Acute Cold Exposure Cell-Autonomously Reduces mTORC1 Signaling and Protein Synthesis Independent of AMPK

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Measurement of Protein Synthesis and Cell Signaling

2.3. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.4. Myotube Differentiation Assay

2.5. Western Blotting

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

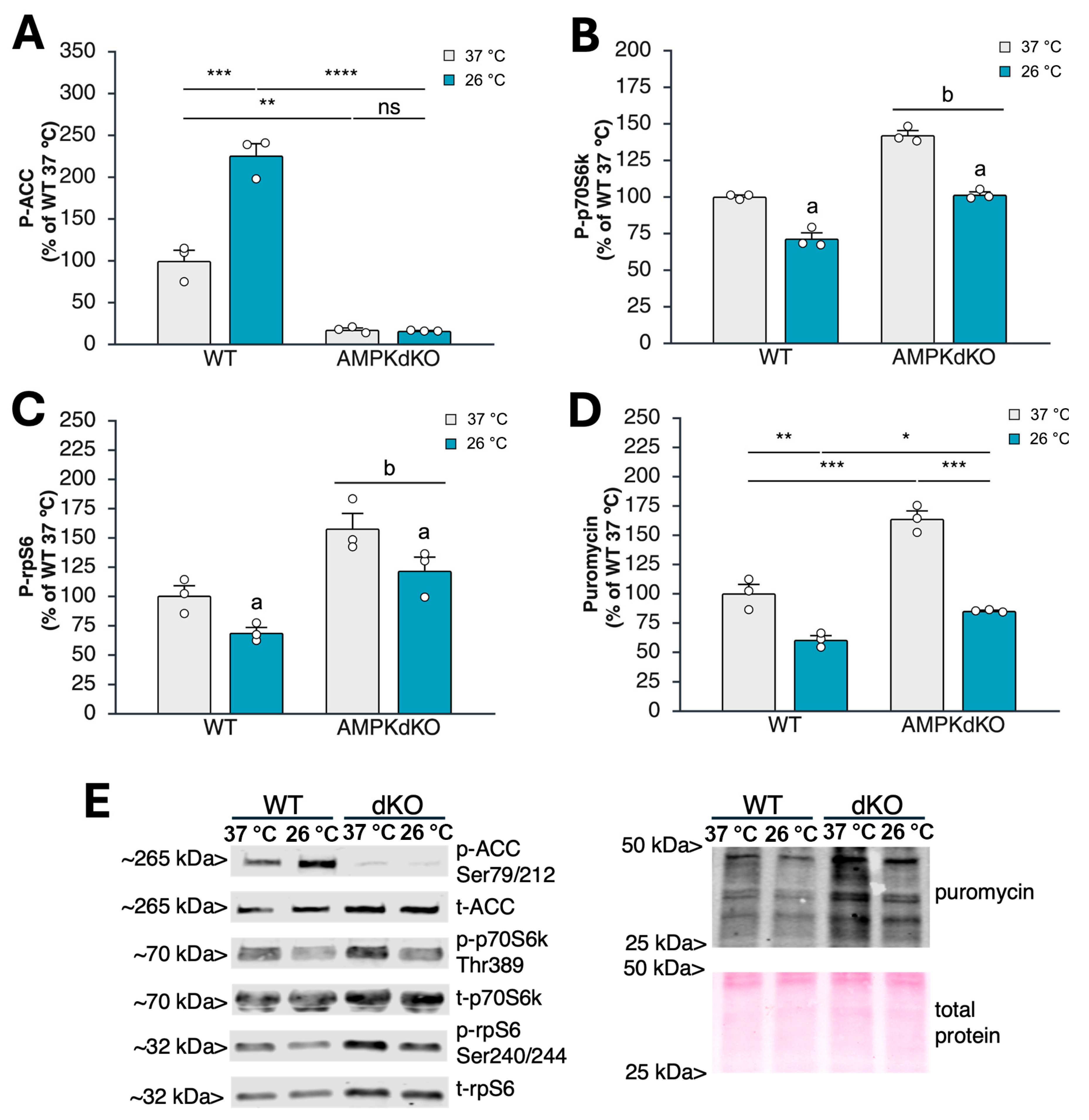

3.1. Acute Cold Exposure Limits Myoblast Protein Synthesis and mTORC1 Signaling in an AMPK-Independent Manner

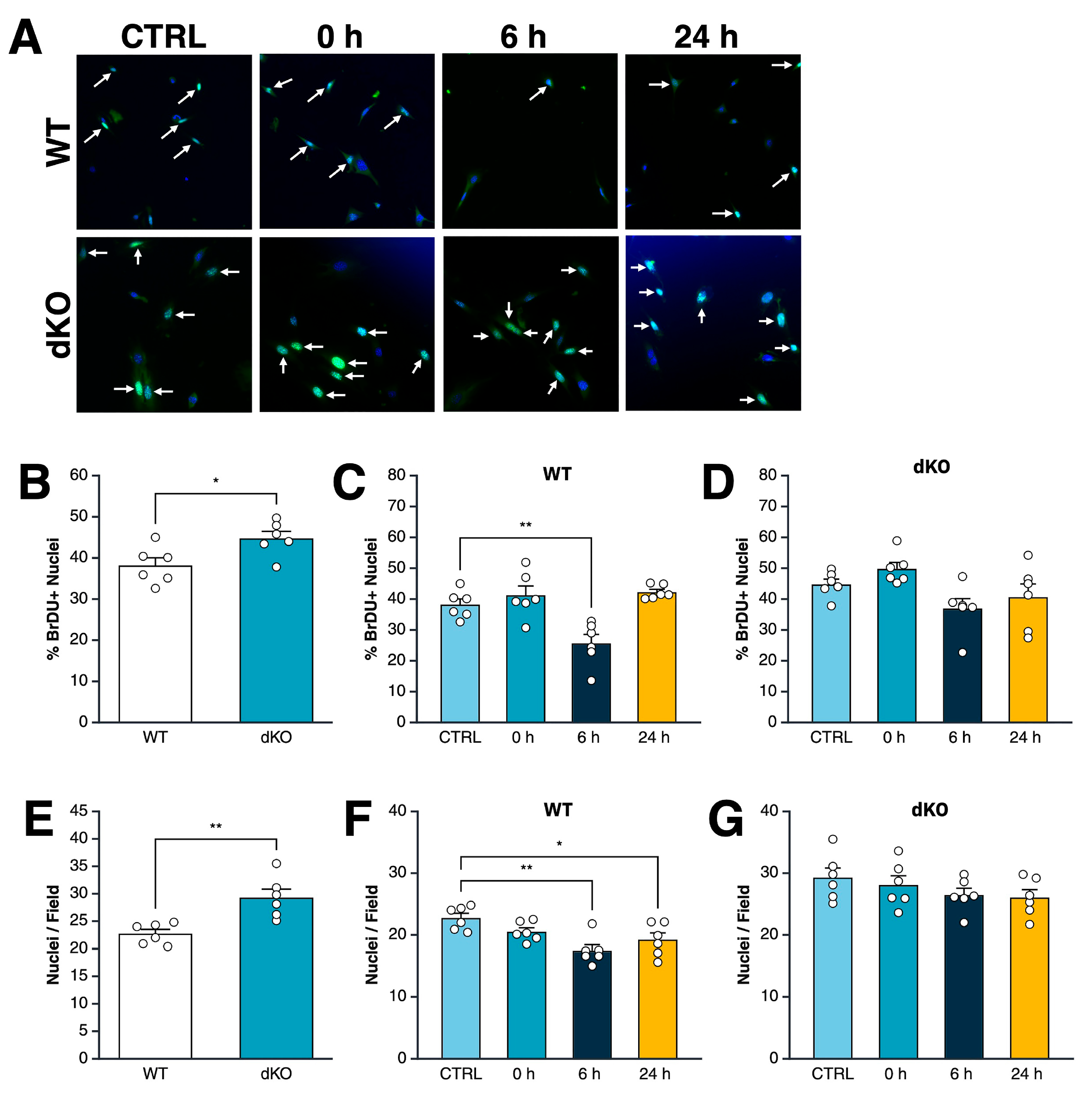

