Artificial Intelligence for Liquid Biopsy: FTIR Spectroscopy and Autoencoder-Based Detection of Cancer Biomarkers in Extracellular Vesicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

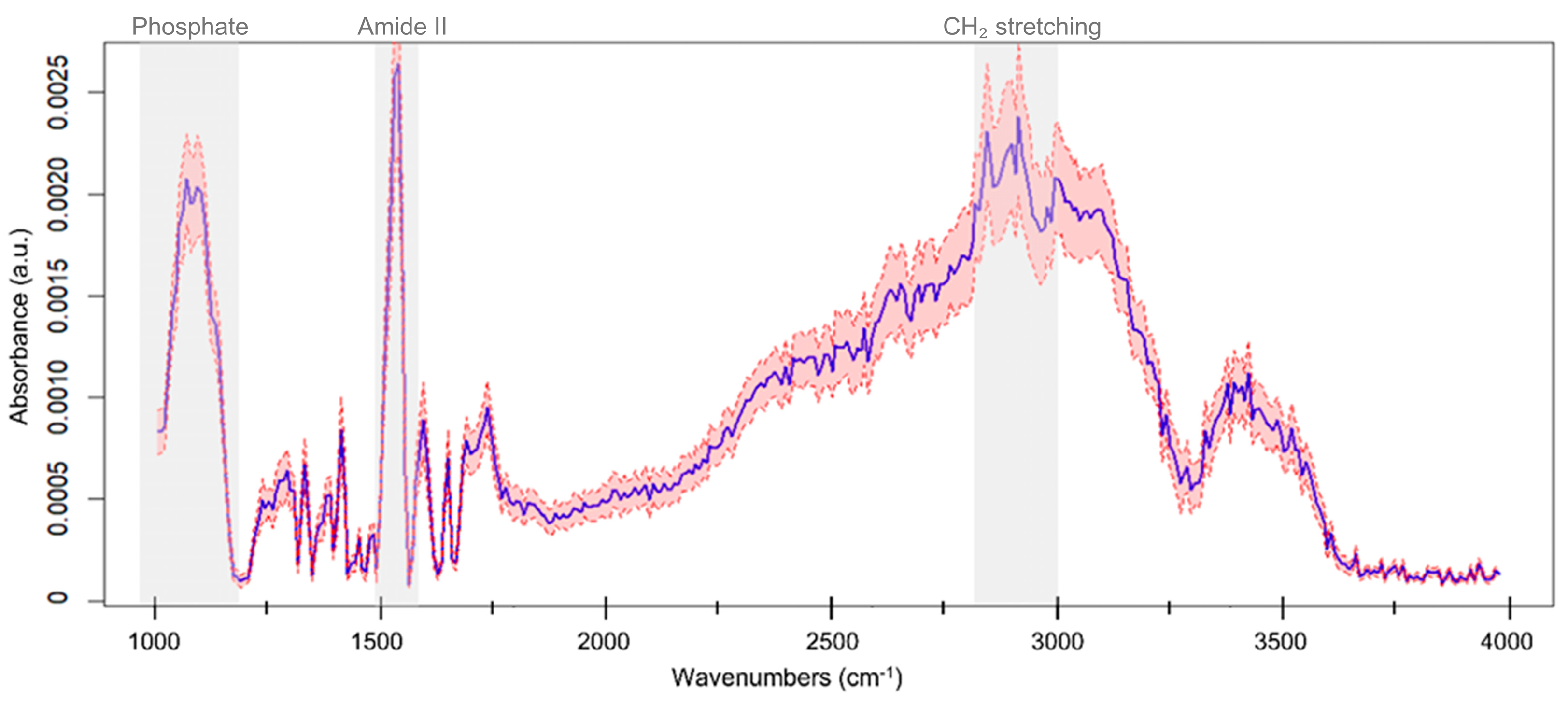

2.2. ATR-FTIR Spectral Acquisition and Pre-Processing

2.3. Autoencoder Modeling and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Design and Validation on Blood-Derived Components

3.2. Evaluation of EV Spectral Latent Features for Cancer Detection

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared |

| ATR | Attenuated Total Reflection |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| RBC | Red Blood Cells |

| RBC-G | Red Blood Cell Ghosts |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

| LOOCV | Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| AFP | Alpha-Fetoprotein |

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| EASL | European Association for the Study of the Liver |

