Modifying Factors of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: A Dorsoventral Perspective in Health and Disease

Abstract

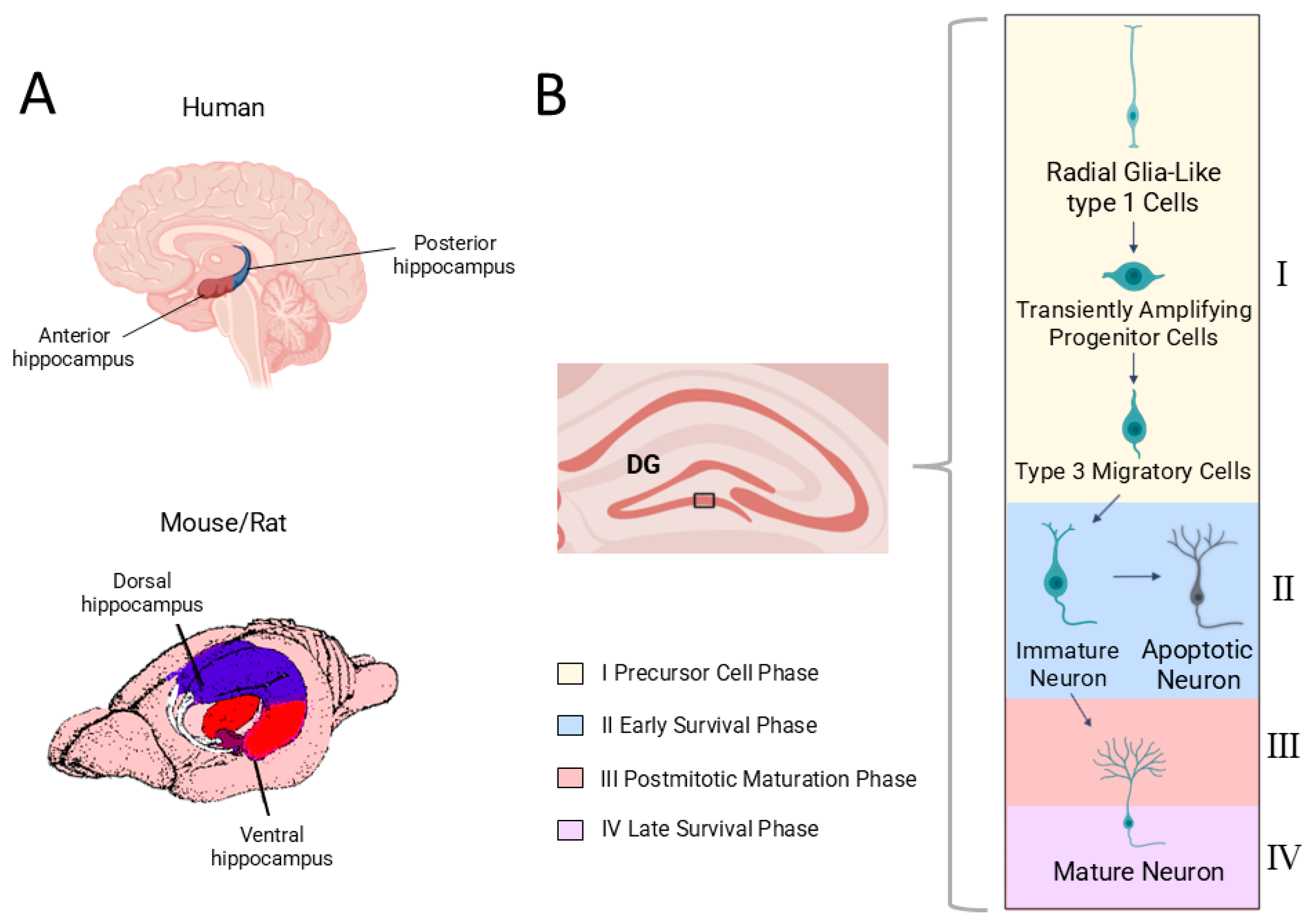

1. Introduction

2. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Humans

3. Factors Modifying Hippocampal Neurogenesis

3.1. Hormones

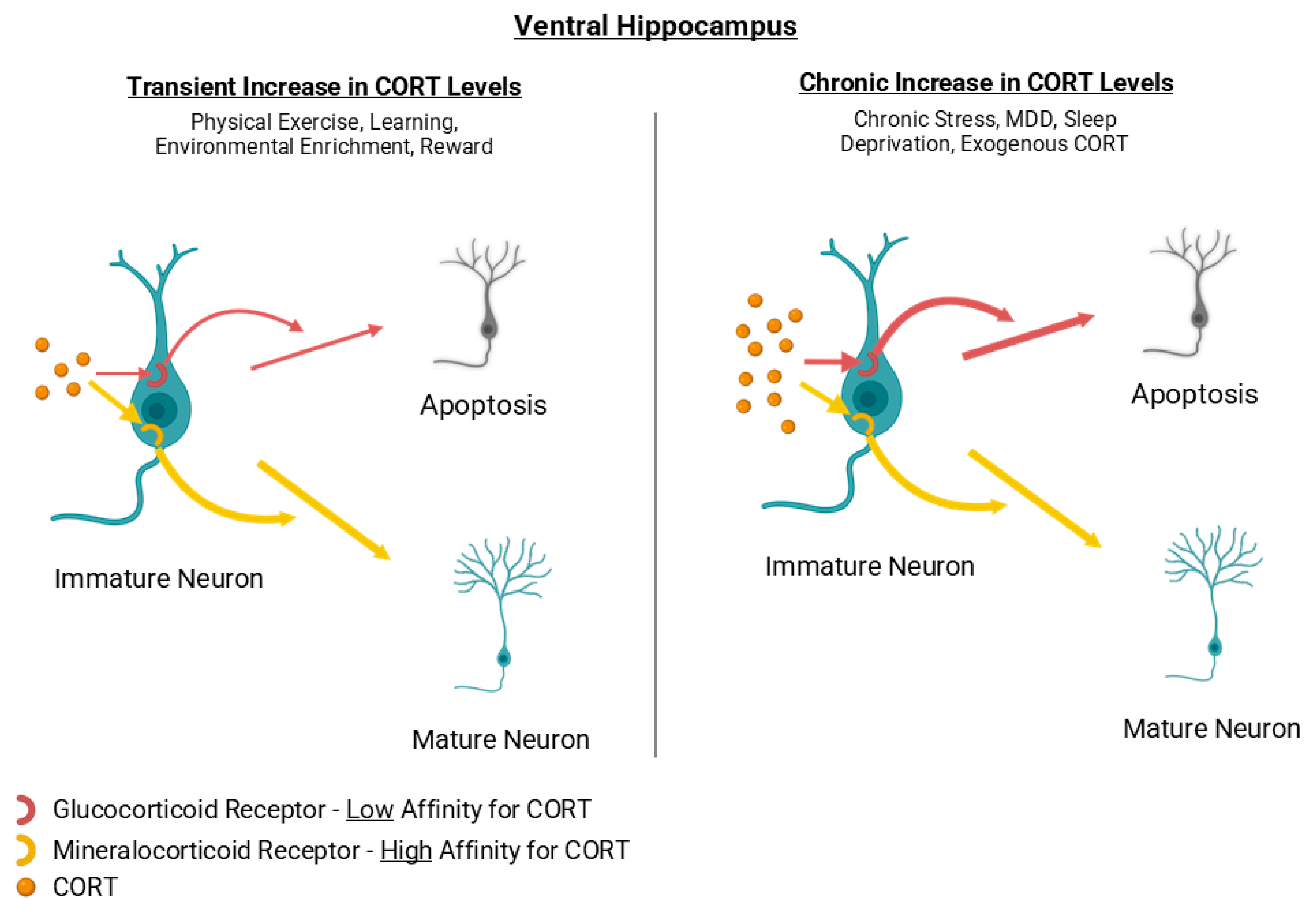

3.1.1. Cortisol/Corticosterone

3.1.2. Estrogens

3.1.3. Androgens

3.1.4. Oxytocin

3.1.5. Thyroid Hormones

3.1.6. Melatonin

3.1.7. Growth Hormone, IGF-1

3.1.8. Erythropoietin

3.2. Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

3.2.1. Physical Activity

3.2.2. Sleep

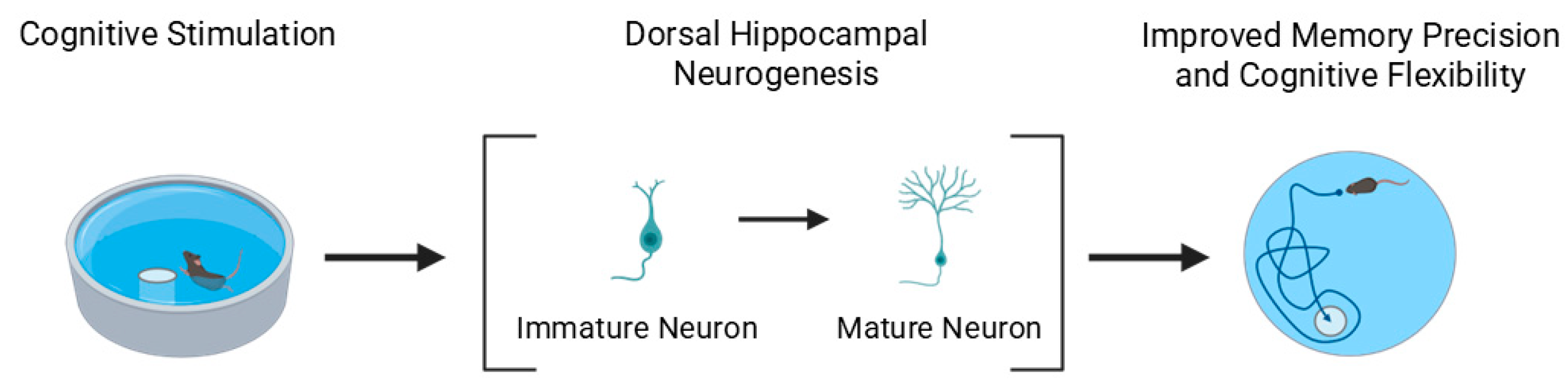

3.2.3. Learning

3.2.4. Rewarding Experience

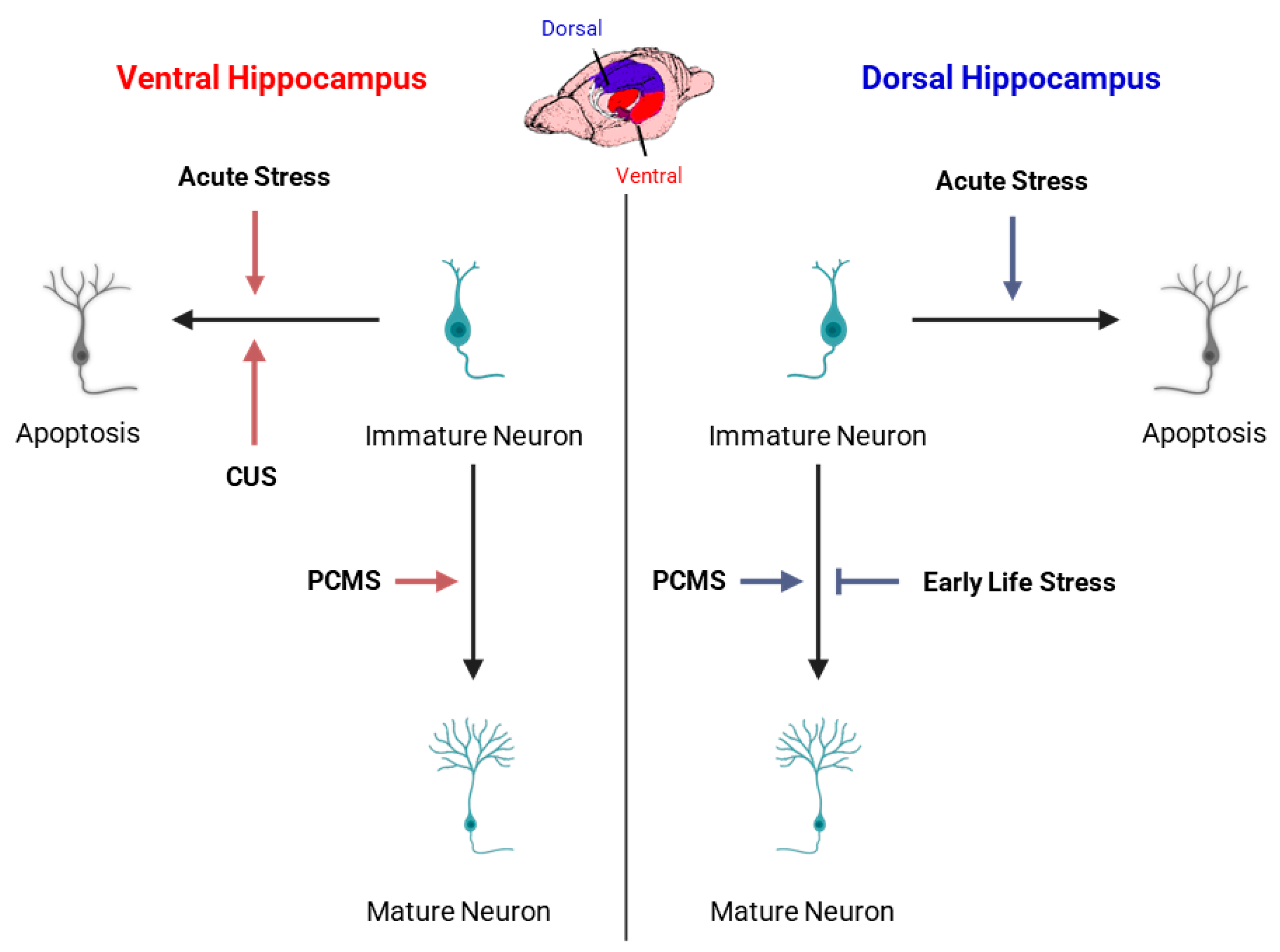

3.2.5. Stress

3.3. Diet and Nutritional Modifiers of AHN

3.3.1. Caloric Restriction & High-Fat Diet

3.3.2. Vitamins and Other Nutritional Factors

