Identification of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean and Preliminary Functional Analysis of Its Drought-Responsive Candidate Genes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Nomenclature of the FLA Gene Family

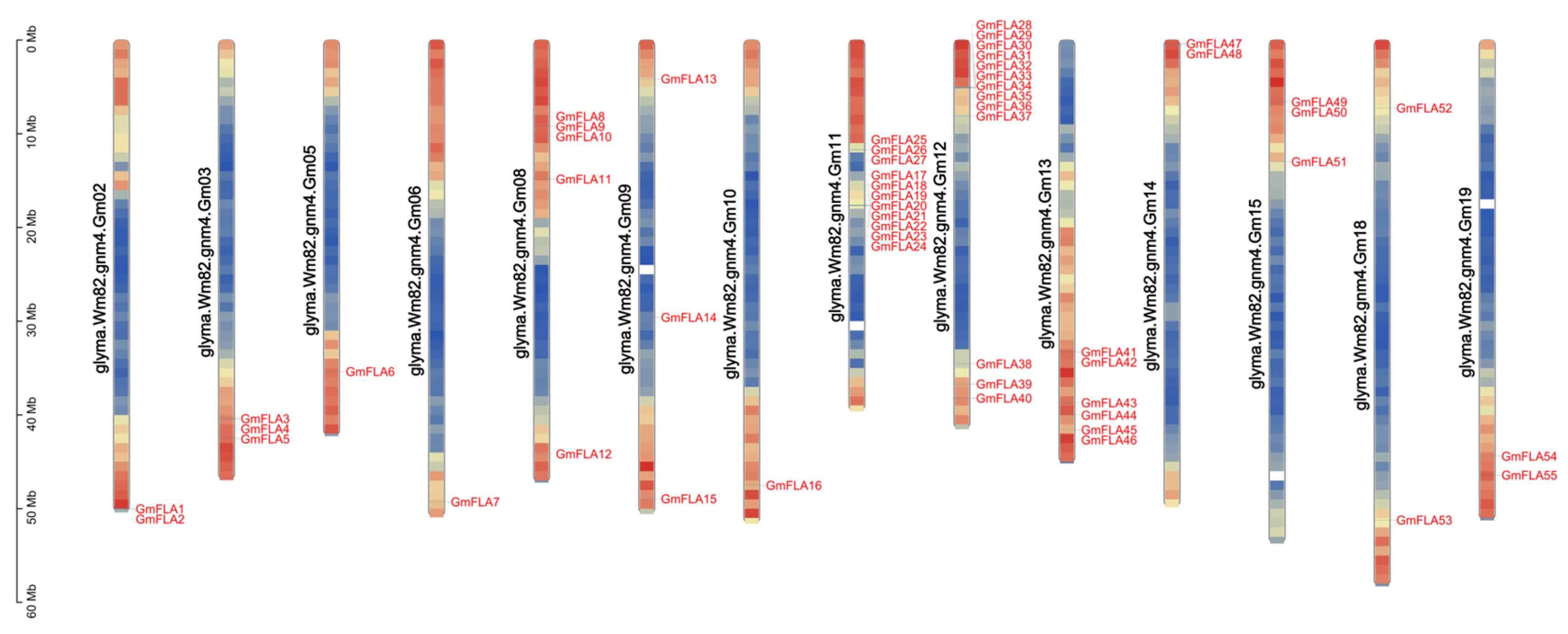

2.2. Chromosomal Distribution and Gene Localization

2.3. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties of Encoded Proteins

