Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives

Highlights

- Thermoregulatory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease (PD) arises from combined central and peripheral α-synuclein pathology, disrupting hypothalamic integration, sudomotor, vasomotor, and thermogenic pathways.

- Distinct alterations in sweating, heat and cold tolerance, and crisis syndromes such as parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia and hypothermia underscore the multisystem nature of PD’s autonomic impairment.

- Recognizing and managing thermoregulatory dysfunction can improve patient safety, reduce hospitalization risk, and enhance quality of life in PD.

- Future studies should investigate how PD affects brown adipose tissue (BAT) and shivering thermogenesis, offering potential targets for restoring heat balance and metabolic stability.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Normal Thermoregulatory Function

2.1. Thermosensitivity

- (1)

- Peripheral thermosensitive neurons, located in the somatic and visceral layers of the body, which provide thermal information to higher brain structures via second-order neurons.

- (2)

- Central thermosensitive neurons, located within central structures of the brain, which monitor and provide local thermal information.

2.2. Thermoeffectors

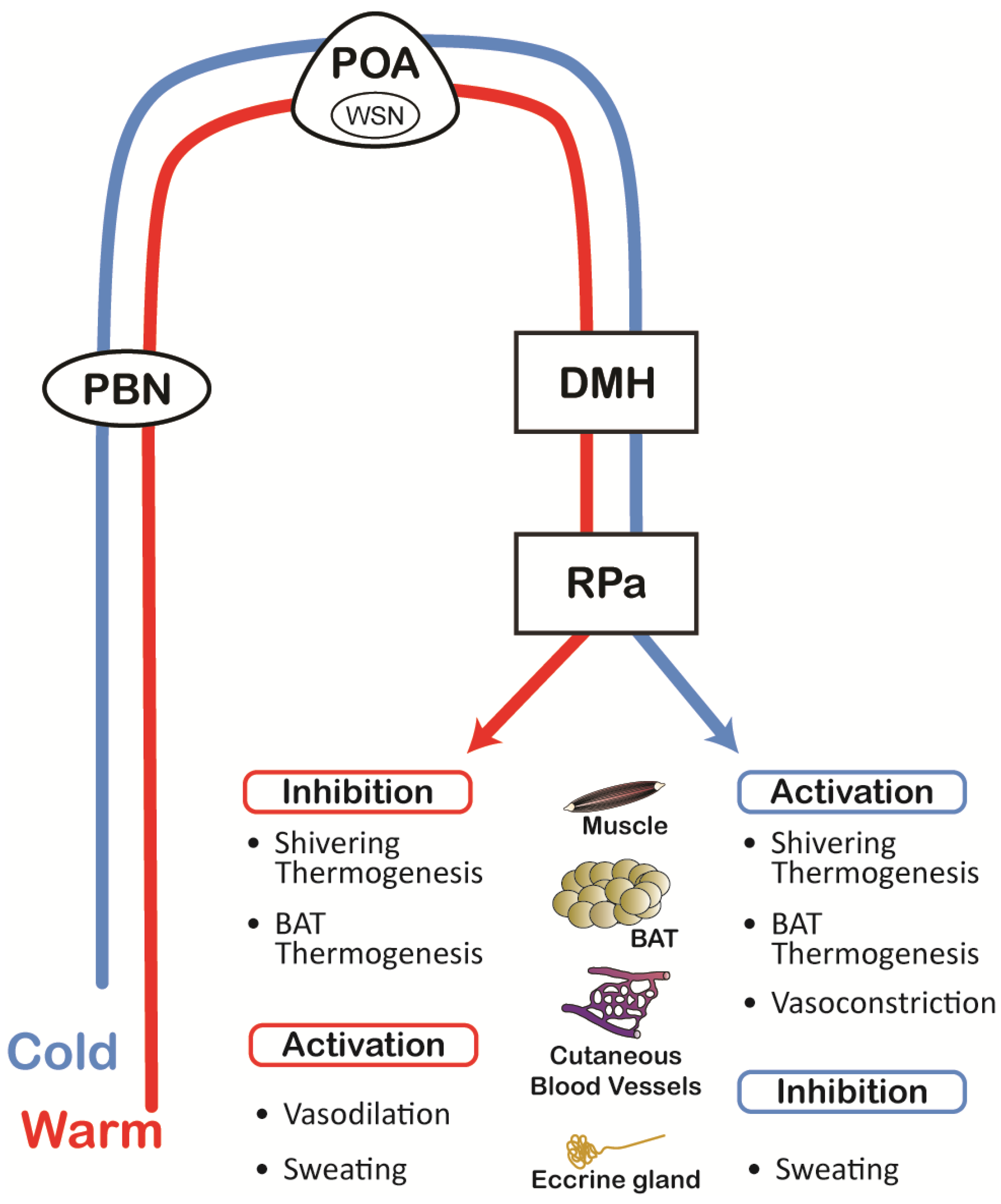

2.3. Thermoregulatory Network

2.4. Circadian, Sleep, and Aging Influences

2.5. Behavioral and Higher-Order Regulation

3. Thermoregulatory Pathophysiology in Parkinson’s Disease

4. Manifestations of Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease

4.1. Hyperhidrosis

4.2. Anhidrosis, Hypohidrosis, and Heat Intolerance

4.3. Hyperthermia and Parkinsonism Hyperpyrexia

4.4. Hypothermia

4.5. Medication-Related Thermoregulatory Effects

5. Diagnostics and Tests

5.1. Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test (QSART)

5.2. Thermoregulatory Sweat Test (TST)

5.3. Sympathetic Skin Response (SSR)

5.4. Electrochemical Skin Conductance (ESC; Sudoscan)

5.5. Laser Doppler Flowmetry (LDF) and Imaging (LDI) of the Vasomotor Axon Reflex

5.6. Sensitive Sweat Test and Spoon Test

5.7. Experienced Temperature Sensitivity and Regulation Survey (ETSRS)

5.8. Emerging and Research-Based Tests

6. Management of Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease

6.1. Hyperhidrosis

6.2. Hypothermia

6.3. Anhidrosis, Hypohidrosis, and Heat Intolerance

6.4. Hyperthermia and Parkinsonism–Hyperpyrexia Syndrome

6.5. Medication-Related Thermoregulatory Effects

7. Gaps and Areas for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parkinson, J. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy; Whittingham and Rowland, for Sherwood, Neely, and Jones: London, UK, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- Gowers, W.R. A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System; P. Blakiston, Son & Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1898; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Healy, D.G.; Schapira, A.H.; National Institute for Clinical, E. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S1), S119–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.D. Chapter 19—Central neural substrates involved in temperature discrimination, thermal pain, thermal comfort, and thermoregulatory behavior. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, S.F. Chapter 17—Efferent neural pathways for the control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and shivering. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky, A.A. Chapter 1—The thermoregulation system and how it works. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, S.F.; Madden, C.J.; Tupone, D. Central neural regulation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morrison, S.F.; Madden, C.J.; Tupone, D. Central control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2012, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Wamelen, D.J.; Leta, V.; Podlewska, A.M.; Wan, Y.M.; Krbot, K.; Jaakkola, E.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Rizos, A.; Parry, M.; Metta, V.; et al. Exploring hyperhidrosis and related thermoregulatory symptoms as a possible clinical identifier for the dysautonomic subtype of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kataoka, H.; Eura, N.; Kiriyama, T.; Uchihara, Y.; Sugie, K. Accidental hypothermia in Parkinson’s disease. Oxf. Med. Case Rep. 2018, 2018, omy089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brim, B.; Struhal, W. Chapter Ten—Thermoregulatory dysfunctions in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. In International Review of Movement Disorders; Falup-Pecurariu, C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas-Arroyave, N.; Caroff, S.N.; Citrome, L.; Crasta, J.; McIntyre, R.S.; Meyer, J.M.; Patel, A.; Smith, J.M.; Farahmand, K.; Manahan, R.; et al. An Evidence-Based Update on Anticholinergic Use for Drug-Induced Movement Disorders. CNS Drugs 2024, 38, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bongioanni, P.; Del Carratore, R.; Corbianco, S.; Diana, A.; Cavallini, G.; Masciandaro, S.M.; Dini, M.; Buizza, R. Climate change and neurodegenerative diseases. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolano, M.; Caporaso, G.; Manganelli, F.; Stancanelli, A.; Borreca, I.; Mozzillo, S.; Tozza, S.; Dubbioso, R.; Iodice, R.; Vitale, F.; et al. Phosphorylated alpha-Synuclein Deposits in Cutaneous Nerves of Early Parkinsonism. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 12, 2453–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, C.; Wang, N.; Rajan, S.; Kern, D.; Palma, J.A.; Kaufmann, H.; Freeman, R. Cutaneous alpha-Synuclein Signatures in Patients with Multiple System Atrophy and Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2023, 100, e1529–e1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Provitera, V.; Iodice, V.; Manganelli, F.; Mozzillo, S.; Caporaso, G.; Stancanelli, A.; Borreca, I.; Esposito, M.; Dubbioso, R.; Iodice, R.; et al. Postganglionic Sudomotor Assessment in Early Stage of Multiple System Atrophy and Parkinson Disease: A Morpho-functional Study. Neurology 2022, 98, e1282–e1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kimpinski, K.; Iodice, V.; Burton, D.D.; Camilleri, M.; Mullan, B.P.; Lipp, A.; Sandroni, P.; Gehrking, T.L.; Sletten, D.M.; Ahlskog, J.E.; et al. The role of autonomic testing in the differentiation of Parkinson’s disease from multiple system atrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 317, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McKemy, D.D. Chapter 3—Molecular basis of peripheral innocuous cold sensitivity. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S.; Caterina, M.J. Chapter 4—Molecular basis of peripheral innocuous warmth sensitivity. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jänig, W. Chapter 2—Peripheral thermoreceptors in innocuous temperature detection. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, S.; Musinszki, M. Thermosensitivity of TREK K2P channels is controlled by a PKA switch and depends on the microtubular network. Pflug. Arch. 2025, 477, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tabarean, I. Chapter 7—Central thermoreceptors. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shido, O.; Matsuzaki, K.; Katakura, M. Chapter 28—Neurogenesis in the thermoregulatory system. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 457–463. [Google Scholar]

