Regulation of CLK1 Isoform Expression by Alternative Splicing in Activated Human Monocytes Contributes to Activation-Associated TNF Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. RNA Extraction and Sequencing: Short-Read and Oxford Nanopore Long-Read RNA-Seq

2.3. Short-Read RNA-Seq Pipeline

2.4. Oxford Nanopore Long-Read RNA Pipeline

2.5. Analyzing CLK1 RNA Expression Using Real-Time PCR

2.6. Analyzing CLK1 Protein Expression Using Western Blot

2.7. Inhibitors Used to Study RNA Dynamics and Functional Effects

2.8. Flow Cytometry

2.9. Statistics

3. Results

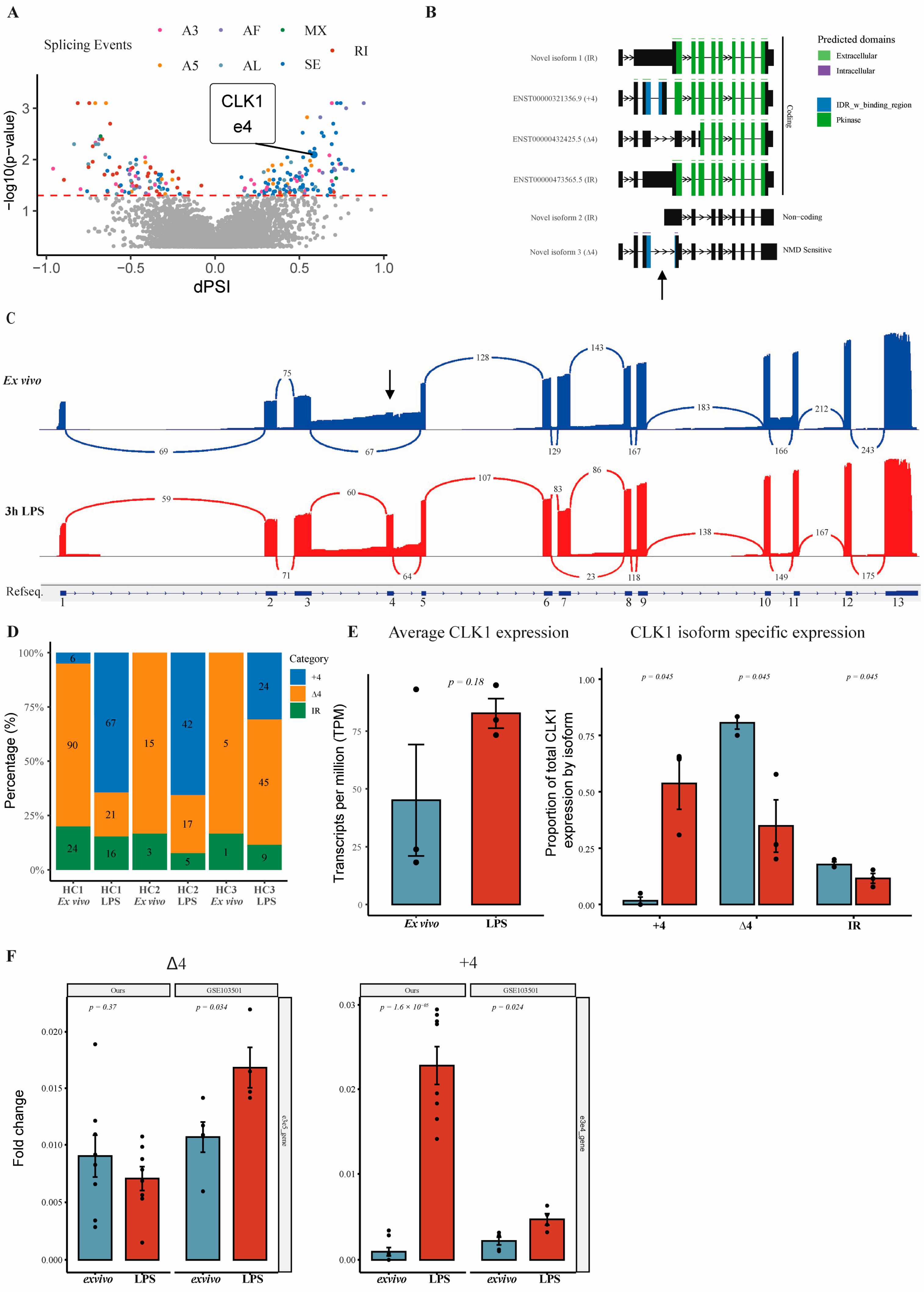

