Bridging the Translational Gap: Rethinking Smooth Muscle Cell Plasticity in Atherosclerosis Through Human-Relevant In Vitro Models

Highlights

- Human arterial smooth muscle cells exhibit extensive phenotypic plasticity, and current in vitro systems capture different aspects of this spectrum to varying degrees.

- A systematic comparison of in vitro models highlights the context-dependent utility and the specific conditions under which each model is most informative.

- Careful model selection and benchmarking against human multi-omic datasets are essential to ensure biological and translational relevance.

- All models are useful when appropriately aligned with the hypothesis and interpreted within their biological limitations, with complexity incorporated only when mechanistically justified.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. SMC Plasticity in Vascular Biology

1.2. SMC Plasticity in Disease

1.3. The Translational Gap from Mice to Humans

1.4. Aims and Scope of This Review

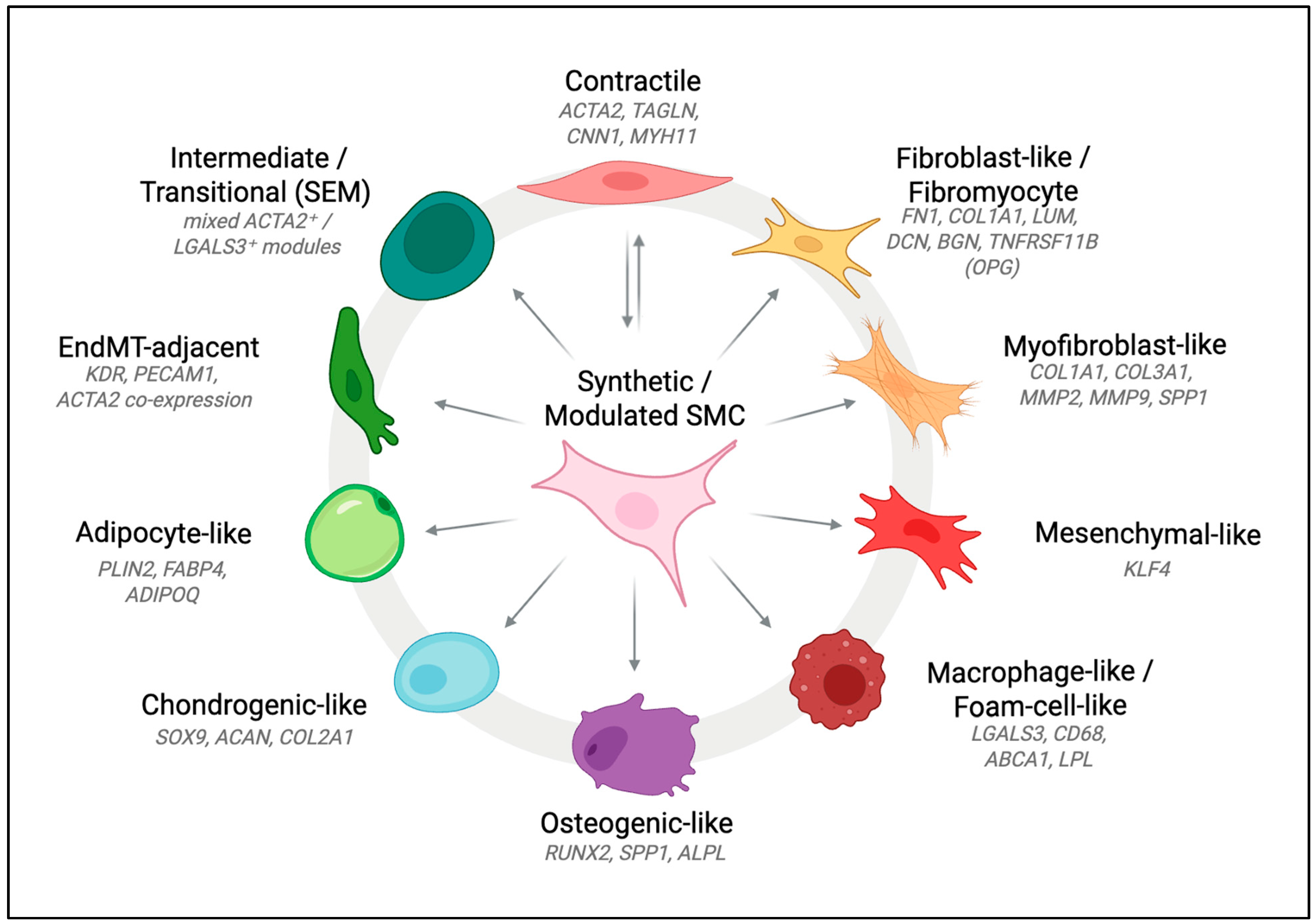

2. SMC Phenotypic Diversity in Atherosclerosis

2.1. From a Binary View to a Spectrum of States

2.2. Expanding the Spectrum: Emerging SMC Phenotypes

2.2.1. Insights from Murine Lineage Tracing

2.2.2. Transcriptomic Insights into Human Atherosclerotic Lesions

2.3. The Translational Divide: Comparing Murine and Human Phenotypes

| Phenotype/State | Key Markers/Signatures | Evidence in Animal Models | Evidence in Humans | Representative Studies | Notes/Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractile (baseline) | ACTA2, MYH11, TAGLN, CNN1 | Robustly detected in healthy vessels and lineage-traced SMCs in ApoE−/− mice; downregulated under atherogenic conditions. | Rarely preserved in advanced plaques; contractile gene expression reduced in human lesions. | Skalli et al., J Cell Biol 1986 [24] Aikawa et al., Circ Res 1993 [27] Wirka et al., Nat Med 2019 [18] | Canonical markers often decline in late-stage disease, making lineage assignment difficult. |

| Fibroblast-like/Fibromyocyte | FN1, COL1A1, LUM, DCN, BGN, OPG (TNFRSF11B) | Robustly detected in murine lineage tracing; proliferative ECM-producing cells forming the fibrous cap. | Detected in human scRNA-seq datasets and spatial transcriptomics; linked to cap stability. | Wirka et al., Nat Med 2019 [18] Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42] Alencar et al., Circulation 2020 [47] | Highly conserved state across species; dominant in stable lesions. |

| Myofibroblast-like | COL1A1, COL3A1, MMP2, MMP9, OPN (SPP1) | Observed in murine injury and atherosclerosis models; derived from dedifferentiated SMCs. | Confirmed in human coronary plaque datasets; shares ECM-remodelling and proliferative features. | Shankman et al., Nat Med 2015 [10] Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42] | Boundaries between “synthetic” and “fibroblast-like” phenotypes are context-dependent. |

| Mesenchymal-like | KLF4-linked modules; ECM and cytoskeletal genes | Identified in Myh11-CreERT2; ApoE−/− lineage tracing as intermediate transition state. | Confirmed in human coronary scRNA-seq datasets showing partial contractile and mesenchymal programmes. | Wirka et al., Nat Med 2019 [18] Alencar et al., Circulation 2020 [47] | May represent a transient state rather than a stable end-state. |

| Macrophage-like/Foam-cell-like | LGALS3, CD68, ABCA1, LPL | Observed in ApoE−/− mouse lesions derived from SMCs; fate-mapping confirms SMC origin. | Identified in human plaques but rare; some clusters phenotypically resemble macrophages while retaining SMC markers. | Allahverdian et al., Circulation 2014 [54] Wang et al., Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019 [43] Li et al., Cell Discovery 2021 [53] | Frequency in humans remains debated due to lineage ambiguity and marker overlap with myeloid cells. |

| Osteogenic-like | RUNX2, OPN (SPP1), BGLAP, ALPL | Strong evidence from murine lineage tracing; enriched in advanced calcified lesions. | Detected in human coronary arteries and calcified plaques; associated with plaque instability. | Speer et al., Circ Res 2009 [56] Sun et al., Circ Res 2012 [57] Alsaigh et al., Comm Bio 2022 [55] | Indicates shared mechanism of SMC-driven calcification across species. |

| Chondrogenic-like | SOX9, ACAN, COL2A1 | Reported in murine lineage tracing during atherosclerosis progression. | Present in human single-cell datasets; contributes to proteoglycan-rich ECM and plaque stiffness. | Speer et al., Circ Res 2009 [56] Xu et al., Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012 [58] Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42] | Overlaps transcriptionally with osteogenic programmes; context-dependent activation. |

| Adipocyte-like | PLIN2, FABP4, ADIPOQ (low) | Detected in mice (Sca1+ SMCs, though lineage origin debated). | No clear human homolog (Sca1 is murine-specific); relevance uncertain. | Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42] Mosquera et al., Cell Reports 2023 [50] | May represent metabolic reprogramming rather than true adipogenic differentiation. |

| Intermediate/Transitional (SEM) | Mixed ACTA2+/LGALS3+ modules | Observed in high-resolution murine lineage tracing between contractile and fibroblast-like states. | Human scRNA-seq datasets suggest similar intermediate phenotypes, though less clearly resolved. | Wirka et al., Nat Med 2019 [18] Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42] | Likely under-detected in human studies due to cross-sectional sampling. |

| EndMT-adjacent/Hybrid EC–SMC | KDR, PECAM1, ACTA2 (co-expression) | Occasionally noted in murine atherosclerosis at lesion borders. | Human carotid single-cell atlases reveal EC clusters co-expressing SMC markers. | Depuydt et al., Circ Res 2020 [48] Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42] | Represents a boundary phenotype rather than a canonical SMC fate. |

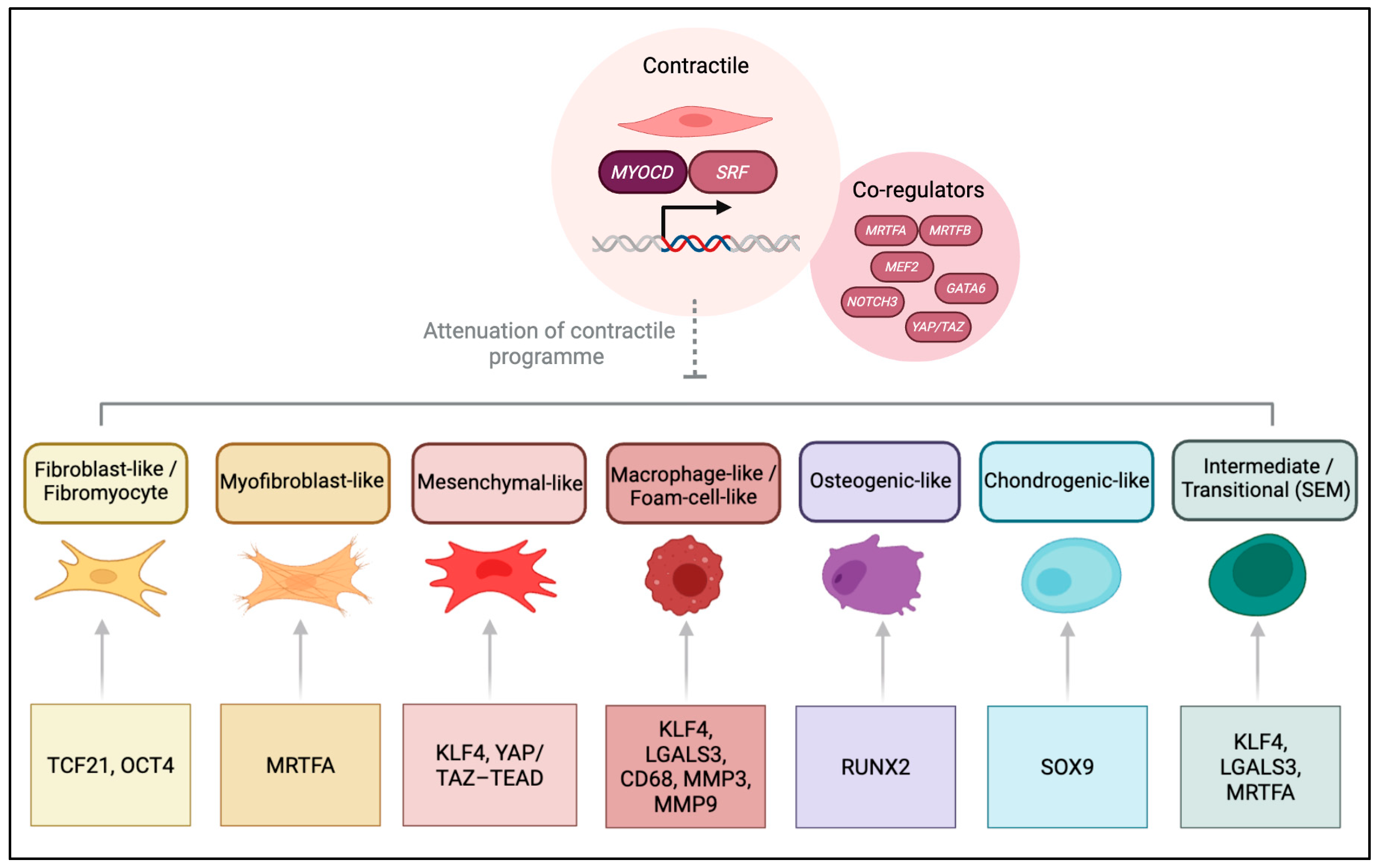

3. Regulatory Mechanisms and Paradigm Shift in SMC Plasticity

3.1. Transcriptional Control of SMC Identity

3.1.1. Maintenance of the Contractile State

3.1.2. Transcriptional Regulation Driving Phenotypic Plasticity

3.2. Extracellular Cues and Disease-Relevant Stimuli

3.2.1. ECM Composition

3.2.2. Soluble Factors

3.2.3. Crosstalk with Neighbouring Cells

3.3. Implications for Modelling

| Regulator/Pathway | Primary Function/Mechanism | Associated SMC Phenotype(s) | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRF–MYOCD –MRTF axis | Core transcriptional module driving contractile gene expression (ACTA2, TAGLN, CNN1, MYH11) via CArG-box regulation. MYOCD confers SMC specificity; MRTFs link actin dynamics to transcription. | Contractile (baseline); loss promotes synthetic transition. | SRF/MYOCD depletion reduces contractile markers and increases ECM genes in vivo and in vitro [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. |

| MEF2 | Co-activator of the SRF–MYOCD module; integrates Ca2+ signalling to sustain the contractile programme. | Contractile maintenance. | Upregulates MYOCD and contractile genes in Ca2+-dependent manner [84,85]. |

| YAP/TAZ (TEAD-dependent) | Mechanosensitive regulators coupling cytoskeletal tension and ECM stiffness to SRF–MYOCD signalling. | Contractile maintenance under mechanical stress. | Activation preserves cytoskeletal integrity; dysregulation favours synthetic transition [86,87]. |

| NOTCH3 (RBPJ/HEY) | Promotes differentiation and maturation of vascular SMCs; supports contractile identity. | Contractile maintenance. | Genetic loss impairs vascular maturation and induces synthetic features in mice [88,89,90]. |

| GATA6 | Transcription factor sustaining differentiated contractile state. | Contractile. | Reduced expression linked to dedifferentiation in vascular disease models [91,92]. |

| KLF4 | Represses SRF–MYOCD axis; induces inflammatory and matrix genes (FN1, COL1A1, MMPs, OPN). Activated by PDGF-BB, oxLDL, TNF-α. | Macrophage-like, osteogenic, mesenchymal-like. | SMC-specific Klf4 deletion reduces lesion size and enhances fibrous-cap stability; human scRNA-seq links to mesenchymal signatures [93,94,95]. |

| TCF21 | Inhibits MYOCD–SRF interaction to suppress the contractile programme; drives fibroblast-like transition. | Fibroblast-like (fibromyocyte). | Lineage tracing and human scRNA-seq show cap-forming fibromyocytes dependent on TCF21 [18,19,96,97]. |

| ELK1 | PDGF-BB-induced ETS factor competing with MYOCD for SRF binding, repressing contractile genes. | Synthetic (proliferative). | Enhanced ELK1 activity drives SMC dedifferentiation and neointimal growth in mice [98,99,100,101,102]. |

| OCT4 (POU5F1) | Reactivated pluripotency factor modulating matrix and fibrosis programmes; isoform-specific actions. | Fibroblast-like/matrix-associated states. | Conditional knockout reduces fibrous cap size; human data show enrichment in matrix-regulating clusters; context-dependent [103,104,105,106]. |

| RUNX2 | Master regulator of osteogenic conversion and calcification; suppresses MYOCD. | Osteogenic-like. | SMC-specific Runx2 deletion reduces vascular calcification; osteogenic clusters in human plaques [56,57]. |

| SOX9 | Promotes chondrogenic transition and ECM stiffening; antagonises MYOCD. | Chondrogenic-like/fibrotic. | Overexpression induces chondrogenic markers and stiff ECM in vivo and human arteries [58,108]. |

| PDGF-BB–PDGFRβ | Canonical inducer of SMC phenotypic switch via ERK/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, JAK/STAT, Notch/MMP, JNK pathways; stimulates migration and proliferation. | Synthetic/fibroblast-like. | In vitro and in vivo evidence for SMC dedifferentiation and clonal expansion in lesions [123,124,125,128,129,130]. |

| TGF-β–SMAD2/3 | Context-dependent: supports contractile programme in homeostasis, drives fibrosis after injury. | Contractile (maintenance) or Fibroblast-like (pro-fibrotic). | Dual role supported by animal and human data linking to fibrous-cap stability [79,126,131]. |

| oxLDL/Cholesterol uptake | Induces oxidative and ER stress; activates inflammatory and matrix genes. | Macrophage-like and osteogenic-like. | Murine lineage tracing shows SMC-derived foam cells; human data support restricted conversion [52,94]. |

| IL-1β/TNF-α | Cytokine signalling that represses contractile markers and activates MMPs and inflammatory genes. | Inflammatory/macrophage-like. | Demonstrated in SMC cultures and atherosclerotic murine models [14,94,95,132]. |

| ECM composition (Fibronectin, Laminin, Collagen, Elastin) | ECM proteins govern adhesion, migration and phenotype; fibronectin and collagen I/III promote synthetic state; laminin and collagen IV preserve contractility. | Contractile or Synthetic (dependent on matrix type). | In vitro matrix-coating and in vivo remodelling studies show context-dependent effects [109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119]. |

| ECM stiffness/mechanotransduction | Increased stiffness drives cytoskeletal reorganisation and synthetic switch. | Synthetic/mesenchymal-like. | Substrate-stiffness models and atherosclerotic tissue data support mechanosensitive regulation [116,122]. |

| Endothelial crosstalk | EC-derived signals maintain SMC quiescence and contractility; dysfunction induces dedifferentiation and migration. | Contractile (homeostasis) or Synthetic (pathology). | Co-culture and injury models demonstrate bidirectional influence on SMC fate [134,135,136,137,138,139]. |

| Immune cell crosstalk | Macrophage and T-cell cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) promote inflammatory and migratory SMC states. | Inflammatory/macrophage-like. | Murine and human plaque data show reciprocal inflammatory amplification [142,143]. |

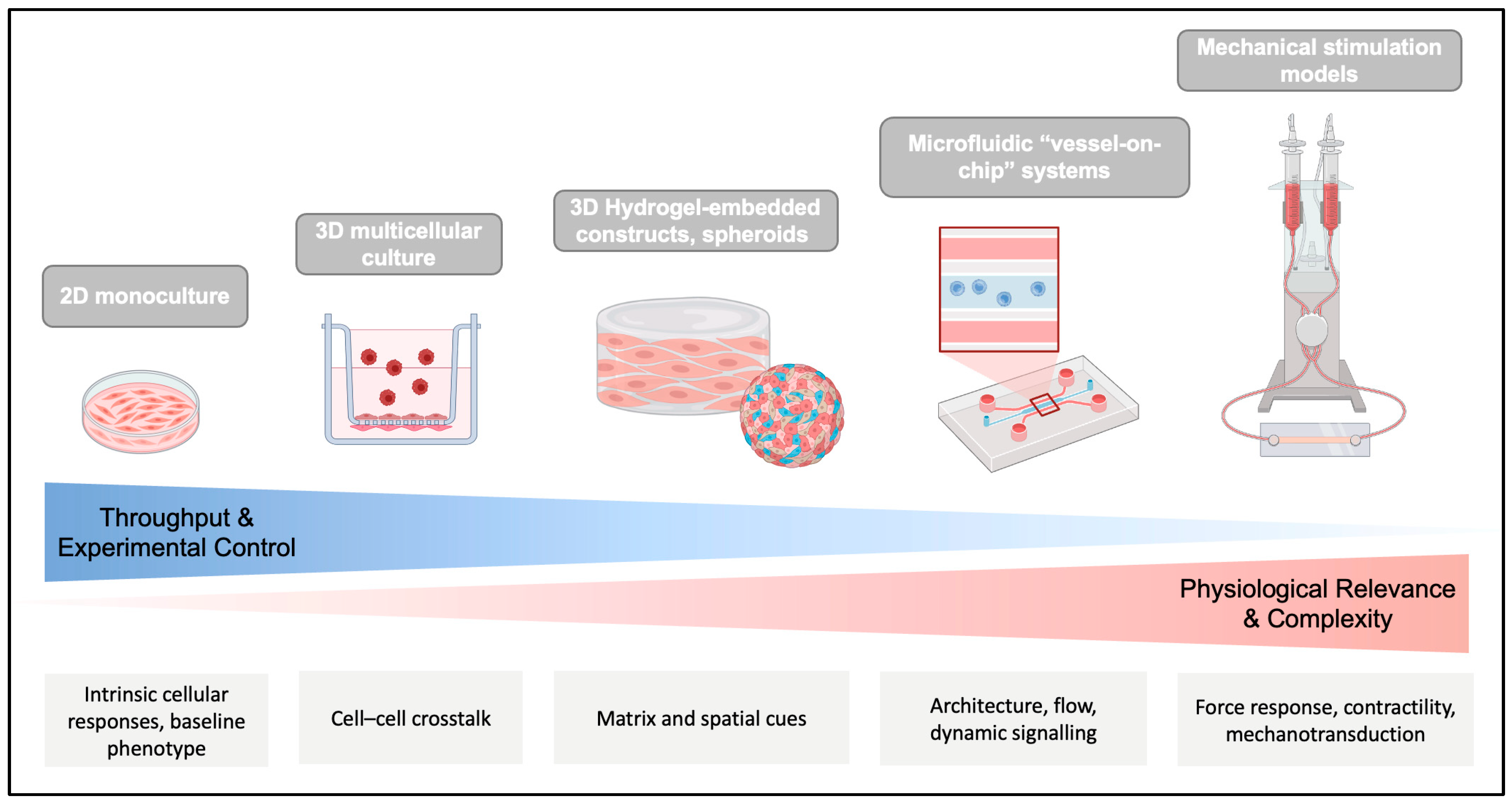

4. In Vitro Models of SMC Plasticity: From Monocultures to 3D Systems

4.1. What Makes a Good Model?

4.2. Simple Monocultures

4.3. Human iPSC-Derived SMCs

4.4. Co-Cultures

4.4.1. EC-SMC Co-Cultures

4.4.2. SMC–Immune Co-Cultures

4.4.3. EC–SMC–Immune Cell Tri-Cultures

4.5. 3D and Microfluidic Systems

4.5.1. Spheroids and Aggregates

4.5.2. Hydrogel-Embedded Constructs

4.5.3. Tissue-Engineered Vascular Constructs

4.5.4. Microfluidic “Vessel-on-Chip”

4.6. Mechanical Stimulation Models

4.6.1. Substrate Stiffness and Topology

4.6.2. Cyclic Stretch and Pressure

4.6.3. Shear and Transmural Flow

4.7. When Is Complexity Needed? When Is It Misleading?

| Model Type | Key Features/Rationale | Principal Strengths | Limitations | Optimal Applications | Representative Resources/ Key Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary SMC monocultures | Cultures of primary human or rodent SMCs under defined stimuli | Mechanistic clarity; precise control over variables; compatible with genetic (siRNA, CRISPR-Cas9) and pharmacological perturbations; scalable for high-throughput studies. | Rapid loss of contractile phenotype; donor variability and cost (human); species-specific divergence in lineage and signalling (rodent); absence of multicellular context. | Reductionist mechanistic studies; dissecting causal signalling pathways; screening and validation of regulators of the contractile-synthetic switch. | Chamley-Campbell et al., Physiol Rev 1979 [28]; Campbell et al., Clin Sci 1993 [148]; Chen et al., BMC Genomics 2016 [131] |

| Immortalised SMC lines | Continuous cell lines of rodent or human origin. | Highly reproducible; cost-effective; long-term culture; convenient for transfection and high-throughput assays. | Altered cytoskeletal organisation; low contractile marker expression; phenotypes deviate from primary cells; limited disease relevance. | Preliminary mechanistic screening; high-throughput assays when primary SMCs are unavailable. | Kennedy et al., Vasc Cell 2014 [151]; Mackenzie et al., Int J Mol Med 2011 [152] |

| Human iPSC-derived SMCs | Differentiation from iPSCs along mesodermal, neural-crest, or epicardial lineages to generate renewable organotypic human SMCs. | Human and patient-specific; genetically tractable; scalable; can capture genetic determinants of plasticity (e.g., Marfan, SVAS); compatible with organoid and microfluidic models. | Immature/foetal-like phenotype; incomplete cytoskeletal organisation; variable purity and lineage bias; maturity-dependent interpretation required. | Genetic and mechanistic studies; modelling patient-specific variation; integration into 3D, vascular-organ-on-chip, and tri-culture systems. | Kwartler et al., ATVB 2024 [154]; Cheung et al., Nat Protoc 2014 [156]; Wanjare et al., Cardiovasc Res 2013 [163] |

| EC–SMC co-cultures | Endothelial–SMC systems arranged in direct contact, Transwell, or conditioned-media configurations. | Preserve EC–SMC crosstalk via Notch/Jagged, PDGF, TGF-β, ET-1; maintain contractile phenotype under contact; model endothelial dysfunction and fibrous-cap regulation. | Media incompatibility; donor-matching complexity; membrane composition and pore size limit fidelity; limited longevity. | Investigating EC-driven modulation of SMC state; studying endothelial activation and paracrine vs. contact-dependent cues. | Truskey et al., Int J High Throughput Screen 2010 [171]; Liu et al., Circ Res 2009 [172]; Abbott et al., Journal of Vascular Surgery 1993 [134] |

| SMC–immune cell co-cultures | Bi-cultures with macrophages or T-cells in contact, insert-separated, or conditioned-media formats. | Enable study of inflammatory cues driving macrophage-like and osteogenic-like SMC states; replicate paracrine vs. juxtacrine regulation; align with plaque-derived signatures. | Lack endothelial barrier; immune-cell polarisation drift; use of immortalised lines (e.g., THP-1) may misrepresent primary cells; ratio imbalance can exaggerate effects. | Mechanistic dissection of inflammation-induced plasticity; validating cytokine- and lipid-driven transitions observed in vivo. | Weinert et al., Cardiovasc Res 2012 [181]; Schäfer et al., ATVB 2024 [185]; Deuell et al., J Vasc Res 2012 [188] |

| EC–SMC–immune cell tri-cultures | Three-cell Transwell or layered systems allowing endothelial activation, leukocyte transmigration, and SMC response. | Closest 2D analogue of plaque microenvironment; reproduces adhesion, barrier disruption, transmigration; recapitulates combined EC + immune cell cues inducing strong SMC phenotypic shifts. | Complex setup; ratio and insert variability; media matching and polarisation control critical; low throughput. | Modelling endothelial activation–immune cascade–SMC response axis; assessing multi-cellular inflammatory regulation of SMC fate. | Liu et al., PLOS ONE 2023 [143]; Wiejak et al., Scientific Reports 2023 [144]; Noonan et al., Front Immunol 2019 [145] |

| 3D spheroids/aggregates | Self-assembling SMC or mixed-cell clusters forming oxygen and matrix gradients. | Generate hypoxic cores and matrix gradients; enable contractility assays; support drug perturbation screening; reflect HIF-1α/RUNX2-driven osteogenic programmes. | Core-rim heterogeneity; undefined ECM composition on non-adherent substrates; diffusion constraints. | Studying hypoxia-dependent reprogramming, calcification-related transitions, and contractile function. | San Sebastián-Jaraba et al., Clin Investig Arterioscler 2024 [191]; da Silva Feltran et al., Exp Cell Res 2024 [192]; Garg et al., Cells 2023 [193] |

| Hydrogel-embedded constructs | SMCs or EC–SMC mixtures embedded in defined ECM hydrogels (e.g., PEG-fibrinogen, GelMA/alginate). | Tunable stiffness and composition; support mechanotransduction analysis; demonstrate stiffness-dependent phenotype (RhoA activation, MYOCD/MRTF response). | Gel composition, crosslinking, and stiffness strongly affect outcomes; limited scalability. | Testing stiffness- and matrix-composition-dependent regulation of SMC phenotype and viability. | Stegemann et al., J Appl Physiol 2005 [195]; Peyton et al., Biomaterials 2008 [196]; Xuan et al., Tissue Eng Regen Med 2023 [197] |

| Tissue-engineered vascular constructs | 3D rings/tubes with circumferential SMC alignment and optional EC/fibroblast layers. | Recapitulate geometry and flow; allow contractility testing (e.g., KCl-induced response); suitable for patient-specific iPSC-SMCs. | Technically demanding; requires bioreactors; low throughput. | Modelling flow and pressure effects on contractility and matrix deposition; translational disease modelling. | Dash et al., Stem Cell Reports 2016 [165]; Liu et al., Microsystems & Nanoeng 2025 [198] |

| Microfluidic “vessel-on-chip” systems | EC–SMC co-culture channels under laminar or disturbed flow in defined 3D ECM. | Real-time observation of EC activation and paracrine SMC modulation; captures shear-dependent phenotype switching; compatible with iPSC-derived cells. | Complex fabrication; lack of standardised metrics; limited duration. | Studying shear- and flow-dependent EC–SMC signalling; donor-specific vascular responses. | Vila Cuenca et al., Stem Cell Reports 2021 [170]; van Engeland et al., Lab Chip 2018 [199]; Liu et al., Lab on a Chip, 2023 [201] |

| Mechanical stimulation models (stretch, pressure, shear) | Systems applying cyclic strain (5–15%, 0.5–1 Hz), pressure, or shear flow to cultured SMCs or EC–SMC assemblies. | Quantitative control of mechanical cues; replicate pulsatile and disturbed hemodynamics; reveal activation of SRF–MYOCD/MRTF and YAP/TAZ pathways. | Require specialised equipment; simplified cellular context. | Mechanistic interrogation of mechanotransduction; coupling of mechanical and biochemical cues. | Tsai et al., Circ Res 2009 [209]; Kona et al., Open Biomed Eng J 2009 [207] |

5. Benchmarking Models Against Human Data

5.1. The Need for Human-Relevant Benchmarking

5.2. Role of Human Single-Cell Transcriptomics

5.3. GWAS and Genetic Risk as Tools for Model Prioritisation

5.4. Beyond Transcriptomics: Multi-Omic Integration

| Dataset Type | Representative Resources/ Key Studies | Principal Insights into SMC Phenotypes | Translational/Benchmarking Relevance | Notes/Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq (scRNA-seq/snRNA-seq) | Wirka et al., Nat Med 2019 [18]; Pan et al., Circulation 2020 [42]; Alencar et al., Circulation 2020 [47]; Depuydt et al., Circ Res 2022 [48] | Define discrete human SMC-derived phenotypes (fibromyocyte, intermediate, inflammatory, osteogenic-like); reveal vascular-bed-specific heterogeneity and transcriptional trajectories of modulation. | Provide a gold-standard framework for benchmarking model fidelity through label transfer, module scoring, and trajectory alignment. | Susceptible to dissociation and sampling bias; dominated by late-stage lesions; limited capture of early transitions. |

| Integrated single-cell plaque atlases | Traeuble et al., Nat Commun 2025 [222]; Mosquera et al., Cell Reports 2023 [50] | Combine >250 k cells across carotid, coronary, and femoral arteries to generate harmonised annotations of vascular cell states. | Enable cross-cohort and cross-species reference mapping; mitigate donor and arterial-bed bias for quantitative benchmarking. | Integration may blur cohort-specific nuances; limited spatial resolution. |

| Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and eQTL integration | Aragam et al., Nat Genet 2022 [224]; Kessler et al., JACC Basic Transl Sci 2021 [223]; van der Harst et al., Circ Res 2018 [245] | Identify CAD risk loci enriched in SMC-active enhancers; link variants to genes (TCF21, KLF4, SMAD3, PDGFD) that regulate SMC state transitions. | Support genetic prioritisation of pathways most relevant to human disease; guide target selection for perturbation studies. | Require colocalisation and perturbation validation; limited cell-state resolution. |

| Single-cell chromatin accessibility (scATAC-seq) | Aherrahrou et al., Circ Res 2023 [230]; Depuydt et al., Cir c Res 2022 [48]; Turner et al., Nat Genet 2022 [237]; Amrute et al., medRxiv 2024 [235] | Map enhancer landscapes and transcription-factor motif activity (e.g., KLF4, TCF21, JUN, TEAD), defining regulatory networks underlying SMC transitions. | Provide chromatin-level benchmarks connecting CAD variants to active enhancers and transcriptional programmes. | Sparse coverage per cell; donor and arterial heterogeneity; require integration with transcriptomic data. |

| Proteomic and CITE-seq datasets | Bashore et al., ATVB 2024 [238]; Theofilatos et al., Circ Res 2023 [239]; Lorentzen et al., Matrix Biol Plus 2024 [240]; Palm et al., Cardiovasc Res 2025 [241] | Identify post-transcriptional divergence; define SMC-derived subpopulations by surface proteins; link ECM remodelling, inflammation, and calcification to protein abundance. | Validate whether transcriptional programmes translate to protein-level changes; benchmark translational fidelity of models. | Lower proteomic depth than RNA; antibody and detection bias; RNA–protein discordance common. |

| Spatial transcriptomics and proteomics | Pauli et al., bioRxiv 2025 [242]; Campos et al., EMBO Mol Med 2025 [243]; Jokumsen et al., bioRxiv 2025 [244] | Localise transcriptionally defined SMC phenotypes within plaques; map zonation across intima, media, and adventitia; identify EC–immune–SMC interfaces. | Enable spatial benchmarking linking molecular states to anatomical regions; integrate morphology with molecular validation. | Resolution remains limited; most data derive from late-stage human lesions; high analytical cost and complexity. |

6. Implications for Modelling Disease and Therapeutic Discovery

6.1. Importance of Model Transparency and Reproducibility

6.2. Therapeutic Implications of Poorly Modelled States

6.3. The Future: Integrating Omics and Model Systems

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kawai, K.; Kawakami, R.; Finn, A.V.; Virmani, R. Differences in Stable and Unstable Atherosclerotic Plaque. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1474–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stary, H.C.; Chandler, A.B.; Dinsmore, R.E.; Fuster, V.; Glagov, S.; Insull, W.; Rosenfeld, M.E.; Schwartz, C.J.; Wagner, W.D.; Wissler, R.W. A Definition of Advanced Types of Atherosclerotic Lesions and a Histological Classification of Atherosclerosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1995, 15, 1512–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, R.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Burke, A.P.; Farb, A.; Schwartz, S.M. Lessons From Sudden Coronary Death. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 1262–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrington, W.; Lacey, B.; Sherliker, P.; Armitage, J.; Lewington, S. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.A. The Greatly Under-Represented Role of Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2023, 25, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiya, T.; Meganathan, I.; Ness, N.; Oudit, G.Y.; Murray, A.; Kassiri, Z. Contribution of the arterial cells to atherosclerosis and plaque formation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2024, 327, H804–H823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacakova, L.; Travnickova, M.; Filova, E.; Matějka, R.; Stepanovska, J.; Musilkova, J.; Zarubova, J.; Molitor, M. The Role of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in the Physiology and Pathophysiology of Blood Vessels. In Muscle Cell and Tissue—Current Status of Research Field; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.Y.; Chen, A.Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.F.; Kong, X.Q.; Zhang, J.J. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Phenotypic Switching in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majesky, M.W. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankman, L.S.; Gomez, D.; Cherepanova, O.A.; Salmon, M.; Alencar, G.F.; Haskins, R.M.; Swiatlowska, P.; Newman, A.A.C.; Greene, E.S.; Straub, A.C.; et al. KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Jacquet, L.; Karamariti, E.; Xu, Q. Origin and differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 3013–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rensen, S.S.; Doevendans, P.A.; van Eys, G.J. Regulation and characteristics of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic diversity. Neth. Heart J. 2007, 15, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Martin, K.A. TCF21: Flipping the Phenotypic Switch in SMC. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D.; Owens, G.K. Smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 95, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, J.L.; Jorgensen, H.F. The role of smooth muscle cells in plaque stability: Therapeutic targeting potential. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 3741–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, L.F.; Bentzon, J.F.; Albarran-Juarez, J. The Phenotypic Responses of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Exposed to Mechanical Cues. Cells 2021, 10, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, P.; Enkhjargal, B.; Manaenko, A.; Tang, J.; Pearce, W.J.; Hartman, R.; Obenaus, A.; Chen, G.; et al. Recombinant Osteopontin Stabilizes Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype via Integrin Receptor/Integrin-Linked Kinase/Rac-1 Pathway After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Stroke 2016, 47, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirka, R.C.; Wagh, D.; Paik, D.T.; Pjanic, M.; Nguyen, T.; Miller, C.L.; Kundu, R.; Nagao, M.; Coller, J.; Koyano, T.K.; et al. Atheroprotective roles of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and the TCF21 disease gene as revealed by single-cell analysis. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Lyu, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Wirka, R.C.; Bagga, J.; Nguyen, T.; Cheng, P.; Kim, J.B.; Pjanic, M.; Miano, J.M.; et al. Coronary Disease-Associated Gene TCF21 Inhibits Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation by Blocking the Myocardin-Serum Response Factor Pathway. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.J. FDA Modernization Act 2.0 allows for alternatives to animal testing. Artif. Organs 2023, 47, 449–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zushin, P.H.; Mukherjee, S.; Wu, J.C. FDA Modernization Act 2.0: Transitioning beyond animal models with human cells, organoids, and AI/ML-based approaches. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e175824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Shivnaraine, R.V.; Wu, J.C. FDA Modernization Act 2.0 Paves the Way to Computational Biology and Clinical Trials in a Dish. Circulation 2023, 148, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, P.; Jarr, K.-U.; Gomez, D.; Jørgensen, H.F.; Leeper, N.J.; Bochaton-Piallat, M.-L. Smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis: Essential but overlooked translational perspectives. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4862–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalli, O.; Ropraz, P.; Trzeciak, A.; Benzonana, G.; Gillessen, D.; Gabbiani, G. A monoclonal antibody against alpha-smooth muscle actin: A new probe for smooth muscle differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 103, 2787–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Miano, J.M.; Cserjesi, P.; Olson, E.N. SM22 alpha, a marker of adult smooth muscle, is expressed in multiple myogenic lineages during embryogenesis. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Nadal-Ginard, B. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of smooth muscle calponin. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 13284–13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, M.; Sivam, P.N.; Kuro-o, M.; Kimura, K.; Nakahara, K.; Takewaki, S.; Ueda, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Yazaki, Y.; Periasamy, M.; et al. Human smooth muscle myosin heavy chain isoforms as molecular markers for vascular development and atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 1993, 73, 1000–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamley-Campbell, J.; Campbell, G.R.; Ross, R. The smooth muscle cell in culture. Physiol. Rev. 1979, 59, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, R.S.; Thompson, M.M.; Owens, G.K. Cell cycle versus density dependence of smooth muscle alpha actin expression in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corjay, M.H.; Thompson, M.M.; Lynch, K.R.; Owens, G.K. Differential Effect of Platelet-derived Growth Factor- Versus Serum-induced Growth on Smooth Muscle α-Actin and Nonmuscle β-Actin mRNA Expression in Cultured Rat Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 10501–10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Xuan, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Jin, H.; Dong, H. How vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype switching contributes to vascular disease. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.; Mieremet, A.; de Vries, C.J.M.; Micha, D.; de Waard, V. Six Shades of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Illuminated by KLF4 (Kruppel-Like Factor 4). Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2693–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokin, V.; Vickneson, K.; Kofidis, T.; Woo, C.C.; Lin, X.Y.; Foo, R.; Shanahan, C.M. Role of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Plasticity and Interactions in Vessel Wall Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 599415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Gomez, D. Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Diversity. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 1715–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Chatterjee, P.; Dave, J.M.; Ostriker, A.C.; Greif, D.M.; Rzucidlo, E.M.; Martin, K.A. Targeting smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in vascular disease. JVS Vasc. Sci. 2021, 2, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühbandner, S.; Brummer, S.; Metzger, D.; Chambon, P.; Hofmann, F.; Feil, R. Temporally controlled somatic mutagenesis in smooth muscle. Genesis 2000, 28, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfsgruber, W.; Feil, S.; Brummer, S.; Kuppinger, O.; Hofmann, F.; Feil, R. A proatherogenic role for cGMP-dependent protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13519–13524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadelaar, S.M.; Boesten, L.S.; Pires, N.M.; van Nieuwkoop, A.; Biessen, E.A.; Jukema, W.; Havekes, L.M.; van Vlijmen, B.J.; Willems van Dijk, K. Local Cre-mediated gene recombination in vascular smooth muscle cells in mice. Transgenic Res. 2006, 15, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendling, O.; Bornert, J.-M.; Chambon, P.; Metzger, D. Efficient temporally-controlled targeted mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells of the adult mouse. Genesis 2009, 47, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Li, C.; Frieler, R.A.; Gerasimova, A.S.; Lee, S.J.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.M.; Lumeng, C.N.; Brosius, F.C.; Duan, S.Z.; et al. Smooth muscle protein 22 alpha-Cre is expressed in myeloid cells in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 422, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, R.; Saddouk, F.Z.; Carrao, A.C.; Krause, D.S.; Greif, D.M.; Martin, K.A. Promoters to Study Vascular Smooth Muscle. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Xue, C.; Auerbach, B.J.; Fan, J.; Bashore, A.C.; Cui, J.; Yang, D.Y.; Trignano, S.B.; Liu, W.; Shi, J.; et al. Single-Cell Genomics Reveals a Novel Cell State During Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Switching and Potential Therapeutic Targets for Atherosclerosis in Mouse and Human. Circulation 2020, 142, 2060–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Dubland, J.A.; Allahverdian, S.; Asonye, E.; Sahin, B.; Jaw, J.E.; Sin, D.D.; Seidman, M.A.; Leeper, N.J.; Francis, G.A. Smooth Muscle Cells Contribute the Majority of Foam Cells in ApoE (Apolipoprotein E)-Deficient Mouse Atherosclerosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.; Jørgensen, H.F. Epigenetic regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2025, 401, 119085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M.C.; Figg, N.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P.; Goddard, M.; Littlewood, T.D.; Bennett, M.R. Apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells induces features of plaque vulnerability in atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzon, J.F.; Majesky, M.W. Lineage tracking of origin and fate of smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, G.F.; Owsiany, K.M.; Karnewar, S.; Sukhavasi, K.; Mocci, G.; Nguyen, A.T.; Williams, C.M.; Shamsuzzaman, S.; Mokry, M.; Henderson, C.A.; et al. Stem Cell Pluripotency Genes Klf4 and Oct4 Regulate Complex SMC Phenotypic Changes Critical in Late-Stage Atherosclerotic Lesion Pathogenesis. Circulation 2020, 142, 2045–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depuydt, M.A.C.; Prange, K.H.M.; Slenders, L.; Örd, T.; Elbersen, D.; Boltjes, A.; de Jager, S.C.A.; Asselbergs, F.W.; de Borst, G.J.; Aavik, E.; et al. Microanatomy of the Human Atherosclerotic Plaque by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1437–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Diez, C.; Mandi, V.; Du, M.; Liu, M.; Gomez, D. Smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis: Clones but not carbon copies. JVS Vasc. Sci. 2021, 2, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, J.V.; Auguste, G.; Wong, D.; Turner, A.W.; Hodonsky, C.J.; Alvarez-Yela, A.C.; Song, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Lino Cardenas, C.L.; Theofilatos, K.; et al. Integrative single-cell meta-analysis reveals disease-relevant vascular cell states and markers in human atherosclerosis. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Weiser-Evans, M.C.M. Lgals3-Transitioned Inflammatory Smooth Muscle Cells: Major Regulators of Atherosclerosis Progression and Inflammatory Cell Recruitment. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Kwartler, C.S.; Kaw, K.; Li, Y.; Kaw, A.; Chen, J.; LeMaire, S.A.; Shen, Y.H.; Milewicz, D.M. Cholesterol-Induced Phenotypic Modulation of Smooth Muscle Cells to Macrophage/Fibroblast–like Cells Is Driven by an Unfolded Protein Response. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Han, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, L.; Wang, L.; Lui, K.O.; He, B.; Zhou, B. Smooth muscle-derived macrophage-like cells contribute to multiple cell lineages in the atherosclerotic plaque. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allahverdian, S.; Chehroudi, A.C.; McManus, B.M.; Abraham, T.; Francis, G.A. Contribution of Intimal Smooth Muscle Cells to Cholesterol Accumulation and Macrophage-Like Cells in Human Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2014, 129, 1551–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaigh, T.; Evans, D.; Frankel, D.; Torkamani, A. Decoding the transcriptome of calcified atherosclerotic plaque at single-cell resolution. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, M.Y.; Yang, H.Y.; Brabb, T.; Leaf, E.; Look, A.; Lin, W.L.; Frutkin, A.; Dichek, D.; Giachelli, C.M. Smooth muscle cells give rise to osteochondrogenic precursors and chondrocytes in calcifying arteries. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Byon, C.H.; Yuan, K.; Chen, J.; Mao, X.; Heath, J.M.; Javed, A.; Zhang, K.; Anderson, P.G.; Chen, Y. Smooth muscle cell-specific Runx2 deficiency inhibits vascular calcification. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ji, G.; Shen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, L. SOX9 and myocardin counteract each other in regulating vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 422, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, I.; Owens, G.K. Recruitment of Serum Response Factor and Hyperacetylation of Histones at Smooth Muscle–Specific Regulatory Regions During Differentiation of a Novel P19-Derived In Vitro Smooth Muscle Differentiation System. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoretti-Mercado, B.; Dulin, N.O.; Solway, J. SRF Function in Vascular Smooth Muscle. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arsenian, S.; Weinhold, B.; Oelgeschläger, M.; Rüther, U.; Nordheim, A. Serum response factor is essential for mesoderm formation during mouse embryogenesis. Embo J. 1998, 17, 6289–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletti, D.; Daou, N.; Hassani, M.; Li, Z.; Parlakian, A. Serum Response Factor in Muscle Tissues: From Development to Ageing. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2016, 26, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landerholm, T.E.; Dong, X.R.; Lu, J.; Belaguli, N.S.; Schwartz, R.J.; Majesky, M.W. A role for serum response factor in coronary smooth muscle differentiation from proepicardial cells. Development 1999, 126, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan-Albuquerque, N.; Van Putten, V.; Weiser-Evans, M.C.; Nemenoff, R.A. Depletion of serum response factor by RNA interference mimics the mitogenic effects of platelet derived growth factor-BB in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, D.; Grassi, G.; Konjer, N.; Dapas, B.; Farra, R.; Giansante, C.; Kandolf, R.; Guarnieri, G.; Nordheim, A.; Heidenreich, O. Proliferation of human primary vascular smooth muscle cells depends on serum response factor. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 89, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, D.Z.; Pipes, G.C.; Olson, E.N. Myocardin is a master regulator of smooth muscle gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7129–7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmacek, M.S. Myocardin: Dominant driver of the smooth muscle cell contractile phenotype. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1416–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, C.P.; Hinson, J.S. Regulation of smooth muscle differentiation by the myocardin family of serum response factor co-factors. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 1976–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, X.; Bell, R.D.; Gerthoffer, W.T.; Zlokovic, B.V.; Miano, J.M. Myocardin is sufficient for a smooth muscle-like contractile phenotype. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphel, L.; Talasila, A.; Cheung, C.; Sinha, S. Myocardin Overexpression Is Sufficient for Promoting the Development of a Mature Smooth Muscle Cell-Like Phenotype from Human Embryonic Stem Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackers-Johnson, M.; Talasila, A.; Sage, A.P.; Long, X.; Bot, I.; Morrell, N.W.; Bennett, M.R.; Miano, J.M.; Sinha, S. Myocardin Regulates Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Inflammatory Activation and Disease. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, T.; Wright, A.C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, S.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Small, A.; Parmacek, M.S. Myocardin is required for maintenance of vascular and visceral smooth muscle homeostasis during postnatal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4447–4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Chen, M.; Zhou, D.; Lu, M.M.; Proweller, A.; Epstein, J.A.; Parmacek, M.S. Myocardin regulates expression of contractile genes in smooth muscle cells and is required for closure of the ductus arteriosus in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschka, S.D. Myocardin: A Novel Potentiator of SRF-Mediated Transcription in Cardiac Muscle. Molecular Cell 2001, 8, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipes, G.C.; Creemers, E.E.; Olson, E.N. The myocardin family of transcriptional coactivators: Versatile regulators of cell growth, migration, and myogenesis. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-Z.; Li, S.; Hockemeyer, D.; Sutherland, L.; Wang, Z.; Schratt, G.; Richardson, J.A.; Nordheim, A.; Olson, E.N. Potentiation of serum response factor activity by a family of myocardin-related transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 14855–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouilleron, S.; Guettler, S.; Langer, C.A.; Treisman, R.; McDonald, N.Q. Molecular basis for G-actin binding to RPEL motifs from the serum response factor coactivator MAL. Embo J. 2008, 27, 3198–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, F.; Posern, G.; Zaromytidou, A.-I.; Treisman, R. Actin Dynamics Control SRF Activity by Regulation of Its Coactivator MAL. Cell 2003, 113, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, P.; Kofler, M.; Szászi, K.; Kapus, A. Context-dependent switch in chemo/mechanotransduction via multilevel crosstalk among cytoskeleton-regulated MRTF and TAZ and TGFβ-regulated Smad3. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Richardson, J.A.; Olson, E.N. Requirement of myocardin-related transcription factor-B for remodeling of branchial arch arteries and smooth muscle differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15122–15127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, M.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, D.; Lu, M.M.; Du, K.; Epstein, J.A.; Parmacek, M.S. Myocardin-related transcription factor B is required in cardiac neural crest for smooth muscle differentiation and cardiovascular development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8916–8921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Li, N.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, R.; Zhao, H.; Fan, Z.; Zhuo, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y. MKL1 fuels ROS-induced proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells by modulating FOXM1 transcription. Redox Biol. 2023, 59, 102586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, T.; Kuwahara, K.; Nakagawa, Y.; Takaoka, M.; Kinoshita, H.; Nakao, K.; Kuwabara, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Yamada, C.; Shibata, J.; et al. Reciprocal expression of MRTF-A and myocardin is crucial for pathological vascular remodelling in mice. Embo J. 2012, 31, 4428–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creemers, E.E.; Sutherland, L.B.; McAnally, J.; Richardson, J.A.; Olson, E.N. Myocardin is a direct transcriptional target of Mef2, Tead and Foxo proteins during cardiovascular development. Development 2006, 133, 4245–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potthoff, M.J.; Olson, E.N. MEF2: A central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development 2007, 134, 4131–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, J.; Ma, P.X.; Chen, Y.E. Yap1 protein regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic switch by interaction with myocardin. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 14598–14605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo Martínez, M.; Ritsvall, O.; Bastrup, J.A.; Celik, S.; Jakobsson, G.; Daoud, F.; Winqvist, C.; Aspberg, A.; Rippe, C.; Maegdefessel, L.; et al. Vascular smooth muscle–specific YAP/TAZ deletion triggers aneurysm development in mouse aorta. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e170845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, L.T.; Norton, C.R.; Gridley, T. Notch signal reception is required in vascular smooth muscle cells for ductus arteriosus closure. Genesis 2016, 54, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.; Guha, S.; Sweeney, C.; Birney, Y.; Walshe, T.; O’Brien, C.; Walls, D.; Redmond, E.M.; Cahill, P.A. Notch and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotype. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 1370–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenga, V.; Fardoux, P.; Lacombe, P.; Monet, M.; Maciazek, J.; Krebs, L.T.; Klonjkowski, B.; Berrou, E.; Mericskay, M.; Li, Z.; et al. Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2730–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, H.; Hasegawa, K.; Morimoto, T.; Kakita, T.; Yanazume, T.; Sasayama, S. A p300 Protein as a Coactivator of GATA-6 in the Transcription of the Smooth Muscle-Myosin Heavy Chain Gene*. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 25330–25335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Merenick, B.L.; Ding, M.; Fetalvero, K.M.; Wagner, R.J.; Mai, A.; Gleim, S.; Tucker, D.F.; Birnbaum, M.J.; et al. Phosphorylation of GATA-6 is required for vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation after mTORC1 inhibition. Sci. Signal. 2015, 8, ra44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sinha, S.; McDonald, O.G.; Shang, Y.; Hoofnagle, M.H.; Owens, G.K. Kruppel-like factor 4 abrogates myocardin-induced activation of smooth muscle gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 9719–9727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidkovka, N.A.; Cherepanova, O.A.; Yoshida, T.; Alexander, M.R.; Deaton, R.A.; Thomas, J.A.; Leitinger, N.; Owens, G.K. Oxidized phospholipids induce phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.S.; Starke, R.M.; Jabbour, P.M.; Tjoumakaris, S.I.; Gonzalez, L.F.; Rosenwasser, R.H.; Owens, G.K.; Koch, W.J.; Greig, N.H.; Dumont, A.S. TNF-α induces phenotypic modulation in cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells: Implications for cerebral aneurysm pathology. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.L.; Anderson, D.R.; Kundu, R.K.; Raiesdana, A.; Nürnberg, S.T.; Diaz, R.; Cheng, K.; Leeper, N.J.; Chen, C.-H.; Chang, I.S.; et al. Disease-Related Growth Factor and Embryonic Signaling Pathways Modulate an Enhancer of TCF21 Expression at the 6q23.2 Coronary Heart Disease Locus. PLOS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurnberg, S.T.; Cheng, K.; Raiesdana, A.; Kundu, R.; Miller, C.L.; Kim, J.B.; Arora, K.; Carcamo-Oribe, I.; Xiong, Y.; Tellakula, N.; et al. Coronary Artery Disease Associated Transcription Factor TCF21 Regulates Smooth Muscle Precursor Cells That Contribute to the Fibrous Cap. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, C.P. Signaling Mechanisms That Regulate Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, O.G.; Owens, G.K. Programming Smooth Muscle Plasticity With Chromatin Dynamics. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, D.Z.; Hockemeyer, D.; McAnally, J.; Nordheim, A.; Olson, E.N. Myocardin and ternary complex factors compete for SRF to control smooth muscle gene expression. Nature 2004, 428, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Hu, G.; Herring, B.P. Smooth muscle-specific genes are differentially sensitive to inhibition by Elk-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 9874–9885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Liu, M.; Yao, X.; Hao, W.; Ma, J.; Ren, Y.; Gao, X.; Xin, L.; Ge, L.; Yu, Y.; et al. Vascular injury activates the ELK1/SND1/SRF pathway to promote vascular smooth muscle cell proliferative phenotype and neointimal hyperplasia. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanova, O.A.; Gomez, D.; Shankman, L.S.; Swiatlowska, P.; Williams, J.; Sarmento, O.F.; Alencar, G.F.; Hess, D.L.; Bevard, M.H.; Greene, E.S.; et al. Activation of the pluripotency factor OCT4 in smooth muscle cells is atheroprotective. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Tkachenko, S.; Gomez, D.; Tripathi, R.; Owens, G.K.; Cherepanova, O.A. Smooth muscle cells-specific loss of OCT4 accelerates neointima formation after acute vascular injury. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1276945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Qin, Y. OCT4 regulated neointimal formation in injured mouse arteries by matrix metalloproteinase 2-mediated smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 5421–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, A.L.; Yao, W.; Remillard, C.V.; Ogawa, A.; Yuan, J.X. Upregulation of Oct-4 isoforms in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010, 298, L548–L557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, J.M.; Fisher, E.A.; Majesky, M.W. Fate and State of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2021, 143, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleeva, M.; Ahmad, S.; Theofilatos, K.; Lynham, S.; Watson, G.; Whitehead, M.; Marhuenda, E.; Iskratsch, T.; Cox, S.; Shanahan, C.M. Sox9 Accelerates Vascular Aging by Regulating Extracellular Matrix Composition and Stiffness. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedin, U.; Bottger, B.A.; Forsberg, E.; Johansson, S.; Thyberg, J. Diverse effects of fibronectin and laminin on phenotypic properties of cultured arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyberg, J.; Blomgren, K.; Roy, J.; Tran, P.K.; Hedin, U. Phenotypic Modulation of Smooth Muscle Cells after Arterial Injury Is Associated with Changes in the Distribution of Laminin and Fibronectin. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1997, 45, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedin, U.; Thyberg, J. Plasma fibronectin promotes modulation of arterial smooth-muscle cells from contractile to synthetic phenotype. Differentiation 1987, 33, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Kazi, M.; Hedin, U.; Thyberg, J. Phenotypic modulation of arterial smooth muscle cells is associated with prolonged activation of ERK1/2. Differentiation 2001, 67, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.J.; Millis, A.J.; Fritz, K.E. Fibronectin Inhibits Morphological Changes in Cultures of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1982, 112, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, J.H.-N.A. Fibronectin and the basement membrane components laminin and collagen type IV influence the phenotypic properties of subcultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells differently. Cell Tissue Res. 1994, 276, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenseil, J.E.; Mecham, R.P. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 957–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, J.C.; Lampi, M.C.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Age-related vascular stiffening: Causes and consequences. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, R.; Horn, N.; Selg, M.; Wendler, O.; Pausch, F.; Sorokin, L.M. Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 979–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenco, P.D. Basement membranes: Cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a004911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittig, C.; Szulcek, R. Extracellular Matrix Protein Ratios in the Human Heart and Vessels: How to Distinguish Pathological From Physiological Changes? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 708656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, A.W.; Lee, M.Y.; Lemmon, J.A.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Gomez, M.F.; Bortz, P.D.; Wamhoff, B.R. Molecular mechanisms of collagen isotype-specific modulation of smooth muscle cell phenotype. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Cui, T.; Mills, D.K.; Lvov, Y.M.; McShane, M.J. Comparison of selective attachment and growth of smooth muscle cells on gelatin- and fibronectin-coated micropatterns. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005, 5, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickel, A.P.; Sanyour, H.J.; Leyda, N.A.; Hong, Z. Extracellular Matrix Proteins and Substrate Stiffness Synergistically Regulate Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Migration and Cortical Cytoskeleton Organization. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 2360–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldin, C.-H.; Westermark, B. Mechanism of Action and In Vivo Role of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 1283–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.S.; Owens, G.K. Platelet-derived growth factor regulates actin isoform expression and growth state in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1990, 142, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrae, J.; Gallini, R.; Betsholtz, C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1276–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, G.K.; Kumar, M.S.; Wamhoff, B.R. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 767–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedin, U.; Roy, J.; Tran, P.K. Control of smooth muscle cell proliferation in vascular disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2004, 15, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Khan, F.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Seungjoon, M.; Park, M.N.; Kim, B. New insights about the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway as a promising target to develop cancer therapeutic strategies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérit, E.; Arts, F.; Dachy, G.; Boulouadnine, B.; Demoulin, J.-B. PDGF receptor mutations in human diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3867–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Tang, X.-Y.; Qu, Z.-Y.; Sun, Z.-W.; Ji, C.-F.; Li, Y.-J.; Guo, S.-D. Targeting the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway for cancer therapy: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cui, X.; Qian, Z.; Li, Y.; Kang, K.; Qu, J.; Li, L.; Gou, D. Multi-omics analysis reveals regulators of the response to PDGF-BB treatment in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Murgai, M.; Moehle, C.W.; Owens, G.K. Interleukin-1β modulates smooth muscle cell phenotype to a distinct inflammatory state relative to PDGF-DD via NF-κB-dependent mechanisms. Physiol. Genom. 2012, 44, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.M.; Fillinger, M.F.; O’Connor, S.E.; Wagner, R.J. The effect of endothelial cell coculture on smooth muscle cell proliferation. J. Vasc. Surg. 1993, 17, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarkhan-Hagvall, S.; Helenius, G.; Johansson, B.R.; Li, J.Y.; Mattsson, E.; Risberg, B. Co-culture of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells affects gene expression of angiogenic factors. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 89, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.L.; Babensee, J.E. Complimentary endothelial cell/smooth muscle cell co-culture systems with alternate smooth muscle cell phenotypes. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 35, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, C.S.; Truskey, G.A. Direct-contact co-culture between smooth muscle and endothelial cells inhibits TNF-alpha-mediated endothelial cell activation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H338–H346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; García-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiellaro, K.; Taylor, W.R. The role of the adventitia in vascular inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 75, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, E.L.; Aw, W.Y.; Hickey, A.J.; Polacheck, W.J. Microfluidic and Organ-on-a-Chip Approaches to Investigate Cellular and Microenvironmental Contributions to Cardiovascular Function and Pathology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 624435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middelkamp, H.H.; van den Berg, A.; van der Meer, A.D. Blood Vessels-on-Chip for atherosclerosis modelling. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Miniaturized Systems for Chemistry and Life Sciences, Palm Springs, CA, USA, 10–14 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Barbero, N.; Gutiérrez-Muñoz, C.; Blanco-Colio, L.M. Cellular Crosstalk between Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells in Vascular Wall Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Samant, S.; Vasa, C.H.; Pedrigi, R.M.; Oguz, U.M.; Ryu, S.; Wei, T.; Anderson, D.R.; Agrawal, D.K.; Chatzizisis, Y.S. Co-culture models of endothelial cells, macrophages, and vascular smooth muscle cells for the study of the natural history of atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiejak, J.; Murphy, F.A.; Maffia, P.; Yarwood, S.J. Vascular smooth muscle cells enhance immune/vascular interplay in a 3-cell model of vascular inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, J.; Grassia, G.; MacRitchie, N.; Garside, P.; Guzik, T.J.; Bradshaw, A.C.; Maffia, P. A Novel Triple-Cell Two-Dimensional Model to Study Immune-Vascular Interplay in Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, R.A.; Leopoldi, A.; Aichinger, M.; Kerjaschki, D.; Penninger, J.M. Generation of blood vessel organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 3082–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.R.; Sinha, S.; Owens, G.K. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.H.; Campbell, G.R. Culture techniques and their applications to studies of vascular smooth muscle. Clin. Sci. 1993, 85, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beamish, J.A.; Geyer, L.C.; Haq-Siddiqi, N.A.; Kottke-Marchant, K.; Marchant, R.E. The effects of heparin releasing hydrogels on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6286–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.R.; Owens, G.K. Epigenetic control of smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic switching in vascular development and disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2012, 74, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, E.; Hakimjavadi, R.; Greene, C.; Mooney, C.J.; Fitzpatrick, E.; Collins, L.E.; Loscher, C.E.; Guha, S.; Morrow, D.; Redmond, E.M.; et al. Embryonic rat vascular smooth muscle cells revisited—A model for neonatal, neointimal SMC or differentiated vascular stem cells? Vasc. Cell 2014, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, N.C.; Zhu, D.; Longley, L.; Patterson, C.S.; Kommareddy, S.; MacRae, V.E. MOVAS-1 cell line: A new in vitro model of vascular calcification. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 27, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Limor, R.; Kaplan, M.; Sawamura, T.; Sharon, O.; Keidar, S.; Weisinger, G.; Knoll, E.; Naidich, M.; Stern, N. Angiotensin II increases the expression of lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 in human vascular smooth muscle cells via a lipoxygenase-dependent pathway. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005, 18, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kwartler, C.S.; Esparza Pinelo, J.E. Use of iPSC-Derived Smooth Muscle Cells to Model Physiology and Pathology. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1523–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, M.; Reich, D.H.; Boheler, K.R. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived vascular smooth muscle cells. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 2, R1–R15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.; Bernardo, A.S.; Pedersen, R.A.; Sinha, S. Directed differentiation of embryonic origin-specific vascular smooth muscle subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Liu, C.; Wu, J.C. Generation of Embryonic Origin-Specific Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2429, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Xiong, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Qiu, P.; Hirai, H.; Shao, L.; Milewicz, D.; Chen, Y.E.; Yang, B. Differentiation defect in neural crest-derived smooth muscle cells in patients with aortopathy associated with bicuspid aortic valves. EBioMedicine 2016, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, G.; Marquez, H.A.; Yang, C.; Wong, J.Y.; Kotton, D.N. Generation of a Purified iPSC-Derived Smooth Muscle-like Population for Cell Sheet Engineering. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 13, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; McIntosh, B.E.; Wang, B.; Brown, M.E.; Probasco, M.D.; Webster, S.; Duffin, B.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.W.; Burlingham, W.J.; et al. A Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Based Screen for Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation and Maturation Identifies Inhibitors of Intimal Hyperplasia. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D. iPSCs-based generation of vascular cells: Reprogramming approaches and applications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 1411–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drab, M.; Haller, H.; Bychkov, R.; Erdmann, B.; Lindschau, C.; Haase, H.; Morano, I.; Luft, F.C.; Wobus, A.M. From totipotent embryonic stem cells to spontaneously contracting smooth muscle cells: A retinoic acid and db-cAMP in vitro differentiation model. Faseb J. 1997, 11, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjare, M.; Kuo, F.; Gerecht, S. Derivation and maturation of synthetic and contractile vascular smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 97, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsch, C.; Challet-Meylan, L.; Thoma, E.C.; Urich, E.; Heckel, T.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Grainger, S.J.; Kapp, F.G.; Sun, L.; Christensen, K.; et al. Generation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, B.C.; Levi, K.; Schwan, J.; Luo, J.; Bartulos, O.; Wu, H.; Qiu, C.; Yi, T.; Ren, Y.; Campbell, S.; et al. Tissue-Engineered Vascular Rings from Human iPSC-Derived Smooth Muscle Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2016, 7, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, A.; Serrano, F.; Bernard, W.G.; McNamara, M.; Low, L.; Sastry, P.; Sinha, S. An iPSC-derived vascular model of Marfan syndrome identifies key mediators of smooth muscle cell death. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Ren, Y.; Bartulos, O.; Lee, M.Y.; Yue, Z.; Kim, K.-Y.; Li, W.; Amos, P.J.; Bozkulak, E.C.; Iyer, A.; et al. Modeling Supravalvular Aortic Stenosis Syndrome With Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Circulation 2012, 126, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Landau, S.; Perera, K.; Lee, J.; Radisic, M. Engineering Organ-on-a-Chip Systems for Vascular Diseases. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Vila Cuenca, M.; de Graaf, M.; van den Hil, F.E.; Mummery, C.L.; Orlova, V.V. Three-Dimensional Vessels-on-a-Chip Based on hiPSC-derived Vascular Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila Cuenca, M.; Cochrane, A.; van den Hil, F.E.; de Vries, A.A.F.; Lesnik Oberstein, S.A.J.; Mummery, C.L.; Orlova, V.V. Engineered 3D vessel-on-chip using hiPSC-derived endothelial- and vascular smooth muscle cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truskey, G.A. Endothelial Cell Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Co-Culture Assay For High Throughput Screening Assays For Discovery of Anti-Angiogenesis Agents and Other Therapeutic Molecules. Int. J. High Throughput Screen. 2010, 2010, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kennard, S.; Lilly, B. NOTCH3 Expression Is Induced in Mural Cells Through an Autoregulatory Loop That Requires Endothelial-Expressed JAGGED1. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Roszell, E.E.; Sandig, M.; Mequanint, K. The role of endothelial cell-bound Jagged1 in Notch3-induced human coronary artery smooth muscle cell differentiation. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2462–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y.S.; Nguyen, P.; Wang, K.C.; Weiss, A.; Kuo, Y.C.; Chiu, J.J.; Shyy, J.Y.; Chien, S. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell turnover by endothelial cell-secreted microRNA-126: Role of shear stress. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Rauer, S.B.; Möller, M.; Singh, S. Mimicking the Natural Basement Membrane for Advanced Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 3081–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, C.; Redondo, J.; Rodríguez-Martínez, M.A.; Angulo, J.; Marín, J.; Sánchez-Ferrer, C.F. Influence of Endothelium on Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. Hypertension 1995, 25, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, S.M.; Campos, M.J.; Haystead, T.; Thompson, M.M.; DiCorleto, P.E.; Owens, G.K. Endothelial cell-conditioned medium downregulates smooth muscle contractile protein expression. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, C582–C591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Singh, N. Generation of Patterned Cocultures in 2D and 3D: State of the Art. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 34249–34261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J.; Liao, Y.; Yang, P.; Huang, N. Co-culture of endothelial cells and patterned smooth muscle cells on titanium: Construction with high density of endothelial cells and low density of smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 456, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butoi, E.D.; Gan, A.M.; Manduteanu, I.; Stan, D.; Calin, M.; Pirvulescu, M.; Koenen, R.R.; Weber, C.; Simionescu, M. Cross talk between smooth muscle cells and monocytes/activated monocytes via CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis augments expression of pro-atherogenic molecules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2011, 1813, 2026–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinert, S.; Poitz, D.M.; Auffermann-Gretzinger, S.; Eger, L.; Herold, J.; Medunjanin, S.; Schmeisser, A.; Strasser, R.H.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C. The lysosomal transfer of LDL/cholesterol from macrophages into vascular smooth muscle cells induces their phenotypic alteration. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 97, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayagopal, P.; Glancy, D.L. Macrophages Stimulate Cholesteryl Ester Accumulation in Cocultured Smooth Muscle Cells Incubated With Lipoprotein-Proteoglycan Complex. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Luo, M.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Shen, J.; Zhu, W.; Huang, L.; Hu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Macrophages regulate vascular smooth muscle cell function during atherosclerosis progression through IL-1β/STAT3 signaling. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Hojo, Y.; Ikeda, U.; Takahashi, M.; Shimada, K. Interaction between monocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells enhances matrix metalloproteinase-1 production. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000, 36, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, S.; Gogiraju, R.; Rösch, M.; Kerstan, Y.; Beck, L.; Garbisch, J.; Saliba, A.-E.; Gisterå, A.; Hermanns, H.M.; Boon, L.; et al. CD8+ T Cells Drive Plaque Smooth Muscle Cell Dedifferentiation in Experimental Atherosclerosis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 1852–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Lanting, L.; Natarajan, R. Interaction of Monocytes With Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Regulates Monocyte Survival and Differentiation Through Distinct Pathways. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarie, R.D.; Vadana, M.; Ciortan, L.; Tucureanu, M.M.; Ciobanu, A.; Vinereanu, D.; Manduteanu, I.; Simionescu, M.; Butoi, E. The expression of MMP-1 and MMP-9 is up-regulated by smooth muscle cells after their cross-talk with macrophages in high glucose conditions. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 4366–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuell, K.A.; Callegari, A.; Giachelli, C.M.; Rosenfeld, M.E.; Scatena, M. RANKL enhances macrophage paracrine pro-calcific activity in high phosphate-treated smooth muscle cells: Dependence on IL-6 and TNF-α. J. Vasc. Res. 2012, 49, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarie, R.D.; Tucureanu, M.M.; Ciortan, L.; Gan, A.-M.; Butoi, E.; Mânduțeanu, I. Ficolin-2 amplifies inflammation in macrophage-smooth muscle cell cross-talk and increases monocyte transmigration by mechanisms involving IL-1β and IL-6. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-C.; Sung, M.-L.; Kuo, H.-C.; Chien, S.-J.; Yen, C.-K.; Chen, C.-N. Differential Regulation of Human Aortic Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation by Monocyte-Derived Macrophages from Diabetic Patients. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Sebastián-Jaraba, I.; Fernández-Gómez, M.J.; Blázquez-Serra, R.; Sanz-Andrea, S.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Méndez-Barbero, N. In vitro 3D co-culture model of human endothelial and smooth muscle cells to study pathological vascular remodeling. Clínica E Investig. En Arterioscler. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 36, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Feltran, G.; Augusto da Silva, R.; da Costa Fernandes, C.J.; Ferreira, M.R.; dos Santos, S.A.A.; Justulin Junior, L.A.; del Valle Sosa, L.; Zambuzzi, W.F. Vascular smooth muscle cells exhibit elevated hypoxia-inducible Factor-1α expression in human blood vessel organoids, influencing osteogenic performance. Exp. Cell Res. 2024, 440, 114136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, J.; Sporkova, A.; Hecker, M.; Korff, T. Tracing G-Protein-Mediated Contraction and Relaxation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Spheroids. Cells 2023, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, K.; Wang, C.; Krajnik, A.; Yu, Y.; Choi, M.; Lin, B.; Jang, J.; Heo, S.-J.; Kolega, J.; Lee, K.; et al. A machine learning pipeline revealing heterogeneous responses to drug perturbations on vascular smooth muscle cell spheroid morphology and formation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegemann, J.P.; Hong, H.; Nerem, R.M. Mechanical, biochemical, and extracellular matrix effects on vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 2321–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyton, S.R.; Kim, P.D.; Ghajar, C.M.; Seliktar, D.; Putnam, A.J. The effects of matrix stiffness and RhoA on the phenotypic plasticity of smooth muscle cells in a 3-D biosynthetic hydrogel system. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 2597–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Z.; Peng, Q.; Larsen, T.; Gurevich, L.; de Claville Christiansen, J.; Zachar, V.; Pennisi, C.P. Tailoring Hydrogel Composition and Stiffness to Control Smooth Muscle Cell Differentiation in Bioprinted Constructs. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2023, 20, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ying, G.; Hu, C.; Du, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Yue, H.; Yetisen, A.K.; Wang, G.; Shen, Y.; et al. Engineering in vitro vascular microsystems. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2025, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engeland, N.C.A.; Pollet, A.; den Toonder, J.M.J.; Bouten, C.V.C.; Stassen, O.; Sahlgren, C.M. A biomimetic microfluidic model to study signalling between endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells under hemodynamic conditions. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, H.; Olivier, T.; Trietsch, S.J.; Vulto, P.; Burton, T.P.; van den Broek, L.J. Microfluidic artery-on-a-chip model with unidirectional gravity-driven flow for high-throughput applications. Lab A Chip 2025, 25, 2376–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Li, J.; Ming, Y.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, N.; Abudupataer, M.; Zhu, S.; Sun, X.; et al. A hiPSC-derived lineage-specific vascular smooth muscle cell-on-a-chip identifies aortic heterogeneity across segments. Lab A Chip 2023, 23, 1835–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daoud, F.; Arévalo Martinez, M.; Holmberg, J.; Alajbegovic, A.; Ali, N.; Rippe, C.; Swärd, K.; Albinsson, S. YAP and TAZ in Vascular Smooth Muscle Confer Protection Against Hypertensive Vasculopathy. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearing, B.V.; Jing, L.; Barcellona, M.N.; Witte, S.E.; Buchowski, J.M.; Zebala, L.P.; Kelly, M.P.; Luhmann, S.; Gupta, M.C.; Pathak, A.; et al. Mechanosensitive transcriptional coactivators MRTF-A and YAP/TAZ regulate nucleus pulposus cell phenotype through cell shape. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 14022–14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakar, R.G.; Cheng, Q.; Patel, S.; Chu, J.; Nasir, M.; Liepmann, D.; Komvopoulos, K.; Li, S. Cell-shape regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation. Biophys. J. 2009, 96, 3423–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Song, S.; Lee, J.; Yoon, J.; Park, J.; Choi, S.; Park, J.-K.; Choi, K.; Choi, C. Phenotypic Modulation of Primary Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Short-Term Culture on Micropatterned Substrate. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaterji, S.; Kim, P.; Choe, S.H.; Tsui, J.H.; Lam, C.H.; Ho, D.S.; Baker, A.B.; Kim, D.-H. Synergistic Effects of Matrix Nanotopography and Stiffness on Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Function. Tissue Eng. Part A 2014, 20, 2115–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kona, S.; Chellamuthu, P.; Xu, H.; Hills, S.R.; Nguyen, K.T. Effects of cyclic strain and growth factors on vascular smooth muscle cell responses. Open Biomed. Eng. J. 2009, 3, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walters, B.; Turner, P.A.; Rolauffs, B.; Hart, M.L.; Stegemann, J.P. Controlled Growth Factor Delivery and Cyclic Stretch Induces a Smooth Muscle Cell-like Phenotype in Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.C.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Z.; Hsu, T.F.; Wang, Y.; Shih, Y.T.; Peng, H.H.; Wang, N.; Guan, Y.; et al. Shear stress induces synthetic-to-contractile phenotypic modulation in smooth muscle cells via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta activations by prostacyclin released by sheared endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, J.-J.; Chen, L.-J.; Chang, S.-F.; Lee, P.-L.; Lee, C.-I.; Tsai, M.-C.; Lee, D.-Y.; Hsieh, H.-P.; Usami, S.; Chien, S. Shear Stress Inhibits Smooth Muscle Cell–Induced Inflammatory Gene Expression in Endothelial Cells. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Sakamoto, N.; Tomita, N.; Meng, H.; Sato, M.; Ohta, M. Influence of shear stress on phenotype and MMP production of smooth muscle cells in a co-culture model. J. Biorheol. 2017, 31, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Miéville, A.; Grob, F.; Yamashita, T.; Mehl, J.; Hosseini, V.; Emmert, M.Y.; Falk, V.; Vogel, V. Endothelial-Smooth Muscle Cell Interactions in a Shear-Exposed Intimal Hyperplasia on-a-Dish Model to Evaluate Therapeutic Strategies. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2202317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.-D.; Ji, X.-Y.; Qazi, H.; Tarbell, J.M. Interstitial flow promotes vascular fibroblast, myofibroblast, and smooth muscle cell motility in 3-D collagen I via upregulation of MMP-1. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 297, H1225–H1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.; Warren, H.S.; Cuenca, A.G.; Mindrinos, M.N.; Baker, H.V.; Xu, W.; Richards, D.R.; McDonald-Smith, G.P.; Gao, H.; Hennessy, L.; et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 3507–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denayer, T.; Stöhr, T.; Van Roy, M. Animal models in translational medicine: Validation and prediction. New Horiz. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Hansson, G.K. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature 2011, 473, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, H. Omics Approaches Unveiling the Biology of Human Atherosclerotic Plaques. Am. J. Pathol. 2024, 194, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Schmidlin, T. Recent advances in cardiovascular disease research driven by metabolomics technologies in the context of systems biology. NPJ Metab. Health Dis. 2024, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walder, L.; Pallocca, G.; Bastos, L.F.; Beekhuijzen, M.; Busquet, F.; Constantino, H.; Corvaro, M.; Courtot, L.; Escher, B.; Fernandez, R.; et al. EU roadmap for phasing out animal testing for chemical safety assessments: Recommendations from a multi-stakeholder roundtable. Altex 2025, 42, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, J. NIH Funds “Tissue Chip” Models for Drug Screening. JAMA 2017, 318, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; de Haan, P.; Ronaldson-Bouchard, K.; Kim, G.-A.; Ko, J.; Rho, H.S.; Chen, Z.; Habibovic, P.; Jeon, N.L.; Takayama, S.; et al. A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]