Imprinting Disorders and Epigenetic Alterations in Children Conceived by Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Mechanisms, Clinical Outcomes, and Prenatal Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

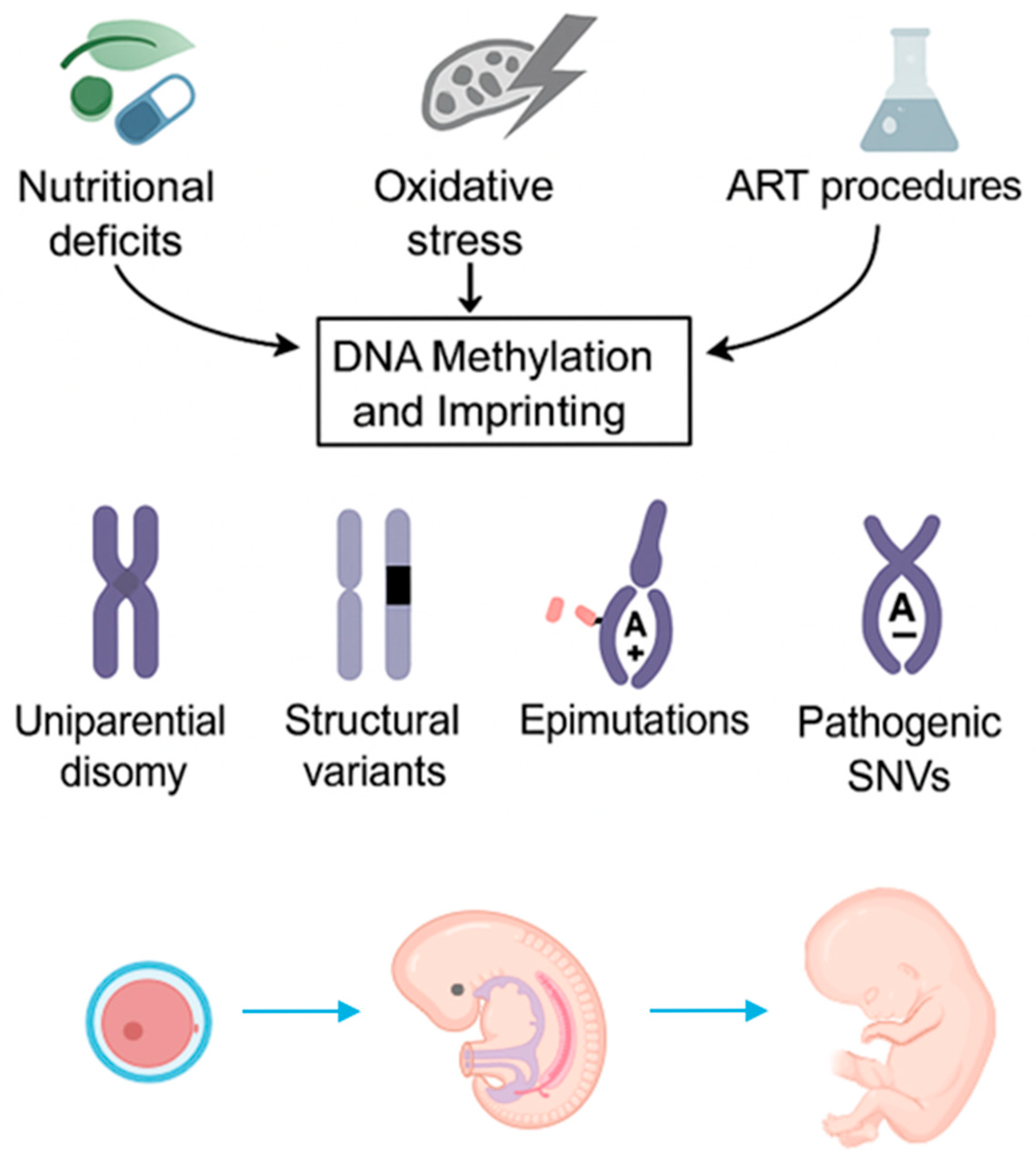

2. Mechanisms of Imprinting Disorders

2.1. Ovarian Hyperstimulation

2.2. In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) and Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI)

2.3. Embryo Culture

2.4. Cryopreservation

2.5. Embryo Transfer (ET)

2.6. Combined ART Procedures

3. ART-Related Imprinting Disorders

3.1. Beckwith–Wiedemann Syndrome

3.2. Angelman Syndrome

3.3. Prader–Willi Syndrome

3.4. Silver–Russell Syndrome

3.5. Other Imprinting Disorders

3.6. Multi-Locus Imprinting Disturbances (MLIDs)

4. Prenatal Diagnosis

4.1. Preimplantation Genetic Testing (PGT)

4.2. Disorder-Specific Prenatal Features

4.3. Genetic Counseling

5. Long-Term Outcomes

5.1. Cardiometabolic Outcomes

5.2. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

5.3. Growth Trajectory

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted Reproductive Technology |

