Halotolerant Bacterial Diversity Associated with Suaeda fruticosa (L.) Forssk. Improved Growth of Maize under Salinity Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Bacterial Strains

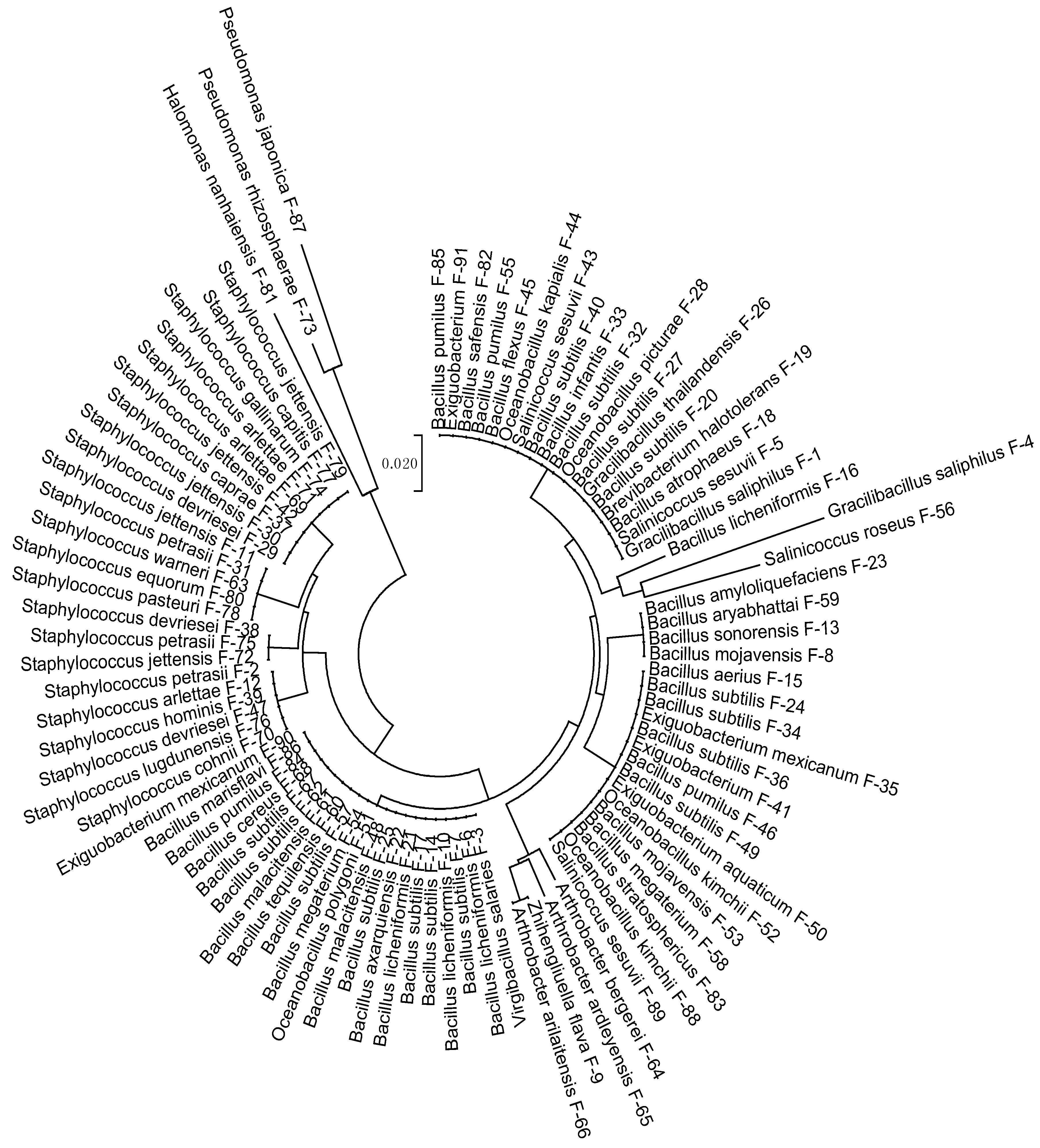

2.2. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing

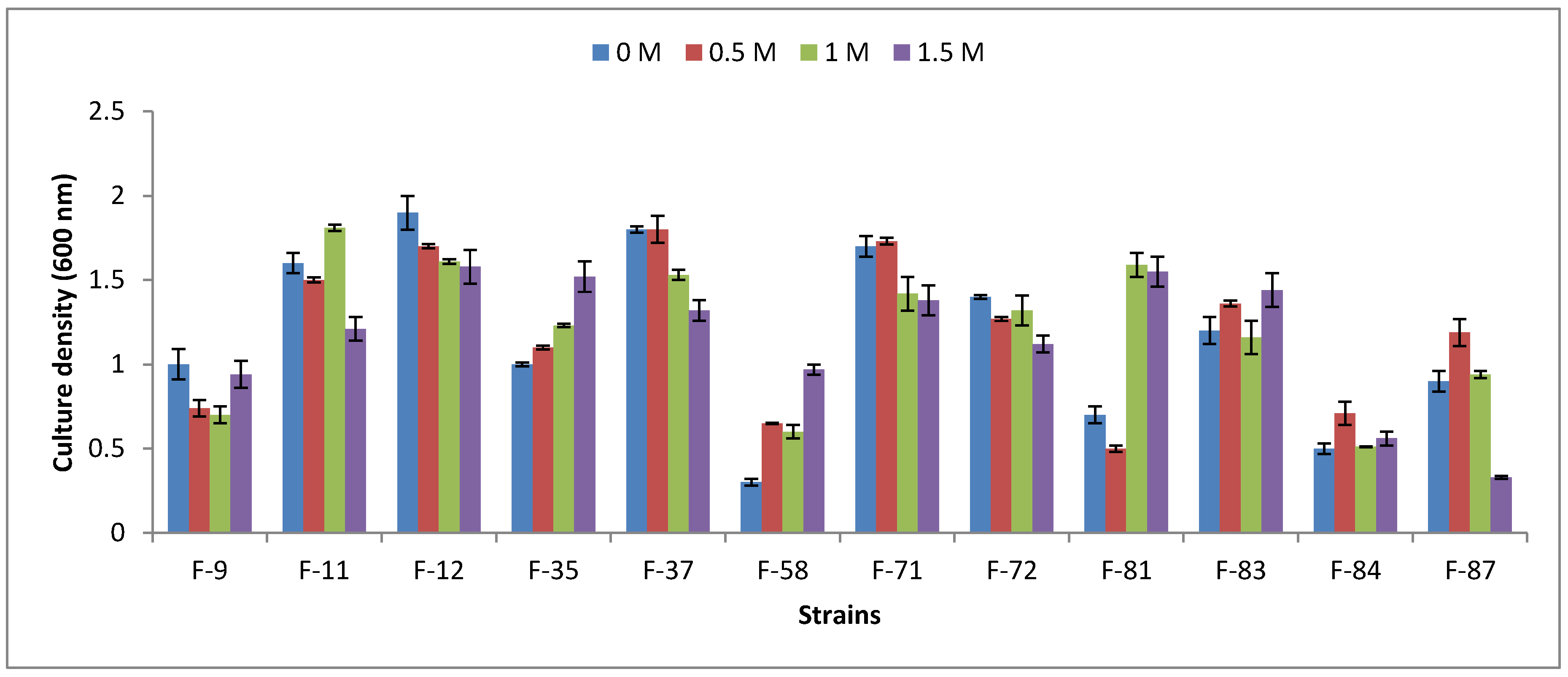

2.3. Halophility Assay

2.4. Plant-Growth-Promoting Traits

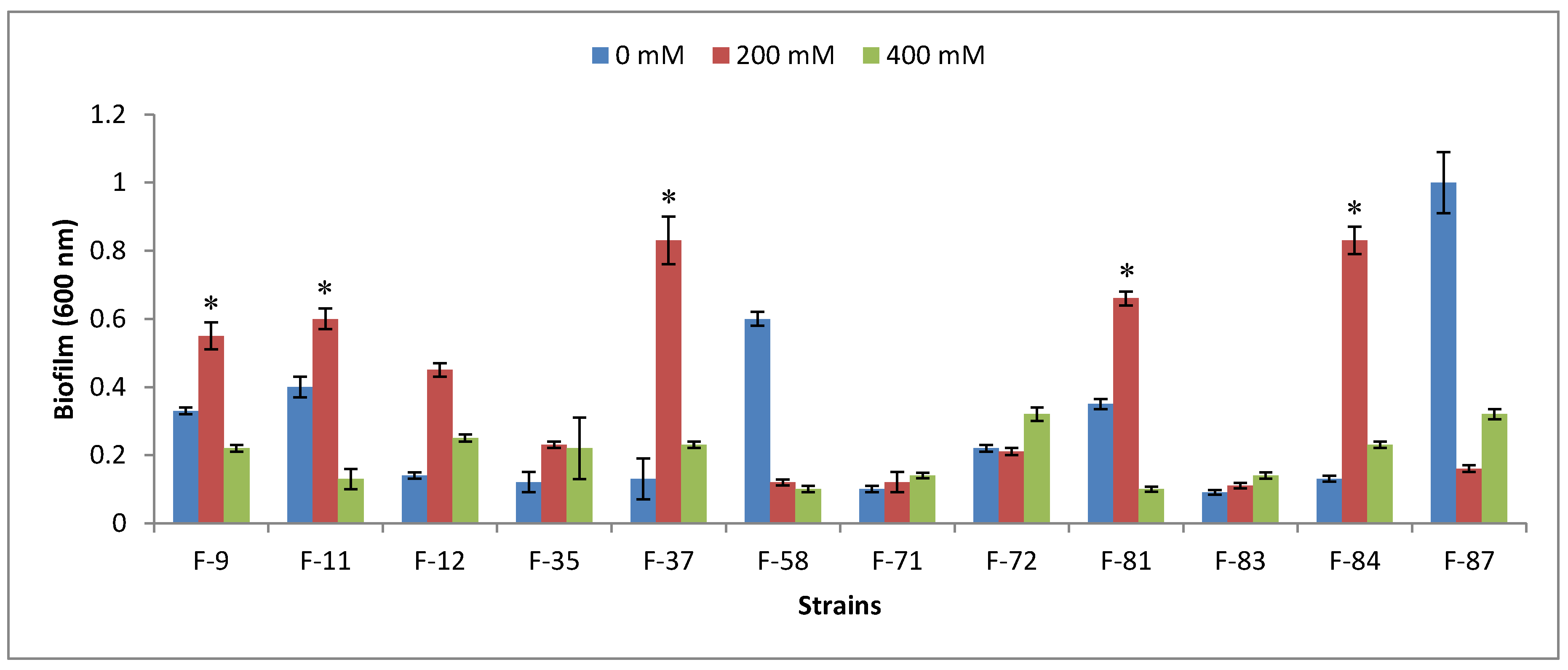

2.5. Biofilm Formation

2.6. In Vitro Plant Bioassay

2.7. Pot Trials with Salt Stress

2.8. Biochemical Analysis of Plants

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Strains Identification

3.2. Halophility Assay

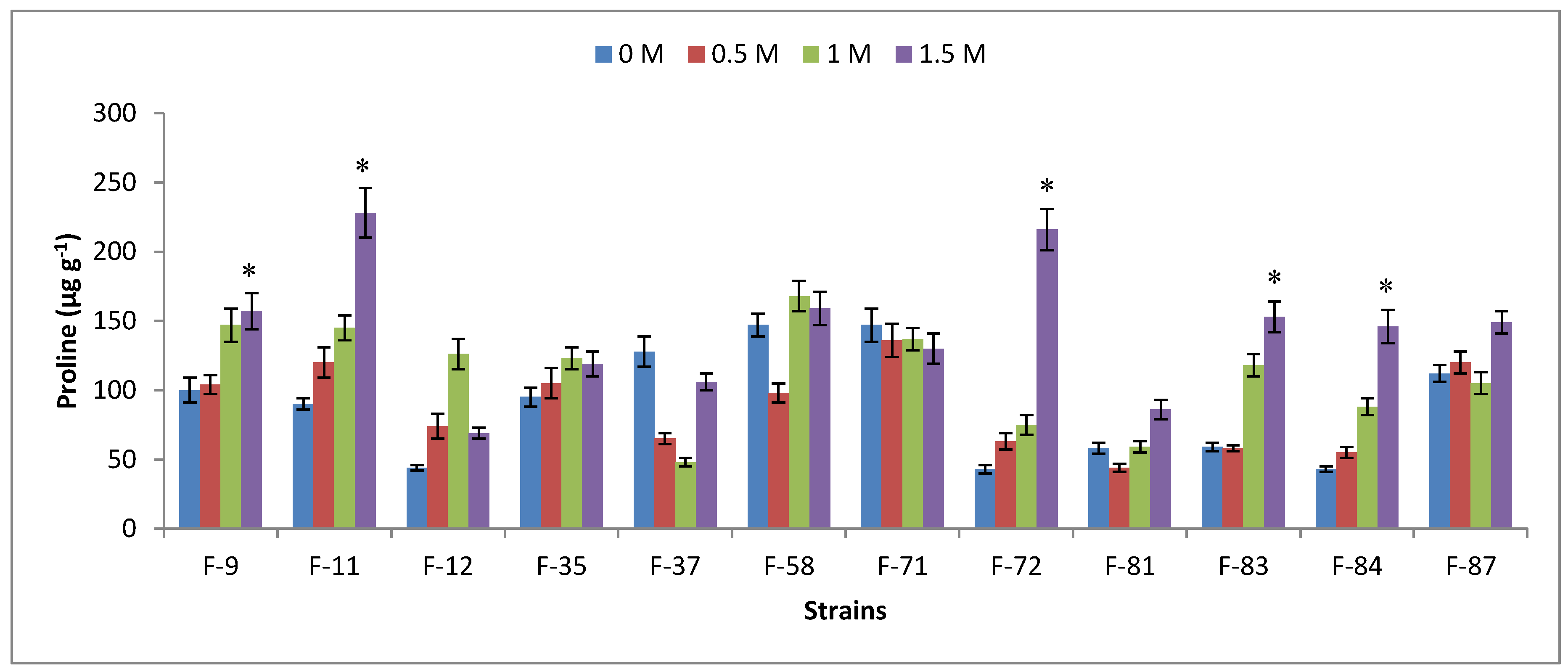

3.3. Plant-Growth-Promoting Traits

3.4. In Vitro Plant Bioassay

3.5. Pot Trials under Salt Stress

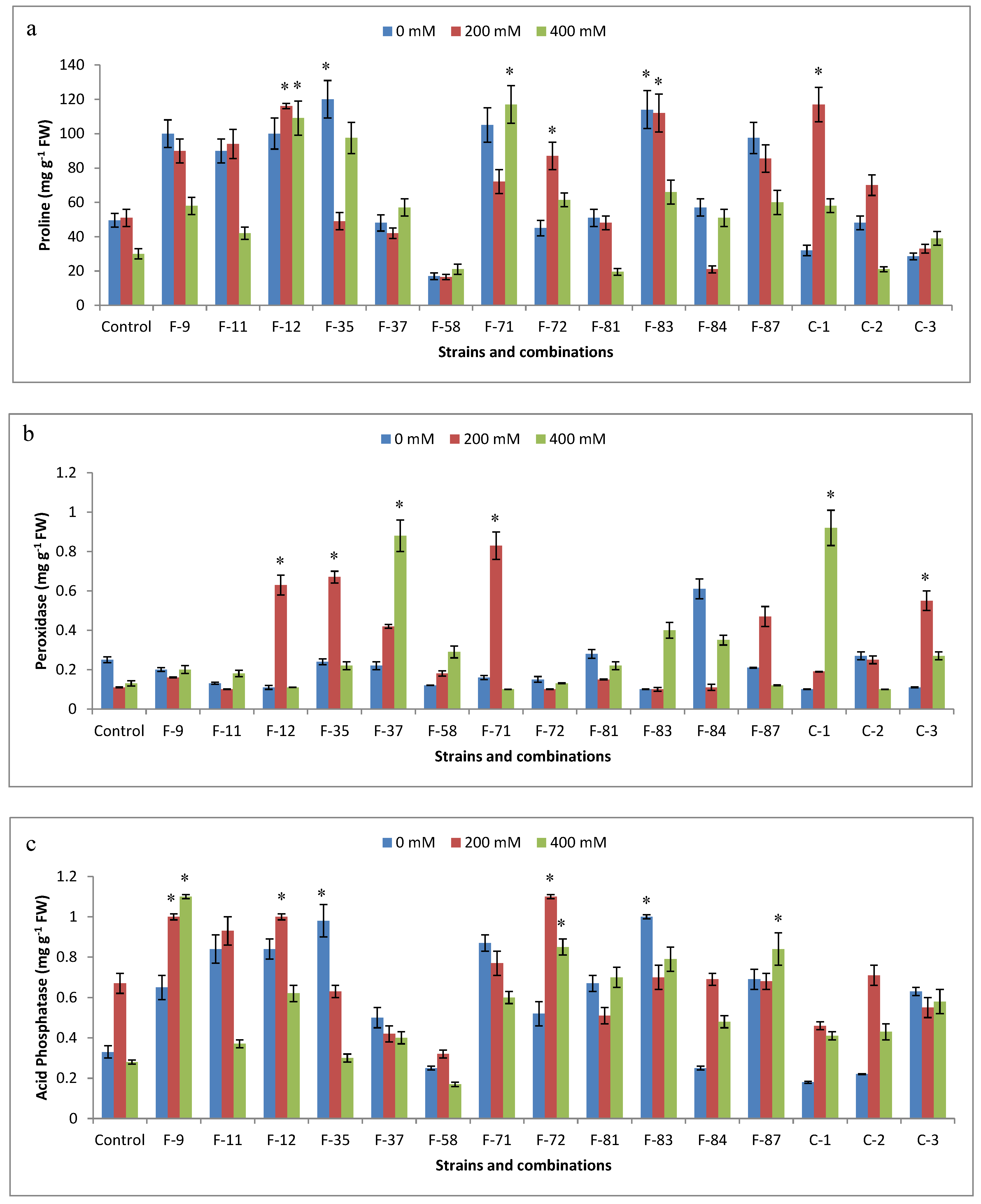