3.1. Identification and Characterization of CLK1 Isoforms in Human Monocytes

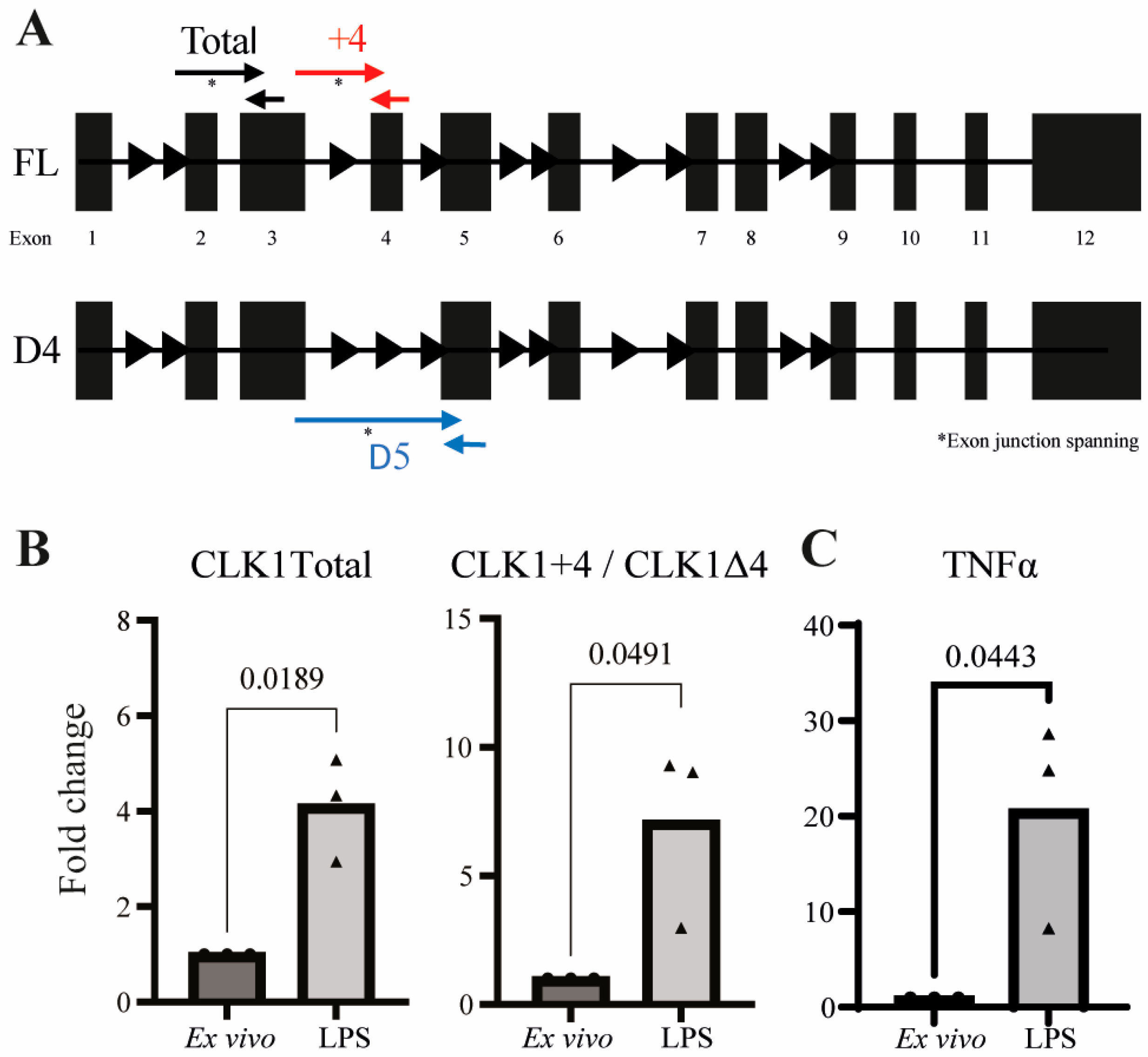

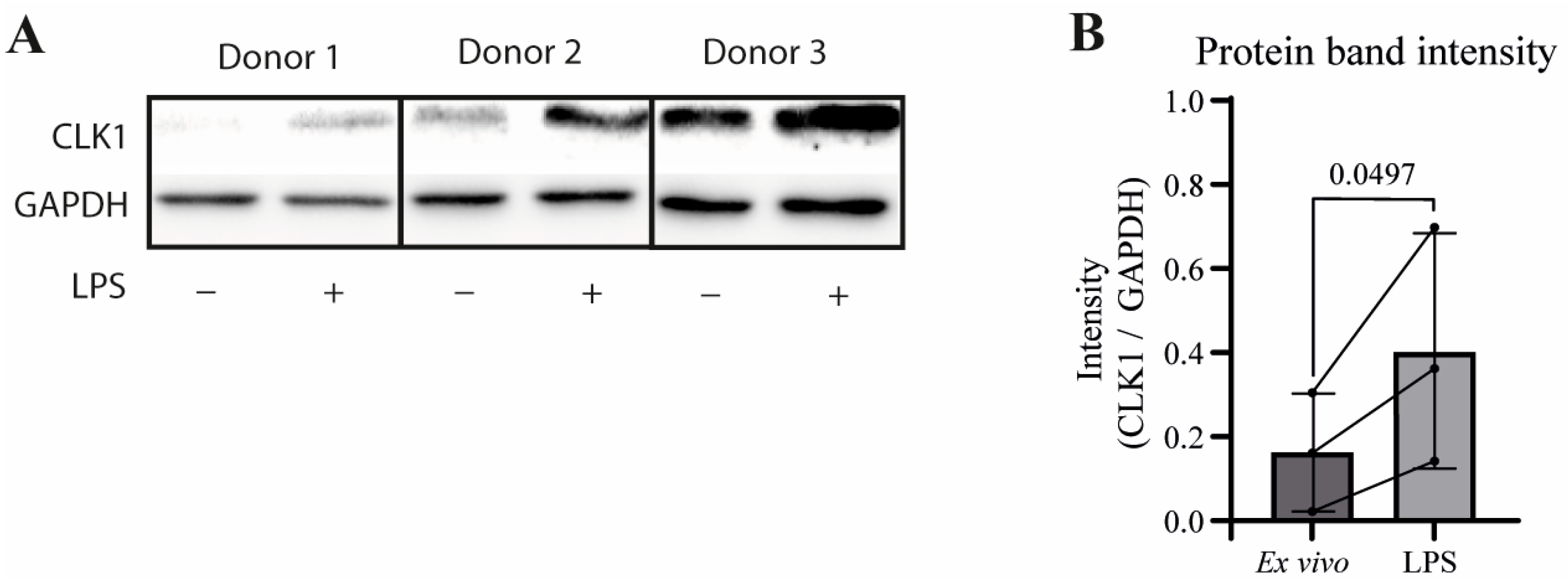

3.2. Validation of CLK1 Isoform Shift at RNA and Protein Levels Reveals Alternative Splicing as a Regulator of CLK1+4 Protein Expression