| AS | Angelman Syndrome |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| BWS | Beckwith–Wiedemann Syndrome |

| ESC | Embryonic Stem Cell |

| ET | Embryo Transfer |

| HDAC | Histone Deacetylase |

| ICR | Imprinting Control Region |

| ICSI | Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection |

| ID | Imprinting Disorder |

| IVF | In Vitro Fertilization |

| MAGEL2 | MAGE Family Member L2 |

| MKRN3 | Makorin Ring Finger Protein 3 |

| NAD | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide |

| NECDIN | Neuronal Differentiation Protein |

| PGT | Preimplantation Genetic Testing |

| PWS | Prader–Willi Syndrome |

| SAM | S-Adenosylmethionine |

| SNRPN | Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Polypeptide N |

| SNV | Single-Nucleotide Variant |

| SRS | Silver–Russell Syndrome |

| UBE3A | Ubiquitin Protein Ligase E3A |

| UPD | Uniparental Disomy |

| snRNA | Small Nucleolar RNA |

References

- Kushnir, V.A.; Barad, D.H.; Albertini, D.F.; Darmon, S.K.; Gleicher, N. Systematic review of worldwide trends in assisted reproductive technology 2004–2013. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, B.C. Towards the global coverage of a unified registry of IVF outcomes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 38, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinborg, A.; Wennerholm, U.B.; Bergh, C. Long-term outcomes for children conceived by assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntsen, S.; Söderström-Anttila, V.; Wennerholm, U.-B.; Laivuori, H.; Loft, A.; Oldereid, N.B.; Romundstad, L.B.; Bergh, C.; Pinborg, A. The health of children conceived by ART: ‘The chicken or the egg? ’ Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, M.E.; Jelin, A.; Hoon, A.H.; Wilms Floet, A.M.; Levey, E.; Graham, E.M. Assisted reproductive technology: Short- and long-term outcomes. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2023, 65, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Reyes Palomares, A.; Iwarsson, E.; Oberg, A.S.; Rodriguez-Wallberg, K.A. Imprinting disorders in children conceived with assisted reproductive technology in Sweden. Fertil. Steril. 2024, 122, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reik, W.; Walter, J. Genomic imprinting: Parental influence on the genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001, 2, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagami, M.; Hara-Isono, K.; Sasaki, A.; Amita, M. Association between imprinting disorders and assisted reproductive technologies. Epigenomics 2025, 17, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, D.; Mackay, D.J.G.; Eggermann, T.; Maher, E.R.; Riccio, A. Genomic imprinting disorders: Lessons on how genome, epigenome and environment interact. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBaun, M.R.; Niemitz, E.L.; Feinberg, A.P. Association of In Vitro Fertilization with Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome and Epigenetic Alterations of LIT1 and H19. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicquel, C.; Gaston, V.; Mandelbaum, J.; Siffroi, J.P.; Flahault, A.; Le Bouc, Y. In Vitro Fertilization May Increase the Risk of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Related to the Abnormal Imprinting of the KCNQ1OT Gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 1338–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, E.R. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and assisted reproduction technology (ART). J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, A.G.; Peters, C.J.; Bowdin, S.; Temple, K.; Reardon, W.; Wilson, L.; Clayton-Smith, J.; Brueton, L.A.; Bannister, W.; Maher, E.R. Assisted reproductive therapies and imprinting disorders—A preliminary British survey. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 1009–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornbos, M.E.; Maas, S.M.; McDonnell, J.; Vermeiden, J.P.W.; Hennekam, R.C.M. Infertility, assisted reproduction technologies and imprinting disturbances: A Dutch study. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 2476–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiura, H.; Okae, H.; Miyauchi, N.; Sato, F.; Sato, A.; Van De Pette, M.; John, R.M.; Kagami, M.; Nakai, K.; Soejima, H.; et al. Characterization of DNA methylation errors in patients with imprinting disorders conceived by assisted reproduction technologies. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 2541–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiura, H.; Okae, H.; Chiba, H.; Miyauchi, N.; Sato, F.; Sato, A.; Arima, T. Imprinting methylation errors in ART. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2014, 13, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Seli, E. The impact of assisted reproductive technologies on genomic imprinting and imprinting disorders. Curr. Opin. Obs. Gynecol. 2014, 26, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Hood, A.; Mancuso, F.; Horan, S.; Walker, Z. Effects of Assisted Reproductive Technology on Genetics, Obstetrics, and Neonatal Outcomes. Neoreviews 2025, 26, e89–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, T. Human Reproduction and Disturbed Genomic Imprinting. Genes 2024, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, L.; Rodenhiser, D.; Siu, V.; McCready, E.; Ainsworth, P.; Sadikovic, B. Constitutional Epi/Genetic Conditions: Genetic, Epigenetic, and Environmental Factors. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2016, 6, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eggermann, T.; Monk, D.; de Nanclares, G.P.; Kagami, M.; Giabicani, E.; Riccio, A.; Tümer, Z.; Kalish, J.M.; Tauber, M.; Duis, J.; et al. Imprinting disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagar, V.; Hutchison, W.; Muscat, A.; Krishnan, A.; Hoke, D.; Buckle, A.; Siswara, P.; Amor, D.J.; Mann, J.; Pinner, J.; et al. Genetic variation affecting DNA methylation and the human imprinting disorder, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 2018, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tserga, A.; Binder, A.M.; Michels, K.B. Impact of folic acid intake during pregnancy on genomic imprinting of IGF2/H19 and 1-carbon metabolism. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 5149–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzek, A.; Knežević, J.; Switzeny, O.J.; Cooper, A.; Barić, I.; Beluzić, R.; Strauss, K.A.; Puffenberger, E.G.; Mudd, S.H.; Vugrek, O.; et al. Abnormal Hypermethylation at Imprinting Control Regions in Patients with S-Adenosylhomocysteine Hydrolase (AHCY) Deficiency. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Lim, J.; Lee, S.; Jeong, J.; Kang, H.; Kim, Y.; Kang, J.W.; Yu, H.Y.; Jeong, E.M.; Kim, K.; et al. Sirt1 Regulates DNA Methylation and Differentiation Potential of Embryonic Stem Cells by Antagonizing Dnmt3l. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 1930–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susiarjo, M.; Sasson, I.; Mesaros, C.; Bartolomei, M.S. Bisphenol A Exposure Disrupts Genomic Imprinting in the Mouse. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapphoff, T.; Heiligentag, M.; El Hajj, N.; Haaf, T.; Eichenlaub-Ritter, U. Chronic exposure to a low concentration of bisphenol A during follicle culture affects the epigenetic status of germinal vesicles and metaphase II oocytes. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 1758–1767.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, F.; Zhou, X.; Pan, H.; Li, R. Differential responses of GC-1 spermatogonia cells to high and low doses of bisphenol, A. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3034–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Isono, K.; Matsubara, K.; Nakamura, A.; Sano, S.; Inoue, T.; Kawashima, S.; Fuke, T.; Yamazawa, K.; Fukami, M.; Ogata, T.; et al. Risk Assessment of Assisted Reproductive Technology and Parental Age at Childbirth for the Development of Uniparental Disomy-Mediated Imprinting Disorders Caused by Aneuploid Gametes. Clin Epigenet. 2023, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, G.F.; Bürger, J.; Lip, V.; Mau, U.A.; Sperling, K.; Wu, B.-L.; Horsthemke, B. Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection May Increase the Risk of Imprinting Defects. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 71, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, P.J.; Jeoung, M.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, D.R.; Ko, C.; Baker, D.J. Methodology matters: IVF versus ICSI and embryonic gene expression. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2011, 23, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.; Yaba-Ucar, A.; Sozen, B.; Mutlu, D.; Demir, N. Superovulation alters embryonic poly(A)-binding protein (Epab) and poly(A)-binding protein, cytoplasmic 1 (Pabpc1) gene expression in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2016, 28, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Auwera, I. Superovulation of female mice delays embryonic and fetal development. Hum. Reprod. 2001, 16, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberet, J.; Ducreux, B.; Guilleman, M.; Simon, E.; Bruno, C.; Fauque, P. DNA methylation profiles after ART during human lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2022, 28, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfakianoudis, K.; Zikopoulos, A.; Grigoriadis, S.; Seretis, N.; Maziotis, E.; Anifandis, G.; Xystra, P.; Kostoulas, C.; Giougli, U.; Pantos, K.; et al. The Role of One-Carbon Metabolism and Methyl Donors in Medically Assisted Reproduction: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voros, C.; Varthaliti, A.; Mavrogianni, D.; Athanasiou, D.; Athanasiou, A.; Athanasiou, A.; Papahliou, A.-M.; Zografos, C.G.; Topalis, V.; Kondili, P.; et al. Epigenetic Alterations in Ovarian Function and Their Impact on Assisted Reproductive Technologies: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Otsu, E.; Negishi, H.; Utsunomiya, T.; Arima, T. Aberrant DNA methylation of imprinted loci in superovulated oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciorio, R.; Tramontano, L.; Rapalini, E.; Bellaminutti, S.; Bulletti, F.M.; D’Amato, A.; Manna, C.; Palagiano, A.; Bulletti, C.; Esteves, S.C. Risk of genetic and epigenetic alteration in children conceived following ART: Is it time to return to nature whenever possible? Clin. Genet. 2023, 103, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, E. Alteration of Genomic Imprinting after Assisted Reproductive Technologies and Long-Term Health. Life 2021, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.; Norman, R.J. The longer-term health outcomes for children born as a result of IVF treatment: Part I—General health outcomes. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciorio, R.; Esteves, S.C. Contemporary Use of ICSI and Epigenetic Risks to Future Generations. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, H.; Hiura, H.; Kitamura, A.; Miyauchi, N.; Kobayashi, N.; Takahashi, S.; Okae, H.; Kyono, K.; Kagami, M.; Ogata, T.; et al. Association of four imprinting disorders and ART. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, S.C.; Roque, M.; Bedoschi, G.; Haahr, T.; Humaidan, P. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection for male infertility and consequences for offspring. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, F.; Kahveci, S.; Sukur, G.; Cinar, O. Embryo culture media differentially alter DNA methylating enzymes and global DNA methylation in embryos and oocytes. J. Mol. Histol. 2022, 53, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasterstein, E.; Strassburger, D.; Komarovsky, D.; Bern, O.; Komsky, A.; Raziel, A.; Friedler, S.; Ron-El, R. The effect of two distinct levels of oxygen concentration on embryo development in a sibling oocyte study. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2013, 30, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciorio, R.; Tramontano, L.; Gullo, G.; Fleming, S. Association Between Human Embryo Culture Conditions, Cryopreservation, and the Potential Risk of Birth Defects in Children Conceived Through Assisted Reproduction Technology. Medicina 2025, 61, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, C.; Esteves, T.C.; Arauzo-Bravo, M.J.; Le Gac, S.; Nordhoff, V.; Schlatt, S.; Boiani, M. ART culture conditions change the probability of mouse embryo gestation through defined cellular and molecular responses. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 2627–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijkers, S.H.M.; Eijssen, L.M.T.; Coonen, E.; Derhaag, J.G.; Mantikou, E.; Jonker, M.J.; Mastenbroek, S.; Repping, S.; Evers, J.L.H.; Dumoulin, J.C.M.; et al. Differences in gene expression profiles between human preimplantation embryos cultured in two different IVF culture media. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 2303–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsen, A.A.; Gissler, M.; Rasmussen, S.; Opdahl, S.; Wennerholm, U.B.; Spangmose, A.L.; Tiitinen, A.; Bergh, C.; Romundstad, L.B.; Laivuori, H.; et al. Imprinting disorders in children born after ART: A Nordic study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Barberet, J.; Binquet, C.; Guilleman, M.; Doukani, A.; Choux, C.; Bruno, C.; Bourredjem, A.; Chapusot, C.; Bourc’his, D.; Duffourd, Y.; et al. Do assisted reproductive technologies and in vitro embryo culture influence the epigenetic control of imprinted genes and transposable elements in children? Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.L.; Wattimury, T.M.; Jongejan, A.; de Winter-Korver, C.M.; van Daalen, S.K.M.; Struijk, R.B.; Borgman, S.C.M.; Wurth, Y.; Consten, D.; van Echten-Arends, J.; et al. Comparison of DNA methylation patterns of parentally imprinted genes in placenta derived from IVF conceptions in two different culture media. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, N.J.; Waterland, R.A.; Prentice, A.M.; Silver, M.J. Establishment of environmentally sensitive DNA methylation states in the very early human embryo. Sci Adv. 2018, 4, eaat2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciorio, R.; Cantatore, C.; D’Amato, G.; Smith, G.D. Cryopreservation, cryoprotectants, and potential risk of epigenetic alteration. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024, 41, 2953–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.G.; Curtis Johnson, W. Conformation of DNA in ethylene glycol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1970, 41, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.-Y.; Zhang, S.-W.; Wu, H.-Y.; Mo, J.-Y.; Yu, J.-E.; He, R.-K.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Zhu, K.-J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Lin, Z.-L.; et al. Safety of embryo cryopreservation: Insights from mid-term placental transcriptional changes. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2024, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Aghebati-Maleki, L.; Rashidiani, S.; Csabai, T.; Nnaemeka, O.B.; Szekeres-Bartho, J. Long-Term Effects of ART on the Health of the Offspring. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, E.; Vrooman, L.A.; Fischer, E.; Ord, T.; Mainigi, M.A.; Coutifaris, C.; Schultz, R.M.; Bartolomei, M.S. The Cumulative Effect of Assisted Reproduction Procedures on Placental Development and Epigenetic Perturbations in a Mouse Model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 6975–6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A.; Russo, S.; De Crescenzo, A.; Chiesa, N.; Molinatto, C.; Selicorni, A.; Richiardi, L.; Larizza, L.; Silengo, M.C.; Riccio, A.; et al. Prevalence of beckwith–wiedemann syndrome in North West of Italy. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2013, 161, 2481–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Kirby, G.; Hardy, C.; Dias, R.P.; Tee, L.; Lim, D.; Berg, J.; MacDonald, F.; Nightingale, P.; Maher, E.R. Methylation analysis and diagnostics of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome in 1,000 subjects. Clin. Epigenet. 