1. Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies have fundamentally reshaped hematology by enabling the selective targeting of disease-driving cells, signaling pathways, and immune microenvironment components. Since the approval of rituximab in 1997, antibody-based therapy has become integral to the management of both malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorders, ranging from B-cell lymphoma and multiple myeloma to paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, hemophilia A, and immune cytopenia.

Continuous antibody engineering advances, including Fc modification, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), bispecific antibodies, and pH-dependent recycling technologies, have expanded the potency and versatility of antibody therapeutics. These platforms now encompass direct cytotoxic antibodies, payload-delivering ADCs, and T-cell–redirecting bispecific constructs, each with distinct immunologic and mechanistic advantages.

This review summarizes recent progress in therapeutic antibodies for hematologic malignancies and immune-mediated disorders and highlights emerging principles in molecular engineering, structural prediction, and clinical translation. A schematic overview of the major therapeutic antibody classes used in hematology is displayed in

Figure 1.

2. Antibody Therapeutics in Hematologic Malignancies

Therapeutic antibodies are central components of modern treatment strategies for hematological malignancies. A broad antibody modality range, including monoclonal antibodies, ADCs, radioimmunoconjugates, and T-cell-redirecting bispecific antibodies, has received regulatory approval in the United States, Europe, and Japan for the treatment of B-cell lymphomas, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), and multiple myeloma.

Table 1 provides an overview of approved antibody therapeutics and their primary indications.

2.1. B-Cell Malignancies

Antibody therapeutics have transformed the management of B-cell malignancies, beginning with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies and subsequently expanding to include radioimmunoconjugates, next-generation glycoengineered antibodies, and T-cell–redirecting bispecific platforms. Notably, these advances have both improved B-cell lymphoma outcomes and revolutionized B-ALL treatment through CD19-directed T-cell engagement. The following subsections summarize the key developments in CD20-based therapy, emerging CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibodies, and CD19 × CD3 bispecific antibodies for B-ALL.

2.1.1. Anti-CD20 Antibody Evolution

Rituximab marked the beginning of antibody-based treatment for B-cell lymphomas. Nonetheless, intrinsic and acquired resistance, including low CD20 expression, complement resistance, and effector cell exhaustion, have led to the development of next-generation agents. Clinical use of rituximab has revealed resistance mechanisms including trogocytosis-mediated antigen loss, complement exhaustion, and attenuation of Fc-dependent effector functions. These phenomena are increasingly recognized as class effects that may influence the durability of responses to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Obinutuzumab, a glycoengineered type II anti-CD20 antibody, was designed to enhance antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) through afucosylated Fc regions and induce direct non-apoptotic cell death via actin cytoskeleton remodeling [

1]. In the GALLIUM trial, obinutuzumab-based immunochemotherapy demonstrated improved progression-free survival compared to rituximab-based immunochemotherapy in follicular lymphoma, leading to its approval across major regulatory agencies. Ofatumumab, a fully human anti-CD20 antibody, targets a membrane-proximal epitope distinct from that of rituximab and exhibits strong complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). Although its use has declined following the advent of obinutuzumab and targeted therapies for CLL, ofatumumab has provided an important proof-of-concept for epitope engineering in CD20 therapy [

2]. Ibritumomab tiuxetan, a radiolabeled anti-CD20 antibody (90Y-ibritumomab), is an innovative strategy that combines targeted antibody delivery with radioisotopes. Despite its reduced use in the current era, ibritumomab has demonstrated durable responses in indolent B-cell lymphomas and remains an important milestone in antibody–radioconjugate development [

3].

2.1.2. CD20 × CD3 Bispecific Antibodies

The emergence of CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibodies has transformed the treatment paradigms for relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphomas by enabling T-cell engagement independent of native antigen presentation. A pivotal preclinical study by Sun et al. demonstrated that full-length humanized CD20 × CD3 bispecific IgG (CD20-TDB) induces potent T-cell–dependent cytotoxicity against CD20-positive malignant B cells across multiple models [

4]. This molecule strictly activates both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the presence of CD20-expressing targets, mediates perforin/granzyme-dependent killing, and remains effective even when CD20 expression is extremely low or when competing anti-CD20 antibodies, such as rituximab, are present. Notably, CD20-TDB achieved near-complete B cell depletion in humanized and double-transgenic mouse models and showed full activity in cynomolgus monkeys while maintaining IgG-like pharmacokinetics. These mechanistic and translational insights provide a key foundation for the subsequent development of clinically approved CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibodies (BsAbs).

Mosunetuzumab, the first approved CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibody, induces serial T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity and has demonstrated high complete response rates in patients with heavily pretreated follicular lymphoma, including those refractory to anti-CD20 antibodies [

5,

6]. Glofitamab, characterized by a 2:1 CD20:CD3 binding configuration, delivers a highly potent cytotoxic synapse and enables a time-limited treatment course. In relapsed/refractory DLBCL, glofitamab achieves durable remission even after CAR-T failure [

7]. Epcoritamab, a subcutaneously administered CD20 × CD3 antibody, offers comparable efficacy with a more favorable administration profile and reduced cytokine-release-related toxicity, supporting its use in outpatient settings for relapsed/refractory DLBCL [

8] and relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma [

9]. Collectively, these bispecific antibodies represent a new pillar of B-cell lymphoma therapy, complementing CAR-T cells and providing accessible off-the-shelf treatment options for refractory diseases.

2.1.3. Antibody-Based Therapies in B-ALL

Antibody-based immunotherapy has profoundly transformed the treatment paradigm of B-ALL. Two major therapeutic platforms, CD19 × CD3 bispecific T-cell engagers and CD22-directed ADCs, have significantly improved the outcomes in relapsed/refractory (R/R) and minimal residual disease (MRD).

