Interplay Between Glutamine Metabolism and Other Cellular Pathways: A Promising Hub in the Treatment of HNSCC

Highlights

- HNSCC tumors are highly dependent on glutamine (Gln) metabolism, with GLS1 as a key player in driving tumorigenesis.

- Targeting GLS1, ASCT2, and c-Myc in HNSCC disrupts Gln metabolism, with promising antitumor effects and potential immune benefits.

- Metabolic rewiring reduces the efficacy of single-agent therapies, highlighting the need for rational combination strategies.

- Tumor heterogeneity, model limitations, and lack of predictive biomarkers hinder clinical translation and require improved patient stratification.

Abstract

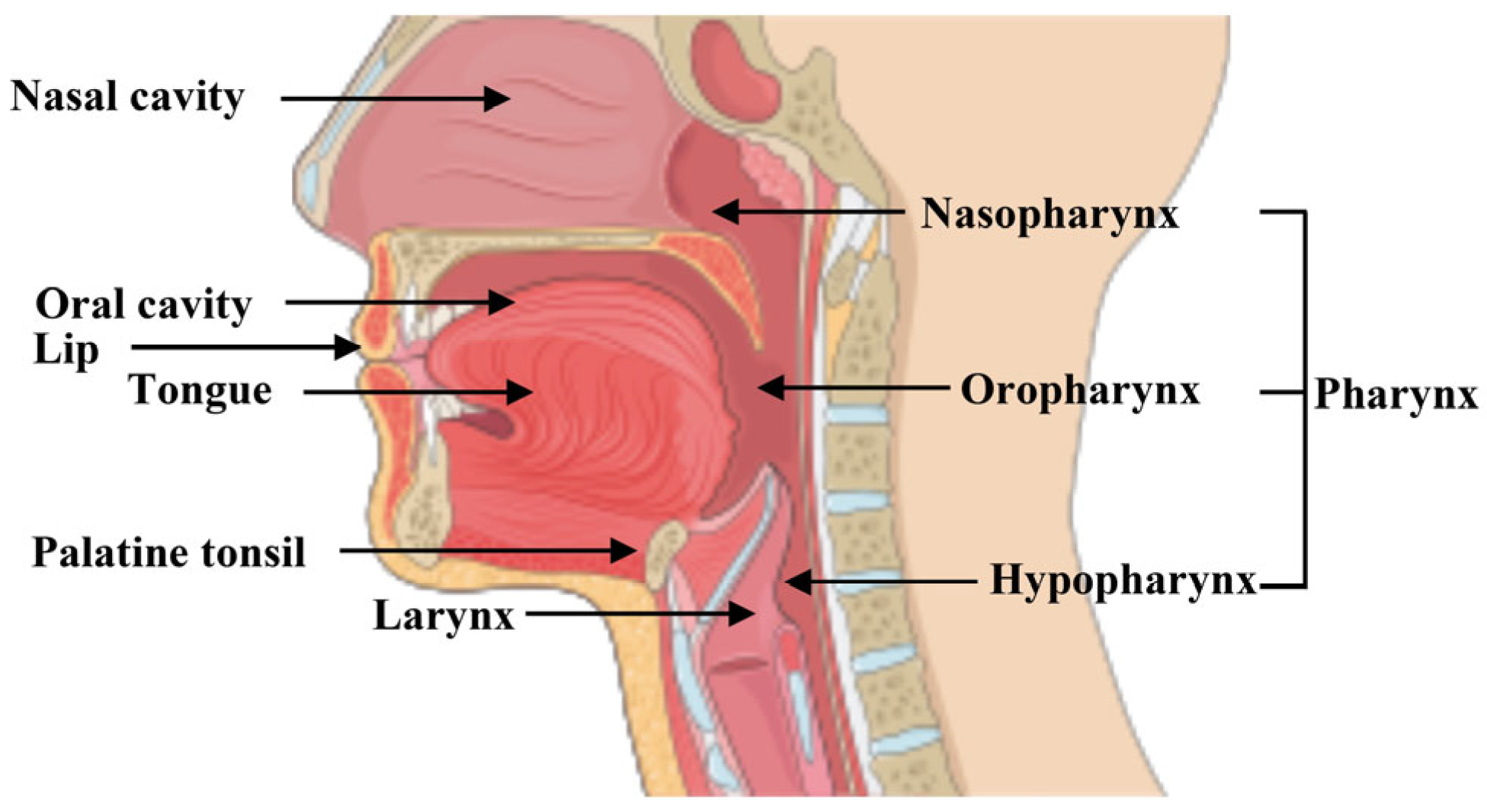

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Management of HNSCC: Treatment Toxicities and the Emerging Role of Glutamine Supplementation

