Absorption of Energy in Excess, Photoinhibition, Transpiration, and Foliar Heat Emission Feedback Loops During Global Warming

Highlights

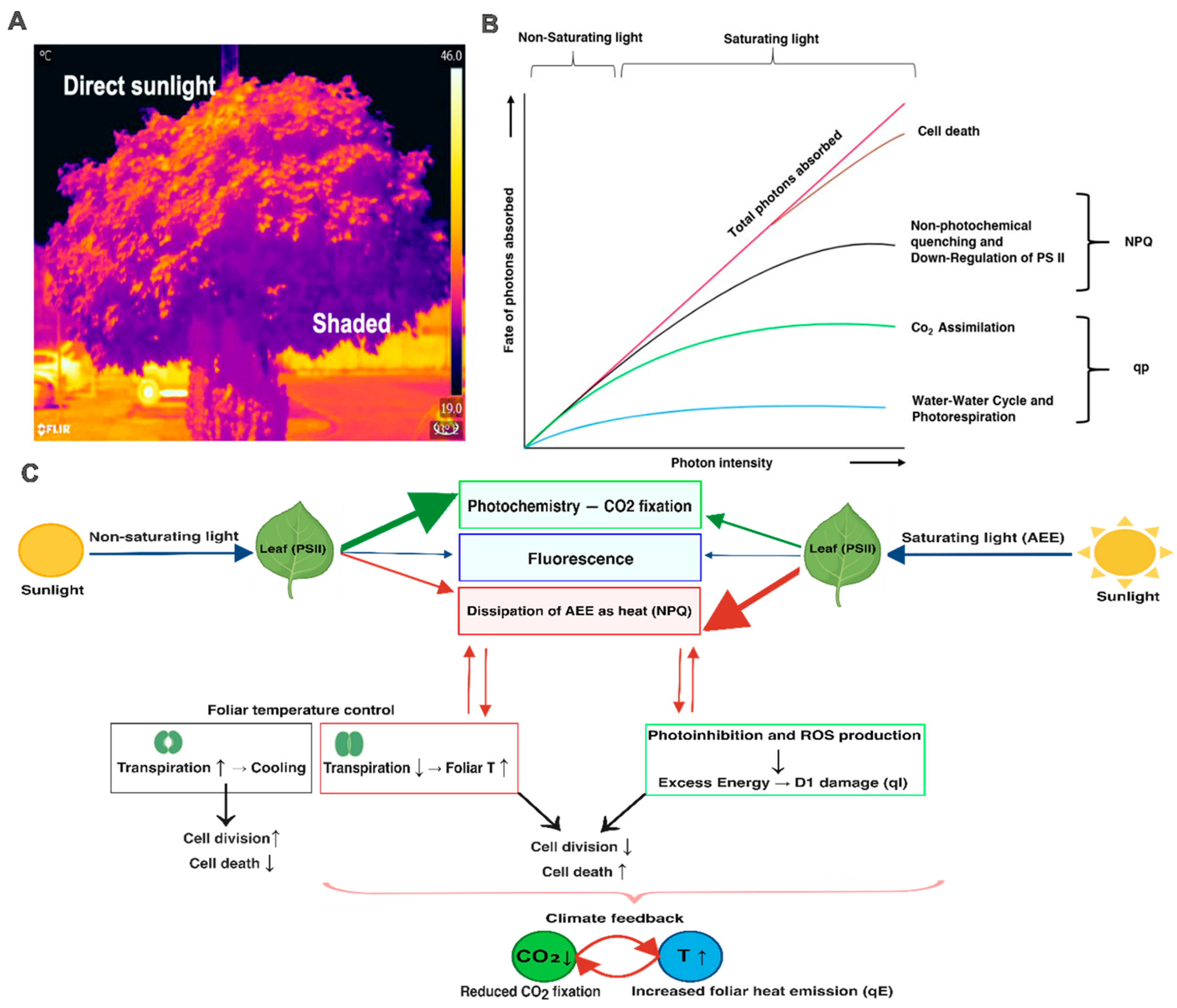

- Foliar temperature response during excess light stress is the result of a dynamic interplay between NPQ, qE, photochemistry, and transpiration rather than of any single mechanism. Thus, spatial and temporal heterogeneity of leaf temperature arises from the physiological state and absorbed energy fate balance.

- Conditionally, the ratio between these processes can vary, thus increasing or decreasing foliar heat emission and warming up or cooling down the surrounding environment.

- Constraints imposed by global warming and drought can further disrupt this balance, increasing the risk of foliar heat stress and cell death induction.

- Leaf-internal energy redistribution represents an important but often simplified and ignored component of foliar thermoregulation under excess light and climate warming.