3.2. Acute Exposure to Cold Drives an AMPK-Dependent Decrease in Myoblast Proliferation Rate

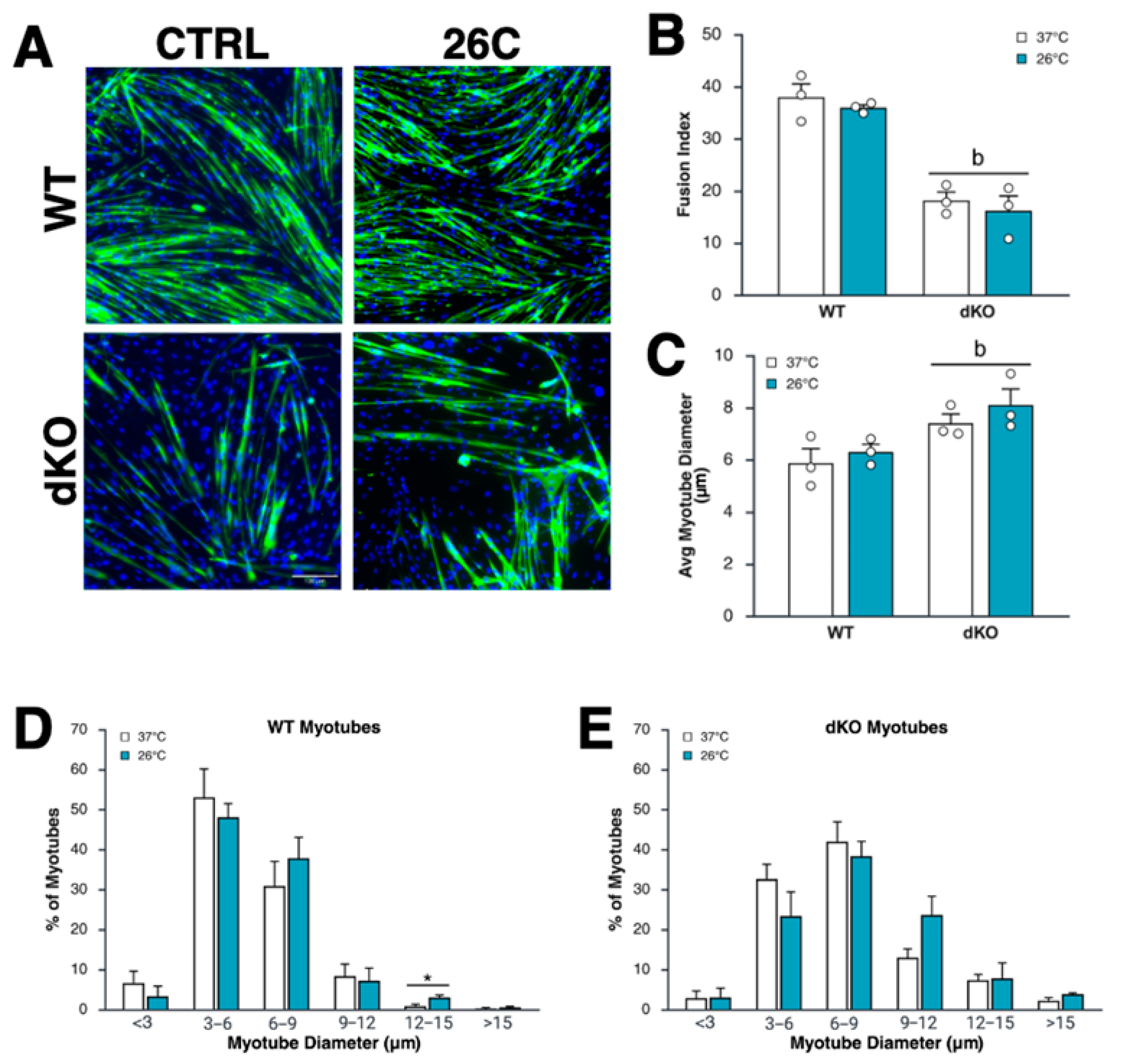

3.3. Myoblast Differentiation Is Suppressed by the Lack of AMPK, but Is Unaffected by Intermittent Moderate Cold Exposure

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| dKO | AMPK alpha double knockout |

