Neuroimmune Regulation by TRPM2 Channels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. TRPM2 Activation

2.1. NAD-Derived Metabolites

2.2. Ca2+ Activation of TRPM2

2.3. Temperature Activation of TRPM2

3. TRPM2 in Thermoregulation

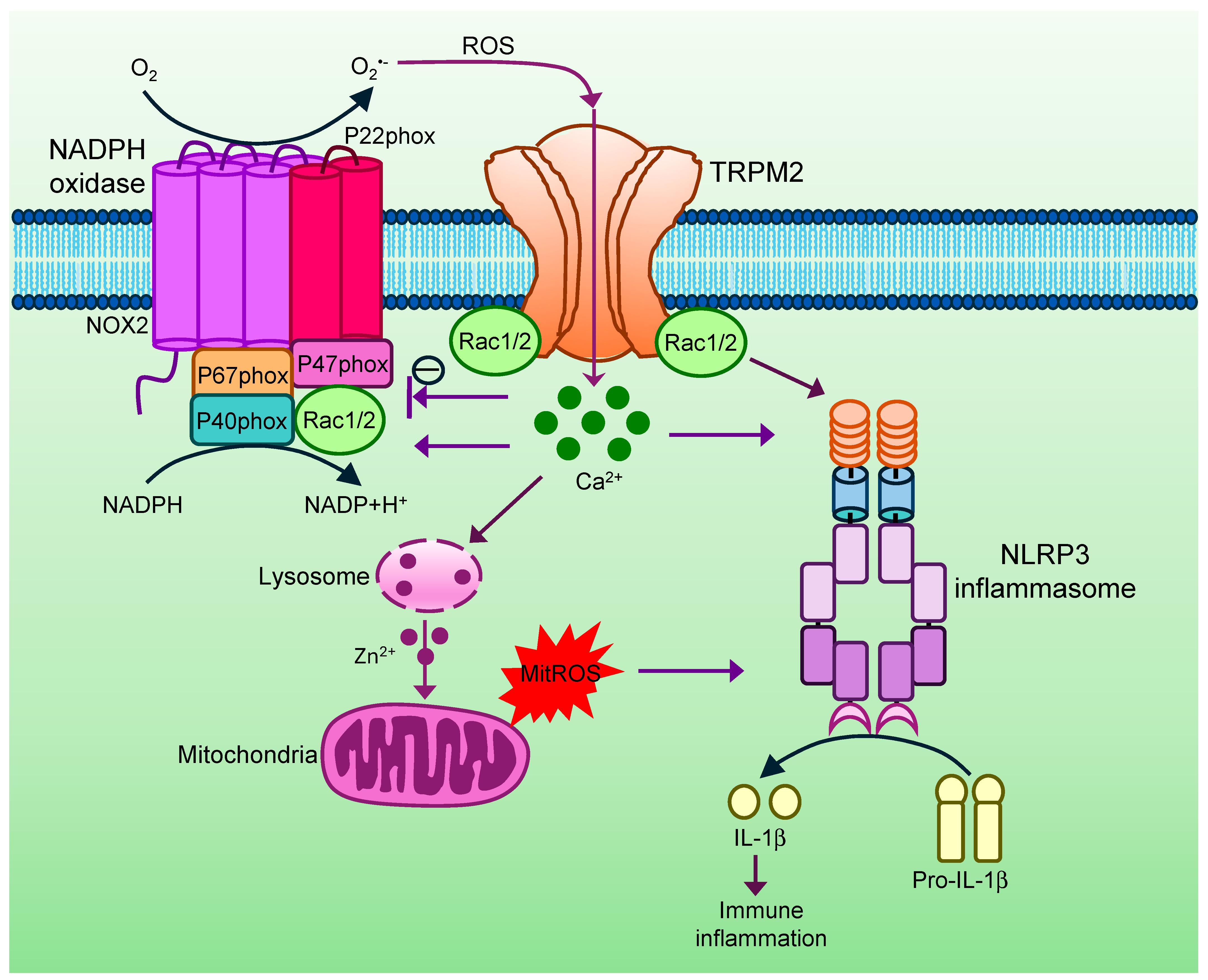

4. TRPM2 in Innate Immunity and Inflammation

5. TRPM2 in Neurological Diseases

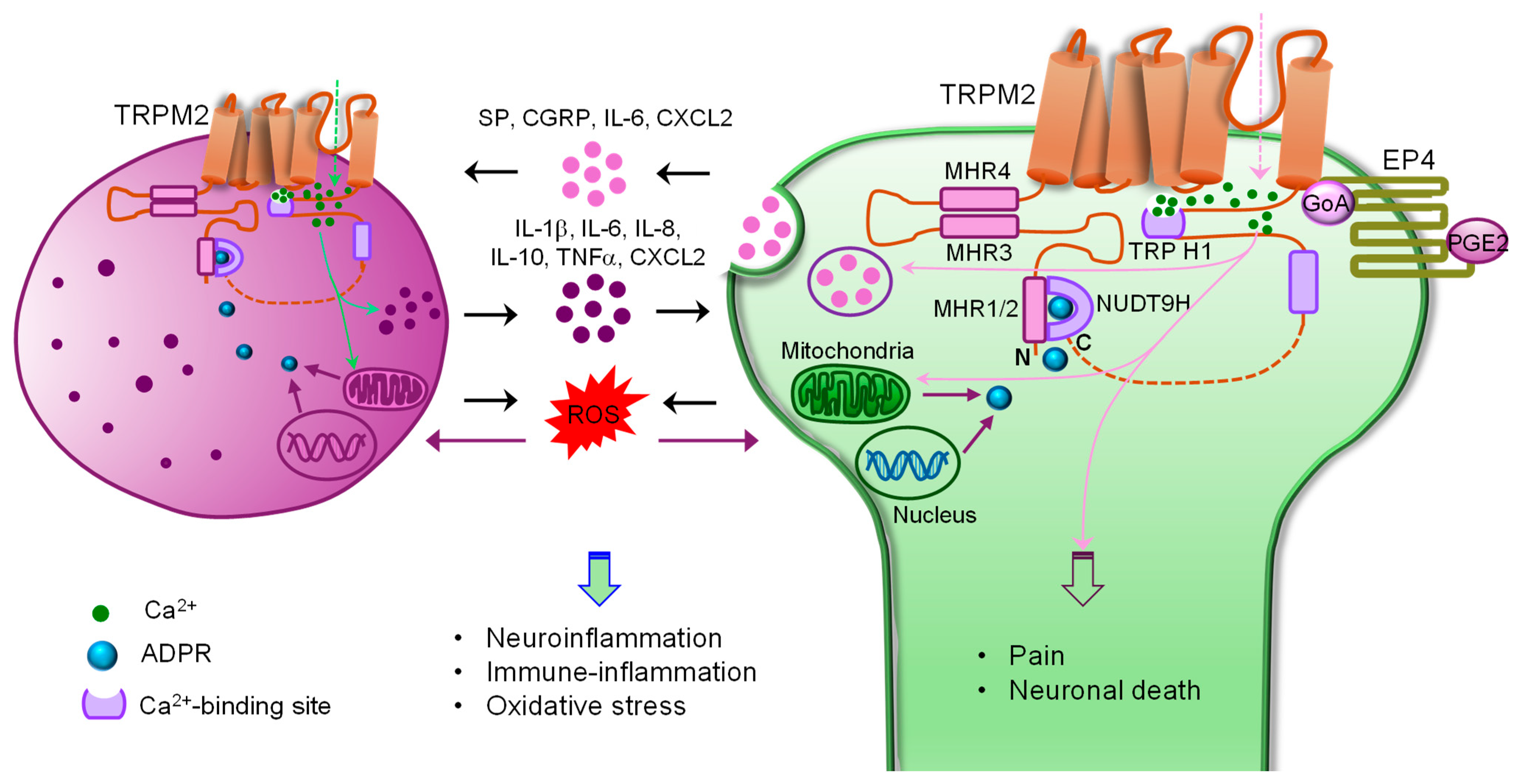

5.1. Chronic Pain

5.1.1. Chronic Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain

5.1.2. Visceral Pain

5.1.3. Migraine

5.2. TRPM2 in Seizure

5.3. TRPM2 in Ischemic Brain Damage (Stroke)

5.4. TRPM2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baral, P.; Udit, S.; Chiu, I.M. Pain and immunity: Implications for host defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, S.; Foster, S.L.; Woolf, C.J. Neuroimmunity: Physiology and Pathology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 34, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Mortadza, S.A.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Jiang, L.H. TRPM2 channel-mediated ROS-sensitive Ca2+ signaling mechanisms in immune cells. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perraud, A.L.; Fleig, A.; Dunn, C.A.; Bagley, L.A.; Launay, P.; Schmitz, C.; Stokes, A.J.; Zhu, Q.; Bessman, M.J.; Penner, R.; et al. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 2001, 411, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.K.; Asgar, J.; Lee, J.; Shim, M.S.; Dumler, C.; Ro, J.Y. The role of TRPM2 in hydrogen peroxide-induced expression of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine in rat trigeminal ganglia. Neuroscience 2015, 297, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, M.E.; Jackson, M.F.; Li, H.; Perez, Y.; Sun, H.S.; Kiyonaka, S.; Mori, Y.; Tymianski, M.; MacDonald, J.F. Ca2+-dependent induction of TRPM2 currents in hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.H.; McNaughton, P.A. The TRPM2 ion channel is required for sensitivity to warmth. Nature 2016, 536, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonfria, E.; Marshall, I.C.; Boyfield, I.; Skaper, S.D.; Hughes, J.P.; Owen, D.E.; Zhang, W.; Miller, B.A.; Benham, C.D.; McNulty, S. Amyloid beta-peptide(1-42) and hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity are mediated by TRPM2 in rat primary striatal cultures. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, R.; Grimm, C.; Grosse, K.; Hoffmann, A.; Sauerbruch, S.; Kettenmann, H.; Schultz, G.; Harteneck, C. Hydrogen peroxide and ADP-ribose induce TRPM2-mediated calcium influx and cation currents in microglia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2004, 286, C129–C137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagamine, K.; Kudoh, J.; Minoshima, S.; Kawasaki, K.; Asakawa, S.; Ito, F.; Shimizu, N. Molecular cloning of a novel putative Ca2+ channel protein (TRPC7) highly expressed in brain. Genomics 1998, 54, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Wakamori, M.; Ishii, M.; Maeno, E.; Nishida, M.; Yoshida, T.; Yamada, H.; Shimizu, S.; Mori, E.; Kudoh, J.; et al. LTRPC2 Ca2+-permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol. Cell 2002, 9, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, K.; Hara, Y.; Tominaga, T.; Higashi, T.; Konishi, Y.; Mori, Y.; Tominaga, M. TRPM2 activation by cyclic ADP-ribose at body temperature is involved in insulin secretion. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Winkler, P.A.; Sun, W.; Lü, W.; Du, J. Architecture of the TRPM2 channel and its activation mechanism by ADP-ribose and calcium. Nature 2018, 562, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Fu, T.