Reduced RhoGDI2 Expression Disrupts Centrosome Functions and Promotes Mitotic Errors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Cells

2.2. siRNA Transfection and Nucleofection

2.3. Western Blotting

2.4. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

2.5. Proliferation Assay

2.6. BrdU Incorporation Assay

2.7. Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

2.8. GTPase Activity Assay

2.9. Immunofluorescence

2.10. Tumor Cell Killing Assay

3. Results

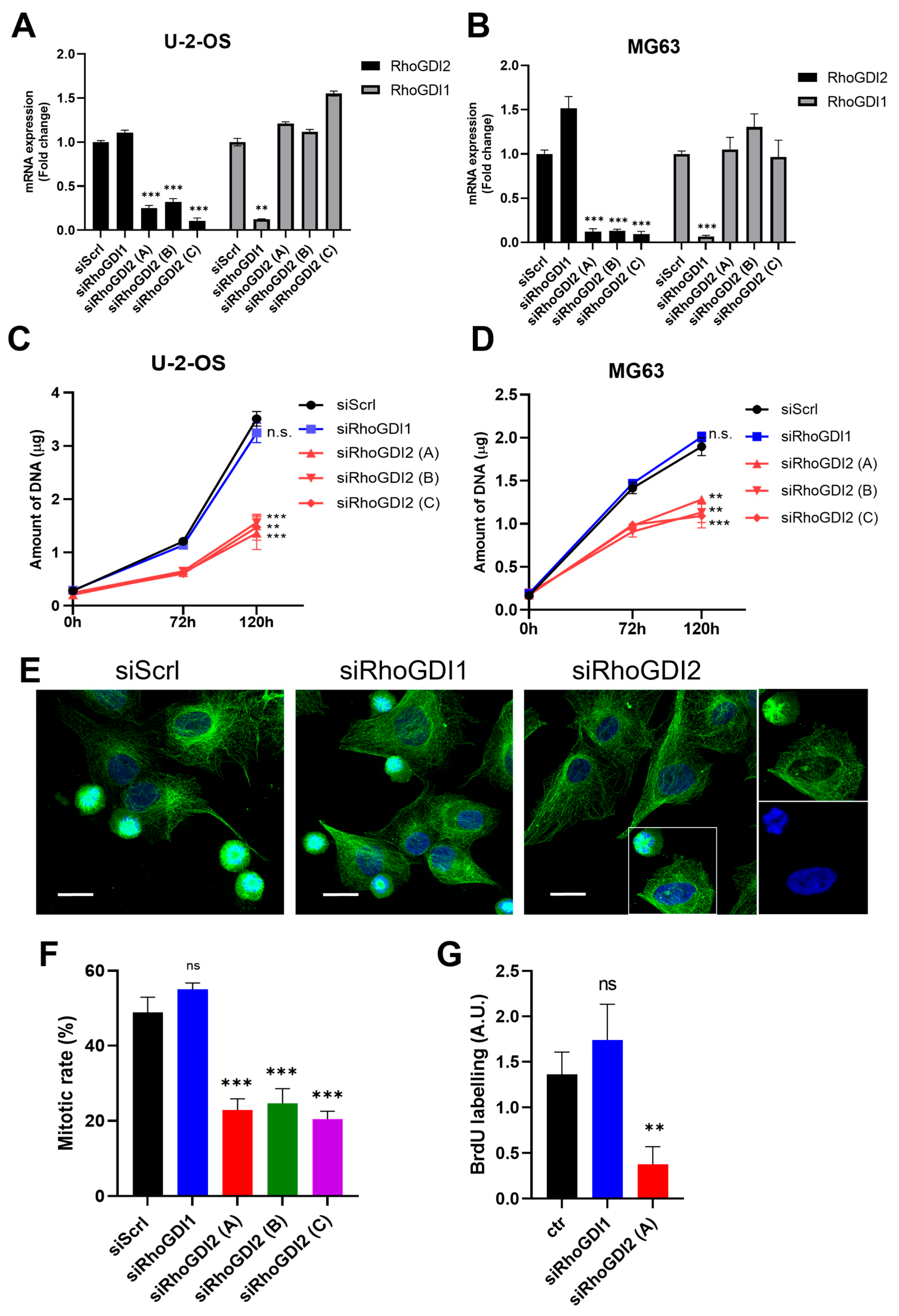

3.1. RhoGDI2 Silencing Repressed Cell Proliferation

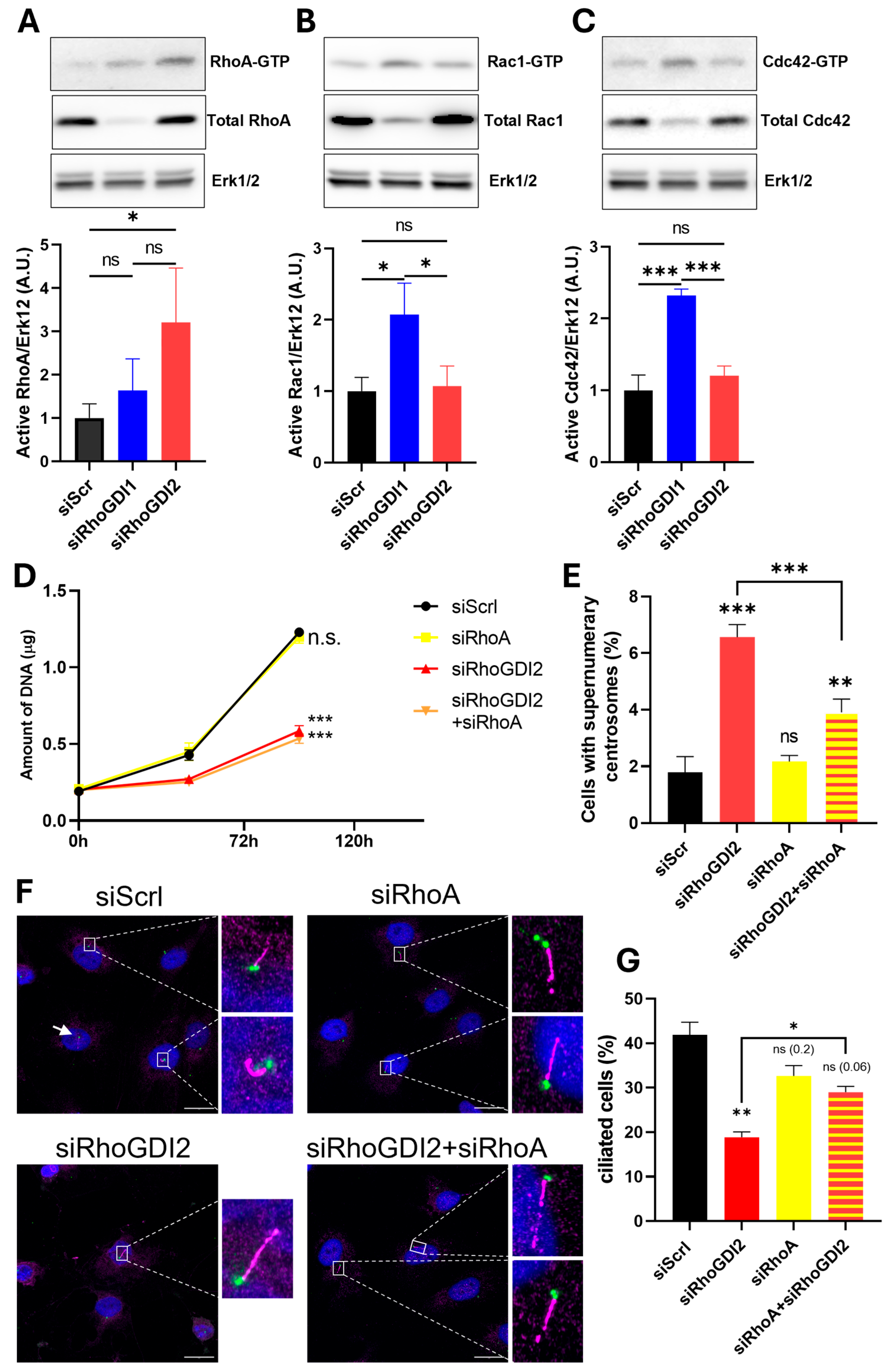

3.2. RhoGDI2 Silencing Increases Supernumerary Centrosomes

3.3. RhoGDI2 Silencing Reduces Ciliogenesis Through RhoA Activation

3.4. RhoGDI2 Silencing Reduced Tumor Cell Killing Ability of NK-92 Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hodge, R.G.; Ridley, A.J. Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mata, R.; Boulter, E.; Burridge, K. The ‘invisible hand’: Regulation of RHO GTPases by RHOGDIs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griner, E.M.; Theodorescu, D. The faces and friends of RhoGDI2. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012, 31, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moissoglu, K.; McRoberts, K.S.; Meier, J.A.; Theodorescu, D.; Schwartz, M.A. Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor 2 suppresses metastasis via unconventional regulation of RhoGTPases. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2838–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffers, H.; Nielsen, M.S.; Andersen, A.H.; Honore, B.; Madsen, P.; Vandekerckhove, J.; Celis, J.E. Identification of two human Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor proteins whose overexpression leads to disruption of the actin cytoskeleton. Exp. Cell Res. 1993, 209, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platko, J.V.; Leonard, D.A.; Adra, C.N.; Shaw, R.J.; Cerione, R.A.; Lim, B. A single residue can modify target-binding affinity and activity of the functional domain of the Rho-subfamily GDP dissociation inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2974–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Ryu, K.J.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.; Kim, S.H.; Han, H.; Kim, H.; Hong, K.S.; Song, C.Y.; Choi, Y.; et al. RhoGDI2-Mediated Rac1 Recruitment to Filamin A Enhances Rac1 Activity and Promotes Invasive Abilities of Gastric Cancer Cells. Cancers 2022, 14, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Kim, J.T.; Baek, K.E.