Glucose Metabolism and Innate Immune Responses in Influenza Virus Infection: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

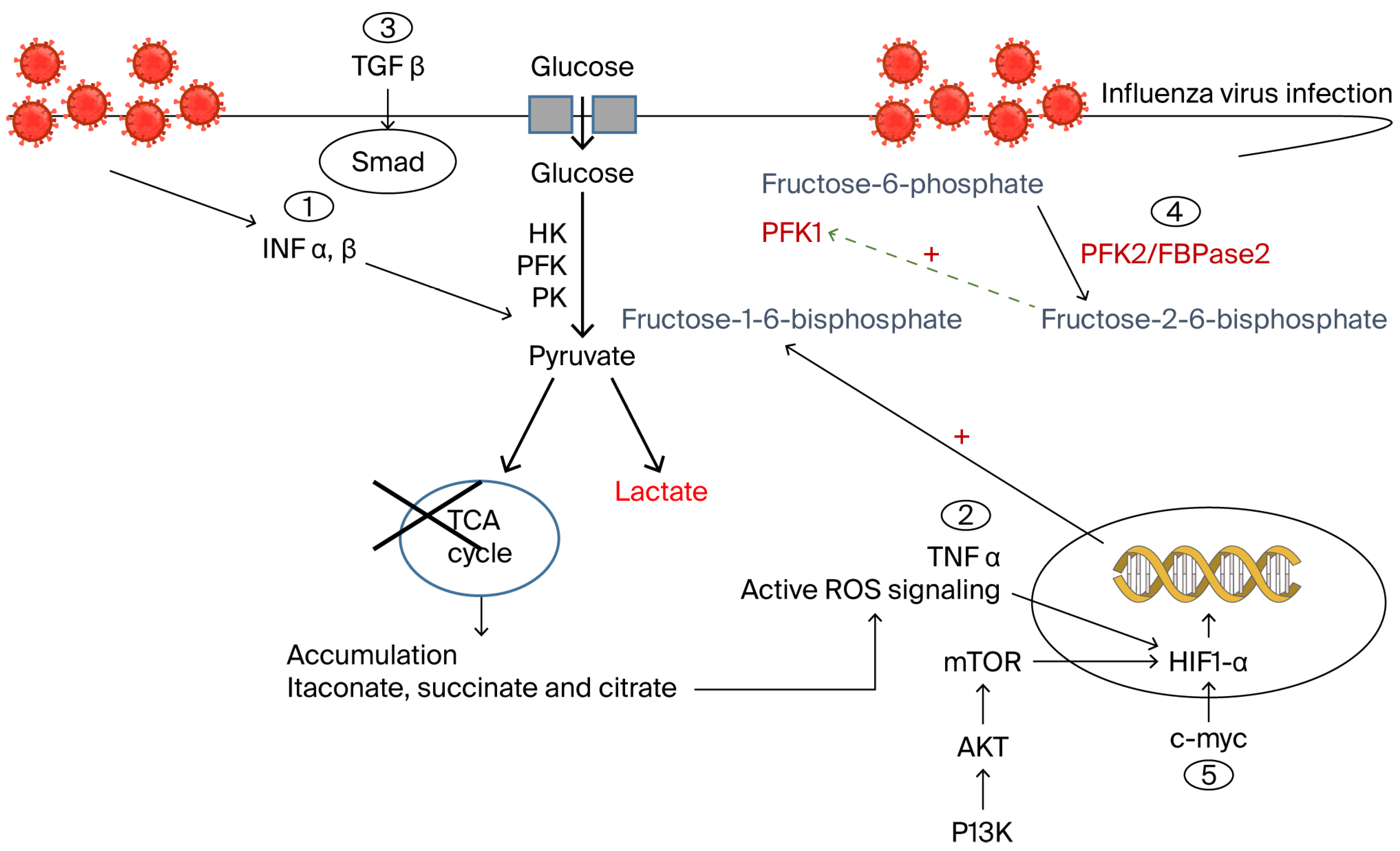

2. Glucose Metabolic Alterations During Influenza Viral Infection

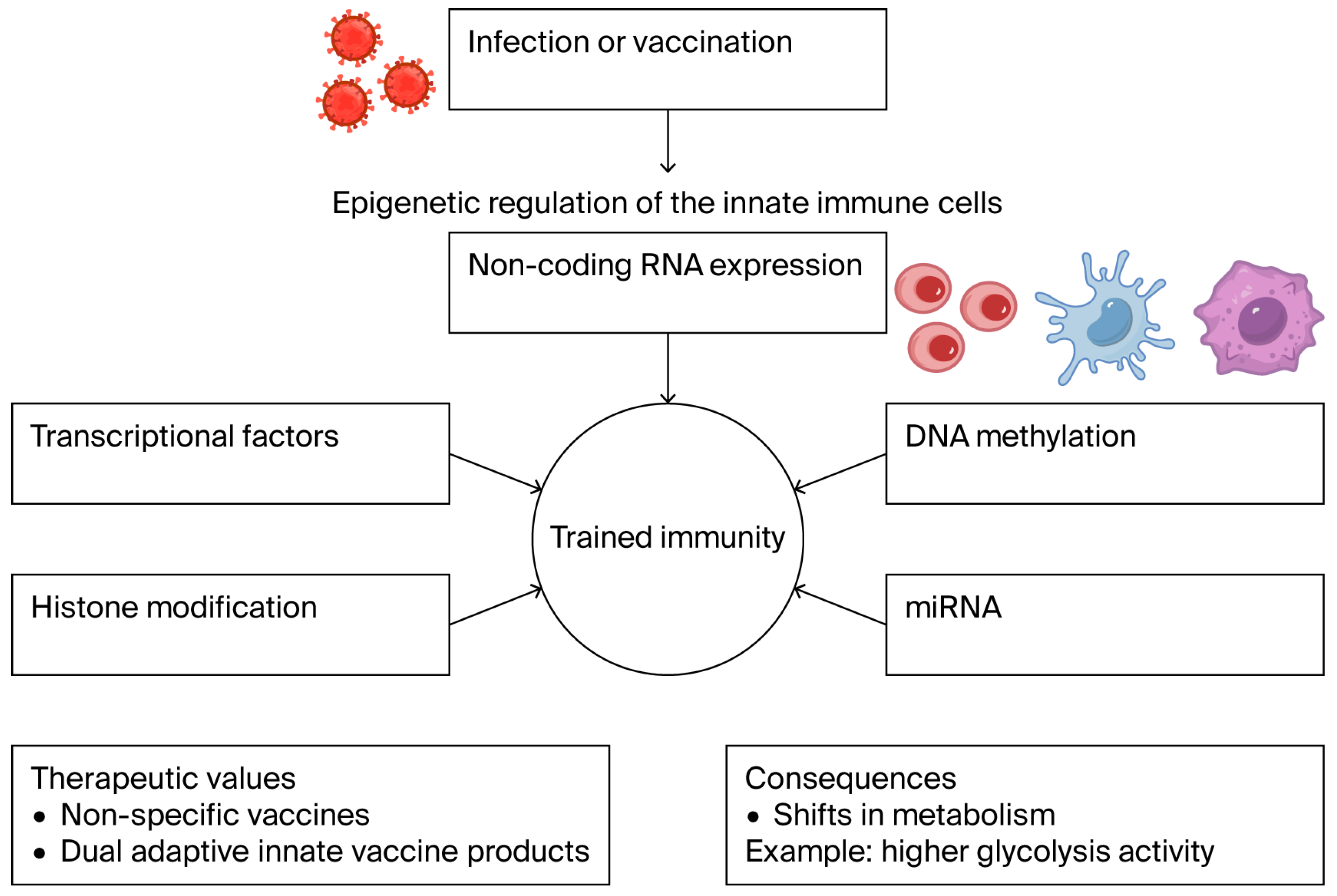

2.1. Influenza Virus-Driven Glucose Metabolic Reprogramming in Immune Cells

2.2. Immune Cell Adaptation to Metabolic Signaling

2.3. Clinical Insights into Glucose-Dependent Immune Metabolic Reprogramming

2.4. Pharmacological Targeting of Glucose-Dependent Metabolic Reprogramming

| Immune Cell Type | Metabolic Profile | Metabolic Mechanism | Influenza Alteration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophages [20,27,48] | M1 | Reduced TCA cycle Increased glycolysis [19,20,27] | PI3K/mTOR inhibition [33,49,51] HIF-1α stabilization [31,40] Induction of resolution [47] GAPDH inhibition [48] c-Myc involvement [41] | Dominated glycolysis “Warburg effect” [20,48] |

| M2 | Reduced TCA cycle Reduced glycolysis [20,27] | Dominated glycolysis [20,48] | ||

| Dendritic cells [41] | Diminished OXPHOS [41,48] | Suppressed OXPHOS Altered glycolysis [41,48] | ||

| Natural killer cells [39,48,49] | Active mTOR [39,48,49] | Inhibited mTOR [39,48,49] | ||

| T-cells/B-cells [40,48,49] | Normal glycolysis [48] | Inhibited glycolysis Increased OXPHOS [40,49] | ||