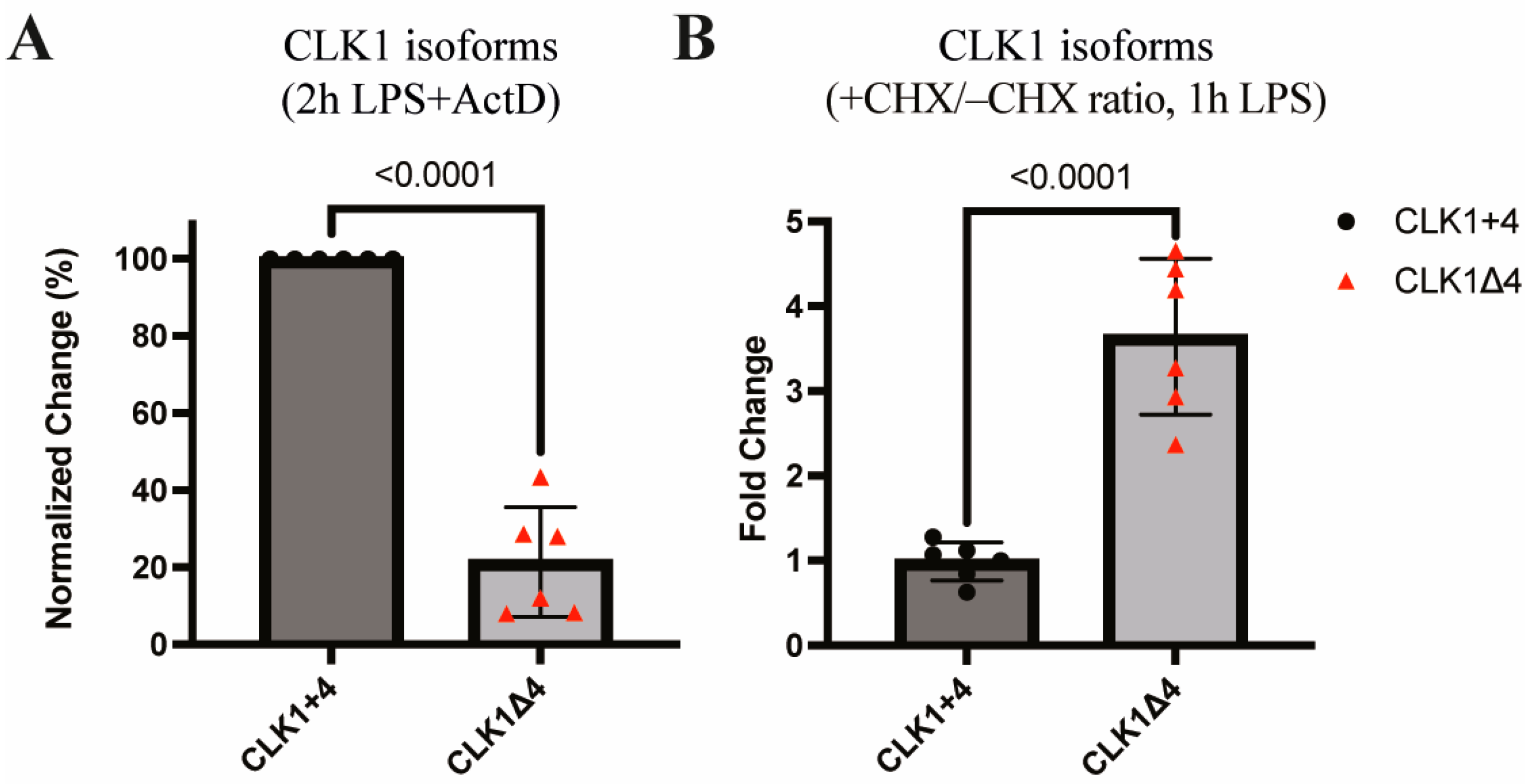

3.3. CLK1 Isoforms Exhibit Differential Stability and Nonsense-Mediated Decay Susceptibility

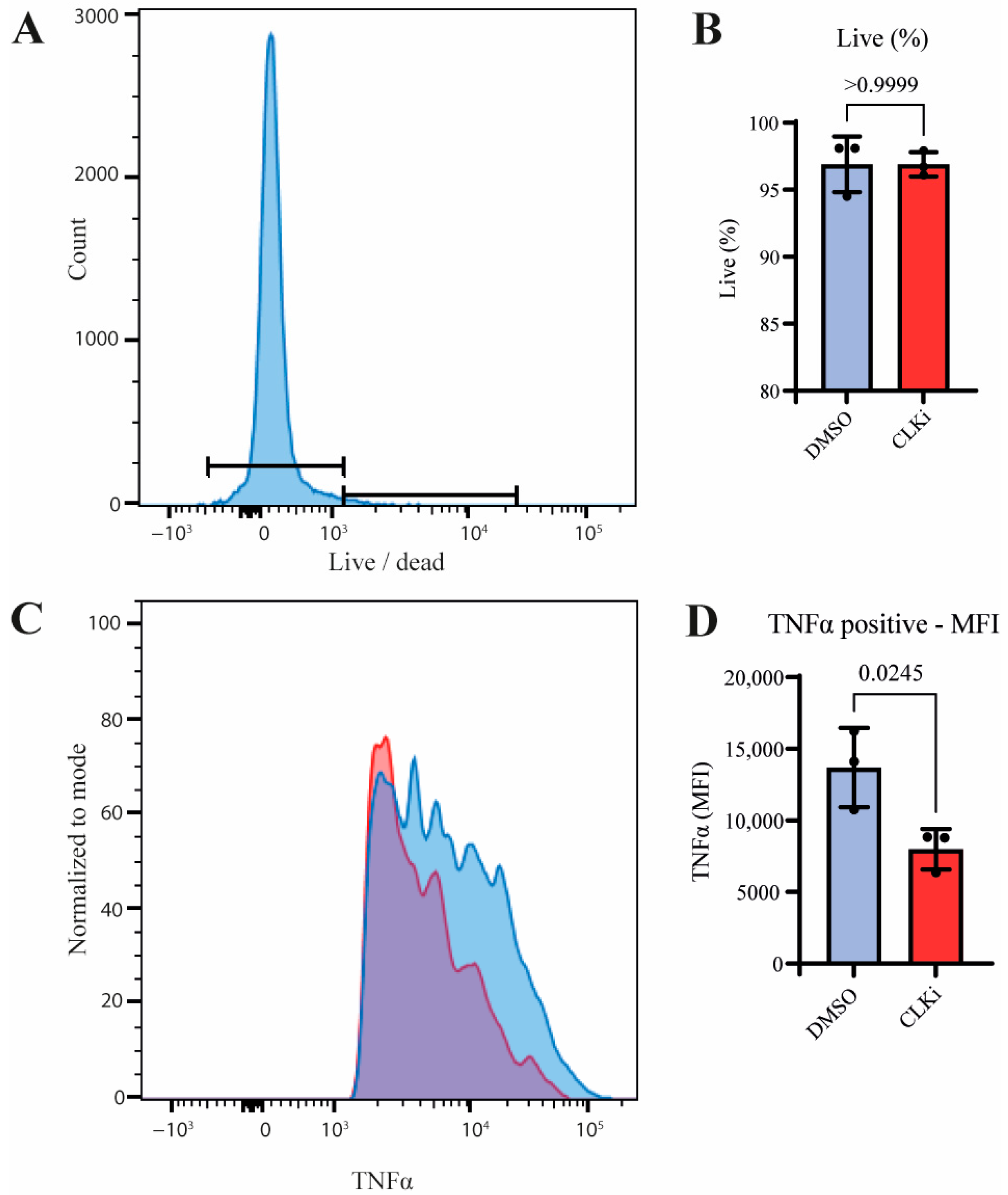

3.4. CLK1 Activity Promotes TNF Production in Stimulated Monocytes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLK1 | Cdc2-like kinase 1 |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| WB | Western Blot |

| RT-QPCR | Reverse transcriptase Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| FACS | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