References

- Urabe, F.; Kosaka, N.; Ito, K.; Kimura, T.; Egawa, S.; Ochiya, T. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Cancer. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019, 318, C29–C39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.G.; Gray, E.; Heman-Ackah, S.M.; Mäger, I.; Talbot, K.; El Andaloussi, S.; Wood, M.J.; Turner, M.R. Extracellular Vesicles in Neurodegenerative Disease—Pathogenesis to Biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 12, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciferri, M.C.; Quarto, R.; Tasso, R. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Tools: From Pre-Clinical to Clinical Applications. Biology 2021, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickhout, A.; Koenen, R.R. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers in Cardiovascular Disease; Chances and Risks. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thietart, S.; Rautou, P.-E. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers in Liver Diseases: A Clinician’s Point of View. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1507–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, R.E.; Korbie, D.; Hill, M.M.; Trau, M. Extracellular Vesicles as Circulating Cancer Biomarkers: Opportunities and Challenges. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, S.R.; Shah, K.M. Prospects and Current Challenges of Extracellular Vesicle-Based Biomarkers in Cancer. Biology 2024, 13, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, R.; Romanò, S.; Mazzini, A.; Jovanović, S.; Nocca, G.; Campi, G.; Papi, M.; De Spirito, M.; Di Giacinto, F.; Ciasca, G. Recent Advances in the Label-Free Characterization of Exosomes for Cancer Liquid Biopsy: From Scattering and Spectroscopy to Nanoindentation and Nanodevices. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Yu, L.; Ma, T.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Sun, Y.; Shi, H. Small Extracellular Vesicles Isolation and Separation: Current Techniques, Pending Questions and Clinical Applications. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklander, O.P.B.; Bostancioglu, R.B.; Welsh, J.A.; Zickler, A.M.; Murke, F.; Corso, G.; Felldin, U.; Hagey, D.W.; Evertsson, B.; Liang, X.-M. Systematic Methodological Evaluation of a Multiplex Bead-Based Flow Cytometry Assay for Detection of Extracellular Vesicle Surface Signatures. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinestrosa, J.P.; Kurzrock, R.; Lewis, J.M.; Schork, N.J.; Schroeder, G.; Kamat, A.M.; Lowy, A.M.; Eskander, R.N.; Perrera, O.; Searson, D. Early-Stage Multi-Cancer Detection Using an Extracellular Vesicle Protein-Based Blood Test. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihály, J.; Deák, R.; Szigyártó, I.C.; Bóta, A.; Beke-Somfai, T.; Varga, Z. Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles by IR Spectroscopy: Fast and Simple Classification Based on Amide and C-H Stretching Vibrations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2017, 1859, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szentirmai, V.; Wacha, A.; Németh, C.; Kitka, D.; Rácz, A.; Héberger, K.; Mihály, J.; Varga, Z. Reagent-Free Total Protein Quantification of Intact Extracellular Vesicles by Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 4619–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, X.-L.; Ong, T.-A.; Lim, J.; Wood, B.; Lee, W.-L. Study of Prostate Cancer-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Urine Using IR Spectroscopy. Prog. Drug Discov. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, R.; Vaccaro, M.; Romanò, S.; Di Giacinto, F.; Papi, M.; Rapaccini, G.L.; De Spirito, M.; Miele, L.; Basile, U.; Ciasca, G. Machine Learning-Assisted FTIR Analysis of Circulating Extra-Cellular Vesicles for Cancer Liquid Biopsy. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, R.; Verdelli, F.; Niccolini, B.; Varca, S.; del Gaudio, A.; Di Giancito, F.; De Spirito, M.; Pea, M.; Giovine, E.; Notargiacomo, A. Exploring Novel Circulating Biomarkers for Liver Cancer through Extracellular Vesicle Characterization with Infrared Spectroscopy and Plasmonics. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1319, 342959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Santo, R.; Niccolini, B.; Romanò, S.; Vaccaro, M.; Di Giacinto, F.; De Spirito, M.; Ciasca, G. Advancements in Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy of Extracellular Vesicles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 305, 123346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, A.A.; North, N.M.; Fensore, C.M.; Velez-Alvarez, J.; Allen, H.C. Functional Group Identification for FTIR Spectra Using Image-Based Machine Learning Models. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 9711–9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, T.G.; Larios, G.; Marangoni, B.; Oliveira, S.L.; Cena, C.; do Nascimento Ramos, C.A. FTIR Spectroscopy with Machine Learning: A New Approach to Animal DNA Polymorphism Screening. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 261, 120036. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Cao, Z.; Murphy, A.; Qiao, Y. An Ensemble Machine Learning Method for Microplastics Identification with FTIR Spectrum. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlelmoula, A.; Catarino, S.O.; Minas, G.; Carvalho, V. A Review of Machine Learning Methods Recently Applied to FTIR Spectroscopy Data for the Analysis of Human Blood Cells. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelucci, U. An Introduction to Autoencoders. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.03898. [Google Scholar]