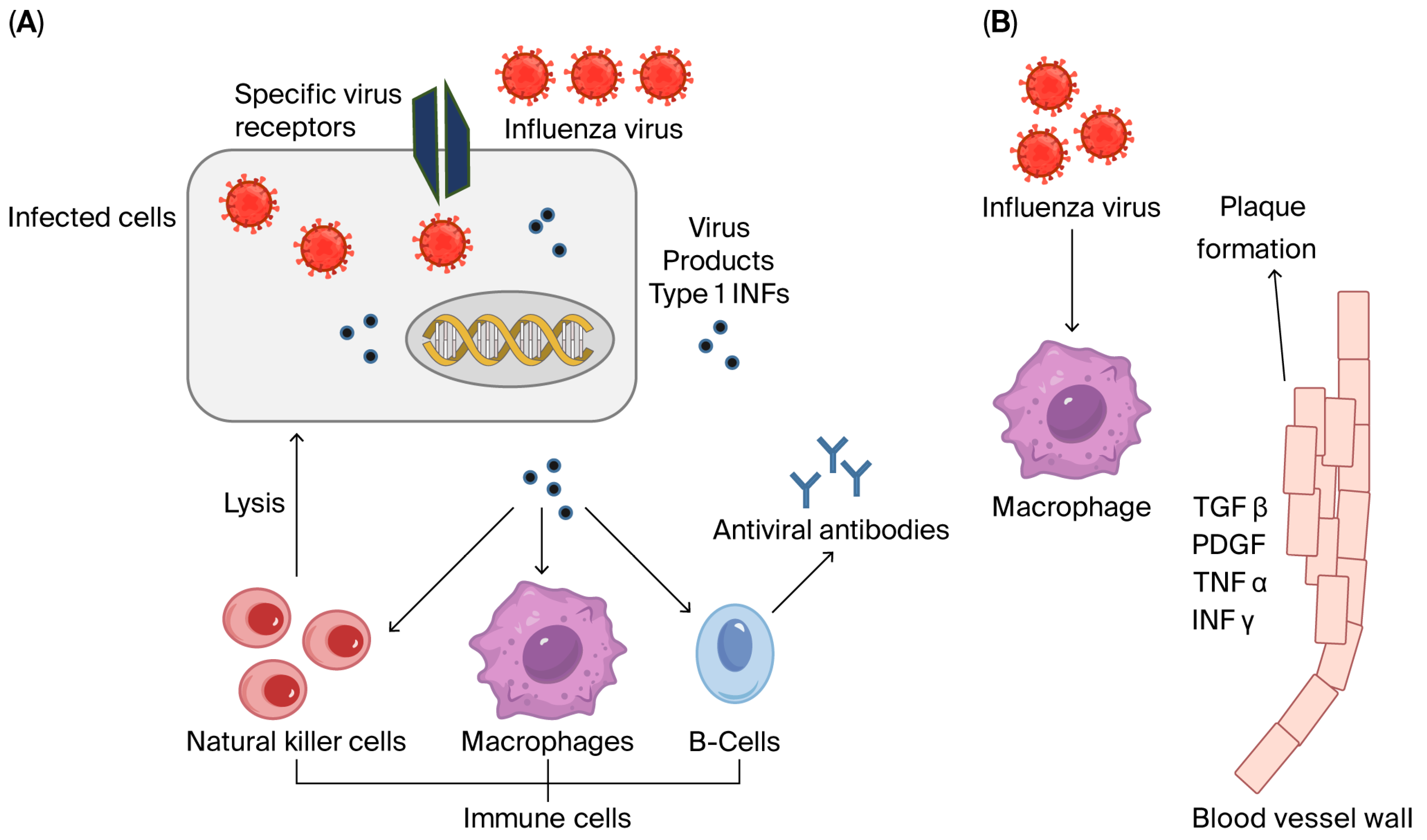

3. Cellular Immune Responses During Influenza Viral Infection

3.1. Inflammatory Cytokines

3.2. Interferons

3.3. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α)

3.4. Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-β1)