CD19 × CD3 Bispecific Antibody

Blinatumomab, a CD19 × CD3 bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE), activates cytotoxic T cells independently of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction and induces serial killing of CD19-positive leukemic blasts. Clinical studies have demonstrated its transformative impact on multiple diseases. In relapsed/refractory B-ALL, blinatumomab significantly improved overall survival compared with conventional chemotherapy and achieved high complete remission rates, even in heavily pretreated patients [

10]. In MRD-positive B-ALL, blinatumomab induces deep molecular remission, resulting in high rates of MRD negativity and prolonged relapse-free survival [

11]. Emerging evidence indicates that the benefits of blinatumomab extend beyond those for MRD-positive diseases. A recent prospective study in adults with MRD-negative B-ALL demonstrated that consolidation therapy with blinatumomab was safe, reduced the risk of relapse, and yielded excellent long-term survival outcomes [

12]. Notably, the treatment was well tolerated, with low rates of severe cytokine release syndrome or neurotoxicity, underscoring its potential role as a post-remission strategy to deepen and stabilize molecular remission, even in patients who have already achieved MRD negativity.

CD22-Directed Antibody–Drug Conjugate

Inotuzumab ozogamicin (CMC-544) is a humanized anti-CD22 monoclonal antibody that is conjugated to calicheamicin, a highly potent cytotoxic antibiotic. After binding to CD22, the antibody-drug conjugate is rapidly internalized, leading to the intracellular release of calicheamicin. Calicheamicin binds to the minor groove of DNA, inducing double-strand breaks and subsequent apoptosis [

13]. In the pivotal INO-VATE ALL trial for patients with relapsed/refractory B-ALL, inotuzumab ozogamicin demonstrated markedly superior efficacy compared to standard chemotherapy, achieving significantly higher complete remission rates (80.7% vs. 29.4%) and deeper molecular responses, including higher rates of MRD negativity. Veno-occlusive liver disease is the principal treatment-related adverse event associated with inotuzumab ozogamicin [

14].

2.2. Antibody Therapeutics in Multiple Myeloma

The treatment landscape for multiple myeloma (MM) has dramatically evolved with the introduction of monoclonal antibodies targeting plasma cell–specific surface antigens. Foundational reviews, such as those by Yasui et al., emphasize the central role of the immune microenvironment in MM and anticipate the development of immune-based therapeutic approaches [

15]. These early insights have helped frame the subsequent evolution of antibody-directed and T-cell–redirecting therapies that are now central to MM management. In addition to proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, antibody-based therapies have also significantly improved survival outcomes. Currently, clinically approved or investigational antibodies for MM include those targeting CD38, SLAMF7, and BCMA, as well as next-generation bispecific constructs and ADCs.

2.2.1. Anti-CD38 Antibodies

CD38 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that is highly expressed in plasma cells and functions as both a receptor and an ectoenzyme. Daratumumab, the first anti-CD38 antibody approved in 2015, mediates ADCC, CDC, and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis. In addition to immune effector–dependent killing, isatuximab, another anti-CD38 antibody with a distinct epitope and mechanism, can induce direct cytotoxicity. Our recent mechanistic studies have demonstrated that isatuximab triggers direct lysosome-mediated cell death, specifically in MM cells with chromosome 1q gain or amplification (1q+), characterized by FOXM1, NEK2, and UBE2T upregulation [

16]. Moreover, isatuximab promotes internalization into CD38

high cells, leading to lysosomal enlargement and protease-mediated degradation of FOXM1, a transcription factor essential for the proliferation and redox homeostasis of 1q+ MM cells. This process induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and non-apoptotic cell death independent of immune effector cells. Furthermore, combination therapy with pomalidomide or carfilzomib enhanced cytotoxicity by augmenting FOXM1 downregulation and ROS production. Therefore, the FOXM1–NEK2–UBE2T axis is a molecular vulnerability in 1q+ MM and provides a rationale for isatuximab-based regimens targeting high-risk cytogenetic subgroups.

Early mechanistic studies demonstrated that immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), such as lenalidomide, significantly enhance antibody-mediated cytotoxicity by activating natural killer (NK) cells and strengthening ADCC. Foundational studies by Hayashi et al. demonstrated that IMiDs upregulate granzyme B, perforin, and immune synapse formation, thereby potentiating the antitumor efficacy of therapeutic antibodies [

17]. These insights provide a biological basis for clinical regimens such as daratumumab–lenalidomide for multiple myeloma and rituximab–lenalidomide (R

2) for follicular lymphoma, which are now established standards of care.