- Explicit consideration of these interactions may improve understanding and modelling of plant–climate feedbacks under future warming scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

Global Warming Impacts on Environmental Stability

2. Thermoregulation in Plants

3. Non-Photochemical Quenching and Foliar Temperature Regulation

4. Passive and Active Mechanisms of Plant Thermotolerance

4.1. Phytohormonal Regulation of Heat Stress Responses

4.2. Xanthophyll Cycle Pigments and Regulated Thermal Energy Dissipation

4.3. Calcium, ROS, and Heat Shock Signaling Networks

4.4. Transcriptional Control of Thermotolerance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. More than Taking the Heat: Crops and Global Change. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururani, M.A.; Venkatesh, J.; Tran, L.S.P. Regulation of Photosynthesis during Abiotic Stress-Induced Photoinhibition. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Cui, K.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Fahad, S.; Hu, Q.; Huang, J.; Nie, L.; Mohapatra, P.K.; Peng, S. Heat-Induced Cytokinin Transportation and Degradation Are Associated with Reduced Panicle Cytokinin Expression and Fewer Spikelets per Panicle in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case, M.J.; Johnson, B.G.; Bartowitz, K.J.; Hudiburg, T.W. Forests of the Future: Climate Change Impacts and Implications for Carbon Storage in the Pacific Northwest, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 482, 118886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Frenne, P.; Lenoir, J.; Luoto, M.; Scheffers, B.R.; Zellweger, F.; Aalto, J.; Ashcroft, M.B.; Christiansen, D.M.; Decocq, G.; De Pauw, K. Forest Microclimates and Climate Change: Importance, Drivers and Future Research Agenda. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2279–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ort, D.R.; Merchant, S.S.; Alric, J.; Barkan, A.; Blankenship, R.E.; Bock, R.; Croce, R.; Hanson, M.R.; Hibberd, J.M.; Long, S.P. Redesigning Photosynthesis to Sustainably Meet Global Food and Bioenergy Demand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8529–8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M.E.; Gleadow, R.M.; Dalling, M.J. Effects of Drought and High Temperature on Grain Growth in Wheat. Funct. Plant Biol. 1984, 11, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, R.; Nicolas, M.E. Effects of Short Periods of Drought and High Temperature on Grain Growth and Starch Accumulation of Two Malting Barley Cultivars. Funct. Plant Biol. 1996, 23, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, V.; Behl, R. Grain Yield in Wheat as Affected by Short Periods of High Temperature, Drought and Their Interaction during Pre-and Post-Anthesis Stages. Cereal Res. Commun. 2010, 38, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Kjellstrom, T.; Atar, D.; Sharma, P.; Kayastha, B.; Bhandari, G.; Pradhan, P.K. Heat Stress Impacts on Cardiac Mortality in Nepali Migrant Workers in Qatar. Cardiology 2019, 143, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 92-9169-164-X. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Carlson, J.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.S.; Doyle, J.C.; Harrison, S.P.; et al. Fire in the Earth System. Science 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Ahlström, A.; Hobbie, S.E.; Reich, P.B.; Nieradzik, L.P.; Staver, A.C.; Scharenbroch, B.C.; Jumpponen, A.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Randerson, J.T.; et al. Fire Frequency Drives Decadal Changes in Soil Carbon and Nitrogen and Ecosystem Productivity. Nature 2018, 553, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedinmyer, C.; Yokelson, R.J.; Gullett, B.K. Global Emissions of Trace Gases, Particulate Matter, and Hazardous Air Pollutants from Open Burning of Domestic Waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 9523–9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, X.J.; Rogers, B.M.; Veraverbeke, S.; Johnstone, J.F.; Baltzer, J.L.; Barrett, K.; Bourgeau-Chavez, L.; Day, N.J.; de Groot, W.J.; Dieleman, C.M.; et al. Fuel Availability Not Fire Weather Controls Boreal Wildfire Severity and Carbon Emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Hobbie, S.E.; Reich, P.B.; Jumpponen, A.; Brookshire, E.N.J.; Caprio, A.C.; Coetsee, C.; Jackson, R.B. Repeated Fire Shifts Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling by Changing Plant Inputs and Soil Decomposition Across Ecosystems. Ecol. Monogr. 