T-Cell-Driven Immunopathology and Fibrotic Remodeling in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Translational Scoping Review

Highlights

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) involves coordinated genetic, epigenetic, and immune remodeling, redefining it as an immunogenetic disorder rather than solely a sarcomeric disease.

- Key molecular drivers and immune cell shifts link RNA regulation, m6A methylation, and inflammatory pathways to myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction.

- Identified diagnostic gene panels and hub genes support transcriptome-based precision diagnostics for HCM.

- Immunometabolic drug targets and integration of biomarkers with imaging may guide personalized immunotherapy and risk stratification.

Abstract

1. Introduction

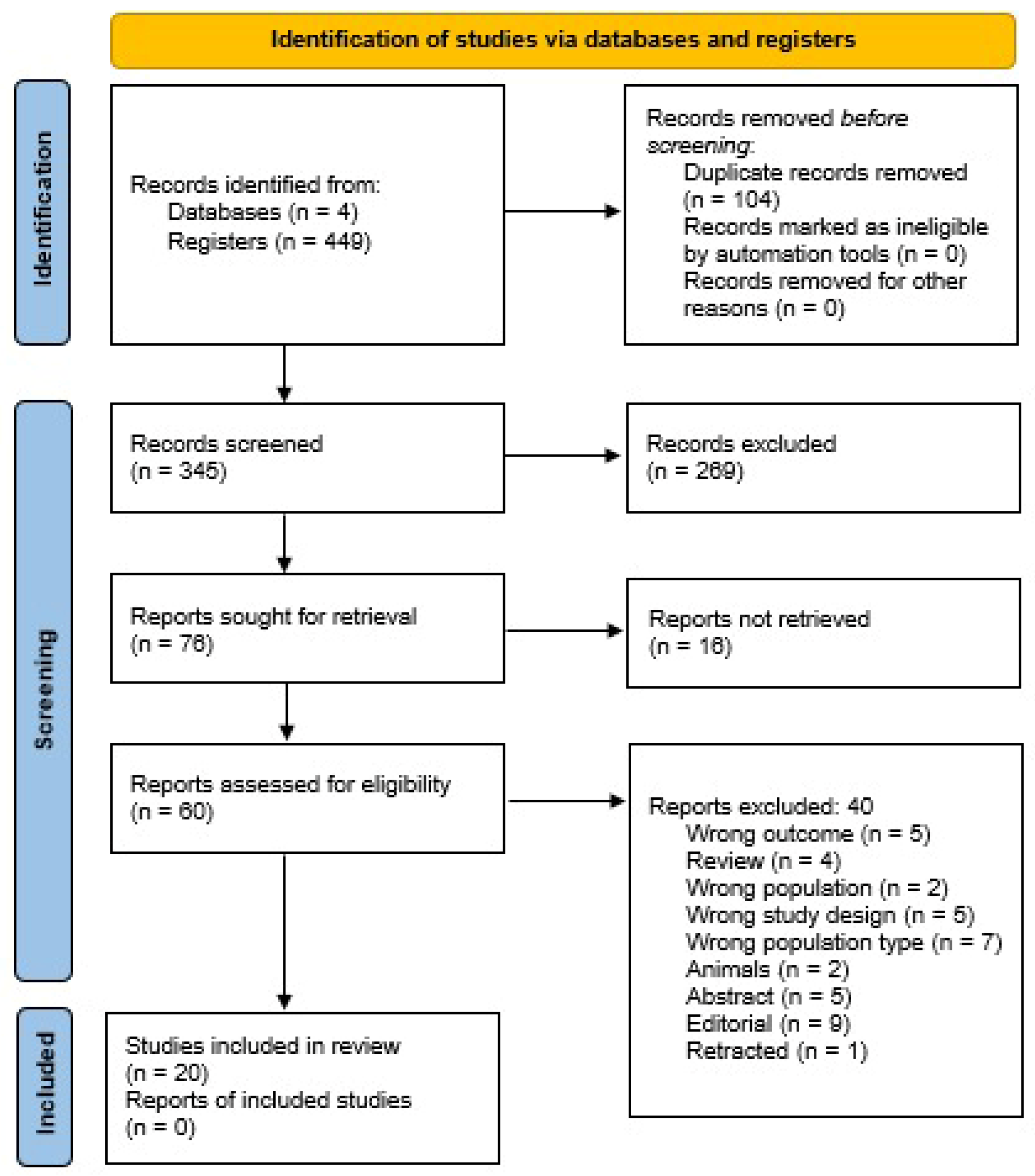

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Human participants diagnosed with HCM confirmed by imaging, histopathology, or genotyping.

- Concept: Evaluation of immune activation, T-cell or macrophage subsets, cytokine expression, RNA modification, or necroptosis mechanisms.

- Context: Investigations using histological, clinical, bioinformatic, transcriptomic, or single-cell approaches.