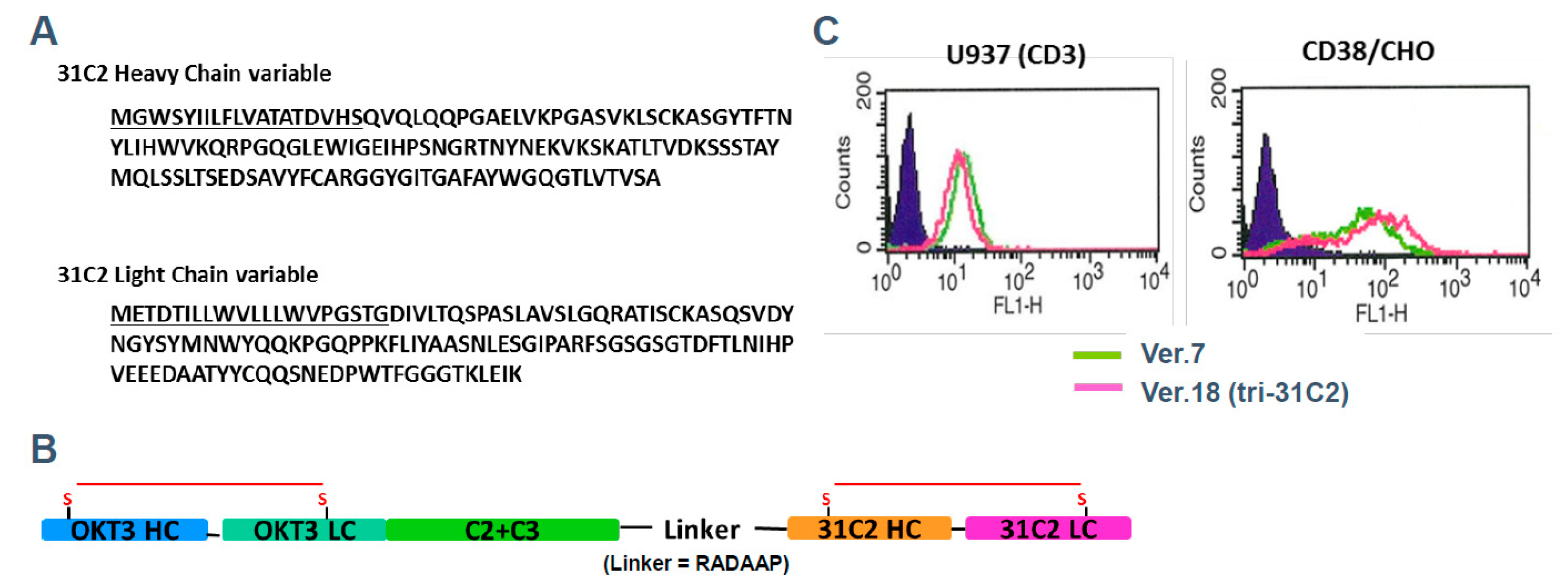

To illustrate the principles of next-generation antibody engineering in multiple myeloma, we refer to a previously reported example of a T-cell–redirecting antibody targeting CD38 and CD3, designated tri-31C2 (

Figure 2) [

18]. This antibody was developed as a conceptual prototype to explore whether simultaneous engagement of tumor-associated antigens and CD3 on T cells could enhance anti-myeloma activity beyond that achieved with conventional monoclonal antibodies. Tri-31C2 was constructed by combining the variable regions of a chimeric anti-CD38 antibody and a humanized anti-CD3 antibody, fused to a human IgG1 Fc region to maintain structural stability and immunoglobulin-like pharmacokinetics. In previously presented studies, this design enabled efficient T-cell engagement and antigen-dependent cytotoxicity against CD38-positive myeloma cells, supporting the feasibility of CD3-redirecting strategies targeting plasma cell antigens (

Figure 3). Importantly, the tri-31C2 example is presented here solely for illustrative purposes, highlighting the conceptual transition from conventional monoclonal antibodies toward multifunctional and T-cell–engaging antibody formats. These early observations anticipated the subsequent clinical success of CD38-directed bispecific antibodies and underscored the potential of rational antibody engineering to amplify antitumor immunity in multiple myeloma.

The functional characterization of tri-31C2, as disclosed in prior scientific presentations, demonstrated enhanced T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity in antigen-dependent coculture systems and xenograft models when compared with a conventional anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody backbone. In the context of this review, the tri-31C2 data are not presented as new experimental results but rather as a representative example illustrating how early antibody engineering efforts informed the development of modern T-cell–redirecting immunotherapies.

2.2.2. Anti-SLAMF7 Antibody

Elotuzumab targets the signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 7 (SLAMF7, also known as CS1), which is encoded on chromosome 1q and is highly expressed in both plasma and NK cells. Its therapeutic efficacy is mainly derived from NK cell activation via SLAMF7–EAT-2 signaling and ADCC against SLAMF7+ myeloma cells.

Our recent molecular analyses have revealed that the soluble form of SLAMF7 (sSLAMF7) is not generated by proteolytic shedding but rather by alternative splicing of the SLAMF7 gene, yielding a unique variant X transcript that lacks the membrane-anchoring exon while preserving both IgV and IgC2 domains [

19]. This variant X encodes a secreted protein that forms homotypic interactions with membrane SLAMF7 and promotes the proliferation of SLAMF7

+ myeloma cells. Its expression level in tumor cells strongly correlates with serum sSLAMF7 concentration, which increases with disease progression. Importantly, elotuzumab neutralizes sSLAMF7, thereby inhibiting its growth-promoting effects.

Beyond direct tumor promotion, sSLAMF7 activates SLAMF7+ macrophages and fosters T-cell exhaustion through SLAMF7-mediated cross-talk, contributing to the immunosuppressive microenvironment of refractory myeloma. sSLAMF7 neutralization by elotuzumab reverses these effects, reducing the abundance of SLAMF7+ regulatory and exhausted T cells, and improving the immune landscape in relapsed/refractory MM. Therefore, high sSLAMF7 or variant X expression may serve as both biomarkers of disease progression and predictive markers of elotuzumab responsiveness, particularly in patients with 1q gain, in which SLAMF7 is upregulated.

Collectively, these findings redefine SLAMF7 as both an immune cell activator and a dual-function antigen in myeloma pathobiology, with its membrane and soluble forms exerting opposing effects that are therapeutically targetable by elotuzumab.

2.2.3. B-Cell Maturation Antigen (BCMA)-Directed Antibodies and Bispecific Constructs

The BCMA is expressed almost exclusively in plasma cells and is a validated target in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Therapeutic modalities include ADCs, BsAbs, and CAR-T cells.

Among the BsAbs, teclistamab and elranatamab redirect T cells to lyse BCMA-positive myeloma cells via CD3 engagement. Contrastingly, belantamab mafodotin is an ADC that delivers a cytotoxic payload through monomethyl auristatin F.

Our recent structure-based study using AlphaFold 3 demonstrated the critical differences in the binding modes of anti-BCMA antibodies to membrane-bound and soluble BCMA. Mutations in the R27–P34 region of BCMA disrupt hydrogen bonding and promote antigen escape, particularly in the R27P and P34del variants [

20]. Furthermore, soluble BCMA (sBCMA), generated by γ-secretase cleavage, exhibits a conformational shift that weakens hydrogen bonds with teclistamab but not with elranatamab or belantamab. Nevertheless, functional assays revealed that teclistamab maintains binding and cytotoxicity even in the presence of sBCMA, suggesting greater resilience to the “sBCMA sink” effect compared to elranatamab or belantamab.

These findings clarify the efficacy of teclistamab in patients previously exposed to BCMA-targeted therapy and provide a structural rationale for the differential antigen escape among BCMA-directed agents.

Collectively, these mechanistic advances highlight the diversity of antibody platforms in MM.

- (1)

CD38 antibodies modulate both immune and intrinsic tumor pathways (FOXM1-driven survival).

- (2)

SLAMF7 antibodies act via NK cell activation and immune synapse enhancement.

