SOX11 Is Regulated by EGFR-STAT3 and Promotes Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.3. Western Blotting

2.4. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

2.5. Luciferase Reporter Assay

2.6. Capillary Electrophoresis-Based Mobility Shift Assay (CEMSA)

2.7. Gene Silencing with siRNA

2.8. Plasmids and Gene Overexpression

2.9. Xenograft Mouse Model

2.10. Correlation Gene Expression Analysis of Sox11 with EMT-Related Genes in HNSCC

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

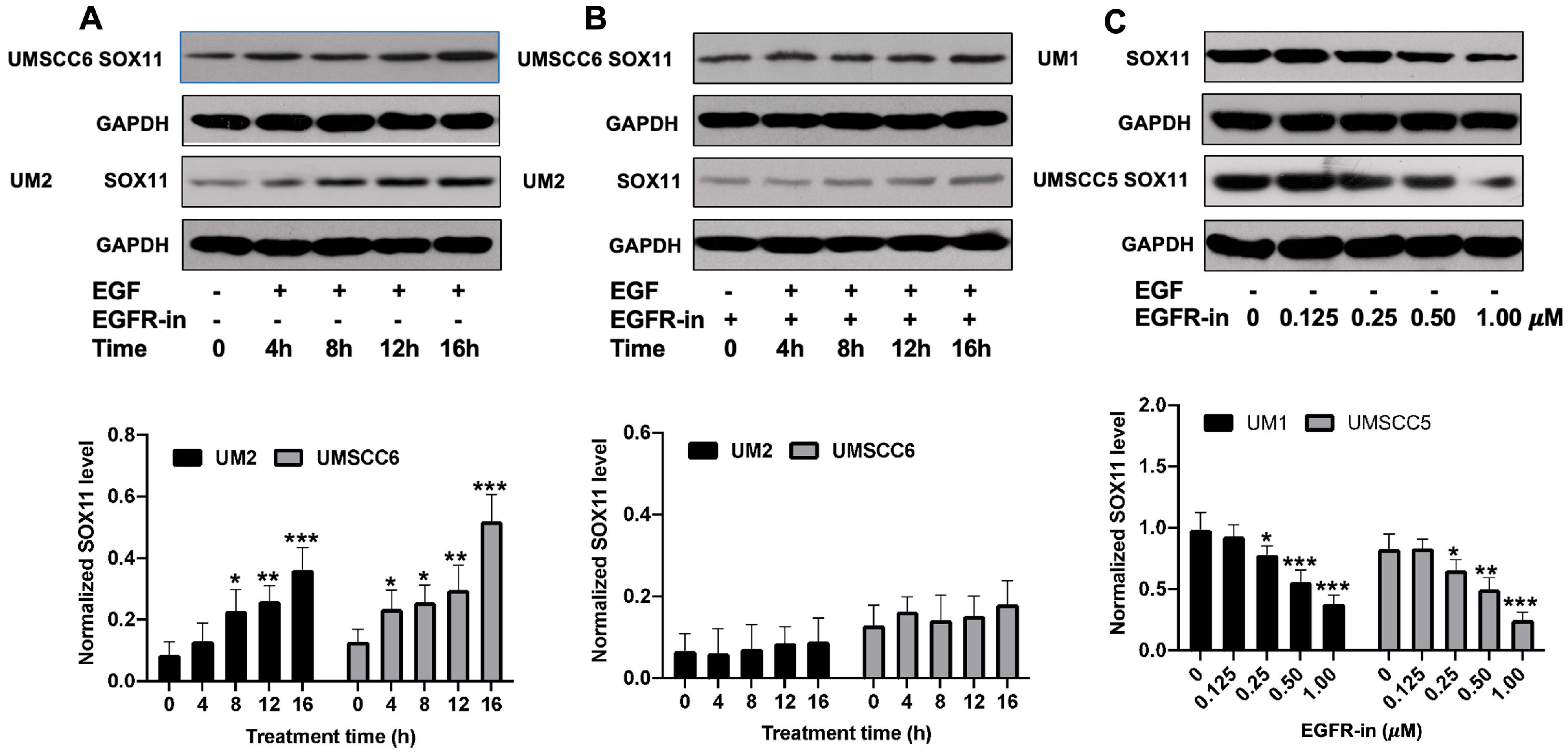

3.1. EGF Upregulates the Expression of SOX11 in HNSCC Cells

3.2. EGFR Inhibitor Suppresses the Expression of SOX11 in HNSCC Cells

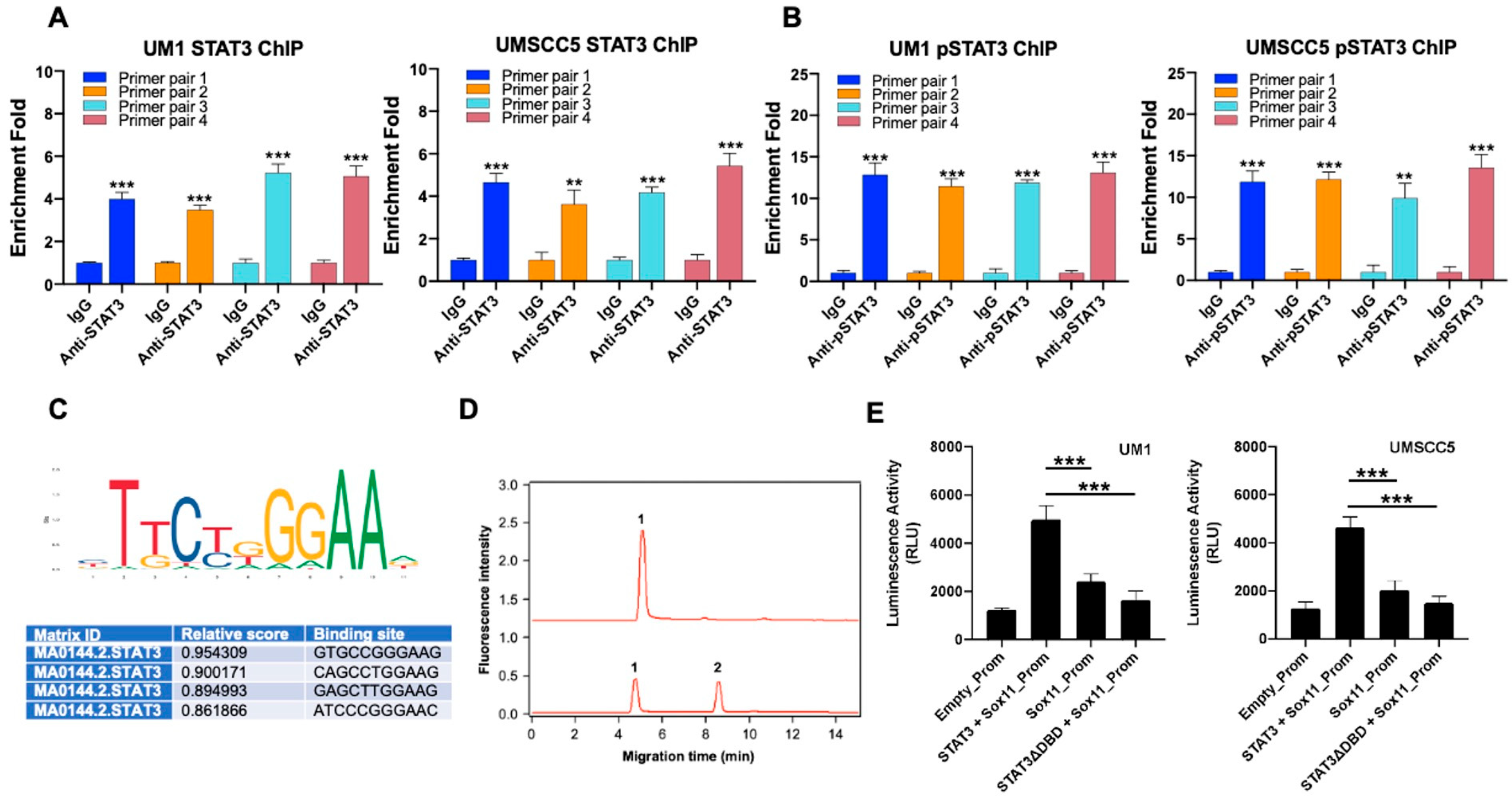

3.3. Sox11 Is Regulated by STAT3 in HNSCC Cells