- Publication characteristics: Peer-reviewed articles published in English.

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

- Bibliographic details (author, year, and country);

- Study design and sample characteristics;

- Assessment modality (immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry, RNA-seq, single-cell profiling, or bioinformatics);

- Key immune or molecular findings (T-cell subsets, macrophage polarization, cytokine pathways, lncRNA–mRNA pairs, m6A readers, and necroptosis genes);

- Clinical correlates (fibrosis, arrhythmia, or outcomes);

- Main conclusions and limitations.

2.5. Critical Appraisal of Evidence

2.6. Data Synthesis and Integration

- Histologic and biopsy-based studies;

- Clinical and biomarker cohorts;

- Transcriptomic and bioinformatic analyses;

- Translational and single-cell investigations.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

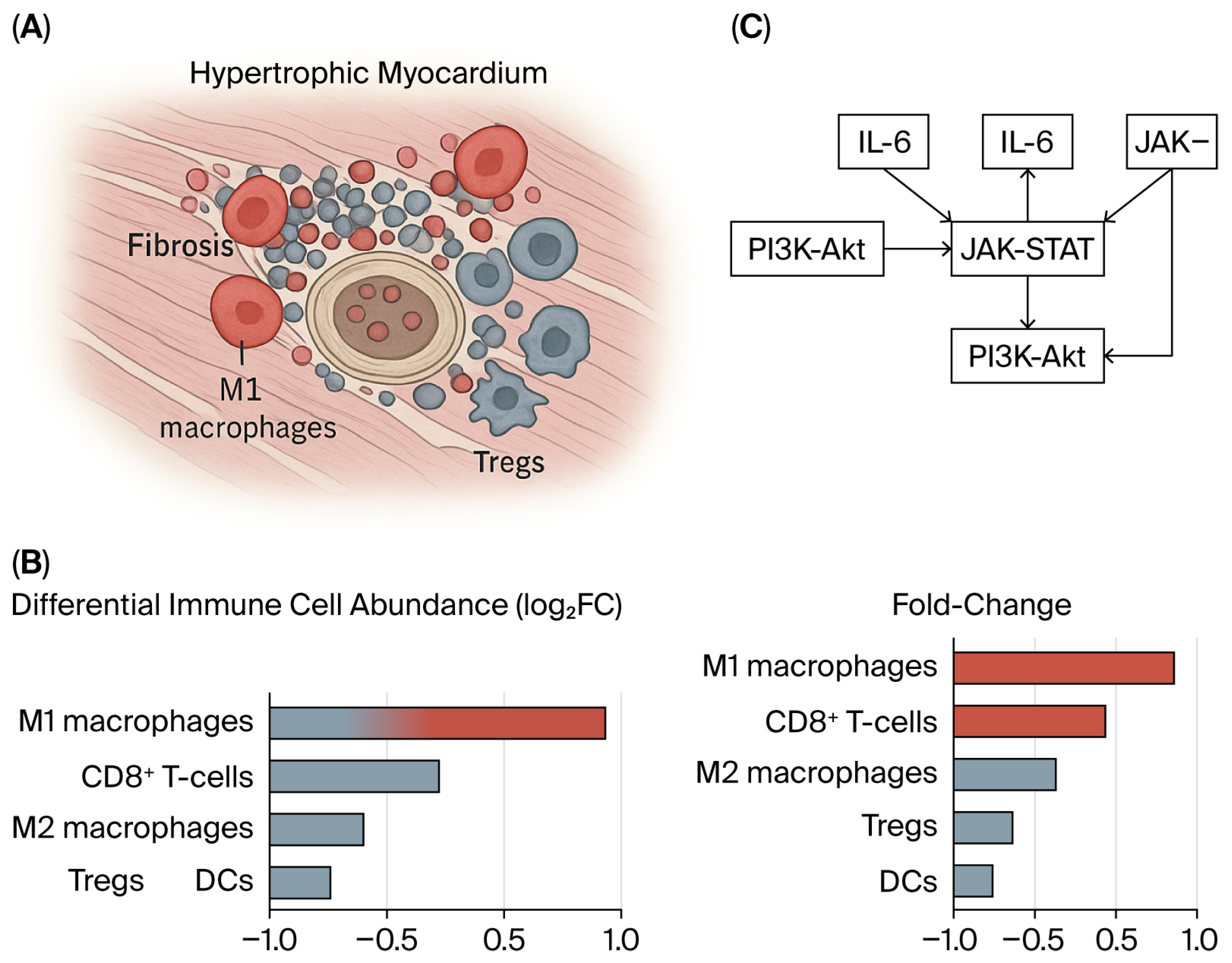

3.1. Immune Dysregulation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

3.2. Immune–Epigenetic Crosstalk and Immune Cell Infiltration in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

3.3. Macrophage Heterogeneity and Remodeling in HCM

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic and Epigenetic Modulators of Immune Remodeling