- Pinaya, W.H.L.; Vieira, S.; Garcia-Dias, R.; Mechelli, A. Autoencoders. In Machine Learning; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Grossutti, M.; D’Amico, J.; Quintal, J.; MacFarlane, H.; Quirk, A.; Dutcher, J.R. Deep Learning and Infrared Spectroscopy: Representation Learning with a β-Variational Autoencoder. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 5787–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Liu, X.; Cai, W.; Shao, X. Spectral Encoder to Extract the Features of Near-Infrared Spectra for Multivariate Calibration. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 3695–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-D.; Kwon, S.; Nam, H.; Chang, D.E. Semi-Supervised Autoencoder for Chemical Gas Classification with FTIR Spectrum. Sensors 2024, 24, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Llovet, J.M.; Yarchoan, M.; Mehta, N.; Heimbach, J.K.; Dawson, L.A.; Jou, J.H.; Kulik, L.M.; Agopian, V.G.; Marrero, J.A. AASLD Practice Guidance on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1922–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2016; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Konopka, T.; Konopka, M.T. R-Package: Umap. Unif. Manifold Approx. Proj. 2018, 836, 837. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Qian, J. Glmnet Vignette; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 9, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, X.; Turck, N.; Hainard, A.; Tiberti, N.; Lisacek, F.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Müller, M.; Siegert, S.; Doering, M.; Billings, Z. Package ‘PROC’. 2021. Available online: https://mirror.linux.duke.edu/pub/cran/web/packages/pROC/pROC.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. R Package, version 2.0.0. Package ‘ggplot2’. Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2016; pp. 1–189.

- Cacciarelli, D.; Kulahci, M. Hidden Dimensions of the Data: PCA vs Autoencoders. Qual. Eng. 2023, 35, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Sohng, W.; Lee, H.; Chung, H. Evaluation of an Autoencoder as a Feature Extraction Tool for Near-Infrared Spectroscopic Discriminant Analysis. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemzadeh, M.; Martinez-Calderon, M.; Otupiri, R.; Artuyants, A.; Lowe, M.; Ning, X.; Reategui, E.; Schultz, Z.D.; Xu, W.; Blenkiron, C. Deep Autoencoder as an Interpretable Tool for Raman Spectroscopy Investigation of Chemical and Extracellular Vesicle Mixtures. Biomed. Opt. Express 2024, 15, 4220–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.N.; Guerreiro, E.M.; Enciso-Martinez, A.; Kruglik, S.G.; Otto, C.; Snir, O.; Ricaud, B.; Hellesø, O.G. Identification of Extracellular Vesicles from Their Raman Spectra via Self-Supervised Learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U. Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV2023): From Basic to Advanced Approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocino, K.; Napodano, C.; Marino, M.; Di Santo, R.; Miele, L.; De Matthaeis, N.; Gulli, F.; Saporito, R.; Rapaccini, G.L.; Ciasca, G. A Comparative Study of Serum Angiogenic Biomarkers in Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocino, K.; Stefanile, A.; Basile, V.; Napodano, C.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Di Santo, R.; Callà, C.A.M.; Gulli, F.; Saporito, R.; Ciasca, G. Cytokines and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Biomarkers of a Deadly Embrace. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Wu, S.; Yu, Y.; Ming, X.; Li, S.; Zuo, X.; Tu, J. Current Status and Perspective Biomarkers in AFP Negative HCC: Towards Screening for and Diagnosing Hepatocellular Carcinoma at an Earlier Stage. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Gan, D.; Cao, X.; Han, M.; Du, H.; Ye, Y. The Threshold of Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) for the Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, J.; Ren, H.; Chen, T.; Gao, L.; Di, L.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, T.; Thakur, A. Combining Multiple Serum Biomarkers in Tumor Diagnosis: A Clinical Assessment. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 1, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, D.; Coppola, A.; Quagliarini, E.; Di Santo, R.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cammarata, R.; Laganà, A.; Papi, M.; Digiacomo, L.; Coppola, R. Multiplexed Detection of Pancreatic Cancer by Combining a Nanoparticle-Enabled Blood Test and Plasma Levels of Acute-Phase Proteins. Cancers 2022, 14, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, H.; Ali, M.J.; Susheela, A.T.; Khan, I.W.; Luna-Cuadros, M.A.; Khan, M.M.; Lau, D.T.-Y. Update on the Applications and Limitations of Alpha-Fetoprotein for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrtělka, O.; Králová, K.; Fousková, M.; Setnička, V. Comprehensive Assessment of the Role of Spectral Data Pre-Processing in Spectroscopy-Based Liquid Biopsy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 339, 126261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theakstone, A.G.; Rinaldi, C.; Butler, H.J.; Cameron, J.M.; Confield, L.R.; Rutherford, S.H.; Sala, A.; Sangamnerkar, S.; Baker, M.J. Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy of Biofluids: A Practical Approach. Transl. Biophotonics 2021, 3, e202000025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Predictive Modeling in Healthcare. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2022, 6, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnazzo, V.; Pignalosa, S.; Tagliaferro, M.; Gragnani, L.; Zignego, A.L.; Racco, C.; Di Biase, L.; Basile, V.; Rapaccini, G.L.; Di Santo, R. Exploratory Study of Extracellular Matrix Biomarkers for Non-Invasive Liver Fibrosis Staging: A Machine Learning Approach with XGBoost and Explainable AI. Clin. Biochem. 2025, 135, 110861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ninno, A.; Ciasca, G.; Gerardino, A.; Calandrini, E.; Papi, M.; De Spirito, M.; Nucara, A.; Ortolani, M.; Businaro, L.; Baldassarre, L. An Integrated Superhydrophobic-Plasmonic Biosensor for Mid-Infrared Protein Detection at the Femtomole Level. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 21337–21342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temperini, M.E.; Di Giacinto, F.; Romanò, S.; Di Santo, R.; Augello, A.; Polito, R.; Baldassarre, L.; Giliberti, V.; Papi, M.; Basile, U.; et al. Antenna-Enhanced Mid-Infrared Detection of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Human Cancer Cell Cultures. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Features | HCC N = 9 1 | Cirrhosis N = 16 1 | p-Value 2 | q-Value 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.010 | 0.041 |