- (3)

BCMA antibodies and bispecifics employ structure-optimized binding to overcome antigen escape and soluble antigen interference.

Together, these strategies exemplify how rational antibody engineering and structural prediction are reshaping the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma and expanding the paradigm of precision immunotherapy.

2.2.4. GPRC5D-Directed Antibodies

GPRC5D is an orphan G-protein-coupled receptor highly expressed on malignant plasma cells but minimally detected in normal tissues, except keratinized structures, making it an attractive therapeutic target distinct from BCMA. Talquetamab was the first GPRC5D × CD3 BsAbs to enter clinical practice and has broadened the immunotherapeutic landscape for RRMM.

Talquetamab Monotherapy

Preclinical studies have identified GPRC5D as a promising non-BCMA immunotherapeutic target. GPRC5D is highly expressed in malignant plasma cells, and the GPRC5D × CD3 bispecific antibody, JNJ-64407564, demonstrated potent antigen-specific T-cell–mediated cytotoxicity against myeloma cells in vitro and induced tumor regression in xenograft models [

21].

In clinical phase 1–2 studies, talquetamab exhibited strong and durable responses in heavily pretreated RRMM, including patients previously exposed to BCMA-directed therapies. Overall response rates reached 74%, with ≥very good partial response rates of 59%, and meaningful activity was preserved following prior BCMA CAR-T or BCMA bispecific treatment. Class-specific toxicities, including dysgeusia, skin and nail changes, and cytokine release syndrome (CRS), are generally manageable. Collectively, these findings support GPRC5D as an independent immunotherapeutic axis that enables sequential targeting of plasma cell antigens beyond BCMA [

22].

Dual Targeting of GPRC5D and BCMA

A recent major development is a dual-antigen targeting strategy that combines GPRC5D- and BCMA-directed BsAbs. The phase 1–2 trial demonstrated that talquetamab plus teclistamab achieved an overall response rate and a complete response rate of 80% and 52%, respectively, in heavily pretreated RRMM, with manageable CRS and infection rates and a delayed, attenuated pattern of keratin-related toxicities [

23]. These results provide proof-of-concept that synergistic dual bispecific therapy targeting non-overlapping antigens may overcome antigen escape and broaden the durability of immunotherapy responses.

Clinical Integration

Talquetamab extends the antibody repertoire for RRMM by offering an antigen pathway independent of BCMA and CD38, robust efficacy after BCMA-directed therapy failure, compatibility with dual bispecific approaches (GPRC5D + BCMA), and opportunities for sequential or combination immune targeting. Together with the CD38-, SLAMF7-, and BCMA-focused platforms, talquetamab contributes to the emerging paradigm of multi-antigen, multi-platform immunotherapy in multiple myeloma, enabling more personalized and strategically layered treatment approaches.

2.3. T/NK-Cell and Myeloid Malignancies

Although antibody therapy in T-cell malignancies remains challenging owing to shared antigen expression, emerging targets such as CD30, CCR4, and CD123 have shown promise. Brentuximab vedotin (anti-CD30 ADC) and mogamulizumab (anti-CCR4) have established proof of concept for selective targeting in this difficult category.

2.3.1. Antibody–Drug Conjugates and Targeted Antibodies in T/NK Malignancies

Brentuximab vedotin, an anti-CD30 ADC, has changed the treatment of classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. The AETHERA and ECHELON-2 trials demonstrated their ability to improve progression-free and overall survival when incorporated into frontline or consolidation therapy [

24]. Its success validated the ADC platform for T-cell lymphomas, a historically difficult-to-treat group [

24].

Mogamulizumab, a defucosylated anti-CCR4 antibody developed in Japan, is crucial in adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma (ATLL) [

25], cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, and peripheral T cell lymphomas [

26]. Its enhanced ADCC activity promotes CCR4+ malignant cell selective depletion, and remains among the few effective leukemic ATLL systemic therapies [

25].

Tagraxofusp, a CD123-targeted IL-3 fusion toxin, was the first agent approved for blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm treatment, which is a rare and aggressive malignancy. Although its use is limited, tagraxofusp has demonstrated the feasibility of receptor-directed immunotoxins for the treatment of myeloid neoplasms [

27].

2.3.2. Antibody-Based Therapies in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) is a CD33-directed ADC that delivers the cytotoxic agent calicheamicin to leukemic blasts. Initially approved for relapsed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), GO was temporarily withdrawn due to safety concerns but was subsequently reapproved after evidence from the ALFA-0701 trial demonstrated that fractionated low-dose administration improved both efficacy and safety. Importantly, GO provides clinical benefits mainly in favorable and intermediate-risk AML, often as part of induction chemotherapy. Conversely, its activity in relapsed disease and the risk of hepatic veno-occlusive disease require careful patient selection. Although its role is more limited than that of modern T-cell–redirecting therapies and targeted inhibitors, GO remains a critical example of ADC development in myeloid malignancies.

2.4. Genomic Profiling and Molecular Stratification in Antibody-Based Hematologic Therapy

Genomic profiling expansion in hematologic malignancies has greatly enhanced diagnostic precision, risk stratification, and disease biology understanding. In Japan, the recent insurance approval and nationwide implementation of the HemeSight test marks a major milestone in genomic medicine. HemeSight enables comprehensive detection of single-nucleotide variants, indels, fusion genes, and structural abnormalities across 452 genes via integrated DNA/RNA sequencing of blood or bone marrow samples, with matched normal controls. Although the HemeSight panel has not yet been reported in a peer-reviewed publication, its clinical utility has been demonstrated in a prospective evaluation performed by the National Cancer Center Research Institute, which identified guideline-level actionable abnormalities in 85% of the tested cases.