4.2. Immunoregulation and Cell Infiltration

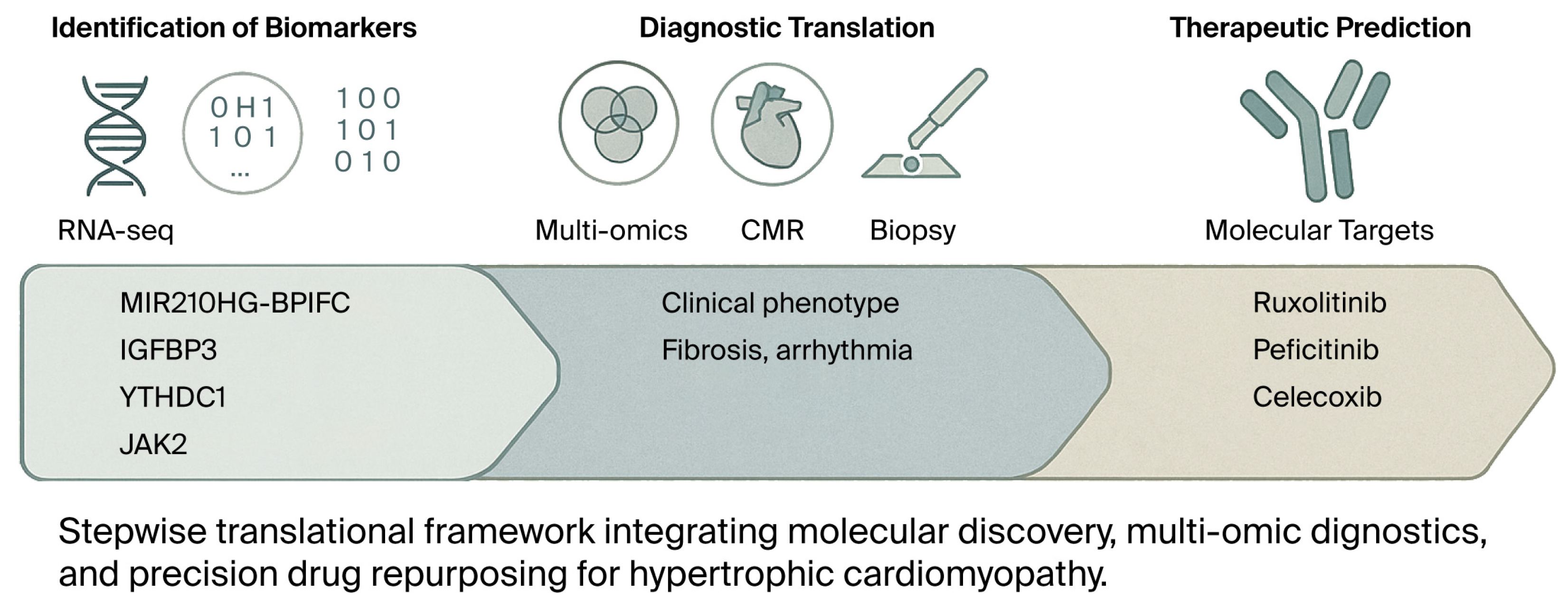

4.3. Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Risk Stratification

4.4. Integrated Model of Ischemia–Immune Interactions Driving Fibrosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

4.5. Therapeutic Targeting and Drug Repurposing

4.6. Targeted Candidates and Rationale (Concise)

4.7. Imaging–Molecular Integration

4.8. Methodological Considerations When Aggregating Public Datasets

4.9. Consolidated Outlook

4.10. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| ALOX5AP | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BPIFC | Bactericidal/permeability-increasing fold-containing family C protein |

| CAF | Collagen area fraction |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| CD14 | Cluster of differentiation 14 |

| CD68 | Cluster of differentiation 68 |

| CD86 | Cluster of differentiation 86 |

| CDC42EP4 | CDC42 effector protein 4 |

| C1QB | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, B chain |

| C1QC | Complement component 1, q subcomponent, C chain |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| CYBB | Cytochrome b-245, beta chain |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FCER1G | Fc fragment of IgE receptor Ig |

| FCN3 | Ficolin-3 |

| FOS | Fos proto-oncogene, AP-1 transcription factor subunit |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HOCM | Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy |

| HCLS1 | Hematopoietic cell-specific Lyn substrate 1 |

| IGFBP3 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| INF-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| ITGB2 | Integrin subunit beta 2 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| JAK-STAT | Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| LGE | Late gadolinium enhancement |

| lncRNA | Long noncoding RNA |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LYVE1 | Lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 |

| M0/M1/M2 | Macrophage phenotypes (naïve/pro-inflammatory/reparative) |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| m6A | N6-methyladenosine |

| ML | Machine learning |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| MYBPC3 | Myosin-binding protein C, cardiac type |