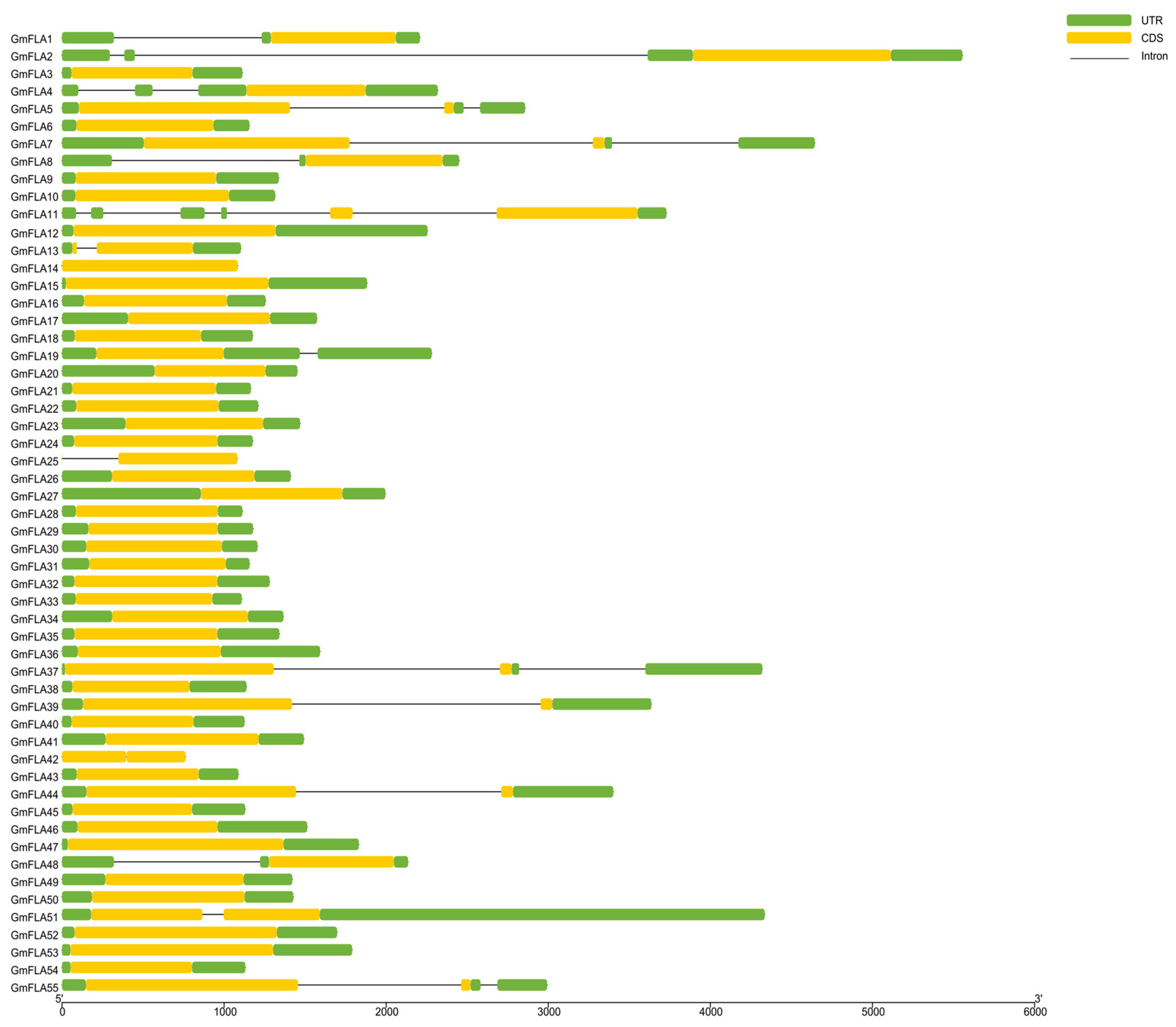

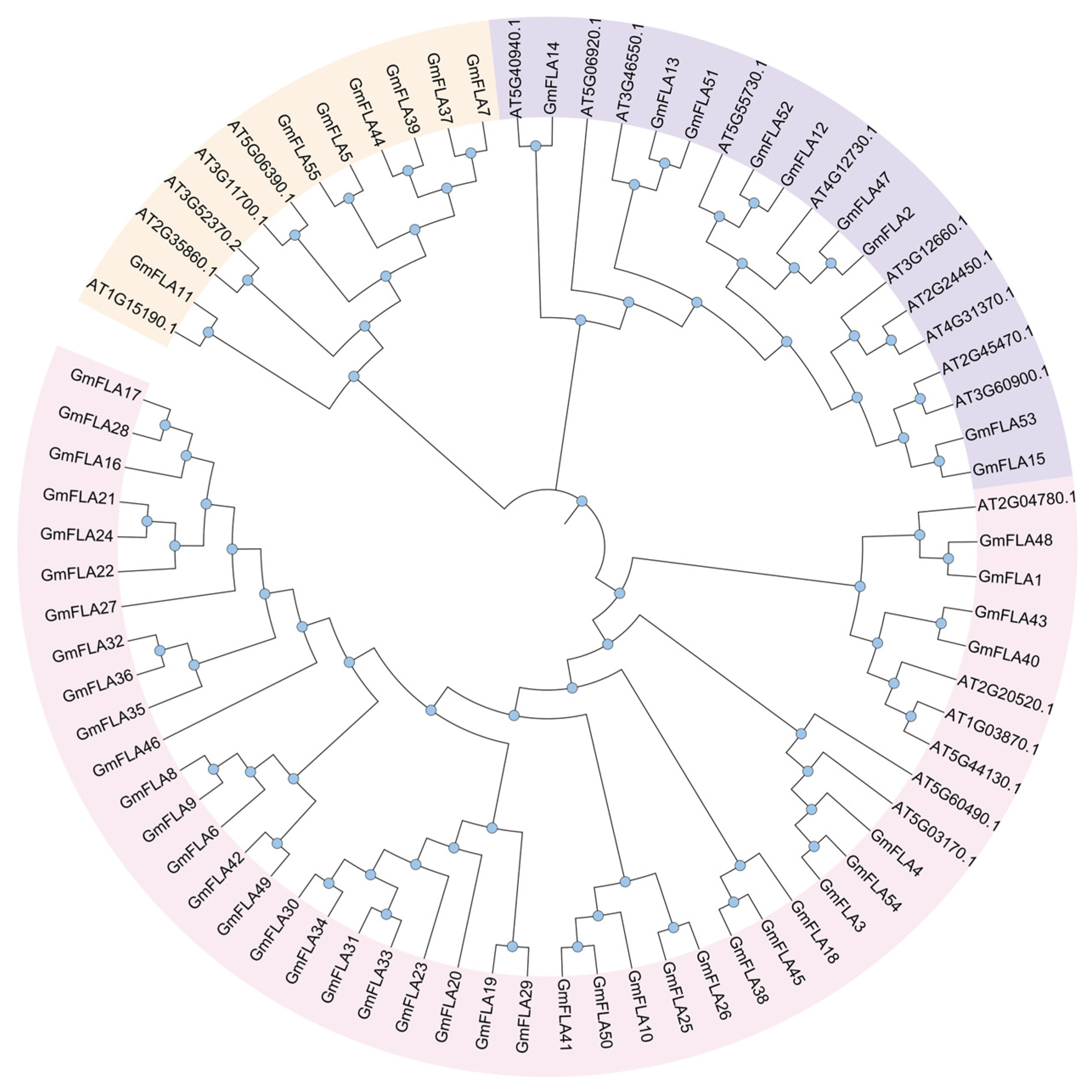

2.4. Structural and Phylogenetic Analysis