Nevertheless, the direct link between genomic alterations and the clinical efficacy of antibody-based therapies remains limited. Current therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, including anti-CD20, anti-CD38, anti-SLAMF7, and BCMA-directed agents, are primarily selected based on cell-surface antigen expression and immunophenotyping rather than specific somatic mutations. Gene panel tests are not routinely used to predict therapeutic responses or resistance to antibody therapies. Nonetheless, comprehensive genomic profiling provides a critical foundation for precise immunotherapies. As sequencing approaches evolve toward whole-genome-, whole-exome-, and transcriptome-level analyses, integrative molecular signatures, including antigen expression programs, immune microenvironmental features, clonal architecture, and transcriptional states, are expected to aid in the prediction of antigen escape or downregulation, identification of patients most likely to benefit from bispecific antibodies or CAR-T cell therapy, discovery of resistance pathways associated with chronic antibody exposure, and optimization of rational combination therapies. Although genomic profiling has not yet been directly used to tailor antibody selection, it represents an essential diagnostic and biological platform that will increasingly support precision-guided antibody engineering and immunotherapy strategy development for hematological malignancies.

3. Antibody Therapeutics in Non-Malignant Hematologic Disorders

Further, antibody-based therapies have transformed nonmalignant hematologic disease treatment, including complement-mediated hemolytic disorders, coagulation factor deficiencies, and immune cytopenia. A diverse group of modalities, such as C5 inhibitors, FVIII-mimetic bispecific antibodies, FcRn inhibitors, and selective B-cell–depleting antibodies, is now approved across major regulatory regions.

Table 2 summarizes the currently approved antibody therapeutics for non-malignant hematological conditions and their primary indications.

3.1. Complement Inhibition

Complement inhibition is a landmark in antibody therapeutics [

28]. Eculizumab, a humanized anti-C5 antibody, is the first drug to prevent complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS). Ravulizumab, engineered to have an extended half-life, reduced the infusion frequency from biweekly to every 8 weeks.

Recently, Crovalimab (SKY59), developed using Sequential Monoclonal Antibody Recycling Technology (SMART-Ig), was approved in the USA, EU, Japan, and China for PNH treatment. Crovalimab employs pH-dependent binding and FcRn-mediated recycling, allowing repeated antigen engagement and an extended duration of complement blockade [

29]. Unlike eculizumab and ravulizumab, crovalimab binds a distinct β-chain epitope and remains active in patients with the C5 p.Arg885His polymorphism resistant to eculizumab. The global phase 3 COMMODORE 2 and COMMODORE 3 trials demonstrated crovalimab’s non-inferiority to eculizumab in hemolysis control and transfusion avoidance, with comparable safety profiles [

30]. A pooled safety analysis across COMMODORE 1–3 revealed no meningococcal infections and a lower serious infection rate (8.9 vs. 13.7 per 100 patient-years) compared with eculizumab [

31]. Therefore, crovalimab represents a next-generation C5 inhibitor that combines efficacy, safety, and patient convenience via monthly subcutaneous self-administration.

3.2. Coagulation Disorders

Emicizumab, the first non-factor replacement therapy for hemophilia A, acts as a bispecific FVIIIa-mimetic antibody that bridges activated FIX (FIXa) and FX.

Developed by Chugai and Roche, the two Fab arms of emicizumab simultaneously bind to FIXa and FX to restore tenase complex formation, effectively replicating FVIIIa’s cofactor function [

32]. The binding affinities (KD ≈ 1–2 µM) allow reversible catalytic cycling, ensuring physiological coagulation without excessive thrombin generation. Clinically, emicizumab provides sustained prophylaxis via subcutaneous injection every 1–4 weeks and is effective in patients treated with FVIII inhibitors. Long-term results from the HAVEN 1–4 trials demonstrated an annualized bleeding rate of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1–1.7), with 82% of patients experiencing zero treated bleeds at 144 weeks [

33].

Severe thrombotic or TMA events are rare and limited to cases with concomitant high-dose activated prothrombin complex concentrates.

Thus, emicizumab exemplifies the successful application of antibody engineering to functionally replace a missing coagulation protein, dramatically improving the outcomes and quality of life in patients with hemophilia A.

3.3. Immunodeficiency-Associated CD20-Positive B-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Immunodeficiency-associated CD20-positive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders represent a distinct category of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-driven proliferation arising from impaired immune surveillance, including methotrexate-associated LPD, post-transplant LPD, EBV-positive mucocutaneous ulcers, and other EBV-positive B-cell proliferations. These disorders span a continuum from reactive polyclonal expansion to aggressive B-cell lymphomas with partial reversibility upon immune restoration [

34]. Notably, rituximab is central to EBV-infected CD20 + B cell management, often producing a rapid response. Although rituximab is only formally approved for this indication in Japan, it is widely used off-label worldwide [

35,

36]. Their biology highlights the critical interplay between EBV infection, immune suppression, and B-cell expansion, positioning these disorders at the interface between benign and malignant hematological diseases.

3.4. FcRn Inhibition in Immune Thrombocytopenia

Emerging antibody therapies, such as anti-FcRn antibodies for immune thrombocytopenia and autoimmune hemolytic anemia, are expanding the therapeutic horizons in benign hematology.

The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) regulates IgG homeostasis by protecting IgG from lysosomal degradation via pH-dependent recycling. Disruption of this pathway has emerged as an effective therapeutic strategy for IgG-mediated autoimmune diseases.

Efgartigimod alfa is an engineered human IgG1 Fc fragment with a markedly increased affinity for FcRn at physiological pH. By competitively blocking IgG recycling, efgartigimod accelerates the degradation of pathogenic IgG, leading to a rapid reduction in total IgG levels, including antiplatelet antibodies in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) [

37].

In a phase 3 trial (ADVANCE IV), efgartigimod significantly improved durable platelet responses and reduced bleeding events in patients with chronic ITP refractory to standard therapies [

38], resulting in regulatory approval across the United States, European Union, and Japan. Beyond ITP, FcRn inhibition represents a platform technology with potential applicability to autoimmune hemolytic anemia and other IgG-mediated hematologic disorders. Its safety profile and mechanism of action provide a therapeutic complement to B-cell–directed strategies such as rituximab, underscoring the expanding diversity of antibody-based therapies in benign hematology.

A summary of the major mechanistic classes of therapeutic antibodies used in nonmalignant hematologic disorders, including complement inhibitors, coagulation-modifying antibodies, and FcRn inhibitors, is presented in

Table 3.

