The Oral Microbiota: Implications in Mucosal Health and Systemic Disease—Crosstalk with Gut and Brain

Highlights

- Current evidence suggests that oral dysbiosis may influence distant tissues through immune activation, microbial translocation and low-grade systemic inflammation, and is not limited to periodontal pathology.

- Key oral bacteria, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Filifactor alocis, interact with mucosal surfaces and contribute to inflammatory and metabolic pathways that link the oral cavity to the gut and brain.

- Maintaining the balance of oral microbiota may help to preserve the integrity of the epithelial barrier and modulate mucosa-associated immune responses, which could have protective effects against systemic inflammatory and degenerative diseases.

- Understanding the mechanisms underlying oral-gut–brain crosstalk could lead to new opportunities for the early prevention and risk stratification of systemic diseases, as well as the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Oral Microbiota Homeostasis

3. Imbalance of Oral Microbiota and Disease

4. Porphyromonas gingivalis

5. Fusobacterium nucleatum

6. Effects of Other Periodontal Pathogens

7. Taste Receptors and Microbiota

8. Gut Microbiota and Gut–Brain Axis

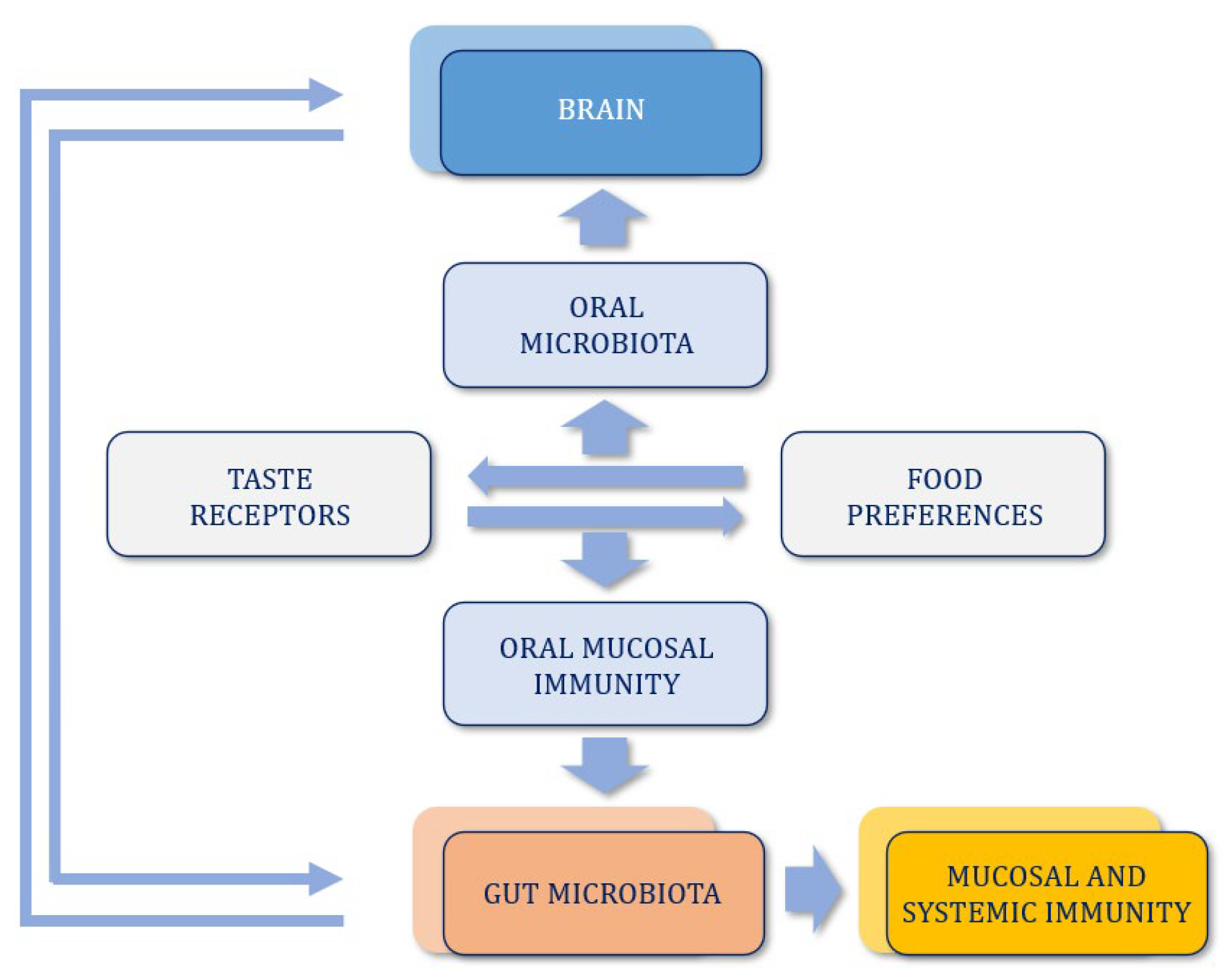

9. Oral–Gut–Brain Axis

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid β |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CEACAM | Carcinoembryonic Antigen-related Cell Adhesion molecules |

