Chemically Defined, Efficient Megakaryocyte Production from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells

Highlights

- Butyzamide (MPL agonist) plus M-CSF efficiently generates hPSC-derived MKs, replacing TPO.

- PSC-MKs can be used as a source for disease modeling, mechanistic studies, and in vitro platelet production.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Differentiation

2.2. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.3. Ploidy Analysis

2.4. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.6. Mitochondrial Respiration Analysis

2.7. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

2.8. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

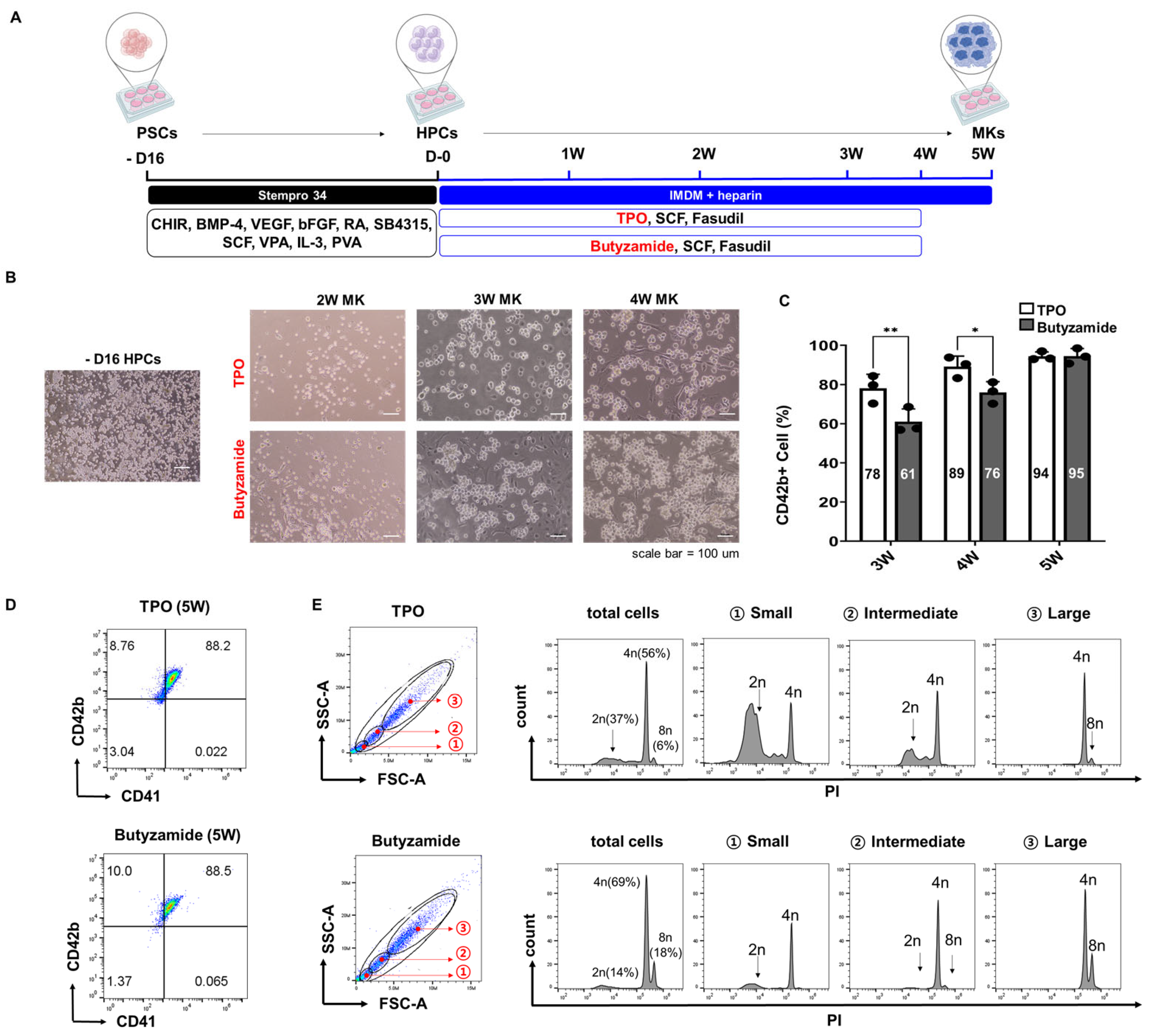

3.1. Butyzamide Enhances PSC-Derived Megakaryocyte Differentiation

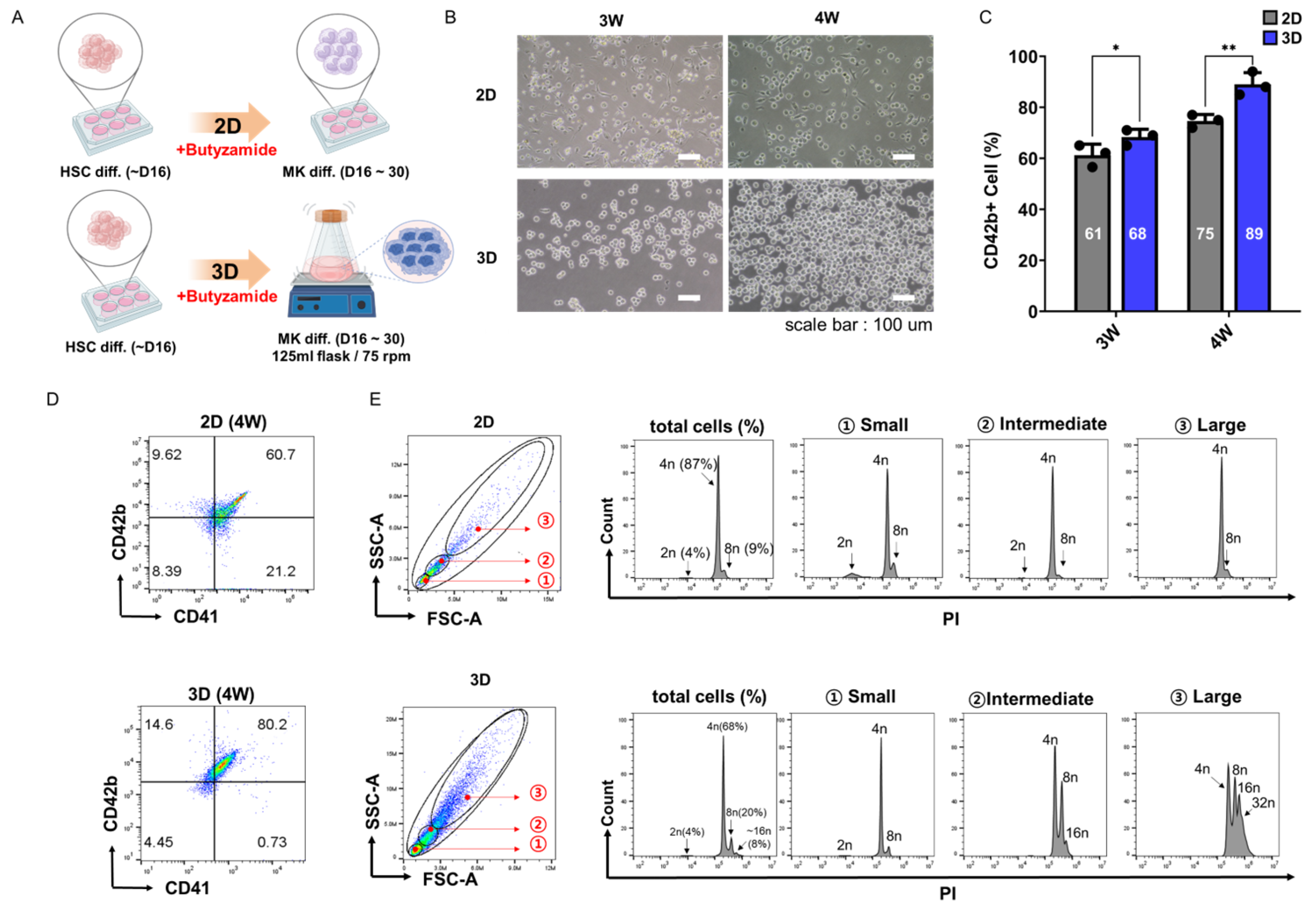