| MYH6 | Myosin heavy chain 6 |

| MYH7 | Myosin heavy chain 7 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NK | Natural killer cell |

| PI3K–Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase–protein kinase B |

| PIK3R1 | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 |

| PLEK | Pleckstrin |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RASD1 | Ras-related dexamethasone-induced 1 |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| ST2 | Suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (IL-33 receptor) |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| Th | T helper |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

| TYROBP | TYRO protein tyrosine kinase-binding protein |

| WGCNA | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis |

| YTHDC1 | YTH domain-containing protein 1 |

References

- Maron, B.J.; Ommen, S.R.; Semsarian, C.; Spirito, P.; Olivotto, I.; Maron, M.S. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Present and future, with translation into contemporary cardiovascular medicine. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 83–99, Erratum in J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Biagini, E.; Blom, N.A.; De Boer, R.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunwald, E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Brief Overview. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 212, S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Day, S.M.; Ashley, E.A.; Michels, M.; Pereira, A.C.; Jacoby, D.; Cirino, A.L.; Fox, J.C.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Ware, J.S.; et al. Genotype and Lifetime Burden of Disease in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Insights from the Sarcomeric Human Cardiomyopathy Registry (SHaRe). Circulation 2018, 138, 1387–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, A.S.; Tang, V.T.; O’Leary, T.S.; Friedline, S.; Wauchope, M.; Arora, A.; Wasserman, A.H.; Smith, E.D.; Lee, L.M.; Wen, X.W.; et al. Effects of MYBPC3 loss-of-function mutations preceding hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 5, e133782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, A.J. Molecular Genetic Basis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1533–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillo, R.; Graziani, F.; Franceschi, F.; Iannaccone, G.; Massetti, M.; Olivotto, I.; Crea, F.; Liuzzo, G. Inflammation across the spectrum of hypertrophic cardiac phenotypes. Heart Fail. Rev. 2023, 28, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, P.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. T cells in cardiac health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e185218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Gao, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Shan, X.; Sun, Y.; Ma, D. Role of Treg cell subsets in cardiovascular disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1331609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Gu, L.; Du, L.; Dong, Z.; Li, Z.; Yu, M.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, H. Identification and analysis of key hypoxia- and immune-related genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amara, M.; Stoler, O.; Birati, E.Y. The Role of Inflammation in the Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Cells 2025, 14, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, B.A.; Sharma, K.; Shah, S.J.; Ho, J.E. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Statement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1810–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Shen, L.; Xu, D. The Role of Regulatory T Cells in Heart Repair After Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2023, 16, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, R.; Meng, Q.; Ma, X.; Shi, S.; Gong, S.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; Gu, W.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; et al. CD4+FoxP3+CD73+ regulatory T cell promotes cardiac healing post-myocardial infarction. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2707–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, R.; Feinberg, M.W. Regulatory T cells in ischemic cardiovascular injury and repair. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020, 147, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boothby, I.C.; Cohen, J.N.; Rosenblum, M.D. Regulatory T cells in skin injury: At the crossroads of tolerance and tissue repair. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eaaz9631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skórka, P.; Piotrowski, J.; Bakinowska, E.; Kiełbowski, K.; Pawlik, A. The Role of Signaling Pathways in Myocardial Fibrosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 27152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nollet, E.E.; Schuldt, M.; Sequeira, V.; Binek, A.; Pham, T.V.; Schoonvelde, S.A.C.; Jansen, M.; Schomakers, B.V.; van Weeghel, M.; Vaz, F.M.; et al. Integrating Clinical Phenotype with Multiomics Analyses of Human Cardiac Tissue Unveils Divergent Metabolic Remodeling in Genotype-Positive and Genotype-Negative Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2024, 17, e004369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Q.; Zhuang, L. Transcriptomic Analyses and Experimental Validation Identified Immune-Related lncRNA-mRNA Pair MIR210HG-BPIFC Regulating the Progression of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Dai, Y.; Chen, K. Identification and verification of IGFBP3 and YTHDC1 as biomarkers associated with immune infiltration and mitophagy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 986995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Fei, S.; Jia, F. Necroptosis and immune infiltration in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Novel insights from bioinformatics analyses. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1293786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z.; Zhang, S.; Tang, T.T.; Cheng, X. Bioinformatics and Immune Infiltration Analyses Reveal the Key Pathway and Immune Cells in the Pathogenesis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 696321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Ud Din, I.; Sadiq, F.M.