Comparing a Novel Anti-BCMA NanoCAR with a Conventional ScFv-Based CAR for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma

Highlights

- A novel Nb17-based BCMA nanoCAR-T was successfully engineered and displayed in vitro cytotoxicity, cytokine release, and transcriptomic profiles comparable to the clinically validated scFv-CAR CT103a.

- Nb17-nanoCAR-T showed potent antitumor activity in vivo, fully eradicating myeloma tumors similarly to CT103a.

- Single-domain antibody-based CARs can achieve efficacy equivalent to conventional scFv-CAR-T, supporting their use as viable therapeutic alternatives in multiple myeloma.

- The Nb17-nanoCAR-T design highlights the potential of VHH-based CARs for future development of more stable, compact, and potentially less immunogenic cell therapies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Primary T Cells

2.2. PBMCs and T Cells Isolation

2.3. Lentiviral Vector Production and Cell Transduction

2.4. Flow Cytometry Staining and Analysis

2.5. Quantification of BCMA or CAR Cell Surface Expressions and Binding Capacity of VHH Nb17

2.6. Cellular Cytotoxicity Assays and CAR-T Phenotyping and Characterization: Flow Cytometry

2.7. CD107a Degranulation Assays: Flow Cytometry

2.8. Cellular Cytotoxicity Assays and Cytokine Productions: ELISA

2.9. Bulk-RNA Sequencing

2.10. In Vivo NSG Mouse Model

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

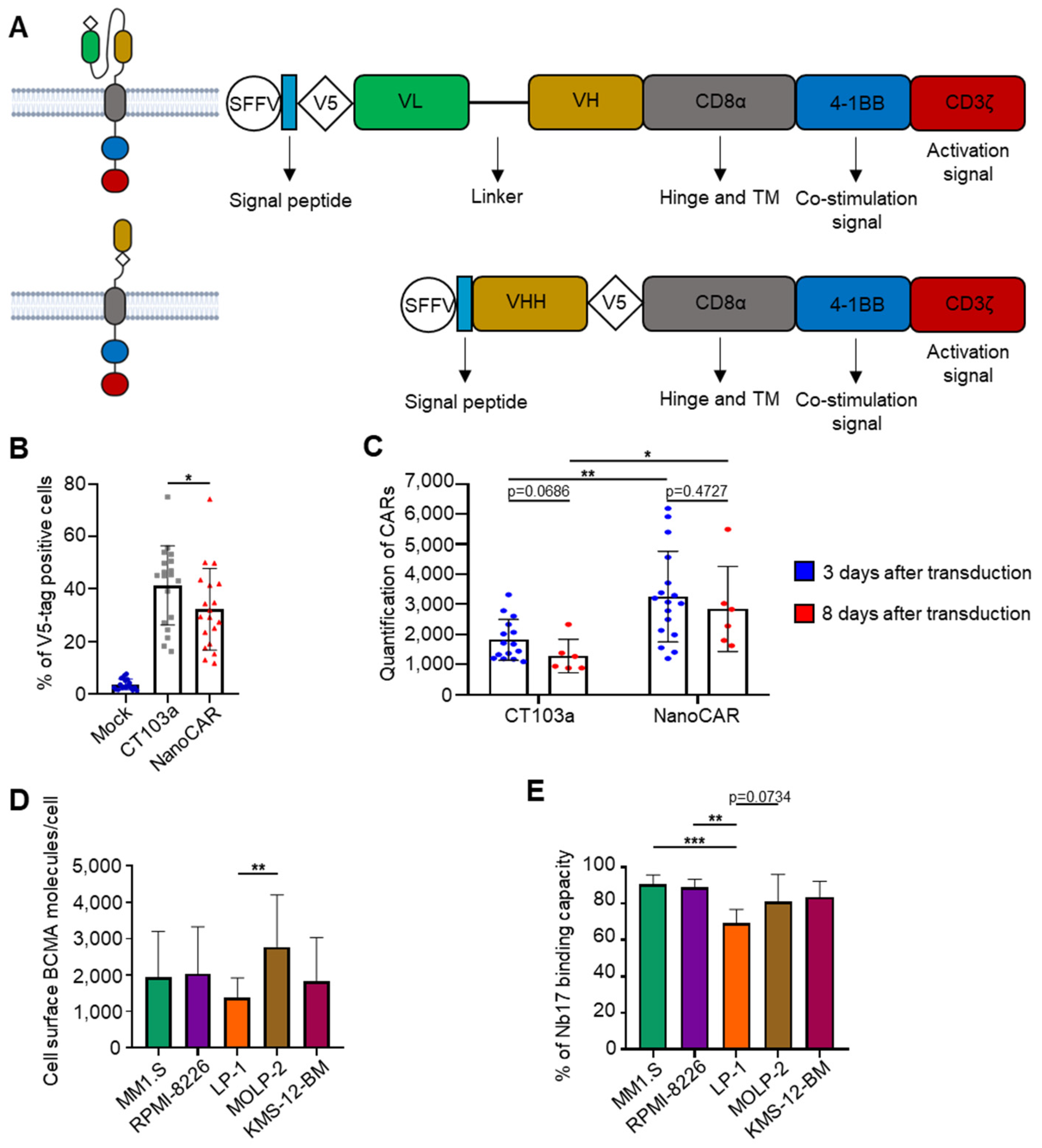

3.1. Construction of a nanoCAR Sequence Containing VHH Nb17

3.2. In Vitro Efficacy of CT103a and nanoCAR in Killing BCMA+ MM Cell Lines

3.3. Persistence of CAR-T Killing Ability Following Repeated Antigen Challenges

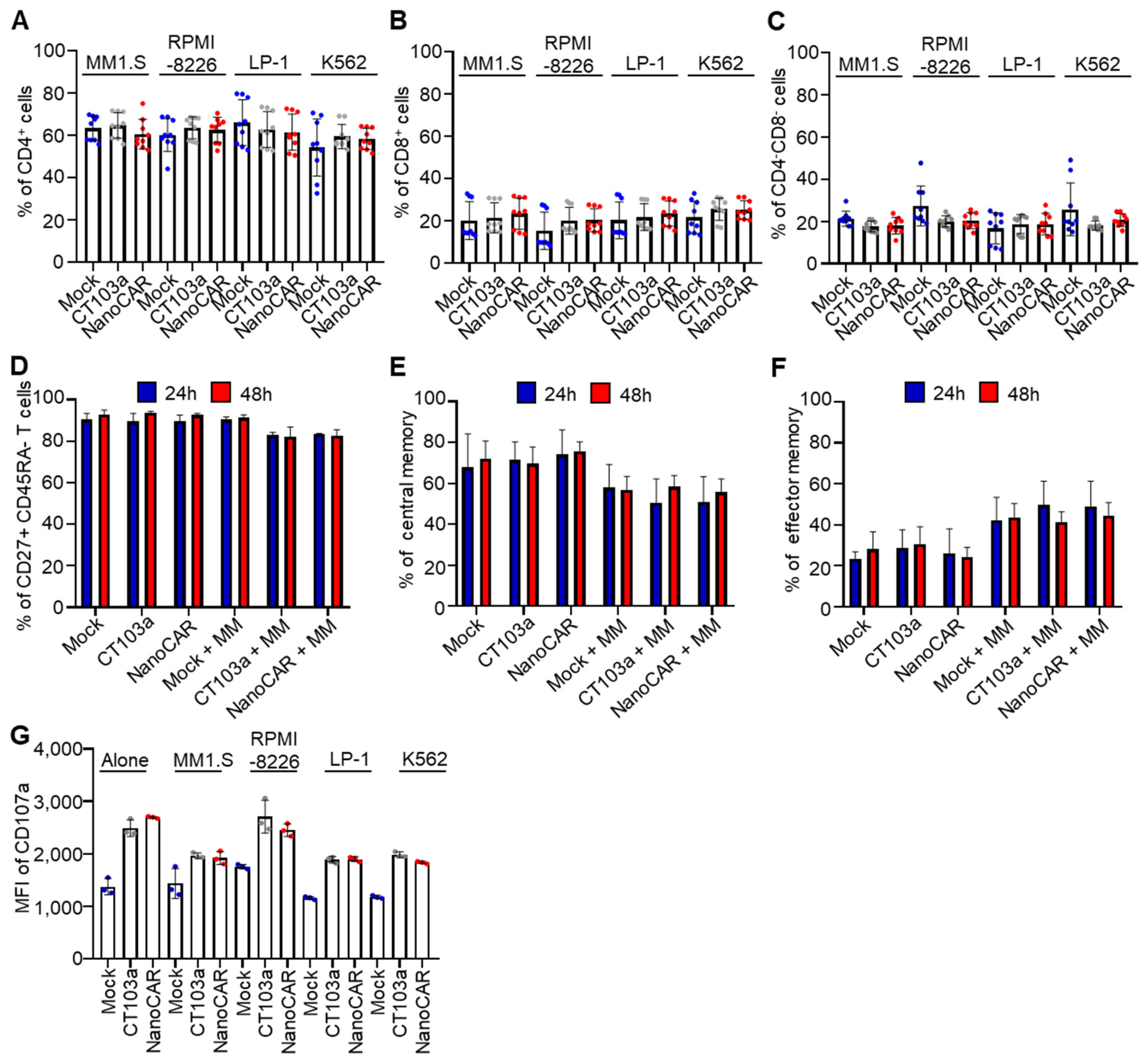

3.4. CAR-T-Cell Differentiation into Central Memory Subsets with Enhanced CD107a Surface Expression

3.5. CT103a and nanoCAR Produce Cytokines When Co-Cultured with MM Cell Lines

3.6. Gene Expression Studies of CT103a and nanoCAR Co-Cultured with MM Cells

3.7. CT103a and nanoCAR Can Eliminate Tumor Cell In Vivo

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| BCMA | B-cell maturation antigen |

| BM | Bone marrow |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| Cilta-cel | Ciltacabtagene autoleucel |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| ScFv | Single-chain variable fragment |

| SdAb | Single domain antibody |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TCM | Central memory T cell |