2020, 90, e01409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Veraverbeke, S.; Andela, N.; Lasslop, G.; Forkel, M.; Smith, A.J.; Burton, C.; Betts, R.A.; van der Werf, G.R. Global and Regional Trends and Drivers of Fire Under Climate Change. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2020RG000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.; Baldi, A.; Buda, V.; Carli, B.; Cudlin, P.; Jones, M.B.; Korhola, A.; Michalski, R.; Novo, F.; Oszlányi, J. Serious Mismatches Continue Between Science and Policy in Forest Bioenergy. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.C.; Viola, E. Catastrophic Climate Risk and Brazilian Amazonian Politics and Policies: A New Research Agenda. Glob. Environ. Politics 2019, 19, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brando, P.; Macedo, M.; Silvério, D.; Rattis, L.; Paolucci, L.; Alencar, A.; Coe, M.; Amorim, C. Amazon Wildfires: Scenes from a Foreseeable Disaster. Flora 2020, 268, 151609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.V.; Basso, L.S.; Miller, J.B.; Gloor, M.; Gatti Domingues, L.; Cassol, H.L.; Tejada, G.; Aragão, L.E.; Nobre, C.; Peters, W. Amazonia as a Carbon Source Linked to Deforestation and Climate Change. Nature 2021, 595, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Sarlöv-Herlin, I.; Knez, I.; Ångman, E.; Ode Sang, Å.; Åkerskog, A. Landscape Identity, Before and After a Forest Fire. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Qiao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, J.; Meng, Q.; Su, G.; Zhong, S.; Wang, F. Wildfire Risk Assessment Using Deep Learning in Guangdong Province, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.W.; Kelley, D.I.; Burton, C.A.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Barbosa, M.L.F.; Brambleby, E.; Hartley, A.J.; Lombardi, A.; Mataveli, G.; McNorton, J.R. State of Wildfires 2023–2024. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 3601–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayedi, S.S.; Abbott, B.W.; Vannière, B.; Leys, B.; Colombaroli, D.; Romera, G.G.; Słowiński, M.; Aleman, J.C.; Blarquez, O.; Feurdean, A. Assessing Changes in Global Fire Regimes. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, P.; Ceder, L.A.; Astrup, R.; Binkley, D.; Dalsgaard, L.; Egnell, G.; Filipchuk, A.; Genet, H.; Ilintsev, A.; Kurz, W.A.; et al. Sustainable Boreal Forest Management Challenges and Opportunities for Climate Change Mitigation; International Boreal Forest Research Association (IBFRA): Québec City, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kikstra, J.S.; Nicholls, Z.R.J.; Smith, C.J.; Lewis, J.; Lamboll, R.D.; Byers, E.; Sandstad, M.; Meinshausen, M.; Gidden, M.J.; Rogelj, J.; et al. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report WGIII Climate Assessment of Mitigation Pathways: From Emissions to Global Temperatures. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 9075–9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Trugman, A.T.; Badgley, G.; Anderson, C.M.; Bartuska, A.; Ciais, P.; Cullenward, D.; Field, C.B.; Freeman, J.; Goetz, S.J.; et al. Climate-Driven Risks to the Climate Mitigation Potential of Forests. Science 2020, 368, eaaz7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.P.; Sullivan, D.S.; Klenner, W. Fate of Postharvest Woody Debris, Mammal Habitat, and Alternative Management of Forest Residues on Clearcuts: A Synthesis. Forests 2021, 12, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, O.J.L. Heat and Drought Responses of Tropical Trees in a Warming World; GUPEA: Online, 2024; ISBN 978-91-8115-048-3. [Google Scholar]