- Ambroziak, W.; Nencini, S.; Pohle, J.; Zuza, K.; Pino, G.; Lundh, S.; Araujo-Sousa, C.; Goetz, L.I.L.; Schrenk-Siemens, K.; Manoj, G.; et al. Thermally induced neuronal plasticity in the hypothalamus mediates heat tolerance. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, J.M.; Kellogg, D.L. Chapter 11—Skin vasoconstriction as a heat conservation thermoeffector. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Francisco, M.A.; Minson, C.T. Chapter 12—Cutaneous active vasodilation as a heat loss thermoeffector. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- McAllen, R.M.; McKinley, M.J. Chapter 18—Efferent thermoregulatory pathways regulating cutaneous blood flow and sweating. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, K. Chapter 16—Afferent pathways for autonomic and shivering thermoeffectors. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Nedergaard, J.; Cannon, B. Chapter 9—Brown adipose tissue as a heat-producing thermoeffector. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, D.; Crandall, C.G. Chapter 13—Sweating as a heat loss thermoeffector. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Székely, M.; Garai, J. Chapter 23—Thermoregulation and age. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Tupone, D.; Madden, C.J.; Morrison, S.F. Autonomic regulation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in health and disease: Potential clinical applications for altering BAT thermogenesis. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morrison, S.F.; Nakamura, K. Central Mechanisms for Thermoregulation. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, S.F.; Cano, G.; Hernan, S.L.; Chiavetta, P.; Tupone, D. Inhibition of the hypothalamic ventromedial periventricular area activates a dynorphin pathway-dependent thermoregulatory inversion in rats. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 59–76.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, W.Z.; Xie, H.; Du, X.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Cai, S.; et al. A parabrachial-hypothalamic parallel circuit governs cold defense in mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dimicco, J.A.; Zaretsky, D.V. The dorsomedial hypothalamus: A new player in thermoregulation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2007, 292, R47–R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Li, X.; Cano, G.; Lazarus, M.; Saper, C.B. Parallel preoptic pathways for thermoregulation. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 11954–11964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Machado, N.L.S.; Abbott, S.B.G.; Resch, J.M.; Zhu, L.; Arrigoni, E.; Lowell, B.B.; Fuller, P.M.; Fontes, M.A.P.; Saper, C.B. A Glutamatergic Hypothalamomedullary Circuit Mediates Thermogenesis, but Not Heat Conservation, during Stress-Induced Hyperthermia. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2291–2301.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pinol, R.A.; Zahler, S.H.; Li, C.; Saha, A.; Tan, B.K.; Skop, V.; Gavrilova, O.; Xiao, C.; Krashes, M.J.; Reitman, M.L. Brs3 neurons in the mouse dorsomedial hypothalamus regulate body temperature, energy expenditure, and heart rate, but not food intake. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, Q.; Liu, C.; Chen, T.; Liu, Y.; Cao, R.; Ni, X.; Yang, W.Z.; Shen, Q.; Sun, H.; Shen, W.L. Cooling-activated dorsomedial hypothalamic BDNF neurons control cold defense in mice. J. Neurochem. 2022, 163, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Yu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Laque, A.; Schwartzenburg, C.; Morrison, C.D.; Derbenev, A.V.; Zsombok, A.; Munzberg, H. Leptin receptor neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus are key regulators of energy expenditure and body weight, but not food intake. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jeong, J.H.; Lee, D.K.; Blouet, C.; Ruiz, H.H.; Buettner, C.; Chua, S., Jr.; Schwartz, G.J.; Jo, Y.H. Cholinergic neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus regulate mouse brown adipose tissue metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Conceicao, E.P.S.; Morrison, S.F.; Cano, G.; Chiavetta, P.; Tupone, D. Median preoptic area neurons are required for the cooling and febrile activations of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis in rat. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tupone, D.; Madden, C.J.; Cano, G.; Morrison, S.F. An orexinergic projection from perifornical hypothalamus to raphe pallidus increases rat brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 15944–15955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cerri, M.; Zamboni, G.; Tupone, D.; Dentico, D.; Luppi, M.; Martelli, D.; Perez, E.; Amici, R. Cutaneous vasodilation elicited by disinhibition of the caudal portion of the rostral ventromedial medulla of the free-behaving rat. Neuroscience 2010, 165, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tupone, D.; Cano, G.; Morrison, S.F. Thermoregulatory Inversion—A novel thermoregulatory paradigm. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2017, 312, R779–R786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinn, L.; Schrag, A.; Viswanathan, R.; Bloem, B.R.; Lees, A.; Quinn, N. Sweating dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2003, 18, 1459–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leta, V.; van Wamelen, D.J.; Rukavina, K.; Jaakkola, E.; Sportelli, C.; Wan, Y.