The Temozolomide Mutational Signature: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities in Primary Brain Tumor Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

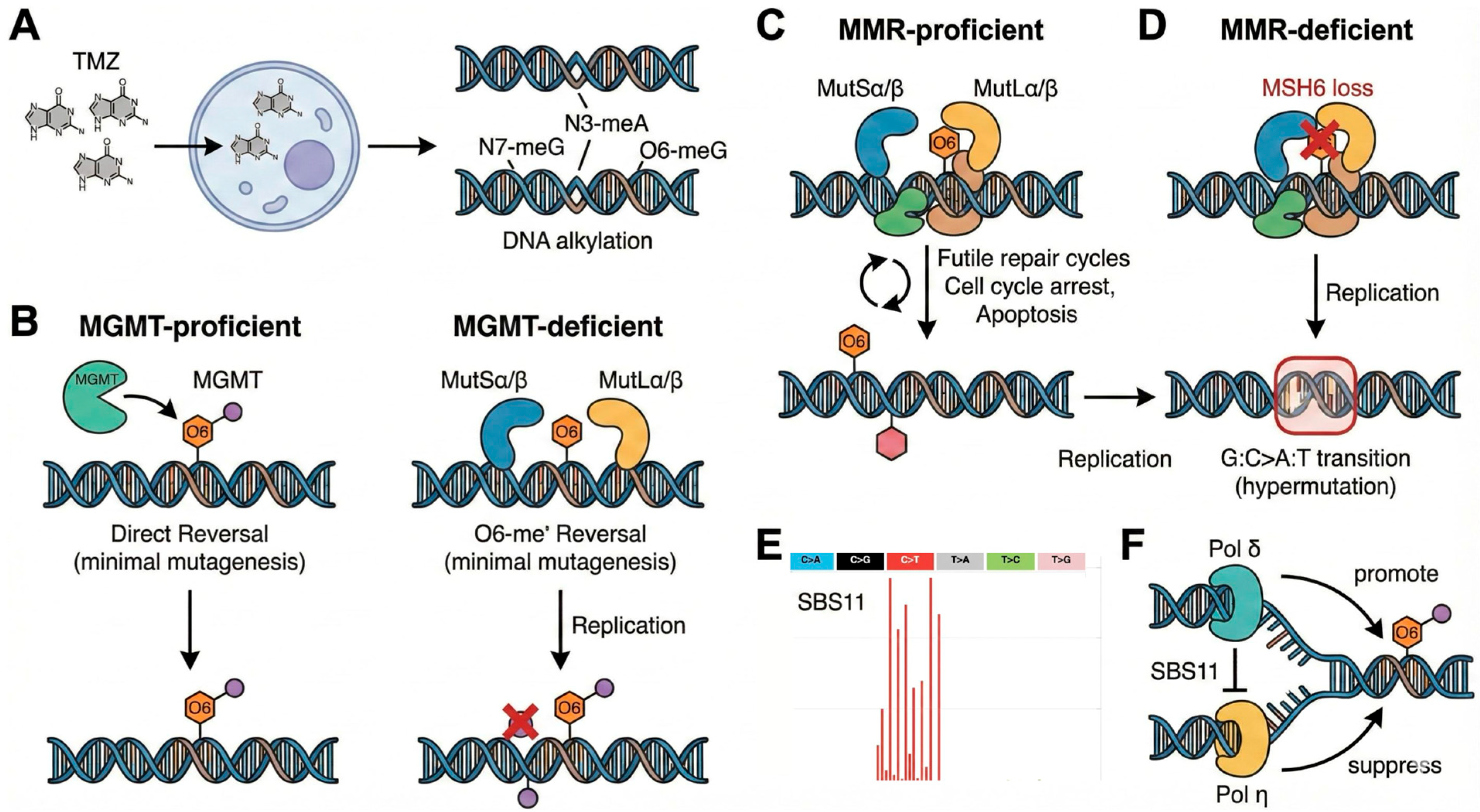

2. Molecular Mechanisms of the TMZ Signature

2.1. The Mechanistic Core: DNA Alkylation, MGMT, and Mismatch Repair

2.2. The SBS11 Mutational Signature

2.3. MMR Deficiency: Amplifier of the Hypermutator Phenotype

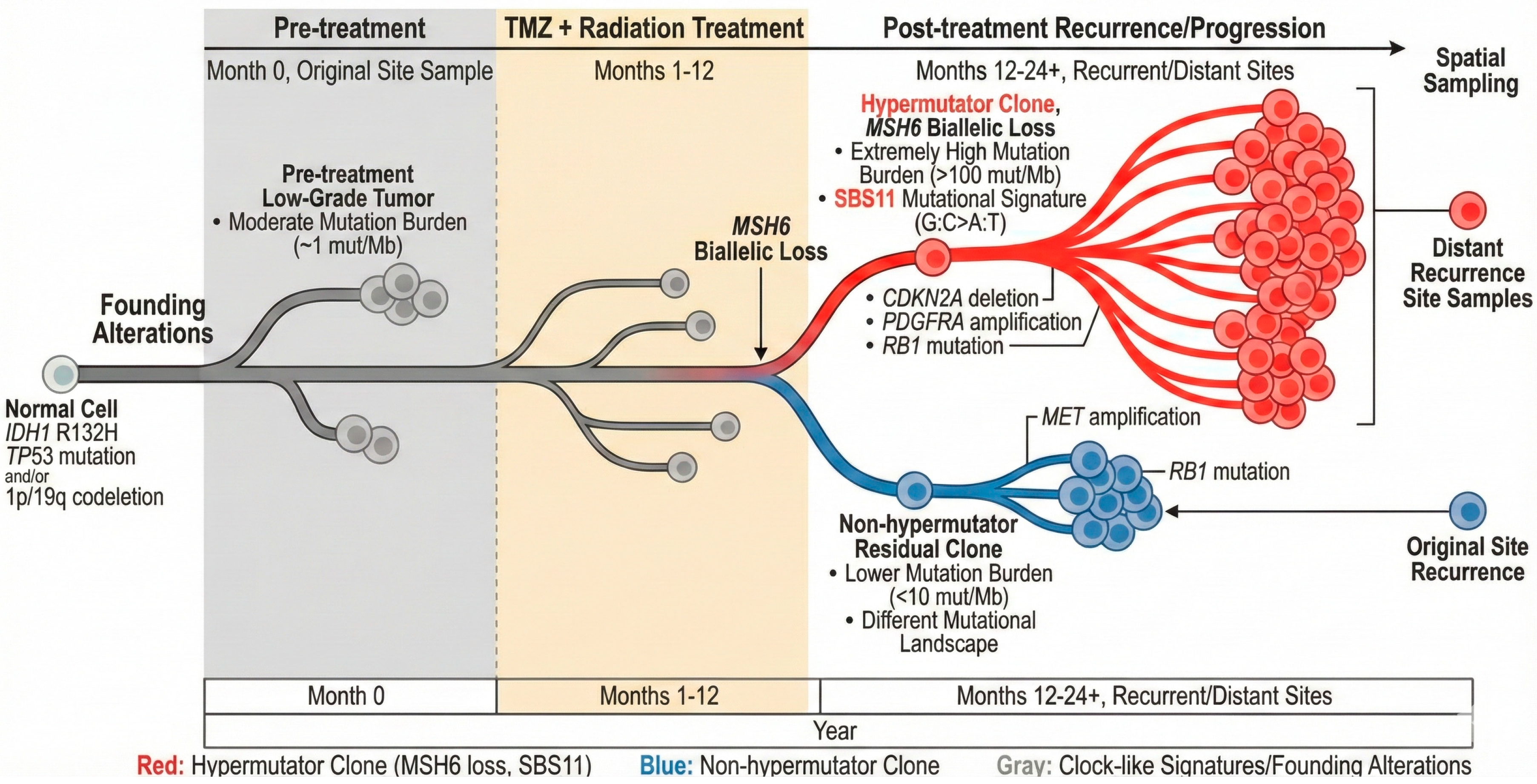

3. Tumor Evolution Under TMZ Pressure

3.1. Evolutionary Trajectories: Clonal Dynamics and Malignant Transformation

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity

3.3. Cellular State Plasticity and Glioma Stem Cell Dynamics Under TMZ Pressure

4. Clinical Evidence on TMZ-Induced Mutagenesis

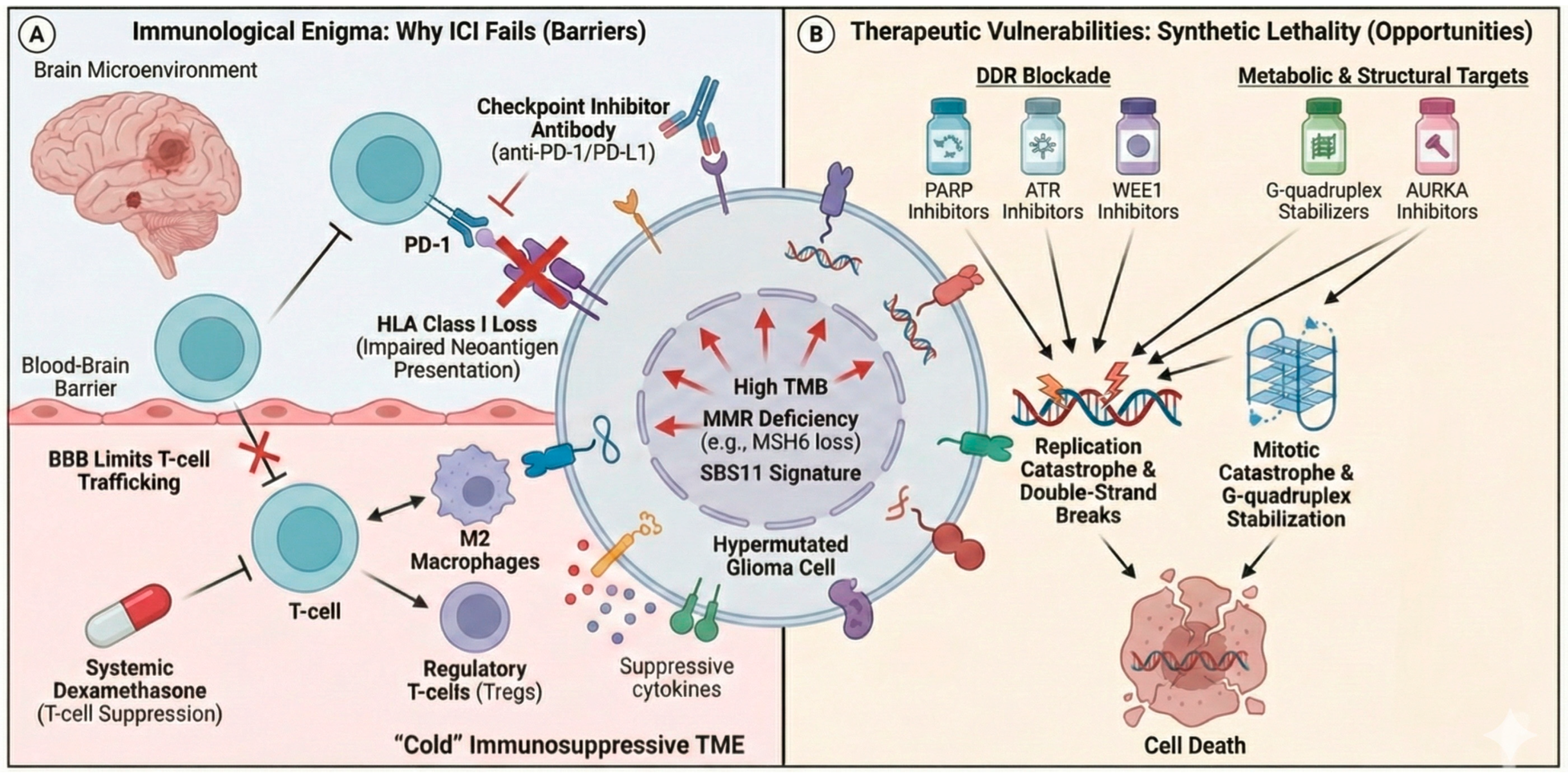

4.1. The Immunogenic Enigma: TMB, Neoantigens, and Immunotherapy in Glioblastoma

4.2. Acquired Resistance Mechanisms

5. Therapeutic Opportunities and Strategies

5.1. Targeting the DNA Damage Response

5.2. Reimagining Immunotherapy for Hypermutated Gliomas

5.3. Exploiting Acquired Vulnerabilities

6. Real-Time Monitoring with Liquid Biopsy from CSF and Plasma

7. Future Directions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weller, M.; Wen, P.Y.; Chang, S.M.; Dirven, L.; Lim, M.; Monje, M.; Reifenberger, G. Glioma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, F.; Matz, M.; Stiller, C.; You, H.; Marcos Gragera, R.; Valkov, M.Y.; Bulliard, J.-L.; De, P.; Morrison, D.; Wanner, M.; et al. Global Survival Trends for Brain Tumors, by Histology: Analysis of Individual Records for 556,237 Adults Diagnosed in 59 Countries during 2000-2014 (CONCORD-3). Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuro, A.; DeAngelis, L.M. Glioblastoma and Other Malignant Gliomas: A Clinical Review. JAMA 2013, 310, 1842–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Price, M.; Neff, C.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2016-2020. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, iv1–iv99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horbinski, C.; Nabors, L.B.; Portnow, J.; Baehring, J.; Bhatia, A.; Bloch, O.; Brem, S.; Butowski, N.; Cannon, D.M.; Chao, S.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 2.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, M.R.; Wang, M.; Aldape, K.D.; Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Jaeckle, K.A.; Armstrong, T.S.; Wefel, J.S.; Won, M.; Blumenthal, D.T.; et al. Dose-Dense Temozolomide for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: A Randomized Phase III Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4085–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Janzer, R.C.; Ludwin, S.K.; Allgeier, A.; Fisher, B.; Belanger, K.; et al. Effects of Radiotherapy with Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide versus Radiotherapy Alone on Survival in Glioblastoma in a Randomised Phase III Study: 5-Year Analysis of the EORTC-NCIC Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.G.; Garside, R.; Rogers, G.; Stein, K.; Grant, R. Temozolomide for High Grade Glioma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD007415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegi, M.E.; Diserens, A.-C.; Gorlia, T.; Hamou, M.-F.; de Tribolet, N.; Weller, M.; Kros, J.M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Mason, W.; Mariani, L.; et al. MGMT Gene Silencing and Benefit from Temozolomide in Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, J.; Cote, D.J.; Kang, K.; Briggs, R.G.; Gomez, D.; Prasad, A.; Daggupati, S.; Sisti, J.; Chow, F.; Attenello, F.; et al. Treatment Practices and Survival Outcomes for IDH-Wildtype Glioblastoma Patients According to MGMT Promoter Methylation Status: Insights from the U.S. National Cancer Database. J. Neuro Oncol. 