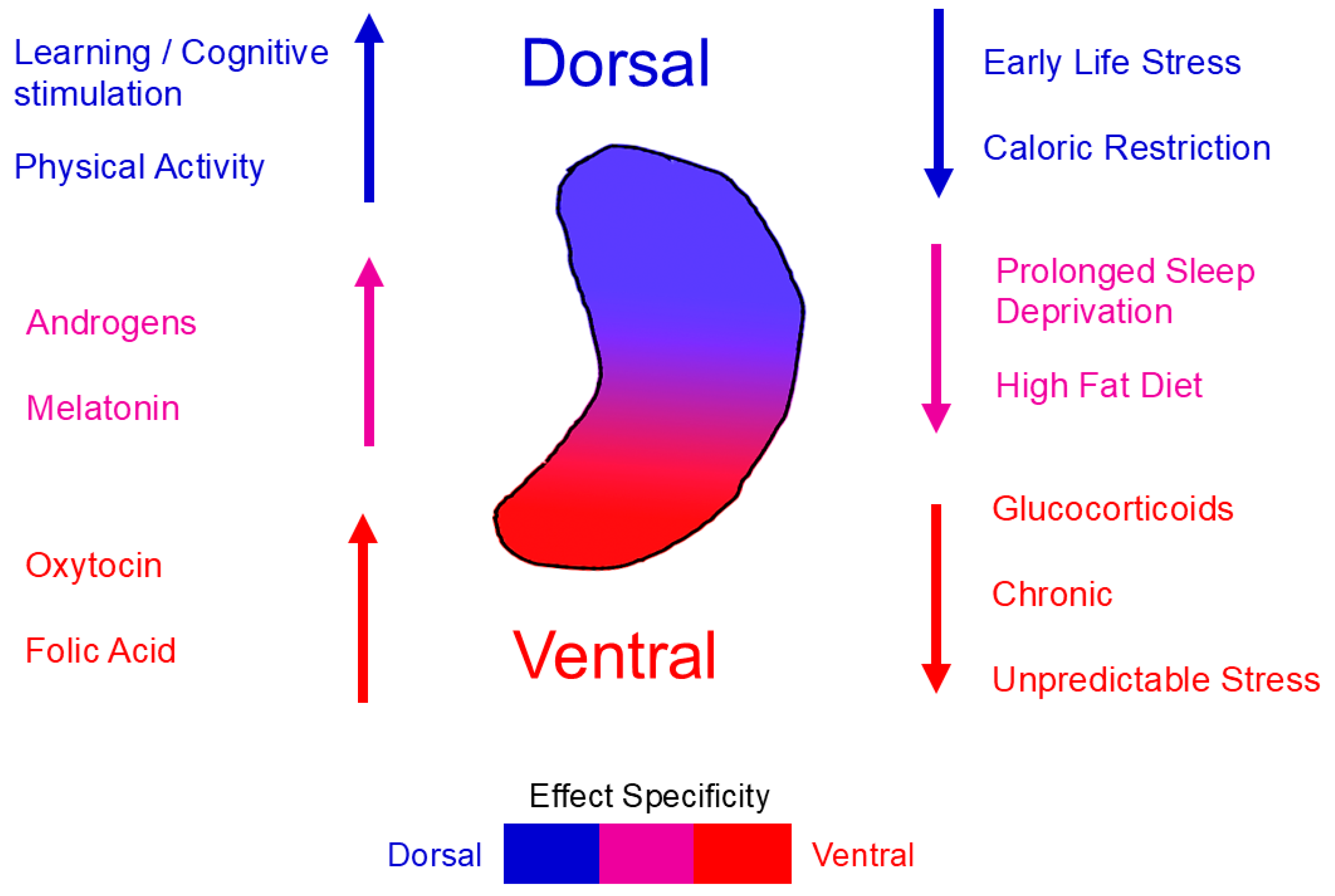

4. AHN from a Dorsoventral Perspective

4.1. Dorsoventral Heterogeneity of Neurogenesis

4.2. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Dorsoventral Differences

4.3. Functional Implications

4.4. Integrative Perspective

| Factor | Effect on Ventral AHN | Effect on Dorsal AHN | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning | No change/Decrease | Increase | [156,234] |

| Chronic Unpredictable Stress | Decrease | No change | [169] |

| Early Life Stress | No change | Decrease | [171] |

| Physical Activity | No change/Increase | Increase | [41,90,133] |

| Prolonged Sleep Deprivation | Decrease | Decrease | [140] |

| Caloric Restriction | Increase/Decrease | Decrease | [180] |

| High-Fat Diet | Decrease | Decrease | [186] |

| Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) | No data | Increase | [194,235] |