of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean

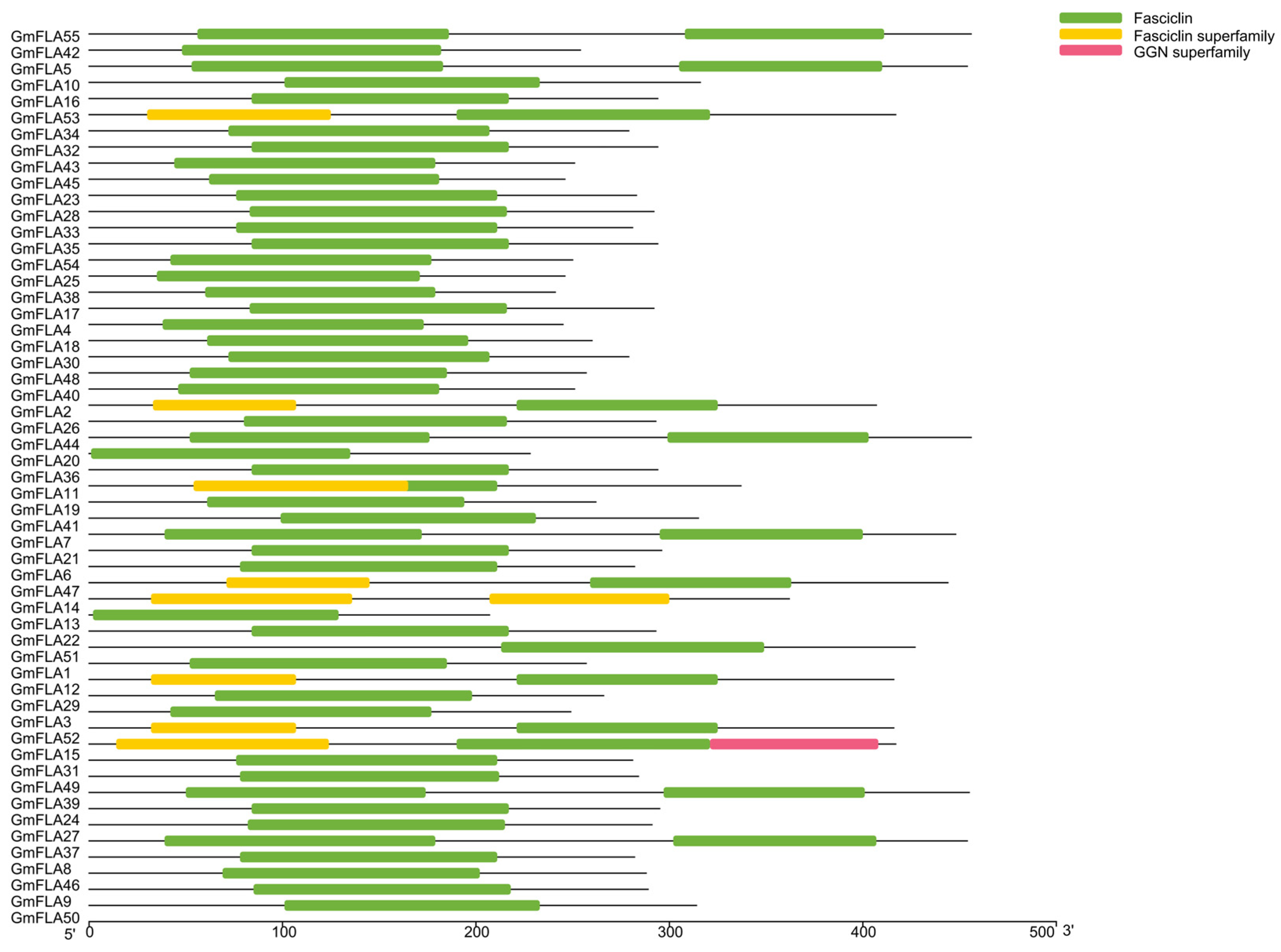

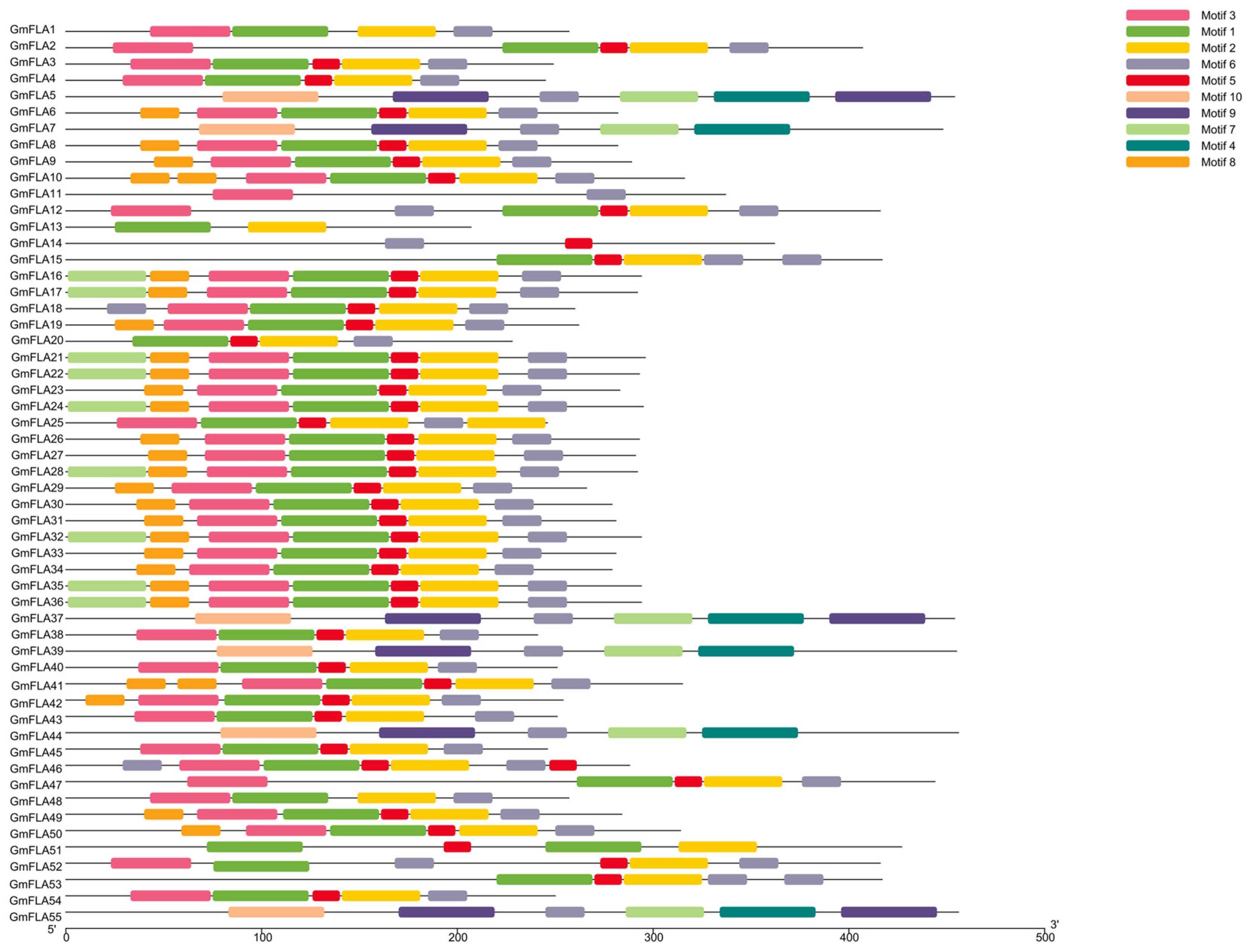