| Cdt | Cytolethal Distending Toxin |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DAMPs | Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| ESCC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| FadA | Fusobacterium adhesin A |

| FapA | Fusobacterium outer membrane protein A |

| Fap2 | Fusobacterium outer membrane autotransporter protein 2 |

| FH | Factor H |

| GBA | Gut–Brain Axis |

| HNSCC | Head-Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HPA | Hypoyhalamus Pituitary Adrenal |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IEB | Intestinal Epithelial Barrier |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LGCI | Low Grade Chronic Inflammation |

| LPS | Lipopolisaccharide |

| LSCC | Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| LtxA | Leukotoxin A |

| MALT | Mucosa Associated Lymphoid Tissue |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MPPs | Metalloproteinases |

| MSP | Major Sheath Protein |

| MurNAc | N-Acetyl Muramic Acid |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain Enhancer of Activate B Cells |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain- containing protein 3 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| OMVs | Outer Membrane Vescicles |

| OPSCC | Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| OSCC | Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| PAD | Peptidyl-Arginine Deaminase |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate |

| PKB/AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| PNEI | Psycho-Neuro-Endocrine-Immunology |

| RadD | Radiation-sensitive DNA Adhesin |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RTX | Repeats in-Toxin |

| SCFA | Short Chain Fatty Acid |

| SPF | Specific Pathogen Free |

| Th | T helper Lymphocyte |

| TIGIT | T Cells Immunoreceptors with Ig and ITIM domains |

| TLR2 | Toll Like Receptor 2 |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TR | Taste Receptor |

| Treg | T regulatory Lymphocyte |

References

- Miller, W.D. The Human Mouth as a Focus of Infection. Lancet 1891, 138, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagier, J.C.; Hugon, P.; Khelaifia, S.; Fournier, P.E.; Raoult, D. Human Gut Microbiota: Repertoire and Variations. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignatelli, P.; Mura, F.; Falcone, E.; Laghi, L. Microbiota and Oral Cancer as a Complex and Dynamic Microenvironment: A Narrative Review from Etiology to Prognosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffajee, A.D.; Socransky, S.S. Microbial Complexes in Supragingival Plaque. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 23, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Haake, S.K.; Mannon, P.; Lemon, K.P.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Huttenhower, C.; Izard, J. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaura, E.; Keijser, B.J.F.; Huse, S.M.; Crielaard, W. Defining the healthy “core microbiome” of oral microbial communities. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Ghosh, T.S.; Bhute, S.S.; Vaidya, S.; Koylass, M.; Gokul, J.K.; Ballal, S.A.; Tripathi, A.; Ghosh, S.; Sharma, V.K.; et al. The human oral microbiome and its role in health and disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1197, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, J.L.M.; Rossetti, B.J.; Rieken, C.W.; Dewhirst, F.E.; Borisy, G.G. Oral Microbiome Geography: Micron-Scale Habitat and Niche. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzenbach, T.; Brandt, C.; Batzilla, J. Bioadhesion in the Oral Cavity and Approaches for Biofilm Management by Surface Modifications. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 4237–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L.; O’Donnell, L.; Lamont, R.J. The Oral Microbiome: Diversity, Biogeography and Human Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Oral Microbiota in Human Systemic Diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, P.D.; Zaura, E. Dental biofilm: Ecological interactions in health and disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, S12–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, A.M.L.; Sørensen, C.E.; Proctor, G.B.; Carpenter, G.H.; Ekström, J. Salivary secretion in health and disease. J. Oral Rehabil. 2019, 46, 730–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, M. Salivary proteins and peptides in oral host defence. Adv. Dent. Res. 2020, 32, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, T.; Sultan, A.S.; Montelongo-Jauregui, D.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A. Oral candidiasis: A disease of opportunity. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.; Devine, D.A.; Marsh, P.D. Oral biofilms: Molecular analysis, challenges, and future directions. J. Oral Microbiol. 2024, 16, 2323456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, T. Oral epithelial barrier integrity and host–microbiota interactions. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 118245. [Google Scholar]