References

- Schaub, A.; Glasmacher, E. Splicing in immune cells-mechanistic insights and emerging topics. Int. Immunol. 2017, 29, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.W. Consequences of regulated pre-mRNA splicing in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelon, A.v.H.M.; Sijbers, L.J.P.M.; Scholman, R.C.; Picavet, L.W.; de Ligt, A.; van Ginneken, D.; Erkens, R.G.A.; Calis, J.J.A.; Vastert, S.J.; van Loosdregt, J. Native long-read RNA sequencing of human monocytes reveals activation-induced alternative splicing toward functional isoforms. Nat. Commun. 2025. under revision. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, N.M.; Lynch, K.W. Control of alternative splicing in immune responses: Many regulators, many predictions, much still to learn. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 253, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Shai, O.; Lee, L.J.; Frey, B.J.; Blencowe, B.J. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1413–1415, Erratum in Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.T.; Sandberg, R.; Luo, S.; Khrebtukova, I.; Zhang, L.; Mayr, C.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Schroth, G.P.; Burge, C.B. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Lu, L.; Cai, S.; Chen, J.; Lin, W.; Han, F. Alternative Splicing: A New Cause and Potential Therapeutic Target in Autoimmune Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 713540, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1513491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haaren, M.J.H.; Steller, L.B.; Vastert, S.J.; Calis, J.J.A.; van Loosdregt, J. Get Spliced: Uniting Alternative Splicing and Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, S.; Clayton, K.; Been, T.; Fernet-Brochu, R.; Ocando, A.V.; Balachandran, A.; Poirier, M.; Maldonado, R.K.; Shkreta, L.; Boligan, K.F.; et al. Opposing roles of CLK SR kinases in controlling HIV-1 gene expression and latency. Retrovirology 2022, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertznig, H.; Hillebrand, F.; Erkelenz, S.; Schaal, H.; Widera, M. Behind the scenes of HIV-1 replication: Alternative splicing as the dependency factor on the quiet. Virology 2018, 516, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegay, H.J.; Myers, M.P.; Moeslein, F.M.; Landreth, G.E. Biochemical characterization and localization of the dual specificity kinase CLK1. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113 Pt 18, 3241–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Song, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, S.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, P.; Chen, S.; Du, J.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y.; et al. Targeting SRSF10 might inhibit M2 macrophage polarization and potentiate anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Commun. 2024, 44, 1231–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.W.; Hu, J.F.; Pan, J.J.; Liao, C.Y.; Zhang, J.Q.; Chen, J.Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; et al. CLK1/SRSF5 pathway induces aberrant exon skipping of METTL14 and Cyclin L2 and promotes growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertznig, H.; Roesmann, F.; Wilhelm, A.; Heininger, D.; Bleekmann, B.; Elsner, C.; Santiago, M.; Schuhenn, J.; Karakoese, Z.; Benatzy, Y.; et al. SRSF1 acts as an IFN-I-regulated cellular dependency factor decisively affecting HIV-1 post-integration steps. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 935800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.R.; Weindel, C.G.; West, K.O.; Scott, H.M.; Watson, R.O.; Patrick, K.L. SRSF6 balances mitochondrial-driven innate immune outcomes through alternative splicing of BAX. Elife 2022, 11, e82244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, G.H.; Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Pimanda, J.E.; Zanini, F. Analysing high-throughput sequencing data in Python with HTSeq 2.0. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 2943–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.D.; Soulette, C.M.; van Baren, M.J.; Hart, K.; Hrabeta-Robinson, E.; Wu, C.J.; Brooks, A.N. Full-length transcript characterization of SF3B1 mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals downregulation of retained introns. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abugessaisa, I.; Noguchi, S.; Hasegawa, A.; Kondo, A.; Kawaji, H.; Carninci, P.; Kasukawa, T. refTSS: A Reference Data Set for Human and Mouse Transcription Start Sites. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2407–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The FANTOM Consortium and the RIKEN PMI and CLST (DGT). A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature 2014, 507, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo-Palacios, F.J.; Arzalluz-Luque, A.; Kondratova, L.; Salguero, P.; Mestre-Tomas, J.; Amorin, R.; Estevan-Morio, E.; Liu, T.; Nanni, A.; McIntyre, L.; et al. SQANTI3: Curation of long-read transcriptomes for accurate identification of known and novel isoforms. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trincado, J.L.; Entizne, J.C.; Hysenaj, G.; Singh, B.; Skalic, M.; Elliott, D.J.; Eyras, E. SUPPA2: Fast, accurate, and uncertainty-aware differential splicing analysis across multiple conditions. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitting-Seerup, K.; Sandelin, A. IsoformSwitchAnalyzeR: Analysis of changes in genome-wide patterns of alternative splicing and its functional consequences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4469–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Andreeva, A.