2014, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzin, A.; Carli, D.; Sirchia, F.; Molinatto, C.; Cardaropoli, S.; Palumbo, G.; Zampino, G.; Ferrero, G.B.; Mussa, A. Phenotype evolution and health issues of adults with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2019, 179, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A.; Peruzzi, L.; Chiesa, N.; De Crescenzo, A.; Russo, S.; Melis, D.; Tarani, L.; Baldassarre, G.; Larizza, L.; Riccio, A.; et al. Nephrological findings and genotype–phenotype correlation in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2012, 27, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brioude, F.; Kalish, J.M.; Mussa, A.; Foster, A.C.; Bliek, J.; Ferrero, G.B.; Boonen, S.E.; Cole, T.; Baker, R.; Bertoletti, M.; et al. Clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: An international consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A.; Russo, S.; Larizza, L.; Riccio, A.; Ferrero, G.B. (Epi)genotype–phenotype correlations in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: A paradigm for genomic medicine. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, K.A.; Cielo, C.M.; Cohen, J.L.; Gonzalez-Gandolfi, C.X.; Griff, J.R.; Hathaway, E.R.; Kupa, J.; Taylor, J.A.; Wang, K.H.; Ganguly, A.; et al. Characterization of the Beckwith-Wiedemann spectrum: Diagnosis and management. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidegaard, Ø.; Pinborg, A.; Andersen, A.N. Imprinting diseases and IVF: Danish National IVF cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 950–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Isono, K.; Matsubara, K.; Mikami, M.; Arima, T.; Ogata, T.; Fukami, M.; Kagami, M. Assisted reproductive technology represents a possible risk factor for development of epimutation-mediated imprinting disorders for mothers aged ≥ 30 years. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussa, A.; Molinatto, C.; Cerrato, F.; Palumbo, O.; Carella, M.; Baldassarre, G.; Carli, D.; Peris, C.; Riccio, A.; Ferrero, G.B. Assisted Reproductive Techniques and Risk of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20164311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Bowdin, S.C.; Tee, L.; Kirby, G.A.; Blair, E.; Fryer, A.; Lam, W.; Oley, C.; Cole, T.; Brueton, L.A.; et al. Clinical and molecular genetic features of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome associated with assisted reproductive technologies. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 24, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, J.; Romanelli, V.; Martin-Trujillo, A.; Fernández, G.; Segovia, M.; Perandones, C.; Pérez Jurado, L.A.; Esteller, M.; Fraga, M.; Arias, P.; et al. Clinical and molecular analyses of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: Comparison between spontaneous conception and assisted reproduction techniques. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 2740–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, D.; Operti, M.; Russo, S.; Cocchi, G.; Milani, D.; Leoni, C.; Prada, E.; Melis, D.; Falco, M.; Spina, J.; et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients affected by Beckwith-Wiedemann spectrum conceived through assisted reproduction techniques. Clin. Genet. 2022, 102, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, A.; Martini, A.; Owen, C. Assisted Reproductive Technology and Epigenetics. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2018, 36, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buiting, K. Prader–Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2010, 154, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalande, M.; Calciano, M.A. Molecular epigenetics of Angelman syndrome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.A.; Driscoll, D.J.; Dagli, A.I. Clinical and genetic aspects of Angelman syndrome. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.D.; Knepper, J.L. Genome Organization, Function, and Imprinting in Prader-Willi and Angelman Syndromes. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2001, 2, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, M. Increased prevalence of imprinting defects in patients with Angelman syndrome born to subfertile couples. J. Med. Genet. 2005, 42, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Prader-Willi, M. Syndrome: Obesity due to Genomic Imprinting. Curr. Genom. 2011, 12, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, S.B.; Driscoll, D.J. Prader–Willi syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 17, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotto, M.; Gambadauro, A.; Rocchi, A.; Lelii, M.; Madini, B.; Cerrato, L.; Chironi, F.; Belhaj, Y.; Patria, M.F. Pediatric Sleep Respiratory Disorders: A Narrative Review of Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Children 2023, 10, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horánszky, A.; Becker, J.L.; Zana, M.; Ferguson-Smith, A.C.; Dinnyés, A. Epigenetic Mechanisms of ART-Related Imprinting Disorders: Lessons From iPSC and Mouse Models. Genes 2021, 12, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.-A.; Ruth, C.; Osann, K.; Flodman, P.; McManus, B.; Lee, H.-S.; Donkervoort, S.; Khare, M.; Roof, E.; Dykens, E.; et al. Frequency of Prader–Willi syndrome in births conceived via assisted reproductive technology. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wakeling, E.L.; Brioude, F.; Lokulo-Sodipe, O.; O’Connell, S.M.; Salem, J.; Bliek, J.; Canton, A.P.M.; Chrzanowska, K.H.; Davies, J.H.; Dias, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Silver–Russell syndrome: First international consensus statement. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermann, T. Russell–Silver syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2010, 154, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Amero, S.; Monk, D.; Frost, J.; Preece, M.; Stanier, P.; Moore, G.E. The genetic aetiology of Silver-Russell syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2007, 45, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagami, M.; Nagai, T.; Fukami, M.; Yamazawa, K.; Ogata, T. Silver-Russell syndrome in a girl born after in vitro fertilization: Partial hypermethylation at the differentially methylated region of PEG1/MEST. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2007, 24, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Uk, A.; Collardeau-Frachon, S.; Scanvion, Q.; Michon, L.; Amar, E. Assisted Reproductive Technologies and imprinting disorders: Results of a study from a French congenital malformations registry. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 61, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortessis, V.K.; Azadian, M.; Buxbaum, J.; Sanogo, F.; Song, A.Y.; Sriprasert, I.; Wei, P.C.; Yu, J.; Chung, K.; Siegmund, K.D. Comprehensive meta-analysis reveals association between multiple imprinting disorders and conception by assisted reproductive technology. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bens, S.; Kolarova, J.; Beygo, J.; Buiting, K.; Caliebe, A.; Eggermann, T.; Gillessen-Kaesbach, G.; Prawitt, D.; Thiele-Schmitz, S.; Begemann, M.; et al. Phenotypic Spectrum and Extent of DNA Methylation Defects Associated with Multilocus Imprinting Disturbances. Epigenomics 2016, 8, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Bedeschi, M.F.; Maitz, S.; Cereda, A.; Faré, C.; Motta, S.; Seresini, A.; D’Ursi, P.; Orro, A.; Pecile, V.; et al. Characterization of multi-locus imprinting disturbances and underlying genetic defects in patients with chromosome 11p15.5 related imprinting disorders. Epigenetics 2018, 13, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzi, S.; Rossignol, S.; Steunou, V.; Sas, T.; Thibaud, N.; Danton, F.; Le Jule, M.; Heinrichs, C.; Cabrol, S.; Gicquel, C.; et al. Multilocus methylation analysis in a large cohort of 11p15-related foetal growth disorders (Russell Silver and Beckwith Wiedemann syndromes) reveals simultaneous loss of methylation at paternal and maternal imprinted loci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 4724–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakawa, T.; Soejima, H.; Yamoto, K.; Hara-Isono, K.; Nakamura, A.; Kawashima, S.; Narusawa, H.; Kosaki, R.; Nishimura, Y.; Yamazawa, K.; et al. Comprehensive molecular and clinical findings in 29 patients with multi-locus imprinting disturbance. Clin. Epigenet. 2024, 16, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilo, L.; Ochoa, E.; Lee, S.; Dey, D.; Kurth, I.; Kraft, F.; Rodger, F.; Docquier, F.; Toribio, A.; Bottolo, L.; et al. Molecular characterisation of 36 multilocus imprinting disturbance (MLID) patients: A comprehensive approach. Clin. Epigenet. 2023, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Tabano, S.; Maitz, S.; Colapietro, P.; Garzia, E.; Gerli, A.G.; Sirchia, S.M.; Miozzo, M. Clinical and Molecular Diagnosis of Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome with Single- or Multi-Locus Imprinting Disturbance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesahat, F.; Montazeri, F.; Hoseini, S.M. Preimplantation genetic testing in assisted reproduction technology. J. Gynecol. Obs. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufke, A.; Eggermann, T.; Kagan, K.O.; Hoopmann, M.; Elbracht, M. Prenatal testing for Imprinting Disorders: A clinical perspective. Prenat. Diagn. 2023, 43, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, D.; Bertola, C.; Cardaropoli, S.; Ciuffreda, V.P.; Pieretto, M.; Ferrero, G.B.; Mussa, A. Prenatal features in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and indications for prenatal testing. J. Med. Genet. 2021, 58, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzi, S.; Salem, J.; Thibaud, N.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Lieber, E.; Netchine, I.; Harbison, M.D. A prospective study validating a clinical scoring system and demonstrating phenotypical-genotypical correlations in Silver-Russell syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2015, 52, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Jing, X.Y.; Wan, J.H.; Pan, M.; Li, D.Z. Prenatal Silver-Russell Syndrome in a Chinese Family Identified by Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing. Mol. Syndromol. 2022, 13, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wax, J.R.; Burroughs, R.; Wright, M.S. Prenatal sonographic features of Russell-Silver syndrome. J. Ultrasound Med. 1996, 15, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkert, A.; Dittmann, K.; Seelbach-Göbel, B. Silver-Russell syndrome as a cause for early intrauterine growth restriction. Prenat. Diagn. 2005, 25, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, Y.; Lokulo-Sodipe, K.; Mackay, D.J.G.; Davies, J.H.; Temple, I.K. Temple syndrome: Improving the recognition of an underdiagnosed chromosome 14 imprinting disorder: An analysis of 51 published cases. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 51, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, S.; Jia, B.; Wu, R.; Chang, Q. Prenatal Diagnosis of a Mosaic Paternal Uniparental Disomy for Chromosome 14: A Case Report of Kagami–Ogata Syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2021, 9, 691761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, A.P.; Holland, A.J.; Hauffa, B.P.; Hokken-Koelega, A.C.; Tauber, M. Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Management of Prader-Willi Syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 4183–4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, L. Angelman syndrome: Review of clinical and molecular aspects. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2014, 7, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceelen, M.; van Weissenbruch, M.M.; Roos, J.C.; Vermeiden, J.P.W.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Delemarre-van de Waal, H.A. Body Composition in Children and Adolescents Born after in Vitro Fertilization or Spontaneous Conception. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 3417–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Pyke, C.S.; Senapati, S.; Mainigi, M.A.; Barnhart, K.T. In Vitro fertilization and adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceelen, M.; van Weissenbruch, M.M.; Vermeiden, J.P.W.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Delemarre-van de Waal, H.A. Cardiometabolic Differences in Children Born After in Vitro Fertilization: Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, U.; Rimoldi, S.F.; Rexhaj, E.; Stuber, T.; Duplain, H.; Garcin, S.; de Marchi, S.F.; Nicod, P.; Germond, M.; Allemann, Y.; et al. Systemic and Pulmonary Vascular Dysfunction in Children Conceived by Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Circulation 2012, 125, 1890–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Lv, P.-P.; Ding, G.-L.; Yu, T.-T.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Hu, X.-L.; Lin, X.-H.; Tian, S.; Lv, M.; et al. High Maternal Serum Estradiol Levels Induce Dyslipidemia in Human Newborns via a Hepatic HMGCR Estrogen Response Element. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, S.D.; Loutradis, D.; Kanaka-Gantenbein, C.; Margeli, A.; Papastamataki, M.; Papassotiriou, I.; Chrousos, G.P. Absence of insulin resistance and low-grade inflammation despite early metabolic syndrome manifestations in children born after in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1693–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balayla, J.; Sheehy, O.; Fraser, W.D.; Séguin, J.R.; Trasler, J.; Monnier, P.; MacLeod, A.A.; Simard, M.-N.; Muckle, G.; Bérard, A. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes After Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, B.; Dahlquist, G.; Ericson, A.; Finnström, O.; Köster, M.; Stjernqvist, K. Neurological sequelae in children born after in-vitro fertilisation: A population-based study. Lancet 2002, 359, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.L.; Hvidtjorn, D.; Basso, O.; Obel, C.; Thorsen, P.; Uldall, P.; Olsen, J. Parental infertility and cerebral palsy in children. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 3142–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuwantono, T.; Aviani, J.K.; Permadi, W.; Achmad, T.H.; Halim, D. Risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in children born from different ART treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2020, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissin, D.M.; Zhang, Y.; Boulet, S.L.; Fountain, C.; Bearman, P.; Schieve, L.; Yeargin-Allsopp, M.; Jamieson, D.J. Association of assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment and parental infertility diagnosis with autism in ART-conceived children. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, T.G.; Aston, K.I.; Pflueger, C.; Cairns, B.R.; Carrell, D.T. Age-Associated Sperm DNA Methylation Alterations: Possible Implications in Offspring Disease Susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.K.; Ratcliffe, S.J.; Coutifaris, C.; Molinaro, T.; Barnhart, K.T. Ovarian Stimulation and Low Birth Weight in Newborns Conceived Through In Vitro Fertilization. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 118, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, A.; Raja, E.A.; Bhattacharya, S. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes after either fresh or thawed frozen embryo transfer: An analysis of 112,432 singleton pregnancies recorded in the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority anonymized dataset. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Syndrome (Acronym) | Incidence (General Population) | Incidence (ART-Conceived) | Clinical Features | Prenatal Findings | Genetic/ Epigenetic Mechanisms | ART Association | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beckwith–Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS) | ~1:10,340 | 4–15%; up to 10× increased risk | Macrosomia, macroglossia, omphalocele, visceromegaly, hypoglycemia, Wilms tumor risk | Fetal overgrowth, omphalocele, placentomegaly, mesenchymal dysplasia | ICR2 hypomethylation (50%), paternal UPD11 (20%), ICR1 GOM, CDKN1C mutations | Strong, especially with ICSI and cryopreservation | [30,31,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] |