3.5. Toll-like Receptors (TLRs)

4. Current Perspectives and Suggested Future Research Directions

4.1. Targeting Metabolic Checkpoints

4.2. Kinases as Dual Metabolic–Immune Regulators

4.3. Integrating Metabolomics and Immunotherapy in Influenza Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Julkunen, I.; Ikonen, N.; Strengell, M.; Ziegler, T. Influenza viruses—A challenge for vaccinations. Duodecim 2012, 128, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, K.D.; Gallo, L.A.; Short, K.R. Influenza Virus and Glycemic Variability in Diabetes: A Killer Combination? Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momajadi, L.; Khanahmad, H.; Mahnam, K. Designing a multi-epitope influenza vaccine: An immunoinformatics approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuBakar, U.; Amrani, L.; Kamarulzaman, F.A.; Karsani, S.A.; Hassandarvish, P.; Khairat, J.E. Avian Influenza Virus Tropism in Humans. Viruses 2023, 15, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousogianni, E.; Perlepe, G.; Boutlas, S.; Rapti, G.; Gouta, E.; Mpaltopoulou, E.; Papagiannis, D.; Exadaktylos, A.; Gourgoulianis, K.; Rouka, E. Clinical features and outcomes of viral respiratory infections in adults during the 2023-2024 winter season. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, N.; Renjen, P.N.; Mahmood, M.A.; Goswami, A.; Chaudhari, D.M. Influenza triggered myositis in an elderly patient: An atypical presentation of influenza infection. J. Neuroimmunol. 2025, 409, 578765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khoury, G.; Hajjar, C.; Geitani, R.; Karam Sarkis, D.; Butel, M.; Barbut, F.; Abifadel, M.; Kapel, N. Gut microbiota and viral respir-atory infections: Microbial alterations, immune modulation, and impact on disease severity: A narrative review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1605143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Feng, H.; Jin, J.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y. Clinical characteristics of influenza pneumonia in patients with lung adenocarcinoma receiving immunotherapy. Viral Immunol. 2025, 38, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianevski, A.; Zusinaite, E.; Kuivanen, S.; Strand, M.; Lysvand, H.; Teppor, M.; Kakkola, L.; Paavilainen, H.; Laajala, M.; Kallio-Kokko, H.; et al. Novel activities of safe-in-human broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Antivir. Res. 2018, 154, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, A.; Ende, Z.; Mishina, M.; Wang, Y.; Falls, Z.; Samudrala, R.; Pohl, J.; Knight, P.; et al. Antiviral approaches against influenza virus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 36, e0004022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, F.; Shindo, N. Influenza virus polymerase inhibitors in clinical development. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 32, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuurman, A.; Rizzo, C.; Haag, M. Investigating the procurement system for understanding seasonal influenza vaccine brand availability in Europe. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamayoshi, S.; Kawaoka, Y. Current and future influenza vaccines. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tregoning, J.; Russell, R.; Kinnear, E. Adjuvanted influenza vaccines. Hum. Vaccine. Immunother. 2018, 14, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.B.; Vanherwegen, A.S.; Eelen, G.; Gutiérrez, A.C.F.; Van Lommel, L.; Marchal, K.; Verlinden, L.; Verstuyf, A.; Nogueira, T.; Georgiadou, M.; et al. Vitamin D3 Induces Tolerance in Human Dendritic Cells by Activation of Intracellular Metabolic Pathways. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, X.; Tian, X.; Ding, S.; Gao, G.; Zhao, X.; Cui, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, H. Metabolic Hostile Takeover: How Influenza Virus Reprograms Cellular Metabolism for Replication. Viruses 2025, 17, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Bai, C.; Zhu, J.; Su, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Qin, X.; Gu, X.; Liu, T. Pharmacological mechanisms of Ma Xing Shi Gan Decoction in treating influenza virus-induced pneumonia: Intestinal microbiota and pulmonary glycolysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1404021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçais, A.; Cherfils-Vicini, J.; Viant, C.; Degouve, S.; Viel, S.; Fenis, A.; Rabilloud, J.; Mayol, K.; Tavares, A.; Bienvenu, J.; et al. The metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR is essential for IL-15 signaling during the development and activation of NK cells. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.K.; Shahin, N.N.; Awad, K.; Maghraby, A.S.; Abd-Elshafy, D.N.; Bahgat, M.M. Glycolytic and immunological alterations in human U937 monocytes in response to H1N1 infection. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 2481–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Maghraby, A.S.; Abd-Elshafy, D.N.; Bahgat, M.M. Carbohydrates metabolic signatures in immune cells: Response to infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 912899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J.B.; Wahl, A.S.; Freund, S.; Genzel, Y.; Reichl, U. Metabolic effects of influenza virus infection in cultured animal cells: Intra- and extracellular metabolite profiling. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010, 4, 4–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camps, J.; Iftimie, S.; Jiménez-Franco, A.; Castro, A.; Joven, J. Metabolic Reprogramming in Respiratory Viral Infections: A Focus on SARS-CoV-2, Influenza, and Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q. Metabolism-associated protein network constructing and host-directed anti-influenza drug repurposing. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Niu, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, L.; Wu, R. The bittersweet link between glucose metabolism, cellular microenvironment and viral infection. Virulence 2025, 16, 2554302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawi, T.K.; Shahin, N.N.; Maghraby, A.S.; Kirschfink, M.; Nadeem Abd-Elshafy, D.; Awad, K.; Bahgat, M.M. H1N1 infection reduces glucose level in human U937 monocytes culture. Viral Immunol. 2020, 33, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugsten, H.R.; Lipka, A.K.; Enersen, A.K.; Nieminen, M.A.; Søland, T.M.; Haug, T.M.; Galtung, H. Metabolic changes in oral fibroblasts after exposure to bacterial extracellular vesicles from three strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Cell. Microbiol. 2025, 2025, 75151004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, M.; Sekiya, T.; Nomura, N.; Daito, T.; Shingai, M.; Kida, H. Influenza virus infection affects insulin signaling, fatty acid-metabolizing enzyme expressions, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle in mice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shi, H.; Sun, M.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Q.; Guo, P.; Cao, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, X.; Li, E.; et al. PFKFB3-driven macrophage glycolytic metabolism is a crucial component of innate antiviral defense. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 2880–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocemba, K.; Dulińska-Litewka, J.; Wojdyła, K.; Pękala, P. The role of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFK-2)/fructose 2, 6-bisphosphatase (FBPase-2) in metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells. Postep. Hig. Med. Dosw. 2016, 70, 938–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Prados, J.