| mTORC1 | mechansistic target of rapamycin, complex 1 |

| p70S6k | ribosomal protein S6 kinase, of 70 kDa |

| rpS6 | ribosomal protein S6 |

| TRP | transient receptor potential |

| TRPM8 | TRP subfamily M, member 8 |

| WT | wild-type |

References

- Kunkle, B.F.; Kothandaraman, V.; Goodloe, J.B.; Curry, E.J.; Friedman, R.J.; Li, X.; Eichinger, J.K. Orthopaedic Application of Cryotherapy: A Comprehensive Review of the History, Basic Science, Methods, and Clinical Effectiveness. JBJS Rev. 2021, 9, e20.00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.E.; Wells, G.D. Cold-water immersion and other forms of cryotherapy: Physiological changes potentially affecting recovery from high-intensity exercise. Extrem. Physiol. Med. 2013, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racinais, S.; Dablainville, V.; Rousse, Y.; Ihsan, M.; Grant, M.E.; Schobersberger, W.; Budgett, R.; Engebretsen, L. Cryotherapy for treating soft tissue injuries in sport medicine: A critical review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frohlich, M.; Faude, O.; Klein, M.; Pieter, A.; Emrich, E.; Meyer, T. Strength training adaptations after cold-water immersion. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 2628–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.A.; Raastad, T.; Markworth, J.F.; Figueiredo, V.C.; Egner, I.M.; Shield, A.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Coombes, J.S.; Peake, J.M. Post-exercise cold water immersion attenuates acute anabolic signalling and long-term adaptations in muscle to strength training. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 4285–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand-Gravier, T.; Solsona, R.; Dablainville, V.; Racinais, S.; Borrani, F.; Bernardi, H.; Sanchez, A.M.J. Effects of thermal interventions on skeletal muscle adaptations and regeneration: Perspectives on epigenetics: A narrative review. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2025, 125, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltenrich, N. Between Extremes: Health Effects of Heat and Cold. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, A275–A280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straat, M.E.; Jurado-Fasoli, L.; Ying, Z.; Nahon, K.J.; Janssen, L.G.M.; Boon, M.R.; Grabner, G.F.; Kooijman, S.; Zimmermann, R.; Giera, M.; et al. Cold exposure induces dynamic changes in circulating triacylglycerol species, which is dependent on intracellular lipolysis: A randomized cross-over trial. eBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haman, F.; Peronnet, F.; Kenny, G.P.; Massicotte, D.; Lavoie, C.; Scott, C.; Weber, J.M. Effect of cold exposure on fuel utilization in humans: Plasma glucose, muscle glycogen, and lipids. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, L.H.; Zanon, N.M.; Garofalo, M.A.; Navegantes, L.C.; Kettelhut, I.C. Effect of short-term cold exposure on skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 115, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Park, J.; Lim, K. The effects of exercise and cold exposure on mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. J. Exerc. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 21, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Ricard, Y.; Cormier, P.; Morales, J.; Boutet, A. mTOR Signaling at the Crossroad between Metazoan Regeneration and Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Strasburg, G.M.; Reed, K.M.; Velleman, S.G. Thermal stress affects proliferation and differentiation of turkey satellite cells through the mTOR/S6K pathway in a growth-dependent manner. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, J.J.; Broatch, J.R.; Trewin, A.J.; Hanson, E.D.; Argus, C.K.; Garnham, A.P.; Halson, S.L.; Polman, R.C.; Bishop, D.J.; Petersen, A.C. Cold water immersion attenuates anabolic signaling and skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy, but not strength gain, following whole-body resistance training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 127, 1403–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlynn, M.L.; Rosales, A.M.; Collins, C.W.; Slivka, D.R. The isolated effects of local cold application on proteolytic and myogenic signaling. Cryobiology 2023, 112, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, W.W.; Thomson, D.M. Cellular energy sensing and signaling by AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2007, 47, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolster, D.R.; Crozier, S.J.; Kimball, S.R.; Jefferson, L.S. AMP-activated protein kinase suppresses protein synthesis in rat skeletal muscle through down-regulated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 23977–23980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinn, D.M.; Shackelford, D.B.; Egan, D.F.; Mihaylova, M.M.; Mery, A.; Vasquez, D.S.; Turk, B.E.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, K.; Zhu, T.; Guan, K.L. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 2003, 115, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, D.M.; Fick, C.A.; Gordon, S.E. AMPK activation attenuates S6K1, 4E-BP1, and eEF2 signaling responses to high-frequency electrically stimulated skeletal muscle contractions. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepa-Kishi, D.M.; Sotoudeh-Nia, Y.; Iqbal, A.; Bikopoulos, G.; Ceddia, R.B. Cold acclimation causes fiber type-specific responses in glucose and fat metabolism in rat skeletal muscles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedert, C.J.; Bagdady, K.R.; Fisher, J.S. Prior Treatment with AICAR Causes the Selective Phosphorylation of mTOR Substrates in C2C12 Cells. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 8040–8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantier, L.; Mounier, R.; Leclerc, J.; Pende, M.; Foretz, M.; Viollet, B. Coordinated maintenance of muscle cell size control by AMP-activated protein kinase. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 3555–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecien, S.Y.; Mathew, S.; Howatson, G.; McHugh, M.P. The effect of varying degrees of compression from elastic vs plastic wrap on quadriceps intramuscular temperature during wetted ice application. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, C.A.; Mabrey, D.M.; Frey, J.W.; Miu, M.H.; Schmidt, E.K.; Pierre, P.; Hornberger, T.A. Novel insights into the regulation of skeletal muscle protein synthesis as revealed by a new nonradioactive in vivo technique. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardie, D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase—A journey from 1 to 100 downstream targets. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 2327–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.J.; Kouw, I.W.K.; Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Smeets, J.S.J.; Senden, J.M.; Lichtenbelt, W.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Postexercise cooling impairs muscle protein synthesis rates in recreational athletes. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 755–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, R.; Chaillou, T. Mild hypothermia affects the morphology and impairs glutamine-induced anabolic response in human primary myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 317, C101–C110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanba, D.; Sakabe, J.I.; Mosig, J.; Brouard, M.; Toki, F.; Shimokawa, M.; Kamiya, M.; Braschler, T.; Azzabi, F.; Droz-Georget Lathion, S.; et al. Low temperature and mTOR inhibition favor stem cell maintenance in human keratinocyte cultures. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e55439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skagen, C.; Lovsletten, N.G.; Asoawe, L.; Al-Karbawi, Z.; Rustan, A.C.; Thoresen, G.H.; Haugen, F. Functional expression of the thermally activated transient receptor potential channels TRPA1 and TRPM8 in human myotubes. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 116, 103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Coughlan, K.A.; Ding, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Song, P.; Zou, M.H. AMPKalpha1 deficiency promotes cellular proliferation and DNA damage via p21 reduction in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, E.; Abbadessa, G.; Giordano, M.; Grasso, L.; Borrione, P.; Racca, S. Metformin regulates myoblast differentiation through an AMPK-dependent mechanism. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, S.; Asgar, N.F.; Yokota, S.; Saito, K.; Minokoshi, Y. Role of the alpha2 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase and its nuclear localization in mitochondria and energy metabolism-related gene expressions in C2C12 cells. Metabolism 2019, 90, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, S.; Foretz, M.; Viollet, B.; Du, M. Obesity Impairs Skeletal Muscle Regeneration Through Inhibition of AMPK. Diabetes 2016, 65, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, P.; Rajalaxmi, S.; Saha, P.; Thakur, P.S.; Hashmi, M.A.; Lal, H.; Saini, N.; Singh, N.; Ramanathan, A. Cold-shock proteome of myoblasts reveals role of RBM3 in promotion of mitochondrial metabolism and myoblast differentiation. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.G.; Seebacher, F. Thermal conditions experienced during differentiation affect metabolic and contractile phenotypes of mouse myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 311, R457–R465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Zhao, J.X.; Liang, J.; Zhu, M.J.; Foretz, M.; Viollet, B.; Du, M. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates myogenin expression and myogenesis via histone deacetylase 5. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 305, C887–C895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sung, B.Y.; Ford, E.J.; Foster, D.J.; Fullmer, K.J.; Cromwell, C.; Viollet, B.; Thomson, D.M. Acute Cold Exposure Cell-Autonomously Reduces mTORC1 Signaling and Protein Synthesis Independent of AMPK. Cells 2026, 15, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010065

Sung BY, Ford EJ, Foster DJ, Fullmer KJ, Cromwell C, Viollet B, Thomson DM. Acute Cold Exposure Cell-Autonomously Reduces mTORC1 Signaling and Protein Synthesis Independent of AMPK. Cells. 2026; 15(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Benjamin Y., Eliza J. Ford, Daniel J. Foster, Kyler J. Fullmer, Cosette Cromwell, Benoit Viollet, and David M. Thomson. 2026. "Acute Cold Exposure Cell-Autonomously Reduces mTORC1 Signaling and Protein Synthesis Independent of AMPK" Cells 15, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010065

APA StyleSung, B. Y., Ford, E. J., Foster, D. J., Fullmer, K. J., Cromwell, C., Viollet, B., & Thomson, D. M. (2026). Acute Cold Exposure Cell-Autonomously Reduces mTORC1 Signaling and Protein Synthesis Independent of AMPK. Cells, 15(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010065