-M.; Podlewska, A.M.; Parry, M.; Metta, V.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Sweating and other thermoregulatory abnormalities in Parkinson’s disease: A review. Ann. Mov. Disord. 2019, 2, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, J.M.; Emborg, M.E. Autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson disease and animal models. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coon, E.A.; Low, P.A. Thermoregulation in Parkinson disease. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 157, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siepmann, T.; Arndt, M.; Sedghi, A.; Szatmari, S., Jr.; Horvath, T.; Takats, A.; Bereczki, D.; Moskopp, M.L.; Buchmann, S.; Skowronek, C.; et al. Two-Year observational study of autonomic skin function in patients with Parkinson’s disease compared to healthy individuals. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 1281–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymusiak, R. Chapter 20—Body temperature and sleep. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Blessing, W.W. Chapter 22—Thermoregulation and the ultradian basic rest–activity cycle. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Te Lindert, B.H.W.; Van Someren, E.J.W. Chapter 21—Skin temperature, sleep, and vigilance. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Romanovsky, A.A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 156, pp. 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, H. Sudomotor deficits in Parkinson’s disease with special reference to motor subtypes. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2023, 114, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, D.W. Neuropathology of Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2018, 46 (Suppl. S1), S30–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meigal, A.; Lupandin, Y. “Thermoregulation-dependent component” in pathophysiology of motor disorders in Parkinson’s disease? Pathophysiology 2005, 11, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, K.; Tsuchiya, M.; Ichinose, Y.; Koh, K.; Hata, T.; Yamashiro, N.; Kobayashi, F.; Nagasaka, T.; Takiyama, Y. Pre- and postganglionic vasomotor dysfunction causes distal limb coldness in multiple system atrophy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 380, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, B.; Lee, T.F. Further evidence for a physiological role for hypothalamic dopamine in thermoregulation in the rat. J. Physiol. 1980, 300, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giorelli, M.; Bagnoli, J.; Consiglio, L.; Difazio, P.; Zizza, D.; Zimatore, G.B. Change in Non-motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease and Essential Tremor Patients: A One-year Follow-up Study. Tremor. Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2014, 4, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ou, R.; Yang, J.; Cao, B.; Wei, Q.; Chen, K.; Chen, X.; Zhao, B.; Wu, Y.; Song, W.; Shang, H. Progression of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease among different age populations: A two-year follow-up study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 360, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubignat, M. Hyperhidrosis from diagnosis to management. Rev. Med. Interne 2021, 42, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, M. Sweating dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2006, 253 (Suppl. S7), VII42–VII47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schestatsky, P.; Valls-Sole, J.; Ehlers, J.A.; Rieder, C.R.; Gomes, I. Hyperhidrosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 1744–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obed, D.; Salim, M.; Bingoel, A.S.; Hofmann, T.R.; Vogt, P.M.; Krezdorn, N. Botulinum Toxin Versus Placebo: A Meta-Analysis of Treatment and Quality-of-life Outcomes for Hyperhidrosis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doft, M.A.; Hardy, K.L.; Ascherman, J.A. Treatment of hyperhidrosis with botulinum toxin. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2012, 32, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Zamora, A.; Smith, H.; Youn, Y.; Durphy, J.; Shin, D.S.; Pilitsis, J.G. Hyperhidrosis associated with subthalamic deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: Insights into central autonomic functional anatomy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 366, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerknes, S.; Skogseid, I.M.; Hauge, T.J.; Dietrichs, E.; Toft, M. Subthalamic deep brain stimulation improves sleep and excessive sweating in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trachani, E.; Constantoyannis, C.; Sirrou, V.; Kefalopoulou, Z.; Markaki, E.; Chroni, E. Effects of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation on sweating function in Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010, 112, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, A.P.; Pagnussat, A.S.; Lehn, A.; Moore, D.; Schweitzer, D.; Laakso, E.L.; Hennig, E.; Morris, M.E.; Kerr, G.; Stewart, I. Evidence of heat sensitivity in people with Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Reyes, J.V.M.; Lieber, J. Oxybutynin-Induced