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, H.G. Regulation of Rho GTPases by RhoGDIs in Human Cancers. Cells 2019, 8, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Colige, A.; Deroanne, C.F. The Dual Function of RhoGDI2 in Immunity and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giang Ho, T.T.; Stultiens, A.; Dubail, J.; Lapiere, C.M.; Nusgens, B.V.; Colige, A.C.; Deroanne, C.F. RhoGDIalpha-dependent balance between RhoA and RhoC is a key regulator of cancer cell tumorigenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 3263–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.T.; Merajver, S.D.; Lapiere, C.M.; Nusgens, B.V.; Deroanne, C.F. RhoA-GDP regulates RhoB protein stability. Potential involvement of RhoGDIalpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 21588–21598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroanne, C.; Vouret-Craviari, V.; Wang, B.; Pouyssegur, J. EphrinA1 inactivates integrin-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell spreading via the Rac/PAK pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, J.; Brohee, L.; Dupont, L.; Lefevre, C.; Peiffer, R.; Saarinen, A.M.; Peulen, O.; Bindels, L.; Liu, J.; Colige, A.; et al. Acidosis-induced regulation of adipocyte G0S2 promotes crosstalk between adipocytes and breast cancer cells as well as tumor progression. Cancer Lett. 2023, 569, 216306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarca, C.; Paigen, K. A simple, rapid, and sensitive DNA assay procedure. Anal. Biochem. 1980, 102, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deroanne, C.F.; Colige, A.C.; Nusgens, B.V.; Lapiere, C.M. Modulation of expression and assembly of vinculin during in vitro fibrillar collagen-induced angiogenesis and its reversal. Exp. Cell Res. 1996, 224, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nys, G.; Cobraiville, G.; Fillet, M. Multidimensional performance assessment of micro pillar array column chromatography combined to ion mobility-mass spectrometry for proteome research. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1086, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, E.E.; ten Klooster, J.P.; van Delft, S.; van der Kammen, R.A.; Collard, J.G. Rac downregulates Rho activity: Reciprocal balance between both GTPases determines cellular morphology and migratory behavior. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 147, 1009–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulter, E.; Estrach, S.; Garcia-Mata, R.; Feral, C.C. Off the beaten paths: Alternative and crosstalk regulation of Rho GTPases. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinchcombe, J.C.; Griffiths, G.M. Communication, the centrosome and the immunological synapse. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, M.A.; Theodorescu, D. RhoGDI signaling provides targets for cancer therapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ren, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Su, J.; Su, B.; Xia, H.; Liu, F.; Jiang, H.; et al. Knockdown of RhoGDI2 represses human gastric cancer cell proliferation, invasion and drug resistance via the Rac1/Pak1/LIMK1 pathway. Cancer Lett. 2020, 492, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.S.; Maeda, M.; Okamoto, M.; Fujii, M.; Fukutomi, R.; Hori, M.; Tatsuka, M.; Ota, T. Centrosomal localization of RhoGDIbeta and its relevance to mitotic processes in cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 42, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornens, M. Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002, 14, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, E.A.; Stearns, T. The centrosome cycle: Centriole biogenesis, duplication and inherent asymmetries. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, I. Centrosomes in mitotic spindle assembly and orientation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 66, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anvarian, Z.; Mykytyn, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, L.; Bost, F.; Mazure, N.M. Primary Cilium in Cancer Hallmarks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.Z.; Karbon, G.; Schuler, F.; Schapfl, M.A.; Weiss, J.G.; Petermann, P.Y.; Spierings, D.C.J.; Tijhuis, A.E.; Foijer, F.; Labi, V.; et al. Extra centrosomes delay DNA damage-driven tumorigenesis. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk0564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, K.; Ferland, R.J. Primary cilia proteins: Ciliary and extraciliary sites and functions. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 1521–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.E.L.; Lake, A.V.R.; Johnson, C.A. Primary Cilia, Ciliogenesis and the Actin Cytoskeleton: A Little Less Resorption, A Little More Actin Please. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 622822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, M.; Crowe, M.S.; Zheng, Y.; Vande Woude, G.F.; Fukasawa, K. RhoA and RhoC are both required for the ROCK II-dependent promotion of centrosome duplication. Oncogene 2010, 29, 6040–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, N.; Kowluru, A. Hyperglycemic Stress Induces Expression, Degradation, and Nuclear Association of Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor 2 (RhoGDIbeta) in Pancreatic beta-Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibbe, N.; Steinbacher, T.; Tellkamp, F.; Beckmann, N.; Brinkmann, F.; Stecher, M.; Gerke, V.; Niessen, C.M.; Ebnet, K. RhoGDI1 regulates cell-cell junctions in polarized epithelial cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1279723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douanne, T.; Stinchcombe, J.C.; Griffiths, G.M. Teasing out function from morphology: Similarities between primary cilia and immune synapses. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202102089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Unique Peptides | % Coverage | Score | Protein MW | Accession | Protein Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 87.5 | 276.2 | 23,044 | P52566 | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 2 |