- Nibali, L.; Donos, N.; Henderson, B. Periodontal disease susceptibility and genetic polymorphisms. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.S. Genetics of periodontitis: Discovery, biology, and clinical impact. Periodontology 2000, 78, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Sharma, S.; Chandra, H. Biofilm Modifiers: The Disparity in Paradigm of Oral Biofilm Ecosystem. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H. Macrophages: A Communication Network Linking Porphyromonas Gingivalis Infection and Associated Systemic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 952040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Cabanyero, C.; Vonaesch, P. Ectopic Colonization by Oral Bacteria as an Emerging Theme in Health and Disease. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 48, fuae012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannapieco, F.A.; Cantos, A. Oral inflammation and respiratory diseases. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Scannapieco, F.A. The oral–lung axis. Periodontology 2000, 92, 210–222. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, J.L.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Ge, L. The role of oral microbiota in respiratory health and diseases. Respir. Res. 2021, 185, 106475. [Google Scholar]

- Carrizales-Sepúlveda, E.F. Periodontal inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2018, 14, 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, M.; del Castillo, A.M.; Jepsen, S.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; D’aiuto, F.; Bouchard, P.; Chapple, I.; Dietrich, T.; Gotsman, I.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 47, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum: A multifaceted pathogen. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Buhimschi, C.S.; Temoin, S.; Bhandari, V. Comparative microbial analysis of amniotic fluid and cord blood. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56146. [Google Scholar]

- Vojdani, A.; Kharrazian, D.; Mukherjee, P. The Role of Exposomes in the Pathophysiology of Autoimmune Diseases II: Pathogens. Pathophysiology 2022, 29, 243–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, M.; Liu, H.; Ziebolz, D.; Schmalz, G. More than just a periodontal pathogen—The research progress on Fusobacterium nucleatum. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 815318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Inflammasome activation and bone loss. J. Periodontol. 2020, 91, 132–144. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, C.M.; Boeree, E.; Tellez Freitas, C.M.; Weber, K.S. Immunomodulatory role of oral microbiota in inflammatory diseases and allergic conditions. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1067483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Roy, S.; Banerjee, R. Role of Oral Microbiome Signatures in Diagnosis and Prognosis of Oral Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 18, 1533033819867354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, P. Dysbiosis Linking Periodontal Disease and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Brief Narrative Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, O.A.; Novak, M.J.; Kirakodu, S.; Stromberg, A.J.; Nagarajan, R.; Huang, C.B.; Chen, K.C.; Orraca, L.; Martinez-Gonzalez, J.; Ebersole, J.L. Differential gene expression profiles reflecting macrophage polarization in aging and periodontitis gingival tissues. Immunol. Investig. 2015, 44, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, D.; Han, X.; Feng, X.; Zhu, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Macrophage polarization in periodontal disease. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Champaiboon, C.; Champaiboon, C.; Christensen, S.S.S.J.; Reppe, J.; Vik, O.K.V.J. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Li, J. NLRP3 inflammasome in periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 818241. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Kurita-Ochiai, T.; Kobayashi, R.; Suzuki, T.; Ando, T.; Yamamoto, M. Porphyromonas gingivalis and IL-1β induction. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00055-17. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, P.; Liu, X.; Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Canonical and non-canonical inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Okano, T.; Oshima, M.; Yamada, S.; Yanagita, M. Periodontal inflammation and cytokine expression. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 60, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Taxman, D.J.; Champaiboon, C.; Christensen, S.S.S.J.; Reppe, J.; Vik, O.K.V.J. Caspase-1 inhibition by P. gingivalis. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002524. [Google Scholar]

- Kelk, P.; Johansson, A.; Claesson, R.; Hänström, L.; Kalfas, S. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin and inflammasome activation. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 4589–4600. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L.; Khan, S. Oral Microbes Are a Signature of Disease in the Gut. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Q. Characterization of the Oral and Esophageal Microbiota in Esophageal Precancerous Lesions and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 714162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuna, H.; Martínez-Castañón, G.A.; Niño-Martínez, N.; Patiño-Marín, N.; Loyola-Rodríguez, J.P. Periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 828195. [Google Scholar]