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; Haris, M.; Mubarak, A.; Farrag, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.; Almekhlafi, S.; Akram, M.; et al. Dysfunctional network of hub genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 8918–8933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Shi, B.; Yang, P.; Khan, A.; Xiong, T.; Li, Z. Unveiling Immune Infiltration Characterizing Genes in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Through Transcriptomics and Bioinformatics. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 3079–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Jin, T.; Liu, M.; Dai, Q. Identification of biomarkers associated with energy metabolism in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and exploration of potential mechanisms of roles. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1546865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Dong, M. Prediction of diagnostic gene biomarkers for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by integrated machine learning. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231213781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, J.; Ding, D.; Fan, M.; Lu, W.; Lu, X.; Yao, L.; Sheng, H. Identification of marker genes associated with oxidative stress in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shintani, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Masaki, A.; Yokoi, M.; Wakami, K.; Ito, T.; Goto, T.; Sugiura, T.; Inagaki, H.; Seo, Y. Clinical impact of the pathological quantification of myocardial fibrosis and infiltrating T lymphocytes using an endomyocardial biopsy in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 362, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, J.; Perera, G.; Batorsky, R.; Wang, H.; Arkun, K.; Chin, M.T. Spatial Transcriptomic Analysis of Focal and Normal Areas of Myocyte Disarray in Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Singh, K.; Lokman, A.B.; Deng, S.; Sunitha, B.; Coelho Lima, J., Jr.; Beglov, J.; Kelly, M.; Blease, A.; Fung, J.C.K.; et al. Regulatory T cells attenuate chronic inflammation and cardiac fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadq3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Pi, Q.; Yang, J.; Wan, M.; Yu, J.; Yang, D.; Guo, Y.; Li, X. A causal association between immune cells and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Genes. Dis. 2025, 12, 101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Ma, W.; Ding, P.; Sun, H.; Guo, X. Interplay of ST2 downregulation and inflammatory dysregulation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathogenesis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1511415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marketou, M.E.; Parthenakis, F.I.; Kalyva, A.; Pontikoglou, C.; Maragkoudakis, S.; Kontaraki, J.E.; Zacharis, E.A.; Patrianakos, A.; Chlouverakis, G.; Papadaki, H.A.; et al. Circulating mesenchymal stem cells in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2015, 24, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, A.S.; Alvarado, F.J.; Yob, J.; Tang, V.T.; Pagani, F.; Russell, M.W.; Valdivia, H.H.; Day, S.M. Genotype-Dependent and -Independent Calcium Signaling Dysregulation in Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2016, 134, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Beale, A.; Ellims, A.H.; Moore, X.L.; Ling, L.H.; Taylor, A.J.; Chin-Dusting, J.; Dart, A.M. Associations between fibrocytes and postcontrast myocardial T1 times in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyva, A.; Marketou, M.E.; Parthenakis, F.I.; Pontikoglou, C.; Kontaraki, J.E.; Maragkoudakis, S.; Petousis, S.; Chlouverakis, G.; Papadaki, H.A.; Vardas, P.E. Endothelial progenitor cells as markers of severity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Yuasa, S.; Mearini, G.; Egashira, T.; Seki, T.; Kodaira, M.; Kusumoto, D.; Kuroda, Y.; Okata, S.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Endothelin-1 induces myofibrillar disarray and contractile vector variability in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Perera, G.; Laird, J.; Batorsky, R.; Maron, M.S.; Rivas, V.N.; Stern, J.A.; Harris, S.; Chin, M.T. Single Cell Transcriptomic Profiling of MYBPC3-Associated Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Across Species Reveals Conservation of Biological Process but Not Gene Expression. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e035780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellims, A.H.; Iles, L.M.; Ling, L.H.; Hare, J.L.; Kaye, D.M.; Taylor, A.J. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy can be identified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and is associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2012, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Xue, Z.K.; Gao, W.; Bai, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.Y.; Li, G. Microcirculatory dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with chest pain assessed by angiography-derived microcirculatory resistance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehan, R.; Yong, A.; Ng, M.; Weaver, J.; Puranik, R. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: A review of recent progress and clinical implications. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1111721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, F.; Cecchi, F.; Olivotto, I.; Camici, P.G. Microvascular Dysfunction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Country/ Setting | Study Design | Population (n) | T-Cell/Marker Evaluated | Evaluation Method | Key Immunologic/ Molecular Findings | Cytokine/Pathway Associations | Fibrosis/Remodeling Evidence | Arrhythmia/ Clinical Outcomes | Level of Evidence/ Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ellims (2012) [42] | Australia: tertiary CMR center | Observational comparative | 51 HCM/25 controls | —(indirect immune readout) | CMR T1 mapping, LGE | ↑ Diffuse interstitial fibrosis correlates with diastolic dysfunction and LA size | Indirect activation of IL-6/JAK-STAT & NF-κB via fibrosis | Fibrosis burden is tightly linked to LVH/ECV | No arrhythmic endpoints (risk inferred) | 3—Imaging fibrosis; no immune phenotyping |