4. Future Perspectives

The rapid evolution of therapeutic antibodies in hematology is entering a new phase characterized by multifunctional engineering, T-cell redirection, and structure-guided optimization. While monoclonal antibodies, antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), and bispecific antibodies have dramatically improved outcomes across malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorders, several unresolved clinical challenges remain critical for future development.

One major challenge associated with next-generation bispecific antibodies is treatment-related toxicity, particularly cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), and infectious complications. Sustained T-cell engagement can lead to prolonged immune activation, T-cell exhaustion, and hypogammaglobulinemia, thereby increasing susceptibility to viral, bacterial, and opportunistic infections. Optimizing dosing schedules, step-up strategies, and combination regimens, as well as improving patient selection, will be essential to balance efficacy and safety in real-world practice.

For antibody–drug conjugates, off-target toxicity and payload-related adverse events remain significant limitations. The clinical experience with belantamab mafodotin has highlighted corneal toxicity as a class-specific adverse effect, reflecting antigen expression in non-malignant tissues and intracellular payload release. Future ADC development will require refined linker technologies, optimized payload selection, and improved tumor-specific antigen targeting to enhance the therapeutic window while minimizing systemic toxicity.

Another emerging concern is antigen escape and resistance. Loss of target antigen expression, such as CD19 downregulation after anti-CD19 therapy, as well as amino acid mutations in BCMA or GPRC5D, can reduce antibody binding and compromise treatment efficacy. Recent structural studies have demonstrated that mutations within key epitope regions of BCMA can alter hydrogen bonding and promote immune escape, underscoring the importance of epitope-resilient antibody design. These findings provide a strong rationale for dual-targeting or multi-antigen strategies to prevent clonal selection and prolong response durability [

23].

In this context, combinatorial approaches using bispecific antibodies targeting non-overlapping antigens have shown promising clinical activity. Phase 2 data with extended follow-up demonstrated that dual bispecific therapy with talquetamab (GPRC5D × CD3) and teclistamab (BCMA × CD3) achieved deep and durable responses in heavily pretreated multiple myeloma, including extramedullary disease, with a manageable safety profile [

23]. Furthermore, recent phase 3 evidence indicates that bispecific antibody–based combinations may substantially reshape the treatment landscape. In December 2025, teclistamab combined with daratumumab demonstrated markedly improved progression-free survival and depth of response compared with established daratumumab-based regimens, with predominantly low-grade and manageable cytokine release syndrome, supporting earlier integration of off-the-shelf bispecific antibody combinations with appropriate infection prophylaxis and supportive care [

39].

Beyond antibody engineering itself, advances in artificial intelligence–driven structural prediction, such as AlphaFold 3, are beginning to transform antibody development. These tools enable precise epitope mapping, prediction of antigen escape variants, and rational optimization of antibody–antigen interactions, facilitating the design of next-generation antibodies with improved resilience to mutation and soluble antigen interference.

Finally, integration of genomic and transcriptomic profiling into antibody-based precision medicine represents an important future direction. Although current gene panel testing is primarily used for diagnosis and classification rather than treatment selection, comprehensive molecular profiling may ultimately identify transcriptional programs, antigen expression patterns, and immune microenvironment features that predict response, toxicity, or resistance to antibody therapies. As these technologies mature, the convergence of genomic medicine, structural biology, and immunotherapy is expected to guide patient stratification and rational combination strategies.

Collectively, future antibody therapeutics in hematology will increasingly rely on multi-antigen targeting, toxicity-aware engineering, and structure-guided design, supported by genomic and immunologic insights. These advances are poised to further refine precision immunotherapy and expand the clinical impact of antibody-based treatments across both malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorders.

5. Conclusions

Therapeutic antibodies have profoundly transformed hematologic medicine, enabling the targeted manipulation of malignant and immune pathways with increasing precision. The trajectory from rituximab to glycoengineered CD20 antibodies, radioimmunoconjugates to highly potent CD20 × CD3 bispecifics, and CD38/SLAMF7/BCMA antibodies to structurally optimized bispecific platforms in multiple myeloma illustrates the remarkable breadth of innovation achieved over the past two decades. In benign hematology, the advent of FcRn inhibitors, recycling of C5 antibodies, and FVIII-mimetic bispecifics has further expanded the reach of antibody therapeutics beyond oncology, improving outcomes in ITP, PNH, aHUS, and hemophilia A.

Collectively, these developments highlight a new era in which molecular engineering, structural modeling, and immunological insights converge to shape next-generation antibody therapeutics. As multifunctional designs, AI-assisted antigen prediction, and combination strategies with cellular therapies continue to advance, antibody-based treatments will remain at the forefront of precision medicine for both malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y. and K.I.; methodology, H.Y.; formal analysis, H.Y.; investigation, H.Y. and T.I.; resources, H.Y., M.I. and T.I.; data curation, H.Y. and T.I.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.; writing—review and editing, H.Y., M.I., T.I. and K.I.; visualization, H.Y.; supervision, K.I.; project administration, H.Y.; funding acquisition, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP22H04923, CoBiA; H.Y.) and the Practical Research Project for Rare/Intractable Diseases of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED; Grant Number 25ek0109807JP; H.Y.).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mai Igarashi (Sapporo Medical University) for their technical assistance. We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp, accessed on 23 December 2025) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ADC | antibody–drug conjugate |

| ADCC | antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity |

| aHUS | atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| ALL | acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia |

| ATLL | adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| BiTE | bispecific T-cell engager |

| BsAb | bispecific antibody |

| CAR-T | chimeric antigen receptor T cell |

| CDC | complement-dependent cytotoxicity |

| CLL | chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| CR | complete response |

| CRS | cytokine release syndrome |

| DLBCL | diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| FcRn | neonatal Fc receptor |

| FVIII | factor VIII |

| GPRC5D | G-protein–coupled receptor class C group 5 member D |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| IMiD | immunomodulatory drug |

| ITP | immune thrombocytopenia |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| MM | multiple myeloma |

| MRD | minimal residual disease |

| NK cell | natural killer cell |

| ORR | overall response rate |

| PBMC | peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| PNH | paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria |

| R/R | relapsed or refractory |

| RRMM | relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SLAMF7 | signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 7 |