-C.; Través, P.G.; Cuenca, J.; Rico, D.; Aragonés, J.; Martín-Sanz, P.; Cascante, M.; Boscá, L. Substrate Fate in Activated Macrophages: A Comparison between Innate, Classic, and Alternative Activation. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, Z.; Li, X.; Meng, R.; Wu, X.; Ding, J.; Shen, W.; Zhu, J. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha promotes macrophage functional activities in protecting hypoxia-tolerant large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) against Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1410082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ling, X.; Yuan, B.; Tao, J. Luteolin-7-O-glucoside promotes macrophage release of IFN-beta by maintaining mitochondrial function and corrects the disorder of glucose metabolism during RSV infection. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 963, 176271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Liu, Q.; Tikoo, S.; Babiuk, L.A.; Zhou, Y. Effect of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway on influenza A virus propagation. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah, R.; Gindlhuber, J.; Heinemann, A. Succinate in innate immunity: Linking metabolic reprogramming to immune modu-lation. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1661948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.M.; Kim, J.J.; Yoo, J.; Kim, K.S.; Gu, Y.; Eom, J.; Jeong, H.; Kim, K.; Nam, K.T.; Park, Y.S.; et al. The interferon-inducible protein viperin controls cancer metabolic reprogramming to enhance cancer progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e157302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, E.B.; Kim, B.; Kim, Y.E.; Na, S.J.; Han, S.M.; Woo, S.O.; Choi, H.M.; Moon, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Choi, J.G. Hovenia dulcis Thunb. Honey Exerts Antiviral Effect Against Influenza A Virus Infection Through Mitochondrial Stress-Mediated Enhancement of Innate Immunity. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, A.; Iqbal, A.; Sahini, N.; Chen, F.; Tantawy, M.; Waqas, F.; Winterhoff, M.; Ebensen, T.; Schultz, K.; Geffers, R.; et al. Itaconate and derivatives reduce interferon responses and inflammation in influenza A virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Attri, K.; Liu, C.; Li, L.; Herring, L.; Asara, J.; Lei, Y.; Singh, P.; Gao, C.; et al. O-GlcNAc Transferase Links Glucose Metabolism to MAVS-Mediated Antiviral Innate Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 791–803.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Zhang, B.; Felice, M.; Blazar, B.; Miller, J. mTORC1 Signaling and Metabolism Are Dynamically Regulated during Human NK Cell Maturation and in Adaptive NK Cell Responses to Viral Infection. Blood 2015, 126, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, S.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Bi, Y.; Liu, G. HIF1alpha-Dependent Metabolic Signals Control the Differentiation of Follicular Helper T Cells. Cells 2019, 8, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezinciuc, S.; Bezavada, L.; Bahadoran, A.; Duan, S.; Wang, R.; Lopez-Ferrer, D.; Finkelstein, D.; McGargill, M.; Green, D.; Pasa-Tolic, L.; et al. Dynamic metabolic reprogramming in dendritic cells: An early response to influenza infection that is essential for effector function. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, M.; Ai, H.; Ma, C.; Tong, Q.; Liu, L.; Velkov, T. ARRDC4-mediated glycolysis enhances innate immunity to influenza A virus through fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2512385122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobs, S.; Kolodziejczyk, A.; Adler, L.; Horesh, N.; Botscharnikow, C.; Herzog, E.; Mohapatra, G.; Hejndorf, S.; Hodgetts, R.; Spivak, I.; et al. Lung dendritic-cell metabolism underlies susceptibility to viral infection in diabetes. Nature 2023, 624, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulme, K.D.; Tong, Z.W.M.; Rowntree, L.C.; van de Sandt, C.E.; Ronacher, K.; Grant, E.J.; Dorey, E.S.; Gallo, L.A.; Gras, S.; Kedzierska, K.; et al. Increasing HbA1c is associated with reduced CD8+ T cell functionality in response to influenza virus in a TCR-dependent manner in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, K.; Yan, L.; Marshall, R.; Bloxham, C.; Upton, K.; Hasnain, S.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; Loh, Z.; Ronacher, K.; Chew, K.; et al. High glucose levels increase influenza-associated damage to the pulmonary epithelial-endothelial barrier. Elife 2020, 9, e56907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Meng, X.; Yi, Z.; Wang, R. Influenza A Virus (H1N1) Infection induces glycolysis to facilitate viral replication. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.; Smith, G.; Ruf-Zamojski, F.; Martínez-Romero, C.; Fribourg, M.; Carbajal, E.; Hartmann, B.; Nair, V.; Marjanovic, N.; Monteagudo, P.; et al. Innate immune response to influenza virus at single-cell resolution in human epithelial cells revealed paracrine induction of interferon lambda 1. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00559-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes Dos Reis, L.; Berçot, M.R.; Castelucci, B.G.; Martins, A.J.E.; Castro, G.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M. Immunometabolic signature during respiratory viral infection: A potential target for host-directed therapies. Viruses 2023, 15, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, C.; Perl, A. Therapeutic mTOR blockade in systemic autoimmunity: Implications for antiviral immunity and extension of lifespan. Autoimmun. Rev. 2021, 20, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meineke, R.; Rimmelzwaan, G.; Elbahesh, H. Influenza Virus Infections and Cellular Kinases. Viruses 2019, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, H.; Duan, S.; Morfouace, M.; Rezinciuc, S.; Shulkin, B.; Shelat, A.; Zink, E.; Milasta, S.; Bajracharya, R.; Oluwaseum, A.; et al. Targeting metabolic reprogramming by influenza infection for therapeutic intervention. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1640–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosaki, T.; Hikida, M. Tyrosine kinases and their substrates in B lymphocytes. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 228, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal Singh, S.; Dammeijer, F.; Hendriks, R.W. Role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cells and malignancies. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Jiang, C.; Liu, Y.; Bell, T.; Ma, W.; Ye, Y.; Huang, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Pleiotropic action of novel bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor bgb-3111 in mantle cell lymphoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 18, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, G.; Whyte, D.; Martinez, R.; Hunter, T.; Sudarsanam, S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Sci. 2002, 298, 1912–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, A.; D’Agostino, M.; Afkhami, S.; Jeyanathan, M.; Xing, Z. Resident memory macrophages and trained innate immunity at barrier tissues. eLife 2025, 14, e106549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, Y.; Lagache, S.M.; Schnack, L.; Godfrey, R.; Kahles, F.; Bruemmer, D.; Findeisen, H.M. mTOR-dependent oxidative stress regulates oxLDL-induced trained innate immunity in human monocytes. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3155. [Google Scholar]