3.6. Antioxidant Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, K. Microbial and enzyme activities of saline and sodic Soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 706–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labidi, N.; Ammari, M.; Mssedi, D.; Benzerti, M.; Snoussi, S.; Abdelly, C. Salt excretion in Suaeda fruticosa. Acta Biol. Hung. 2010, 61, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Aziz, I. Salinity tolerance in some mangrove species from Pakistan. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 9, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Tuteja, N. Cold, salinity and drought stresses: An overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 444, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil salinity: A serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, A.; Hussain, T.; Gulzar, S.; Aziz, I.; Gul, B.; Khan, M.A. Salt tolerance of a cash crop halophyte Suaeda fruticosa: Biochemical response to salt and exogenous chemical treatments. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngumbi, E.; Kloepper, J. Bacterial-mediated drought tolerance: Current and future prospects. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 105, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kulkarni, J.; Jha, B. Halotolerant rhizobacteria promote growth and enhance salinity tolerance in peanut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raheem, A.; Ali, B. Halotolerant rhizobacteria: Beneficial plant metabolites and growth enhancement of Triticum aestivum L. in salt amended soils. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2015, 61, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, K.K.; Bhagwat, P.K.; Dandge, P.B. Plant growth-promoting characteristics of salt tolerant Enterobacter cloacae strain KBPD and its efficacy in amelioration of salt stress in Vigna radiata L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 36, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.W.; Bartel, B. Auxin: Regulation, action and interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, S.M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Naveed, M.; Asghar, H.N.; Arshad, M. Rhizobacteria capable of producing ACC-deaminase may mitigate salt stress in wheat. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R. Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Shi, X.; Lui, Z.; Li, C. Heterologous expression of ACC deaminase from Trichoderma asperellum improves the growth performance of Arabidopsis thaliana under normal and salt stress conditions. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 94, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Q.; Jiang, Z.W. Inoculation with plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) improves salt tolerance of maize seedling. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 64, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Bano, A. Isolation of plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria from rhizospheric soil of halophytes and their impact on maize (Zea mays L.) under induced salinity. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, G.; Murtaza, B.; Usman, H.M.; Ghafoor, A. Amelioration of saline-sodic soil using gypsum and low quality water in following sorghum-berseem crop rotation. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2013, 15, 640–648. [Google Scholar]