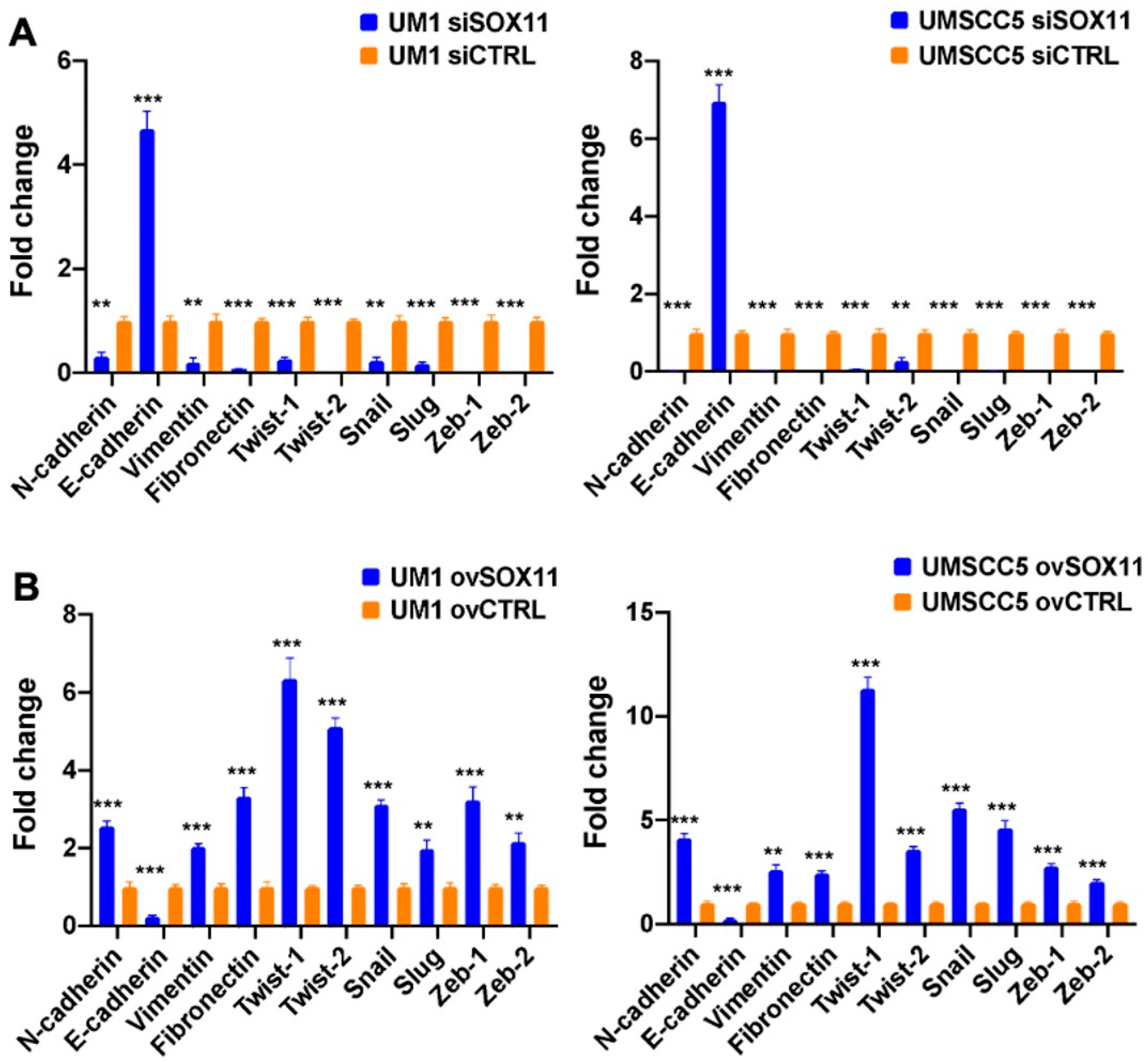

3.4. SOX11 Upregulates EMT Transcription Factors (EMT-TFs), Vimentin, Fibronectin, and N-Cadherin While It Downregulates E-Cadherin in HNSCC Cells

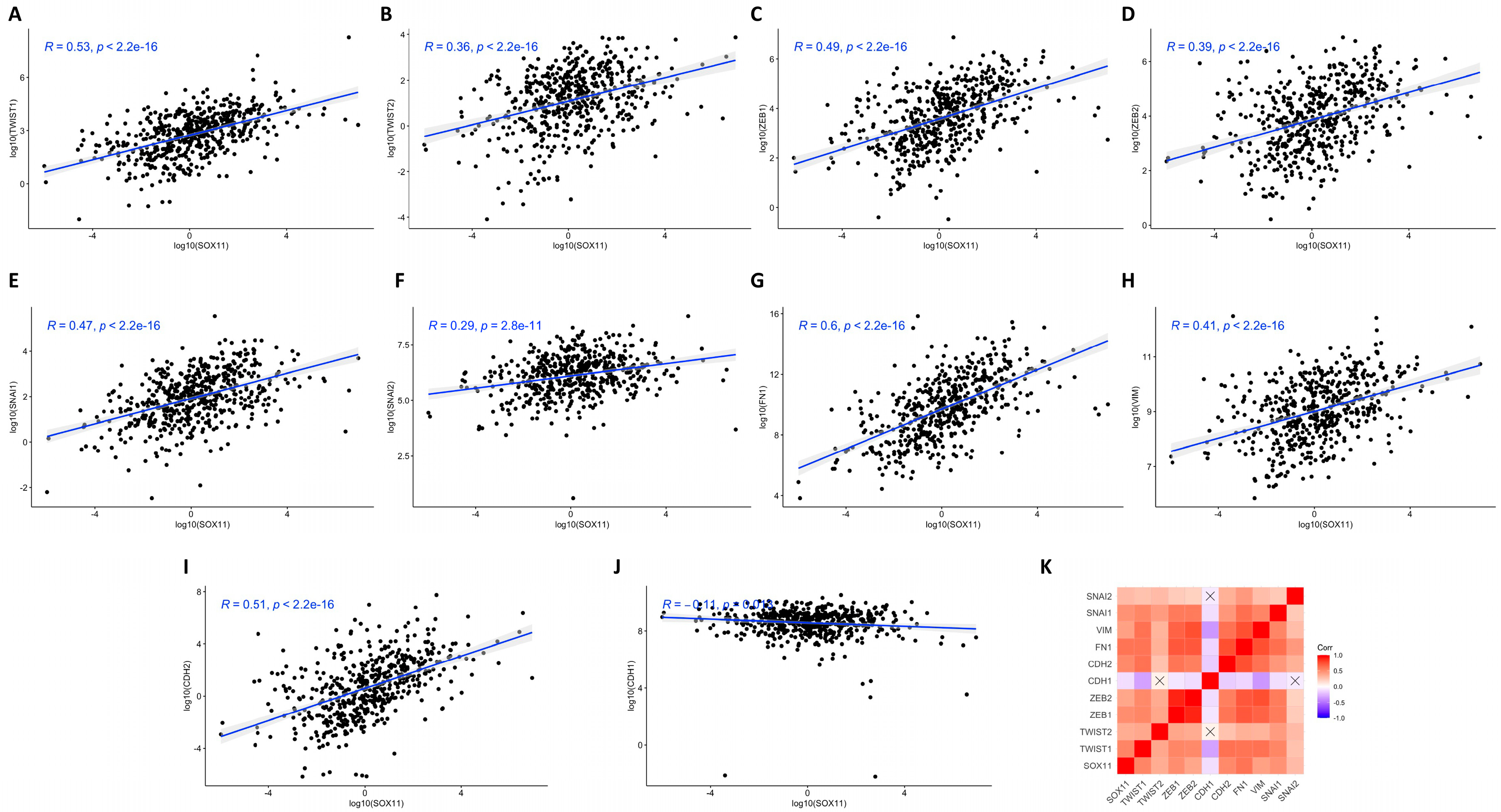

3.5. Correlation Analysis of Sox11 Gene Expression with EMT-TFs, Vimentin, Fibronectin, N-Cadherin, and E-Cadherin Expression in HNSCC Tissues