3. Glutamine Signaling Pathway and Its Roles in Cellular Functions

4. Dysregulated Glutamine Metabolism in HNSCC

5. Glutamate Receptors and Their Roles in HNSCC

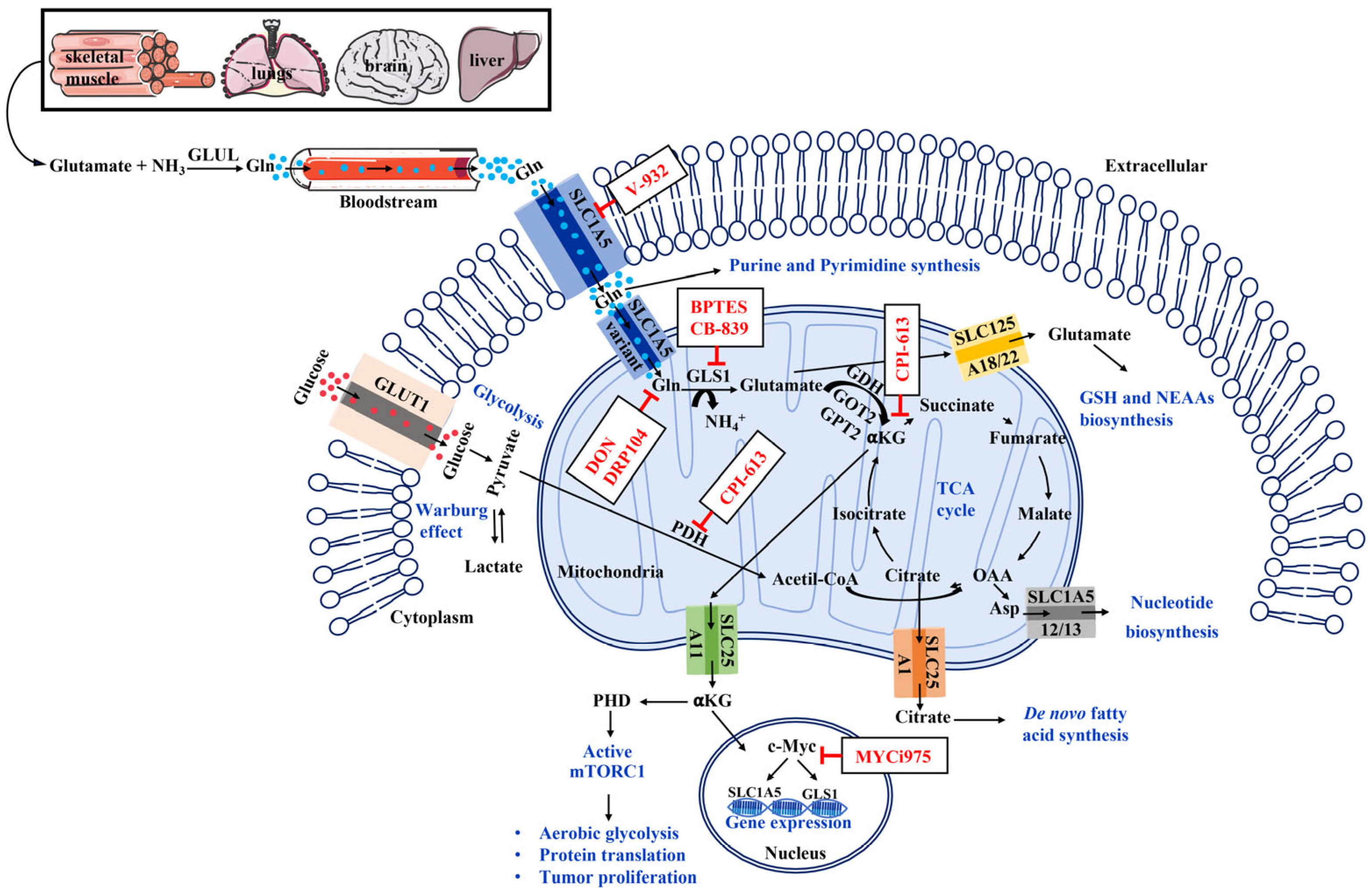

6. Glutamine Metabolism Checkpoints as a Potential Pharmacological Target in HNSCC Treatment

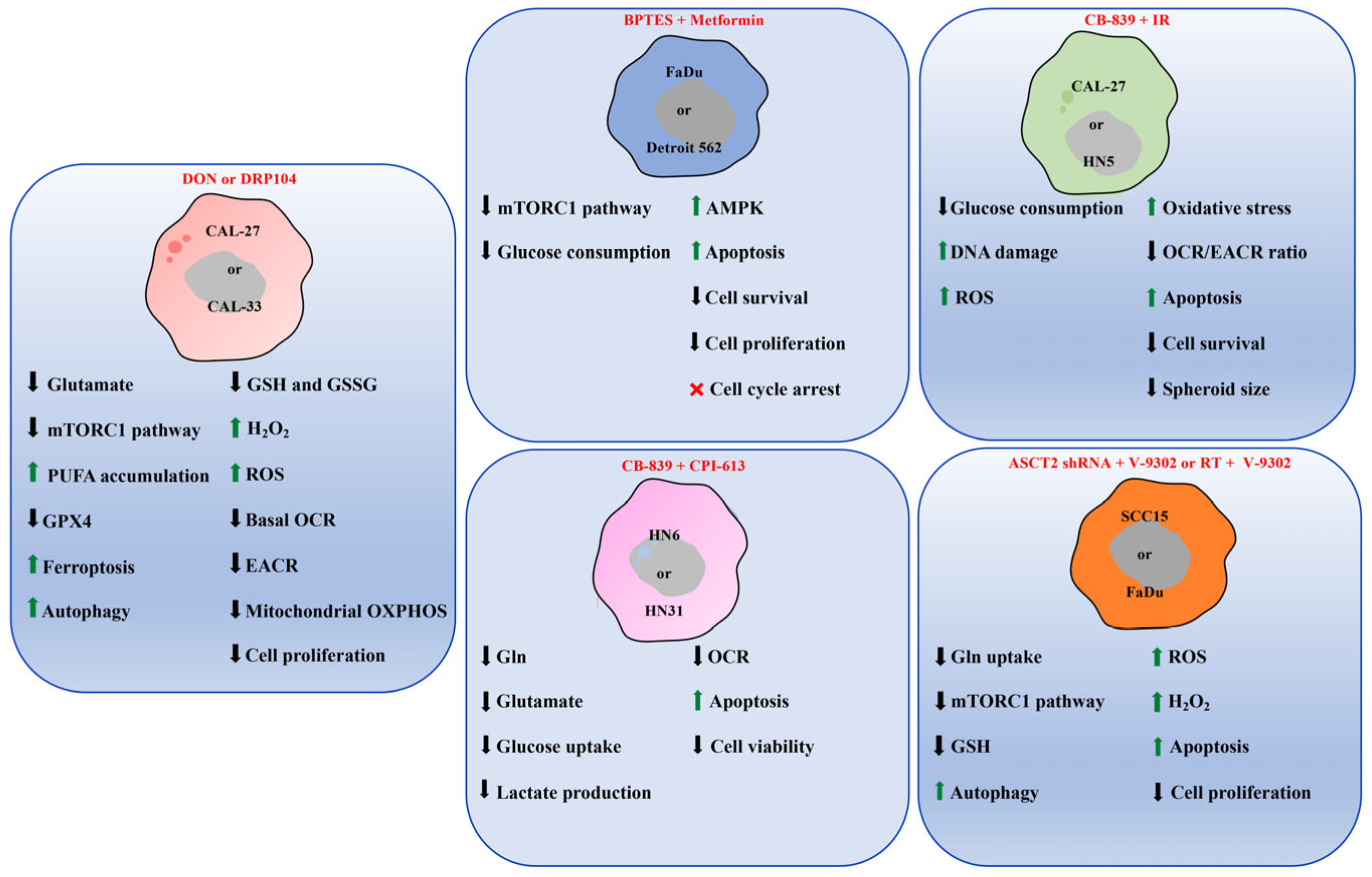

6.1. GLS1 Inhibition in HNSCC

6.2. GLS1 Enzyme Inhibition and Cancer Stemness in HNSCC

6.3. GLS1 Inhibition and Its Impact on Mitochondrial Energetics in HNSCC

6.4. ASCT2 Transporter Inhibition in HNSCC

6.5. ASCT2 Transporter Inhibition and Immune Modulation in HNSCC

7. Myc-Driven Regulation of Gln Metabolism in HNSCC

8. TP53-Mediated Regulation of Gln Metabolism in HNSCC

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| HNC | Head and neck cancer |

| Gln | Glutamine |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| CT | Chemotherapy |

| OPSCC | Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma |

| HPV | Human papilloma virus |

| GLS | Glutaminase |

| mGluR | Metabotropic glutamate receptors |

| iGluR | Ionotropic glutamate receptors |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| OM | Oral mucositis |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| NEAA | Non essential amino acid |

| ASCT2 | Cysteine-preferring transporter 2 |

| SLC1A5 | Solute-linked carrier family A1 member 5 |

| GLUL | Gln synthetase |

| GDH | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| α-KG | α-ketoglutarate |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| OAA | Oxaloacetate |

| c-Myc | Myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| IHC | Immunohistochemical |

| TMA | Tissue microarray |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| AMPA | [α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| KA | Kainite |

| EMT | epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| DON | 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine |

| DRP-104 | Sirpiglenastat |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| GPX4 | Selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase |

| GSSG | GSH oxidized form |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radicals |

| FSP1 | Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 |

| IREB2 | Iron-responsive element |

| BPTES | bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl) ethyl sulfide |

| CB-839 | Telaglenastat |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| ALDH | Aldehyde dehydrogenase |

| OCR | Oxygen consumption rate |

| ECAR | Extracellular acidification rate |

| CPI-613 | Alpha-lipoic acid analog |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| α-KGDH | alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase |

| SIRPα | Signal regulatory protein alpha |

| TSP1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| UTR | 3′-untranslated region |

| MYCi975 | Myc inhibitor 975 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 ligand |

| TP53 | Tumor suppressor gene p53 |

| WT | wild-type |

| GLUT1–GLUT4 | Glucose transporters |

References

- Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leemans, C.R.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Brakenhoff, R.H. The Molecular Landscape of Head and Neck Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda-Galvis, M.; Loveless, R.; Kowalski, L.P.; Teng, Y. Impacts of Environmental Factors on Head and Neck Cancer Pathogenesis and Progression. Cells 2021, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, L.; Chiocca, S.; Duca, D.; Tagliabue, M.; Simoens, C.; Gheit, T.; Arbyn, M.; Tommasino, M. Hpv and Head and Neck Cancers: Towards Early Diagnosis and Prevention. Tumour Virus Res. 2022, 14, 200245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, R.; Caprioli, S.; Lovino Camerino, P.; Sacco, G.; Ruelle, T.; Filippini, D.M.; Pamparino, S.; Vecchio, S.; Marchi, F.; Del Mastro, L.; et al. Clinical Evidence of Methods and Timing of Proper Follow-up for Head and Neck Cancers. Onco 2024, 4, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X.; Huang, S.; Duan, W. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: An Assessment Based on the Agree Ii, Agree-Rex Tools and the Right Checklist. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1442657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Y.; Seo, W.; Zhang, R.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, L.; Paul, B.; Yan, W.; Saxena, D.; et al. Targeting Cellular Metabolism to Reduce Head and Neck Cancer Growth. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, T.; Terazawa, K.; Shibata, H.; Inoue, N.; Ogawa, T. Metabolic Profiling Analysis of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarajan, P.; Rajendiran, T.M.; Kinchen, J.; Bermúdez, M.; Danciu, T.; Kapila, Y.L. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Metabolism Draws on Glutaminolysis, and Stemness Is Specifically Regulated by Glutaminolysis Via Aldehyde Dehydrogenase. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, H.A.; Elsalem, L.; Salem, A.; Tailor, A.; Hunter, K.; Afarinkia, K. The Expression of Glutaminases and Their Association with Clinicopathological Parameters in the Head and Neck Cancers. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2022, 22, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: Globocan Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, T.; Wasa, M.; Inohara, H.; Ito, T. L-Glutamine and Survival of Patients with Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Chemoradiotherapy. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Qie, S.; Sang, N. Carbon Source Metabolism and Its Regulation in Cancer Cells. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2012, 22, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise, M.; Pochini, L.; Console, L.; Losso, M.A.; Indiveri, C. The Human Slc1a5 (Asct2) Amino Acid Transporter: From Function to Structure and Role in Cell Biology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Talmon, G.; Wang, J. Glutamate in Cancers: From Metabolism to Signaling. J. Biomed. Res. 2020, 34, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geldermalsen, M.; Wang, Q.; Nagarajah, R.; Marshall, A.D.; Thoeng, A.; Gao, D.; Ritchie, W.; Feng, Y.; Bailey, C.G.; Deng, N.; et al. Asct2/Slc1a5 Controls Glutamine Uptake and Tumour Growth in Triple-Negative Basal-Like Breast Cancer. Oncogene 2016, 35, 3201–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Park, S.Y.; Hong, S.P.; Pai, H.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, S.G. The Expression of Nmda Receptor 1 Is Associated with Clinicopathological Parameters and Prognosis in the Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2004, 33, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigi-Ladiz, M.A.; Kordi-Tamandani, D.M.; Torkamanzehi, A. Analysis of Hypermethylation and Expression Profiles of Apc and Atm Genes in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Epigenetics 2011, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotti, A.; Bellm, L.A.; Epstein, J.B.; Frame, D.; Fuchs, H.J.; Gwede, C.K.; Komaroff, E.; Nalysnyk, L.; Zilberberg, M.D. Mucositis Incidence, Severity and Associated Outcomes in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Receiving Radiotherapy with or without Chemotherapy: A Systematic Literature Review. Radiother. Oncol. 2003, 66, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elting, L.S.; Cooksley, C.D.; Chambers, M.S.; Garden, A.S. Risk, Outcomes, and Costs of Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis among Patients with Head-and-Neck Malignancies. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 68, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, H.M.; Alsini, A.Y.; Alsubaie, K.M.; Abu-Zaid, A.; Alzahrani, F.R.; Sayed, S.; Pathak, A.K.; Alqahtani, K.H. Glutamine for Prevention and Alleviation of Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3199–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, L.; Panda, N.; Dash, M.K.; Mohanty, S.; Samantaray, S. Management of Chemoradiation-Induced Mucositis in Head and Neck Cancers with Oral Glutamine. J. Glob. Oncol. 2016, 2, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, P.M.; Biswas, G.; Dhamne, N.A.; Deshmukh, C.D.; Limaye, S.; Singh, A.; Malhotra, H.; Maniar, V.P.; Kapur, B.N.; Sripada, P.; et al. Practical Consensus Guidelines on the Use of Cetuximab in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Hnscc). South Asian J. Cancer 2025, 14, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G., Jr.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiwert, T.Y.; Burtness, B.; Mehra, R.; Weiss, J.; Berger, R.; Eder, J.P.; Heath, K.; McClanahan, T.; Lunceford, J.; Gause, C.; et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (Keynote-012): An Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 1b Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtness, B.; Harrington, K.J.; Greil, R.; Soulières, D.; Tahara, M.; de Castro, G., Jr.; Psyrri, A.; Basté, N.; Neupane, P.; Bratland, Å.; et al. Pembrolizumab Alone or with Chemotherapy Versus Cetuximab with Chemotherapy for Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (Keynote-048): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. Lancet 2019, 394, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tie, Y.; Alu, A.; Ma, X.; Shi, H. Targeted Therapy for Head and Neck Cancer: Signaling Pathways and Clinical Studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermorken, J.B.; Mesia, R.; Rivera, F.; Remenar, E.; Kawecki, A.; Rottey, S.; Erfan, J.; Zabolotnyy, D.; Kienzer, H.R.; Cupissol, D.; et al. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Plus Cetuximab in Head and Neck Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Radioimmunotherapy in Hpv-Associated Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, F.; Longo, F.; Caponigro, F.; Sandomenico, F.; Guida, A.; Della Vittoria Scarpati, G.; Ottaiano, A.; Muto, P.; Ionna, F. Management of Hpv-Related Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: Pitfalls and Caveat. Cancers 2020, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunhabdulla, H.; Manas, R.; Shettihalli, A.K.; Reddy, C.R.M.; Mustak, M.S.; Jetti, R.; Abdulla, R.; Sirigiri, D.R.; Ramdan, D.; Ammarullah, M.I. Identifying Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets by Multiomic Analysis for Hnscc: Precision Medicine and Healthcare Management. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 12602–12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; González-Maroto, C.; Tavassoli, M. Crosstalk between Cafs and Tumour Cells in Head and Neck Cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allevato, M.M.; Trinh, S.; Koshizuka, K.; Nachmanson, D.; Nguyen, T.C.; Yokoyama, Y.; Wu, X.; Andres, A.; Wang, Z.; Watrous, J.; et al. A Genome-Wide Crispr Screen Reveals That Antagonism of Glutamine Metabolism Sensitizes Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma to Ferroptotic Cell Death. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basnayake, B.; Leo, P.; Rao, S.; Vasani, S.; Kenny, L.; Haass, N.K.; Punyadeera, C. Head and Neck Cancer Patient-Derived Tumouroid Cultures: Opportunities and Challenges. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tang, J.; Lu, Y.; Jia, J.; Luo, T.; Su, K.; Dai, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, O. Prognosis-Related Molecular Subtyping in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Based on Glycolytic/Cholesterogenic Gene Data. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.C.; Yu, Y.C.; Sung, Y.; Han, J.M. Glutamine Reliance in Cell Metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1496–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, H.M.; Harris, J.L.; Carl, S.M.; Lezi, E.; Lu, J.; Eva Selfridge, J.; Roy, N.; Hutfles, L.; Koppel, S.; Morris, J.; et al. Oxaloacetate Activates Brain Mitochondrial Biogenesis, Enhances the Insulin Pathway, Reduces Inflammation and Stimulates Neurogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 6528–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, L.; Wang, F.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, X.; Loveless, R.; Xie, J.; Shay, C.; Qiu, P.; Ke, Y.; Saba, N.F.; et al. Blockade of Glutamine-Dependent Cell Survival Augments Antitumor Efficacy of Cpi-613 in Head and Neck Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, V.; Singh, A.; Bhatt, M.; Tonk, R.K.; Azizov, S.; Raza, A.S.; Sengupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Garg, M. Multifaceted Role of Mtor (Mammalian Target of Rapamycin) Signaling Pathway in Human Health and Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cui, L.; Lu, S.; Xu, S. Amino Acid Metabolism in Tumor Biology and Therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Baba, S.K.; Khan, I.R.; Khan, M.S.; Husain, F.M.; Ahmad, S.; Haris, M.; Singh, M.; Akil, A.S.A.; Macha, M.A.; et al. Glutamine Metabolism: Molecular Regulation, Biological Functions, and Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, I.; Carrillo-Bosch, L.; Seoane, J. Targeting the Warburg Effect in Cancer: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, N. Altered Metabolism in Cancer: Insights into Energy Pathways and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBerardinis, R.J.; Mancuso, A.; Daikhin, E.; Nissim, I.; Yudkoff, M.; Wehrli, S.; Thompson, C.B. Beyond Aerobic Glycolysis: Transformed Cells Can Engage in Glutamine Metabolism That Exceeds the Requirement for Protein and Nucleotide Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19345–19350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, S.; Yao, Y.; Xu, B.; Niu, Z.; Liao, F.; Wu, J.; Song, Q.; Li, M.; Liu, Z. Turbulence of Glutamine Metabolism in Pan-Cancer Prognosis and Immune Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1064127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wicker, C.A.; Hunt, B.G.; Krishnan, S.; Aziz, K.; Parajuli, S.; Palackdharry, S.; Elaban, W.R.; Wise-Draper, T.M.; Mills, G.B.; Waltz, S.E.; et al. Glutaminase Inhibition with Telaglenastat (Cb-839) Improves Treatment Response in Combination with Ionizing Radiation in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Models. Cancer Lett. 2021, 502, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qin, Z.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Peng, X. Therapeutic Targeting of MYC in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2130583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, F.; Lang, L.; Yang, F.; Fu, Z.; Martinez, J.; Cho, A.; Saba, N.F.; Teng, Y. Therapeutic Targeting of the Gls1-C-Myc Positive Feedback Loop Suppresses Glutaminolysis and Inhibits Progression of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3223–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, R.; Shuai, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jin, R.; Wang, X.; Luo, J. Asct2 (Slc1a5)-Dependent Glutamine Uptake Is Involved in the Progression of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Wu, L.; Zhang, B.X.; Yang, Q.C.; Liu, Y.T.; Li, H.; Mao, L.; Xiong, D.; Yu, H.J.; Sun, Z.J. Glutamine Inhibition Combined with Cd47 Blockade Enhances Radiotherapy-Induced Ferroptosis in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2024, 588, 216727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.-X.; Liu, Y.-J.; Yu, J.; Wang, R.; Chen, R.-Y.; Shi, J.-J.; Yang, G.-J.; Chen, J. Recent Insights into the Roles and Therapeutic Potentials of Gls1 in Inflammatory Diseases. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, M.; Kaira, K.; Ohshima, Y.; Ishioka, N.S.; Shino, M.; Sakakura, K.; Takayasu, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Tominaga, H.; Oriuchi, N.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Amino-Acid Transporter Expression (Lat1, Asct2, and Xct) in Surgically Resected Tongue Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2506–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, K.; Eddin, M.N.; Fateeva, A.; Pompili, S.V.B.; Shah, R.; Doshi, S.; Chen, S. Implications of a Neuronal Receptor Family, Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors, in Cancer Development and Progression. Cells 2022, 11, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koda, S.; Hu, J.; Ju, X.; Sun, G.; Shao, S.; Tang, R.X.; Zheng, K.Y.; Yan, J. The Role of Glutamate Receptors in the Regulation of the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1123841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, S.; Yang, D.; Li, K.; Li, D.; Zeng, X. Calcium Channels as Therapeutic Targets in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Current Evidence and Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1516357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Roy, N.K.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Banik, K.; Khwairakpam, A.D.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Sukumar, P. Orai-1 and Orai-2 Regulate Oral Cancer Cell Migration and Colonisation by Suppressing Akt/Mtor/Nf-Κb Signalling. Life Sci. 2020, 261, 118372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, S.A.; Han, I.H.; Yoo, B.C.; Lee, S.H.; Park, J.Y.; Cha, I.H.; Kim, J.; Choi, S.W. Clinical Significance of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2007, 17, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Koizumi, K.; Suzuki, M.; Kanayama, D.; Watanabe, Y.; Gouda, H.; Mori, H.; Mizuguchi, M.; Obita, T.; Nabeshima, Y.; et al. Design, Synthesis, Structure–Activity Relationship Studies, and Evaluation of Novel Gls1 Inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 87, 129266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Jain, A.D.; Truica, M.I.; Izquierdo-Ferrer, J.; Anker, J.F.; Lysy, B.; Sagar, V.; Luan, Y.; Chalmers, Z.R.; Unno, K.; et al. Small-Molecule MYC Inhibitors Suppress Tumor Growth and Enhance Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 483–497.e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, N.; Chen, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, S. Metformin as an Immunomodulatory Agent in Enhancing Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.C.; Huang, C.S.; Hsieh, M.S.; Huang, C.M.; Setiawan, S.A.; Yeh, C.T.; Kuo, K.T.; Liu, S.C. Targeting of Fsp1 Regulates Iron Homeostasis in Drug-Tolerant Persister Head and Neck Cancer Cells Via Lipid-Metabolism-Driven Ferroptosis. Aging 2024, 16, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Woods, C.M.; Dharmawardana, N.; Michael, M.Z.; Ooi, E.H. The Mechanisms of Action of Metformin on Head and Neck Cancer in the Pre-Clinical Setting: A Scoping Review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1358854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Stalnecker, C.; Zhang, C.; McDermott, L.A.; Iyer, P.; O’Neill, J.; Reimer, S.; Cerione, R.A.; Katt, W.P. Characterization of the Interactions of Potent Allosteric Inhibitors with Glutaminase C, a Key Enzyme in Cancer Cell Glutamine Metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, M.I.; Demo, S.D.; Dennison, J.B.; Chen, L.; Chernov-Rogan, T.; Goyal, B.; Janes, J.R.; Laidig, G.J.; Lewis, E.R.; Li, J.; et al. Antitumor Activity of the Glutaminase Inhibitor Cb-839 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoulidis, F.; Neal, J.W.; Akerley, W.L.; Paik, P.K.; Papagiannakopoulos, T.; Reckamp, K.L.; Riess, J.W.; Jenkins, Y.; Holland, S.; Parlati, F. A Phase II Randomized Study of Telaglenastat, a Glutaminase (GLS) Inhibitor, Versus Placebo, in Combination with Pembrolizumab (Pembro) and Chemotherapy as First-Line Treatment for KEAP1/NRF2-Mutated Non-Squamous Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (mNSCLC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, TPS9627. [Google Scholar]

- Biancur, D.E.; Paulo, J.A.; Małachowska, B.; Quiles Del Rey, M.; Sousa, C.M.; Wang, X.; Sohn, A.S.; Chu, G.C.; Gygi, S.P.; Harper, J.W.; et al. Compensatory Metabolic Networks in Pancreatic Cancers Upon Perturbation of Glutamine Metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Bhutia, Y.D.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Ganapathy, V. Metabolic Signature of Warburg Effect in Cancer: An Effective and Obligatory Interplay between Nutrient Transporters and Catabolic/Anabolic Pathways to Promote Tumor Growth. Cancers 2024, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, G.T.; Deng, W.W.; Mao, L.; Yang, L.L.; Ma, S.R.; Bu, L.L.; Kulkarni, A.B.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, L.; et al. Anti-Cd47 Treatment Enhances Anti-Tumor T-Cell Immunity and Improves Immunosuppressive Environment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1397248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambay, V.; Raymond, V.A.; Bilodeau, M. MYC Rules: Leading Glutamine Metabolism toward a Distinct Cancer Cell Phenotype. Cancers 2021, 13, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; An, L.; Yang, X.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Identification and Validation of the Role of C-Myc in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 820587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.Q.; Yu, F.Q.; Chen, C. C-Myc Regulates Pd-L1 Expression in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, D.; Song, N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W.; Yu, Y.; Han, C. Mutant p53 in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Molecular Mechanism of Gain-of-Function and Targeting Therapy (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2023, 50, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponio, V.C.A.; Troiano, G.; Adipietro, I.; Zhurakivska, K.; Arena, C.; Mangieri, D.; Mascitti, M.; Cirillo, N.; Lo Muzio, L. Computational Analysis of TP53 Mutational Landscape Unveils Key Prognostic Signatures and Distinct Pathobiological Pathways in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 123, 1302–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponio, V.C.A.; Zhurakivska, K.; Mascitti, M.; Togni, L.; Spirito, F.; Cirillo, N.; Lo Muzio, L.; Troiano, G. High-Risk TP53 Mutations Predict Poor Primary Treatment Response of Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bakker, T.; Journe, F.; Descamps, G.; Saussez, S.; Dragan, T.; Ghanem, G.; Krayem, M.; Van Gestel, D. Restoring p53 Function in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma to Improve Treatments. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 799993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencel-Augusto, J.; Li, H.; Woerner, L.C.; Tian, N.; Borah, A.A.; Myers, J.N.; Ha, P.; Johnson, D.E.; Grandis, J.R. Human Papilloma Virus Does Not Fully Inactivate p53 Cellular Activity in HNSCC. Head Neck 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mireștean, C.C.; Iancu, R.I.; Iancu, D.P.T. p53 Modulates Radiosensitivity in Head and Neck Cancers—From Classic to Future Horizons. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Tanaka, T.; Poyurovsky, M.V.; Nagano, H.; Mayama, T.; Ohkubo, S.; Lokshin, M.; Hosokawa, H.; Nakayama, T.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Phosphate-Activated Glutaminase (GLS2), a p53-Inducible Regulator of Glutamine Metabolism and Reactive Oxygen Species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7461–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, P.; Garrido, M.; Oliver, J.; Perez-Ruiz, E.; Barragan, I.; Rueda-Dominguez, A. Preclinical Models in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, R.; Takigawa, H.; Yuge, R.; Shimizu, D.; Ariyoshi, M.; Otani, R.; Tsuboi, A.; Tanaka, H.; Yamashita, K.; Hiyama, Y.; et al. Analysis of Anti-Tumor Effect and Mechanism of Gls1 Inhibitor Cb-839 in Colorectal Cancer Using a Stroma-Abundant Tumor Model. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2024, 137, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Increase;

Increase;  Decrease;

Decrease;  Arrest. Figure created using SMART—Servier Medical Art https://smart.servier.com/SMART (accessed on 1 June 2025).

Arrest. Figure created using SMART—Servier Medical Art https://smart.servier.com/SMART (accessed on 1 June 2025).

Increase;

Increase;  Decrease;

Decrease;  Arrest. Figure created using SMART—Servier Medical Art https://smart.servier.com/SMART (accessed on 1 June 2025).

Arrest. Figure created using SMART—Servier Medical Art https://smart.servier.com/SMART (accessed on 1 June 2025).

| Cell Line | Primary Site of Origin | Gender | HPV Status | GLS1 Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAL-27 | Tongue | Male | Negative | High | [33,47] |

| CAL-33 | Tongue | Male | Not shown | [33] | |

| Detroit 562 | Pharynx | Female | High | [7] | |

| FaDu | Hypopharynx | Male | High | [7,46] | |

| HN5 | Tongue | Male | High | [46] | |

| HN6 | Tongue | Male | High | [38,48] | |

| HN12 | Lymph node metastasis of the tongue | Male | High | [38,48] | |

| HN31 | Lymph node metastasis of the tongue | Male | High | [38,48] | |

| HSC-3 | Lymph node metastasis of the tongue | Male | High | [9] | |

| OSCC-3 | Tongue | Unknown | High | [9] | |

| SCC15 | Tongue | Male | Not shown | [49] | |

| UM-SCC-14A | Floor of mouth | Female | High | [9] | |

| UM-SCC-17B | Metastatic laryngeal cancer | Female | High | [9] | |

| UDSCC2 | Hypopharynx | Male | Positive (HPV-16) | High | [33] |

| UM-SCC47 | Lateral tongue | Male | High | [33] | |

| SCC7 | HNSCC model established in C3H/HeJ mice | Negative | Not shown | [50] | |

| 4MOSC1/MSCC1 | HNSCC model induced in C57BL/6 mice, by carcinogen 4-nitroquinoline (4NQO) | [47,50] |

| Marker | Gene Expression (TCGA Datasets, RT-qPCR) | Protein Expression (IHC) |

|---|---|---|

| GLS1 | Upregulated in HNSCC primary and metastatic tumor tissues [7,8,49]. | Overexpressed in tumor tissues compared with adjacent normal mucosa. Significantly and inversely associated with OS [9,10,49]. |

| GLS2 | Downregulated in HNSCC tissues [10,49]. | Overexpressed and correlated negatively with tumor grade [10]. Its expression in tumor tissues showed a trend toward better OS [49]. |

| SLC1A5 (ASCT2) | Upregulated and significantly associated with sex and HNSCC subtype, depending on anatomical origin [49]. | Overexpressed and higher in HNSCC post-RT; higher in Cetuximab non-responder patients. Elevated expression in HPV (+) cases, correlated with poor OS. Significantly associated with advanced T stage, differentiation grade, sex, and lymph node metastasis [49,50,52]. |

| Metabolite | Metabolomic Analysis on tissues, saliva, plasma, and serum | |

| Glutamate | Significantly elevated metabolite levels in primary and metastatic HNSCC samples, correlated with advanced clinicopathological features [8,9]. | |

| Glutamine | Lower levels of Gln in metastatic HNSCC tissues compared to primary tumors, and associated with advanced stages of HNSCC. Reduced Gln concentrations also in saliva, plasma, and serum of HNSCC patients [8,9,50]. | |

| Therapeutic Agent | Characteristics | Mechanism of Action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DON | Glutamine antagonist | Antimetabolites bind competitively to the active site of GLS1, preventing Gln from binding and thereby inhibiting GLS1 enzymatic activity. | [58] |

| DRP104 | [58] | ||

| BPTES | GLS1 inhibitor | Selective inhibition of GLS1 enzyme blocks Gln conversion to glutamate. | [58] |

| CB-839 | [46] | ||

| CPI-613 | PDH/⍺KGDH inhibitor | Alpha-lipoic acid analog inhibiting tumor mitochondrial metabolism by targeting two TCA cycle enzymes: pyruvate dehydrogenase and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, affecting cancer cell proliferation and survival. | [38] |

| V-9302 | ASCT2 inhibitor | Inhibits of ASCT2 transporter, blocking the Gln uptake and its metabolism. | [49] |

| MYCi975 | c-Myc inhibitor | Target the c-Myc oncogenic transcription factor. | [59] |

| Metformin | Antihyperglycemic drug | Inhibits mitochondrial Complex I of the electron transport chain, activates AMPK, and suppresses mTORC1 leading to reduced proliferation and altered tumor metabolism. | [60] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dell’Endice, T.S.; Posa, F.; Storlino, G.; Sanesi, L.; Lo Russo, L.; Mori, G. Interplay Between Glutamine Metabolism and Other Cellular Pathways: A Promising Hub in the Treatment of HNSCC. Cells 2025, 14, 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241962

Dell’Endice TS, Posa F, Storlino G, Sanesi L, Lo Russo L, Mori G. Interplay Between Glutamine Metabolism and Other Cellular Pathways: A Promising Hub in the Treatment of HNSCC. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241962

Chicago/Turabian StyleDell’Endice, Teresa Stefania, Francesca Posa, Giuseppina Storlino, Lorenzo Sanesi, Lucio Lo Russo, and Giorgio Mori. 2025. "Interplay Between Glutamine Metabolism and Other Cellular Pathways: A Promising Hub in the Treatment of HNSCC" Cells 14, no. 24: 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241962

APA StyleDell’Endice, T. S., Posa, F., Storlino, G., Sanesi, L., Lo Russo, L., & Mori, G. (2025). Interplay Between Glutamine Metabolism and Other Cellular Pathways: A Promising Hub in the Treatment of HNSCC. Cells, 14(24), 1962. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241962