Phosphoproteomic Profiling Reveals Overlapping and Distinct Signaling Pathways in Dictyostelium discoideum in Response to Two Different Chemorepellents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Strains and Culture

2.2. Stimulation with AprA and polyP

2.3. Proteomic and Phosphoproteomic Sample Preparation and Analysis

2.4. Data Normalization and Analysis

2.5. Protein Annotation Using AlphaFold and Foldseek

2.6. Functional Validation Assays

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

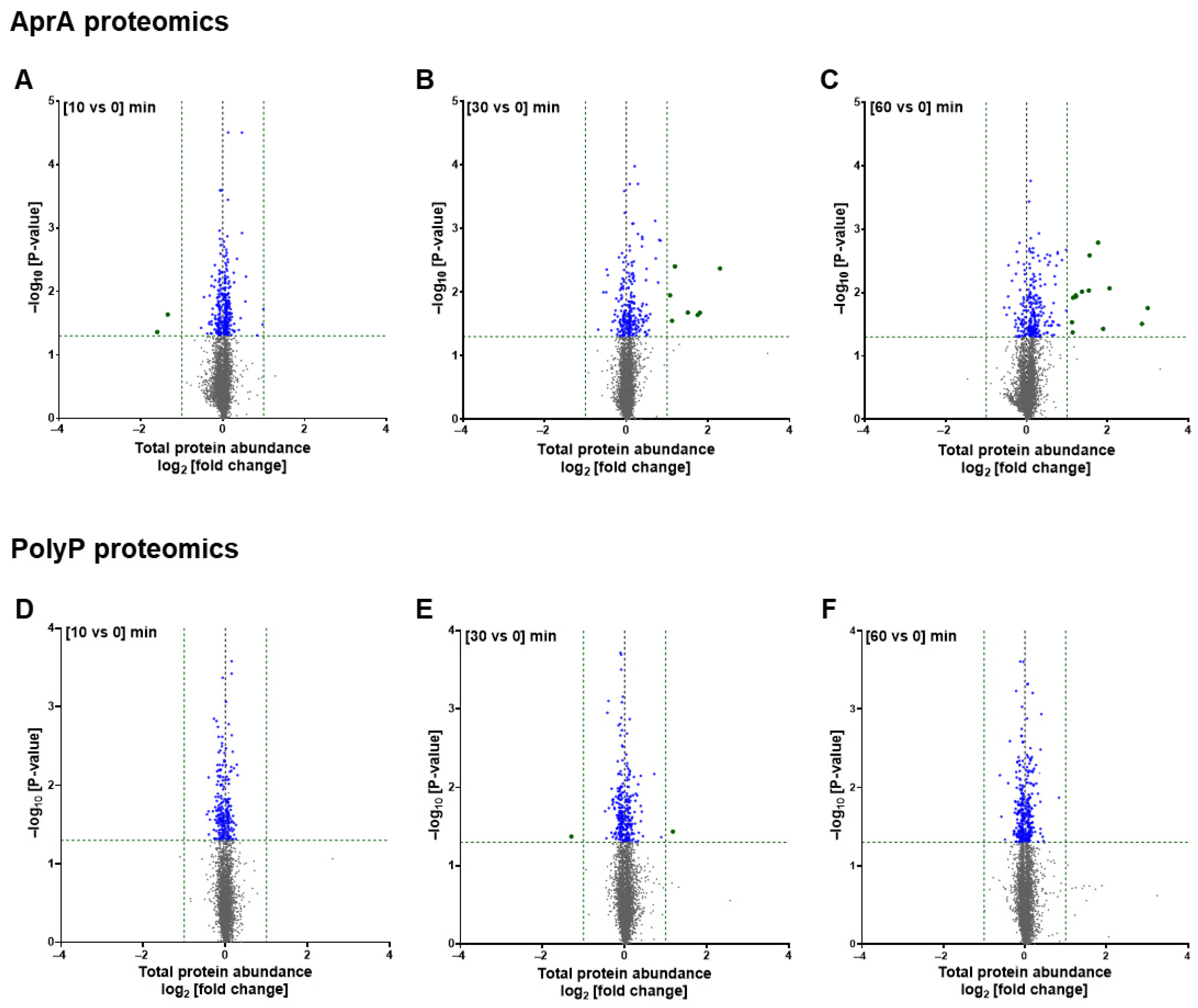

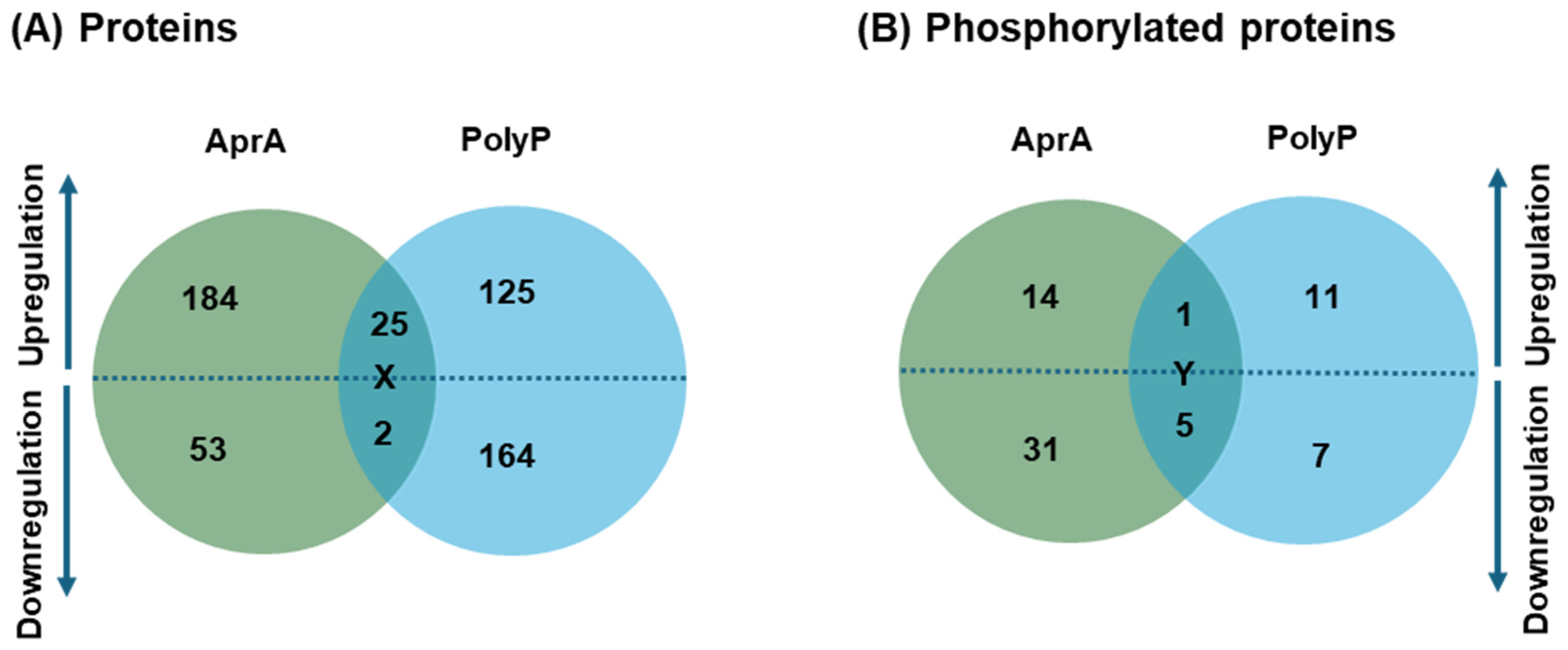

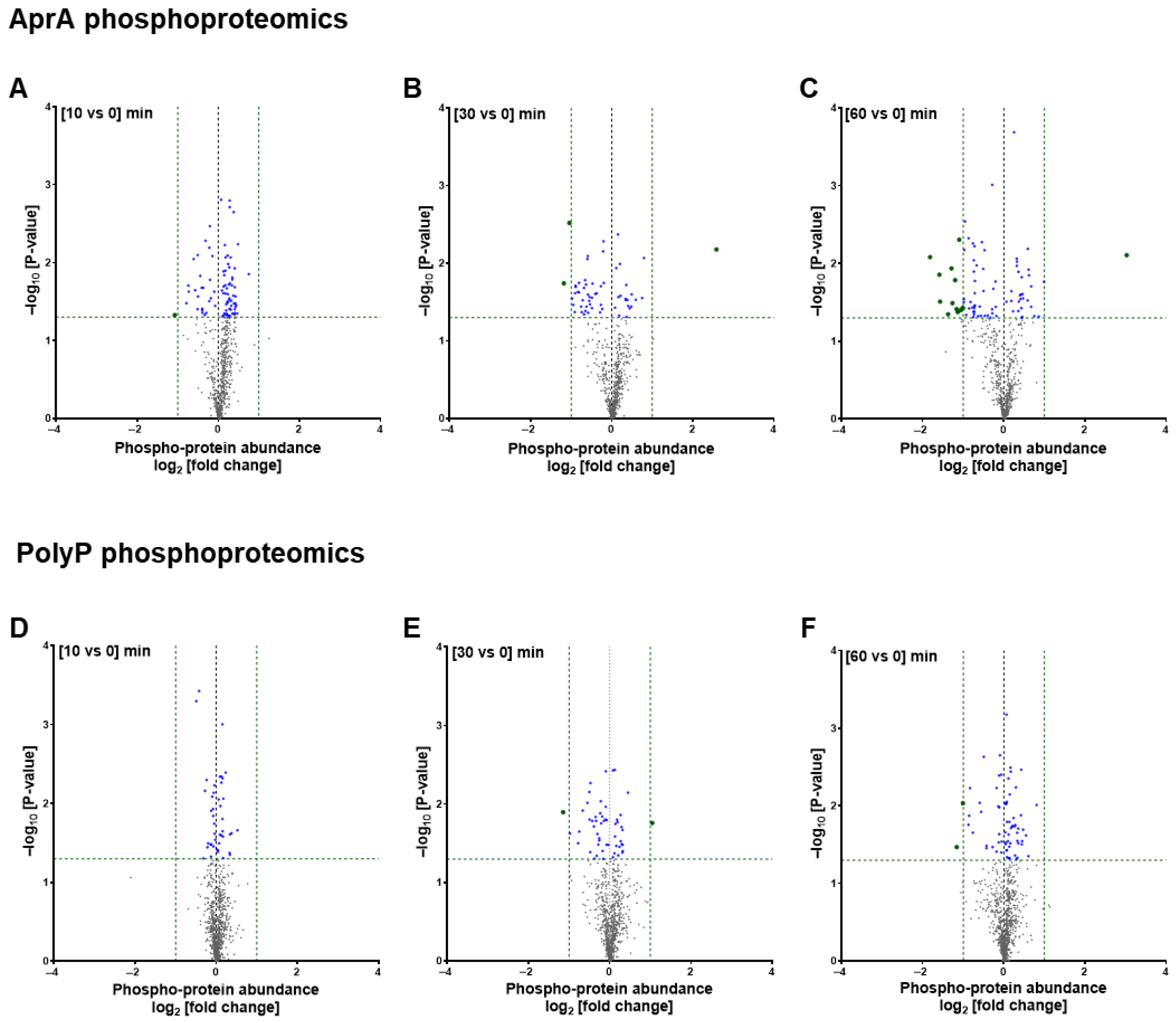

3.1. AprA and polyP Have Mostly Different Effects on Protein Levels and Phosphorylation

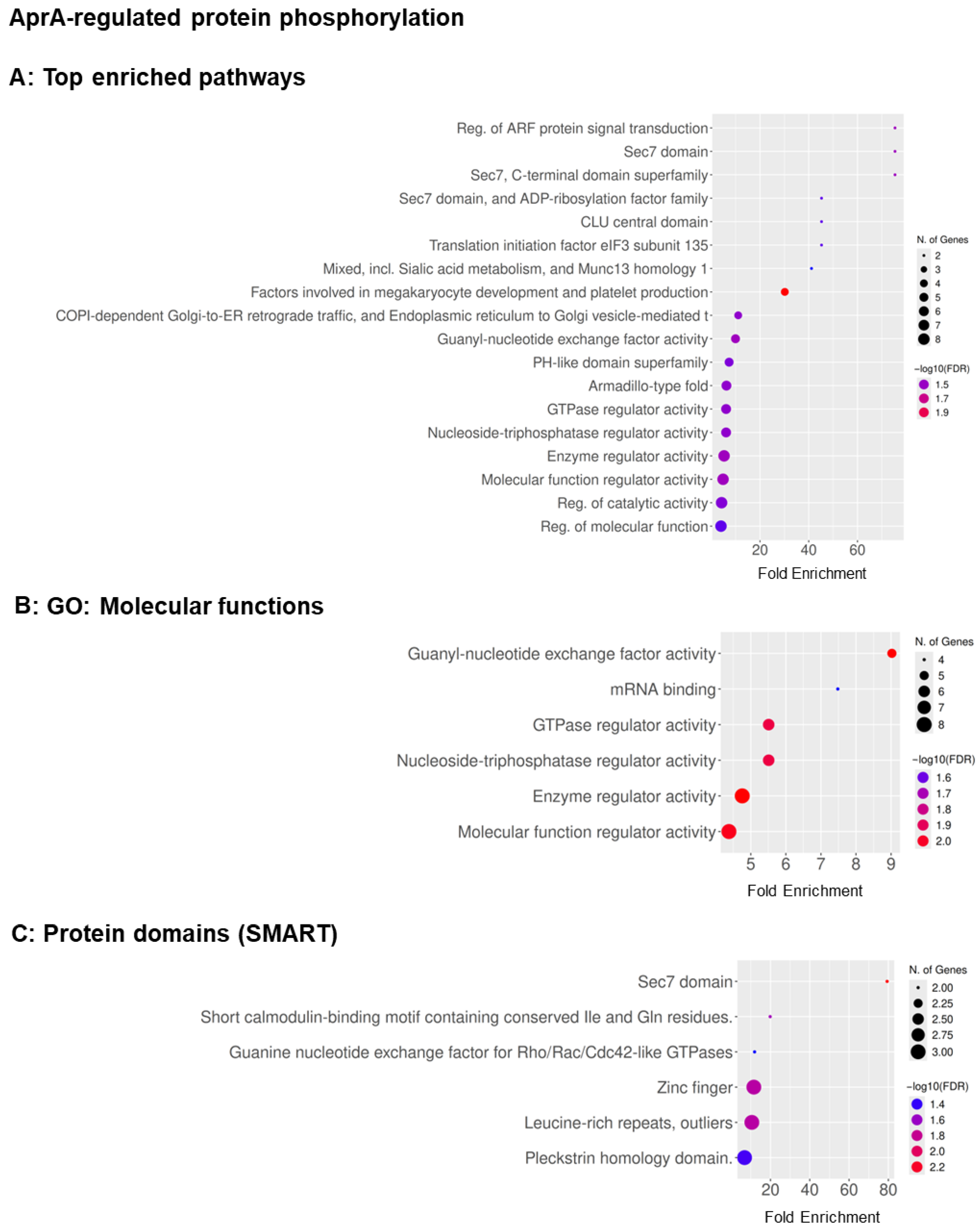

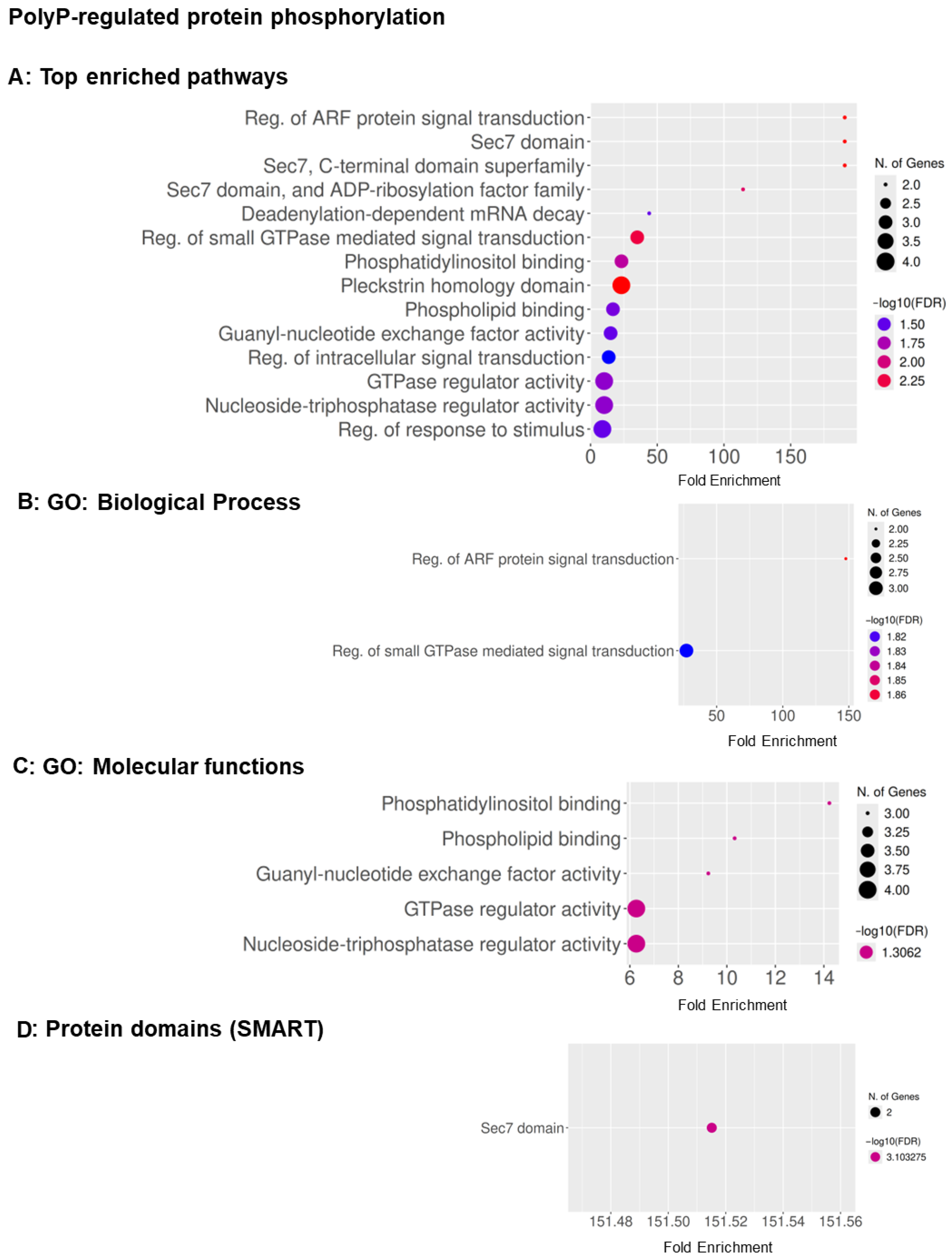

3.2. GO Term Analysis Reveals Overlapping and Distinct Pathways Regulated by AprA and polyP

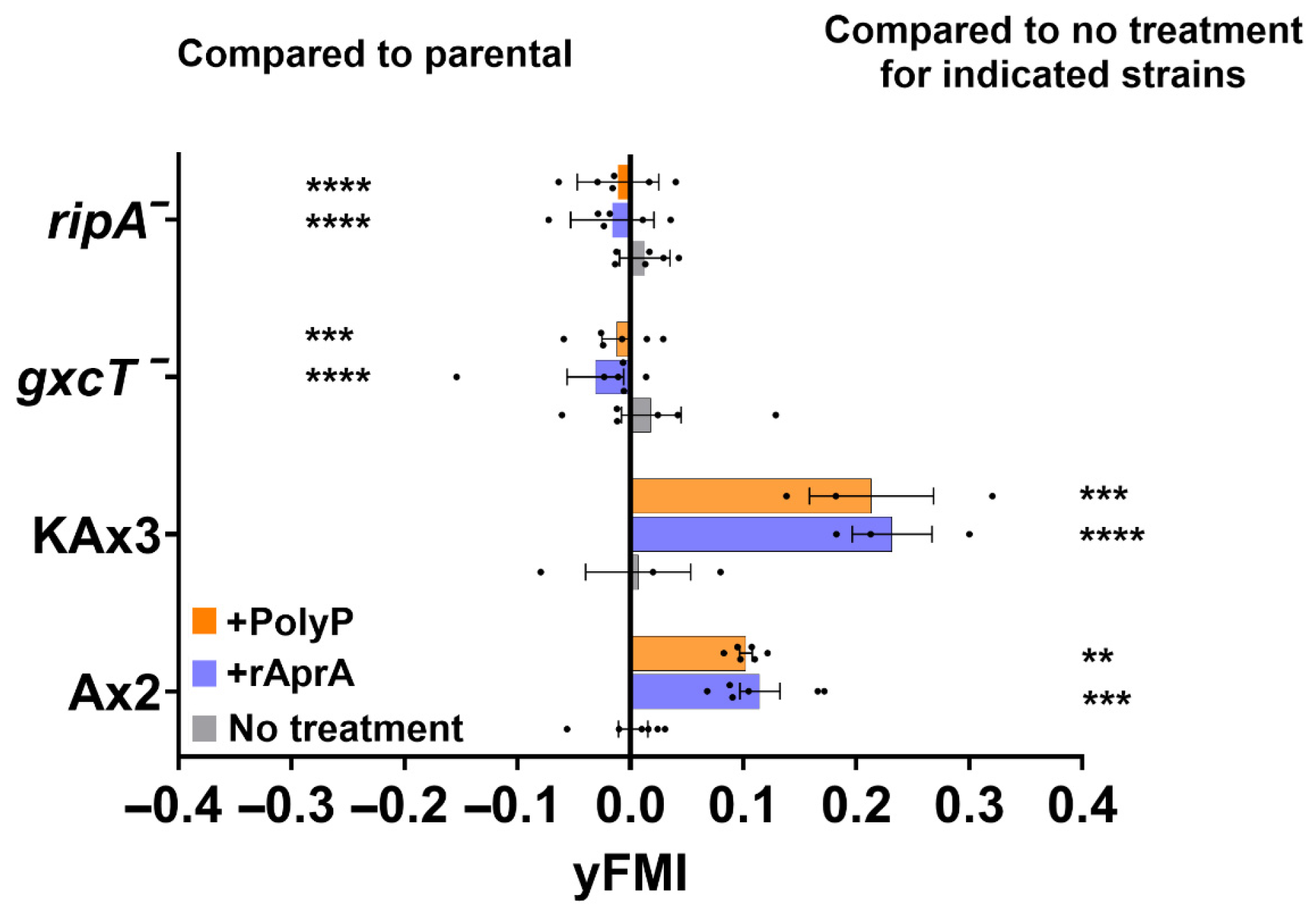

3.3. Two Proteins, GxcT and RipA, with Repellent-Decreased Phosphorylation Are Necessary for Chemorepulsion

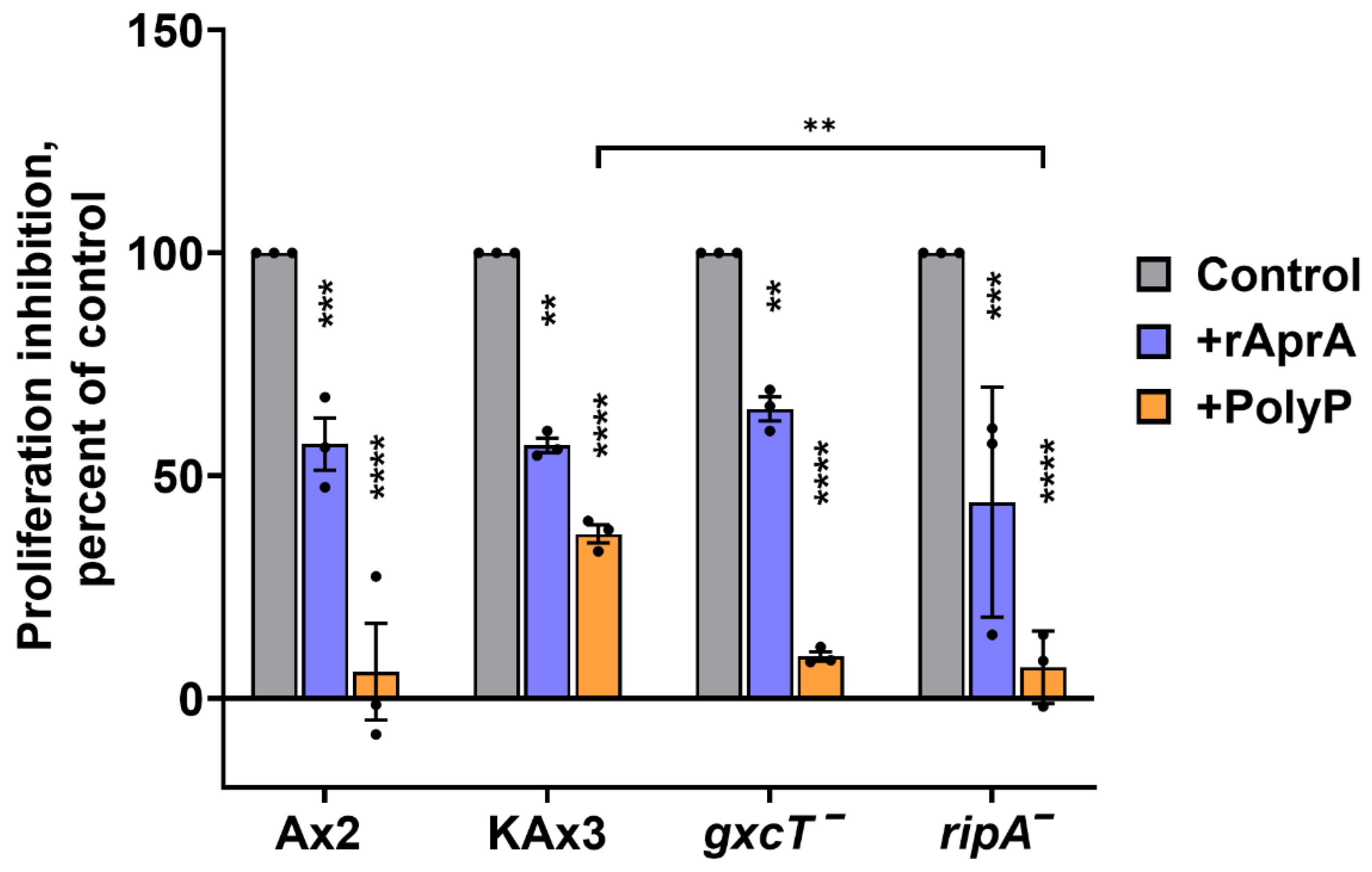

3.4. GxcT and RipA Do Not Mediate AprA and polyP Proliferation Inhibition

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shellard, A.; Mayor, R. All Roads Lead to Directional Cell Migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 852–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SenGupta, S.; Parent, C.A.; Bear, J.E. The principles of directed cell migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Feng, H. Deciphering Bacterial Chemorepulsion: The Complex Response of Microbes to Environmental Stimuli. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirolos, S.A.; Rijal, R.; Consalvo, K.M.; Gomer, R.H. Using Dictyostelium to Develop Therapeutics for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 710005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T. Chemorepulsion: Moving away from improper attractions. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R374–R376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzaro, S. The past, present and future of Dictyostelium as a model system. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2019, 63, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pears, C.J. Microbe Profile: Dictyostelium discoideum: Model system for development, chemotaxis and biomedical research. Microbiology 2021, 167, 001040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.E.; Gomer, R.H. A secreted protein is an endogenous chemorepellant in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 10990–10995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Herlihy, S.E.; Brito-Aleman, F.J.; Ting, J.H.; Janetopoulos, C.; Gomer, R.H. An Autocrine Proliferation Repressor Regulates Dictyostelium discoideum Proliferation and Chemorepulsion Using the G Protein-Coupled Receptor GrlH. mBio 2018, 9, e02443-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijal, R.; Consalvo, K.M.; Lindsey, C.K.; Gomer, R.H. An endogenous chemorepellent directs cell movement by inhibiting pseudopods at one side of cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirolos, S.A.; Gomer, R.H. A chemorepellent inhibits local Ras activation to inhibit pseudopod formation to bias cell movement away from the chemorepellent. Mol. Biol. Cell 2022, 33, ar9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sobky, M.H.; Rijal, R.; Gomer, R.H. Two endogenous Dictyostelium discoideum chemorepellents use different mechanisms to induce repulsion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2503168122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.H.; Tang, M.; Shi, C.; Iglesias, P.A.; Devreotes, P.N. An excitable signal integrator couples to an idling cytoskeletal oscillator to drive cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemenko, Y.; Lampert, T.J.; Devreotes, P.N. Moving towards a paradigm: Common mechanisms of chemotactic signaling in Dictyostelium and mammalian leukocytes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 3711–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, S.; Iwamoto, K.; Shin, D.Y.; Ueda, M. Spontaneous signal generation by an excitable system for cell migration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1373609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakthavatsalam, D.; Choe, J.M.; Hanson, N.E.; Gomer, R.H. A Dictyostelium chalone uses G proteins to regulate proliferation. BMC Biol. 2009, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess, P.M.; Tang, Y.; Gomer, R.H. The putative G protein-coupled receptor GrlD mediates extracellular polyphosphate sensing in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Rijal, R.; Zimmerhanzel, D.E.; McCullough, J.R.; Cadena, L.A.; Gomer, R.H. An Autocrine Negative Feedback Loop Inhibits Dictyostelium discoideum Proliferation through Pathways Including IP3/Ca2+. mBio 2021, 12, e0134721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, D.A.; Gomer, R.H. A secreted factor represses cell proliferation in Dictyostelium. Development 2005, 132, 4553–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess, P.M.; Gomer, R.H. Extracellular Polyphosphate Inhibits Proliferation in an Autocrine Negative Feedback Loop in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 20260–20269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, J.M.; Bakthavatsalam, D.; Phillips, J.E.; Gomer, R.H. Dictyostelium cells bind a secreted autocrine factor that represses cell proliferation. BMC Biochem. 