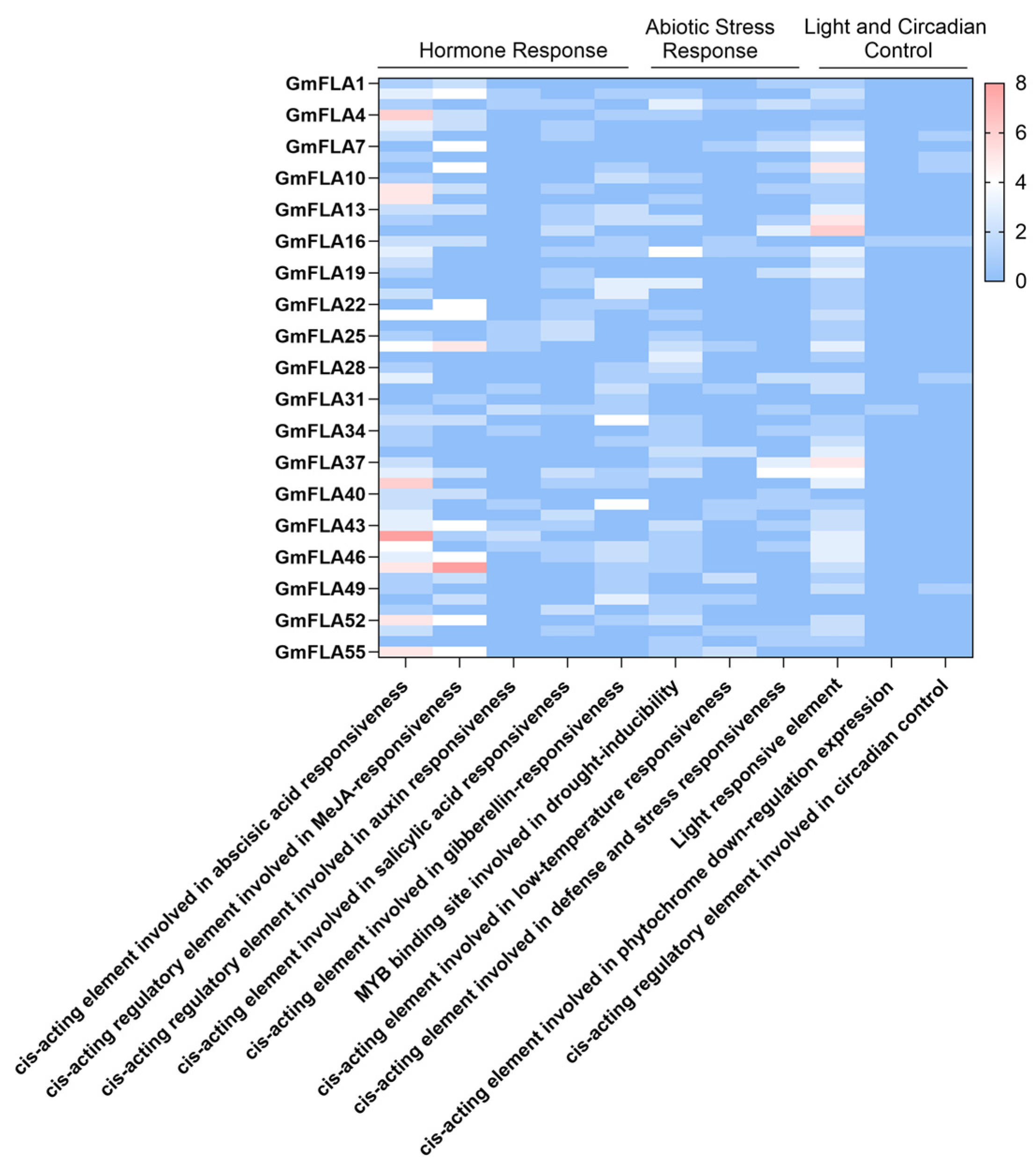

2.5. Analysis of the Conserved Domains and Motifs in the Soybean FLA Gene Family

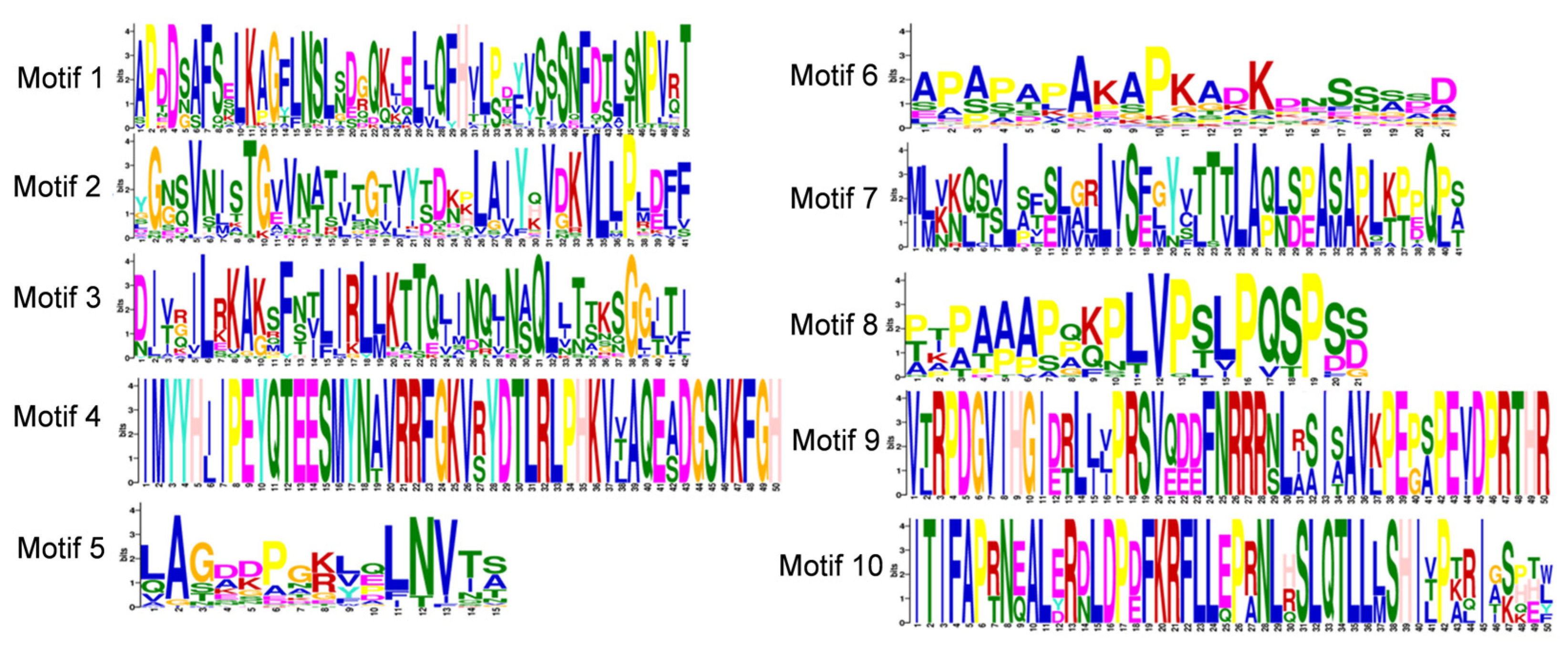