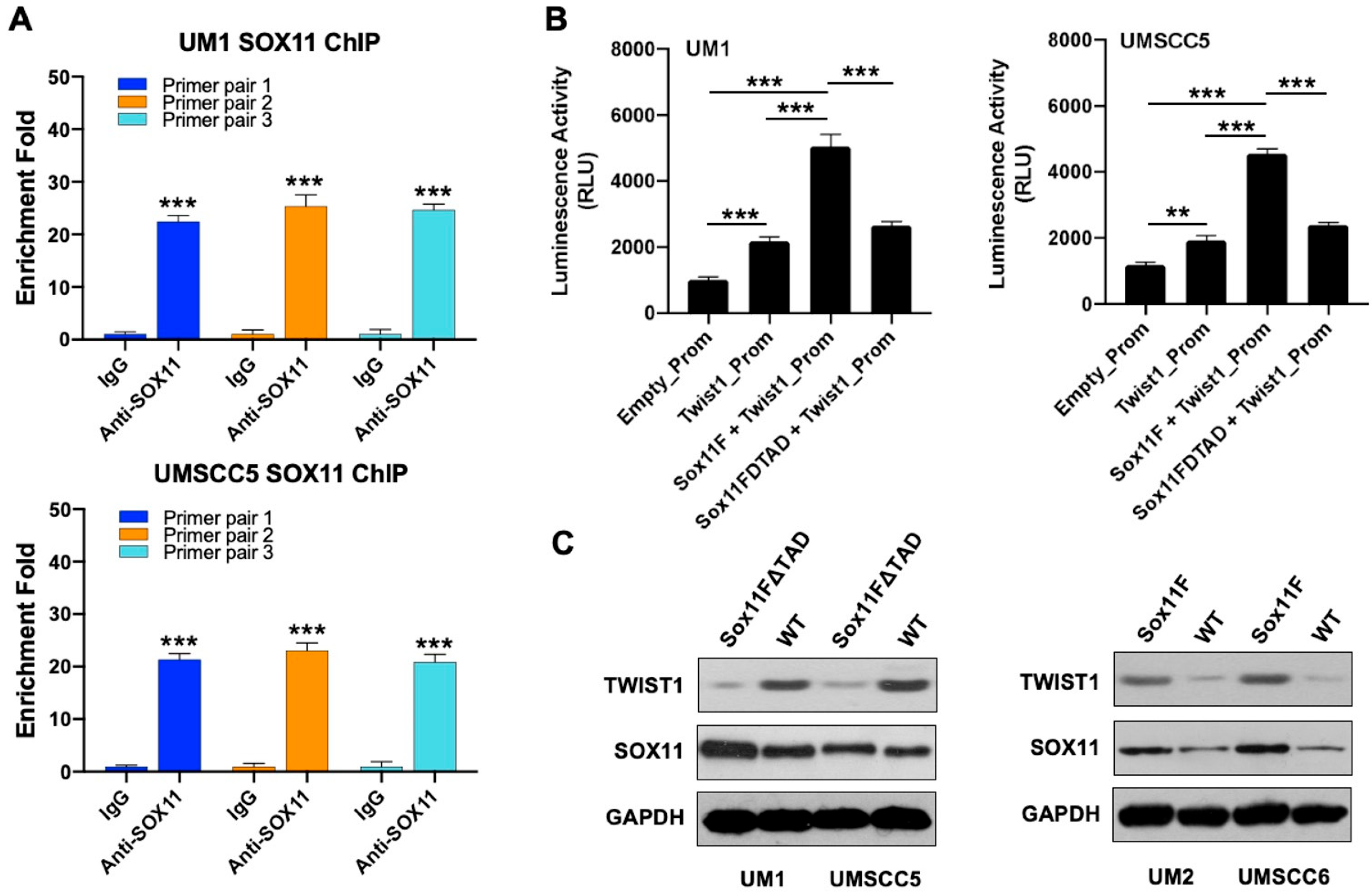

3.6. SOX11 Regulates the Expression of TWIST1 in HNSCC Cells

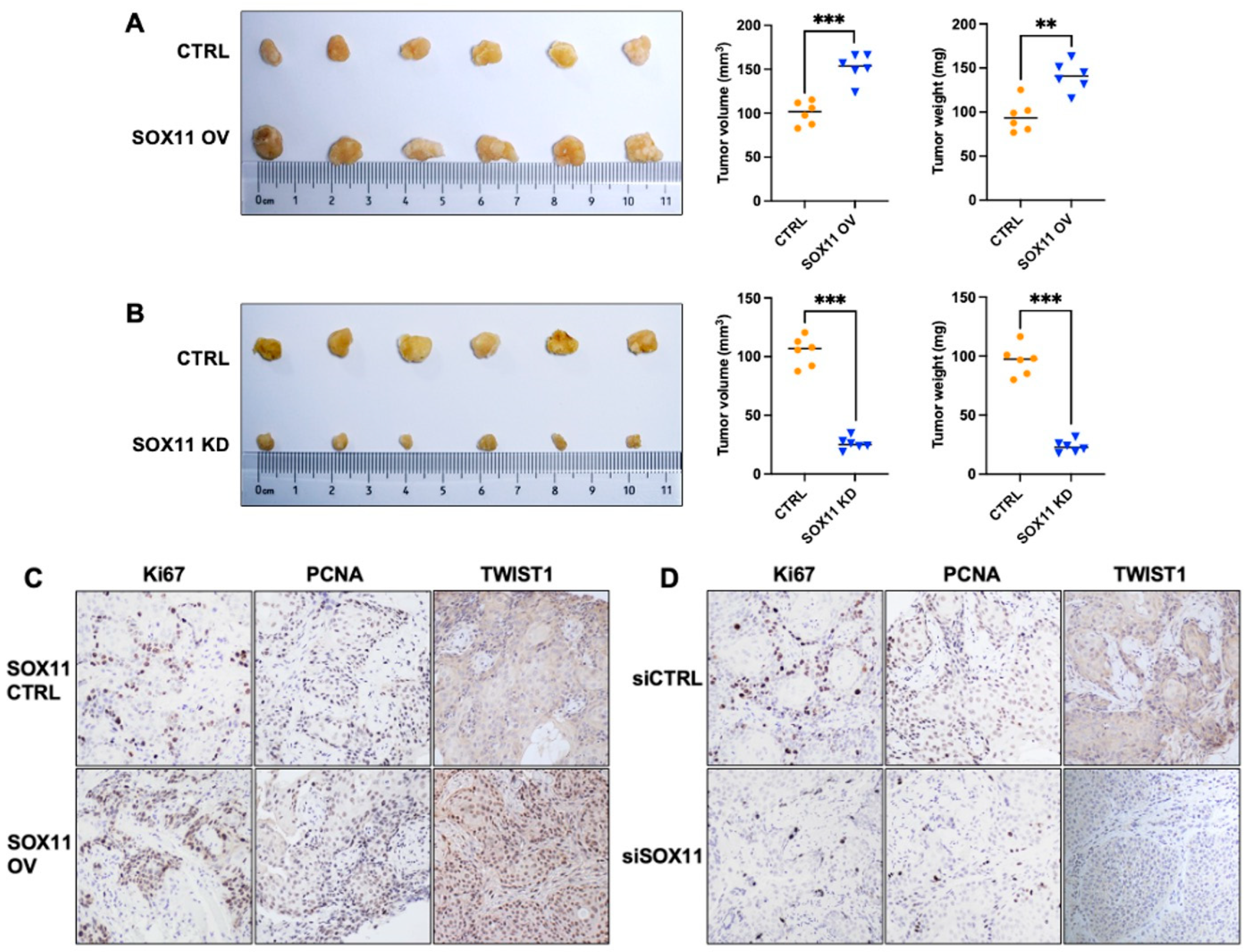

3.7. SOX11 Promotes Tumor Growth In Vivo

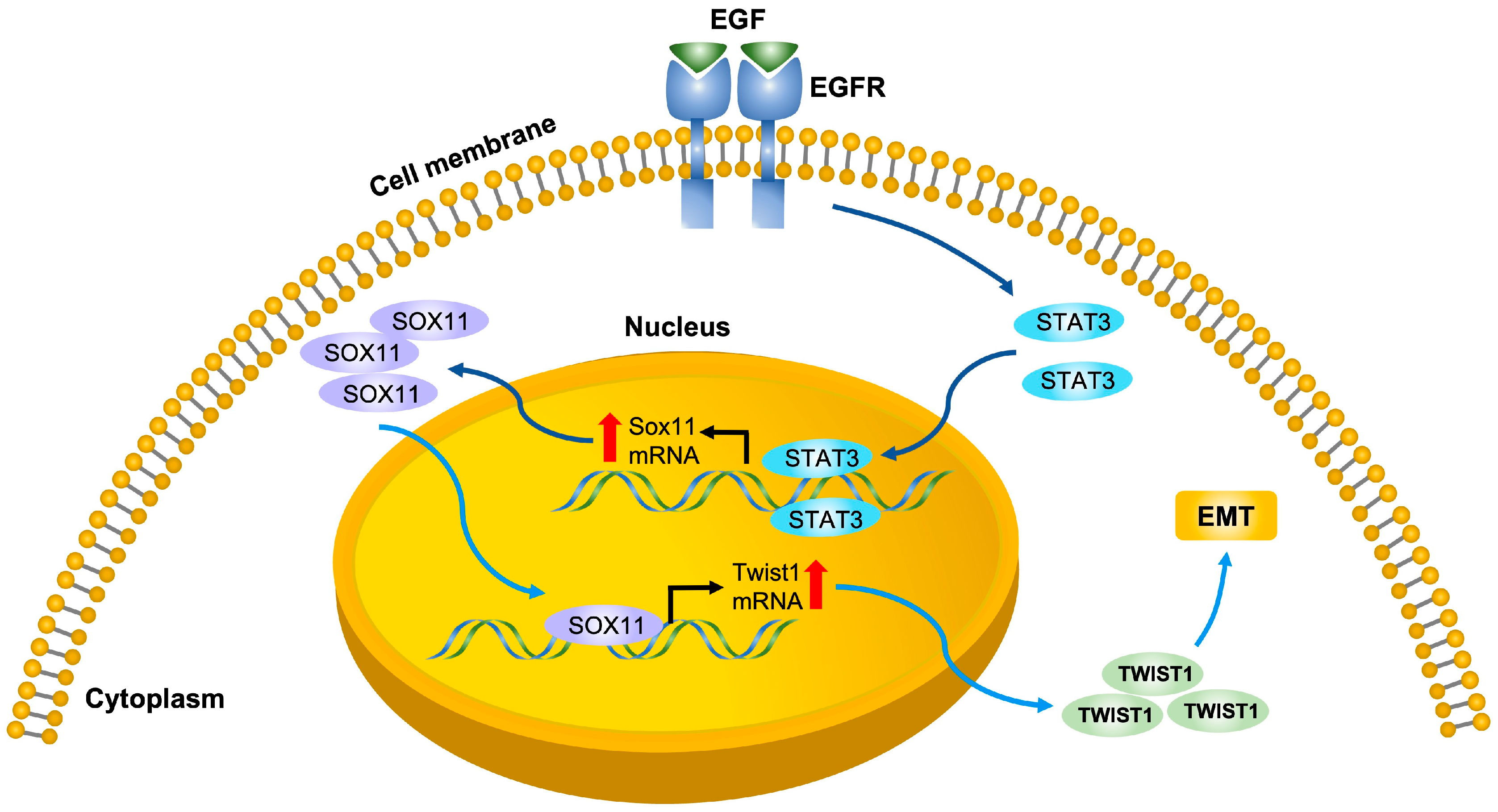

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ChIP | Chromatin immunoprecipitation |

| CEMSA | Capillary electrophoresis mobility shift assay |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EGFR-in | EGFR inhibitor |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EMEQA | N-(3-ethynylphenyl)-6,7-bis(2-methoxyethoxy)-4-quinazolinamine |