2009, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.E.; Gomer, R.H. The ROCO kinase QkgA is necessary for proliferation inhibition by autocrine signals in Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryot. Cell 2010, 9, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.E.; Huang, E.; Shaulsky, G.; Gomer, R.H. The Putative bZIP Transcripton Factor BzpN Slows Proliferation and Functions in the Regulation of Cell Density by Autocrine Signals in Dictyostelium. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnita, C.E.; Washburne, A.; Martinez-Garcia, R.; Sgro, A.E.; Levin, S.A. Fitness tradeoffs between spores and nonaggregating cells can explain the coexistence of diverse genotypes in cellular slime molds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2776–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, A.J.; Schwartz, M.A.; Burridge, K.; Firtel, R.A.; Ginsberg, M.H.; Borisy, G.; Parsons, J.T.; Horwitz, A.R. Cell migration: Integrating signals from front to back. Science 2003, 302, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney, K.F.; Huang, C.H.; Devreotes, P.N. Eukaryotic chemotaxis: A network of signaling pathways controls motility, directional sensing, and polarity. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 39, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.J.; Ashworth, J.M. Growth of myxameobae of the cellular slime mould Dictyostelium discoideum in axenic culture. Biochem. J. 1970, 119, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nellen, W.; Silan, C.; Firtel, R.A. DNA-mediated transformation in Dictyostelium discoideum: Regulated expression of an actin gene fusion. Mol. Cell Biol. 1984, 4, 2890–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, P.; Dodson, R.J.; Basu, S.; Chisholm, R.L. One stop shop for everything Dictyostelium: DictyBase and the Dicty Stock Center in 2012. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 983, 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosel, D.; Khurana, T.; Majithia, A.; Huang, X.; Bhandari, R.; Kimmel, A.R. TOR complex 2 (TORC2) in Dictyostelium suppresses phagocytic nutrient capture independently of TORC1-mediated nutrient sensing. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Senoo, H.; Sesaki, H.; Iijima, M. Rho GTPases orient directional sensing in chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, P.; Kowal, A.S.; Gaudet, P.; Pilcher, K.E.; Chisholm, R.L. Protocols for growth and development of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschke, P.; Knecht, D.A.; Silale, A.; Traynor, D.; Williams, T.D.; Thomason, P.A.; Insall, R.H.; Chubb, J.R.; Kay, R.R.; Veltman, D.M. Rapid and efficient genetic engineering of both wild type and axenic strains of Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakthavatsalam, D.; Brock, D.A.; Nikravan, N.N.; Houston, K.D.; Hatton, R.D.; Gomer, R.H. The secreted Dictyostelium protein CfaD is a chalone. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 2473–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, T.M.; Chubb, J.R.; Saiardi, A. Developmental accumulation of inorganic polyphosphate affects germination and energetic metabolism in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rijal, R.; Gomer, R.H. Proteomic Analysis of Dictyostelium discoideum by Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2814, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevchenko, A.; Wilm, M.; Vorm, O.