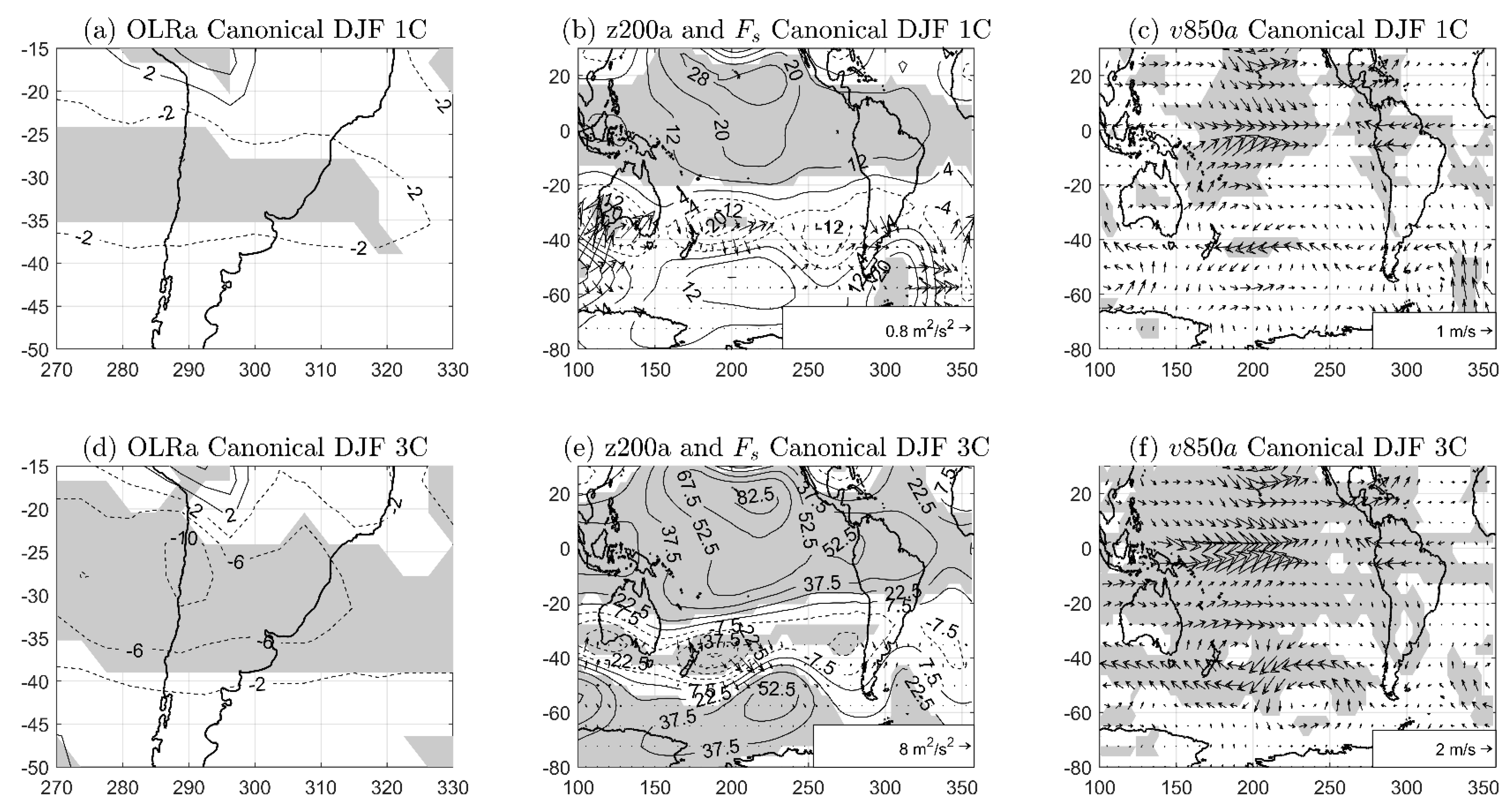

In agreement with observations, the model’s results showed that Canonical_3C experiment induced two Rossby wave trains, a large one that emanated from the subtropical western south Pacific and propagated southeastward, and a shorter one that grew up in the eastern subtropical South Pacific (see

Figure 4e). They both presented a barotropic behavior on extratropical latitudes (compare

Figure 4e,f), though it was the shorter one that played the main role in generating OLR anomalies over SSA, through (1) an increase of the cyclonic vorticity advection in upper levels, and (2) a strengthening of the northerlies bringing moisture toward SSA at lower levels. Unlike observations, however, the propagation of this shorter Rossby wave train did not show any statistically significant anticyclone over the Atlantic watershed of SSA (compare

Figure 2b and

Figure 4e).

The comparison of the 1 °C and 3 °C Canonical experiments showed that the increase of the SST anomalies over the eastern equatorial Pacific enhanced the RWS intensity. The statistically significant RWS signal located between Australia and New Zealand (over the western Chilean-Peruvian coast) was related to the generation of the large (short) Rossby wave train. While the larger wave was mainly related to RWS1, the shorter one presented contributions from both RWS1 and RWS2. Finally, the comparison of the z200 anomaly patterns from both Canonical experiments showed that the Speedy response was approximately linear with the increase of the SST anomalies. For the Canonical_1C experiment, the statistically significant reduction of OLR over SSA could be related to the intensification of the upper level jet stream.

The El Niño Modoki impact on SSA is more debated and there is currently no consensus regarding the influence of this ENSO pattern on SSA. The results from reanalysis here did not show any statistically significant signal over SSA. However, the model’s results showed that the impact of El Niño Modoki on SSA depended on the intensity of the SST anomalies, in such a way that increasing the SST anomalies of this pattern induced statistically significant OLR anomalies over SSA. While El Niño Modoki_1C did not show any statistically significant signal in the z200 anomaly pattern, El Niño Modoki_3C generated a large Rossby wave train that emanated from the subtropical western south Pacific and reached southern SA. The origin of this wave could be related to the negative RWS values developed between Australia and New Zealand (see

Figure 6d), whose main contribution came from RWS1 (see

Figure 6d,h,l). Finally, unlike Canonical El Niño, the z200 response to El Niño Modoki 3C presented a clear Gill-Matsuno quadrupole response over the tropical atmosphere [

34,

35] and, comparing El Niño Modoki_1C with 3C, the atmospheric response to this El Niño pattern presented a more non-linear behavior than in the case of Canonical El Niño (compare

Figure 5b,e, on the one hand, and

Figure 4b,e on the other hand).

Therefore, the model’s results suggested that SSA was more sensitive to SST anomalies over the region of Canonical El Niño, given that the eastern El Niño needed weaker anomalies to induce statistically significant OLR anomalies. In the case of El Niño Modoki, as the atmosphere was less responsive to the SST pattern, it needed larger SST intensities in order to overcome the internal atmospheric variability. This result may have been model dependent and should be tested with other models. Finally, the establishment of teleconnections from the tropics depends on the right simulation of the mean state. Speedy presented a northward bias in the position of the upper level jet (not shown) that could directly influence the wave propagation in the extratropics, and therefore, this could be one reason why Speedy did not present wave propagation until South America for the Canonical El Niño case. Nevertheless, Speedy captured the main dynamics and as an intermediate complexity AGCM it allowed many sensitivity experiments to be performed that have advanced the understanding of teleconnections. Another source of uncertainty could have come from the choice of a particular dataset for the definition of the climatology and spatial patterns that were used for the sensitivity experiments. However, the model’s results shown in this manuscript are consistent with the differing effects of El Niño Modoki over SSA found in the reanalysis and in previous works.