3.2. Three-Dimensional Suspension Culture Enhances PSC-Derived Megakaryocyte Differentiation

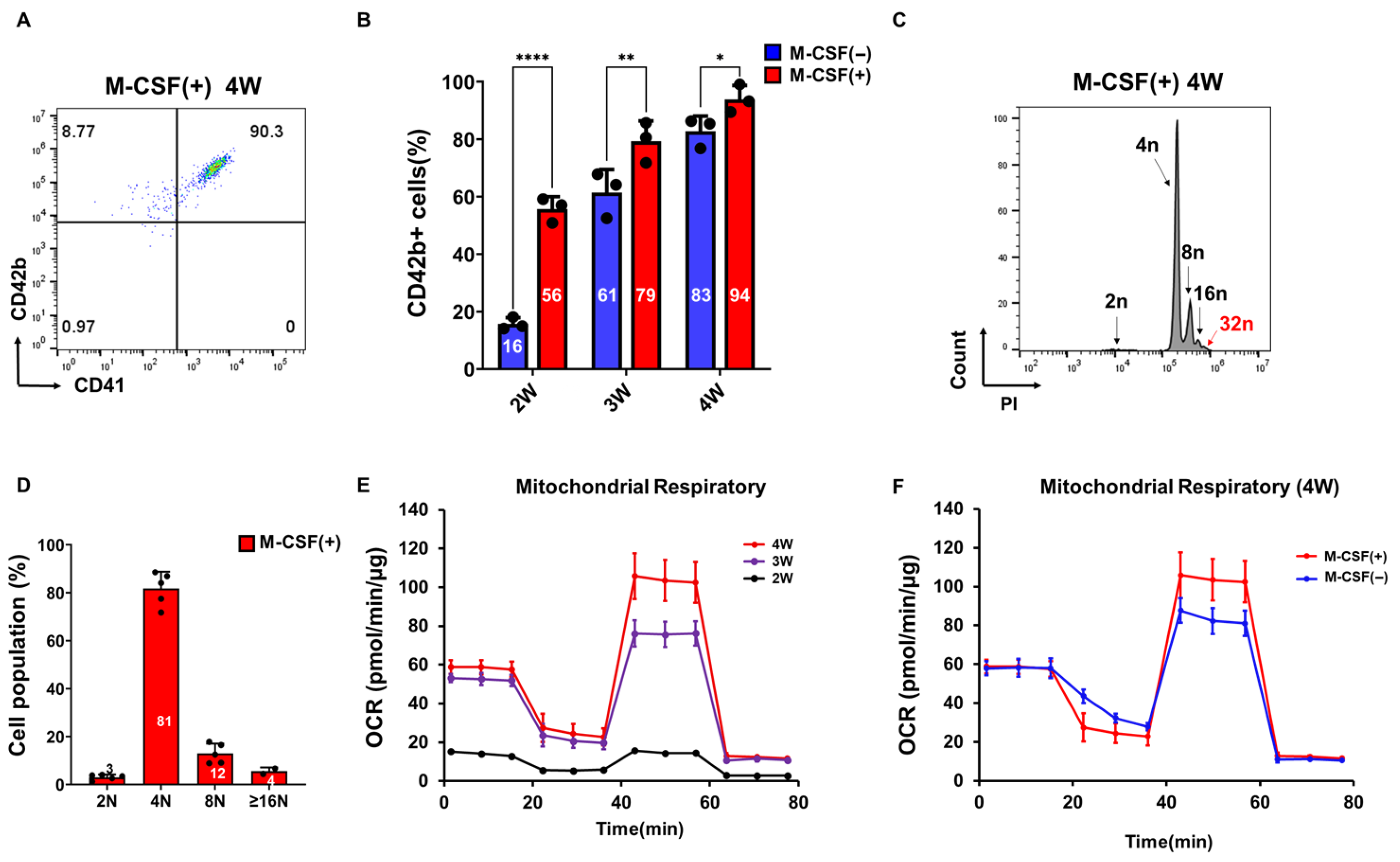

3.3. M-CSF Supplementation Accelerates PSC-Derived Megakaryocyte Differentiation

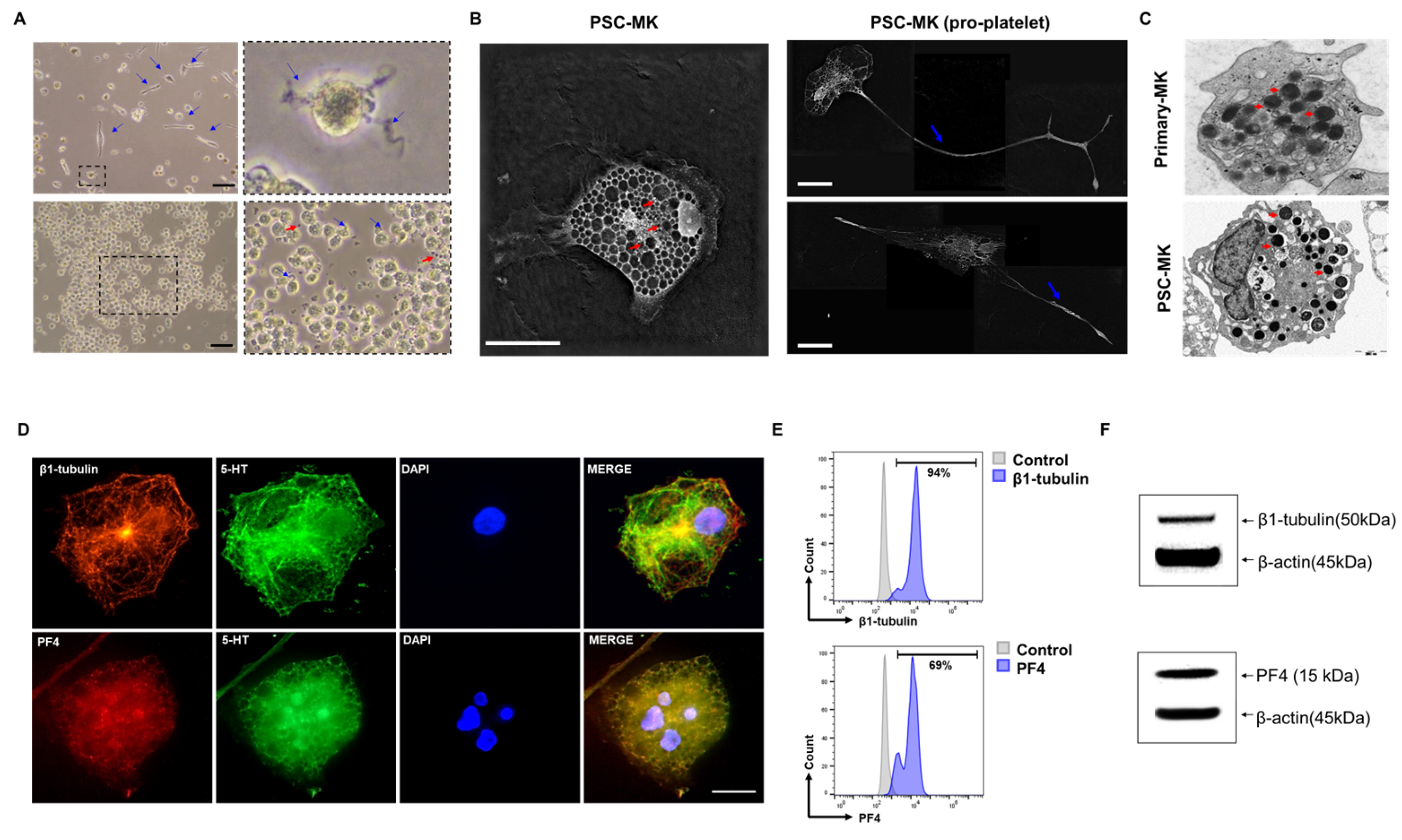

3.4. Multiple Assays Confirmed That the Cells Are PSC-Derived Megakaryocytes

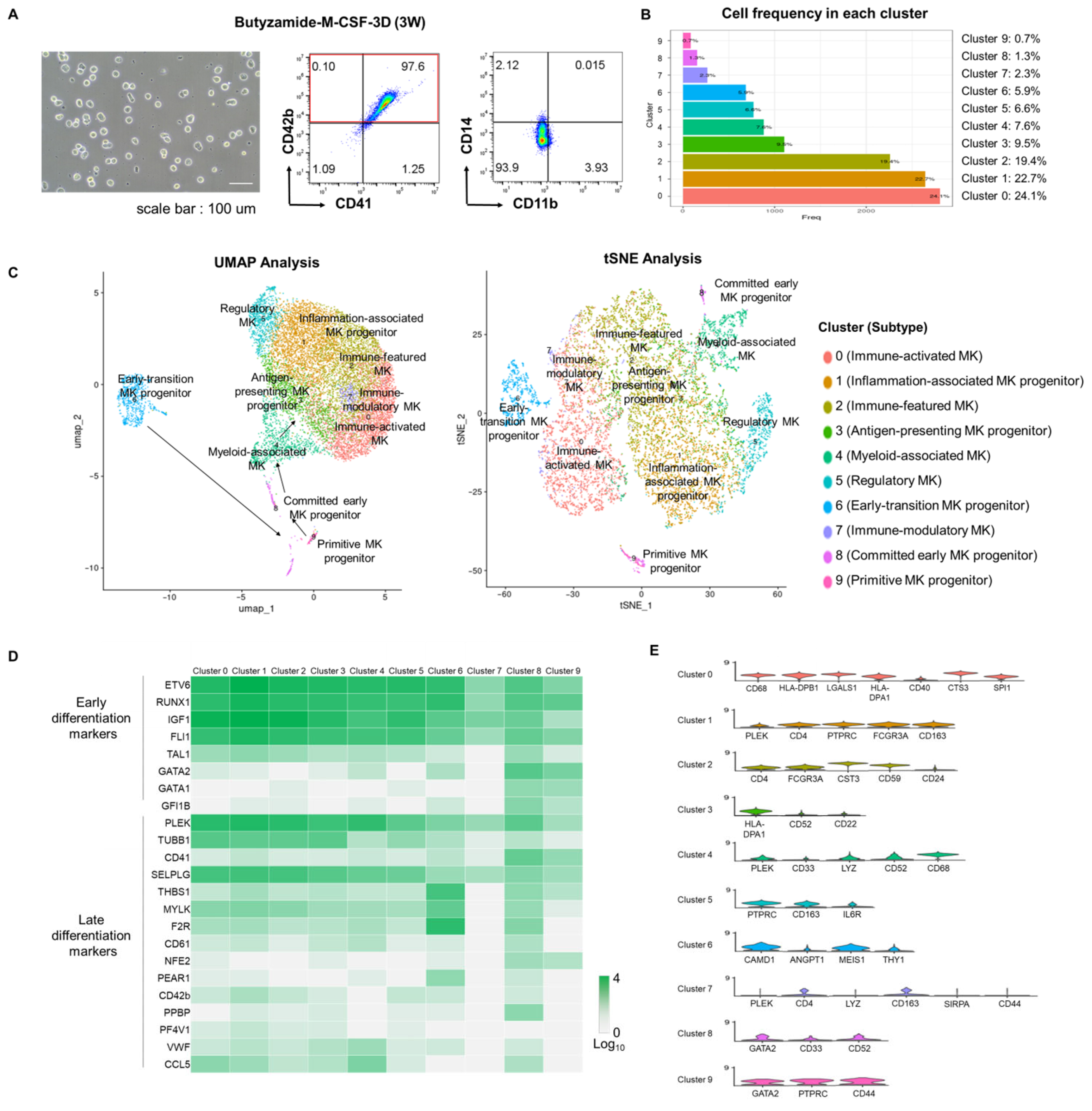

3.5. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Validation of Efficient Megakaryocytic Differentiation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MK | Megakaryocyte |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| SCF | Stem Cell Factor |

| FLT3L | Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase 3 Ligand |

| TPO | Thrombopoietin |

| MPL | Myeloproliferative Leukemia Virus Oncogene (Thrombopoietin Receptor) |

| M-CSF | Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| BSA | Bovine Serum Albumin |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| FC | Flow Cytometry |

| MFI | Mean Fluorescence Intensity |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| RT | Room Temperature |

| OCR | Oxygen Consumption Rate |

| ECAR | Extracellular Acidification Rate |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

| scRNA-seq | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| DEG | differentially expressed genes |

References

- Puhm, F.; Laroche, A.; Boilard, E. Diversity of megakaryocytes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 2088–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlus, K.R.; Italiano, J.E., Jr. The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharda, A.; Flaumenhaft, R. The life cycle of platelet granules. F1000Research 2018, 7, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuter, D.J. Managing thrombocytopenia associated with cancer chemotherapy. Oncology 2015, 29, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Woolthuis, C.M.; Park, C.Y. Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell commitment to the megakaryocyte lineage. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2016, 127, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Takayama, N.; Hirata, S.; Seo, H.; Endo, H.; Ochi, K.; Fujita, K.I.; Koike, T.; Harimoto, K.I.; Dohda, T.; et al. Expandable megakaryocyte cell lines enable clinically applicable generation of platelets from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, T.; Miyata, T.; Shirakawa, M.; Nagawa, H. Isolated spontaneous dissection of the splanchnic arteries. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 48, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddis, A.E. Megakaryopoiesis. Semin. Hematol. 2010, 47, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushansky, K. The molecular mechanisms that control thrombopoiesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3339–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Buduo, C.A.; Wray, L.S.; Tozzi, L.; Malara, A.; Chen, Y.; Ghezzi, C.E.; Smoot, D.; Sfara, C.; Antonelli, A.; Spedden, E.; et al. Programmable 3D silk bone marrow niche for platelet generation ex vivo and modeling of megakaryopoiesis pathologies. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2015, 125, 2254–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Dai, W.; Jiang, Y. Good manufacturing practice-grade of megakaryocytes produced by a novel ex vivo culturing platform. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 13, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogami, W.; Yoshida, H.; Koizumi, K.; Yamada, H.; Abe, K.; Arimura, A.; Yamane, N.; Takahashi, K.; Yamane, A.; Oda, A.; et al. The effect of a novel, small non-peptidyl molecule butyzamide on human thrombopoietin receptor and megakaryopoiesis. Haematologica 2008, 93, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Yamada, H.; Nogami, W.; Dohi, K.; Kurino-Yamada, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Gahara, Y.; Kitaura, M.; Hasegawa, M.; et al. Development of a new knock-in mouse model and evaluation of pharmacological activities of lusutrombopag, a novel, nonpeptidyl small-molecule agonist of the human thrombopoietin receptor c-Mpl. Exp. Hematol. 2018, 59, 30–39.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Sugimoto, N.; Shigemori, T.; Kato, Y.; Ohno, M.; Sakuma, S.; Ito, K.; Kumon, H.; Hirose, H.; et al. Turbulence activates platelet biogenesis to enable clinical scale ex vivo production. Cell 2018, 174, 636–648.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.; Huang, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Bai, L.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.C.; Hu, X.; et al. Biphasic modulation of insulin signaling enables highly efficient hematopoietic differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cheng, C.K.; Chan, H.Y.; Leung, K.T.; Li, C.K.; Chung, N.Y.; Pitts, H.A.; Tian, K.; Kam, Y.F. G3BP1:: CSF1R: A new and actionable gene fusion in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, S.; Lee, Y.; Choi, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Hwang, J.; Shin, J.; Dutton, J.R.; Seo, E.J.; Lee, B.H.; et al. The Rho-associated kinase inhibitor fasudil can replace Y-27632 for use in human pluripotent stem cell research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, M.; Takemoto, H.; Mori, T.; Okamoto, S.; Yamazaki, S. In vivo expansion of functional human hematopoietic stem progenitor cells by butyzamide. Int. J. Hematol. 