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996, 68, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappsilber, J.; Mann, M.; Ishihama, Y. Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1896–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thingholm, T.E.; Jorgensen, T.J.; Jensen, O.N.; Larsen, M.R. Highly selective enrichment of phosphorylated peptides using titanium dioxide. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Cox, J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 2301–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpievitch, Y.V.; Dabney, A.R.; Smith, R.D. Normalization and missing value imputation for label-free LC-MS analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Zidek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; Nair, S.; Natassia, C.; Yordanova, G.; Yuan, D.; Stroe, O.; Wood, G.; Laydon, A.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: Massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kempen, M.; Kim, S.S.; Tumescheit, C.; Mirdita, M.; Lee, J.; Gilchrist, C.L.M.; Söding, J.; Steinegger, M. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muinonen-Martin, A.J.; Veltman, D.M.; Kalna, G.; Insall, R.H. An improved chamber for direct visualisation of chemotaxis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M.A. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenbaum, E.; Rivero, F. Calponin homology domains at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 3543–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztul, E.; Chen, P.W.; Casanova, J.E.; Cherfils, J.; Dacks, J.B.; Lambright, D.G.; Lee, F.S.; Randazzo, P.A.; Santy, L.C.; Schurmann, A.; et al. ARF GTPases and their GEFs and GAPs: Concepts and challenges. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 1249–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, A.J. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, Z.; Alian, A.; Aqeilan, R.I. WW domain-containing proteins: Retrospectives and the future. Front. Biosci. 2012, 17, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Kalvakuri, S.; Bodmer, R.; Cox, R.T. Clueless, a protein required for mitochondrial function, interacts with the PINK1-Parkin complex in Drosophila. Dis. Model. Mech. 2015, 8, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, A.H.; Novick, P.J. Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxman, E.F.; Kunkel, E.J.; Butcher, E.C. Integrating conflicting chemotactic signals. The role of memory in leukocyte navigation. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 147, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomchik, K.J.; Devreotes, P.N. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate waves in Dictyostelium discoideum: A demonstration by isotope dilution—Fluorography. Science 1981, 212, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregor, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Masaki, N.; Sawai, S. The onset of collective behavior in social amoebae. Science 2010, 328, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.M.E.; Paschke, P.; Peak-Chew, S.; Williams, T.D.; Tweedy, L.; Skehel, M.; Stephens, E.; Chubb, J.R.; Kay, R.R. The Atypical MAP Kinase ErkB Transmits Distinct Chemotactic Signals through a Core Signaling Module. Dev. Cell 2019, 48, 491–505 e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.G.; Jackson, C.L. ARF family G proteins and their regulators: Roles in membrane transport, development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Parent, C.A.; Insall, R.; Firtel, R.A. A novel Ras-interacting protein required for chemotaxis and cyclic adenosine monophosphate signal relay in Dictyostelium. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 2829–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, A.; Lotfi, P.; Chavan, A.J.; Montano, N.M.; Bolourani, P.; Weeks, G.; Shen, Z.; Briggs, S.P.; Pots, H.; Van Haastert, P.J.; et al. The small GTPases Ras and Rap1 bind to and control TORC2 activity. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consalvo, K.M.; Kirolos, S.A.; Sestak, C.E.; Gomer, R.H. Sex-Based Differences in Human Neutrophil Chemorepulsion. J. Immunol. 2022, 209, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Uddin, S.Z.; Rijal, R.; Pilling, D.; Gomer, R.H. Phosphoproteomic Profiling Reveals Overlapping and Distinct Signaling Pathways in Dictyostelium discoideum in Response to Two Different Chemorepellents. Cells 2026, 15, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010060

Uddin SZ, Rijal R, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Phosphoproteomic Profiling Reveals Overlapping and Distinct Signaling Pathways in Dictyostelium discoideum in Response to Two Different Chemorepellents. Cells. 2026; 15(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleUddin, Salman Zahir, Ramesh Rijal, Darrell Pilling, and Richard H. Gomer. 2026. "Phosphoproteomic Profiling Reveals Overlapping and Distinct Signaling Pathways in Dictyostelium discoideum in Response to Two Different Chemorepellents" Cells 15, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010060

APA StyleUddin, S. Z., Rijal, R., Pilling, D., & Gomer, R. H. (2026). Phosphoproteomic Profiling Reveals Overlapping and Distinct Signaling Pathways in Dictyostelium discoideum in Response to Two Different Chemorepellents. Cells, 15(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010060