- Spracklen, D.V.; Baker, J.C.A.; Garcia-Carreras, L.; Marsham, J.H. The Effects of Tropical Vegetation on Rainfall. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a Cultivated Planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kitudom, N.; Fauset, S.; Slot, M.; Fan, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Lin, H. Leaf Thermal Regulation Strategies of Canopy Species across Four Vegetation Types along a Temperature and Precipitation Gradient. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 343, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulasek, M.; Bernacki, M.J.; Ciszak, K.; Witoń, D.; Karpiński, S. Contribution of PsbS Function and Stomatal Conductance to Foliar Temperature in Higher Plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 1495–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrin Ghalami, R.; Duszyn, M.; Kamran, M.; Burdiak, P.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S.M. Transpiration, Photoinhibition and Non-Photochemical Quenching Reciprocally Control Foliar Heat Emission. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat Tolerance in Plants: An Overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S.L.; Collins, B.M.; Fettig, C.J.; Finney, M.A.; Hoffman, C.M.; Knapp, E.E.; North, M.P.; Safford, H.; Wayman, R.B. Drought, Tree Mortality, and Wildfire in Forests Adapted to Frequent Fire. BioScience 2018, 68, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffani, D.S.; Rognon, P.; Farquhar, G.D. The Role of Thermodiffusion in Transpiration. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Kim, E.; Minagawa, J.; Takizawa, K. How Much Heat Does Non-Photochemical Quenching Produce? Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1367795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, C.J.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Safeguarding Crop Photosynthesis in a Rapidly Warming World. Science 2025, 388, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.E.; Hu, J.; Michaletz, S.T. Scaling Plant Responses to Heat: From Molecules to the Biosphere. Science 2025, 388, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, D.M. Transpiration and Leaf Temperature. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1968, 19, 211–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan Brown, W.; Gloor, E.; Fyfe, R.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Harper, N.J.; Ganderton, P.; Hart, K.; Curioni, G.; Quick, S.; Davidson, S.J.; et al. Elevated CO2 Increases the Canopy Temperature of Mature Quercus Robur (Pedunculate oak). Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, O.J.L.; Wittemann, M.; Dusenge, M.E.; Habimana, J.; Manishimwe, A.; Mujawamariya, M.; Ntirugulirwa, B.; Zibera, E.; Tarvainen, L.; Nsabimana, D.; et al. Canopy Temperatures Strongly Overestimate Leaf Thermal Safety Margins of Tropical Trees. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 2115–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, J.R.; Grant, N.M.; Miller, R.E.; Robinson, S.A. Mechanisms of Thermoregulation in Plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletz, S.T.; Weiser, M.D.; Zhou, J.; Kaspari, M.; Helliker, B.R.; Enquist, B.J. Plant Thermoregulation: Energetics, Trait–Environment Interactions, and Carbon Economics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaletz, S.T.; Weiser, M.D.; McDowell, N.G.; Zhou, J.; Kaspari, M.; Helliker, B.R.; Enquist, B.J. The Energetic and Carbon Economic Origins of Leaf Thermoregulation. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Burdiak, P.; Karpiński, S. Crosstalk Between Abiotic and Biotic Stresses Responses and the Role of Chloroplast Retrograde Signaling in the Cross-Tolerance Phenomena in Plants. Cells 2025, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umekawa, Y.; Seymour, R.S.; Ito, K. The Biochemical Basis for Thermoregulation in Heat-Producing Flowers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikkanen, M.; Aro, E.-M. Integrative Regulatory Network of Plant Thylakoid Energy Transduction. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, D.; Miyao, M.; Murata, N. Heat Inactivation of Oxygen Evolution in Photosystem II Particles and Its Acceleration by Chloride Depletion and Exogenous Manganese. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Bioenerg. 1985, 807, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.; Bjorkman, O. Photosynthetic Response and Adaptation to Temperature in Higher Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1980, 31, 491–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.V. Nonphotochemical Chlorophyll Fluorescence Quenching: Mechanism and Effectiveness in Protecting Plants from Photodamage. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.V. The Mechanism of Nonphotochemical Quenching: The End of the Ongoing Debate. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asada, K. The Water-Water Cycle in Chloroplasts: Scavenging of Active Oxygens and Dissipation of Excess Photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1999, 50, 601–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.R. Chlorophyll Fluorescence: A Probe of Photosynthesis In Vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszak, K.; Kulasek, M.; Barczak, A.; Grzelak, J.; Maćkowski, S.; Karpiński, S. PsbS Is Required for Systemic Acquired Acclimation and Post-Excess-Light-Stress Optimization of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Decay Times in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2015, 10, e982018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoń, D.; Sujkowska-Rybkowska, M.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Czarnocka, W.; Bernacki, M.; Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Karpiński, S. MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 4 Impacts Leaf Development, Temperature, and Stomatal Movement in Hybrid Aspen. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 2190–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.; Ingwers, M.; McGuire, M.A.; Teskey, R.O. Stomatal Conductance Increases with Rising Temperature. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017, 12, e1356534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Bauwe, H.; Badger, M. Impairment of the Photorespiratory Pathway Accelerates Photoinhibition of Photosystem II by Suppression of Repair but Not Acceleration of Damage Processes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A.J.; Ware, M.A.; Ruban, A.V. Dynamic Interplay between Photodamage and Photoprotection in Photosystem II. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1098–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, M.; Pinnola, A.; Gordon, S.C.; Bassi, R.; Schlau-Cohen, G.S. Observation of Dissipative Chlorophyll-to-Carotenoid Energy Transfer in Light-Harvesting Complex II in Membrane Nanodiscs. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Sakowska, K.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Pacheco-Labrador, J.; van der Tol, C.; Porcar-Castell, A.; Magney, T.S.; Carrara, A.; Colombo, R.; El-Madany, T.S.; et al. Heatwave Breaks down the Linearity between Sun-Induced Fluorescence and Gross Primary Production. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 2415–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antala, M.; Juszczak, R.; Rastogi, A. Nonphotochemical Quenching Does Not Alter the Relationship between Sun-Induced Fluorescence and Gross Primary Production Under Heatwave. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Kruk, J.; Górecka, M.; Karpińska, B.; Karpiński, S. Evidence for Light Wavelength-Specific Photoelectrophysiological Signaling and Memory of Excess Light Episodes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.S.; Sureshkumar, S.; Sinha, A.K.; Balasubramanian, S. Dispersed Components Drive Temperature Sensing and Response in Plants. Science 2025, 388, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromdijk, J.; Głowacka, K.; Leonelli, L.; Gabilly, S.T.; Iwai, M.; Niyogi, K.K.; Long, S.P. Improving Photosynthesis and Crop Productivity by Accelerating Recovery from Photoprotection. Science 2016, 354, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amerongen, H.; Croce, R. Nonphotochemical Quenching in Plants: Mechanisms and Mysteries. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, G. Non-photochemical Quenching (NPQ) in Photoprotection: Insights into NPQ Levels Required to Avoid Photoinactivation and Photoinhibition. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, G.; Yasmin, M.; Liran, O.; Hanna, R.; Kleifeld, O.; Horev, G.; Wollman, F.-A.; Schuster, G.; Nawrocki, W.J. Processes Independent of Nonphotochemical Quenching Protect a High-Light-Tolerant Desert Alga from Oxidative Stress. Plant Physiol. 2024, 197, kiae608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.; Li, X.-P.; Niyogi, K.K. Non-Photochemical Quenching. A Response to Excess Light Energy. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murchie, E.H.; Niyogi, K.K. Manipulation of Photoprotection to Improve Plant Photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-P.; Gilmore, A.M.; Niyogi, K.K. Molecular and Global Time-Resolved Analysis of a Psbsgene Dosage Effect on pH-and Xanthophyll Cycle-Dependent Nonphotochemical Quenching in Photosystem II. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 33590–33597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-P.; BjoÈrkman, O.; Shih, C.; Grossman, A.R.; Rosenquist, M.; Jansson, S.; Niyogi, K.K. A Pigment-Binding Protein Essential for Regulation of Photosynthetic Light Harvesting. Nature 2000, 403, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, R.; Dall’Osto, L. Dissipation of Light Energy Absorbed in Excess: The Molecular Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdiak, P.; Mielecki, J.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. The CRK5 and WRKY53 Are Conditional Regulators of Senescence and Stomatal Conductance in Arabidopsis. Cells 2022, 11, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaňa, R.; Vass, I. Thermoimaging as a Tool for Studying Light-Induced Heating of Leaves: Correlation of Heat Dissipation with the Efficiency of Photosystem II Photochemistry and Non-Photochemical Quenching. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008, 64, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarathunge, D.P.; Medlyn, B.E.; Drake, J.E.; De Kauwe, M.G.; Tjoelker, M.G.; Aspinwall, M.J.; Barton, C.V.M.; Campany, C.E.; Crous, K.Y.; Yang, J.; et al. Photosynthetic Temperature Responses in Leaves and Canopies: Why Temperature Optima May Disagree at Different Scales. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpae135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilroy, S.; Białasek, M.; Suzuki, N.; Górecka, M.; Devireddy, A.R.; Karpiński, S.; Mittler, R. ROS, Calcium, and Electric Signals: Key Mediators of Rapid Systemic Signaling in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białasek, M.; Górecka, M.; Mittler, R.; Karpiński, S. Evidence for the Involvement of Electrical, Calcium and ROS Signaling in the Systemic Regulation of Non-Photochemical Quenching and Photosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Lewandowska, M.; Witoń, D.; Fichman, Y.; Mittler, R.; Karpiński, S.M. Aboveground Plant-to-Plant Electrical Signaling Mediates Network Acquired Acclimation. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 3047–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecka, M.; Lewandowska, M.; Dąbrowska-Bronk, J.; Białasek, M.; Barczak-Brzyżek, A.; Kulasek, M.; Mielecki, J.; Kozłowska-Makulska, A.; Gawroński, P.; Karpiński, S. Photosystem II 22kDa Protein Level-a Prerequisite for Excess Light-Inducible Memory, Cross-Tolerance to UV-C and Regulation of Electrical Signalling. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, A.; Mühlenbock, P.; Rustérucci, C.; Chang, C.C.-C.; Miszalski, Z.; Karpinska, B.; Parker, J.E.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Karpinski, S. LESION SIMULATING DISEASE 1 Is Required for Acclimation to Conditions That Promote Excess Excitation Energy. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2818–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlenbock, P.; Szechynska-Hebda, M.; Płaszczyca, M.; Baudo, M.; Mateo, A.