2020, 111, 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Barrientos, D.; Pelayo, R.; Mayani, H. The hematopoietic microenvironment: A network of niches for the development of all blood cell lineages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2023, 114, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, A.; Monteiro, A.C.; Gonçalves-Silva, T.; Cordeiro-Spinetti, E.; Galvani, R.G.; Balduino, A. AT cell view of the bone marrow. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Hao, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Li, J. Strategies of macrophages to maintain bone homeostasis and promote bone repair: A narrative review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.L.T. C-mpl Expression in Osteoclast Progenitors: A Novel Role for Thrombopoietin in Regulating Osteoclast Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, S.; Huntly, B.J. Disordered signaling in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Hematol./Oncol. Clin. 2012, 26, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermouet, S.; Bigot-Corbel, E.; Gardie, B. Pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: Role and mechanisms of chronic inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 145293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zharikov, S.; Shiva, S. Platelet mitochondrial function: From regulation of thrombosis to biomarker of disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013, 41, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, J.P.; Figueredo, R.; Guan, Y.; Tomaiuolo, M.; Karamercan, M.A.; Welsh, J.; Selak, M.A.; Becker, L.B.; Sims, C. Increased platelet storage time is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired platelet function. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 184, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.L.; Corey, C.; White, P.; Watson, A.; Gladwin, M.T.; Simon, M.A.; Shiva, S. Platelets from pulmonary hypertension patients show increased mitochondrial reserve capacity. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e91415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Buduo, C.A.; Aguilar, A.; Soprano, P.M.; Bocconi, A.; Miguel, C.P.; Mantica, G.; Balduini, A. Latest culture techniques: Cracking the secrets of bone marrow to mass-produce erythrocytes and platelets ex vivo. Haematologica 2021, 106, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefrançais, E.; Ortiz-Muñoz, G.; Caudrillier, A.; Mallavia, B.; Liu, F.; Sayah, D.M.; Thornton, E.E.; Headley, M.B.; David, T.; Coughlin, S.R.; et al. The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature 2017, 544, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magid-Bernstein, J.; Beaman, C.B.; Carvalho-Poyraz, F.; Boehme, A.; Hod, E.A.; Francis, R.O.; Elkind, M.S.; Agarwal, S.; Park, S.; Claassen, J.; et al. Impacts of ABO-incompatible platelet transfusions on platelet recovery and outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2021, 137, 2699–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.E.; Chen, L.V.; Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Cheng, T.; Wang, Q.F.; Zhou, B.O. Differentiation route determines the functional outputs of adult megakaryopoiesis. Immunity 2024, 57, 478–494.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boilard, E.; Machlus, K.R. Location is everything when it comes to megakaryocyte function. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e144964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velten, L.; Haas, S.F.; Raffel, S.; Blaszkiewicz, S.; Islam, S.; Hennig, B.P.; Hirche, C.; Lutz, C.; Buss, E.C.; Nowak, D.; et al. Human haematopoietic stem cell lineage commitment is a continuous process. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psaila, B.; Barkas, N.; Iskander, D.; Roy, A.; Anderson, S.; Ashley, N.; Caputo, V.S.; Lichtenberg, J.; Loaiza, S.; Bodine, D.M.; et al. Single-cell profiling of human megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors identifies distinct megakaryocyte and erythroid differentiation pathways. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reagent/Material | Manufacturer | Research Grade Catalog No. | Alternative GMP Grade Catalog No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| stemMACS iPS-brew XF | Miltenyi (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) | 130-104-368 | 170-076-317 |

| Stempro 34 | Gibco | 10640-019 | A6636901 |

| IMDM (Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco Medium) | Gibco | 12440-053 | 12440-053 |

| Vitronectin | Gibco | A31804 | A14700 |

| Sodium citrate | Sigma-Aldrich | S4641 | S4641-25g |

| Fasudil HCl | AdooQ (Irvine, CA, USA) | A10381 | Y-27632, TB1254-GMP (TOCRIS) |

| CHIR-99021 | MedChemExpress (South Brunswick Township, NJ, USA) | HY-10182 | TB4423-GMP (R&D systems) |

| BMP-4 | Miltenyi | 130-111-165 | 314E-GMP (R&D systems) |

| bFGF | Peprotech (Cranbury, NJ, USA) | 100-18b | GMP100-18B-025 |

| VEGF 165 | Miltenyi | 130-109-385 | BT-VEGF-GMP (R&D systems) |

| Retinoic acid | Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) | R2625 | HY-14649G (MedChemExpress) |

| SCF | Miltenyi | 130-096-695 | 170-076-149 |

| IL-3 | Miltenyi | 130-095-069 | 170-076-110 |

| VPA | Sigma | PHR1061 | 1708707 |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin, 100X | GeneDireX (Taoyuan City, Taiwan) | CC502-0100 | Gentamycin, 15750060 (Gibco) |

| Butyzamide | Selleckchem (TX, USA) | S6988 | HY-148748G (MedChemExpress) |

| M-CSF | Miltenyi | 130-096-492 | 170-076-172 |

| Human albumin 20% | SK Plasma (Andong, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea) | 50800231 | GMP Human AB Serum, HABS001-GMP-100mL (R&D systems) |

| PVA | Sigma-Aldrich | 363146 | 1548065 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.E.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.; Hwang, S.-B.; Choi, Y.B.; Han, J.; Jung, J.; Song, J.-w.; Joung, J.-G.; Ko, J.-J.; et al. Chemically Defined, Efficient Megakaryocyte Production from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells 2025, 14, 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221835

Kim JE, Lee Y, Kim Y, Hwang S-B, Choi YB, Han J, Jung J, Song J-w, Joung J-G, Ko J-J, et al. Chemically Defined, Efficient Megakaryocyte Production from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells. 2025; 14(22):1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221835

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jae Eun, Yeonmi Lee, Yonghee Kim, Sae-Byeok Hwang, Yoo Bin Choi, Jongsuk Han, Juyeol Jung, Jae-woo Song, Je-Gun Joung, Jeong-Jae Ko, and et al. 2025. "Chemically Defined, Efficient Megakaryocyte Production from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells" Cells 14, no. 22: 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221835

APA StyleKim, J. E., Lee, Y., Kim, Y., Hwang, S.-B., Choi, Y. B., Han, J., Jung, J., Song, J.-w., Joung, J.-G., Ko, J.-J., & Kang, E. (2025). Chemically Defined, Efficient Megakaryocyte Production from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cells, 14(22), 1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221835