- Bowland, G.B.; Weyrich, L.S. The Oral-Microbiome-Brain Axis and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: An Anthropological Perspective. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 810008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Periodontitis-Related Salivary Microbiota Aggravates Alzheimer’s Disease via Gut-Brain Axis Crosstalk. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, e2126272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M. Porphyromonas Gingivalis in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains: Evidence for Disease Causation and Treatment with Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. Mitochondria: An Emerging Unavoidable Link in the Pathogenesis of Periodontitis Caused by Porphyromonas Gingivalis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, S.W.; Tsang, C.M.; To, K.F. Epstein–Barr Virus Infection and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economopoulou, P.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A. A Special Issue about Head and Neck Cancers: HPV Positive Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X. Oral Microbiota: The Overlooked Catalyst in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 12, 1479720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X. Role of Oral Microbiome in Oral Oncogenesis, Tumor Progression, and Metastasis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 38, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Chen, C.; Hayes, R.B. Periodontal Disease, Porphyromonas Gingivalis Serum Antibody Levels and Orodigestive Cancer Mortality. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neculae, E.; Popescu, C.; Petrescu, S. The Oral Microbiota in Valvular Heart Disease: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Life 2023, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolstad, A.I.; Jensen, H.B.; Bakken, V. Taxonomy, Biology, and Periodontal Aspects of Fusobacterium Nucleatum. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 9, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiscuzzu, F.; Bianconi, E.; Laghi, L. Current Evidence on the Relation between Microbiota and Oral Cancer—The Role of Fusobacterium Nucleatum—A Narrative Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium Nucleatum: A Commensal-Turned Pathogen. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 23, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Fusobacterium Nucleatum in Tumors: From Tumorigenesis to Tumor Metastasis and Tumor Resistance. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2306676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kook, J.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, D. Genome-Based Reclassification of Fusobacterium Nucleatum Subspecies at the Species Level. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 74, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.; Han, Y.W.; Kaplan, S. Oral Infection of Mice with Fusobacterium Nucleatum Results in Macrophage Recruitment to the Dental Pulp and Bone Resorption. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, B.F.; Xing, L. TNF-Alpha and Pathologic Bone Resorption. Keio J. Med. 2005, 54, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupan, J.; Grcevic, D.; Kovacic, N. Osteoimmunology and the Influence of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines on Osteoclasts. Biochem. Med. 2013, 23, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Facilitates Apoptosis, ROS Generation, and Inflammatory Cytokine Production by Activating AKT/MAPK and NF-κB Signaling Pathways in Human Gingival Fibroblasts. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 1681972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Yamada, M.; Amano, A. Porphyromonas Gingivalis Entry into Gingival Epithelial Cells Modulated by Fusobacterium Nucleatum Is Dependent on Lipid Rafts. Microb. Pathog. 2012, 53, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Isaacson, B. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Suppresses Anti-Tumor Immunity by Activating CEACAM1. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1581531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, K.; Baba, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Mima, K.; Kurashige, J.; Ueno, S.; Nishioka, Y.; Ishimoto, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Intratumoral Fusobacterium Nucleatum Levels Predict Therapeutic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6150–6161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Infection Is Prevalent in Human Colorectal Carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Xiao, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhou, H.; Tang, W.; et al. Dysbiosis Signature of Fecal Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 66, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelk, P. Leukotoxin A–induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 111, 987–998. [Google Scholar]

- Sordi, M.B. Pyroptosis in periodontal inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658234. [Google Scholar]

- Rompikuntal, P.K.; Thay, B.; Hays, E.; Güssmann, C.; Lamont, R.J.; Demuth, D.R.; Jenkinson, H.F. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans outer membrane vesicles mediate immune activation. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, S.; Kowashi, Y.; Demuth, D.R. Outer membrane vesicles of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontal Res. 2002, 37, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth, D.R.; James, D.; Kowashi, Y. Characterization of leukotoxin-containing vesicles. Microb. Pathog. 2003, 34, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Karched, M.; Ihalin, R.; Eneslätt, K.; Eneslätt, K.; Asikainen, S. Peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 3437–3446. [Google Scholar]

- Goulhen, F.; Hafezi, A.; Uitto, V.J. GroEL chaperonin as a virulence factor in periodontal bacteria. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 4135–4142. [Google Scholar]

- Thay, B.; Damm, A.; Kufer, T.A.; Wiese, A.; Höltje, J.-V.; Bertsche, U. NOD1- and NOD2-active peptidoglycan in periodontal pathogens. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 3130–3140. [Google Scholar]

- Razooqi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Aruni, A.W.; Roy, F.; Muthiah, A.; Fletcher, H.M. RTX ftxA toxin and Filifactor alocis pathogenicity. J. Periodontal Res. 2024, 59, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Razooqi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Aruni, A.W.; Roy, F.; Muthiah, A.; Fletcher, H.M. Filifactor alocis and clinical attachment loss progression. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1178456. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Roy, F.; Aruni, A.W.; Muthiah, A.; Gonzalez, D.J.; Fletcher, H.M. Oxidative stress resistance mechanisms of Filifactor alocis. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00345-20. [Google Scholar]

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Cugini, M.A.; Smith, C.; Kent, R.L. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998, 25, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.C.; Ebersole, J.L. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola. Periodontology 2000 2005, 38, 72–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.P. Sialidase activity in periodontal pathogens. Microbiology 2022, 168, 001123. [Google Scholar]