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Parker, J.E.; Karpinska, B.; Karpiński, S. Chloroplast Signaling and LESION SIMULATING DISEASE1 Regulate Crosstalk Between Light Acclimation and Immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2339–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Lewandowska, M.; Karpiński, S. Electrical Signaling, Photosynthesis and Systemic Acquired Acclimation. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdiak, P.; Rusaczonek, A.; Witoń, D.; Głów, D.; Karpiński, S. Cysteine-Rich Receptor-like Kinase CRK5 as a Regulator of Growth, Development, and Ultraviolet Radiation Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3325–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawroński, P.; Burdiak, P.; Scharff, L.B.; Mielecki, J.; Górecka, M.; Zaborowska, M.; Leister, D.; Waszczak, C.; Karpiński, S. CIA2 and CIA2-LIKE Are Required for Optimal Photosynthesis and Stress Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2021, 105, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-W.; Huang, Y.-C.; Chang, H.-Y. CIA2 Coordinately Up-Regulates Protein Import and Synthesis in Leaf Chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 2009, 150, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bita, C.E.; Gerats, T. Plant Tolerance to High Temperature in a Changing Environment: Scientific Fundamentals and Production of Heat Stress-Tolerant Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh, A.; Sevanto, S.; Close, J.D.; Nicotra, A.B. The Influence of Leaf Size and Shape on Leaf Thermal Dynamics: Does Theory Hold up Under Natural Conditions? Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S. Leaves in the Lowest and Highest Winds: Temperature, Force and Shape. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecco, P.A.; Urcelay, C.; Díaz, S.; Cabido, M.; Pérez-Harguindeguy, N. Contrasting Functional Trait Syndromes Underlay Woody Alien Success in the Same Ecosystem. Austral Ecol. 2013, 38, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingchao, W.; Yong, L.; Biyan, Z.; Zhiqun, H. Effects of Cytokinin and Abscisic Acid on Heat Resistance of Vetiveria zizanioides. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2022, 50, 12755. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Yadav, P.; Khanna, K. Photosynthetic Response of Plants under Different Abiotic Stresses: A Review. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qi, L.; Li, Y.; Chu, J.; Li, C. PIF4–Mediated Activation of YUCCA8 Expression Integrates Temperature into the Auxin Pathway in Regulating Arabidopsis Hypocotyl Growth. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, T.M.; Vukašinović, N.; Liu, D.; Russinova, E.; Yin, Y. Brassinosteroids: Multidimensional Regulators of Plant Growth, Development, and Stress Responses. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, A.; Lachowiec, J. Roles of Brassinosteroids in Mitigating Heat Stress Damage in Cereal Crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poór, P.; Nawaz, K.; Gupta, R.; Ashfaque, F.; Khan, M.I.R. Ethylene Involvement in the Regulation of Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Shen, Y.; Kon, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, M.; Wu, X. Protein–Protein Interactions of the Baculovirus per Os Infectivity Factors (PIFs) in the PIF Complex. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.M.; Cristescu, S.M.; Miersch, O.; Harren, F.J.; Wasternack, C.; Mur, L.A. Jasmonates Act with Salicylic Acid to Confer Basal Thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.R.; Asgher, M.; Khan, N.A. Alleviation of Salt-Induced Photosynthesis and Growth Inhibition by Salicylic Acid Involves Glycinebetaine and Ethylene in Mungbean (Vigna radiata L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Tada, Y. Regulation of Water, Salinity, and Cold Stress Responses by Salicylic Acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Finka, A.; Goloubinoff, P. How Do Plants Feel the Heat? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012, 37, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N. Hormone Signaling Pathways under Stress Combinations. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1247139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Adams, W.W. Xanthophyll Cycle and Light Stress in Nature: Uniform Response to Excess Direct Sunlight among Higher Plant Species. Planta 1996, 198, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyogi, K.K.; Shih, C.; Soon Chow, W.; Pogson, B.J.; DellaPenna, D.; Björkman, O. Photoprotection in a Zeaxanthin- and Lutein-Deficient Double Mutant of Arabidopsis. Photosynth. Res. 2001, 67, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.D.; Zeevaart, J.A. The Aba Mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana Is Impaired in Epoxy-Carotenoid Biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 7496–7499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaux, M.; Niyogi, K.K. The Violaxanthin Cycle Protects Plants from Photooxidative Damage by More than One Mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 8762–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, G.C.; Govindjee. The Non-Photochemical Quenching of the Electronically Excited State of Chlorophyll a in Plants: Definitions, Timelines, Viewpoints, Open Questions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, K.; Kudla, J. Calcium Decoding Mechanisms in Plants. Biochimie 2011, 93, 2054–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Pan, R.; Shabala, L.; Shabala, S.; Zhang, W.-Y. Temperature Influences Waterlogging Stress-Induced Damage in Arabidopsis Through the Regulation of Photosynthesis and Hypoxia-Related Genes. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 89, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chu, C.; Yao, S. The Impact of High-Temperature Stress on Rice: Challenges and Solutions. Crop J. 2021, 9, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WU, H.; LUO, D.; Vignols, F.; JINN, T. Heat Shock-Induced Biphasic Ca2+ Signature and OsCaM1-1 Nuclear Localization Mediate Downstream Signalling in Acquisition of Thermotolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M. Plant Drought Stress: Effects, Mechanisms and Management. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 153–188. [Google Scholar]