2025, 172, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinslow, C.J.; Mercurio, A.; Kumar, P.; Rae, A.I.; Siegelin, M.D.; Grinband, J.; Taparra, K.; Upadhyayula, P.S.; McKhann, G.M.; Sisti, M.B.; et al. Association of MGMT Promoter Methylation with Survival in Low-Grade and Anaplastic Gliomas After Alkylating Chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Yu, Y.; Grimmer, M.R.; Wahl, M.; Chang, S.M.; Costello, J.F. Temozolomide-Associated Hypermutation in Gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthel, F.P.; Johnson, K.C.; Varn, F.S.; Moskalik, A.D.; Tanner, G.; Kocakavuk, E.; Anderson, K.J.; Abiola, O.; Aldape, K.; Alfaro, K.D.; et al. Longitudinal Molecular Trajectories of Diffuse Glioma in Adults. Nature 2019, 576, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucab, J.E.; Zou, X.; Morganella, S.; Joel, M.; Nanda, A.S.; Nagy, E.; Gomez, C.; Degasperi, A.; Harris, R.; Jackson, S.P.; et al. A Compendium of Mutational Signatures of Environmental Agents. Cell 2019, 177, 821–836.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Kim, J.; Haradhvala, N.J.; Huang, M.N.; Tian Ng, A.W.; Wu, Y.; Boot, A.; Covington, K.R.; Gordenin, D.A.; Bergstrom, E.N.; et al. The Repertoire of Mutational Signatures in Human Cancer. Nature 2020, 578, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, M.R.; Sugiyama, T. Biochemical Reconstitution of Temozolomide-Induced Mutational Processes. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, D.D.; Hinić, S.; Kroeze, E.; Gorris, M.A.; Schreibelt, G.; Middelkamp, S.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Bladergroen, R.; Verrijp, K.; Hoogerbrugge, N.; et al. Unraveling Mutagenic Processes Influencing the Tumor Mutational Patterns of Individuals with Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, A.L.; Thongararm, P.; Fedeles, B.I.; Yau, J.; Kay, J.E.; Corrigan, J.J.; Chancharoen, M.; Chawanthayatham, S.; Samson, L.D.; Carrasco, S.E.; et al. Molecular Origins of Mutational Spectra Produced by the Environmental Carcinogen N-Nitrosodimethylamine and SN1 Chemotherapeutic Agents. NAR Cancer 2023, 5, zcad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touat, M.; Li, Y.Y.; Boynton, A.N.; Spurr, L.F.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; Bohrson, C.L.; Cortes-Ciriano, I.; Birzu, C.; Geduldig, J.E.; Pelton, K.; et al. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications of Hypermutation in Gliomas. Nature 2020, 580, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Stevens, M.F.G.; Bradshaw, T.D. Temozolomide: Mechanisms of Action, Repair and Resistance. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 5, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, I.-L.; Perez, A.R.; Lew, R.J.; Sun, X.; Baldwin, A.; Zhu, Y.K.; Shah, M.M.; Berger, M.S.; Doudna, J.A.; Fellmann, C. Targeting the Non-Coding Genome and Temozolomide Signature Enables CRISPR-Mediated Glioma Oncolysis. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.; Grimmer, M.R.; Hilz, S.; Solomon, D.A.; Choi, S.; Wahl, M.; Mazor, T.; Hong, C.; Shai, A.; et al. Temozolomide-Induced Hypermutation Is Associated with Distant Recurrence and Reduced Survival after High-Grade Transformation of Low-Grade IDH-Mutant Gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1872–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, I.-H.; Cho, H.J.; Park, C.-K.; Jung, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.; Nam, S.H.; Kim, B.S.; Johnson, M.D.; Kong, D.-S.; et al. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Primary Glioblastoma Genome. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degasperi, A.; Zou, X.; Amarante, T.D.; Martinez-Martinez, A.; Koh, G.C.C.; Dias, J.M.L.; Heskin, L.; Chmelova, L.; Rinaldi, G.; Wang, V.Y.W.; et al. Substitution Mutational Signatures in Whole-Genome-Sequenced Cancers in the UK Population. Science 2022, 376, abl9283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.; Sitko, L.K.; Khoirunnisa, R.; Navarro-Aguad, F.; Samuel, D.M.; Park, H.; Cheon, B.; Mutsnaini, L.; Lee, J.; Otlu, B.; et al. Comprehensive Whole-Genome Sequencing Reveals Origins of Mutational Signatures Associated with Aging, Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Temozolomide Chemotherapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkae1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Tesileanu, C.M.S.; Kocakavuk, E.; Johnson, K.C.; Lee, J.; Erson-Omay, Z.; Heo, C.; Aldape, K.; Amin, S.B.; Anderson, K.J.; et al. Tumor-Initiating Genetics and Therapy Drive Divergent Molecular Evolution in IDH-Mutant Gliomas. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S.; Miao, J.; Cahill, D.P.; Iafrate, A.J.; Aldape, K.; Nutt, C.L.; Louis, D.N. MSH6 Mutations Arise in Glioblastomas during Temozolomide Therapy and Mediate Temozolomide Resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 4622–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.; Smith, R.; Cahill, D.P.; Stephens, P.; Stevens, C.; Teague, J.; Greenman, C.; Edkins, S.; Bignell, G.; Davies, H.; et al. A Hypermutation Phenotype and Somatic MSH6 Mutations in Recurrent Human Malignant Gliomas after Alkylator Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 3987–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, T.; Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Wang, P.; Shi, Q.; Qian, X.; Miao, F.; Shen, Z.; et al. MEX3A Impairs DNA Mismatch Repair Signaling and Mediates Acquired Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 4234–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.E.; Mazor, T.; Hong, C.; Barnes, M.; Aihara, K.; McLean, C.Y.; Fouse, S.D.; Yamamoto, S.; Ueda, H.; Tatsuno, K.; et al. Mutational Analysis Reveals the Origin and Therapy-Driven Evolution of Recurrent Glioma. Science 2014, 343, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautajoki, K.J.; Jaatinen, S.; Hartewig, A.; Tiihonen, A.M.; Annala, M.; Salonen, I.; Valkonen, M.; Simola, V.; Vuorinen, E.M.; Kivinen, A.; et al. Genomic Characterization of IDH-Mutant Astrocytoma Progression to Grade 4 in the Treatment Setting. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, D.; Wach, J.; Barrantes-Freer, A.; Nicolay, N.H.; Güresir, E.; Seidel, C. Homozygous CDKN2A/B Deletions in Low- and High-Grade Glioma: A Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data and Predictive Values of P16 Immunohistochemistry Testing. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottoriva, A.; Spiteri, I.; Piccirillo, S.G.M.; Touloumis, A.; Collins, V.P.; Marioni, J.C.; Curtis, C.; Watts, C.; Tavaré, S. Intratumor Heterogeneity in Human Glioblastoma Reflects Cancer Evolutionary Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4009–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.F.; Gopakumar, S.; Juratli, T.A.; Eyüpoglu, I.Y.; Rao, G.; Mandel, J.J.; Jalali, A. Discontiguous Recurrences of IDH-Wildtype Glioblastoma Share a Common Origin with the Initial Tumor and Are Frequently Hypermutated. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.M.; Shah, R.H.; Pentsova, E.I.; Pourmaleki, M.; Briggs, S.; Distefano, N.; Zheng, Y.; Skakodub, A.; Mehta, S.A.; Campos, C.; et al. Tracking Tumour Evolution in Glioma through Liquid Biopsies of Cerebrospinal Fluid. Nature 2019, 565, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neftel, C.; Laffy, J.; Filbin, M.G.; Hara, T.; Shore, M.E.; Rahme, G.J.; Richman, A.R.; Silverbush, D.; Shaw, M.L.; Hebert, C.M.; et al. An Integrative Model of Cellular States, Plasticity, and Genetics for Glioblastoma. Cell 2019, 178, 835–849.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Wang, K.; Lu, T.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, K. Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptome Analyses Reveal MAZ(+) NPC-like Clusters as Key Role Contributing to Glioma Recurrence and Drug Resistance. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumbaca, B.; Huggins, J.R.; Birtwistle, M.R.; Gallo, J.M. Network Analyses of Brain Tumor Multiomic Data Reveal Pharmacological Opportunities to Alter Cell State Transitions. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2025, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garros-Regulez, L.; Aldaz, P.; Arrizabalaga, O.; Moncho-Amor, V.; Carrasco-Garcia, E.; Manterola, L.; Moreno-Cugnon, L.; Barrena, C.; Villanua, J.; Ruiz, I.; et al. mTOR Inhibition Decreases SOX2-SOX9 Mediated Glioma Stem Cell Activity and Temozolomide Resistance. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2016, 20, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Liao, B.; Gong, S.; Guo, H.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Wu, N. Temozolomide Promotes Glioblastoma Stemness Expression through Senescence-Associated Reprogramming via HIF1α/HIF2α Regulation. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samstein, R.M.; Lee, C.-H.; Shoushtari, A.N.; Hellmann, M.D.; Shen, R.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Barron, D.A.; Zehir, A.; Jordan, E.J.; Omuro, A.; et al. Tumor Mutational Load Predicts Survival after Immunotherapy across Multiple Cancer Types. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.A.; Brandes, A.A.; Omuro, A.; Mulholland, P.; Lim, M.; Wick, A.; Baehring, J.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Roth, P.; Bähr, O.; et al. Effect of Nivolumab vs Bevacizumab in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma: The CheckMate 143 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, M.; Weller, M.; Idbaih, A.; Steinbach, J.; Finocchiaro, G.; Raval, R.R.; Ansstas, G.; Baehring, J.; Taylor, J.W.; Honnorat, J.; et al. Phase III Trial of Chemoradiotherapy with Temozolomide plus Nivolumab or Placebo for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma with Methylated MGMT Promoter. Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omuro, A.; Brandes, A.A.; Carpentier, A.F.; Idbaih, A.; Reardon, D.A.; Cloughesy, T.; Sumrall, A.; Baehring, J.; van den Bent, M.; Bähr, O.; et al. Radiotherapy Combined with Nivolumab or Temozolomide for Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma with Unmethylated MGMT Promoter: An International Randomized Phase III Trial. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, P.; Meehan, B.; Sabri, S.; Jamali, F.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Choi, D.; Garnier, D.; Kitange, G.; Glennon, K.I.; Paccard, A.; et al. Detection of Temozolomide-Induced Hypermutation and Response to PD-1 Checkpoint Inhibitor in Recurrent Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, G.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Lazzari, L.; Pietrantonio, F.; Amatu, A.; Macagno, M.; Barault, L.; Cassingena, A.; Bartolini, A.; Luraghi, P.; et al. Temozolomide Treatment Alters Mismatch Repair and Boosts Mutational Burden in Tumor and Blood of Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 1656–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, F.; Raimondi, A.; Pagani, F.; Lonardi, S.; Salvatore, L.; Cremolini, C.; Murgioni, S.; Randon, G.; Palermo, F.; Antonuzzo, L.; et al. Temozolomide Followed by Combination with Low-Dose Ipilimumab and Nivolumab in Patients with Microsatellite-Stable, O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase-Silenced Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The MAYA Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, J.H.; Gunn, M.D.; Fecci, P.E.; Ashley, D.M. Brain Immunology and Immunotherapy in Brain Tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.-H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A.; et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woroniecka, K.I.; Rhodin, K.E.; Chongsathidkiet, P.; Keith, K.A.; Fecci, P.E. T-Cell Dysfunction in Glioblastoma: Applying a New Framework. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3792–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Ali, H.; Lathia, J.D.; Chen, P. Immunotherapy for Glioblastoma: Current State, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1354–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmink, B.A.; Reddy, S.M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, S.; Basar, R.; Thakur, R.; Yizhak, K.; Sade-Feldman, M.; Blando, J.; Han, G.; et al. B Cells and Tertiary Lymphoid Structures Promote Immunotherapy Response. Nature 2020, 577, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Luan, S.; Xu, W.; Gao, Y. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Gliomas: Impact on Tumour Immunity and Progression. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGranahan, N.; Furness, A.J.S.; Rosenthal, R.; Ramskov, S.; Lyngaa, R.; Saini, S.K.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Wilson, G.A.; Birkbak, N.J.; Hiley, C.T.; et al. Clonal Neoantigens Elicit T Cell Immunoreactivity and Sensitivity to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Science 2016, 351, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Zheng, S.; Amini, S.S.; Virk, S.M.; Mikkelsen, T.; Brat, D.J.; Grimsby, J.; Sougnez, C.; Muller, F.; Hu, J.; et al. Whole-Genome and Multisector Exome Sequencing of Primary and Post-Treatment Glioblastoma Reveals Patterns of Tumor Evolution. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuring, C.; Follin, E.; Geironson, L.; Freyhult, E.; Junghans, V.; Harndahl, M.; Buus, S.; Paulsson, K.M. HLA Class I Is Most Tightly Linked to Levels of Tapasin Compared with Other Antigen-Processing Proteins in Glioblastoma. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejo, T.; Matsushita, H.; Karasaki, T.; Nomura, M.; Saito, K.; Tanaka, S.; Takayanagi, S.; Hana, T.; Takahashi, S.; Kitagawa, Y.; et al. Reduced Neoantigen Expression Revealed by Longitudinal Multiomics as a Possible Immune Evasion Mechanism in Glioma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorgulescu, J.B.; Gokhale, P.C.; Speranza, M.C.; Eschle, B.K.; Poitras, M.J.; Wilkens, M.K.; Soroko, K.M.; Chhoeu, C.; Knott, A.; Gao, Y.; et al. Concurrent Dexamethasone Limits the Clinical Benefit of Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, D.P.; Levine, K.K.; Betensky, R.A.; Codd, P.J.; Romany, C.A.; Reavie, L.B.; Batchelor, T.T.; Futreal, P.A.; Stratton, M.R.; Curry, W.T.; et al. Loss of the Mismatch Repair Protein MSH6 in Human Glioblastomas Is Associated with Tumor Progression during Temozolomide Treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 2038–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Liu, B.; Lian, C.; Doycheva, D.M.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; He, Z.; Yang, Z.; Huang, Q.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA AC003092.1 Promotes Temozolomide Chemosensitivity through miR-195/TFPI-2 Signaling Modulation in Glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, W.; Mao, P.; Wang, J.; Jing, J.; Sun, Q.; Wang, M.; Yu, X. Identification of a Three-Long Non-Coding RNA Signature for Predicting Survival of Temozolomide-Treated Isocitrate Dehydrogenase Mutant Low-Grade Gliomas. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Hao, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, Z. The Involvement of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Glioma: From Early Detection to Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 897754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhuang, S.; Chen, S.; Wu, B.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, W. Targeting the Dual miRNA/BMP2 Network: LncRNA H19-Mediated Temozolomide Resistance Unveils Novel Therapeutic Strategies in Glioblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1577221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, K.; Tanaka, K.; Akhavan, D.; Babic, I.; Gini, B.; Matsutani, T.; Iwanami, A.; Liu, F.; Villa, G.R.; Gu, Y.; et al. mTOR Complex 2 Controls Glycolytic Metabolism in Glioblastoma through FoxO Acetylation and Upregulation of C-Myc. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, T.; Wang, Y.; Chang, L.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Chen, F.; Gong, X.