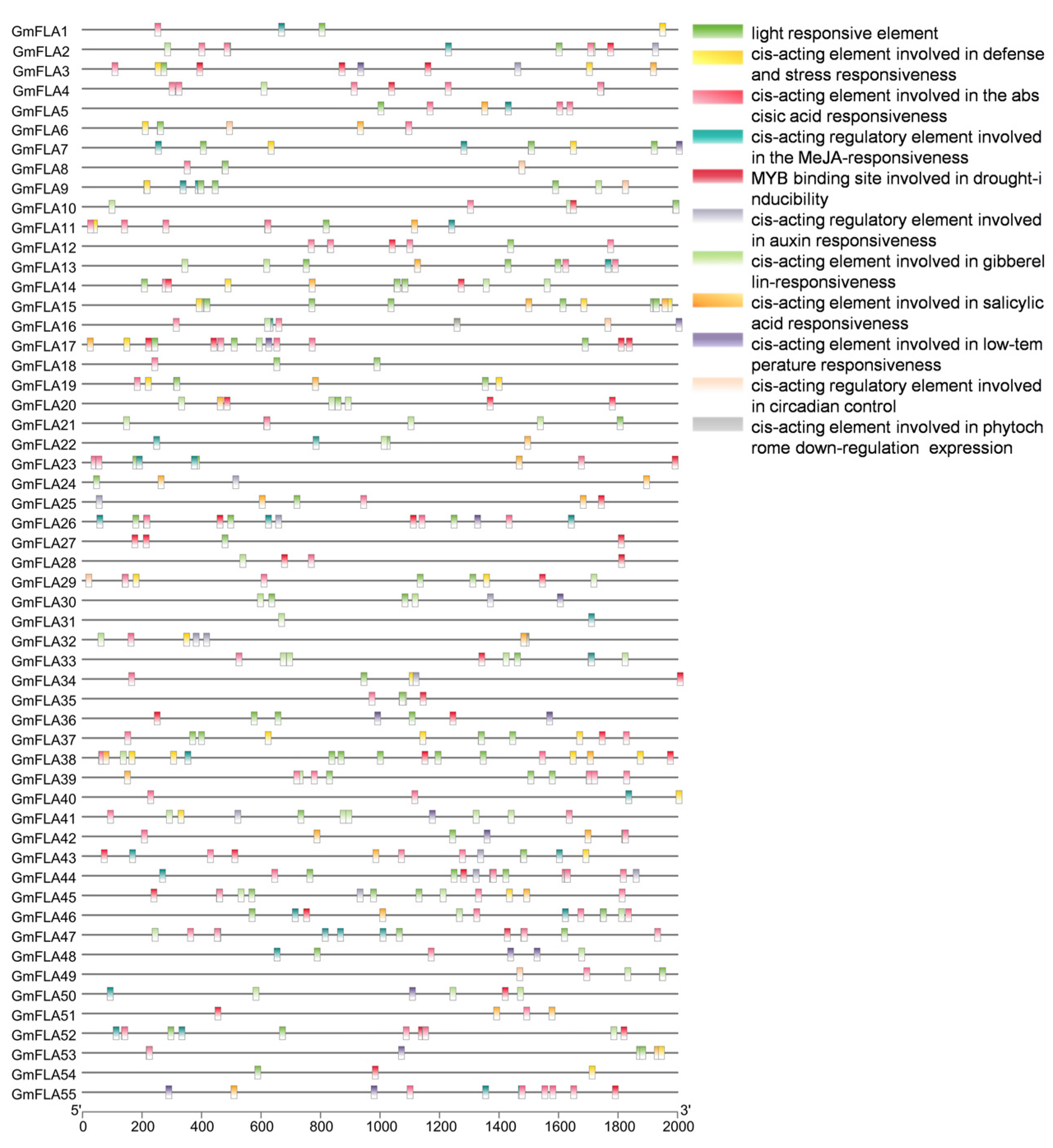

2.6. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the Soybean FLA Gene Family