| Flavonoids | No Change | Increase | [59] |

| Folic Acid | Increase | No change/Increase | [193] |

| Cortisol | Decrease 1 | No change/Decrease 1 | [39] |

| Estrogens | Increase/No change/ Decrease | Increase/Decrease 2 | [53,59] |

| Androgens | Increase | Increase | [64] |

| Oxytocin | Increase | No change | [73] |

| Melatonin | Increase | Increase | [90] |

5. Implications of Dorsoventral AHN Modulation in Neuropsychiatric and Neurodegenerative Disorders

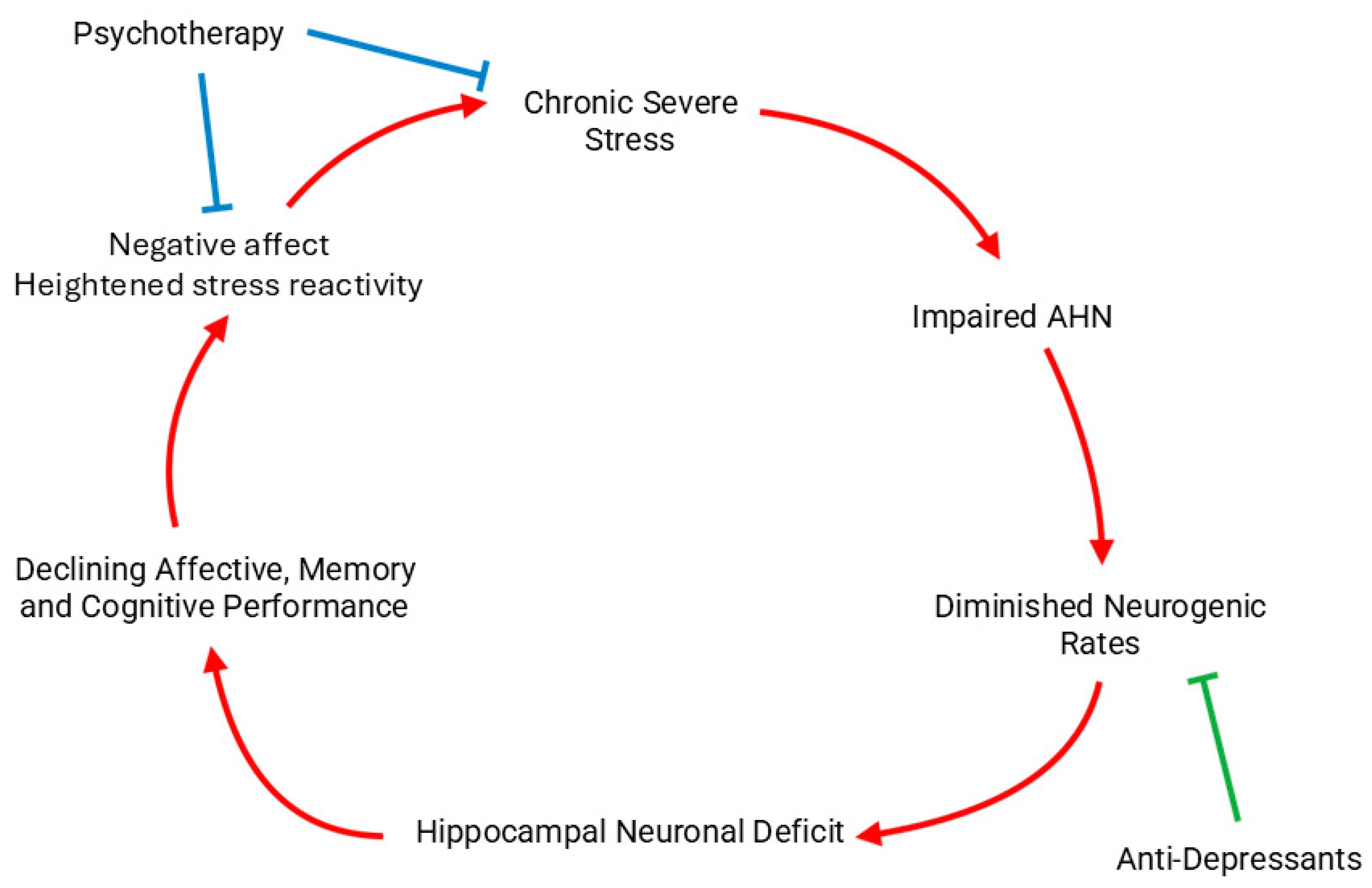

5.1. Major Depressive Disorder & Anxiety Disorders

5.2. Schizophrenia

5.3. Alzheimer’s Disease

| Factor | Protective/Risk Factor for AD | Effect on AHN | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning/Education | Protective | Increase (Dorsal) | [149,268] |

| Physical Activity | Protective | Increase (Dorsal) | [41,270] |

| High-Fat diet | Risk Factor | Decrease | [185,187,271] |

| Sleep Deprivation | Risk Factor | Decrease | [140,272] |

| Stress/Depression | Risk Factor | Decrease (Ventral) | [167,168,240,273] |

5.4. Addiction

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHΝ | Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis |

| BrdU | Bromodeoxyuridine |

| NSC | Neural Stem Cell |

| TAP | Transiently Amplifying Progenitor |

| SGZ | Subgranular Zone |

| DG | Dentate Gyrus |

| CORT | Cortisol/Corticosterone |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal |

| GR | Glucocorticoid Receptor |

| MR | Mineralocorticoid Receptor |

| ER | Estrogen Receptor |

| GPER1 | G Protein-coupled Estrogen Receptor 1 |

| AR | Androgen Receptor |

| OXTR | Oxytocin Receptor |

| TH | Thyroid Hormone |

| TR | Thyroid Hormone Receptor |

| GH | Growth Hormone |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 |

| IGF1R | Insulin Growth Factor 1 Receptor |

| GHR | Growth Hormone Receptor |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| EPO-R | Erythropoietin Receptor |

| BDNF | Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| REM | Rapid Eye Movement |

| NREM | Non-Rapid Eye Movement |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| OFC | Orbitofrontal Cortex |

| ACC | Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| vmPFC | Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex |

| dlPFC | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex |

| VTA | Ventral Tegmental Area |

| NaC | Nucleus Accumbens |

| CRH | Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| CUS | Chronic Unpredictable Stress |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| PCMS | Predictable Chronic Mild Stress |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| LPSs | Lipopolysaccharides |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| RA | Retinoic Acid |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| SSRI | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor |

| TCAs | Tricyclic Antidepressants |

| MAOI | Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor |

| 5-HT | 5-Hydroxytryptamine |

| ECT | Electroconvulsive Therapy |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| MDMA | 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine |

References

- Altman, J. Are New Neurons Formed in the Brains of Adult Mammals? Science 1962, 135, 1127–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, J.; Das, G.D. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965, 124, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, M.; Fulmore, C.A.; Tartt, A.N.; Simeon, L.R.; Pavlova, I.; Poposka, V.; Rosoklija, G.B.; Stankov, A.; Arango, V.; Dwork, A.J.; et al. Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 589–599.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, M.K.; Musaraca, K.; Disouky, A.; Shetti, A.; Bheri, A.; Honer, W.G.; Kim, N.; Dawe, R.J.; Bennett, D.A.; Arfanakis, K.; et al. Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists in Aged Adults and Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 974–982.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, E.P.; Flor-García, M.; Terreros-Roncal, J.; Rábano, A.; Cafini, F.; Pallas-Bazarra, N.; Ávila, J.; Llorens-Martín, M. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, S.; Kennedy, B.C.; Zhang, D.Y.; Bond, A.M.; Sun, Y.; Jacob, F.; Lu, L.; Hu, P.; et al. Molecular landscapes of human hippocampal immature neurons across lifespan. Nature 2022, 607, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, M.; Yang, M.; Zeng, B.; Qiu, W.; Ma, Q.; Jing, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, B.; Yin, C.; et al. Transcriptome dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in macaques across the lifespan and aged humans. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, E.B.; Dimitrova, M.B.; Ivanov, I.P.; Pavlova, V.G.; Dimitrova, S.G.; Kadiysky, D.S. Effect of acute hypoxic shock on the rat brain morphology and tripeptidyl peptidase I activity. Acta Histochem. 2016, 118, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitru, I.; Paterlini, M.; Zamboni, M.; Ziegenhain, C.; Giatrellis, S.; Saghaleyni, R.; Björklund, Å.; Alkass, K.; Tata, M.; Druid, H.; et al. Identification of proliferating neural progenitors in the adult human hippocampus. Science 2025, 389, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrells, S.F.; Paredes, M.F.; Cebrian-Silla, A.; Sandoval, K.; Qi, D.; Kelley, K.W.; James, D.; Mayer, S.; Chang, J.; Auguste, K.I.; et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 2018, 555, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, T.; Hori, T.; Miyata, H.; Maehara, M.; Namba, T.; Seki, T.; Hori, T.; Miyata, H.; Maehara, M.; Namba, T. Analysis of proliferating neuronal progenitors and immature neurons in the human hippocampus surgically removed from control and epileptic patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, A.; Arellano, J.I.; Rakic, P.; Duque, A.; Arellano, J.I.; Rakic, P. An assessment of the existence of adult neurogenesis in humans and value of its rodent models for neuropsychiatric diseases. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 27, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanirati, G.; Shetty, P.A.; Shetty, A.K. Neural stem cells persist to generate new neurons in the hippocampus of adult and aged human brain—Fiction or accurate? Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurkowski, M.P.; Bettio, L.; Woo, E.K.; Patten, A.; Yau, S.-Y.; Gil-Mohapel, J. Beyond the Hippocampus and the SVZ: Adult Neurogenesis Throughout the Brain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 576444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C.M.; Burgess, N.; Bird, C.M.; Burgess, N. The hippocampus and memory: Insights from spatial processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweatt, J.D. Hippocampal function in cognition. Psychopharmacology 2004, 174, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, J.L.; Bridge, D.J.; Cohen, N.J.; Walker, J.A. A closer look at the hippocampus and memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2017, 21, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, H.; Tong, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Q.; Yan, B. Emotion Regulation of Hippocampus Using Real-Time fMRI Neurofeedback in Healthy Human. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, A.; Hen, R.; Sahay, A.; Hen, R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheirbek, M.A.; Hen, R. Dorsal vs Ventral Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Implications for Cognition and Mood. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar-Locatelli, S.; Ceglia, M.d.; Mañas-Padilla, M.C.; Rodriguez-Pérez, C.; Castilla-Ortega, E.; Castro-Zavala, A.; Rivera, P. Nutrition and adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus: Does what you eat help you remember? Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1147269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenfeld, T.J.; Gould, E. Stress, stress hormones, and adult neurogenesis. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 233, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sanchis, C.; Brock, O.; Winsky-Sommerer, R.; Thuret, S. Modulation of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis by Sleep: Impact on Mental Health. Front. Neural Circuits 2017, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.S.; Perfilieva, E.; Björk-Eriksson, T.; Alborn, A.M.; Nordborg, C.; Peterson, D.A.; Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, K.L.; Bergmann, O.; Alkass, K.; Bernard, S.; Salehpour, M.; Huttner, H.B.; Boström, E.; Westerlund, I.; Vial, C.; Buchholz, B.A.; et al. Dynamics of Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Adult Humans. Cell 2013, 153, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempermann, G.; Song, H.; Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the Adult Hippocampus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a018812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, G.; Reuter, K.; Steiner, B.; Brandt, M.D.; Jessberger, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kempermann, G. Subpopulations of proliferating cells of the adult hippocampus respond differently to physiologic neurogenic stimuli. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003, 467, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, B.; Klempin, F.; Wang, L.; Kott, M.; Kettenmann, H.; Kempermann, G. Type-2 cells as link between glial and neuronal lineage in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Glia 2006, 54, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloet, E.R.D.; Reul, J.M.H.M. Feedback action and tonic influence of corticosteroids on brain function: A concept arising from the heterogeneity of brain receptor systems. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1987, 12, 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menuet, D.L.; Lombès, M. The neuronal mineralocorticoid receptor: From cell survival to neurogenesis. Steroids 2014, 91, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaltink, D.-J.; Vreugdenhil, E.; Saaltink, D.-J.; Vreugdenhil, E. Stress, glucocorticoid receptors, and adult neurogenesis: A balance between excitation and inhibition? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2499–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, P.; Kretz, O.; Wolfer, D.P.; Berger, S.; Tronche, F.; Reichardt, H.M.; Kellendonk, C.; Lipp, H.P.; Schmid, W.; Schütz, G. Genetic disruption of mineralocorticoid receptor leads to impaired neurogenesis and granule cell degeneration in the hippocampus of adult mice. EMBO Rep. 2000, 1, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesmundo, I.; Villanova, T.; Gargantini, E.; Arvat, E.; Ghigo, E.; Granata, R. The Mineralocorticoid Agonist Fludrocortisone Promotes Survival and Proliferation of Adult Hippocampal Progenitors. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Cao, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Duan, J.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, T.; et al. Corticosterone Impairs Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Behaviors through p21-Mediated ROS Accumulation. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.S.; Lee, S.H.; Moon, H.J.; So, Y.H.; Jang, H.J.; Lee, K.-H.; Ahn, C.; Jung, E.-M. Prolonged stress response induced by chronic stress and corticosterone exposure causes adult neurogenesis inhibition and astrocyte loss in mouse hippocampus. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 208, 110903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummelte, S.; Galea, L.A.M. Chronic high corticosterone reduces neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult male and female rats. Neuroscience 2010, 168, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, E.; Cameron, H.; Daniels, D.; Woolley, C.; McEwen, B. Adrenal hormones suppress cell division in the adult rat dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 1992, 12, 3642–3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, H.A.; Gould, E. Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience 1994, 61, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levone, B.R.; Codagnone, M.G.; Moloney, G.M.; Nolan, Y.M.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Leary, O.F. Adult-born neurons from the dorsal, intermediate, and ventral regions of the longitudinal axis of the hippocampus exhibit differential sensitivity to glucocorticoids. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 3240–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droste, S.K.; Gesing, A.; Ulbricht, S.; Müller, M.B.; Linthorst, A.C.E.; Reul, J.M.H.M. Effects of long-term voluntary exercise on the mouse hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 3012–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, M.R.; Aumont, A.; Décary, S.; Bergeron, R.; Fernandes, K.J.L. Prolonged voluntary wheel-running stimulates neural precursors in the hippocampus and forebrain of adult CD1 mice. Hippocampus 2009, 19, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncek, F.; Duncko, R.; Johansson, B.B.; Jezova, D. Effect of environmental enrichment on stress related systems in rats. J. Neuroendocr. 2004, 16, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veena, J.; Srikumar, B.N.; Raju, T.R.; Rao, B.S.S. Exposure to enriched environment restores the survival and differentiation of new born cells in the hippocampus and ameliorates depressive symptoms in chronically stressed rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 455, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanti, A.; Rainer, Q.; Minier, F.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C. Differential environmental regulation of neurogenesis along the septo-temporal axis of the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 2012, 63, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Jaime, H.; Vázquez-Palacios, G.; Arteaga-Silva, M.; Retana-Márquez, S. Hormonal responses to different sexually related conditions in male rats. Horm. Behav. 2006, 49, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuner, B.; Mendolia-Loffredo, S.; Kozorovitskiy, Y.; Samburg, D.; Gould, E.; Shors, T.J. Learning Enhances the Survival of New Neurons beyond the Time when the Hippocampus Is Required for Memory. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 7477–7481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odaka, H.; Adachi, N.; Numakawa, T. Impact of glucocorticoid on neurogenesis. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandam, L.S.; Brazel, M.; Zhou, M.; Jhaveri, D.J. Cortisol and Major Depressive Disorder—Translating Findings from Humans to Animal Models and Back. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almey, A.; Milner, T.A.; Brake, W.G. Estrogen receptors in the central nervous system and their implication for dopamine-dependent cognition in females. Horm. Behav. 2015, 74, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfvinge, K.; Krause, D.N.; Maddahi, A.; Edvinsson, J.C.A.; Edvinsson, L.; Haanes, K.A. Estrogen receptors α, β and GPER in the CNS and trigeminal system—Molecular and functional aspects. J. Headache Pain. 2020, 21, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Niu, J.-G.; Kong, X.-R.; Mi, X.-J.; Liu, Q.; Chen, F.-F.; Rong, W.-F.; Liu, J. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 deficiency impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice with schizophrenia. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2023, 132, 102319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanapat, P.; Hastings, N.B.; Reeves, A.J.; Gould, E. Estrogen stimulates a transient increase in the number of new neurons in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 5792–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, S.; Mohammad, A.; Wen, Y.; Burrowes, A.A.B.; Blankers, S.A.; Galea, L.A.M. Estrogens dynamically regulate neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult female rats. Hippocampus 2024, 34, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanapat, P.; Hastings, N.B.; Gould, E. Ovarian steroids influence cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat in a dose- and time-dependent manner. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 481, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, R.E.S.; Barha, C.K.; Galea, L.A.M. 17β-Estradiol, but not estrone, increases the survival and activation of new neurons in the hippocampus in response to spatial memory in adult female rats. Horm. Behav. 2013, 63, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormerod, B.K.; Lee, T.T.-Y.; Galea, L.A.M. Estradiol enhances neurogenesis in the dentate gyri of adult male meadow voles by increasing the survival of young granule neurons. Neuroscience 2004, 128, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.; Wainwright, S.R.; Galea, L.A.M. Sex hormones and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: Regulation, implications, and potential mechanisms. Front. Neuroendocr. 2016, 41, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiton, J.A.; Wong, S.J.; Galea, L.A. Chronic aromatase inhibition increases ventral hippocampal neurogenesis in middle-aged female mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 106, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, J.; Hatabe, J.; Tankyo, K.; Jinno, S. Cell type- and region-specific enhancement of adult hippocampal neurogenesis by daidzein in middle-aged female mice. Neuropharmacology 2016, 111, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kley, H.K.; Deselaers, T.; Peerenboom, H.; Kruskemper, H.L. Enhanced conversion of androstenedione to estrogens in obese males. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1980, 51, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Guterman, P.; Lieblich, S.E.; Wainwright, S.R.; Chow, C.; Chaiton, J.A.; Watson, N.V.; Galea, L.A.M. Androgens Enhance Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Males but Not Females in an Age-Dependent Manner. Endocrinology 2019, 160, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spritzer, M.D.; Galea, L.A.M. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone, but not estradiol, enhance survival of new hippocampal neurons in adult male rats. Dev. Neurobiol. 2007, 67, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamson, D.; Wainwright, S.; Taylor, J.; Jones, B.; Watson, N.; Galea, L. Androgens increase survival of adult-born neurons in the dentate gyrus by an androgen receptor-dependent mechanism in male rats. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3294–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift-Gallant, A.; Duarte-Guterman, P.; Hamson, D.K.; Ibrahim, M.; Monks, D.A.; Galea, L.A.M. Neural androgen receptors affect the number of surviving new neurones in the adult dentate gyrus of male mice. J. Neuroendocr. 2018, 30, e12578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.G.N.; Fernandes, J.; Campos, D.V.; Cassilhas, R.C.; Viana, G.M.; D’Almeida, V.; Rêgo, M.K.d.M.; Buainain, P.I.; Cavalheiro, E.A.; Arida, R.M. The beneficial effects of strength exercise on hippocampal cell proliferation and apoptotic signaling is impaired by anabolic androgenic steroids. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 50, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, L.; Wainwright, S.; Roes, M.; Duarte-Guterman, P.; Chow, C.; Hamson, D. Sex, hormones and neurogenesis in the hippocampus: Hormonal modulation of neurogenesis and potential functional implications. J. Neuroendocr. 2013, 25, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabori, N.; Stewart, L.; Znamensky, V.; Romeo, R.; Alves, S.; McEwen, B.; Milner, T. Ultrastructural evidence that androgen receptors are located at extranuclear sites in the rat hippocampal formation. Neuroscience 2005, 130, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimpl, G.; Fahrenholz, F. The oxytocin receptor system: Structure, function, and regulation. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 629–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froemke, R.C.; Young, L.J. Oxytocin, Neural Plasticity, and Social Behavior. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 44, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, R.; Kiyama, H.; Kimura, T.; Araki, T.; Maeno, H.; Tanizawa, O.; Tohyama, M. Localization of oxytocin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat brain. Endocrinology 1993, 133, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccia, M.L.; Petrusz, P.; Suzuki, K.; Marson, L.; Pedersen, C.A. Immunohistochemical localization of oxytocin receptors in human brain. Neuroscience 2013, 253, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monari, P.K.; Herro, Z.J.; Bymers, J.; Marler, C.A. Chronic intranasal oxytocin increases acoustic eavesdropping and adult neurogenesis. Horm. Behav. 2023, 156, 105443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuner, B.; Caponiti, J.M.; Gould, E. Oxytocin stimulates adult neurogenesis even under conditions of stress and elevated glucocorticoids. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-C.; Huang, C.-C.; Nishimori, K.; Hsu, K.-S. Oxytocin stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis via oxytocin receptor expressed in CA3 pyramidal neurons. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte-Guterman, P.; Lieblich, S.E.; Qiu, W.; Splinter, J.E.J.; Go, K.A.; Casanueva-Reimon, L.; Galea, L.A.M. Oxytocin has sex-specific effects on social behaviour and hypothalamic oxytocin immunoreactive cells but not hippocampal neurogenesis in adult rats. Horm. Behav. 2020, 122, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacker, C.; Hen, R. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive flexibility—Linking memory and mood. Nat. Rev. 2017, 18, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, O.; Cryan, J. A ventral view on antidepressant action: Roles for adult hippocampal neurogenesis along the dorsoventral axis. Trends Pharm. Sci. 2014, 35, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Yu, C.; Dong, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, D. Tau aggravates stress-induced anxiety by inhibiting adult ventral hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Cereb. Cortex 2023, 33, 3853–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.B.; Koenig, R.J. Expression of erbAα and β mRNAs in regions of adult rat brain. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1990, 70, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, K.; Dudazy, S.; van Hogerlinden, M.; Nordström, K.; Mittag, J.; Vennström, B. The Thyroid Hormone Receptor α1 Protein Is Expressed in Embryonic Postmitotic Neurons and Persists in Most Adult Neurons. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, L.A.; Ladiwala, U.; Daniel, S.M.; Agashe, S.; Vaidya, R.A.; Vaidya, V.A. Thyroid hormone regulates hippocampal neurogenesis in the adult rat brain. Moll. Cell. Neurosci. 2005, 29, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, R.; Desouza, L.A.; Nanavaty, I.N.; Kernie, S.G.; Vaidya, V.A. Thyroid Hormone Accelerates the Differentiation of Adult Hippocampal Progenitors. J. Neuroendocr. 2012, 24, 1259–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Hogerlinden, M.v.; Wallis, K.; Ghosh, H.; Nordstrom, K.; Vennstrom, B.; Vaidya, V.A. Unliganded thyroid hormone receptor alpha1 impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis. FASEB 2010, 24, 4793–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J. Thyroid hormone receptors in brain development and function. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 3, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagamasbad, P.D.; Espina, J.E.C.; Knoedler, J.R.; Subramani, A.; Harden, A.J.; Denver, R.J. Coordinated transcriptional regulation by thyroid hormone and glucocorticoid interaction in adult mouse hippocampus-derived neuronal cells. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolet, M.; Buisine, N.; Scharwatt, M.; Duvernois-Berthet, E.; Buchholz, D.R.; Sachs, L.M. Crosstalk between Thyroid Hormone and Corticosteroid Signaling Targets Cell Proliferation in Xenopus tropicalis Tadpole Liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.Y.; Leong, M.K.; Liang, H.; Paxinos, G.; Ng, K.Y.; Leong, M.K.; Liang, H.; Paxinos, G. Melatonin receptors: Distribution in mammalian brain and their respective putative functions. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017, 222, 2921–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, K.; Butte, M.D.; Pappas, B.A. Melatonin promotes neurogenesis in dentate gyrus in the pinealectomized rat. J. Pineal Res. 2009, 47, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Rodríguez, G.; Klempin, F.; Babu, H.; Benítez-King, G.; Kempermann, G.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, G.; Klempin, F.; Babu, H.; Benítez-King, G.; Kempermann, G. Melatonin Modulates Cell Survival of New Neurons in the Hippocampus of Adult Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 2180–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Somera-Molina, K.C.; Hudson, R.L.; Dubocovich, M.L. Melatonin potentiates running wheel-induced neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult C3H/HeN mice hippocampus. J. Pineal Res. 2012, 54, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Rodriguez, G.; Ortíz-López, L.; Domínguez-Alonso, A.; Benítez-King, G.A.; Kempermann, G. Chronic treatment with melatonin stimulates dendrite maturation and complexity in adult hippocampal neurogenesis of mice. J. Pineal Res. 2011, 50, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rodríguez, G.B.; Palacios-Cabriales, D.M.; Ortiz-López, L.; Estrada-Camarena, E.M.; Vega-Rivera, N.M. Melatonin Modulates Dendrite Maturation and Complexity in the Dorsal- and Ventral-Dentate Gyrus Concomitantly with Its Antidepressant-Like Effect in Male Balb/C Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongchitrat, P.; Lansubsakul, N.; Kamsrijai, U.; Sae-Ung, K.; Mukda, S.; Govitrapong, P. Melatonin attenuates the high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced reduction in rat hippocampal neurogenesis. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 100, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruksee, N.; Tongjaroenbuangam, W.; Mahanam, T.; Govitrapong, P. Melatonin pretreatment prevented the effect of dexamethasone negative alterations on behavior and hippocampal neurogenesis in the mouse brain. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 143, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Niu, P.; Chen, T. Melatonin mitigates manganese-induced neural damage via modulation of gut microbiota-metabolism in mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Yoo, K.-Y.; Choi, J.H.; Park, O.K.; Hwang, I.K.; Kwon, Y.-G.; Kim, Y.-M.; Won, M.-H. Melatonin’s protective action against ischemic neuronal damage is associated with up-regulation of the MT2 melatonin receptor. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chern, C.-M.; Liao, J.-F.; Wang, Y.-H.; Shen, Y.-C. Melatonin ameliorates neural function by promoting endogenous neurogenesis through the MT2 melatonin receptor in ischemic-stroke mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 1634–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Contino, J.E.; Díaz-Sánchez, E.; Mirchandani-Duque, M.; Sánchez-Pérez, J.A.; Barbancho, M.A.; López-Salas, A.; García-Casares, N.; Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Narváez, M. GALR2 and Y1R agonists intranasal infusion enhanced adult ventral hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressant-like effects involving BDNF actions. J. Cell Physiol. 2023, 238, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.W.-H.; Cheung, K.-K.; Ngai, S.P.-C.; Tsang, H.W.-H.; Lau, B.W.-M. Protective Effects of Melatonin on Neurogenesis Impairment in Neurological Disorders and Its Relevant Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, D.I.; Shkodina, A.D.; Hasan, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; Kazmi, S.K.; Chopra, H.; Bhutra, P.; Baig, A.A.; Skrypnikov, A.M. Melatonergic Receptors (Mt1/Mt2) as a Potential Additional Target of Novel Drugs for Depression. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 2909–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasinski, F.; Klein, M.O.; Bittencourt, J.C.; Metzger, M.; Donato, J. Distribution of growth hormone-responsive cells in the brain of rats and mice. Brain Res. 2021, 1751, 147189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, V.C.; Gluckman, P.D.; Feldman, E.L.; Werther, G.A. The Insulin-Like Growth Factor System and Its Pleiotropic Functions in Brain. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 916–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberg, N.D.; Lind, J.; Isgaard, J.; Kuhn, H.G. Peripheral growth hormone induces cell proliferation in the intact adult rat brain. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2010, 20, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åberg, M.A.I.; Åberg, N.D.; Hedbäcker, H.; Oscarsson, J.; Eriksson, P.S. Peripheral infusion of IGF-I selectively induces neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 2896–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, M.A.I.; Aberg, N.D.; Palmer, T.D.; Alborn, A.-M.; Carlsson-Skwirut, C.; Bang, P.; Rosengren, L.E.; Olsson, T.; Gage, F.H.; Eriksson, P.S. IGF-I has a direct proliferative effect in adult hippocampal progenitor cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003, 24, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.F.; Aberg, M.A.I.; Nilsson, M.; Eriksson, P.S. Insulin-like growth factor-I and neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2002, 134, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, D.G.; Vukovic, J.; Waters, M.J.; Bartlett, P.F. GH Mediates Exercise-Dependent Activation of SVZ Neural Precursor Cells in Aged Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Vaynman, S.; Akhavan, M.; Ying, Z.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. Insulin-like growth factor I interfaces with brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated synaptic plasticity to modulate aspects of exercise-induced cognitive function. Neuroscience 2006, 140, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, J.L.; Carro, E.; Torres-Alemán, I. Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor I Mediates Exercise-Induced Increases in the Number of New Neurons in the Adult Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaka, Y.; Yashiro, R. Molecular Regulation and Therapeutic Applications of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor–Tropomyosin-Related Kinase B Signaling in Major Depressive Disorder Though Its Interaction with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and N-Methyl-D-Aspartic Acid Receptors: A Narrative Review. Biologics 2025, 5, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Udo, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Kino, T.; Ohnuki, K.; Mizunoya, W.; Mukuda, T.; Sugiyama, H. Enhanced Adult Neurogenesis and Angiogenesis and Altered Affective Behaviors in Mice Overexpressing Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor 120. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 14522–14536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Bezanilla, S.; Beard, D.J.; Hood, R.J.; Åberg, N.D.; Crock, P.; Walker, F.R.; Nilsson, M.; Isgaard, J.; Ong, L.K. Growth Hormone Increases BDNF and mTOR Expression in Specific Brain Regions after Photothrombotic Stroke in Mice. Neural Plast. 2022, 2022, 9983042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, K.G.; Olberg, A.; Lande, A.; Kjelstrup, K.B.; Brun, V.H. Hippocampal growth hormone modulates relational memory and the dendritic spine density in CA1. Learn. Mem. 2020, 27, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, C.T.; Asavaritikrai, P.; Teng, R.; Jia, Y. Role of erythropoietin in the brain. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2007, 64, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabpoor, Z.; Hamidi, G.; Rashidi, B.; Shabrang, M.; Alaei, H.; Sharifi, M.R.; Salami, M.; Dolatabadi, H.R.D.; Reisi, P. Erythropoietin improves neuronal proliferation in dentate gyrus of hippocampal formation in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2012, 1, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leconte, C.; Bihel, E.; Lepelletier, F.