| EMT-TFs | EMT transcription factors |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| HMG | High-mobility group |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| SRY | Sex-determining region Y |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Mathers, C.; Parkin, D.M.; Pineros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Cuaran, S.; Bouaoud, J.; Karabajakian, A.; Fayette, J.; Saintigny, P. Precision Medicine Approaches to Overcome Resistance to Therapy in Head and Neck Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 614332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.H.; Berta, P.; Palmer, M.S.; Hawkins, J.R.; Griffiths, B.L.; Smith, M.J.; Foster, J.W.; Frischauf, A.M.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Goodfellow, P.N. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature 1990, 346, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, Z.Y.; Yang, W.X. SOX family transcription factors involved in diverse cellular events during development. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 94, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbay, J.; Collignon, J.; Koopman, P.; Capel, B.; Economou, A.; Munsterberg, A.; Vivian, N.; Goodfellow, P.; Lovell-Badge, R. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature 1990, 346, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Du, X.; Li, X.; Qu, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X. Genome-wide identification and transcriptome-based expression analysis of sox gene family in the Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2018, 36, 1731–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Hou, C.C.; She, Z.Y.; Yang, W.X. The SOX gene family: Function and regulation in testis determination and male fertility maintenance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 2187–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevanovic, M.; Drakulic, D.; Lazic, A.; Ninkovic, D.S.; Schwirtlich, M.; Mojsin, M. SOX Transcription Factors as Important Regulators of Neuronal and Glial Differentiation During Nervous System Development and Adult Neurogenesis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 654031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, M. From head to toes: The multiple facets of Sox proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigle, B.; Ebner, R.; Temme, A.; Schwind, S.; Schmitz, M.; Kiessling, A.; Rieger, M.A.; Schackert, G.; Schackert, H.K.; Rieber, E.P. Highly specific overexpression of the transcription factor SOX11 in human malignant gliomas. Oncol. Rep. 2005, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bont, J.M.; Kros, J.M.; Passier, M.M.; Reddingius, R.E.; Sillevis Smitt, P.A.; Luider, T.M.; den Boer, M.L.; Pieters, R. Differential expression and prognostic significance of SOX genes in pediatric medulloblastoma and ependymoma identified by microarray analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2008, 10, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, A.M.; Lord, M.; Wang, X.; Zong, F.; Andersson, P.; Kimby, E.; Christensson, B.; Karimi, M.; Sander, B. SOXC transcription factors in mantle cell lymphoma: The role of promoter methylation in SOX11 expression. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sernbo, S.; Gustavsson, E.; Brennan, D.J.; Gallagher, W.M.; Rexhepaj, E.; Rydnert, F.; Jirström, K.; Borrebaeck, C.A.K.; Ek, S. The tumour suppressor SOX11 is associated with improved survival among high grade epithelial ovarian cancers and is regulated by reversible promoter methylation. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, J.H.; Uray, I.P.; Mazumdar, A.; Tsimelzon, A.; Savage, M.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Brown, P.H. The SOX11 transcription factor is a critical regulator of basal-like breast cancer growth, invasion, and basal-like gene expression. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 13106–13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Deng, P.; Zhu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Dai, D. Aberrant SOX11 promoter methylation is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Cell. Oncol. 2015, 38, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Huang, S.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ni, M.; Meng, F.; Wang, K.; Rui, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, G. Sox11-modified mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) accelerate bone fracture healing: Sox11 regulates differentiation and migration of MSCs. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, P.; Palomero, J.; Eguileor, Á.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Vegliante, M.C.; Planas-Rigol, E.; Sureda-Gómez, M.; Cid, M.C.; Campo, E.; Amador, V. SOX11 promotes tumor protective microenvironment interactions through CXCR4 and FAK regulation in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2017, 130, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, S.D.; Matheu, A.; Mariani, N.; Carretero, J.; Lopez-Rios, F.; Lovell-Badge, R.; Sanchez-Cespedes, M. Novel transcriptional targets of the SRY-HMG box transcription factor SOX4 link its expression to the development of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dictor, M.; Ek, S.; Sundberg, M.; Warenholt, J.; György, C.; Sernbo, S.; Gustavsson, E.; Abu-Alsoud, W.; Wadström, T.; Borrebaeck, C. Strong lymphoid nuclear expression of SOX11 transcription factor defines lymphoblastic neoplasms, mantle cell lymphoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma. Haematologica 2009, 94, 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.Y.; Leshchenko, V.V.; Fazzari, M.J.; Perumal, D.; Gellen, T.; He, T.; Iqbal, J.; Baumgartner-Wennerholm, S.; Nygren, L.; Zhang, F.; et al. High-resolution chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) sequencing reveals novel binding targets and prognostic role for SOX11 in mantle cell lymphoma. Oncogene 2015, 34, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A.; Clot, G.; Prieto, M.; Royo, C.; Vegliante, M.C.; Amador, V.; Hartmann, E.; Salaverria, I.; Beà, S.; Martín-Subero, J.I.; et al. microRNA expression profiles identify subtypes of mantle cell lymphoma with different clinicobiological characteristics. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 3121–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, A.; Clot, G.; Royo, C.; Jares, P.; Hadzidimitriou, A.; Agathangelidis, A.; Bikos, V.; Darzentas, N.; Papadaki, T.; Salaverria, I.; et al. Molecular subsets of mantle cell lymphoma defined by the IGHV mutational status and SOX11 expression have distinct biologic and clinical features. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5307–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomero, J.; Vegliante, M.C.; Eguileor, A.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Balsas, P.; Martínez, D.; Campo, E.; Amador, V. SOX11 defines two different subtypes of mantle cell lymphoma through transcriptional regulation of BCL6. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1596–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomero, J.; Vegliante, M.C.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Eguileor, A.; Castellano, G.; Planas-Rigol, E.; Jares, P.; Ribera-Cortada, I.; Cid, M.C.; Campo, E.; et al. SOX11 promotes tumor angiogenesis through transcriptional regulation of PDGFA in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2014, 124, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegliante, M.C.; Palomero, J.; Pérez-Galán, P.; Roué, G.; Castellano, G.; Navarro, A.; Clot, G.; Moros, A.; Suárez-Cisneros, H.; Beà, S.; et al. SOX11 regulates PAX5 expression and blocks terminal B-cell differentiation in aggressive mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2013, 121, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegliante, M.C.; Royo, C.; Palomero, J.; Salaverria, I.; Balint, B.; Martín-Guerrero, I.; Agirre, X.; Lujambio, A.; Richter, J.; Xargay-Torrent, S.; et al. Epigenetic activation of SOX11 in lymphoid neoplasms by histone modifications. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Asplund, A.C.; Porwit, A.; Flygare, J.; Smith, C.I.; Christensson, B.; Sander, B. The subcellular Sox11 distribution pattern identifies subsets of mantle cell lymphoma: Correlation to overall survival. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 143, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Björklund, S.; Wasik, A.M.; Grandien, A.; Andersson, P.; Kimby, E.; Dahlman-Wright, K.; Zhao, C.; Christensson, B.; Sander, B. Gene expression profiling and chromatin immunoprecipitation identify DBN1, SETMAR and HIG2 as direct targets of SOX11 in mantle cell lymphoma. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvelebil, M.; Oliemuller, E.; Gao, Q.; Wansbury, O.; Mackay, A.; Kendrick, H.; Smalley, M.J.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Howard, B.A. Embryonic mammary signature subsets are activated in Brca1-/- and basal-like breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2013, 15, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, M.P.; Cornuet, P.K.; McIlwrath, S.; Koerber, H.R.; Albers, K.M. SRY-box containing gene 11 (Sox11) transcription factor is required for neuron survival and neurite growth. Neuroscience 2006, 143, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadi, J.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, M.J.; Jami, A.; Ruthala, K.; Kim, K.M.; Cho, N.H.; Jung, H.S.; Kim, C.H.; Lim, S.K. The transcription factor protein Sox11 enhances early osteoblast differentiation by facilitating proliferation and the survival of mesenchymal and osteoblast progenitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25400–25413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, M.F.; Ballestar, E.; Esteller, M. Capillary electrophoresis-based method to quantitate DNA–protein interactions. J. Chromatogr. B 2003, 789, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, M.S.; Nowling, T.K.; Rizzino, A. Identification of novel domains within Sox-2 and Sox-11 involved in autoinhibition of DNA binding and partnership specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 17901–17911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, X.; Wang, T.; Huang, S.; Glorioso, J.C.; Albers, K.M. The transcription factor Sox11 promotes nerve regeneration through activation of the regeneration-associated gene Sprr1a. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 233, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, O.K.; Schaefer, T.S.; Nathans, D. In vitro activation of Stat3 by epidermal growth factor receptor kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 13704–13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, J.E., Jr. STATs and gene regulation. Science 1997, 277, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liao, D.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Chuang, T.-H.; Xiang, R.; Markowitz, D.; Reisfeld, R.A.; Luo, Y. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Regulate Murine Breast Cancer Stem Cells Through a Novel Paracrine EGFR/Stat3/Sox-2 Signaling Pathway. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yin, L.; Pu, T.; Wei, J.; Karthikeyan, V.; Lin, T.