2.7. Preliminary Screening of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean for Drought Response

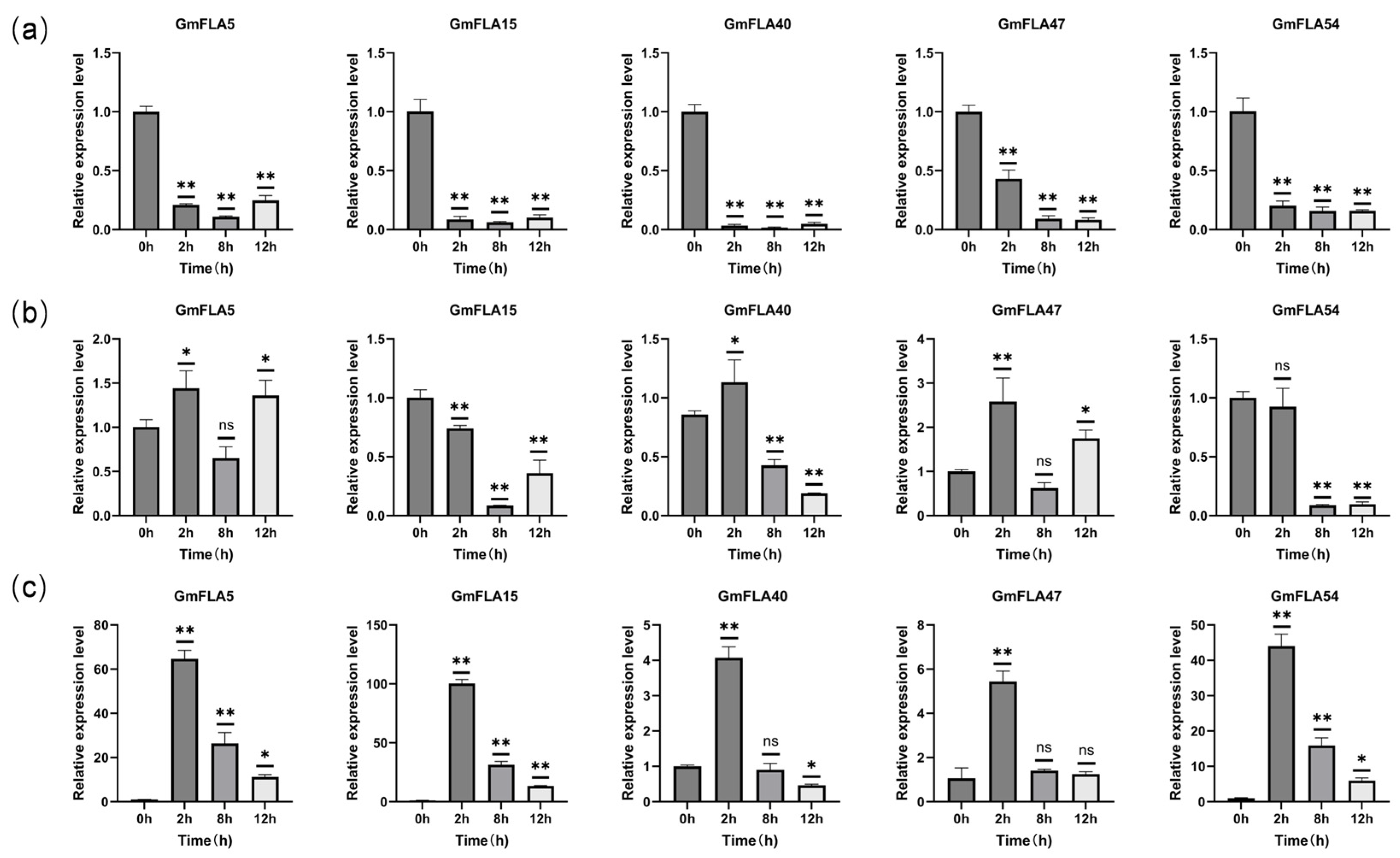

2.8. Expression Patterns of Candidate FLA Genes Under Different Stress Conditions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of FLA Family Members in Soybean

4.2. Chromosomal Localization and Physicochemical Properties Analysis of the Soybean FLA Gene Family

4.3. Analysis of Conserved Domains, Motifs, and Gene Structures in the Soybean FLA Gene Family

4.4. Evolutionary Analysis and Cis-Acting Element Analysis of the Soybean FLA Gene Family

4.5. Screening of Drought Response Candidate Genes

4.6. Plant Materials and Treatment Methods

4.7. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armingol, E.; Baghdassarian, H.M.; Lewis, N.E. The diversification of methods for studying cell–cell interactions and communication. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2024, 25, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Structure and growth of plant cell walls. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, W.; Li, Y.; Zou, J.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z. Drought shortens cotton fiber length by inhibiting biosynthesis, remodeling and loosening of the primary cell wall. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 200, 116827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, L.; Sharif, R.; Meng, J.; Gulzar, S.; Yi, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhan, H.; Liu, H.; et al. The banana MaFLA27 confers cold tolerance partially through modulating cell wall remodeling. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 290, 138748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinski, A.; Betekhtin, A.; Kwasniewska, J.; Chajec, L.; Wolny, E.; Hasterok, R. 3,4-Dehydro-L-proline Induces Programmed Cell Death in the Roots of Brachypodium distachyon. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Ma, M.; Niu, Q.; Eisert, R.J.; Wang, X.; Das, P.; Lechtreck, K.F.; Dutcher, S.K.; Zhang, R.; Brown, A. Mastigoneme structure reveals insights into the O-linked glycosylation code of native hydroxyproline-rich helices. Cell 2024, 187, 1907–1921.e1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, M.; Velasquez, S.M.; Jamet, E.; Estevez, J.M.; Albenne, C. An update on post-translational modifications of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins: Toward a model highlighting their contribution to plant cell wall architecture. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Johnson, K. Arabinogalactan proteins–Multifunctional glycoproteins of the plant cell wall. Cell Surf. 2023, 9, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Miao, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Cao, J. Arabinogalactan Proteins: Focus on the Role in Cellulose Synthesis and Deposition during Plant Cell Wall Biogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, Y.; Johnson, K.L.; McKenna, J.A.; Bacic, A.; Schultz, C.J. The complex structures of arabinogalactan-proteins and the journey towards understanding function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 47, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Showalter, A.M.; Keppler, B.; Lichtenberg, J.; Gu, D.; Welch, L.R. A bioinformatics approach to the identification, classification, and analysis of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 485–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Blervacq, A.S.; Vasseur, J.; Hilbert, J.L. Arabinogalactan-proteins in Cichorium somatic embryogenesis: Effect of beta-glucosyl Yariv reagent and epitope localisation during embryo development. Planta 2000, 211, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, G.J. The FLA4-FEI Pathway: A Unique and Mysterious Signaling Module Related to Cell Wall Structure and Stress Signaling. Genes 2021, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Zou, T.; Zhang, K.; Xiong, P.; Zhou, F.; Chen, H.; Li, G.; Zheng, K.; Han, Y.; Peng, K.; et al. DEAP1 encodes a fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein required for male fertility in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 1430–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.L.; Kibble, N.A.; Bacic, A.; Schultz, C.J. A fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-protein (FLA) mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana, fla1, shows defects in shoot regeneration. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhao, J. Genome-wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of the arabinogalactan protein gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Exp. Bot 2010, 61, 2647–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faik, A.; Abouzouhair, J.; Sarhan, F. Putative fasciclin-like arabinogalactan-proteins (FLA) in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and rice (Oryza sativa): Identification and bioinformatic analyses. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2006, 276, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Zheng, T.; Chu, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Su, X. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Fasciclin-Like Arabinogalactan Protein Gene Family Reveals Differential Expression Patterns, Localization, and Salt Stress Response in Populus. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Yin, T.; Wu, H. Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis of the Fasciclin-like Arabinogalactan Proteins (FLAs) in Salicacea and Identification of Secondary Tissue Development-Related Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Q.; Xu, W.L.; Gong, S.Y.; Li, B.; Wang, X.L.; Xu, D.; Li, X.B. Characterization of 19 novel cotton FLA genes and their expression profiling in fiber development and in response to phytohormones and salt stress. Physiol. Plant 2008, 134, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Cao, J.; Lin, S. Comprehensive Analysis of Arabinogalactan Protein-Encoding Genes Reveals the Involvement of Three BrFLA Genes in Pollen Germination in Brassica rapa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Yao, Y.; Ding, Z.; Pan, X.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, A.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; et al. Characterization of the FLA Gene Family in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) and the Expression Analysis of SlFLAs in Response to Hormone and Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Jiang, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, F.; Zhang, H. Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan proteins, PtFLAs, play important roles in GA-mediated tension wood formation in Populus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xin, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Dai, H.; Sun, R.; Frazier, T.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q. Xylem sap in cotton contains proteins that contribute to environmental stress response and cell wall development. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2015, 15, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Q.; Gong, S.Y.; Xu, W.L.; Li, W.; Li, P.; Zhang, C.J.; Li, D.D.; Zheng, Y.; Li, F.G.; Li, X.B. A fasciclin-like arabinogalactan protein, GhFLA1, is involved in fiber initiation and elongation of cotton. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 1278–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, C.P.; Mansfield, S.D.; Stachurski, Z.H.; Evans, R.; Southerton, S.G. Fasciclin-like arabinogalactan proteins: Specialization for stem biomechanics and cell wall architecture in Arabidopsis and Eucalyptus. Plant J. 2010, 62, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Kim, Y.; Guo, Y.; Stevenson, B.; Zhu, J.K. The Arabidopsis SOS5 locus encodes a putative cell surface adhesion protein and is required for normal cell expansion. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.J.; Xue, H.; Acet, T. The Arabidopsis thaliana FASCICLIN LIKE ARABINOGALACTAN PROTEIN 4 gene acts synergistically with abscisic acid signalling to control root growth. Ann. Bot 2014, 114, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allelign Ashagre, H.; Zaltzman, D.; Idan-Molakandov, A.; Romano, H.; Tzfadia, O.; Harpaz-Saad, S. FASCICLIN-LIKE 18 Is a New Player Regulating Root Elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 645286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Lu, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, P.; Li, N.; Ma, Y.; Wu, J.; Ma, Y. Function and Expression Analysis on StFLA4 in Response to Drought Stress and Tuber Germination in Potato. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Kong, F. Soybean. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R902–R904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffique, S.; Hussain, S.; Kang, S.M.; Imran, M.; Injamum-Ul-Hoque, M.; Khan, M.A.; Lee, I.J. Phytohormonal modulation of the drought stress in soybean: Outlook, research progress, and cross-talk. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1237295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Shafee, T.; Mudiyanselage, A.M.; Ratcliffe, J.; MacMillan, C.P.; Mansfield, S.D.; Bacic, A.; Johnson, K.L. Distinct functions of FASCILIN-LIKE ARABINOGALACTAN PROTEINS relate to domain structure. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Song, Q. Polyploidy and diploidization in soybean. Mol. Breed 2023, 43, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Dong, S. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of Seedling-Stage Soybean Responses to PEG-Simulated Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | AA | MW (kDa) | pI | II | AI | GRAVY | Location | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmFLA1 | Glyma.02G307700 | 256 | 27,139.59 | 5.03 | 51.84 | 86.17 | 0.134 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA2 | Glyma.02G308700 | 406 | 43,557.75 | 6.37 | 36.8 | 91.16 | −0.002 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA3 | Glyma.03G179900 | 248 | 26,301.83 | 5.51 | 26.81 | 88.91 | 0.083 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA4 | Glyma.03G180000 | 244 | 25,780.24 | 6.82 | 21.61 | 90.82 | 0.052 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA5 | Glyma.03G204300 | 453 | 50,149.18 | 5.98 | 58.21 | 94.97 | −0.235 | cyto | Yes |