| sBCMA | soluble B-cell maturation antigen |

| sSLAMF7 | soluble SLAMF7 |

| TMA | thrombotic microangiopathy |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Alduaij, W.; Ivanov, A.; Honeychurch, J.; Cheadle, E.J.; Potluri, S.; Lim, S.H.; Shimada, K.; Chan, C.H.; Tutt, A.; Beers, S.A.; et al. Novel type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (GA101) evokes homotypic adhesion and actin-dependent, lysosome-mediated cell death in B-cell malignancies. Blood 2011, 117, 4519–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wierda, W.G.; Kipps, T.J.; Mayer, J.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Williams, C.D.; Hellmann, A.; Robak, T.; Furman, R.R.; Hillmen, P.; Trneny, M.; et al. Ofatumumab as single-agent CD20 immunotherapy in fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzig, T.E.; Gordon, L.I.; Cabanillas, F.; Czuczman, M.S.; Emmanouilides, C.; Joyce, R.; Pohlman, B.L.; Bartlett, N.L.; Wiseman, G.A.; Padre, N.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of yttrium-90-labeled ibritumomab tiuxetan radioimmunotherapy versus rituximab immunotherapy for patients with relapsed or refractory low-grade, follicular, or transformed B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 2453–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.L.; Ellerman, D.; Mathieu, M.; Hristopoulos, M.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, X.; Clark, R.; Reyes, A.; Stefanich, E.; et al. Anti-CD20/CD3 T cell-dependent bispecific antibody for the treatment of B cell malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 287ra270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, L.E.; Sehn, L.H.; Matasar, M.; Schuster, S.J.; Assouline, S.; Giri, P.; Kuruvilla, J.; Canales, M.; Dietrich, S.; Fay, K.; et al. Safety and efficacy of mosunetuzumab, a bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehn, L.H.; Bartlett, N.L.; Matasar, M.J.; Schuster, S.J.; Assouline, S.E.; Giri, P.; Kuruvilla, J.; Shadman, M.; Cheah, C.Y.; Dietrich, S.; et al. Long-term 3-year follow-up of mosunetuzumab in relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma after ≥2 prior therapies. Blood 2025, 145, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, M.J.; Carlo-Stella, C.; Morschhauser, F.; Bachy, E.; Corradini, P.; Iacoboni, G.; Khan, C.; Wrobel, T.; Offner, F.; Trneny, M.; et al. Glofitamab for Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieblemont, C.; Karimi, Y.H.; Ghesquieres, H.; Cheah, C.Y.; Clausen, M.R.; Cunningham, D.; Jurczak, W.; Do, Y.R.; Gasiorowski, R.; Lewis, D.J.; et al. Epcoritamab in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma: 2-year follow-up from the pivotal EPCORE NHL-1 trial. Leukemia 2024, 38, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, K.M.; Vitolo, U.; Jurczak, W.; Lugtenburg, P.J.; Gyan, E.; Sureda, A.; Christensen, J.H.; Hess, B.; Tilly, H.; Cordoba, R.; et al. Epcoritamab monotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (EPCORE NHL-1): A phase 2 cohort of a single-arm, multicentre study. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e593–e605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarjian, H.; Stein, A.; Gokbuget, N.; Fielding, A.K.; Schuh, A.C.; Ribera, J.M.; Wei, A.; Dombret, H.; Foa, R.; Bassan, R.; et al. Blinatumomab versus Chemotherapy for Advanced Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokbuget, N.; Dombret, H.; Bonifacio, M.; Reichle, A.; Graux, C.; Faul, C.; Diedrich, H.; Topp, M.S.; Bruggemann, M.; Horst, H.A.; et al. Blinatumomab for minimal residual disease in adults with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2018, 131, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzow, M.R.; Sun, Z.; Mattison, R.J.; Paietta, E.M.; Roberts, K.G.; Zhang, Y.; Racevskis, J.; Lazarus, H.M.; Rowe, J.M.; Arber, D.A.; et al. Blinatumomab for MRD-Negative Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiJoseph, J.F.; Armellino, D.C.; Boghaert, E.R.; Khandke, K.; Dougher, M.M.; Sridharan, L.; Kunz, A.; Hamann, P.R.; Gorovits, B.; Udata, C.; et al. Antibody-targeted chemotherapy with CMC-544: A CD22-targeted immunoconjugate of calicheamicin for the treatment of B-lymphoid malignancies. Blood 2004, 103, 1807–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Stelljes, M.; Martinelli, G.; Liedtke, M.; Stock, W.; Gokbuget, N.; O’Brien, S.; Wang, K.; Wang, T.; et al. Inotuzumab Ozogamicin versus Standard Therapy for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, H.; Ishida, T.; Maruyama, R.; Nojima, M.; Ikeda, H.; Suzuki, H.; Hayashi, T.; Shinomura, Y.; Imai, K. Model of translational cancer research in multiple myeloma. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, J.; Osada, N.; Matsuoka, S.; Ohta, T.; Kazama, H.; Shirai, H.; Meloni, M.; Chiron, M.; Yasui, H.; Nakasone, H.; et al. FOXM1 down-regulation is a trigger of isatuximab-induced direct cell death in multiple myeloma cells with 1q. Haematologica, 2025; Early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Hideshima, T.; Akiyama, M.; Podar, K.; Yasui, H.; Raje, N.; Kumar, S.; Chauhan, D.; Treon, S.P.; Richardson, P.; et al. Molecular mechanisms whereby immunomodulatory drugs activate natural killer cells: Clinical application. Br. J. Haematol. 2005, 128, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Yasui, H.; Ishiguro, K.; Aoki, Y.; Ikeda, H. The Trifunctional Antibody (tri-31C2) Targeting CD38 and CD3 Has a Stronger Anti-Myeloma Effect Than the Chimeric Anti-CD38 Monoclonal Antibody (ch-31C2). In Proceedings of the 58th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition, San Diego, CA, USA, 2 December 2016; p. 2097. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, J.; Hori, M.; Osada, N.; Matsuoka, S.; Suzuki, A.; Kakugawa, S.; Yasui, H.; Harada, T.; Tenshin, H.; Abe, M.; et al. Soluble SLAMF7 is generated by alternative splicing in multiple myeloma cells. Haematologica 2024, 109, 3414–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, J.; Osada, N.; Matsuoka, S.; Yasui, H.; Furukawa, Y.; Nakasone, H. Structure-based prediction reveals a difference in the binding mode of anti-BCMA antibodies to BCMA and soluble BCMA. Leukemia 2025, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillarisetti, K.; Edavettal, S.; Mendonca, M.; Li, Y.; Tornetta, M.; Babich, A.; Majewski, N.; Husovsky, M.; Reeves, D.; Walsh, E.; et al. A T-cell-redirecting bispecific G-protein-coupled receptor class 5 member D x CD3 antibody to treat multiple myeloma. Blood 2020, 135, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chari, A.; Touzeau, C.; Schinke, C.; Minnema, M.C.; Berdeja, J.G.; Oriol, A.; van de Donk, N.; Rodriguez-Otero, P.; Morillo, D.; Martinez-Chamorro, C.; et al. Safety and activity of talquetamab in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MonumenTAL-1): A multicentre, open-label, phase 1–2 study. Lancet Haematol. 2025, 12, e269–e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.C.; Magen, H.; Gatt, M.; Sebag, M.; Kim, K.; Min, C.K.; Ocio, E.M.; Yoon, S.S.; Chu, M.P.; Rodriguez-Otero, P.; et al. Talquetamab plus Teclistamab in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, S.; O’Connor, O.A.; Pro, B.; Illidge, T.; Fanale, M.; Advani, R.; Bartlett, N.L.; Christensen, J.H.; Morschhauser, F.; Domingo-Domenech, E.; et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): A global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, T.; Joh, T.; Uike, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Utsunomiya, A.; Yoshida, S.; Saburi, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Takemoto, S.; Suzushima, H.; et al. Defucosylated anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody (KW-0761) for relapsed adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma: A multicenter phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, M.; Ishida, T.; Hatake, K.; Taniwaki, M.; Ando, K.; Tobinai, K.; Fujimoto, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Uike, N.; et al. Multicenter phase II study of mogamulizumab (KW-0761), a defucosylated anti-cc chemokine receptor 4 antibody, in patients with relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemmaraju, N.; Lane, A.A.; Sweet, K.L.; Stein, A.S.; Vasu, S.; Blum, W.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Wang, E.S.; Duvic, M.; Sloan, J.M.; et al. Tagraxofusp in Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic-Cell Neoplasm. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, R.; Luzzatto, L. Breakthrough Hemolysis in PNH with Proximal or Terminal Complement Inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuzawa, T.; Sampei, Z.; Haraya, K.; Ruike, Y.; Shida-Kawazoe, M.; Shimizu, Y.; Gan, S.W.; Irie, M.; Tsuboi, Y.; Tai, H.; et al. Long lasting neutralization of C5 by SKY59, a novel recycling antibody, is a potential therapy for complement-mediated diseases. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, A.; He, G.; Tong, H.; Lin, Z.; Wang, X.; Chai-Adisaksopha, C.; Lee, J.H.; Brodsky, A.; Hantaweepant, C.; Dumagay, T.E.; et al. Phase 3 randomized COMMODORE 2 trial: Crovalimab versus eculizumab in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria naive to complement inhibition. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 1768–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, A.; Fu, R.; He, G.; Alzahrani, H.; Chou, S.C.; Hicheri, Y.; Kazmierczak, M.; Recova, V.L.; Uchiyama, M.; Vladareanu, A.M.; et al. Safety of Crovalimab Versus Eculizumab in Patients with Paroxysmal Nocturnal Haemoglobinuria (PNH): Pooled Results from the Phase 3 COMMODORE Studies. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025, 114, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitazawa, T.; Esaki, K.; Tachibana, T.; Ishii, S.; Soeda, T.; Muto, A.; Kawabe, Y.; Igawa, T.; Tsunoda, H.; Nogami, K.; et al. Factor VIIIa-mimetic cofactor activity of a bispecific antibody to factors IX/IXa and X/Xa, emicizumab, depends on its ability to bridge the antigens. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, M.U.; Negrier, C.; Paz-Priel, I.; Chang, T.; Chebon, S.; Lehle, M.; Mahlangu, J.; Young, G.; Kruse-Jarres, R.; Mancuso, M.E.; et al. Long-term outcomes with emicizumab prophylaxis for hemophilia A with or without FVIII inhibitors from the HAVEN 1-4 studies. Blood 2021, 137, 2231–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaggio, R.; Amador, C.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Attygalle, A.D.; Araujo, I.B.O.; Berti, E.; Bhagat, G.; Borges, A.M.; Boyer, D.; Calaminici, M.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquet, S.; Leblond, V.; Herbrecht, R.; Socie, G.; Stoppa, A.M.; Vandenberghe, P.; Fischer, A.; Morschhauser, F.; Salles, G.; Feremans, W.; et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab in B-cell post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: Results of a prospective multicenter phase 2 study. Blood 2006, 107, 3053–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atallah-Yunes, S.A.; Salman, O.; Robertson, M.J. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder: Update on treatment and novel therapies. Br. J. Haematol. 2023, 201, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrichts, P.; Guglietta, A.; Dreier, T.; van Bragt, T.; Hanssens, V.; Hofman, E.; Vankerckhoven, B.; Verheesen, P.; Ongenae, N.; Lykhopiy, V.; et al. Neonatal Fc receptor antagonist efgartigimod safely and sustainably reduces IgGs in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 4372–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broome, C.M.; McDonald, V.; Miyakawa, Y.; Carpenedo, M.; Kuter, D.J.; Al-Samkari, H.; Bussel, J.B.; Godar, M.; Ayguasanosa, J.; De Beuf, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the neonatal Fc receptor inhibitor efgartigimod in adults with primary immune thrombocytopenia (ADVANCE IV): A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 1648–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.J.; Bahlis, N.J.; Perrot, A.; Nooka, A.K.; Lu, J.; Pawlyn, C.; Mina, R.; Caeiro, G.; Kentos, A.; Hungria, V.; et al. Teclistamab plus Daratumumab in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |