Advanced Glycation End Products Promote PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells via RAGE/TLR4-Mediated PKC–NF-κB Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Preparation of AGEs

2.3. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (Real-Time PCR)

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immune-Sorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.6. Immunofluorescence: The Nuclear Accumulation of NF-κB

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

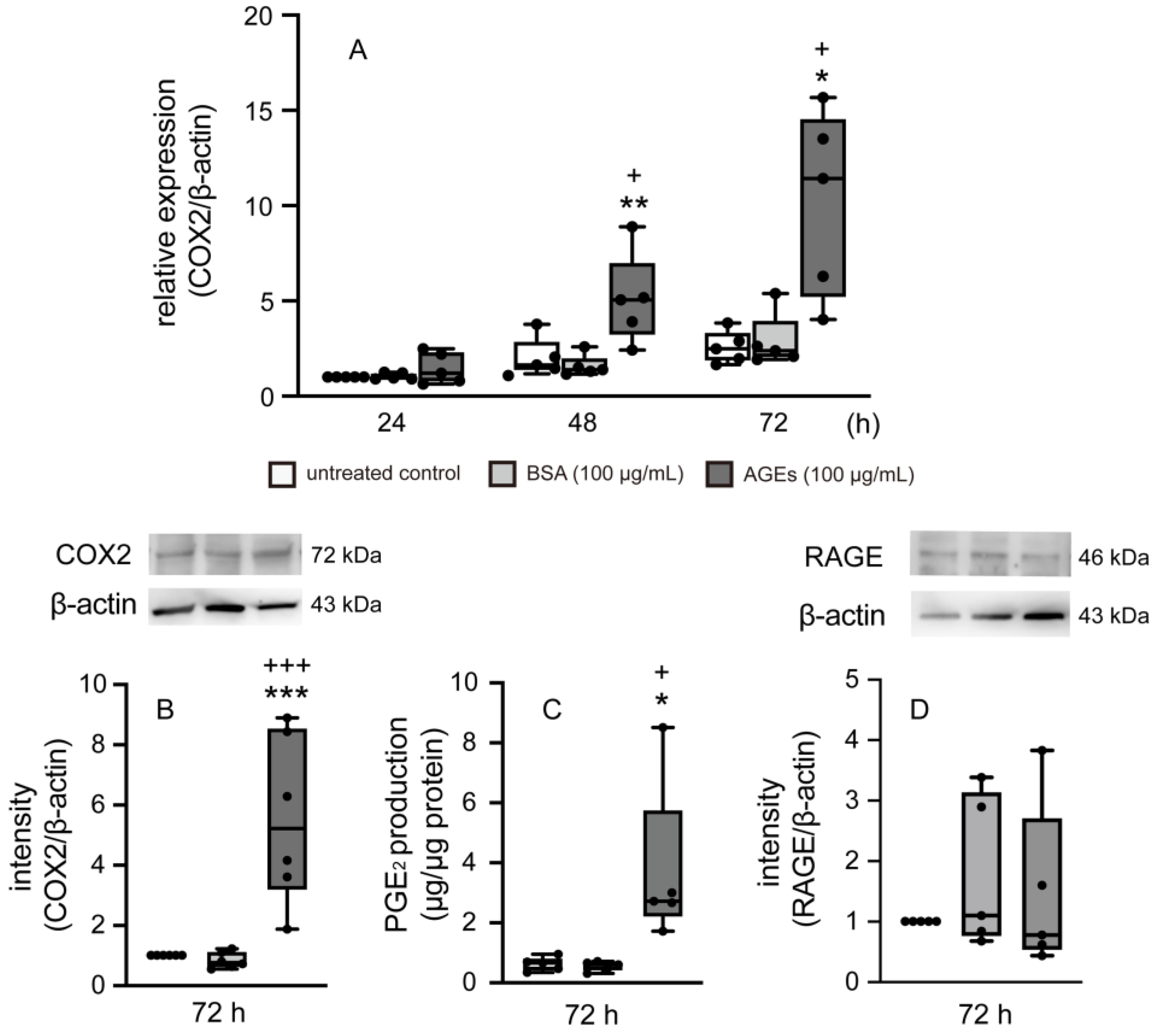

3.1. AGEs Increased COX2 and PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells

3.2. RAGE Regulated the Expression of COX2, TLR4, and PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells

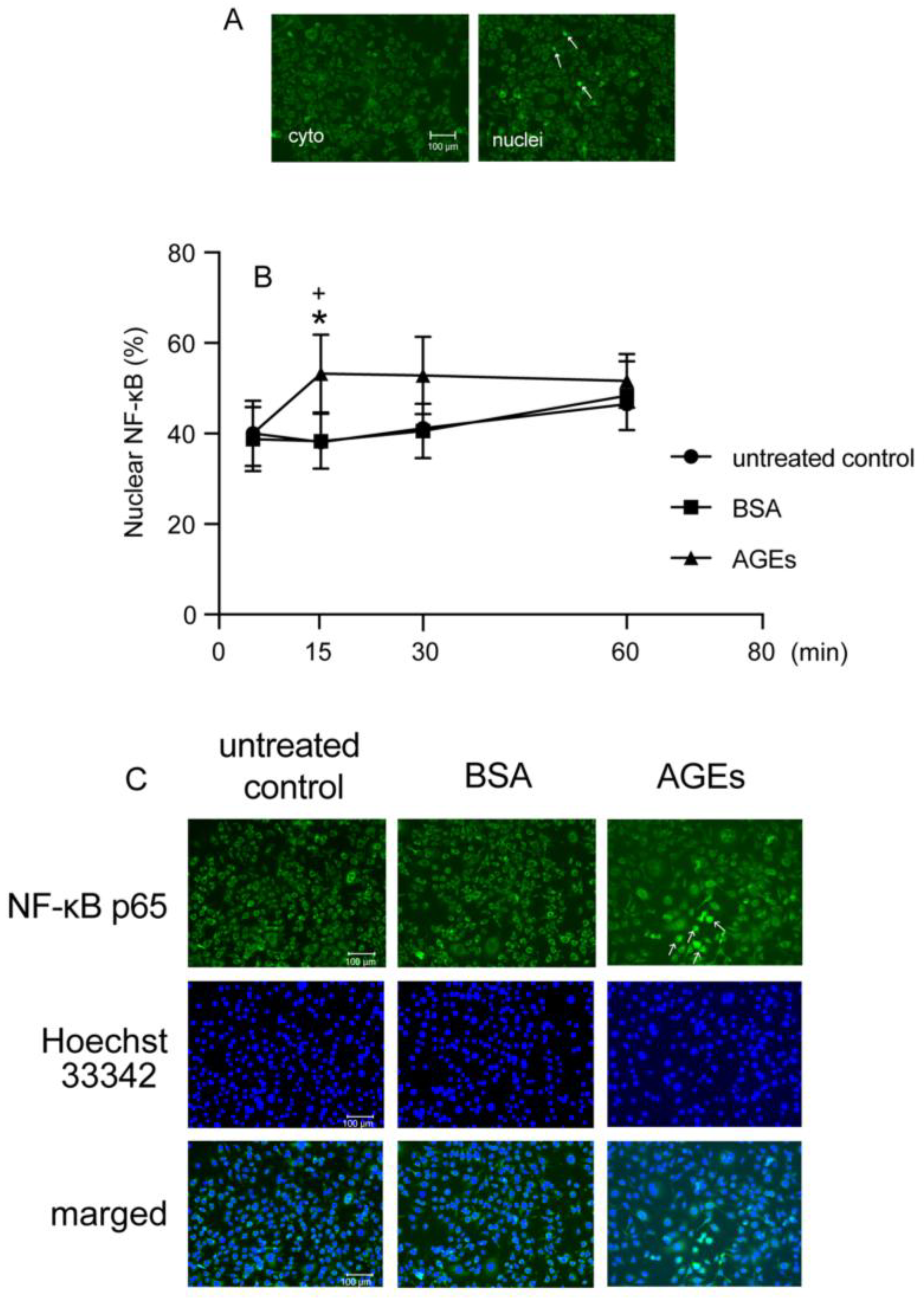

3.3. AGEs Increased NF-κB Nuclear Accumulation in Ca9-22 Cells

3.4. AGEs Increased p-PKC via TLR4 in Ca9-22 Cells

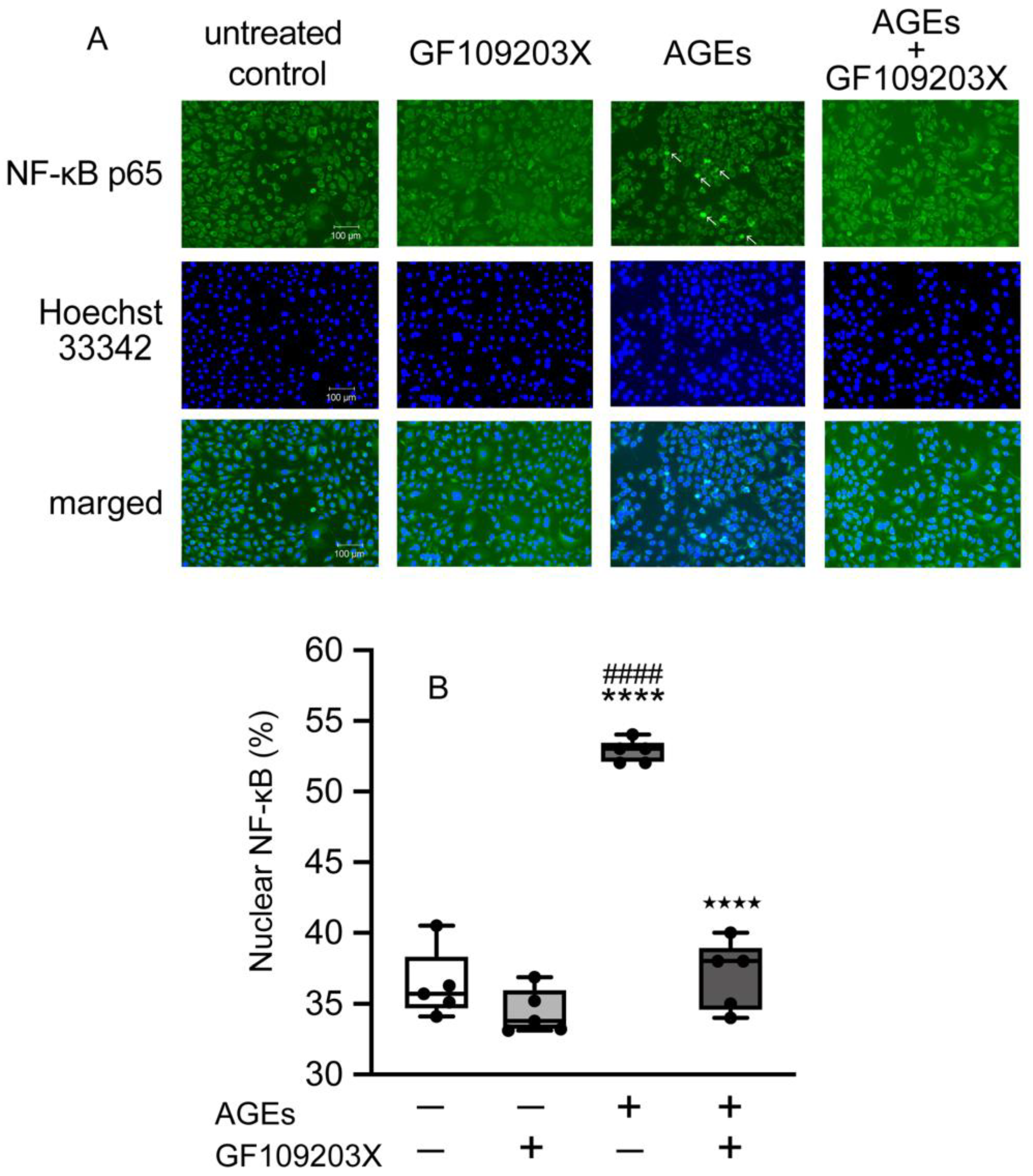

3.5. PKC-Mediated NF-κB Nuclear Accumulation in Ca9-22 Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGEs | advanced glycation end-products |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes |

| RAGE | receptor for advanced glycation end-products |

| IL-1 | interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | interleukin-8 |

| IL-17 | interleukin-17 |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| RANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| COX1 | cyclooxygenase 1 |

| COX2 | cyclooxygenase 2 |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| p-PKC | phosphorylated protein kinase C |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kappa B |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

References

- Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Ye, C.; Wu, W.; Liao, G.; Lu, Y.; Huang, P. Changes in Advanced Glycation End Products, Beta-Defensin-3, and interleukin-17 during Diabetic Periodontitis Development in Rhesus. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 243, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.; Petroianu, G.; Adem, A. Advanced Glycation End Products and Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanko, P.; Holla, L.I. Bidirectional Association between Diabetes Mellitus and Inflammatory Periodontal Disease. A Review. Biomed. Pap. 2014, 158, 035–038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopino, A.M. Periodontitis and Diabetes Interrelationships: Role of Inflammation. Ann. Periodontol. Am. Acad. Periodontol. 2001, 6, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, B.; Park, B.; Bartold, P.M. Periodontitis and Type II Diabetes: A Two-Way Relationship. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2013, 11, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeting, P.E.; Rifas, L.; Harris, S.A.; Colvard, D.S.; Spelsberg, T.C.; Peck, W.A.; Riggs, L.B. Evidence for Interleukin-1β Production by Cultured Normal Human Osteoblast-like Cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2009, 6, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M.; Tanabe, N.; Mitsui, N.; Tanaka, H.; Suzuki, N.; Takeichi, O.; Sugaya, A.; Maeno, M. Lipopolysaccharide Stimulates the Production of Prostaglandin E2 and the Receptor Ep4 in Osteoblasts. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, R.C. The Role of Inflammatory Mediators in the Pathogenesis of Periodontal Disease. J. Periodontal Res. 1991, 26, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Tanabe, N.; Manaka, S.; Naito, M.; Sekino, J.; Takayama, T.; Kawato, T.; Torigoe, G.; Kato, S.; Tsukune, N.; et al. LIPUS Suppressed LPS-Induced IL-1α through the Inhibition of NF-ΚB Nuclear Translocation via AT1-PLCβ Pathway in MC3T3-E1 Cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2017, 232, 3337–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, C.D. Prostaglandins and Leukotrienes: Advances in Eicosanoid Biology. Science 2001, 294, 1871–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenbaum, F. Proinflammatory Cytokines, Prostaglandins, and the Chondrocyte: Mechanisms of Intracellular Activation. Jt. Bone Spine 2000, 67, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhouayek, M.; Muccioli, G.G. COX-2-Derived Endocannabinoid Metabolites as Novel Inflammatory Mediators. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, N.; Tomita, K.; Manaka, S.; Ichikawa, R.; Takayama, T.; Kawato, T.; Ono, M.; Masai, Y.; Utsu, A.; Suzuki, N.; et al. Co-Stimulation of AGEs and LPS Induces Inflammatory Mediators through PLCγ1/JNK/NF-ΚB Pathway in MC3T3-E1 Cells. Cells 2023, 12, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, T.; Sharma, E.; Sehgal, A.; Kaur, I.; Kumar, A.; Arora, R.; Pal, G.; Kakkar, M.; Kumar, R.; Bungau, S. Expatiating the Molecular Approaches of HMGB1 in Diabetes Mellitus: Highlighting Signalling Pathways via RAGE and TLRs. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 1869–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J. Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)/Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) Regulates Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion by NF-ΚB Activation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 5588–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Cui, Q.; Xu, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Wang, X. Toll-like Receptor 4 Plays a Key Role in Advanced Glycation End Products-Induced M1 Macrophage Polarization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 531, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, R.; Coral, K.; Bharathidevi, S.R. RAGE Silencing Deters CML-AGE Induced Inflammation and TLR4 Expression in Endothelial Cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 206, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscat, J.; Diaz-Meco, M.T.; Rennert, P. NF-ΚB Activation by Protein Kinase C Isoforms and B-Cell Function. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, K.; Mecklenbräuker, I.; Schmedt, C.; Tarakhovsky, A. B Cell Immunity Regulated by the Protein Kinase C Family. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 987, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancurova, I.; Miskolci, V.; Davidson, D. NF-ΚB Activation in Tumor Necrosis Factor α-Stimulated Neutrophils Is Mediated by Protein Kinase Cδ: CORRELATION TO NUCLEAR IκBα. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19746–19752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asehnoune, K.; Strassheim, D.; Mitra, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Abraham, E. Involvement of PKCα/β in TLR4 and TLR2 Dependent Activation of NF-ΚB. Cell Signal. 2005, 17, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yano, S.; Yamauchi, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Sugimoto, T. The Combination of High Glucose and Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs) Inhibits the Mineralization of Osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 Cells through Glucose-Induced Increase in the Receptor for AGEs. Horm. Metab. Res. 2007, 39, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tanaka, K.I.; Notsu, M.; Ogawa, N.; Yano, S.; Sugimoto, T. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs), but Not High Glucose, Inhibit the Osteoblastic Differentiation of Mouse Stromal ST2 Cells Through the Suppression of Osterix Expression, and Inhibit Cell Growth and Increasing Cell Apoptosis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2012, 91, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.-I.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kaji, H.; Kanazawa, I.; Sugimoto, T. Advanced glycation end products suppress osteoblastic differentiation of stromal cells by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 438, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.-I.; Kanazawa, I.; Yamaguchi, T.; Yano, S.; Kaji, H.; Sugimoto, T. Active vitamin D possesses beneficial effects on the interaction between muscle and bone. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlstrom, B.L.; Michalowicz, B.S.; Johnson, N.W. Periodontal Diseases. Lancet 2005, 366, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plemmenos, G.; Piperi, C. Pathogenic Molecular Mechanisms in Periodontitis and Peri-Implantitis: Role of Advanced Glycation End Products. Life 2022, 12, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, J.; Waite, M.; Tobler, J.; Catalfamo, D.L.; Koutouzis, T.; Katz, J.; Wallet, S.M. The Role of Hyperglycemia in Mechanisms of Exacerbated Inflammatory Responses within the Oral Cavity. Cell Immunol. 2011, 272, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Graves, D.T.; Ding, Z.; Yang, Y. The Impact of Diabetes on Periodontal Diseases. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 82, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.T.; Joseph, B.; Sorsa, T.; Mauramo, M.; Anil, S.; Waltimo, T. Expression of Advanced Glycation End Products and Their Receptors in Diabetic Periodontitis Patients. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 2784–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiden, M.F.J.; Pham, C.; Kashket, S. Glucose Toxicity Effect and Accumulation of Methylglyoxal by the Periodontal Anaerobe Bacteroides Forsythus. Anaerobe 2004, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashket, S.; Maiden, M.F.J.; Haffajee, A.D.; Kashket, E.R. Accumulation of Methylglyoxal in the Gingival Crevicular Fluid of Chronic Periodontitis Patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.; Jayasinghe, T.N.; Eberhard, J. Are Inflamed Periodontal Tissues Endogenous Source of Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs) in Individuals with and without Diabetes Mellitus? A Systematic Review. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kido, R.; Hiroshima, Y.; Kido, J.I.; Ikuta, T.; Sakamoto, E.; Inagaki, Y.; Naruishi, K.; Yumoto, H. Advanced Glycation End-Products Increase Lipocalin 2 Expression in Human Oral Epithelial Cells. J. Periodontal Res. 2020, 55, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Tan, R.-Z.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Yu, Y.; Yu, C. Calycosin Ameliorates Diabetes-Induced Renal Inflammation via the NF-κB Pathway In Vitro and In Vivo. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 1671–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, F.A. Cyclooxygenase Enzymes: Regulation and Function. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agúndez, J.A.; Blanca, M.; Cornejo-García, J.A.; García-Martín, E. Pharmacogenomics of Cyclooxygenases. Pharmacogenomics 2015, 16, 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Qu, Z.; Gong, Z.; Li, J.; Xiao, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; et al. The Role of TLR4 on PGC-1α-Mediated Oxidative Stress in Tubular Cell in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 6296802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendra, E.; Riabov, V.; Mossel, D.M.; Sevastyanova, T.; Harmsen, M.C.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Macrophage Activation and Function in Diabetes. Immunobiology 2019, 224, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Pan, S.; Zhu, L.; Cui, Q.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Advanced Glycation End Products Induce Atherosclerosis via RAGE/TLR4 Signaling Mediated-M1 Macrophage Polarization-Dependent Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Conversion. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9763377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, Y.; Hou, F.F.; Nie, J. AGE-LDL Activates Toll Like Receptor 4 Pathway and Promotes Inflammatory Cytokines Production in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E. Nuclear Factor-KappaB and Its Role in Sepsis-Associated Organ Failure. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 187, S364–S369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, I.M.; Stevenson, J.K.; Schwarz, E.M.; Van Antwerp, D.; Miyamoto, S. Rel/NF-ΚB/IκB Family: Intimate Tales of Association and Dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2723–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Karin, M. Missing Pieces in the NF-ΚB Puzzle. Cell 2002, 109, S81–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saijo, K.; Mecklenbräuker, I.; Santana, A.; Leitger, M.; Schmedt, C.; Tarakhovsky, A. Protein Kinase C β Controls Nuclear Factor ΚB Activation in B Cells Through Selective Regulation of the IκB Kinase α. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 195, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.T.; Guo, B.; Kawakami, Y.; Sommer, K.; Chae, K.; Humphries, L.A.; Kato, R.M.; Kang, S.; Patrone, L.; Wall, R.; et al. PKC-β Controls IκB Kinase Lipid Raft Recruitment and Activation in Response to BCR Signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Guan, Y.; Ma, Y.; Cui, Q.; Tang, Z.; Li, J.; Zu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, J.; et al. Advanced Glycation End Products Correlate with Breast Cancer Metastasis by Activating RAGE/TLR4 Signaling. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamputu, J.C.; Renier, G. Signalling Pathways Involved in Retinal Endothelial Cell Proliferation Induced by Advanced Glycation End Products: Inhibitory Effect of Gliclazide. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2004, 6, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Yang, T.; Xie, X.; Chen, M. The Role of Profilin-1 in Endothelial Cell Injury Induced by Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2013, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Tao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, M. 4’-Methoxyresveratrol Alleviated AGE-Induced Inflammation via RAGE-Mediated NF-ΚB and NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Molecules 2018, 23, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Niu, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Xie, A. RAGE Silencing Ameliorates Neuroinflammation by Inhibition of P38-NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway in Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Lv, Q.; Bi, X.; Liu, X.; Fu, G.; Zou, Y.; Ge, J.; Chen, Z.; et al. Dendritic Cell-Mediated Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation Is Regulated by the RAGE-TLR4-PKCβ1 Signaling Pathway in Diabetic Atherosclerosis. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ono, M.; Tanabe, N.; Ichikawa, R.; Tomita, K.; Manaka, S.; Seki, H.; Imai, Y.; Aoki, M.; Masai, Y.; Takayama, T.; et al. Advanced Glycation End Products Promote PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells via RAGE/TLR4-Mediated PKC–NF-κB Pathway. Cells 2025, 14, 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231911

Ono M, Tanabe N, Ichikawa R, Tomita K, Manaka S, Seki H, Imai Y, Aoki M, Masai Y, Takayama T, et al. Advanced Glycation End Products Promote PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells via RAGE/TLR4-Mediated PKC–NF-κB Pathway. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231911

Chicago/Turabian StyleOno, Misae, Natsuko Tanabe, Risa Ichikawa, Keiko Tomita, Soichiro Manaka, Hideaki Seki, Yuri Imai, Mayu Aoki, Yuma Masai, Tadahiro Takayama, and et al. 2025. "Advanced Glycation End Products Promote PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells via RAGE/TLR4-Mediated PKC–NF-κB Pathway" Cells 14, no. 23: 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231911

APA StyleOno, M., Tanabe, N., Ichikawa, R., Tomita, K., Manaka, S., Seki, H., Imai, Y., Aoki, M., Masai, Y., Takayama, T., Suzuki, N., & Sato, S. (2025). Advanced Glycation End Products Promote PGE2 Production in Ca9-22 Cells via RAGE/TLR4-Mediated PKC–NF-κB Pathway. Cells, 14(23), 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231911