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Llinares-Lopez, F.; Meng-Papaxanthos, L.; et al. The Pfam protein families database: Embracing AI/ML. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D523–D534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vroonhoven, E.C.N.; Picavet, L.W.; Scholman, R.C.; van den Dungen, N.A.M.; Mokry, M.; Evers, A.; Lebbink, R.J.; Calis, J.J.A.; Vastert, S.J.; van Loosdregt, J. N(6)-Methyladenosine Directly Regulates CD40L Expression in CD4(+) T Lymphocytes. Biology 2023, 12, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkreta, L.; Delannoy, A.; Toutant, J.; Chabot, B. Regulatory interplay between SR proteins governs CLK1 kinase splice variants production. RNA 2024, 30, 1596–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzor, S.; Zorzou, P.; Bowler, E.; Porazinski, S.; Wilson, I.; Ladomery, M. Autoregulation of the human splice factor kinase CLK1 through exon skipping and intron retention. Gene 2018, 670, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarco, J.A.; Xing, Y.; Caceres, M.; Calarco, J.P.; Xiao, X.; Pan, Q.; Lee, C.; Preuss, T.M.; Blencowe, B.J. Global analysis of alternative splicing differences between humans and chimpanzees. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2963–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mossawi, H.; Yager, N.; Taylor, C.A.; Lau, E.; Danielli, S.; de Wit, J.; Gilchrist, J.; Nassiri, I.; Mahe, E.A.; Lee, W.; et al. Context-specific regulation of surface and soluble IL7R expression by an autoimmune risk allele. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbertson, M.R. RNA surveillance. Unforeseen consequences for gene expression, inherited genetic disorders and cancer. Trends Genet. 1999, 15, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y. Expansion of Splice-Switching Therapy with Antisense Oligonucleotides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, G.J. The immunobiology and clinical potential of immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2000, 68, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermiston, M.L.; Xu, Z.; Weiss, A. CD45: A critical regulator of signaling thresholds in immune cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Saleh, Q.W.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Tepel, M. Metabolic regulation of forkhead box P3 alternative splicing isoforms and their impact on health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1278560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Hoyos, L.; Knorr, K.; Abdel-Wahab, O. Aberrant RNA Splicing in Cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2019, 3, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez-Costa, A.; Perez-Sanchez, C.; Patino-Trives, A.M.; Luque-Tevar, M.; Font, P.; Arias de la Rosa, I.; Roman-Rodriguez, C.; Abalos-Aguilera, M.C.; Conde, C.; Gonzalez, A.; et al. Splicing machinery is impaired in rheumatoid arthritis, associated with disease activity and modulated by anti-TNF therapy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitamura, K.; Nimura, K. Regulation of RNA Splicing: Aberrant Splicing Regulation and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, H.; Nishimura, K.; Yoshimi, A. Aberrant RNA splicing and therapeutic opportunities in cancers. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.K.; Byun, H.S.; Lee, H.; Jeon, J.; Lee, Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, E.H.; Kim, J.; Hong, J.H.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Intron-derived aberrant splicing of A20 transcript in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2013, 52, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fu, X.D.; Ares, M., Jr. Context-dependent control of alternative splicing by RNA-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irimia, M.; Blencowe, B.J. Alternative splicing: Decoding an expansive regulatory layer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2012, 24, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Haaren, M.J.H.; Bodelón, A.; Sijbers, L.J.P.M.; Scholman, R.; Picavet, L.W.; Calis, J.J.A.; Vastert, S.J.; van Loosdregt, J. Regulation of CLK1 Isoform Expression by Alternative Splicing in Activated Human Monocytes Contributes to Activation-Associated TNF Production. Cells 2025, 14, 1925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231925

van Haaren MJH, Bodelón A, Sijbers LJPM, Scholman R, Picavet LW, Calis JJA, Vastert SJ, van Loosdregt J. Regulation of CLK1 Isoform Expression by Alternative Splicing in Activated Human Monocytes Contributes to Activation-Associated TNF Production. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231925

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Haaren, Maurice J. H., Alejandra Bodelón, Lyanne J. P. M. Sijbers, Rianne Scholman, Lucas W. Picavet, Jorg J. A. Calis, Sebastiaan J. Vastert, and Jorg van Loosdregt. 2025. "Regulation of CLK1 Isoform Expression by Alternative Splicing in Activated Human Monocytes Contributes to Activation-Associated TNF Production" Cells 14, no. 23: 1925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231925

APA Stylevan Haaren, M. J. H., Bodelón, A., Sijbers, L. J. P. M., Scholman, R., Picavet, L. W., Calis, J. J. A., Vastert, S. J., & van Loosdregt, J. (2025). Regulation of CLK1 Isoform Expression by Alternative Splicing in Activated Human Monocytes Contributes to Activation-Associated TNF Production. Cells, 14(23), 1925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231925