| F5 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 0.011 | 0.041 |

| F10 | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 0.005 | 0.041 |

| F11 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.11 | 0.014 | 0.041 |

| F1 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.2 |

| F3 | −0.03 ± 0.01 | −0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.8 | >0.9 |

| F4 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| F6 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.14 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| F7 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.064 | 0.13 |

| F8 | 0.20 ± 0.10 | 0.27 ± 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| F9 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | −0.01 ± 0.04 | >0.9 | >0.9 |

| F12 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.07 ± 0.10 | 0.036 | 0.087 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Santo, R.; Niccolini, B.; Rosa, E.; De Spirito, M.; Pizzolante, F.; Pitocco, D.; Tartaglione, L.; Rizzi, A.; Basile, U.; Petito, V.; et al. Artificial Intelligence for Liquid Biopsy: FTIR Spectroscopy and Autoencoder-Based Detection of Cancer Biomarkers in Extracellular Vesicles. Cells 2025, 14, 1909. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231909

Di Santo R, Niccolini B, Rosa E, De Spirito M, Pizzolante F, Pitocco D, Tartaglione L, Rizzi A, Basile U, Petito V, et al. Artificial Intelligence for Liquid Biopsy: FTIR Spectroscopy and Autoencoder-Based Detection of Cancer Biomarkers in Extracellular Vesicles. Cells. 2025; 14(23):1909. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231909

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Santo, Riccardo, Benedetta Niccolini, Enrico Rosa, Marco De Spirito, Fabrizio Pizzolante, Dario Pitocco, Linda Tartaglione, Alessandro Rizzi, Umberto Basile, Valentina Petito, and et al. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence for Liquid Biopsy: FTIR Spectroscopy and Autoencoder-Based Detection of Cancer Biomarkers in Extracellular Vesicles" Cells 14, no. 23: 1909. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231909

APA StyleDi Santo, R., Niccolini, B., Rosa, E., De Spirito, M., Pizzolante, F., Pitocco, D., Tartaglione, L., Rizzi, A., Basile, U., Petito, V., Gasbarrini, A., Gigante, G., & Ciasca, G. (2025). Artificial Intelligence for Liquid Biopsy: FTIR Spectroscopy and Autoencoder-Based Detection of Cancer Biomarkers in Extracellular Vesicles. Cells, 14(23), 1909. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14231909