- Surabhi, G.K.; Seth, J.K. Exploring In-built Defense Mechanisms in Plants under Heat Stress. In Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants: Physiological, Molecular and Genetic Perspectives; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 239–282. [Google Scholar]

- Larkindale, J.; Knight, M.R. Protection against Heat Stress-Induced Oxidative Damage in Arabidopsis Involves Calcium, Abscisic Acid, Ethylene, and Salicylic Acid. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidi, Y.; Finka, A.; Muriset, M.; Bromberg, Z.; Weiss, Y.G.; Maathuis, F.J.; Goloubinoff, P. The Heat Shock Response in Moss Plants Is Regulated by Specific Calcium-Permeable Channels in the Plasma Membrane. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2829–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kregel, K.C. Invited Review: Heat Shock Proteins: Modifying Factors in Physiological Stress Responses and Acquired Thermotolerance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 92, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I.; Glatz, A.; Nakamoto, H.; Mishkind, M.L.; Munnik, T.; Saidi, Y.; Goloubinoff, P.; Harwood, J.L.; Vigh, L. Heat Shock Response in Photosynthetic Organisms: Membrane and Lipid Connections. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012, 51, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, K.E.; Tunc-Ozdemir, M.; Harper, J.F. Temperature Stress and Plant Sexual Reproduction: Uncovering the Weakest Links. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1959–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourani, M.; Mohareb, F.; Rezwan, F.I.; Anastasiadi, M.; Hammond, J.P. Genetic and Physiological Responses to Heat Stress in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 832147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciolla, C.; Paradiso, A.; de Pinto, M.C. Cellular Redox Homeostasis as Central Modulator in Plant Stress Response. In Redox State as a Central Regulator of Plant-Cell Stress Responses; Gupta, D.K., Palma, J.M., Corpas, F.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-3-319-44081-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Luan, Y.; Meng, J.; Sun, J.; Tao, J.; Zhao, D. WRKY Transcription Factor Response to High-Temperature Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Machinery in Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-L.; Chen, J.-H.; He, N.-Y.; Guo, F.-Q. Metabolic Reprogramming in Chloroplasts under Heat Stress in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Wang, A.; Sun, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhang, L. Identification and Expression of NAC Transcription Factors of Vaccinium corymbosum L. in Response to Drought Stress. Forests 2019, 10, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Raza, A.; Iqbal, J.; Shaukat, M.; Mahmood, T. Analyzing the Regulatory Role of Heat Shock Transcription Factors in Plant Heat Stress Tolerance: A Brief Appraisal. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 5771–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Still, C.J.; Rastogi, B.; Page, G.F.M.; Griffith, D.M.; Sibley, A.; Schulze, M.; Hawkins, L.; Pau, S.; Detto, M.; Helliker, B.R. Imaging Canopy Temperature: Shedding (Thermal) Light on Ecosystem Processes. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Li, Y.-J.; Chen, S.-Z. Abscisic Acid-Induced Thermotolerance in Maize Seedlings Is Mediated by Calcium and Associated with Antioxidant Systems. J. Plant Physiol. 1998, 153, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Sairam, R.K.; Srivastava, G.C.; Tyagi, A.; Meena, R.C. Role of ABA, Salicylic Acid, Calcium and Hydrogen Peroxide on Antioxidant Enzymes Induction in Wheat Seedlings. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaul, I.M.; Baohua, F.; Tingting, C.; Weimeng, F.; Caixia, Z.; Longxing, T.; Guanfu, F. Abscisic Acid Prevents Pollen Abortion under High-Temperature Stress by Mediating Sugar Metabolism in Rice Spikelets. Physiol. Plant. 2019, 165, 644–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, K.A.; Lee, S.H.; Patel, D.; Kumar, S.V.; Spartz, A.K.; Gu, C.; Ye, S.; Yu, P.; Breen, G.; Cohen, J.D. Phytochrome-Interacting Factor 4 (PIF4) Regulates Auxin Biosynthesis at High Temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20231–20235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Dalal, M.; Verma, R.K.; Kumar, S.V.; Yadav, S.K.; Pushkar, S.; Kushwaha, S.R.; Bhowmik, A.; Chinnusamy, V. Auxin Protects Spikelet Fertility and Grain Yield under Drought and Heat Stresses in Rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 150, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Bhardwaj, M.; Mehrotra, S.; Chowdhary, A.A.; Srivastava, V. The Contribution of Phytohormones in Plant Thermotolerance. In Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 213–238. ISBN 978-1-119-43240-1. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Cui, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z. Exogenous Cytokinins Increase Grain Yield of Winter Wheat Cultivars by Improving Stay-Green Characteristics under Heat Stress. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Choukimath, A.; Isenegger, D.; Panozzo, J.; Spangenberg, G.; Kant, S. Improved Wheat Growth and Yield by Delayed Leaf Senescence Using Developmentally Regulated Expression of a Cytokinin Biosynthesis Gene. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazorra, L.M.; Holton, N.; Bishop, G.J.; Núñez, M. Heat Shock Response in Tomato Brassinosteroid Mutants Indicates That Thermotolerance Is Independent of Brassinosteroid Homeostasis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thussagunpanit, J.; Jutamanee, K.; Sonjaroon, W.; Kaveeta, L.; Chai-Arree, W.; Pankean, P.; Suksamrarn, A. Effects of Brassinosteroid and Brassinosteroid Mimic on Photosynthetic Efficiency and Rice Yield under Heat Stress. Photosynthetica 2015, 53, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Islam, M.R.; Liu, Y.; Luo, H.; Yang, P.; Wang, Q.; Chan, Z. Transcriptomic Profiling of Tall Fescue in Response to Heat Stress and Improved Thermotolerance by Melatonin and 24-Epibrassinolide. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Nazar, R.; Khan, M.I.R.; Masood, A.; Khan, N.A. Role of Gibberellins in Regulation of Source? Sink Relations under Optimal and Limiting Environmental Conditions. Curr. Sci. 2011, 100, 998–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Cui, K.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Fahad, S.; Hu, Q.; Huang, J.; Nie, L.; Peng, S. Heat-Induced Phytohormone Changes Are Associated with Disrupted Early Reproductive Development and Reduced Yield in Rice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Zhang, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Tao, L.; Fu, G. Salicylic Acid Reverses Pollen Abortion of Rice Caused by Heat Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.H.; Kumar, V. Heat Stress Tolerance in Plants: Physiological, Molecular and Genetic Perspectives; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 1-119-43236-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Seomun, S.; Yoon, Y.; Jang, G. Jasmonic Acid in Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Interaction with Abscisic Acid. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, Y.; Maruyama, K.; Qin, F.; Osakabe, Y.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Dual Function of an Arabidopsis Transcription Factor DREB2A in Water-Stress-Responsive and Heat-Stress-Responsive Gene Expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18822–18827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, N.; Sejima, H.; Tam, R.; Schlauch, K.; Mittler, R. Identification of the MBF1 Heat-Response Regulon of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2011, 66, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Kirkham, M. Drought-Stress-Induced Changes in Activities of Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase, and Peroxidase in Wheat Species. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994, 35, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S. Friend or Foe? Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Scavenging and Signaling in Plant Response to Environmental Stresses. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 122, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Regulator | Molecular/Structural Type | Primary Function Under Heat Stress | Mechanistic Basis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive structural traits | Leaf size, shape, orientation; cuticle, trichomes | Morphological traits | Heat avoidance; ↓ foliar temperature | Reduced radiation absorption, thinner boundary layer, enhanced convective and radiative heat loss | [47,91,92] |