- Chebrolu, C.; Artner, D.; Sigmund, A.; Buer, J.; Zamyatina, A.; Kirschning, C. Species and mediator specific TLR4 antagonism in primary human and murine immune cells by βGlcN(1↔1)αGlc based lipid A mimetics. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 67, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Österlund, P.; Westenius, V.; Guo, D.; Poranen, M.; Bamford, D. Efficient inhibition of avian and seasonal influenza a viruses by a virus-specific dicer-substrate small interfering RNA swarm in human monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01916-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Hansen, K.; Del Rio, D.; Flores, D.; Barghash, R.; Kakkola, L.; Julkunen, I.; Awad, K. Insights into covid-19: Perspectives on drug remedies and host cell responses. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, C.; Pierini-Malosse, C.; Rahmani, K.; Valente, M.; Collinet, N.; Bessou, G.; Guerry, C.; Fabregue, M.; Mathieu, S.; Sharkaoui, S.; et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are dispensable or detrimental in murine systemic or respiratory viral infections. Nat. Immunol. 2025, 26, 1962–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awali, S.; Jin, Y.; Duriancik, D.; Rockwell, C. The Nrf2 activator tBHQ inhibits dendritic cell maturation and activation in response to bacterial and viral stimuli. Toxicol. In Vitro 2026, 111, 106169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadoran, A.; Bezavada, L.; Smallwood, H. Fueling influenza and the immune response: Implications for metabolic reprogramming during influenza infection and immunometabolism. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 295, 140–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, T.J. On the doctrine of original antigenic sin. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1960, 104, 572–578. [Google Scholar]