-M.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, S.; Greka, A.; Wu, H. Structures and gating mechanism of human TRPM2. Science 2018, 362, eaav4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, B.; Jiang, Y.; Szollosi, A.; Zhang, Z.; Csanady, L. A conserved mechanism couples cytosolic domain movements to pore gating in the TRPM2 channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2415548121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, P.; Lin, Q.; Feng, J.; Yue, L. A systemic review of the integral role of TRPM2 in ischemic stroke: From upstream risk factors to ultimate neuronal death. Cells 2022, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belrose, J.C.; Jackson, M.F. TRPM2: A candidate therapeutic target for treating neurological diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolle, C.; Rack, J.G.; Ziegler, M. NAD and ADP-ribose metabolism in mitochondria. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 3530–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehage, E.; Eisfeld, J.; Heiner, I.; Jüngling, E.; Zitt, C.; Lückhoff, A. Activation of the cation channel long transient receptor potential channel 2 (LTRPC2) by hydrogen peroxide: A splice variant reveals a mode of activation independent of ADP-ribose. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 23150–23156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonfria, E.; Marshall, I.C.; Benham, C.D.; Boyfield, I.; Brown, J.D.; Hill, K.; Hughes, J.P.; Skaper, S.D.; McNulty, S. TRPM2 channel opening in response to oxidative stress is dependent on activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 143, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolisek, M.; Beck, A.; Fleig, A.; Penner, R. Cyclic ADP-ribose and hydrogen peroxide synergize with ADP-ribose in the activation of TRPM2 channels. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perraud, A.L.; Takanishi, C.L.; Shen, B.; Kang, S.; Smith, M.K.; Schmitz, C.; Knowles, H.M.; Ferraris, D.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Accumulation of free ADP-ribose from mitochondria mediates oxidative stress-induced gating of TRPM2 cation channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 6138–6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, B.; Csanády, L. Identification of direct and indirect effectors of the Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 30091–30102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartók, Á.; Csanády, L. Dual amplification strategy turns TRPM2 channels into supersensitive central heat detectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2212378119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buelow, B.; Song, Y.; Scharenberg, A.M. The Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase PARP-1 is required for oxidative stress-induced TRPM2 activation in lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 24571–24583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, S.; Roussel, J.; Andersson, D.C.; Meli, A.C.; Vidal, B.; Blandel, F.; Lanner, J.T.; Le Guennec, J.-Y.; Katz, A.; Westerblad, H.; et al. TNF-α-mediated caspase-8 activation induces ROS production and TRPM2 activation in adult ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 103, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegert, R.; Bauche, A.; Wolf Perez, A.M.; Watt, J.M.; Rozewitz, M.D.; Winzer, R.; Janus, M.; Gu, F.; Rosche, A.; Harneit, A.; et al. 2′-Deoxyadenosine 5′-diphosphoribose is an endogenous TRPM2 superagonist. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Graeff, R.; Yue, J. Roles and mechanisms of the CD38/cyclic adenosine diphosphate ribose/Ca2+ signaling pathway. World J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 5, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Ye, P.; Liu, H.; Xue, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Fang, C.; et al. Direct Gating of the TRPM2 Channel by cADPR via Specific Interactions with the ADPR Binding Pocket. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 3684–3695.e3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riekehr, W.M.; Sander, S.; Pick, J.; Tidow, H.; Bauche, A.; Guse, A.H.; Fliegert, R. cADPR Does Not Activate TRPM2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, D.; Flemming, R.; Xu, S.Z.; Perraud, A.L.; Beech, D.J. Critical intracellular Ca2+ dependence of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11002–11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkus, J.; Beck, A.; Fleig, A.; Penner, R. Regulation of TRPM2 by extra- and intracellular calcium. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007, 130, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Zhang, W.; Conrad, K.; Mostoller, K.; Cheung, J.Y.; Peterson, B.Z.; Miller, B.A. Regulation of the transient receptor potential channel TRPM2 by the Ca2+ sensor calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9076–9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xie, J.; Yue, L. Intracellular calcium activates TRPM2 and its alternative spliced isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7239–7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Toth, B.; Szollosi, A.; Chen, J.; Csanady, L. Structure of a TRPM2 channel in complex with Ca2+ explains unique gating regulation. eLife 2018, 7, e36409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashio, M.; Sokabe, T.; Shintaku, K.; Uematsu, T.; Fukuta, N.; Kobayashi, N.; Mori, Y.; Tominaga, M. Redox signal-mediated sensitization of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) to temperature affects macrophage functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6745–6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El Hay, M.Y.; Kamm, G.B.; Tlaie Boria, A.; Siemens, J. Diverging roles of TRPV1 and TRPM2 in warm-temperature detection. eLife 2025, 13, RP95618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmolinsky, D.A.; Peng, Y.; Pogorzala, L.A.; Rutlin, M.; Hoon, M.A.; Zuker, C.S. Coding and plasticity in the mammalian thermosensory system. Neuron 2016, 92, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, C.; Hoon, M.A.; Chen, X. The coding of cutaneous temperature in the spinal cord. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricio-Montesinos, R.; Schwaller, F.; Udhayachandran, A.; Rau, F.; Walcher, J.; Evangelista, R.; Vriens, J.; Voets, T.; Poulet, J.F.A.; Lewin, G.R. The Sensory Coding of Warm Perception. Neuron 2020, 106, 830–841.e833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Wang, H.; Kamm, G.B.; Pohle, J.; Reis, F.C.; Heppenstall, P.; Wende, H.; Siemens, J. The TRPM2 channel is a hypothalamic heat sensor that limits fever and can drive hypothermia. Science 2016, 353, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Pei, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yan, J.; Qin, L. Transient receptor potential M2 channel in the hypothalamic preoptic area and its impact on thermoregulation during menopause. Ann. Anat.—Anat. Anz. 2023, 250, 152132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamm, G.B.; Boffi, J.C.; Zuza, K.; Nencini, S.; Campos, J.; Schrenk-Siemens, K.; Sonntag, I.; Kabaoğlu, B.; El Hay, M.Y.A.; Schwarz, Y.; et al. A synaptic temperature sensor for body cooling. Neuron 2021, 109, 3283–3297.e3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Field, R.L.; Ye, D.; Hu, Z.; Xu, K.; Xu, L.; Gong, Y.; Yue, Y.; Kravitz, A.V.; et al. Induction of a torpor-like hypothermic and hypometabolic state in rodents by ultrasound. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Halanobis, A.; Byeon, E.H.; Park, N.H.; Park, S.W.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, D.; Kim, D.R.; Yang, J.; Choe, E.S.; et al. The potential role of hypothalamic POMC(TRPM2) in interscapular BAT thermogenesis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 2040–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzi, A.; Heine, M.; Spinelli, S.; Salis, A.; Worthmann, A.; Diercks, B.; Astigiano, C.; Pérez Mato, R.; Memushaj, A.; Sturla, L.; et al. The TRPM2 ion channel regulates metabolic and thermogenic adaptations in adipose tissue of cold-exposed mice. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1251351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Shimizu, S.; Kiyonaka, S.; Takahashi, N.; Wajima, T.; Hara, Y.; Negoro, T.; Hiroi, T.; Kiuchi, Y.; Okada, T.; et al. TRPM2-mediated Ca2+ influx induces chemokine production in monocytes that aggravates inflammatory neutrophil infiltration. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrhahn, J.; Kraft, R.; Harteneck, C.; Hauschildt, S. Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 is required for lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 2386–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Liang, S.; Mori, Y.; Han, R.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Qiao, L. TRPM2 links oxidative stress to NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Wang, W.; Tadagavadi, R.K.; Briley, N.E.; Love, M.I.; Miller, B.A.; Reeves, W.B. TRPM2 mediates ischemic kidney injury and oxidant stress through RAC1. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 4989–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doye, A.; Chaintreuil, P.; Lagresle-Peyrou, C.; Batistic, L.; Marion, V.; Munro, P.; Loubatier, C.; Chirara, R.; Sorel, N.; Bessot, B.; et al. RAC2 gain-of-function variants causing inborn error of immunity drive NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20231562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, C.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, J.; Wang, M.; Xiang, J.; Sun, D.; Zhou, X. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by RAC1 mediates a new mechanism in diabetic nephropathy. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 71, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Yasuda, H.; Mori, Y.; Kato, S. Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 is involved in trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced acute and chronic colitis-associated fibrosis progression in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 154, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huang, W.; Ma, Y. Down-regulation of TRPM2 attenuates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury through activation of autophagy and inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 104, 108443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida-Sanchez, S.; Gasser, A.; Fliegert, R.; Siebrands, C.C.; Dammermann, W.; Shi, G.; Mousseau, B.J.; Sumoza-Toledo, A.; Bhagat, H.; Walseth, T.F.; et al. Chemotaxis of mouse bone marrow neutrophils and dendritic cells is controlled by adp-ribose, the major product generated by the CD38 enzyme reaction. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 7827–7839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, H.; Luqman, S.; Tan, C.H.; Swann, V.; McNaughton, P.A. TRPM2 ion channels steer neutrophils towards a source of hydrogen peroxide. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Chu, T.; Yang, H.; Wen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Herrmann, M. Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 regulates neutrophil extracellular traps formation and delays resolution of neutrophil-driven sterile inflammation. J. Inflamm. 2023, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAhmad, M.; Shitaw, E.E.; Sivaprasadarao, A. A TRPM2-driven signalling cycle orchestrates abnormal inter-organelle crosstalk in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliougina, M.; El Hiani, Y. TRPM2: Bridging calcium and ROS signaling pathways-implications for human diseases. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1217828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, H.; Heizer, J.W.; Li, Y.; Chapman, K.; Ogden, C.A.; Andreasen, K.; Shapland, E.; Kucera, G.; Mogan, J.; Humann, J.; et al. Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) ion channel is required for innate immunity against Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11578–11583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Dhar, R.; Liu, J.; Hong, S.; Tang, H.; Qian, X. TRPM2 deficiency contributes to M2b macrophage polarization via the PI3K/AKT/CREB pathway in murine sepsis. Innate Immun. 2025, 31, 17534259251343377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Cao, L.; Liu, X.; Sieracki, N.A.; Di, A.; Wen, X.; Chen, Y.; Taylor, S.; Huang, X.; Tiruppathi, C.; et al. Oxidant sensing by TRPM2 inhibits neutrophil migration and mitigates inflammation. Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, H.; Li, Y.; Perraud, A.L. The TRPM2 ion channel, an oxidative stress and metabolic sensor regulating innate immunity and inflammation. Immunol. Res. 2013, 55, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Shalygin, A.; Gudermann, T.; Chubanov, V.; Dietrich, A. TRPM2 channels are essential for regulation of cytokine production in lung interstitial macrophages. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, A.; Gao, X.P.; Qian, F.; Kawamura, T.; Han, J.; Hecquet, C.; Ye, R.D.; Vogel, S.M.; Malik, A.B. The redox-sensitive cation channel TRPM2 modulates phagocyte ROS production and inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robledo-Avila, F.H.; Ruiz-Rosado, J.D.; Brockman, K.L.; Partida-Sánchez, S. The TRPM2 ion channel regulates inflammatory functions of neutrophils during Listeria monocytogenes infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beceiro, S.; Radin, J.N.; Chatuvedi, R.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Horvarth, D.J.; Cortado, H.; Gu, Y.; Dixon, B.; Gu, C.; Lange, I.; et al. TRPM2 ion channels regulate macrophage polarization and gastric inflammation during Helicobacter pylori infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, S.B.; La Russa, F.; Bennett, D.L. Crosstalk between the nociceptive and immune systems in host defence and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, K.; Haraguchi, K.; Asakura, K.; Isami, K.; Sakimoto, S.; Shirakawa, H.; Mori, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Kaneko, S. Involvement of TRPM2 in a wide range of inflammatory and neuropathic pain mouse models. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 127, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, K.; Kawamoto, A.; Isami, K.; Maeda, S.; Kusano, A.; Asakura, K.; Shirakawa, H.; Mori, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Kaneko, S. TRPM2 contributes to inflammatory and neuropathic pain through the aggravation of pronociceptive inflammatory responses in mice. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 3931–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayir, M.H.; Yıldızhan, K.; Altındağ, F. Effect of Hesperidin on Sciatic Nerve Damage in STZ-Induced Diabetic Neuropathy: Modulation of TRPM2 Channel. Neurotox. Res. 2023, 41, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isami, K.; Haraguchi, K.; So, K.; Asakura, K.; Shirakawa, H.; Mori, Y.; Nakagawa, T.; Kaneko, S. Involvement of TRPM2 in peripheral nerve injury-induced infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the spinal cord in mouse neuropathic pain model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, L.; Alizada, M.; Yang, J.; Feng, Y.; Malhotra, M.; Zhang, X. TRPM2 is a direct pain transducer. bioRxiv, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Takagi, K.; Kato, A.; Ishibashi, T.; Mori, Y.; Tashima, K.; Mitsumoto, A.; Kato, S.; Horie, S. Role of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channels in visceral nociception and hypersensitivity. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 285, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhara, K.K.; Rossen, N.D.; Deng, F.; Castro, J.; Harrington, A.M.; Chu, T.; Garcia-Caraballo, S.; Brizuela, M.; O’Donnell, T.; Xu, J.; et al. Topological segregation of stress sensors along the gut crypt-villus axis. Nature 2025, 640, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Song, Y.; Chong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Gastrodin alleviates NTG-induced migraine-like pain via inhibiting succinate/HIF-1α/TRPM2 signaling pathway in trigeminal ganglion. Phytomedicine 2024, 125, 155266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazğan, Y.; Nazıroğlu, M. Involvement of TRPM2 in the neurobiology of experimental migraine: Focus on oxidative stress and apoptosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 5581–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ye, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, N.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Xi, J.; Chen, L.; Xu, C.; et al. Microglial transient receptor potential melastatin 2 deficiency accelerates seizure development via increasing AMPAR-mediated neuronal excitability. MedComm 2025, 6, e70271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jackson, M.F.; Xie, Y.F. Glia and TRPM2 channels in plasticity of central nervous system and Alzheimer’s diseases. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 1680905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malko, P.; Syed Mortadza, S.A.; McWilliam, J.; Jiang, L.-H. TRPM2 channel in microglia as a new player in neuroinflammation associated with a spectrum of central nervous system pathologies. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, T.; Gong, L.; Hu, Z.; Wei, H.; Fan, J.; Lin, D.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Dong, X.; et al. Trpm2 deficiency in microglia attenuates neuroinflammation during epileptogenesis by upregulating autophagy via the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 186, 106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.F.; Feng, Z.P.; Sun, H.S.; Britto, L.R.G. Microglial activation and inflammatory responses in Parkinson’s disease models are attenuated by TRPM2 depletion. Glia 2025, 73, 2035–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F.F.; Ulrich, H.; Feng, Z.P.; Sun, H.S.; Britto, L.R. Neurodegeneration and glial morphological changes are both prevented by TRPM2 inhibition during the progression of a Parkinson’s disease mouse model. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 377, 114780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, S.; Kawakami, S.; Hara, Y.; Wakamori, M.; Itoh, E.; Minami, T.; Takada, Y.; Kume, T.; Katsuki, H.; Mori, Y.; et al. A critical role of TRPM2 in neuronal cell death by hydrogen peroxide. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 101, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Yang, W.; Ainscough, J.F.; Hu, X.P.; Li, X.; Sedo, A.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.M.; et al. TRPM2 channel deficiency prevents delayed cytosolic Zn2+ accumulation and CA1 pyramidal neuronal death after transient global ischemia. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W.; Gong, L.N.; Lai, K.; Yu, X.F.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, M.X.; Yin, X.L.; Liang, M.; Shi, H.S.; Jiang, L.H.; et al. Bilirubin gates the TRPM2 channel as a direct agonist to exacerbate ischemic brain damage. Neuron 2023, 111, 1609–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, P.; Feng, J.; Yue, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, G.; Sun, B.; He, Y.; Miller, B.; Yu, A.S.; Su, Z.; et al. Functional coupling of TRPM2 and extrasynaptic NMDARs exacerbates excitotoxicity in ischemic brain injury. Neuron 2022, 110, 1944–1958.e1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, P.; Feng, J.; Legere, N.; Li, Y.; Yue, Z.; Li, C.X.; Mori, Y.; Miller, B.; Hao, B.; Yue, L. TRPM2 enhances ischemic excitotoxicity by associating with PKCγ. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnham, K.J.; Masters, C.L.; Bush, A.I. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Fang, Q.; Hu, X.; Zou, W.; Huang, M.; Ke, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Cai, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. TRPM2 as a conserved gatekeeper determines the vulnerability of DA neurons by mediating ROS sensing and calcium dyshomeostasis. Prog. Neurobiol. 2023, 231, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çınar, R.; Nazıroğlu, M. TRPM2 channel inhibition attenuates amyloid β42-induced apoptosis and oxidative stress in the hippocampus of mice. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 1335–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapchenko, V.G.; Chen, M.; Guzman, M.S.; Xie, Y.F.; Lavine, N.; Fan, J.; Beraldo, F.H.; Martyn, A.C.; Belrose, J.C.; Mori, Y.; et al. The transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channel contributes to β-amyloid oligomer-related neurotoxicity and memory impairment. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 15157–15169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawieyah Syed Mortadza, S.; Sim, J.A.; Neubrand, V.E.; Jiang, L.H. A critical role of TRPM2 channel in Aβ(42) -induced microglial activation and generation of tumor necrosis factor-α. Glia 2018, 66, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.K.; Kho, A.R.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Kang, B.S.; Kang, D.H.; Park, M.K.; Park, K.H.; Lim, M.S.; Choi, B.Y.; et al. Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) inhibition by antioxidant, N-acetyl-l-cysteine, reduces global cerebral ioschemia-induced neuronal death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, A.-P.; Voets, T.; Iadarola, M.J.; Szallasi, A. Targeting TRP channels for pain relief: A review of current evidence from bench to bedside. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2024, 75, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Patra, P.H.; Somerfield, H.; Benya-Aphikul, H.; Upadhya, M.; Zhang, X. IQGAP1 promotes chronic pain by regulating the trafficking and sensitization of TRPA1 channels. Brain 2023, 146, 2595–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vriens, J.; Owsianik, G.; Hofmann, T.; Philipp, S.E.; Stab, J.; Chen, X.; Benoit, M.; Xue, F.; Janssens, A.; Kerselaers, S.; et al. TRPM3 is a nociceptor channel involved in the detection of noxious heat. Neuron 2011, 70, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Yudin, Y.; Kim, N.; Tao, Y.X.; Rohacs, T. TRPM3 channels play roles in heat hypersensitivity and spontaneous pain after nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 2457–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.-C.; Han, W.-J.; Dou, Z.-W.; Lu, N.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.-D.; Ma, S.-B.; Tian, Z.-C.; Xian, H.; Liu, W.-N.; et al. TRPC3/6 channels mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity via enhancement of nociceptor excitability and of spinal synaptic transmission. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2404342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobori, S.; Tamada, K.; Uemura, N.; Sawada, K.; Kakae, M.; Nagayasu, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Mori, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Shirakawa, H. Spinal TRPC3 promotes neuropathic pain and coordinates phospholipase C–induced mechanical hypersensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2416828122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K.E.; Moehring, F.; Shiers, S.I.; Laskowski, L.J.; Mikesell, A.R.; Plautz, Z.R.; Brezinski, A.N.; Mecca, C.M.; Dussor, G.; Price, T.J.; et al. Transient receptor potential canonical 5 mediates inflammatory mechanical and spontaneous pain in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabd7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Pritišanac, I.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Liu, H.-W.; Gong, L.-N.; Li, M.-X.; Lu, J.-F.; Qi, X.; Xu, T.-L.; Forman-Kay, J.; et al. Glutamate acts on acid-sensing ion channels to worsen ischaemic brain injury. Nature 2024, 631, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A. TRPM2 in Cancer. Cell Calcium 2019, 80, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-S.; Ren, H.-C.; Li, H.; Xing, M.; Cao, J.-H. From oxidative stress to metabolic dysfunction: The role of TRPM2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 284, 138081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Fan, R.; Song, Z.; Li, Z.; Gan, H.; Fan, H. Clusterin regulates TRPM2 to protect against myocardial injury induced by acute myocardial infarction injury. Tissue Cell 2023, 82, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, E.S.; Rychkov, G.Y.; Barritt, G.J. TRPM2 non-selective cation channels in liver injury mediated by reactive oxygen species. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Qu, C.; Rao, Z.; Wu, D.; Zhao, J. Bidirectional regulation mechanism of TRPM2 channel: Role in oxidative stress, inflammation and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1391355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Malhotra, M. Neuroimmune Regulation by TRPM2 Channels. Cells 2026, 15, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010076

Zhang X, Malhotra M. Neuroimmune Regulation by TRPM2 Channels. Cells. 2026; 15(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xuming, and Mitali Malhotra. 2026. "Neuroimmune Regulation by TRPM2 Channels" Cells 15, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010076

APA StyleZhang, X., & Malhotra, M. (2026). Neuroimmune Regulation by TRPM2 Channels. Cells, 15(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010076