| Fang (2013) [38] | Australia; CMR + cell assays | Prospective observational | 37 HCM/20 controls | Circulating fibrocyte precursors (PBMC → fibrocyte) | Post-contrast T1; fibrocyte culture/flow | Lower T1 (↑ fibrosis) associates with ↑ fibrocyte differentiation; CXCL12 ↑ | CXCL12/SDF-1 chemokine axis; leukocyte trafficking | Fibrocyte activity inversely correlates with T1 (ECM expansion) | Diastolic dysfunction association; no rhythm outcomes | 3—Small; immune readout peripheral |

| Tanaka 2014 [40] | Japan/Germany; academic labs | Translational model | iPSC-CM (3 HCM/3 ctrl); Mybpc3 KI mice | —(ET-1 trigger; myocyte disarray) | iPSC-CM stimulation; motion vector; mouse validation | ET-1 induces hypertrophy/disarray; ETA blockade protective | ET-1/ETA axis; downstream MAPK | Reproduces structural disarray phenotype | Arrhythmogenic substrate inferred by contractile variability | 3—In vitro/model; no patient outcomes |

| Helms 2016 [37] | USA; myectomy tissue | Translational tissue case–control | 25 genotype+/10 genotype−/8 ctrl | CaMKII/PLN signaling (Ca2+ handling) | Protein assays; Ca2+ uptake | CaMKII activation in sarcomere-mutant HCM; SERCA2 ↓ | CaMKII–PLN (pT17); no calcineurin/NFAT | Links Ca2+ mishandling to hypertrophy/ECM | Mechanistic link to arrhythmia substrate; no clinical events | 2–3—Strong tissue mechanistics |

| Kalyva 2016 [39] | Greece; tertiary center | Prospective observational | 40 HCM/23 controls | EPCs (CD45−/CD34+/VEGFR2+, CD133+) | Flow cytometry | ↑ EPCs; correlate with E/e′ (diastolic dysfunction) | VEGF/angiogenesis; endothelial injury | Microvascular dysfunction ↔ fibrosis (indirect) | Not arrhythmia-focused | 3—Immune-vascular axis; modest n |

| Shintani 2022 [31] | Japan, university hospital | Clinical–histological | 34 HCM biopsies | TGF-β1, CTGF, COL1A1, α-SMA (with macrophages) | IHC; RT-PCR | Co-localization of TGF-β1/CTGF with fibrotic areas & macrophage infiltrates | TGF-β/SMAD profibrotic signaling | Fibrosis proportional to TGF-β1 expression | Fibrosis severity associated with ventricular arrhythmia burden | 3—Single center; no causality |

| Wu 2022 [26] | China/Saudi; bioinfo | Cross-sectional bioinformatics | GEO GSE36961 (106 HCM/39 ctrl) | Immune hub genes (CD14, ITGB2, CD163, TYROBP…) | DEG; PPI; ceRNA network | Immune-activation signature implicating leukocyte pathways | Complement/coagulation; NF-κB | ECM organization genes up | No outcomes (diagnostic modeling) | 4—In silico; no wet-lab |

| Li 2022 [23] | China; multi-omics | Bioinformatic + in vitro | GSE36961/130036; H9c2 cells | IGFBP3 (m6A-related), YTHDC1 | RF/LASSO/WGCNA; qPCR | IGFBP3 ↑ (immune-ECM); YTHDC1 → mitophagy (PINK1-PRKN) | TNFα/NF-κB; IL-6–JAK–STAT3 | IGFBP3 overexpression → ↑ COL1A2/COL3A1/MMP9 | No clinical outcomes | 3–4—Cell validation; no tissue outcomes |

| Laird 2023 [32] | USA; myectomy tissue | Spatial transcriptomics | HCM n = 4/donor n = 2 | Region-specific immune/ECM programs | GeoMx panel; snRNA-seq | Severe disarray regions: ↑ mitochondrial/ECM; ↓ interferon signaling | PDGF, fibronectin, CD99, and APP networks | ↑ Fibroblast/vascular composition in disarray | Not powered for outcomes | 3—High-res, small n |

| You & Dong 2023 [29] | China; ML-bioinfo | Diagnostic bioinformatics | GSE36961; GSE141910 | RASD1, CDC42EP4, MYH6, FCN3 | LASSO; SVM-RFE; PPI | Four-gene diagnostic panel; AUC > 0.9 | Inflammatory response; complement; VEGFA–VEGFR2; apoptosis | ECM regulatory links | No outcomes | 4—Secondary datasets; ML focus |

| Gong 2024 [27] | China; multi-dataset | Bioinformatic + qPCR | GSE32453 & GSE36961 | Immune infiltration (macrophages, NK, CD4 memory) | CIBERSORT; PPI; qPCR | Hub genes FOS, CD86, CD68, BDNF linked to immune-fibrotic signature | MAPK; PI3K-Akt; NF-κB | Immune infiltration tracks ECM genes | Arrhythmic substrate inferred | 4—Limited validation |