-P.; Gao, A.C.; Wu, B.J. Neuropilin-2 promotes lineage plasticity and progression to neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Oncogene 2022, 41, 4307–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, O.A.; Chasovskikh, S.; Lonskaya, I.; Tarasova, N.I.; Khavrutskii, L.; Tarasov, S.G.; Zhang, X.; Korostyshevskiy, V.R.; Cheema, A.; Zhang, L.; et al. Mechanisms of unphosphorylated STAT3 transcription factor binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 14192–14200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Y.; Makino, K.; Xia, W.; Matin, A.; Wen, Y.; Kwong, K.Y.; Bourguignon, L.; Hung, M.C. Nuclear localization of EGF receptor and its potential new role as a transcription factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001, 3, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, U.; Ruchti, C.; Kampf, J.; Thomas, G.A.; Williams, E.D.; Peter, H.J.; Gerber, H.; Burgi, U. Nuclear localization of epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptors in human thyroid tissues. Thyroid 2001, 11, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, H.W.; Xia, W.; Wei, Y.; Ali-Seyed, M.; Huang, S.F.; Hung, M.C. Novel prognostic value of nuclear epidermal growth factor receptor in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psyrri, A.; Yu, Z.; Weinberger, P.M.; Sasaki, C.; Haffty, B.; Camp, R.; Rimm, D.; Burtness, B.A. Quantitative determination of nuclear and cytoplasmic epidermal growth factor receptor expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer by using automated quantitative analysis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 5856–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, A.; Gamelin, E.; Coqueret, O. The EGFR-STAT3 oncogenic pathway up-regulates the Eme1 endonuclease to reduce DNA damage after topoisomerase I inhibition. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Tian, Y.; Buettner, R.; Hsieh, M.Y.; Horne, D.; Dellinger, T.H.; Han, E.S.; Jove, R.; et al. Synergistic anti-tumor effect of combined inhibition of EGFR and JAK/STAT3 pathways in human ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Rabii, R.; Liang, G.; Song, C.; Chen, W.; Guo, M.; Wei, X.; Messadi, D.; Hu, S. The Expression Levels of XLF and Mutant P53 Are Inversely Correlated in Head and Neck Cancer Cells. J. Cancer 2016, 7, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misuno, K.; Liu, X.; Feng, S.; Hu, S. Quantitative proteomic analysis of sphere-forming stem-like oral cancer cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.; Sandoval, N.; Phan, A.; Nguyen, T.V.; Chen, R.W.; Budde, E.; Mei, M.; Popplewell, L.; Pham, L.V.; Kwak, L.W.; et al. Regulation of SOX11 expression through CCND1 and STAT3 in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2019, 133, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.T.; Zhong, H.T.; Li, G.W.; Shen, J.X.; Ye, Q.Q.; Zhang, M.L.; Liu, J. Oncogenic functions of the EMT-related transcription factor ZEB1 in breast cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. EMT: When epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1417–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Craene, B.; Berx, G. Regulatory networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frixen, U.H.; Behrens, J.; Sachs, M.; Eberle, G.; Voss, B.; Warda, A.; Lochner, D.; Birchmeier, W. E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion prevents invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 1991, 113, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.H.; Wu, M.Z.; Chiou, S.H.; Chen, P.M.; Chang, S.Y.; Liu, C.J.; Teng, S.C.; Wu, K.J. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1α promotes metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.; Lapouge, G.; Rorive, S.; Drogat, B.; Desaedelaere, K.; Delafaille, S.; Dubois, C.; Salmon, I.; Willekens, K.; Marine, J.C.; et al. Different levels of Twist1 regulate skin tumor initiation, stemness, and progression. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.M.; Oliemuller, E.; Howard, B.A. Regulatory roles for SOX11 in development, stem cells and cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 67, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sock, E.; Rettig, S.D.; Enderich, J.; Bösl, M.R.; Tamm, E.R.; Wegner, M. Gene targeting reveals a widespread role for the high-mobility-group transcription factor Sox11 in tissue remodeling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 6635–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Peng, J.; Cui, L.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Jia, W.; Misuno, K.; Barrett, J.; Messadi, D.; Yang, S.-F.; Hu, S. SOX11 Is Regulated by EGFR-STAT3 and Promotes Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells 2026, 15, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010084

Peng J, Cui L, Guo M, Liu Y, Jia W, Misuno K, Barrett J, Messadi D, Yang S-F, Hu S. SOX11 Is Regulated by EGFR-STAT3 and Promotes Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells. 2026; 15(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010084

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Jiayi, Li Cui, Mian Guo, Yi Liu, Wanqi Jia, Kaori Misuno, Jeremy Barrett, Diana Messadi, Shun-Fa Yang, and Shen Hu. 2026. "SOX11 Is Regulated by EGFR-STAT3 and Promotes Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Cells 15, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010084

APA StylePeng, J., Cui, L., Guo, M., Liu, Y., Jia, W., Misuno, K., Barrett, J., Messadi, D., Yang, S.-F., & Hu, S. (2026). SOX11 Is Regulated by EGFR-STAT3 and Promotes Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cells, 15(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010084