-X.; Bouët, V.; Saulnier, R.; Petit, E.; Boulouard, M.; Bernaudin, M.; Schumann-Bard, P. Comparison of the effects of erythropoietin and its carbamylated derivative on behaviour and hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Neuropharmacology 2011, 60, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shingo, T.; Sorokan, S.T.; Shimazaki, T.; Weiss, S. Erythropoietin regulates the in vitro and in vivo production of neuronal progenitors by mammalian forebrain neural stem cells. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 9733–9743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakhloo, D.; Scharkowski, F.; Curto, Y.; Butt, U.J.; Bansal, V.; Steixner-Kumar, A.A.; Wüstefeld, L.; Rajput, A.; Arinrad, S.; Zillmann, M.R.; et al. Functional hypoxia drives neuroplasticity and neurogenesis via brain erythropoietin. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, R.R.; Kraemer, B.R. The effects of peripheral hormone responses to exercise on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1202349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praag, H.v.; Christie, B.R.; Sejnowski, T.J.; Gage, F.H. Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13427–13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.P.; Fried, P.J.; Macone, J.; Stillman, A.; Gomes-Osman, J.; Costa-Miserachs, D.; Muñoz, J.M.T.; Santarnecchi, E.; Pascual-Leone, A. Light Aerobic Exercise Modulates Executive Function and Cortical Excitability. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 51, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tour, S.L.; Shaikh, H.; Beardwood, J.H.; Augustynski, A.S.; Wood, M.A.; Keiser, A.A. The weekend warrior effect: Consistent intermittent exercise induces persistent cognitive benefits. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2024, 214, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, T.; Giladi, N.; Hendler, T.; Havakuk, O.; Lerner, Y. Physically Active Lifestyle Is Associated With Attenuation of Hippocampal Dysfunction in Cognitively Intact Older Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 720990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, K.I.; Voss, M.W.; Prakash, R.S.; Basak, C.; Szabo, A.; Chaddock, L.; Kim, J.S.; Heo, S.; Alves, H.; White, S.M.; et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3017–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, M.W.; Erickson, K.I.; Prakash, R.S.; Chaddock, L.; Kim, J.S.; Alves, H.; Szabo, A.; Phillips, S.M.; Wójcicki, T.R.; Mailey, E.L.; et al. Neurobiological markers of exercise-related brain plasticity in older adults. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 28, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotman, C.W.; Berchtold, N.C.; Christie, L.-A. Exercise builds brain health: Key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2007, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempin, F.; Beis, D.; Mosienko, V.; Kempermann, G.; Bader, M.; Alenina, N. Serotonin is required for exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 8270–8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Tian, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, B. Aerobic Exercise Restores Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Cognitive Function by Decreasing Microglia Inflammasome Formation Through Irisin/NLRP3 Pathway. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Valaris, S.; Young, M.F.; Haley, E.B.; Luo, R.; Bond, S.F.; Mazuera, S.; Kitchen, R.R.; Caldarone, B.J.; Bettio, L.E.B.; et al. Exercise hormone irisin is a critical regulator of cognitive function. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 1058–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, S.Y.; Li, A.; Xu, A.; So, K.-F. Fat cell-secreted adiponectin mediates physical exercise-induced hippocampal neurogenesis: An alternative anti-depressive treatment? Neural Regen. Res. 2015, 10, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.A.; Blackmore, D.G.; Zhuo, J.; Nasrallah, F.A.; To, X.; Kurniawan, N.D.; Carlisle, A.; Vien, K.-Y.; Chuang, K.-H.; Jiang, T.; et al. Neurogenic-dependent changes in hippocampal circuitry underlie the procognitive effect of exercise in aging mice. iScience 2021, 24, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aztiria, E.; Capodieci, G.; Arancio, L.; Leanza, G. Extensive training in a maze task reduces neurogenesis in the adult rat dentate gyrus probably as a result of stress. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 416, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, T.; Kawakami, M.; Kita, I. Long-Term Exercise Is a Potent Trigger for ΔFosB Induction in the Hippocampus along the dorso–ventral Axis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, L.; Ma, L.; Liu, F.; Cui, S.; Cai, J.; Liao, F.; Wan, Y.; Yi, M. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis along the Dorsoventral Axis Contributes Differentially to Environmental Enrichment Combined with Voluntary Exercise in Alleviating Chronic Inflammatory Pain in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 4145–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Reddy, V.; Shumway, K.R.; Araujo, J.F. Physiology, Sleep Stages. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526132/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Diekelmann, S.; Born, J.; Diekelmann, S.; Born, J. The memory function of sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, A.J.; Simon, E.B.; Mander, B.A.; Greer, S.M.; Saletin, J.M.; Goldstein-Piekarski, A.N.; Walker, M.P.; Krause, A.J.; Simon, E.B.; Mander, B.A.; et al. The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, M.L.; Giles, D.E.; Buysse, D.J.; Tu, X.; Kupfer, D.J. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1997, 42, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerlo, P.; Mistlberger, R.; Jacobs, B.; Heller, H.; McGinty, D. New neurons in the adult brain: The role of sleep and consequences of sleep loss. Sleep Med. Rev. 2009, 13, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, Y.; Oka, A.; Iseki, A.; Mori, M.; Ohe, K.; Mine, K.; Enjoji, M. Prolonged sleep deprivation decreases cell proliferation and immature newborn neurons in both dorsal and ventral hippocampus of male rats. Neurosci. Res. 2018, 131, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirescu, C.; Peters, J.D.; Noiman, L.; Gould, E. Sleep deprivation inhibits adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus by elevating glucocorticoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19170–19175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.; Rocha, N.B.F.; Rocha, S.; Herrera-Solís, A.; Salas-Pacheco, J.; García-García, F.; Murillo-Rodríguez, E.; Yuan, T.-F.; Machado, S.; Arias-Carrión, O. Detrimental role of prolonged sleep deprivation on adult neurogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Rodriguez, S.; Lopez-Armas, G.; Luquin, S.; Ramos-Zuñiga, R.; Jauregui-Huerta, F.; Gonzalez-Perez, O.; Gonzalez-Castañeda, R.E. Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Deprivation Produces Long-Term Detrimental Effects in Spatial Memory and Modifies the Cellular Composition of the Subgranular Zone. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanti, A.; Belzung, C. Neurogenesis along the septo-temporal axis of the hippocampus: Are depression and the action of antidepressants region-specific? Neuroscience 2013, 252, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, T.D.; Dwork, A.J.; Keegan, K.A.; Thirumangalakudi, L.; Lipira, C.M.; Joyce, N.; Lange, C.; Higley, J.D.; Rosoklija, G.; Hen, R.; et al. Necessity of hippocampal neurogenesis for the therapeutic action of antidepressants in adult nonhuman primates. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shors, T.J.; Miesegaes, G.; Beylin, A.; Zhao, M.; Rydel, T.; Gould, E. Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature 2001, 410, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rabaza, V.; Llorens-Martín, M.; Velázquez-Sánchez, C.; Ferragud, A.; Arcusa, A.; Gumus, H.G.; Gómez-Pinedo, U.; Pérez-Villalba, A.; Roselló, J.; Trejo, J.L.; et al. Inhibition of adult hippocampal neurogenesis disrupts contextual learning but spares spatial working memory, long-term conditional rule retention and spatial reversal. Neuroscience 2009, 159, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, G.; Wojtowicz, J.M.; Sekeres, M.; Snyder, J.S.; Wang, S. Inhibition of neurogenesis interferes with hippocampus-dependent memory function. Hippocampus 2006, 16, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shors, T.J. Saving new brain cells. Sci. Am. 2009, 300, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shors, T.J. From Stem Cells to Grandmother Cells: How Neurogenesis Relates to Learning and Memory. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 3, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel M Curlik, I.; Shors, T.J. Learning Increases the Survival of Newborn Neurons Provided That Learning Is Difficult to Achieve and Successful. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010, 23, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, H.M.; Glass, A.L.; Shors, T.J. Neurogenesis and the spacing effect: Learning over time enhances memory and the survival of new neurons. Learn. Mem. 2007, 14, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdugo-Vega, G.; Lee, C.-C.; Garthe, A.; Kempermann, G.; Calegari, F. Adult-born neurons promote cognitive flexibility by improving memory precision and indexing. Hippocampus 2021, 31, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguire, E.A.; Woollett, K.; Spiers, H.J. London taxi drivers and bus drivers: A structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus 2006, 16, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollett, K.; Maguire, E.A. Acquiring “the Knowledge” of London’s layout drives structural brain changes. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 2109–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Verma, A.; Jha, S.K. Training on an Appetitive Trace-Conditioning Task Increases Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis and the Expression of Arc, Erk and CREB Proteins in the Dorsal Hippocampus. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seib, D.R.; Espinueva, D.F.; Princz-Lebel, O.; Chahley, E.; Stevenson, J.; O’Leary, T.P.; Floresco, S.B.; Snyder, J.S. Hippocampal neurogenesis promotes preference for future rewards. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6317–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacker, C.; Luna, V.M.; Stevens, G.S.; Millette, A.; Shores, R.; Jimenez, J.C.; Chen, B.; Hen, R. Hippocampal neurogenesis confers stress resilience by inhibiting the ventral dentate gyrus. Nature 2018, 559, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabenhorst, F.; Rolls, E.T. Value, pleasure and choice in the ventral prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.Y.; Haesler, S.; Vong, L.; Lowell, B.B.; Uchida, N. Neuron-type-specific signals for reward and punishment in the ventral tegmental area. Nature 2012, 482, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speranza, L.; Porzio, U.d.; Viggiano, D.; Donato, A.d.; Volpicelli, F. Dopamine: The Neuromodulator of Long-Term Synaptic Plasticity, Reward and Movement Control. Cells 2021, 10, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komisaruk, B.R.; Cerro, M.C.R.d. How Does Our Brain Generate Sexual Pleasure? Int. J. Sex. Health 2021, 33, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuner, B.; Glasper, E.R.; Gould, E. Sexual Experience Promotes Adult Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus Despite an Initial Elevation in Stress Hormones. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasper, E.R.; Gould, E. Sexual experience restores age-related decline in adult neurogenesis and hippocampal function. Hippocampus 2013, 23, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura, N.; Nakagawa, S.; Masuda, T.; Boku, S.; Kato, A.; Song, N.; An, Y.; Kitaichi, Y.; Inoue, T.; Koyama, T.; et al. The effect of dopamine on adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 50, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, R.; Steigleder, T.; Schlachetzki, J.C.M.; Waldmann, E.; Schwab, S.; Winner, B.; Winkler, J.; Kohl, Z. Distinct Effects of Chronic Dopaminergic Stimulation on Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Striatal Doublecortin Expression in Adult Mice. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.M.; Hotsenpiller, G.; Peterson, D.A. Acute Psychosocial Stress Reduces Cell Survival in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis without Altering Proliferation. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2734–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Czéh, B.; Fuchs, E. Age-dependent susceptibility of adult hippocampal cell proliferation to chronic psychosocial stress. Brain Res. 2005, 1049, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, D.F.; Leasure, J.L. Region-specific response of the hippocampus to chronic unpredictable stress. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preez, A.D.; Onorato, D.; Eiben, I.; Musaelyan, K.; Egeland, M.; Zunszain, P.A.; Fernandes, C.; Thuret, S.; Pariante, C.M. Chronic stress followed by social isolation promotes depressive-like behaviour, alters microglial and astrocyte biology and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis in male mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 91, 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, R.; Roque, A.; Pineda, E.; Licona-Limón, P.; Valdéz-Alarcón, J.J.; Lajud, N. Early life stress accelerates age-induced effects on neurogenesis, depression, and metabolic risk. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 96, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirescu, C.; Gould, E. Stress and adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus 2006, 16, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, L.W.; Polotsky, A.J. Can we live longer by eating less? A review of caloric restriction and longevity. Maturitas 2012, 71, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Duan, W.; Long, J.M.; Ingram, D.K.; Mattson, M.P.; Lee, J.; Duan, W.; Long, J.M.; Ingram, D.K.; Mattson, M.P. Dietary restriction increases the number of newly generated neural cells, and induces BDNF expression, in the dentate gyrus of rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2000, 15, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.; Sato, T.; Kojima, M.; Park, S. Ghrelin is required for dietary restriction-induced enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis: Lessons from ghrelin knockout mice. Endocr. J. 2015, 62, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, Z.; Akgün-Dar, K.; Kapucu, A.; Dedeakayoğulları, H.; Batu, Ş.; Üzüm, G. Long term consequences on spatial learning-memory of low-calorie diet during adolescence in female rats; hippocampal and prefrontal cortex BDNF level, expression of NeuN and cell proliferation in dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 2015, 1618, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Marrana, F.; Andrade, J.P. Caloric restriction in young rats disturbs hippocampal neurogenesis and spatial learning. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 133, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, S.; Okaichi, H.; Sugioka, K. Dietary restriction inhibits spatial learning ability and hippocampal cell proliferation in rats. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2008, 50, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, M.C.; Fannon-Pavlich, M.J.; Mysore, K.K.; Dutta, R.R.; Ongjoco, A.T.; Quach, L.W.; Kharidia, K.M.; Somkuwar, S.S.; Mandyam, C.D. Dietary Restriction reduces hippocampal neurogenesis and granule cell neuron density without affecting the density of mossy fibers. Brain Res. 2017, 1663, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A.; Bienias, J.L.; Tangney, C.C.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.; Schneider, J.; Wilson, R.S. Dietary Fats and the Risk of Incident Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, C.E.; Winocur, G. Cognitive impairment in rats fed high-fat diets: A specific effect of saturated fatty-acid intake. Behav. Neurosci. 1996, 110, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, C.E.; Winocur, G. Learning and memory impairment in rats fed a high saturated fat diet. Behav. Neural Biol. 1990, 53, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, S.; Launer, L.J.; Ott, A.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M.B. Dietary fat intake and the risk of incident dementia in the Rotterdam study. Ann. Neurol. 1997, 42, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, A.; Mohapel, P.; Bouter, B.; Frielingsdorf, H.; Pizzo, D.; Brundin, P.; Erlanson-Albertsson, C. High-fat diet impairs hippocampal neurogenesis in male rats. Eur. J. Neurol. 2006, 13, 1385–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, J.; Kang, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Pu, T.; et al. High-Fat Diet Consumption in Adolescence Induces Emotional Behavior Alterations and Hippocampal Neurogenesis Deficits Accompanied by Excessive Microglial Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granholm, A.-C.; Bimonte-Nelson, H.A.; Moore, A.B.; Nelson, M.E.; Freeman, L.R.; Sambamurti, K. Effects of a Saturated Fat and High Cholesterol Diet on Memory and Hippocampal Morphology in the Middle-Aged Rat. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008, 14, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.R.; Haley-Zitlin, V.; Rosenberger, D.S.; Granholm, A.-C. Damaging effects of a high-fat diet to the brain and cognition: A review of proposed mechanisms. Nutr. Neurosci. 2013, 17, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Y.I.; Viriyakosol, S.; Binder, C.J.; Feramisco, J.R.; Kirkland, T.N.; Witztum, J.L. Minimally modified LDL binds to CD14, induces macrophage spreading via TLR4/MD-2, and inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, C.P.; Laxton, R.C.; Patel, K.; Ye, S. Advanced glycation end-product of low density lipoprotein activates the toll-like 4 receptor pathway implications for diabetic atherosclerosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Y.I. Toll-like Receptors and Atherosclerosis: Oxidized Ldl As an Endogenous Toll-like Receptor Ligand. Future Cardiol. 2005, 1, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.G.; Yost, O.L.; Potter, O.V.; Giedraitis, M.E.; Kohman, R.A. Toll-like receptor 4 differentially regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis in an age- and sex-dependent manner. Hippocampus 2020, 30, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Gobinath, A.R.; Wen, Y.; Austin, J.; Galea, L.A.M. Folic acid, but not folate, regulates different stages of neurogenesis in the ventral hippocampus of adult female rats. J. Neuroendocr. 2019, 31, e12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Zhong, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, N.; Zhou, G.; Xu, T.; Hong, Z. Impaired hippocampal neurogenesis is involved in cognitive dysfunction induced by thiamine deficiency at early pre-pathological lesion stage. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008, 29, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, J.R.; Ferguson, M.A.; Anderson, C.A.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Gilboa, A.; Berman, B.D.; Fox, M.D. Network Localization of Spontaneous Confabulation. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 36, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, E.; Touyarot, K.; Alfos, S.; Pallet, V.; Higueret, P.; Abrous, D.N. Retinoic Acid Restores Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Reverses Spatial Memory Deficit in Vitamin A Deprived Rats. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, J.; Sakai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Koul, O.; Mineur, Y.; Crusio, W.E.; McCaffery, P.; Crandall, J.; Sakai, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. 13-cis-retinoic acid suppresses hippocampal cell division and hippocampal-dependent learning in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.M.; Seo, M.; Seo, J.-S.; Rhim, H.; Nahm, S.-S.; Cho, I.-H.; Chang, B.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Choi, S.-H.; Nah, S.-Y.; et al. Ascorbic Acid Mitigates D-galactose-Induced Brain Aging by Increasing Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Improving Memory Function. Nutrients 2019, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveden-Nyborg, P.; Johansen, L.K.; Raida, Z.; Villumsen, C.K.; Larsen, J.O.; Lykkesfeldt, J. Vitamin C deficiency in early postnatal life impairs spatial memory and reduces the number of hippocampal neurons in guinea pigs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, K.; Jara, N.; Ramírez, E.; Lima, I.d.; Smith-Ghigliotto, J.; Muñoz, V.; Ferrada, L.; Nualart, F. Role of vitamin C and SVCT2 in neurogenesis. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 1, 11557587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corniola, R.S.; Tassabehji, N.M.; Hare, J.; Sharma, G.; Levenson, C.W. Zinc deficiency impairs neuronal precursor cell proliferation and induces apoptosis via p53-mediated mechanisms. Brain Res. 2008, 1237, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshpour, A.; Leite, M.E.N.; Wagner, K.-H.; Sabico, S.; Al-Daghri, N.M.; Aldisi, D.; König, D.; Gil, J.F.L.; Stubbs, B. Selenium and brain aging: A comprehensive review with a focus on hippocampal neurogenesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 112, 102898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakita, E.; Hashimoto, M.; Shido, O. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Neuroscience 2006, 139, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, S.C.; Michael, G.J.; Michael-Titus, A.T. Omega-3 fatty acids reverse age-related decreases in nuclear receptors and increase neurogenesis in old rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Medoro, A.; Ali, S.; Passarella, D.; Intrieri, M.; Scapagnini, G. Dietary Flavonoids and Adult Neurogenesis: Potential Implications for Brain Aging. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Son, T.G.; Park, H.R.; Park, M.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, H.Y.; Mattson, M.P.; Lee, J. Curcumin Stimulates Proliferation of Embryonic Neural Progenitor Cells and Neurogenesis in the Adult Hippocampus. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 14497–14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, S.; Gong, D.; Yang, M.; Qiu, Q.; Luo, J.; Chen, T. Curcumin Improves Neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice via the Upregulation of Wnt/β-Catenin and BDNF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannerman, D.; Sprengel, R.; Sanderson, D.; McHugh, S.; Rawlins, J.; Monyer, H.; Seeburg, P. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity, spatial memory and anxiety. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, B.A.; Witter, M.P.; Lein, E.S.; Moser, E.I. Functional organization of the hippocampal longitudinal axis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanselow, M.S.; Dong, H.-W. Are The Dorsal and Ventral Hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron 2010, 65, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.L.; Pathak, S.D.; Jeromin, A.; Ng, L.L.; MacPherson, C.R.; Mortrud, M.T.; Cusick, A.; Riley, Z.L.; Sunkin, S.M.; Bernard, A.; et al. Genomic anatomy of the hippocampus. Neuron 2008, 60, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodoropoulos, C. Electrophysiological evidence for long-axis intrinsic diversification of the hippocampus. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 109–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J.S.; Choe, J.S.; Clifford, M.A.; Jeurling, S.I.; Hurley, P.; Brown, A.; Kamhi, J.F.; Cameron, H.A. Adult-Born Hippocampal Neurons Are More Numerous, Faster Maturing, and More Involved in Behavior in Rats than in Mice. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 14484–14495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrein, I. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in natural populations of mammals. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a021295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, O.; O’Connor, R.; Cryan, J. Lithium-induced effects on adult hippocampal neurogenesis are topographically segregated along the dorso-ventral axis of stressed mice. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberta Gioia, T.S.; Diamanti, T.; Fimmanò, S.; Vitale, M.; Ahlenius, H.; Kokaia, Z.; Tirone, F.; Micheli, L.; Biagioni, S.; Lupo, G.; et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and social behavioural deficits in the R451C Neuroligin3 mouse model of autism are reverted by the antidepressant fluoxetine. J. Neurochem. 2023, 165, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Ko, H.; Sun, T.; Kim, S. Distinct function of miR-17-92 cluster in the dorsal and ventral adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 1594–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, I.; Tan, S.; Davoli, M.; Dominguez-Lopez, S.; Qiang, C.; Rachalski, A.; Turecki, G.; Mechawar, N. Subchronic peripheral neuregulin-1 increases ventral hippocampal neurogenesis and induces antidepressant-like effects. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotto, V.; Bondi, H.; Cuccurazzu, B.; Rinaldi, M.; Canonico, P.; Grilli, M. Salmeterol, a β2 Adrenergic Agonist, Promotes Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in a Region-Specific Manner. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.; Marchisella, F.; Ortega-Martinez, S.; Hollos, P.; Eerola, K.; Komulainen, E.; Kulesskaya, N.; Freemantle, E.; Fagerholm, V.; Savontaus, E.; et al. JNK1 controls adult hippocampal neurogenesis and imposes cell-autonomous control of anxiety behaviour from the neurogenic niche. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus-Pinheiro, A.; Alves, N.D.; Patrício, P.; Machado-Santos, A.R.; Loureiro-Campos, E.; Silva, J.M.; Sardinha, V.M.; Reis, J.; Schorle, H.; Oliveira, J.F.; et al. AP2γ controls adult hippocampal neurogenesis and modulates cognitive, but not anxiety or depressive-like behavior. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Kim, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Seo, J.; Kim, Y.; Sun, T. miR-17-92 Cluster Regulates Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis, Anxiety, and Depression. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Bonaguidi, M.; Jun, H.; Guo, J.; Sun, G.; Will, B.; Yang, Z.; Jang, M.; Song, H.; Ming, G.; et al. A septo-temporal molecular gradient of sfrp3 in the dentate gyrus differentially regulates quiescent adult hippocampal neural stem cell activation. Mol. Brain 2015, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Bonaguidi, M.; Kitabatake, Y.; Sun, J.; Song, J.; Kang, E.; Jun, H.; Zhong, C.; Su, Y.; Guo, J.; et al. Secreted frizzled-related protein 3 regulates activity-dependent adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.A.; Bond, A.M.; Ming, G.-L.; Song, H. Radial glial cells in the adult dentate gyrus: What are they and where do they come from? F1000Research 2018, 7, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Jin, N.; Guo, W. Neural stem cell heterogeneity in adult hippocampus. Cell Regen. 2025, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Dhaliwal, J.S.; Ceizar, M.; Vaculik, M.; Kumar, K.L.; Lagace, D.C. Knockout of Atg5 delays the maturation and reduces the survival of adult-generated neurons in the hippocampus. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayach, A.; Wang, C. Autophagy in neural stem cells and glia for brain health and diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckleberry, K.; Shue, F.; Copeland, T.; Chitwood, R.; Yin, W.; Drew, M. Dorsal and ventral hippocampal adult-born neurons contribute to context fear memory. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 2487–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritger, A.C.; Parker, R.K.; Trask, S.; Ferrara, N.C. Elevated fear states facilitate ventral hippocampal engagement of basolateral amygdala neuronal activity. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1347525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.N.; Hamou, N.; Wiener, S.I. Integration of fear learning and fear expression across the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, C.I.; Galvão, B.d.O.; Maisonette, S.; Landeira-Fernandez, J. Effect of Dorsal and Ventral Hippocampal Lesions on Contextual Fear Conditioning and Unconditioned Defensive Behavior Induced by Electrical Stimulation of the Dorsal Periaqueductal Gray. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e83342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van-Dijk, R.; Wiget, F.; Wolfer, D.; Slomianka, L.; Amrein, I. Consistent within-group covariance of septal and temporal hippocampal neurogenesis with behavioral phenotypes for exploration and memory retention across wild and laboratory small rodents. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 372, 112034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, D.F.; Morch, K.; Christie, B.R.; Leasure, J.L. Differential response of hippocampal subregions to stress and learning. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetreno, R.; Klintsova, A.; Savage, L. Stage-dependent alterations of progenitor cell proliferation and neurogenesis in an animal model of Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Brain Res. 2011, 1391, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Valadez, B.; Gallardo-Caballero, M.; Llorens-Martín, M. Human adult hippocampal neurogenesis is shaped by neuropsychiatric disorders, demographics, and lifestyle-related factors. Cell Stem Cell 2025, 32, 1577–1594.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, W.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Solmi, M.; Furukawa, T.A.; Firth, J.; Carvalho, A.F.; Berk, M. Major depressive disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.F.; Peng, W.; Sweeney, J.A.; Jia, Z.Y.; Gong, Q.Y. Brain structure alterations in depression: Psychoradiological evidence. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2018, 24, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, M.C.; Yucel, K.; Nazarov, A.; MacQueen, G.M. A meta-analysis examining clinical predictors of hippocampal volume in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009, 34, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.L.; van Praag, H.; Gage, F.H.; Jacobs, B.L.; van Praag, H.; Gage, F.H. Adult brain neurogenesis and psychiatry: A novel theory of depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2000, 5, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberg, J.E.; Eisch, A.J.; Nestler, E.J.; Duman, R.S. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 9104–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, M.; Santiago, A.N.; Hen, R.; Dwork, A.J.; Rosoklija, G.B.; Tamir, H.; Arango, V.; John Mann, J. Hippocampal Granule Neuron Number and Dentate Gyrus Volume in Antidepressant-Treated and Untreated Major Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, M.; Underwood, M.D.; Hen, R.; Rosoklija, G.B.; Dwork, A.J.; John Mann, J.; Arango, V. Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 2376–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.; Silveira-Rosa, T.; Martins-Macedo, J.; Marques-Ferraz, L.; Dourado, A.R.; Martins-Ferreira, G.; Farrugia, F.; Rodrigues, A.J.; Abrous, D.N.; Alves, N.D.; et al. Chronic stress and cytogenesis ablation disrupt hippocampal neuron connectivity, with fluoxetine restoring function with sex-specific effects. Neurobiol. Stress. 2025, 37, 100743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surget, A.; Saxe, M.; Leman, S.; Ibarguen-Vargas, Y.; Chalon, S.; Griebel, G.; Hen, R.; Belzung, C. Drug-Dependent Requirement of Hippocampal Neurogenesis in a Model of Depression and of Antidepressant Reversal. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 64, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarelli, L.; Saxe, M.; Gross, C.; Surget, A.; Battaglia, F.; Dulawa, S.; Weisstaub, N.; Lee, J.; Duman, R.; Arancio, O.; et al. Requirement of Hippocampal Neurogenesis for the Behavioral Effects of Antidepressants. Science 2003, 301, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banasr, M.; Soumier, A.; Hery, M.; Mocaër, E.; Daszuta, A. Agomelatine, a new antidepressant, induces regional changes in hippocampal neurogenesis. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanti, A.; Westphal, W.; Girault, V.; Brizard, B.; Devers, S.; Leguisquet, A.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C. Region-dependent and stage-specific effects of stress, environmental enrichment, and antidepressant treatment on hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus 2013, 23, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.-G.; Lee, D.; Ro, E.J.; Suh, H. Regional-specific effect of fluoxetine on rapidly dividing progenitors along the dorsoventral axis of the hippocampus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.-J.; Xu, N.; Kong, L.; Sun, S.-C.; Xu, X.-F.; Jia, M.-Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.-Y. The antidepressant roles of Wnt2 and Wnt3 in stress-induced depression-like behaviors. Transl. Psychiatry 2016, 6, e892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szapacs, M.E.; Mathews, T.A.; Tessarollo, L.; Lyons, W.E.; Mamounas, L.A.; Andrews, A.M. Exploring the relationship between serotonin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor: Analysis of BDNF protein and extraneuronal 5-HT in mice with reduced serotonin transporter or BDNF expression. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 140, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leschik, J.; Gentile, A.; Cicek, C.; Péron, S.; Tevosian, M.; Beer, A.; Radyushkin, K.; Bludau, A.; Ebner, K.; Neumann, I.; et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in serotonergic neurons improves stress resilience and promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 217, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Wen, Z.; Song, H.; Christian, K.M.; Ming, G.-L. Adult Neurogenesis and Psychiatric Disorders. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a019026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, D.J.; Kirwan, C.B. A possible negative influence of depression on the ability to overcome memory interference. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 256, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airan, R.D.; Meltzer, L.A.; Roy, M.; Gong, Y.; Chen, H.; Deisseroth, K. High-speed imaging reveals neurophysiological links to behavior in an animal model of depression. Science 2007, 317, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hany, M.; Rizvi, A. Schizophrenia. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539864/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Kuo, S.S.; Pogue-Geile, M.F. Variation in Fourteen Brain Structure Volumes in Schizophrenia: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of 246 Studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 98, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, A.; Fritzen, S.; Finger, M.; Strobel, A.; Lauer, M.; Schmitt, A.; Lesch, K. Neural stem cell proliferation is decreased in schizophrenia, but not in depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2006, 11, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissleder, C.; North, H.F.; Bitar, M.; Fullerton, J.M.; Sager, R.; Barry, G.; Piper, M.; Halliday, G.M.; Webster, M.J.; Shannon Weickert, C. Reduced adult neurogenesis is associated with increased macrophages in the subependymal zone in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 6880–6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajebhosale, P.; Jone, A.; Johnson, K.R.; Hofland, R.; Palarpalar, C.; Khan, S.; Role, L.W.; Talmage, D.A. Neuregulin1 Nuclear Signaling Influences Adult Neurogenesis and Regulates a Schizophrenia Susceptibility Gene Network within the Mouse Dentate Gyrus. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e0063242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandilakis, C.L.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Serotonin Modulation of Dorsoventral Hippocampus in Physiology and Schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, A.A. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sidhu, J.; Lui, F.; Tsao, J.W. Alzheimer Disease. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499922/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Ávila-Villanueva, M.; Dolado, A.M.; Gómez-Ramírez, J.; Fernández-Blázquez, M. Brain Structural and Functional Changes in Cognitive Impairment Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 886619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzmann, R.A.; Schnitzlein, H.N.; Murtagh, F.R. An english translation of alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “über eine eigenartige erkankung der hirnrinde”. Clin. Anat. 1995, 8, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, B.S.; Butters, M.A.; Albert, S.M.; Dew, M.A.; Reynolds, C.F. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Jiménez, E.; Terreros-Roncal, J.; Flor-García, M.; Rábano, A.; Llorens-Martín, M. Evidences for Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Humans. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 2541–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y.; Gurland, B.; Tatemichi, T.K.; Tang, M.X.; Wilder, D.; Mayeux, R. Influence of Education and Occupation on the Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease. JAMA 1994, 271, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disouky, A.; Lazarov, O. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 177, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, M.; Chida, Y. Physical activity and risk of neurodegenerative disease: A systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychol. Med. 2009, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin-Escalera, J.; Leclerc, M.; Calon, F. High-Fat Diets in Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease: How Can Eating Too Much Fat Increase Alzheimer’s Disease Risk? J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 97, 977–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.-N.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, B.; Huang, S.-M. Sleep deficiency promotes Alzheimer’s disease development and progression. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1053942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallensten, J.; Ljunggren, G.; Nager, A.; Wachtler, C.; Bogdanovic, N.; Petrovic, P.; Carlsson, A.C. Stress, depression, and risk of dementia—A cohort study in the total population between 18 and 65 years old in Region Stockholm. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluyau, D.; Hashmi, M.F.; Charlton, T.E. Drug Addiction. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549783/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Uhl, G.R.; Koob, G.F.; Cable, J. The neurobiology of addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1451, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyton, L.; Oliveros, A.; Choi, D.-S.; Jang, M.-H.; Peyton, L.; Oliveros, A.; Choi, D.-S.; Jang, M.-H. Hippocampal regenerative medicine: Neurogenic implications for addiction and mental disorders. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belujon, P.; Grace, A. Dopamine System Dysregulation in Major Depressive Disorders. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.A. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the pathogenesis of addiction and dual diagnosis disorders. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2013, 130, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Uezato, A.; Newell, J.M.; Frazier, E. Major depression and comorbid substance use disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2008, 21, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. Chronic Stress, Drug Use, and Vulnerability to Addiction. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, H.B.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Carpenter, L.; Grzenda, A.; McDonald, W.M.; Rodriguez, C.I.; Kraguljac, N.V. Substance use disorders in schizophrenia: Prevalence, etiology, biomarkers, and treatment. Pers. Med. Psychiatry 2023, 39, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, M.A.; Bulin, S.E.; Fuller, D.C.; Eisch, A.J. Reduction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis confers vulnerability in an animal model of cocaine addiction. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussher, M.H.; Taylor, A.; Faulkner, G. Exercise interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, CD002295.pub3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Abrantes, A.M.; Read, J.P.; Marcus, B.H.; Jakicic, J.; Strong, D.R.; Oakley, J.R.; Ramsey, S.E.; Kahler, C.W.; Stuart, G.; et al. Aerobic Exercise for Alcohol Recovery. Behav. Modif. 2008, 33, 220–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschaux, O.; Vendruscolo, L.F.; Schlosburg, J.E.; Diaz-Aguilar, L.; Yuan, C.J.; Sobieraj, J.C.; George, O.; Koob, G.F.; Mandyam, C.D. Hippocampal neurogenesis protects against cocaine-primed relapse. Addict. Biol. 2014, 19, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Ortega, E.; Santín, L.J. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis as a target for cocaine addiction: A review of recent developments. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 50, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levone, B.R.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Leary, O.F. Role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in stress resilience. Neurobiol. Stress 2015, 1, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planchez, B.; Lagunas, N.; Guisquet, A.-M.L.; Legrand, M.; Surget, A.; Hen, R.; Belzung, C. Increasing Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Promotes Resilience in a Mouse Model of Depression. Cells 2021, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Erginousakis, I.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Modifying Factors of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: A Dorsoventral Perspective in Health and Disease. Cells 2026, 15, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010059

Erginousakis I, Papatheodoropoulos C. Modifying Factors of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: A Dorsoventral Perspective in Health and Disease. Cells. 2026; 15(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleErginousakis, Ioannis, and Costas Papatheodoropoulos. 2026. "Modifying Factors of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: A Dorsoventral Perspective in Health and Disease" Cells 15, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010059

APA StyleErginousakis, I., & Papatheodoropoulos, C. (2026). Modifying Factors of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: A Dorsoventral Perspective in Health and Disease. Cells, 15(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010059