- Nait Mohamed, F.A.; Lingwood, D. Innate immunity and training to subvert original antigenic sin by the humoral immune response. Elife 2025, 14, e106654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinar-García, M.; Vallejo-Bermúdez, I.; Onieva-García, M.; Reina-Alfonso, I.; Llapa-Chino, L.; Álvarez-Heredia, P.; Salcedo, I.; Solana, R.; Pera, A.; Batista-Duharte, A. Epitope Variation in Hemagglutinin and Antibody Responses to Successive A/Victoria A(H1N1) Strains in Young and Older Adults Following Seasonal Influenza Vaccination: A Pilot Study. Vaccines 2025, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monto, A.; Malosh, R.; Petrie, J.; Martin, E. The doctrine of original antigenic sin: Separating good from evil. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1782–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangeti, S.; Falck-Jones, S.; Yu, M.; Österberg, B.; Liu, S.; Asghar, M.; Sondén, K.; Paterson, C.; Whitley, P.; Albert, J.; et al. Human influenza virus infection elicits distinct patterns of monocyte and dendritic cell mobilization in blood and the nasopharynx. Elife 2023, 12, e77345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanishi, J. Expression of cytokines in bacterial and viral infections and their biochemical aspects. J. Biochem. 2000, 127, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigel, J. Writing committee of the World Health Organization consultation on human influenza a/H5: Avian influenza a (H5N1) infection in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuiken, T.; Riteau, B.; Fouchier, R.; Rimmelzwaan, G. Pathogenesis of influenza virus infections: The good, the bad and the ugly. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, Y.; Liang, C.; Limmon, G.V.; Liang, L.; Engelward, B.P.; Ooi, E.E.; Chen, J.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Molecular analysis of serum and bronchoalveolar lavage in a mouse model of influenza reveals markers of disease severity that can be clinically useful in humans. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Ye, C.; Cui, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, S.; Qudus, M.; Afaq, U.; Fan, H.; et al. Senescent cells promote viral infection-associated inflammation and tissue damage through a robust NF-κB pathway. Cell Commun. Signal 2025, 23, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringquist, R.; Bhatia, E.; Chatterjee, P.; Maniar, D.; Fang, Z.; Franz, P.; Kramer, L.; Ghoshal, D.; Sonthi, N.; Downey, E.; et al. An immune-competent lung-on-a-chip for modelling the human severe influenza infection response. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, R. mTOR regulation of glycolytic metabolism in T cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylova, M.; Shaw, R. The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Jia, J.; Arif, A.; Ray, P.; Fox, P. The GAIT system: A gatekeeper of inflammatory gene expression. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall-Clarke, S.; Tasker, L.; Buchatska, O.; Joan, D.; Joanne, P.; Steve, W.; Persephone, B.; David, Z.W. Influenza H2 haemagglutinin activates B cells via a MyD88-dependent pathway. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkelä, S.; Österlund, P.; Westenius, V.; Latvala, S.; Diamond, M.; Gale, M., Jr.; Julkunen, I. RIG-I Signaling Is Essential for Influenza B Virus-Induced Rapid Interferon Gene Expression. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 12014–12025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Abdelhadi, M.; Awad, A. High glucose reduces influenza and parainfluenza virus productivity by altering glyco-lytic pattern in A549 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrarese, R.; Novazzi, F.; Arcari, G.; Genoni, A.; Ferrante, F.D.; Clementi, N.; Messali, S.; Pitrolo, A.; Caccuri, F.; Piralla, A. Expression patterns of interferons and proinflammatory cytokines in the upper respiratory tract of patients infected by different viral pathogens: Correlation with Age and Viral Load. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyrsted, J.; Storgaard, J.; Blay-Cadanet, J.; Heinz, A.; Thielke, A.L.; Crotta, S.; de Paoli, F.; Olagnier, D.; Wack, A.; Hiller, K.; et al. Influenza A induces lactate formation to inhibit type I. iScience 2021, 24, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, K.; Wu, W.; Pang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Yan, X.; Wang, B.; Qiu, J.; Fang, Z. GRP78 exerts antiviral function against influenza A virus infection by activating the IFN/JAK-STAT signaling. Virology 2024, 600, 110249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fang, P.; He, R.; Li, M.; Yu, H.; Zhou, L.; Yi, Y.; Wang, F.; Rong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. O-GlcNAc transferase promotes influenza A virus-induced cytokine storm by targeting interferon regulatory factor-5. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Solaymani-Mohammadi, F.; Namdari, H.; Arjeini, Y.; Mousavi, M.; Rezaei, F. Metabolic host response and therapeutic approaches to influenza infection. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2020, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, H.; Lian, R.; Dou, X.; Li, S.; Xie, J.; Li, X.; Feng, R.; Li, Z. Histone H1.2 Inhibited EMCV Replication through Enhancing MDA5-Mediated IFN-β Signaling Pathway. Viruses 2024, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiyarasu, S.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, D.S.; Bhatia, S.; Dash, S.; Bhat, S.; Khetan, R.; Nagarajan, S. Highly pathogenic avi-an influenza H5N1 virus induces cytokine dysregulation with suppressed maturation of chicken monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 60, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Qi, X.; Ding, M.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zen, K.; Li, X. Pro-inflammatory cytokine dysregulation is associated with novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in primary human macrophages. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matikainen, S.; Sirén, J.; Tissari, J.; Veckman, V.; Pirhonen, J.; Severa, M.; Sun, Q.; Lin, R.; Meri, S.; Uzé, G.; et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha enhances influenza A virus-induced expression of antiviral cytokines by activating RIG-I gene expression. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Kang, D.; Teng, L.; Chen, N.; Zhan, J.; Yu, R.; Wang, Y.; Lu, B. Biosafety and Efficacy Studies of Colchicine-Encapsulated Liposomes for Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2025, 113, e35540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massague, J.; Cheifetz, S.; Laiho, M.; Ralph, D.A.; Weiss, F.M.; Zentella, A. Transforming growth factor-beta. Cancer Surv. 1992, 12, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nurgazieva, D.; Mickley, A.; Moganti, K.; Ming, W.; Ovsyi, I.; Popova, A.; Sachindra, A.K.; Wang, N.; Bieback, K.; Goerdt, S.; et al. TGF-β1, but not bone morphogenetic proteins, activates Smad1/5 pathway in primary human macrophages and induces expression of proatherogenic genes. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Kakkola, L.; Julkunen, I. High Glucose increases lactate and induces the transforming growth factor beta-Smad 1/5 atherogenic pathway in primary human macrophages. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Zhou, H. Overexpression of chicken IRF7 increased viral replication and programmed cell death to the Avian influenza virus infection through TGF-Beta/FoxO signaling axis in DF-1. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, Q.; Pham, N.; Takada, K.; Ushijima, H.; Komine-Aizawa, S.; Hayakawa, S. Roles of TGF-beta1 in viral Infection during Pregnancy: Research Update and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Chen, F.; Park, H.R.; Han, J.M.; Ji, H.J.; Byun, E.B.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, M.K.; Ahn, K.B.; Seo, H.S. Low-dose radiation therapy sup-presses viral pneumonia by enhancing broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory responses via transforming growth factor-beta production. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1182927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorgen, J.; Dick, J.; Cromarty, R.; Hart, G.; Rhein, J. NK cell subsets and dysfunction during viral infection: A new avenue for therapeutics? Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1267774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denney, L.; Branchett, W.; Gregory, L.; Oliver, R.; Lloyd, C. Epithelial-derived TGF-beta1 acts as a pro-viral factor in the lung during influenza A infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Y.; Bai, X.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Fan, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Sun, L. Influenza A and B virus-triggered epithelial-mesenchymal transition is relevant to the binding ability of NA to latent TGF-beta. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 841462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Ramirez, E.; Ortiz-Stern, A.; Martinez-Mejia, C.; Salinas-Carmona, M.; Rendon, A.; Mata-Tijerina, V.; Rosas-Taraco, A. TGF-beta blood levels distinguish between influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus sepsis and sepsis due to other forms of com-munity-acquired pneumonia. Viral Immunol. 2015, 28, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’neill, L.A.; Golenbock, D.; Bowie, A.G. The history of Toll-like receptors: Redefining innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.; O’Neill, L. Of Flies and Men-The Discovery of TLRs. Cells 2022, 11, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, F.; Zhuang, A.; McQuilten, H.; Jarnicki, A.; O’Donoghue, R.; O’Brien, C.; Ciccotosto, G.; Zhang, P.; Demaison, C.; White, S.; et al. Priming mucosal pathogen-agnostic innate immunity with an intranasal TLR2/6 agonist in an aged population. ERJ Open Res. 2025, 11, 01044–02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, I.; Martinet, W.; Schrijvers, D.M.; Timmermans, J.P.; Bult, H.; De Meyer, G.R. Toll like receptor 7 stimulation by imiquimod induces macrophage autophagy and inflammation in atherosclerotic plaques. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 2012, 107, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.; Giacomassi, C.; Ward, S.; Owen, A.; Luis, T.; Spear, S.; Woollard, K.; Johansson, C.; Strid, J.; Botto, M. TLR7 activation at epithelial barriers promotes emergency myelopoiesis and lung antiviral immunity. Elife 2023, 12, e8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Goffic, R.; Pothlichet Vitour, D.; Fujita, T.; Meurs, E.; Chignard, M.; Si-Tahar, M. Cutting edge: Influenza A virus activates TLR3-dependent inflammatory and RIG-I-dependent antiviral responses in human lung epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 3368–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, H.; Dewald, H.; Rothkopf, Z.; Singh, S.; Jenkins, F.; Deb, P.; De, S.; Barnes, B.; Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P. Frontline Science: AMPK regulates metabolic reprogramming necessary for interferon production in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 109, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchet, W.; Krug, A.; Cella, M.; Newby, C.; Fischer, J.A.; Dzionek, A.; Colonna, M. Dendritic cells respond to influenza virus through TLR7- and PKR-independent pathways. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005, 35, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, K. The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR): Novel Considerations as an Antiviral Treatment. Curr. Neurovasc Res. 2020, 17, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Akira, S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 2005, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, L.; Pearce, E. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, P.K.; Chang, W.A.; Peng, S.Y.; Chu, L.A.; Chuang, Y.H.; Nguyen, L.D.; Guo, J.S.; Wei, H.C.; Lai, P.L.; Chang, H.H.; et al. Endogenous macrophages as “Trojan horses” for targeted oral delivery of mRNA-encoded cytokines in tumor microenvironment im-munotherapy. Biomaterials 2025, 325, 123620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, S.; Mondal, A. Unveiling the role of host kinases at different steps of influenza A virus life cycle. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0119223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.; Artyomov, M. Itaconate: The poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubic, T.; Lametschwandtner, G.; Jost, S.; Hinteregger, S.; Kund, J.; Carballido-Perrig, N.; Schwärzler, C.; Junt, T.; Voshol, H.; Meingassner, J.; et al. Triggering the succinate receptor GPR91 on dendritic cells enhances immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, S.D.; Ramachandran, V.K.; Knudsen, G.M.; Hinton, J.C.; Thompson, A. An incomplete TCA cycle increases survival of Salmonella Typhimurium during infection of resting and activated murine macrophages. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; O’Neill, L. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophages and dendritic cells in innate immunity. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Li, Y.; Uyeda, K.; Hasemann, C. Tissue-specific structure/function differentiation of the liver isoform of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, J.; Abe, Y.; Uyeda, K. Molecular cloning of the DNA and expression and characterization of rat testes fruc-tose-6-phosphate, 2-kinase:fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15764–15770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Garcia, A.; Monsalve, E.; Novellasdemunt, L.; Navarro-Sabaté, A.; Manzano, A.; Rivero, S.; Castrillo, A.; Casado, M.; Laborda, J.; Bartrons, R.; et al. Cooperation of adenosine with macrophage Toll-4 receptor agonists leads to increased glycolytic flux through the enhanced expression of PFKFB3 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 19247–19258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Kam, Y. Insights from Avian Influenza: A Review of Its Multifaceted Nature and Future Pandemic Preparedness. Viruses 2024, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.; Doss, M.; Boland, P.; Tecle, T.; Hartshorn, K. Innate immunity to influenza virus: Implications for future therapy. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 4, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Moki, T.; Takizawa, T.; Shiratsuchi, A.; Nakanishi, Y. Evidence for phagocytosis of influenza virus-infected, apoptotic cells by neutrophils and macrophages in mice. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schughart, K.; Threlkeld, S.C.; Sellers, S.A.; Fischer, W.A., 2nd; Schreiber, J.; Lücke, E.; Heise, M.; Smith, A.M. Analysis of blood proteome in influenza-infected patients reveals new insights into the host response signatures distinguishing mild severe infections. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1693728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Kuba, K.; Neely, G.; Yaghubian-Malhami, R.; Perkmann, T.; Loo, G.; Ermolaeva, M.; Veldhuizen, R.; Leung, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell 2008, 133, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffic, R.L.; Balloy, V.; Lagranderie, M.; Alexopoulou, L.; Escriou, N.; Flavell, R.; Chignard, M.; Si-Tahar, M. Detrimental contribu-tion of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3 to influenza A virus-induced acute pneumonia. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Lee, Y.W.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, S.W.; van Rooijen, N.; Guan, Y.; Seo, S.H. Alveolar macrophages are indispensable for controlling influenza viruses in lungs of pigs. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 4265–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlhoch, C.; Baldinelli, F. Avian influenza, new aspects of an old threat. Eur. Surveill. 2023, 28, 2300227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Averga, S.; Buonomo, B.; Lou, J. Assessing respiratory virus co-infections using an identifiable model: The case of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. J. Theor. Biol. 2026, 616, 112280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, R.; Smith, M.; Holland, L.; Sullins, R.; Holland, S.; Tan, M.; Barrera, G.H.; Thomas, A.; Islas, M.; Kramer, J.; et al. Influenza virus genomic surveillance, Arizona, USA, 2023–2024. Viruses 2023, 16, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, L.; Lima, P.; Archer, S. Macrophage plasticity and glucose metabolism: The role of immunometabolism in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warang, P.; Singh, G.; Moshir, M.; Binazon, O.; Laghlali, G.; Chang, L.; Wouters, H.; Vanhoenacker, P.; Notebaert, M.; Elhemdaoui, N.; et al. Impact of FcRn antagonism on vaccine-induced protective immune responses against viral challenge in COVID-19 and influenza mouse vaccination models. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2025, 21, 2470542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomi, S.; Price, E.; Burgoyne, H.; Faozia, S.; Katahira, E.; McIndoo, E.; Nmaju, A.; Sharma, K.; Aghazadeh-Habashi, A.; Bryant, A.; et al. Omadacycline exhibits anti-inflammatory properties and improves survival in a murine model of post-influenza MRSA pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0046925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, H.; Sanchidrián González, P.M.; Brauny, M.; Labonté, F.M.; Schmitz, C.; Roggan, M.D.; Konda, B.; Hellweg, C.E. Hypoxia Changes Energy Metabolism and Growth Rate in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Awad, K.; Shahin, N.N.; Motawi, T.K.; Abdelhadi, M.; Barghash, R.F.; Awad, A.M.; Kakkola, L.; Julkunen, I. Glucose Metabolism and Innate Immune Responses in Influenza Virus Infection: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives. Cells 2026, 15, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010047

Awad K, Shahin NN, Motawi TK, Abdelhadi M, Barghash RF, Awad AM, Kakkola L, Julkunen I. Glucose Metabolism and Innate Immune Responses in Influenza Virus Infection: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives. Cells. 2026; 15(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwad, Kareem, Nancy N. Shahin, Tarek K. Motawi, Maha Abdelhadi, Reham F. Barghash, Ahmed M. Awad, Laura Kakkola, and Ilkka Julkunen. 2026. "Glucose Metabolism and Innate Immune Responses in Influenza Virus Infection: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives" Cells 15, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010047

APA StyleAwad, K., Shahin, N. N., Motawi, T. K., Abdelhadi, M., Barghash, R. F., Awad, A. M., Kakkola, L., & Julkunen, I. (2026). Glucose Metabolism and Innate Immune Responses in Influenza Virus Infection: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Perspectives. Cells, 15(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells15010047