- Honma, K.; Mishima, E.; Shibata, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Uematsu, H.; Shibata, T. NanH sialidase of Tannerella forsythia. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottmann, I.; Voglauer, R.; Honma, K.; Sharma, A.; Schäffer, C. MurNAc auxotrophy and biofilm survival of Tannerella forsythia. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2021, 36, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlet, S.; Pike, R.N.; McGraw, W.T.; Hunter, N.; Bartold, P.M.; Rogers, A.H. PrtH cysteine protease of Tannerella forsythia. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 2565–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek, M.; Mizgalska, D.; Eick, S.; Thøgersen, I.B.; Enghild, J.J. KLIKK proteases in periodontal pathogens. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2015, 30, 294–306. [Google Scholar]

- Jusko, M.; Potempa, J.; Mizgalska, D.; Bielinska, E.; Ksiazek, M.; Enghild, J.J. Karilysin inhibits complement activation. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 314–322. [Google Scholar]

- Koneru, L.; Potempa, J.; Kantyka, T.; Mizgalska, D.; Bielecka, E.; Bachrach, G. Cathelicidin inactivation by periodontal proteases. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00561-16. [Google Scholar]

- Koziel, J.; Potempa, J.; Bereswill, S.; Hänsch, G.M. Immune evasion strategies of Tannerella forsythia. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Posch, G.; Sekot, G.; Friedrich, V.; Zayni, S.; Messner, P.; Schäffer, C. S-layer proteins of Tannerella forsythia. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2011, 26, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sekot, G.; Posch, G.; Messner, P.; Matejka, M.; Rausch-Fan, X.; Schäffer, C. TfsA and TfsB proteins in host interaction. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 921–926. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, F. Tannerella forsythia immune modulation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1189234. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, S.; Sekot, G.; Posch, G.; Schäffer, C.; Messner, P.; Friedrich, V. S-layer mediated immune evasion. Cell. Microbiol. 2018, 20, e12887. [Google Scholar]

- Settem, R.P.; Honma, K.; Nakajima, T.; Pham, T.T.; Sharma, A.; McBride, B.C. Tannerella forsythia–host interaction. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 2728–2737. [Google Scholar]

- Onishi, S.; Honma, K.; Shibata, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Uematsu, H.; Shibata, T. TLR2-mediated BspA signalling. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 5819–5827. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Sojar, H.T.; Glurich, I.; De Nardin, E. BspA-induced cytokine release. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 20300–20305. [Google Scholar]

- Haheim, L.L.; Rønningen, K.S.; Olsen, I.; Ravndal, E.; Bjørnholt, J.V.; Haug, E.S.; Hansen, B.F.; Holm, S.; Skarstein, K.; Schirmer, H.; et al. Atherosclerosis and periodontal pathogens. Atherosclerosis 2020, 297, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, V.; Bloch, S.; Sekot, G.; Posch, G.; Schäffer, C.; Messner, P. OMVs of Tannerella forsythia induce inflammation. Cell. Microbiol. 2020, 22, e13155. [Google Scholar]

- Cimasoni, G. The role of Treponema denticola in periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 1987, 22, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, A.; Holt, S.C. Chemical and biological activities of Treponema denticola outer membrane vesicles. Infect. Immun. 1991, 59, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, M.J.; Kesty, N.C. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host–pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2645–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, B.; Qi, M.; Kuramitsu, H.K. Role of dentilysin in Treponema denticola epithelial cell layer penetration. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.H. Toxin–antitoxin systems in oral spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 7071–7079. [Google Scholar]

- Makarova, K.S.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V. Comprehensive comparative-genomic analysis of toxin–antitoxin systems and their evolution. Biol. Direct 2009, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Romano, G.H.; Groisman, B.; Yona, A.; Dekel, E.; Kupiec, M.; Dahan, O.; Pilpel, Y. Adaptive prediction of environmental changes by microorganisms. Nature 2010, 460, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayraman, A.; Wood, T.K. Bacterial quorum sensing: Signals, circuits, and implications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 10, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uitto, V.J.; Grenier, D.; McBride, B.C. Isolation and characterization of a chymotrypsin-like protease from Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 1988, 56, 2717–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makinen, K.K.; Makinen, P.L. Purification and properties of dentilysin from Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 3472–3477. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, K.; Kuramitsu, H.K.; Okuda, K. Molecular cloning and expression of a Treponema denticola protease gene. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 5178–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausejour, D.; Grenier, D.; Mayrand, D. Proteolytic activity of Treponema denticola on extracellular matrix components. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 476–481. [Google Scholar]