| 9 | 34.8 | 99.7 | 21,849 | P63000 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 |

| 4 | 18.2 | 46.2 | 21,827 | P15153 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2 |

| 3 | 18.1 | 33.7 | 22,110 | P61586 | Transforming protein RhoA |

| 4 | 5.3 | 28.7 | 235,152 | Q8IZD9 | Dedicator of cytokinesis protein 3 |

| 4 | 5.3 | 26.2 | 224,984 | P11055 | Myosin-3 |

| 4 | 2.2 | 24.3 | 384,118 | A4UGR9 | Xin actin-binding repeat-containing protein 2 |

| 4 | 2.4 | 24.1 | 524,524 | Q96DT5 | Dynein heavy chain 11; axonemal |

| 4 | 7.0 | 23.8 | 215,310 | Q8TEP8 | Centrosomal protein of 192 kDa |

| 4 | 2.4 | 23.1 | 515,918 | Q9NYC9 | Dynein heavy chain 9; axonemal |

| 3 | 4.1 | 22.3 | 196,273 | Q15811 | Intersectin-1 |

| 3 | 1.7 | 21.6 | 404,166 | Q0VDD8 | Dynein heavy chain 14; axonemal |

| 3 | 12.2 | 21.6 | 69,618 | Q9GZS0 | Dynein intermediate chain 2; axonemal |

| 3 | 5.0 | 20.4 | 106,687 | O43182 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tripathi, M.; Garbacki, N.; Willems, J.; Cobraiville, G.; Fillet, M.; Colige, A.; Deroanne, C.F. Reduced RhoGDI2 Expression Disrupts Centrosome Functions and Promotes Mitotic Errors. Cells 2025, 14, 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221833

Tripathi M, Garbacki N, Willems J, Cobraiville G, Fillet M, Colige A, Deroanne CF. Reduced RhoGDI2 Expression Disrupts Centrosome Functions and Promotes Mitotic Errors. Cells. 2025; 14(22):1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221833

Chicago/Turabian StyleTripathi, Mudrika, Nancy Garbacki, Jérôme Willems, Gaël Cobraiville, Marianne Fillet, Alain Colige, and Christophe F. Deroanne. 2025. "Reduced RhoGDI2 Expression Disrupts Centrosome Functions and Promotes Mitotic Errors" Cells 14, no. 22: 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221833

APA StyleTripathi, M., Garbacki, N., Willems, J., Cobraiville, G., Fillet, M., Colige, A., & Deroanne, C. F. (2025). Reduced RhoGDI2 Expression Disrupts Centrosome Functions and Promotes Mitotic Errors. Cells, 14(22), 1833. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14221833