| Canopy architecture, self-shading | Whole-plant traits | Buffer thermal extremes | Reduced solar interception; canopy-scale thermal heterogeneity | [34,129] | |

| Phytohormone | Abscisic acid (ABA) | Sesquiterpene hormone | ↑ Thermotolerance ↓ transpiration | Ca2+ influx, antioxidant enzyme induction (SOD, CAT, APX), membrane stabilization; stomatal closure | [130,131,132] |

| Auxins (IAA, NAA) | Indole hormones | Developmental heat adaptation | Maintains pollen viability, cell division, antioxidant balance | [133,134,135] | |

| Cytokinins (CKs) | Adenine derivatives | Yield stability under heat | Delay senescence, maintain grain filling and sink–source relations | [3,136,137] | |

| Brassinosteroids (BRs) | Steroid hormones | ↑ Thermotolerance | Enhance photosynthesis, ROS detoxification, translational stability | [138,139,140] | |

| Gibberellins (GAs) | Diterpenoid hormones | Developmental plasticity | GA–PIF4–auxin integration; flowering and thermomorphogenesis | [135,141,142] | |

| Ethylene | Gaseous hormone | Context-dependent | Modulates oxidative stress and senescence; EIN2 may negatively regulate thermotolerance | [102,117,135] | |

| Salicylic acid (SA) | Phenolic hormone | Basal and acquired thermotolerance | Enhances antioxidant capacity, proline accumulation, pollen protection | [102,143,144] | |

| Jasmonic acid (JA) | Lipid hormone | Basal thermotolerance | Activates stress-responsive transcriptional networks | [101,145] | |

| Transcription factor | HSFA1 (A/B/D/E) | HSF family | Master regulator of HSR | Activates HSP genes and stress-related enzymes | [117,118] |

| HSFA2 | HSF family | Acquired thermotolerance | Sustains HSP expression during prolonged or repeated stress | [113] | |

| HSFBs | HSF family | HSR fine-tuning | Modulate intensity and duration of heat response | [128] | |

| DREB2A | AP2/ERF family | Heat and drought response | Activates abiotic stress-responsive genes | [113,146] | |

| MBF1c | Transcriptional co-activator | ROS-linked thermotolerance | Bridges oxidative signaling and HSR | [147] | |

| NAC TFs (e.g., NAC019, ONAC066) | NAC family | Heat and oxidative stress tolerance | Direct activation of HSFs and stress-responsive genes | [127,128] | |

| WRKY TFs | WRKY family | Heat–ROS signaling | MAPK-mediated regulation of stress genes | [124] | |

| PIF4 | bHLH family | Thermomorphogenesis | Integrates GA, auxin, and temperature signaling | [133,135] | |

| Signaling system | Ca2+–Calmodulin (CaM3) | Ca2+ sensor | Heat signal transduction | Activates HSFs via CBK3 and PP7 | [111,113] |

| ROS signaling | Redox system | Stress perception and signaling | H2O2 activates HSR and antioxidant genes | [125] | |

| Protective system | Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) | Molecular chaperones | Protein protection | Prevent denaturation and aggregation | [119,121] |

| Antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, APX) | Enzymatic defense | ROS detoxification | Prevent lipid peroxidation and membrane damage | [148,149] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zarrin Ghalami, R.; Duszyn, M.; Karpiński, S. Absorption of Energy in Excess, Photoinhibition, Transpiration, and Foliar Heat Emission Feedback Loops During Global Warming. Cells 2026, 15, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010075

Zarrin Ghalami R, Duszyn M, Karpiński S. Absorption of Energy in Excess, Photoinhibition, Transpiration, and Foliar Heat Emission Feedback Loops During Global Warming. Cells. 2026; 15(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleZarrin Ghalami, Roshanak, Maria Duszyn, and Stanisław Karpiński. 2026. "Absorption of Energy in Excess, Photoinhibition, Transpiration, and Foliar Heat Emission Feedback Loops During Global Warming" Cells 15, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010075

APA StyleZarrin Ghalami, R., Duszyn, M., & Karpiński, S. (2026). Absorption of Energy in Excess, Photoinhibition, Transpiration, and Foliar Heat Emission Feedback Loops During Global Warming. Cells, 15(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010075