| Zhang 2021 [25] | China | RNA-seq re-analysis + in vitro | GSE180313; GSE130036; AC16 cells | lncRNA MIR210HG–BPIFC; CD8+/naïve CD4+ signatures | WGCNA; ceRNA; qPCR | MIR210HG–BPIFC down → ↑ CD8+, ↓ naïve CD4+ | IL-6, TNF-α cytokine–lncRNA interplay | Immune-ECM linkage (inferred) | — | 3–4—Mechanism inferred; small validation |

| Marketou 2015 [36] | Greece; biomarker study | Prospective cohort | 54 HCM/40 controls | IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17A; endothelial function | ELISA; echo | ↑ IL-6/TNF-α associated with LVH & diastolic dysfunction | Systemic inflammation; endothelial-immune crosstalk | Cytokines associate with microvascular impairment/fibrosis | Trend to higher arrhythmic risk with cytokine load | 3—Systemic markers; no long FU |

| Hou 2024 [24] | China; discovery/validation | Bioinformatic immune-necroptosis | GSE130036; GSE141910 | Necroptosis-related genes (CYBB, BCL2, JAK2) | NRDEG; PPI/CytoHubba; CIBERSORT | Necroptosis signature activated in HCM | HIF-1; NOD-like receptor; inflammatory signaling | Links to ECM/inflammation | Diagnostic ROC only | 4—In silico; needs tissue validation |

| Zhang 2024 [22] | China; RNA Seq | Bioinformatics (RNA-Seq) and in vitro validation | HCM Patients: 13 (GSE180313) + 28 (GSE130036) Healthy Controls: 7 (GSE180313) + 9 (GSE130036) | Naive CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells | RNA-Seq, qRT-PCR, CIBERSORTx | Immune cell infiltration analysis | CD8+ T cells inreased and naive CD4+ T cells decreased resting Mast cells decreased | Fibrosis grade mirrors proteomic signature | LV mass & diastolic indices correlate | 3—Tissue–plasma translational link |

| Zhuo 2025 [30] | China | Integrative bioinfo + wet-lab | GSE36961; GSE141910; NRCM | JAK2, EDNRA, KCNA5, DNAJC15, CA3, PRKCD, KLF2 | LASSO/SVM-RFE; qRT-PCR/IF | Oxidative-stress gene panel → apoptosis & immune shift | ROS; apoptosis; cytokine signaling | OS-DEGs correlate with ECM remodeling | In vitro confirmation; no outcomes | 3–4—Robust pipeline; no patient outcomes |

| Cai 2025 [28] | China; systems bioinfo | WGCNA + ML with validation | GSE36961; GSE89714 | IGFBP3, JAK2 (energy-immune cross-talk) | WGCNA; LASSO/SVM-RFE; ssGSEA | Energy-metabolism signature with immune skew | IL-6–JAK–STAT; insulin resistance | Network ties to ECM/metabolic remodeling | Drug predictions: ruxolitinib, celecoxib | 4—Hypothesis-generating |

| Cao 2025 [35] | China/USA; pooled RNA-seq | Meta-analysis of RNA-seq | 9 datasets (109 HCM/210 ctrl) | ST2/IL1RL1; immune deconvolution | DESeq2; CIBERSORTx; PPI | ST2 markedly down; broad inflammatory dysregulation | Correlations: IL-6, CD163; ↓ Tregs, ↑ neutrophils | ST2 network tied to profibrotic responses | No outcomes | 3–4—Consistent cross-dataset signal |

| Wang 2025 [33] | China; national consortium | Integrative multi-omics + qPCR | GSE36961; GSE141910; qRT-PCR (16/16) | Tregs: FOXP3, IL2RA, CTLA4 | WGCNA; RF/LASSO; CIBERSORTx; docking | Treg-associated biomarkers are reduced in HCM | IL-2/STAT5; NF-κB; TGF-β | Treg ↓ links to ECM genes (COL1A1, FN1, MMP2) | Indirect arrhythmic susceptibility | 3–4—Translational signal; no longitudinal data |

| He 2025 [34] | China; Single-center study. | Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization (MR) | 108 patients with HCM | Eff-memory CD4+/CD8+, Tregs (protective) vs. CD8dim, CCR2+ DCs (risk) | IVW; MR-Egger; sensitivity | 31 immune cell types causally linked to HCM | IL-2/Treg axis; immune activation | Inferred immune-driven remodeling | No functional outcomes | 1–2—Causal inference; needs tissue proof |

| Ali 2025 [41] | USA; multi-species | Translational single-nuclei | Human n = 5; feline n = 7; mouse n = 4 | Immune/non-CM clusters; fibroblast crosstalk | snRNA-seq; GO enrichment | Conserved hypertrophy/energy programs; immune heterogeneity | Calcium/sarcomeric; oxidative metabolism | ECM/fibrosis pathways enriched in non-CM | Not assessed | 2—High-resolution; cross-species |