- Grenier, D.; Mayrand, D. Functional characterization of Treponema denticola proteases. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, D.R.; Wang, C.; Danaher, R.J. Dentilysin-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. J. Periodontal Res. 1990, 25, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, J.V.; Huang, B.; Fenno, J.C.; Marconi, R.T. Analysis of a Treponema denticola factor H binding protein. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Pangburn, M.K.; Muller-Eberhard, H.J. The alternative pathway of complement. J. Exp. Med. 1977, 146, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddy, S.; Austen, K.F. Activation of the alternative complement pathway. J. Immunol. 1969, 102, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniyati, K.; Zhang, Y.; Kelly, A.; Yang, Z.; McBride, J.W.; Fenno, J.C. A Treponema denticola neuraminidase promotes complement resistance. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3623–3633. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, M.B.; Ellen, R.P. Treponema denticola major surface protein disrupts actin dynamics. Cell. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, R.P.; Galimanas, V.B. Spirochetes at the forefront of periodontal infections. Periodontology 2000 2005, 38, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, M.N. Role of Treponema denticola in periodontal diseases. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2001, 12, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Ho, A.C.; Lin, J.Y. Cytoskeletal disruption induced by periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 2004, 83, 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Puthengady Thomas, B.; Prabhu, S.R. Chemotaxis alterations in periodontal disease. J. Periodontal Res. 2006, 41, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Ko, K.S.; Kapus, A.; McCulloch, C.A. A spirochetal surface protein alters actin dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell 2002, 13, 402–415. [Google Scholar]

- Uitto, V.J.; McBride, B.C. Role of Treponema denticola in actin cytoskeleton modulation. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Morfini, G.; Pigino, G.; Beffert, U.; Busciglio, J.; Brady, S.T. Fast axonal transport dysfunction in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 559–573. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1762, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, H.; Moraes, C.T. Mitochondrial impairment in neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, M.P.; Gleichmann, M.; Cheng, A. Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron 2008, 60, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; Yu, L.; Xie, H.; Dong, C.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W. Oral Microbiota-Host Interaction Mediated by Taste Receptors. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 802504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Jones, G.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z. Dynamic Evolution of Bitter Taste Receptor Genes in Vertebrates. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, A.D.; Palmer, J.N.; Adappa, N.D.; Cohen, N.A. The Role of Bitter and Sweet Taste Receptors in Upper Airway Immunity. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015, 15, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Staszewski, L.; Xu, H.; Durick, K.; Zoller, M.; Adler, E. Human Receptors for Sweet and Umami Taste. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4692–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, I.; Nakagawa, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Yamada, H. The Role of the Sweet Taste Receptor in Enteroendocrine Cells and Pancreatic β-Cells. Diabetes Metab. J. 2011, 35, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, G.A.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Sweet Taste Receptor Signaling in Beta Cells Mediates Fructose-Induced Potentiation of Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E524–E532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. The Receptors for Mammalian Sweet and Umami Taste. Cell 2003, 115, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basson, M.D.; Smith, R.; Johnson, K.; Lee, C. Association between 6-N-Propylthiouracil (PROP) Bitterness and Colonic Neoplasms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2005, 50, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennella, J.A.; Pepino, M.Y.; Reed, D.R. Genetic and environmental determinants of bitter perception and sweet preferences. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e1250–e1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepper, B.J.; White, E.A.; Koelliker, Y.; Lanzara, C.; d’Adamo, P.; Gasparini, P. Genetic variation in bitter taste receptor TAS2R38 and the perception of bitter taste. Chem. Senses 2008, 33, 611–619. [Google Scholar]

- Jaggupilli, A.; Singh, N.; Upadhyaya, J.; Sikarwar, A.S.; Arakawa, M.; Dakshinamurti, S.; Chelikani, P. Analysis of the expression of human bitter taste receptors in extraoral tissues. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 454, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Cohen, N.A. Taste receptors in innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, R.M.; Lee, R.J. Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2017, 24, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.J.; Xiong, G.; Kofonow, J.M.; Chen, B.; Lysenko, A.; Jiang, P.; Abraham, V.; Doghramji, L.; Adappa, N.D.; Palmer, J.N.; et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 122, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, A.; Das, R. An Insight into Gut Microbiota and Its Functionalities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belizário, J.E.; Faintuch, J.; Garay-Malpartida, M.; de Carvalho, F.A.; Rocha, V.; Justino, T.; Dias-Neto, E.; Mota, J.F. Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Immunometabolism: New Frontiers for Treatment of Metabolic Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 2037838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantrappen, G.; Janssens, J.; Peeters, M.; Hiele, M.; De Roo, M. The Interdigestive Motor Complex of Normal Subjects and Patients with Bacterial Overgrowth of the Small Intestine. J. Clin. Investig. 1977, 59, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, P.G.; Hooper, L.V.; Midtvedt, T.; Gordon, J.I. Creating and Maintaining the Gastrointestinal Ecosystem: What We Know and Need to Know from Gnotobiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1998, 62, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannock, G.W.; Savage, D.C. Influences of Dietary and Environmental Stress on Microbial Populations in the Murine Gastrointestinal Tract. Infect. Immun. 1974, 9, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gareau, M.G.; Sherman, P.M.; Walker, W.A. Probiotic Treatment of Rat Pups Normalises Corticosterone Release and Ameliorates Colonic Dysfunction Induced by Maternal Separation. Gut 2007, 56, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.T.; Coe, C.L. Maternal Separation Disrupts the Integrity of the Intestinal Microflora in Infant Rhesus Monkeys. Dev. Psychobiol. 1999, 35, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, S.M.; Clarke, G.; Borre, Y.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Early Life Stress Alters Behavior, Immunity, and Microbiota in Rats: Implications for Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Psychiatric Illnesses. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbonnet, L.; Garrett, L.; Clarke, G.; Bienenstock, J.; Dinan, T.G. The Probiotic Bifidobacterium Infantis: An Assessment of Potential Antidepressant Properties in the Rat. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 43, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehler, L.E.; Park, S.; Opitz, N.; Lyte, M.; Gaykema, R.P. Infection-Induced Viscerosensory Signals from the Gut Enhance Anxiety: Implications for Psychoneuroimmunology. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Y. Evidences for Vagus Nerve in Maintenance of Immune Balance and Transmission of Immune Information from Gut to Brain in STM-Infected Rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 8, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercik, P.; Verdu, E.F.; Foster, J.A.; Macri, J.; Potter, M.; Huang, X.; Malinowski, P.; Jackson, W.; Blennerhassett, P.A.; Collins, S.M. Immune-Mediated Neural Dysfunction in a Murine Model of Chronic Helicobacter Pylori Infection. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.E.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, H.J.; Han, M.J.; Kim, D.H. Gastrointestinal Inflammation by Gut Microbiota Disturbance Induces Memory Impairment in Mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N.; Chida, Y.; Aiba, Y.; Sonoda, J.; Oyama, N.; Yu, X.N.; Kubo, C.; Koga, Y. Postnatal Microbial Colonization Programs the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal System for Stress Response in Mice. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; Antonioli, L.; Colucci, R.; Di Paola, R.; Fornai, M.; Blandizzi, C. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease: Is NLRP3 Inflammasome at the Crossroads of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Communications? Prog. Neurobiol. 2020, 191, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Adeyemo, M.; Karunanayake, C.; Swain, J.R.; Qian, W.; Bercik, P. Brain–Gut–Microbiota Axis in Depression: A Historical Overview and Future Directions. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 182, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamoto, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Jiao, Y.; Gillilland, M.G.; Hayashi, A.; Imai, J.; Sugihara, K.; Miyoshi, M.; Brazil, J.C.; Kuffa, P.; et al. Oral–gut axis and inflammatory disease. Cell 2020, 182, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, K.; Tanoue, T.; Ando, M.; Kamada, N.; Nagamori, T.; Narushima, S.; Suda, W.; Imanishi, Y.; Hase, K.; Ohno, H.; et al. Th17 cell induction by microbiota. Cell 2017, 163, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, H.; et al. Oral microbiota–driven neuroinflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 906738. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgart, H.R.; Gosalbez, A.; Lee, C.; Foster, J.A.; Walker, W.A.; McVey, D.M. Microbial Involvement in Alzheimer Disease Development and Progression. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goellner, E.; Rocha, C.E. Anatomy of Trigeminal Neuromodulation Targets: From Periphery to the Brain. Prog. Neurol. Surg. 2020, 35, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Karr, J.E.; Areshenkoff, C.N.; Garcia-Barrera, M.A.; Logan, A.R.; Burke, S.L.; Hogervorst, E.; Allard, E.S. When Does Cognitive Decline Begin? A Systematic Review of Change Point Studies on Accelerated Decline in Cognitive and Neurological Outcomes Preceding Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia, and Death. Psychol. Aging 2018, 33, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, L. Porphyromonas Gingivalis Infection Induces Amyloid-β Accumulation in Monocytes/Macrophages. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 72, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; König, J.; Schmalz, G.; Scully, C.; Huber, S.; Flemmig, T.F. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Oral Health: Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C.N.; Fried, M.; Krugliak, P.; Cohen, A.; Eliakim, R.; Fedail, S.; Bitton, A.; Shanahan, F.; Ghosh, S.; Vael, C.; et al. Increased Burden of Psychiatric Disorders in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Chen, T.; Izard, J.; Paster, B.J.; Tanner, A.C.R.; Yu, W.-H.; Lakshmanan, A.; Wade, W.G. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Microbial Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