| Silver–Russell Syndrome (SRS) | 1:30,000–1:100,000 | Up to 10× higher in some ART cohorts | IUGR, postnatal growth delay, triangular face, body asymmetry | IUGR, macrocephaly, facial dysmorphism | 11p15.5 H19/IGF2 hypomethylation (30–60%), maternal UPD7 (5–10%) | Strong; especially linked to methylation errors | [15,50,56,57,58,59,60] |

| Angelman Syndrome (AS) | ~1:15,000 | ~2× risk in ART-treated subfertile couples | Severe developmental delay, ataxia, speech impairment, happy demeanor | Not specific | UBE3A loss (maternal), deletions (65–75%), UPD, epimutations | Controversial; ART-related SNRPN hypomethylation | [28,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Prader–Willi Syndrome (PWS) | 1:15,000–1:30,000 | Mixed; up to 3.4× higher in some populations | Hypotonia, poor sucking, obesity, ID, hypogonadism, behavior issues | Reduced fetal movements, polyhydramnios | Paternal deletion (65–75%), maternal UPD (20–30%), ICR defects | Variable; possible link with maternal age, methylation errors | [30,50,51,52,53,54,55] |

| Temple Syndrome (TS14) | Very rare | Limited data | IUGR, neonatal hypotonia, truncal obesity, early puberty | Oligohydramnios, small placenta, IUGR | Maternal UPD14, LOM at MEG3/DLK1:IG-DMR | Plausible by a specific mechanism | [8,18,68] |

| Kagami–Ogata Syndrome (KOS14) | Very rare | Limited data | Polyhydramnios, respiratory failure, omphalocele, narrow thorax | Polyhydramnios, abdominal wall defects, narrow thorax | Paternal UPD14, GOM at MEG3/DLK1:IG-DMR, maternal deletions | Plausible by a specific mechanism | [8,18,69] |

| Transient Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus (TNDM) | Very rare | Sparse data | Hyperglycemia, low birth weight, macroglossia, abdominal wall defects | IUGR, macroglossia, abdominal wall defect | Paternal UPD6, LOM at PLAGL1-DMR | Insufficient data | [8,13,18] |

| Pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP) | Rare | Limited data | PTH resistance, AHO features | Macrosomia (PHP1B), IUGR (PHP1A) | LOM at GNAS locus on chr20 | Plausible epigenetic link | [8,18] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gambadauro, A.; Chirico, V.; Galletta, F.; Gulino, F.; Chimenz, R.; Serraino, G.; Rulli, I.; Manganaro, A.; Gitto, E.; Marseglia, L. Imprinting Disorders and Epigenetic Alterations in Children Conceived by Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Mechanisms, Clinical Outcomes, and Prenatal Diagnosis. Genes 2025, 16, 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101242

Gambadauro A, Chirico V, Galletta F, Gulino F, Chimenz R, Serraino G, Rulli I, Manganaro A, Gitto E, Marseglia L. Imprinting Disorders and Epigenetic Alterations in Children Conceived by Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Mechanisms, Clinical Outcomes, and Prenatal Diagnosis. Genes. 2025; 16(10):1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101242

Chicago/Turabian StyleGambadauro, Antonella, Valeria Chirico, Francesca Galletta, Ferdinando Gulino, Roberto Chimenz, Giorgia Serraino, Immacolata Rulli, Alessandro Manganaro, Eloisa Gitto, and Lucia Marseglia. 2025. "Imprinting Disorders and Epigenetic Alterations in Children Conceived by Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Mechanisms, Clinical Outcomes, and Prenatal Diagnosis" Genes 16, no. 10: 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101242

APA StyleGambadauro, A., Chirico, V., Galletta, F., Gulino, F., Chimenz, R., Serraino, G., Rulli, I., Manganaro, A., Gitto, E., & Marseglia, L. (2025). Imprinting Disorders and Epigenetic Alterations in Children Conceived by Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Mechanisms, Clinical Outcomes, and Prenatal Diagnosis. Genes, 16(10), 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes16101242