Hyperthermia in a Patient With Parkinson’s Disease. Cureus 2021, 13, e14701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Douglas, A.; Morris, J. It was not just a heatwave! Neuroleptic malignant-like syndrome in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 640–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, E.J.; Grosset, D.G.; Kennedy, P.G. The parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome. Neurocrit Care 2009, 10, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azar, J.; Jaber, Y.; Ayyad, M.; Abu Alia, W.; Owda, F.; Sharabati, H.; Zeid, H.; Khreshi, S.; AlBandak, M.; Sayyed Ahmad, D. Parkinsonism-Hyperpyrexia Syndrome: A Case Series and Literature Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e29646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grover, S.; Sathpathy, A.; Reddy, S.C.; Mehta, S.; Sharma, N. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Indian. J. Psychiatry 2018, 60, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ebadi, M.; Pfeiffer, R.F.; Murrin, L.C. Pathogenesis and treatment of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Gen. Pharmacol. 1990, 21, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotz, M.; Thummler, D.; Schurch, M.; Renggli, J.C.; Urwyler, A.; Pargger, H. Fulminant neuroleptic malignant syndrome after perioperative withdrawal of antiParkinsonian medication. Br. J. Anaesth. 2004, 93, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, A.; Cicek, M.; Gonenc Cekic, O.; Gunaydin, M.; Aykut, D.S.; Tatli, O.; Karaca, Y.; Arici, M.A. A retrospective analysis of cases with neuroleptic malignant syndrome and an evaluation of risk factors for mortality. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 17, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, X.; Geng, X. Dyskinesia-hyperpyrexia syndrome in Parkinson’s disease triggered by overdose of levodopa—A case report and literature review. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1323717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Horseman, M.; Panahi, L.; Udeani, G.; Tenpas, A.S.; Verduzco, R., Jr.; Patel, P.H.; Bazan, D.Z.; Mora, A.; Samuel, N.; Mingle, A.C.; et al. Drug-Induced Hyperthermia Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e27278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hospers, L.; Dillon, G.A.; McLachlan, A.J.; Alexander, L.M.; Kenney, W.L.; Capon, A.; Ebi, K.L.; Ashworth, E.; Jay, O.; Mavros, Y. The effect of prescription and over-the-counter medications on core temperature in adults during heat stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 77, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montastruc, J.L.; Durrieu, G. Drug-induced hypohidrosis and anhidrosis: Analysis of the WHO pharmacovigilance database 2000–2020. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 78, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artusi, C.A.; Merola, A.; Espay, A.J.; Zibetti, M.; Romagnolo, A.; Lanotte, M.; Lopiano, L. Parkinsonism-hyperpyrexia syndrome and deep brain stimulation. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 2780–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, T.Y.; Manninen, P.; Kalia, S.K.; Venkatraghavan, L. In reply: Parkinsonism-hyperthermia syndrome and deep brain stimulation. Can. J. Anaesth. 2017, 64, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroff, S.N. Parkinsonism-hyperthermia syndrome and deep brain stimulation. Can. J. Anaesth. 2017, 64, 675–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, T.Y.; Manninen, P.; Kalia, S.K.; Venkatraghavan, L. Anesthesia considerations for patients with an implanted deep brain stimulator undergoing surgery: A review and update. Can. J. Anaesth. 2017, 64, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renga, V.; Hickey, W.F.; Bernat, J.L. Spontaneous periodic hypothermia in Parkinson disease with hypothalamic involvement. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2017, 7, 538–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Bromocriptine-induced hypothermia. Neurology 1990, 40, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamp, D.; Paschali, M.; Bouanane, A.; Christl, J.; Supprian, T.; Meisenzahl-Lechner, E.; Kojda, G.; Lange-Asschenfeldt, C. Characteristics of antipsychotic drug-induced hypothermia in psychogeriatric inpatients. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 37, e2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Autonomic Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2020, 17, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pursiainen, V.; Haapaniemi, T.H.; Korpelainen, J.T.; Sotaniemi, K.A.; Myllyla, V.V. Sweating in Parkinsonian patients with wearing-off. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, R.F.; Sucha, E.L. “On-off”-induced lethal hyperthermia. Mov. Disord. 1989, 4, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, P.A. Evaluation of sudomotor function. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2004, 115, 1506–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipp, A.; Sandroni, P.; Ahlskog, J.E.; Fealey, R.D.; Kimpinski, K.; Iodice, V.; Gehrking, T.L.; Weigand, S.D.; Sletten, D.M.; Gehrking, J.A.; et al. Prospective differentiation of multiple system atrophy from Parkinson disease, with and without autonomic failure. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doppler, K. Detection of Dermal Alpha-Synuclein Deposits as a Biomarker for Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2021, 11, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, C.H.; Levine, T.; Adler, C.; Bellaire, B.; Wang, N.; Stohl, J.; Agarwal, P.; Aldridge, G.M.; Barboi, A.; Evidente, V.G.H.; et al. Skin Biopsy Detection of Phosphorylated α-Synuclein in Patients With Synucleinopathies. JAMA 2024, 331, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Yang, D.; Yang, H.J.; Kim, H.A.; Kim, S.; Heo, D.; Park, J.H.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, T.K. Quantitative autonomic function test in differentiation of multiple system atrophy from idiopathic Parkinson disease. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 1919–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buchmann, S.J.; Penzlin, A.I.; Kubasch, M.L.; Illigens, B.M.; Siepmann, T. Assessment of sudomotor function. Clin. Auton. Res. 2019, 29, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttmann, L. The management of the quinizarin sweat test (Q.S.T.). Postgrad. Med. J. 1947, 23, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fealey, R.D.; Low, P.A.; Thomas, J.E. Thermoregulatory sweating abnormalities in diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1989, 64, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coon, E.A.; Fealey, R.D.; Sletten, D.M.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Benarroch, E.E.; Sandroni, P.; Low, P.A.; Singer, W. Anhidrosis in multiple system atrophy involves pre- and postganglionic sudomotor dysfunction. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Idiaquez, J.; Casar, J.C.; Fadic, R.; Iturriaga, R. Sympathetic and electrochemical skin responses in the assessment of sudomotor function: A comparative study. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2023, 53, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenning, G.K.; Stankovic, I.; Vignatelli, L.; Fanciulli, A.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; Seppi, K.; Palma, J.A.; Meissner, W.G.; Krismer, F.; Berg, D.; et al. The Movement Disorder Society Criteria for the Diagnosis of Multiple System Atrophy. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 1131–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haapaniemi, T.H.; Korpelainen, J.T.; Tolonen, U.; Suominen, K.; Sotaniemi, K.A.; Myllyla, V.V. Suppressed sympathetic skin response in Parkinson disease. Clin. Auton. Res. 2000, 10, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikkawa, Y.; Asahina, M.; Suzuki, A.; Hattori, T. Cutaneous sympathetic function and cardiovascular function in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2003, 10, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.C.; Huang, C.C.; Lai, Y.R.; Lien, C.Y.; Cheng, B.C.; Kung, C.T.; Chiang, Y.F.; Lu, C.H. Assessing the Feasibility of Using Electrochemical Skin Conductance as a Substitute for the Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test in the Composite Autonomic Scoring Scale and Its Correlation with Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale 31 in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubasch, M.L.; Kubasch, A.S.; Torres Pacheco, J.; Buchmann, S.J.; Illigens, B.M.; Barlinn, K.; Siepmann, T. Laser Doppler Assessment of Vasomotor Axon Reflex Responsiveness to Evaluate Neurovascular Function. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Someren, E.J.; Dekker, K.; Te Lindert, B.H.; Benjamins, J.S.; Moens, S.; Migliorati, F.; Aarts, E.; van der Sluis, S. The experienced temperature sensitivity and regulation survey. Temperature 2016, 3, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Siepmann, T.; Gibbons, C.H.; Illigens, B.M.; Lafo, J.A.; Brown, C.M.; Freeman, R. Quantitative pilomotor axon reflex test: A novel test of pilomotor function. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nyein, H.Y.Y.; Bariya, M.; Tran, B.; Ahn, C.H.; Brown, B.J.; Ji, W.; Davis, N.; Javey, A. A wearable patch for continuous analysis of thermoregulatory sweat at rest. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, F.; Li, C.H.; Wang, J.W.; Han, C.L.; Fan, S.Y.; Gao, D.M.; Xing, Y.J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, J.G.; et al. Subthalamic nucleus-deep brain stimulation improves autonomic dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yavasoglu, N.G.; Comoglu, S.S. The effect of subthalamic deep brain stimulation on autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: Clinical and electrophysiological evaluation. Neurol. Res. 2021, 43, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, F.; Davies, J.A.; Redfern, P.H. The mechanism of the hypothermic effect of amantadine in rats and mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1978, 30, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| QSART | TST | SSR | ESC (Sudoscan) | LDF/LDI | Sensitive Sweat/Spoon Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures/Target Pathway | Postganglionic sudomotor (ACh iontophoresis) | Entire efferent thermoregulatory pathway | Central + pre-/postganglionic sudomotor | Electrochemical skin conductance (reverse iontophoresis); composite sudomotor index; non-localizing. | Vasomotor C-fiber axon reflex | Low sweat detection (qualitative) |

| Sensitivity/Specificity | High; variable by site | High | Low–moderate for PD; amplitudes often preserved in PD but reduced/absent in MSA/PN; non-localizing. | High for MSA/PN; lower for PD | Moderate; research-based | Low–Moderate |

| Lesion Localizing | Yes (postganglionic) | Yes (with QSART) | No | No | No | No |

| Lab Required | Yes | Yes | No (basic EMG) | No | Yes (research) | No |

| Specialized Equipment | QSART device, climate control | Heat chamber, imaging | EMG machine | ESC device | Laser Doppler | Minimal |

| Trained Personnel Needed | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Minimal | Yes | Minimal |

| Estimated Cost | High | High | Low | Moderate | High | Very Low |

| Utility Notes | Sensitive to distal PD patterns; tracks progression | Distinguishes PD (low % anhidrosis) from MSA (high %) | Often normal in PD; useful as a rapid screen; absent or markedly reduced responses should prompt evaluation for MSA or neuropathy | Fast PD screen; normal results don’t exclude dysfunction; interpret with clinical context/QSART-TST. | Limited clinical PD data; mostly investigational | Quick screen in low-resource PD settings |

| Non-Pharmacologic Measures | Pharmacologic Measures | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Non-Pharmacologic Measures | Pharmacologic Measures | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Non-Pharmacologic Measures | Pharmacologic Measures | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Non-Pharmacologic Measures | Pharmacologic Measures | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Non-Pharmacologic Measures | Pharmacologic Measures |

|---|---|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pressnell, Z.S.; Neilson, L.E.; Tupone, D.; Pfeiffer, R.F.; Safarpour, D. Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2025, 14, 1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231910

Pressnell ZS, Neilson LE, Tupone D, Pfeiffer RF, Safarpour D. Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231910

Chicago/Turabian StylePressnell, Zechariah S., Lee E. Neilson, Domenico Tupone, Ronald F. Pfeiffer, and Delaram Safarpour. 2025. "Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives" Cells 14, no. 23: 1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231910

APA StylePressnell, Z. S., Neilson, L. E., Tupone, D., Pfeiffer, R. F., & Safarpour, D. (2025). Thermoregulatory Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells, 14(23), 1910. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231910