| Category | Key Molecules/ Genes | Associated Immune Cells/Pathways | Main Findings | Biological/ Clinical Implications | Dataset (GEO/GSE) | Supporting Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. m6A RNA Methylation Regulators | IGFBP3, YTHDC1 | Increase in activated dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, Tregs; TNFα–NFκB, IL6–JAK–STAT3 signaling | IGFBP3 upregulation correlates with inflammatory and angiogenic gene signatures; YTHDC1 is linked to mitophagy suppression and metabolic dysregulation | Epigenetic m6A modifications amplify immune and fibrotic remodeling; potential m6A-targeted therapies. | GSE36961/GSE89714 | Li 2022 [23]; Cai 2025 [28] |

| 2. lncRNA–mRNA Regulatory Pair | MIR210HG–BPIFC | Decrease in naïve CD4+ T cells; Increase in CD8+ T cells | Downregulation disrupts T-cell balance and promotes cytotoxic infiltration in HCM myocardium | lncRNA network dysregulation modulates immune microenvironment; potential diagnostic target | GSE141910/GSE32453 | Zhang 2024 [22] |

| 3. Necroptosis-Related Genes | CYBB, BCL2, JAK2 | Correlated with M2 macrophage infiltration; TNF, IL-17, JAK–STAT signaling | Necroptosis pathways are enriched in HCM; an imbalance between cell death and repair promotes fibrosis. | Targeting the necroptosis–macrophage axis may reduce inflammatory remodeling. | GSE36961 | Hou 2024 [24] |

| 4. Downregulated Hub Genes | CD14, ITGB2, C1QB, CD163, HCLS1, ALOX5AP, PLEK, C1QC, FCER1G, TYROBP | Innate immune and complement activation pathways | Reduced expression indicates impaired immune surveillance and macrophage polarization. | Early diagnostic markers and targets for anti-inflammatory therapies | GSE141910/GSE36961 | Wu 2022 [26]; Zhang 2021 [25] |

| 5. Immune Infiltration Patterns | — | Increase in M0 macrophages, monocytes, NK cells; Decrease in M2 macrophages, Tregs, Th1 cells | CIBERSORT and ssGSEA analyses demonstrate an immune imbalance toward pro-inflammatory phenotypes | Chronic innate activation drives fibrosis and arrhythmogenic remodeling | GSE32453/GSE36961/GSE141910 | Zhang 2021 [25]; Gong 2024 [27] |

| 6. Machine-Learning-Derived Diagnostic Genes | RASD1, CDC42EP4, MYH6, FCN3 | Immune-modulatory and structural signaling networks | High AUC (>0.85) for differentiating HCM from controls in ML models | Promising biomarkers for computational diagnostic screening | GSE36961/GSE141910 | You & Dong 2023 [29] |

| 7. Therapeutic Targets (Predicted) | IGFBP3, JAK2, YTHDC1, CYBB, BCL2 | JAK–STAT and COX-2 signaling | Ruxolitinib, peficitinib (JAK inhibitors), and celecoxib (COX-2 modulator) are predicted to target core pathways. | Drug repurposing offers precision immunometabolic therapy options | GSE36961/GSE89714 | Cai 2025 [28]; Zhuo 2025 [30] |

| 8. Imaging–Molecular Correlation | CD3+ T cells, CAF (collagen area fraction) | Fibrosis and inflammation quantified by EMB vs. CMR | High CAF + CD3+ T-cell infiltration predicts poor outcomes even without LGE on CMR | Combining molecular and imaging markers enhances risk stratification and diagnostic accuracy | — | Shintani 2022 [31]; Laird 2023 [32] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Menezes Junior, A.d.S.; de Oliveira, H.L.; de Lima, K.B.A.; Botelho, S.M.; Wastowski, I.J. T-Cell-Driven Immunopathology and Fibrotic Remodeling in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Translational Scoping Review. Cells 2026, 15, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010061

Menezes Junior AdS, de Oliveira HL, de Lima KBA, Botelho SM, Wastowski IJ. T-Cell-Driven Immunopathology and Fibrotic Remodeling in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Translational Scoping Review. Cells. 2026; 15(1):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010061

Chicago/Turabian StyleMenezes Junior, Antonio da Silva, Henrique Lima de Oliveira, Khissya Beatryz Alves de Lima, Silvia Marçal Botelho, and Isabela Jubé Wastowski. 2026. "T-Cell-Driven Immunopathology and Fibrotic Remodeling in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Translational Scoping Review" Cells 15, no. 1: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010061

APA StyleMenezes Junior, A. d. S., de Oliveira, H. L., de Lima, K. B. A., Botelho, S. M., & Wastowski, I. J. (2026). T-Cell-Driven Immunopathology and Fibrotic Remodeling in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Translational Scoping Review. Cells, 15(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010061