| GmFLA6 | Glyma.05G161900 | 281 | 29,174.37 | 9.12 | 41.47 | 95.59 | 0.093 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA7 | Glyma.06G308600 | 447 | 49,665.66 | 6.36 | 54.31 | 89.69 | −0.287 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA8 | Glyma.08G119400 | 281 | 29,247.45 | 9.14 | 44.82 | 97.3 | 0.095 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA9 | Glyma.08G119500 | 288 | 29,955.41 | 9.34 | 44.01 | 97.67 | 0.111 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA10 | Glyma.08G119600 | 315 | 32,662.67 | 8.47 | 45.63 | 98.76 | 0.124 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA11 | Glyma.08G183700 | 336 | 36,952.17 | 5.92 | 72.04 | 89.17 | −0.035 | chlo | No |

| GmFLA12 | Glyma.08G329900 | 415 | 43,692.78 | 5.81 | 37.53 | 93.01 | −0.054 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA13 | Glyma.09G048100 | 206 | 21,492.33 | 4.53 | 42.49 | 93.2 | 0.178 | golg | No |

| GmFLA14 | Glyma.09G119800 | 361 | 39,979.15 | 6.53 | 40.55 | 87.59 | −0.168 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA15 | Glyma.09G267700 | 416 | 42,505.2 | 5.59 | 48.51 | 97.45 | 0.189 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA16 | Glyma.10G245800 | 293 | 31,032.8 | 8.82 | 43.86 | 99.52 | 0.063 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA17 | Glyma.11G147800 | 291 | 30,785.5 | 9.03 | 36.87 | 95.88 | 0.066 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA18 | Glyma.11G148100 | 259 | 27,402.34 | 7.96 | 33.06 | 92.32 | 0.036 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA19 | Glyma.11G148200 | 261 | 27,944.04 | 8.62 | 40.07 | 100.15 | 0.136 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA20 | Glyma.11G148300 | 227 | 24,078.73 | 6.5 | 33.24 | 109.12 | 0.263 | golg | No |

| GmFLA21 | Glyma.11G148400 | 295 | 30,969.58 | 8.51 | 44.79 | 96.58 | 0.047 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA22 | Glyma.11G148500 | 292 | 30,793.46 | 9.2 | 45.12 | 94.9 | 0.02 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA23 | Glyma.11G148501 | 282 | 29,640.22 | 8.67 | 50.13 | 104.15 | 0.083 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA24 | Glyma.11G148700 | 294 | 30,890.6 | 8.53 | 45.22 | 97.18 | 0.097 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA25 | Glyma.11G155886 | 245 | 25,833.58 | 7.85 | 30.4 | 98.65 | 0.027 | chlo | No |