| Tongue | Streptococcus | australis, parasanguinis, |

| salivarius | ||

| Veillonella | dispar, parvula | |

| Fusobacterium | periodonticum | |

| Prevotella | nancelensis | |

| Atropobium | parvulum | |

| Granulicatella | adiacens, hemolysans | |

| Tooth surface, subgingival plaque and gingival epithelium | Parviromonas | micros |

| Streptococcus | gordonii, intermedius, | |

| mitis, oralis, sanguinis | ||

| Actinomyces | israelii, naeslundii, | |

| odontolyticus | ||

| Capnocytophaga | gingivalis, sputigena, | |

| ochracea | ||

| Eikenella | corrodens | |

| Neisseria | mucosa | |

| Veillonella | parvula | |

| Campylobacter | gracilis, rectus, showae | |

| Selenomonas | noxia | |

| Prevotella | intermedia, nigrescens, | |

| melaninogenica | ||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | spp. nucleatum, | |

| spp. polymorphum | ||

| spp. vincentii | ||

| spp. periodonticum | ||

| Eubacterium | nodatum | |

| Porphyromonas | gingivalis, CW034 | |

| Tannerella | forsythia | |

| Treponema | denticola, socranskii | |

| Aggregatibacter | actinomycemcomitans | |

| Filifactor | alocis | |

| Corynebacterium | durum | |

| Granulicatella | hemolysans | |

| Gemella | morbillorum | |

| Bergeyella | 602d02 | |

| Buccal Mucosa | Streptococcus | mitis |

| Rothia | mucilaginosa | |

| Actinomyces | odontolitycus | |

| Neisseria | subflava | |

| Saliva | Aggregatibacter | actinomycemcomitans, segnis |

| Neisseria | subflava, bacilliformis | |

| Veillonella | dispar, parvula | |

| Prevotella | melaninogenica, pallens, | |

| nanceiensis, nigrescens | ||

| Rothia | dentocariosa, mucilaginosa | |

| Streptococcus | anginosus | |

| Porphyromonas | endodontalis | |

| Fusobacterium | sp. | |

| Capnocytophaga | ochracea | |

| Treponema | amylovorum | |

| Peptostreptococcus | anaerobius | |

| Tonsil and oropharyngeal region | Streptococcus | anginosus, mutans, |

| pneumoniae, pyogenes, | ||

| viridans | ||

| Prevotella | - | |

| Haemophylus | influenza, parainfluenzae | |

| Neisseria | - |

| Microbial | Activity |

|---|---|

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | upregulation of NLRP3 inflammasome |

| increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines | |

| anti-inflammatory cytokines inhibition | |

| increase in expression of MMPs | |

| triggering of autoimmune disease by PAD enzyme | |

| NASH induction | |

| increase of triglycerides in hepatic tissue | |

| hepatic cirrhosis induction | |

| insulin-resistance induction | |

| apoptosis inhibition (inhibition Caspase-3; increase Bcl-2) | |

| alteration of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation | |

| OSCC induction and progression | |

| production of β-indolic compounds in the gut | |

| neurotoxicity (tau protein damage and β-amyloid protein production) |

| Microbial | Activity |

|---|---|

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | intestinal inflammation induction |

| NF-κB activation | |

| increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines | |

| increase in immunosuppression | |

| increase in ROS | |

| inhibition of gengival fibroblast proliferation | |

| production of β-indolic compounds in the gut | |

| CRC, SCC, ESCC induction and progression of breast cancer induction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Miranda, V.; Laarej, K.; Cavaliere, C. The Oral Microbiota: Implications in Mucosal Health and Systemic Disease—Crosstalk with Gut and Brain. Cells 2026, 15, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010082

Miranda V, Laarej K, Cavaliere C. The Oral Microbiota: Implications in Mucosal Health and Systemic Disease—Crosstalk with Gut and Brain. Cells. 2026; 15(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiranda, Vincenzo, Kamilia Laarej, and Carlo Cavaliere. 2026. "The Oral Microbiota: Implications in Mucosal Health and Systemic Disease—Crosstalk with Gut and Brain" Cells 15, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010082

APA StyleMiranda, V., Laarej, K., & Cavaliere, C. (2026). The Oral Microbiota: Implications in Mucosal Health and Systemic Disease—Crosstalk with Gut and Brain. Cells, 15(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010082