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Primary and Recurrent Gliomas Reveals Clinical Outcome Related Molecular Features. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaiyan, P.; Won, M.; Wen, P.Y.; Rojiani, A.M.; Werner-Wasik, M.; Shih, H.A.; Ashby, L.S.; Michael Yu, H.-H.; Stieber, V.W.; Malone, S.C.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Study of Everolimus in Combination with Chemoradiation in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: Results of NRG Oncology RTOG 0913. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babak, S.; Mason, W.P. mTOR Inhibition in Glioblastoma: Requiem for a Dream? Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 584–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lan, Y.; Zhong, X.; Luo, X.; Yang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zuo, B.; Zeng, T.; et al. Histone H3K9 Lactylation Confers Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma via LUC7L2-Mediated MLH1 Intron Retention. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2309290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, X.; Wan, J.; Ma, L. TRIM25 Promotes Temozolomide Resistance in Glioma by Regulating Oxidative Stress and Ferroptotic Cell Death via the Ubiquitination of Keap1. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2103–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Gao, G.; Cao, Z.; Guan, Z.; Jia, B.; Wang, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; et al. Exosome-Transmitted circCABIN1 Promotes Temozolomide Resistance in Glioblastoma via Sustaining ErbB Downstream Signaling. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, L.; Xuan, S.; Liu, Z.; Weng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dai, K.; Gu, A.; Zhao, P. Global Analysis of Iron Metabolism-Related Genes Identifies Potential Mechanisms of Gliomagenesis and Reveals Novel Targets. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilbash, S.H.; Gupta, S.K.; Chang, K.; Kawashima, R.; Parrish, K.E.; Carlson, B.L.; Bakken, K.K.; Mladek, A.C.; Schroeder, M.A.; Decker, P.A.; et al. Restricted Delivery of Talazoparib Across the Blood-Brain Barrier Limits the Sensitizing Effects of PARP Inhibition on Temozolomide Therapy in Glioblastoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groseclose, M.R.; Barry, J.A.; Skedzielewski, T.; Pang, Y.; Li, Y.; McDermott, G.; Deutsch, J.; Balabhadrapatruni, C.; Benson, W.; Lim, D.; et al. Assessment of Brain Penetration and Tumor Accumulation of Niraparib and Olaparib: Insights from Multimodal Imaging in Preclinical Models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cella, E.; Bosio, A.; Persico, P.; Caccese, M.; Padovan, M.; Losurdo, A.; Maccari, M.; Cerretti, G.; Ius, T.; Minniti, G.; et al. PARP Inhibitors in Gliomas: Mechanisms of Action, Current Trends and Future Perspectives. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2024, 131, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; De Gooijer, M.C.; Roig, E.M.; Buil, L.C.M.; Christner, S.M.; Beumer, J.H.; Würdinger, T.; Beijnen, J.H.; Van Tellingen, O. ABCB1, ABCG2, and PTEN Determine the Response of Glioblastoma to Temozolomide and ABT-888 Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2703–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ran, X.; Leung, W.; Kawale, A.; Saxena, S.; Ouyang, J.; Patel, P.S.; Dong, Y.; Yin, T.; Shu, J.; et al. ATR Inhibition Induces Synthetic Lethality in Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cells and Augments Immunotherapy. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 929–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesa, S.; Sule, A.; Sundaram, R.K.; Bindra, R.S. Mismatch Repair Proteins Play a Role in ATR Activation upon Temozolomide Treatment in MGMT-Methylated Glioblastoma. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinski, M.; Bowden, N.A.; Graves, M.C.; Fay, M.; Day, B.W.; Stringer, B.W.; Tooney, P.A. ATR Inhibition Using Gartisertib Enhances Cell Death and Synergises with Temozolomide and Radiation in Patient-Derived Glioblastoma Cell Lines. Oncotarget 2024, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Noorbakhsh, S.I.; Sundaram, R.K.; Kalathil, A.N.; Ganesa, S.; Jia, L.; Breslin, H.; Burgenske, D.M.; Gilad, O.; Sarkaria, J.N.; et al. Temozolomide Sensitizes MGMT-Deficient Tumor Cells to ATR Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4331–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, W.C.; Abdoli, A.; An, X.; Auger, A.; Beaulieu, P.; Bernatchez, M.; Caron, C.; Chefson, A.; Crane, S.; Diallo, M.; et al. Discovery of the Potent and Selective ATR Inhibitor Camonsertib (RP-3500). J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 2349–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, S.; Li, P.; Xu, L.; Xu, X.; Hu, X.; Zeng, X.; et al. Discovery of Preclinical Candidate AD1058 as a Highly Potent, Selective, and Brain-Penetrant ATR Inhibitor for the Treatment of Advanced Malignancies. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 12735–12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Liu, W.; Zheng, X.; Yang, J.; Ye, X.; Weng, Y.; Fan, T.; et al. Discovery of the Clinical Candidate YY2201 as a Highly Potent and Selective ATR Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 5292–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.A.; Manasa, P.; Chandrasekaran, J. Revisiting CHK1 and WEE1 Kinases as Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmello, C.; Zhao, J.; Chen, L.; Gould, A.; Castro, B.; Arrieta, V.A.; Zhang, D.Y.; Kim, K.-S.; Kanojia, D.; Zhang, P.; et al. Checkpoint Kinase 1/2 Inhibition Potentiates Anti-Tumoral Immune Response and Sensitizes Gliomas to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, R.; Pang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, C. Combined Inhibition of WEE1 by AZD1775 Synergistically Enhances CX-5461 Mediated DNA Damage and Induces Cytotoxicity in Glioblastoma. Tissue Cell 2025, 97, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Shklovskaya, E.; Satgunaseelan, L.; Mao, Y.; Da Silva, I.P.; Perry, K.A.; Diefenbach, R.J.; Gide, T.N.; Shivalingam, B.; Buckland, M.E.; et al. Neoadjuvant Triplet Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stritzelberger, J.; Distel, L.; Buslei, R.; Fietkau, R.; Putz, F. Acquired Temozolomide Resistance in Human Glioblastoma Cell Line U251 Is Caused by Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Can Be Overcome by Lomustine. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 20, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamuro, S.; Takahashi, M.; Satomi, K.; Sasaki, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Uchida, E.; Kawauchi, D.; Nakano, T.; Fujii, T.; Narita, Y.; et al. Lomustine and Nimustine Exert Efficient Antitumor Effects against Glioblastoma Models with Acquired Temozolomide Resistance. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 4736–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.; Hajal, C.; Ligon, K.L.; Touat, M. Revisiting an Old Therapy for New, Promising Combinations: Biology and Perspectives of Lomustine in Glioma Treatment. Neuro Oncol. 2025, noaf192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Yang, C.; Yang, S.; Zhan, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, M.; Hong, B.; et al. Blockage of EGFR/AKT and Mevalonate Pathways Synergize the Antitumor Effect of Temozolomide by Reprogramming Energy Metabolism in Glioblastoma. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 1326–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Mrid, R.; El Guendouzi, S.; Mineo, M.; El Fatimy, R. The Emerging Roles of Aberrant Alternative Splicing in Glioma. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiek, D.M.; Erdogdu, B.; Razaghi, R.; Jin, L.; Sadowski, N.; Alamillo-Ferrer, C.; Hogg, J.R.; Haddad, B.R.; Drewry, D.H.; Wells, C.I.; et al. Temozolomide-Induced Guanine Mutations Create Exploitable Vulnerabilities of Guanine-Rich DNA and RNA Regions in Drug-Resistant Gliomas. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yi, K.; Feng, J.; Cong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wu, F.; Cheng, W.; Samo, A.A.; et al. Elevated Signature of a Gene Module Coexpressed with CDC20 Marks Genomic Instability in Glioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6975–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; O’Donnell, J.P.; Salazar, C.R.; Van Brocklyn, J.R.; Barnett, K.D.; Pearl, D.K.; deCarvalho, A.C.; Ecsedy, J.A.; Brown, S.L.; Mikkelsen, T.; et al. The Selective Aurora-A Kinase Inhibitor MLN8237 (Alisertib) Potently Inhibits Proliferation of Glioblastoma Neurosphere Tumor Stem-like Cells and Potentiates the Effects of Temozolomide and Ionizing Radiation. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 73, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Andrews, D.W.; Werner-Wasik, M.; Kim, L.; Glass, J.; Bar-Ad, V.; Evans, J.J.; Farrell, C.J.; Judy, K.D.; Daskalakis, C.; et al. Phase I Trial of Alisertib with Concurrent Fractionated Stereotactic Re-Irradiation for Recurrent High Grade Gliomas. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 132, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.-M.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, H.-J.; Jiang, B.-Y.; Tang, L.-B.; Jie, G.-L.; Tu, H.-Y.; Yin, K.; Sun, H.; Liu, S.-Y.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulating Tumor DNA Profiling for Risk Stratification and Matched Treatment of Central Nervous System Metastases. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas-Camarero, S.; Pérez-Alfayate, R.; García-Barberán, V.; Gandía-González, M.L.; García-Feijóo, P.; López-Cade, I.; Lorca, V.; Casado-Fariñas, I.; Cerón, M.A.; Paz-Cabezas, M.; et al. ctDNA Detection in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma and Mutational Concordance with the Primary Tumor in a Multicenter Prospective Study of Patients with Glioma. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulhan, D.C.; Lee, J.J.-K.; Melloni, G.E.M.; Cortés-Ciriano, I.; Park, P.J. Detecting the Mutational Signature of Homologous Recombination Deficiency in Clinical Samples. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacov, A.; Ben Cohen, G.; Landau, J.; Hope, T.; Simon, I.; Rosenberg, S. Cancer Mutational Signatures Identification in Clinical Assays Using Neural Embedding-Based Representations. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, S.; Tan, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhao, F.; Li, X.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential of Cell-Free RNAs in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma for Brain Tumors. npj Precis. Onc. 2025, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yaacov, A.; Gillis, R.; Salim, J.; Katz, D.; Asna, N.; Paldor, I.; Grinshpun, A. The Temozolomide Mutational Signature: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities in Primary Brain Tumor Management. Cells 2026, 15, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010057

Yaacov A, Gillis R, Salim J, Katz D, Asna N, Paldor I, Grinshpun A. The Temozolomide Mutational Signature: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities in Primary Brain Tumor Management. Cells. 2026; 15(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleYaacov, Adar, Roni Gillis, Jaber Salim, Daniela Katz, Noam Asna, Iddo Paldor, and Albert Grinshpun. 2026. "The Temozolomide Mutational Signature: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities in Primary Brain Tumor Management" Cells 15, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010057

APA StyleYaacov, A., Gillis, R., Salim, J., Katz, D., Asna, N., Paldor, I., & Grinshpun, A. (2026). The Temozolomide Mutational Signature: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Therapeutic Opportunities in Primary Brain Tumor Management. Cells, 15(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010057