| GmFLA26 | Glyma.11G156304 | 292 | 30,731.29 | 8.93 | 39.59 | 90.79 | 0.041 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA27 | Glyma.11G156513 | 290 | 30,551.27 | 6.74 | 38.19 | 103.97 | 0.163 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA28 | Glyma.12G068900 | 291 | 30,717.5 | 9.24 | 39.58 | 99.9 | 0.089 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA29 | Glyma.12G069400 | 265 | 28,023.12 | 7.73 | 37.85 | 105.25 | 0.182 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA30 | Glyma.12G069500 | 278 | 29,334.82 | 6.84 | 52.07 | 100.04 | 0.094 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA31 | Glyma.12G069601 | 280 | 29,451.91 | 8.69 | 50.82 | 98.96 | 0.093 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA32 | Glyma.12G069700 | 293 | 30,964.66 | 7.81 | 48.53 | 96.55 | 0.027 | chlo, vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA33 | Glyma.12G069800 | 280 | 29,437.89 | 8.69 | 52.19 | 98.29 | 0.085 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA34 | Glyma.12G069900 | 278 | 29,347.87 | 7.88 | 54.31 | 100.04 | 0.094 | chlo, extr | Yes |

| GmFLA35 | Glyma.12G070000 | 293 | 30,998.68 | 7.81 | 48.53 | 95.22 | 0.024 | chlo, vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA36 | Glyma.12G070200 | 293 | 30,936.6 | 7.81 | 48.24 | 95.9 | 0.019 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA37 | Glyma.12G096300 | 453 | 50,393.5 | 6.58 | 56.69 | 88.9 | −0.331 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA38 | Glyma.12G173800 | 240 | 25,483.09 | 9.22 | 28.99 | 97.54 | 0.051 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA39 | Glyma.12G190700 | 454 | 50,214.24 | 6.13 | 52.12 | 92.11 | −0.261 | vacu | Yes |

| GmFLA40 | Glyma.12G207600 | 250 | 26,345.18 | 9.19 | 31.43 | 88.6 | −0.078 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA41 | Glyma.13G226000 | 314 | 32,532.23 | 8.73 | 44.52 | 91.05 | 0.072 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA42 | Glyma.13G226100 | 253 | 26,568.34 | 9.48 | 37.27 | 91.82 | −0.022 | chlo | No |

| GmFLA43 | Glyma.13G293500 | 250 | 26,589.38 | 8.56 | 31.46 | 93.28 | −0.109 | extr | Yes |

| GmFLA44 | Glyma.13G311000 | 455 | 50,328.36 | 6.2 | 53.1 | 91.93 | −0.264 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA45 | Glyma.13G327100 | 245 | 26,280.28 | 9.56 | 27.45 | 94.37 | 0.052 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA46 | Glyma.13G327300 | 287 | 29,843.57 | 9.25 | 33.23 | 102.93 | 0.208 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA47 | Glyma.14G004200 | 443 | 47,882.64 | 7.29 | 41.38 | 89.73 | −0.077 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA48 | Glyma.14G005300 | 256 | 27,224.66 | 5.05 | 47.17 | 85.04 | 0.102 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA49 | Glyma.15G086000 | 283 | 29,817.32 | 9.44 | 37.12 | 101.06 | 0.113 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA50 | Glyma.15G086100 | 313 | 32,586.38 | 9.22 | 46.8 | 91.02 | 0.036 | chlo | Yes |

| GmFLA51 | Glyma.15G155400 | 426 | 45,166.65 | 5.68 | 45.51 | 105.77 | 0.286 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA52 | Glyma.18G076600 | 415 | 43,368.38 | 5.8 | 34.03 | 93.71 | −0.021 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA53 | Glyma.18G222200 | 416 | 42,488.34 | 5.89 | 47.02 | 98.37 | 0.18 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA54 | Glyma.19G180700 | 249 | 26,278.71 | 5.51 | 26.22 | 90.92 | 0.074 | plas | Yes |

| GmFLA55 | Glyma.19G201600 | 455 | 50,578.56 | 6.21 | 61.05 | 90.68 | −0.308 | cyto | Yes |

| Dataset | Group | Fold Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmFLA5 | GmFLA15 | GmFLA40 | GmFLA47 | GmFLA54 | ||

| GSE102749 | water control—5 h water stress (root) | 0.2393 | 0.5564 | 0.9766 | 0.1159 | 0.0855 |

| water control—48 h water stress (root) | −0.18 | −0.0293 | −0.287 | 0.162 | −0.927 | |

| GSE6553 | water control—2 h water stress (root) | 0.571 | 0.5026 | 0.7178 | −0.0241 | 0.7653 |

| water control—10 h water stress (root) | 0.855 | 0.848 | 0.835 | 0.0888 | 0.799 | |

| GSE49537 | water control—30 min water stress (root) | 0.1684 | 0.5878 | 0.4536 | 0.4040 | 0.3544 |

| water control—2 h water stress (root) | 0.0947 | 0.4811 | 2.1924 | 0.5313 | 0.2129 | |

| water control—5 h water stress (root) | 0.6182 | 1.6081 | 1.7033 | 1.0337 | 1.6471 | |

| water control—30 min water stress (leaf) | 0.3239 | 1.3927 | −0.2175 | 0.2456 | −0.1039 | |

| water control—2 h water stress (leaf) | 1.5716 | 2.5599 | 2.0871 | 1.2721 | 0.6380 | |

| water control—5 h water stress (leaf) | 2.7291 | 5.0547 | 5.4540 | 2.4745 | 2.5847 | |

| GSE29663 | water control—6 d water stress (leaf) | 0.2191 | 0.0645 | 2.4010 | 1.2771 | 1.0363 |

| GSE40604 | water control—5 d water stress (leaf) | 1.5291 | −0.0531 | 0.9784 | 1.2180 | 0.5417 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Dou, J.; Wang, C.; Yao, Z. Identification of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean and Preliminary Functional Analysis of Its Drought-Responsive Candidate Genes. Genes 2025, 16, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121425

Zhang J, Yang L, Dou J, Wang C, Yao Z. Identification of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean and Preliminary Functional Analysis of Its Drought-Responsive Candidate Genes. Genes. 2025; 16(12):1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121425

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiyue, Lina Yang, Jingxuan Dou, Cong Wang, and Zhengpei Yao. 2025. "Identification of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean and Preliminary Functional Analysis of Its Drought-Responsive Candidate Genes" Genes 16, no. 12: 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121425

APA StyleZhang, J., Yang, L., Dou, J., Wang, C., & Yao, Z. (2025). Identification of the FLA Gene Family in Soybean and Preliminary Functional Analysis of Its Drought-Responsive Candidate Genes. Genes, 16(12), 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16121425