| TEM | Effector memory T cell |

| VHH | Heavy chain variable domains |

References

- Laubach, J.; Richardson, P.; Anderson, K. Multiple Myeloma. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Went, M.; Duran-Lozano, L.; Halldorsson, G.H.; Gunnell, A.; Ugidos-Damboriena, N.; Law, P.; Ekdahl, L.; Sud, A.; Thorleifsson, G.; Thodberg, M.; et al. Deciphering the genetics and mechanisms of predisposition to multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, K.C.; Davis, J.A.; Cendagorta, A.; Granger, K.; Gaffney, K.J.; Green, K.; Hess, B.T.; Hashmi, H. “Fast but not so furious”: A condensed step-up dosing schedule of teclistamab for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. eJHaem 2024, 5, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Richter, J. Management of Toxicities Associated with BCMA, GPRC5D, and FcRH5-Targeting Bispecific Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma. Curr. Hematol. Malign-Rep. 2024, 19, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedan, S.; Ruella, M.; June, C.H. Emerging Cellular Therapies for Cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 37, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkarsh, K.; Srivastava, N.; Kumar, S.; Khan, A.; Dagar, G.; Kumar, M.; Singh, M.; Haque, S. CAR-T cell therapy: A game-changer in cancer treatment and beyond. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 1300–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association for Cancer Research. First-Ever CAR T-cell Therapy Approved in U.S. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, S.; Lin, Y.; Goldschmidt, H.; Reece, D.; Nooka, A.; Senin, A.; Rodriguez-Otero, P.; Powles, R.; Matsue, K.; Shah, N.; et al. KarMMa-RW: Comparison of idecabtagene vicleucel with real-world outcomes in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Long, X.; Cai, H.; Chen, C.; Hu, G.; Lou, Y.; Xing, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Xiao, M.; et al. A Model Perspective Explanation of the Long-Term Sustainability of a Fully Human BCMA-Targeting CAR (CT103A) T-Cell Immunotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 803693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Que, Y.; Ding, S.; Hu, G.; Wang, W.; Mao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, L.; Zhou, J.; et al. Anti-BCMA CAR-T cells therapy for a patient with extremely high membrane BCMA expression: A case report. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Melenhorst, J.J. CT103A, a forward step in multiple myeloma immunotherapies. Blood Sci. 2021, 3, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wei, R.; Guo, S.; Min, C.; Zhong, X.; Huang, H.; Cheng, Z. An alternative fully human anti-BCMA CAR-T shows response for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma with anti-BCMA CAR-T exposures previously. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 31, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, D.; Song, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, J.; Dong, Y.; Hu, K.; Liu, P.; et al. CT103A, a novel fully human BCMA-targeting CAR-T cells, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Updated results of phase 1b/2 study (FUMANBA-1). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 8025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampusch, M.S.; Haran, K.P.; Hart, G.T.; Rakasz, E.G.; Rendahl, A.K.; Berger, E.A.; Connick, E.; Skinner, P.J. Rapid Transduction and Expansion of Transduced T Cells with Maintenance of Central Memory Populations. Mol. Ther.-Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.W.; Prochazkova, M.; Shao, L.; Traynor, R.; Underwood, S.; Black, M.; Fellowes, V.; Shi, R.; Pouzolles, M.; Chou, H.-C.; et al. CAR-T cell expansion platforms yield distinct T cell differentiation states. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, L.D.M.; Barros, L.R.C.; Viegas, M.S.; Marques, L.V.C.; Ferreira, P.D.S.; Chicaybam, L.; Bonamino, M.H. Development of CAR-T cell therapy for B-ALL using a point-of-care approach. OncoImmunology 2020, 9, 1752592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyldermans, S. Nanobodies: Natural Single-Domain Antibodies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 775–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brilhante-Da-Silva, N.; Sousa, R.M.D.O.; Arruda, A.; dos Santos, E.L.; Marinho, A.C.M.; Stabeli, R.G.; Fernandes, C.F.C.; Pereira, S.D.S. Camelid Single-Domain Antibodies for the Development of Potent Diagnosis Platforms. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2021, 25, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duray, E.; Lejeune, M.; Baron, F.; Beguin, Y.; Devoogdt, N.; Krasniqi, A.; Lauwers, Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; D’hUyvetter, M.; Dumoulin, M.; et al. A non-internalised CD38-binding radiolabelled single-domain antibody fragment to monitor and treat multiple myeloma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, E.C.; Shiferaw, M.Y.; Admasu, F.T.; Dejenie, T.A. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel: The second anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapeutic armamentarium of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 991092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Bringing cell therapy to tumors: Considerations for optimal CAR binder design. Antib. Ther. 2023, 6, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssens, H.; Meeus, F.; Gesquiere, E.L.; Puttemans, J.; De Vlaeminck, Y.; De Veirman, K.; Breckpot, K.; Devoogdt, N. Anti-Idiotypic VHHs and VHH-CAR-T Cells to Tackle Multiple Myeloma: Different Applications Call for Different Antigen-Binding Moieties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, G.; Yang, Y.; Meng, G.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y.; Niu, P. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) Binding to BCMA, and Uses Thereof. US20200376030A1, 3 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L.; Fang, X.; Xu, C. Single Domain Antibodies and Chimeric Antigen Receptors Targeting BCMA and Methods of Use Thereof. WO2021121228A1, 24 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Guo, S.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Liu, Q.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.; Yuan, Z.; et al. A 33-residue peptide tag increases solubility and stability of Escherichia coli produced single-chain antibody fragments. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghal, M.; Matte, K.; Venes, A.; Patel, S.; Laroche, G.; Sarvan, S.; Joshi, M.; Rain, J.-C.; Couture, J.-F.; Giguère, P.M. Development of a V5-tag–directed nanobody and its implementation as an intracellular biosensor of GPCR signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beghein, E.; Gettemans, J. Nanobody Technology: A Versatile Toolkit for Microscopic Imaging, Protein–Protein Interaction Analysis, and Protein Function Exploration. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Cervantes-Contreras, F.; Lee, S.Y.; Green, D.J.; Till, B.G. Improved Expansion and Function of CAR T Cell Products from Cultures Initiated at Defined CD4:CD8 Ratios. Blood 2018, 132, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, F.; Kozani, P.S.; Rahbarizadeh, F. T-cells engineered with a novel VHH-based chimeric antigen receptor against CD19 exhibit comparable tumoricidal efficacy to their FMC63-based counterparts. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1063838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Ge, T.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Y.; Mu, W.; Cai, H.; Dai, Z.; Jin, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. Preclinical development and evaluation of nanobody-based CD70-specific CAR T cells for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 2331–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Wang, H.; Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Lin, G.; Jiang, P. The development of chimeric antigen receptor T-cells against CD70 for renal cell carcinoma treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssens, H.; Meeus, F.; De Vlaeminck, Y.; Lecocq, Q.; Puttemans, J.; Debie, P.; De Groof, T.W.M.; Goyvaerts, C.; De Veirman, K.; Breckpot, K.; et al. Scrutiny of chimeric antigen receptor activation by the extracellular domain: Experience with single domain antibodies targeting multiple myeloma cells highlights the need for case-by-case optimization. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1389018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, W.C.; Nix, M.A.; Naik, A.; Izgutdina, A.; Huang, B.J.; Wicaksono, G.; Phojanakong, P.; Serrano, J.A.C.; Young, E.P.; Ramos, E.; et al. Framework humanization optimizes potency of anti-CD72 nanobody CAR-T cells for B-cell malignancies. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Munter, S.; Ingels, J.; Goetgeluk, G.; Bonte, S.; Pille, M.; Weening, K.; Kerre, T.; Abken, H.; Vandekerckhove, B. Nanobody Based Dual Specific CARs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, S.L.; Frey, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Aplenc, R.; Barrett, D.M.; Bunin, N.J.; Chew, A.; Gonzalez, V.E.; Zheng, Z.; Lacey, S.F.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1507–1517, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 998. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMx160005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, R.A.; Finney, O.; Annesley, C.; Brakke, H.; Summers, C.; Leger, K.; Bleakley, M.; Brown, C.; Mgebroff, S.; Kelly-Spratt, K.S.; et al. Intent-to-treat leukemia remission by CD19 CAR T cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood 2017, 129, 3322–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, J.W.; Bhattarai, N. CAR-T Cell Therapy: Mechanism, Management, and Mitigation of Inflammatory Toxicities. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 693016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.A.; Covassin, L.; Brehm, M.A.; Racki, W.; Pearson, T.; Leif, J.; Laning, J.; Fodor, W.; Foreman, O.; Burzenski, L.; et al. Human peripheral blood leucocyte non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain gene mouse model of xenogeneic graft-versus-host-like disease and the role of host major histocompatibility complex. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 157, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covassin, L.; Laning, J.; Abdi, R.; Langevin, D.L.; Phillips, N.E.; Shultz, L.D.; Brehm, M.A. Human peripheral blood CD4 T cell-engrafted non-obese diabetic-scid IL2rγ null H2-Ab1 tm1Gru Tg (human leucocyte antigen D-related 4) mice: A mouse model of human allogeneic graft-versus-host disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2011, 166, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Luo, Q.; Li, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Shao, B.; Hong, Y.; Tan, T.; Dong, X.; et al. Development of novel humanized CD19/BAFFR bicistronic chimeric antigen receptor T cells with potent antitumor activity against B-cell lineage neoplasms. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 205, 1361–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Lin, K.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, W.; et al. Nanobody-derived bispecific CAR-T cell therapy enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of T cell lymphoma treatment. Mol. Ther.-Oncolytics 2023, 30, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kueberuwa, G.; Gornall, H.; Alcantar-Orozco, E.M.; Bouvier, D.; Kapacee, Z.A.; Hawkins, R.E.; Gilham, D.E. CCR7+ selected gene-modified T cells maintain a central memory phenotype and display enhanced persistence in peripheral blood in vivo. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jassin, M.; Onkelinx, C.; Bocuzzi, V.; E Silva, B.; Kwan, O.; Block, A.; Dubois, S.; Daulne, C.; Marcion, G.; Ormenese, S.; et al. Comparing a Novel Anti-BCMA NanoCAR with a Conventional ScFv-Based CAR for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2025, 14, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241944

Jassin M, Onkelinx C, Bocuzzi V, E Silva B, Kwan O, Block A, Dubois S, Daulne C, Marcion G, Ormenese S, et al. Comparing a Novel Anti-BCMA NanoCAR with a Conventional ScFv-Based CAR for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241944

Chicago/Turabian StyleJassin, Mégane, Chloé Onkelinx, Valentina Bocuzzi, Bianca E Silva, Oswin Kwan, Alix Block, Sophie Dubois, Coline Daulne, Guillaume Marcion, Sandra Ormenese, and et al. 2025. "Comparing a Novel Anti-BCMA NanoCAR with a Conventional ScFv-Based CAR for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma" Cells 14, no. 24: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241944

APA StyleJassin, M., Onkelinx, C., Bocuzzi, V., E Silva, B., Kwan, O., Block, A., Dubois, S., Daulne, C., Marcion, G., Ormenese, S., Di Valentin, E., Baron, F., Grégoire, C., Ehx, G., Nguyen, T. T., & Caers, J. (2025). Comparing a Novel Anti-BCMA NanoCAR with a Conventional ScFv-Based CAR for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Cells, 14(24), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241944