- Cappuccino, J.G.; Sherman, N. Microbiology: A Laboratory. In Microbial Populations in Soil: Enumeration, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Singapore, 2002; pp. 349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.L. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. In Similarity Analysis of rRNAs; Gerhardt, P., Murray, R.G.E., Wood, W.A., Krieg, N.R., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 625–700. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cha-Um, S.; Kirdmanee, C. Effect of salt stress on proline accumulation, photosynthetic ability and growth characters in two maize cultivars. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Borner, J. Enzymes involved in synthesis and breakdown of indoleacetic acid. Mod. Method Plant Anal. 1979, 7, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Pikovskaya, R.I. Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with viral activity of some microbial species. Mikrobiologiya 1948, 17, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chang, S.; Lin, L.; Li, Y.; An, Q. A colorimetric assay of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) based on ninhydrin reaction for rapid screening of bacteria containing ACC deaminase. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 53, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Christensen, G.D.; Simpson, W.; Younger, J.; Baddour, L.; Barrett, F.; Melton, D.; Beachey, E. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: A quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985, 22, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Racusen, D.; Foote, M. Protein synthesis in dark-grown bean leaves. Can. J. Bot. 1965, 43, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Rafique, N. Toxic effects of BaCl2 on germination, early seedling growth, soluble-proteins and acid-phosphatases in Zea mays L. Pak. J. Bot. 1987, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Demergasso, C.; Escudero, L.; Casamayor, E.O.; Chong, G.; Balagué, V.; Pedrós-Alió, C. Novelty and spatio-temporal heterogeneity in the bacterial diversity of hypersaline lake Tebenquiche (Salar de Atacama). Extremophiles 2008, 12, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roohi, A.; Ahmed, I.; Iqbal, M.; Jamil, M. Preliminary isolation and characterization of halotolerant and halophilic bacteria from salt mines of Karak, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2012, 44, 365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, D.; Dhandhukia, P.; Patel, P.; Thakker, J.N. Screening of PGPR from saline desert of Kutch: Growth promotion in Arachis hypogea by Bacillus licheniformis A2. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forni, C.; Duca, D.; Glick, B.R. Mechanisms of plant response to salt and drought stress and their alteration by rhizobacteria. Plant Soil 2017, 410, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Shaposhnikov, A.; Belimov, A.A.; Dodd, I.C.; Ali, B. Auxin production by rhizobacteria was associated with improved yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought stress. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2018, 64, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U.; Chakraborty, B.; Chakraborty, A.; Dey, P. Water stress amelioration and plant growth promotion in wheat plants by osmotic stress tolerant bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, B.; Aroca, R.; Barea, J.M.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M. Native arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi isolated from a saline habitat improved maize antioxidant systems and plant tolerance to salinity. Plant Sci. 2013, 201, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, F.; Ali, B. Efficacy of charcoal based formulations of Bacillus and Escherichia coli to enhance the growth and yield of Triticum aestivum L. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 10, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Defez, R.; Andreozzi, A.; Bianco, C. The overproduction of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in endophytes upregulates nitrogen fixation in both bacterial cultures and inoculated rice plants. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đorđević, S.; Stanojević, D.; Vidović, M.; Mandić, V.; Trajković, I. The use of bacterial indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) for reduce of chemical fertilizers doses. Hem. Ind. 2017, 71, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Jang, Y.; Lee, S.; Oh, B.; Chae, J.; Lee, K. Alleviation of salt stress by Enterobacter sp. EJ01 in tomato and Arabidopsis is accompanied by up-regulation of conserved salinity responsive factors in plants. Mol. Cells 2014, 37, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.; Singh, P.; Tiwari, R.; Meena, K.K.; Yandigeri, M.; Singh, D.P.; Arora, D.K. Salt-tolerant rhizobacteria-mediated induced tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and chemical diversity in rhizosphere enhance plant growth. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, M.; Raheem, A.; Ali, B. Phylogenetic diversity of drought tolerant Bacillus spp. and their growth stimulation of Zea mays L. under different water regimes. Res. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 12, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Orhan, F. Alleviation of salt stress by halotolerant and halophilic plant growth-promotingbacteria in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Jha, P.; Jha, P.N. The plant-growth-promoting bacterium Klebsiella sp. SBP-8 confers induced systemic tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) under salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 184, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tank, N.; Saraf, M. Salinity-resistant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria ameliorates sodium chloride stress on tomato plants. J. Plant Interact. 2010, 5, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qurashi, A.W.; Sabri, A.N. Bacterial exopolysaccharide and biofilm formation stimulate chickpea growth and soil aggregation under salt stress. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kasim, W.A.; Gaafar, R.M.; Abou-Ali, R.M.; Omar, M.N.; Hewait, H. Effect of biofilm forming growth promoting rhizobacteria on salinity tolerance in barley. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2016, 61, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S. No. | Strains | Identified as | Accessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F-1 | Gracilibacillus saliphilus F-1 | KT027652 |

| 2 | F-2 | Staphylococcus petrasii F-2 | KT027653 |

| 3 | F-3 | Virgibacillus salarius F-3 | KT027654 |

| 4 | F-4 | G. saliphilus F-4 | KT027655 |

| 5 | F-5 | Salinicoccus sesuvii F-5 | KT027656 |

| 6 | F-6 | Bacillus licheniformis F-6 | KT027657 |

| 7 | F-7 | B. subtilis F-7 | KT027658 |

| 8 | F-8 | B. mojavensis F-8 | KT027659 |

| 9 | F-9 | Zhihengliuella flava F-9 | KT027660 |

| 10 | F-10 | B. licheniformis F-10 | KT027661 |

| 11 | F-11 | S. jettensis F-11 | KT027662 |

| 12 | F-12 | S. arlettae F-12 | KT027663 |

| 13 | F-13 | B. sonorensis F-13 | KT027664 |

| 14 | F-14 | B. subtilis F-14 | KT027665 |

| 15 | F-15 | B. aerius F-15 | KT027666 |

| 16 | F-16 | B. licheniformis F-16 | KT027667 |

| 17 | F-17 | B. subtilis F-17 | KT027668 |

| 18 | F-18 | B. atrophaeus F-18 | KT027669 |

| 19 | F-19 | Brevibacterium halotolerans F-19 | KT027670 |

| 20 | F-20 | B. subtilis F-20 | KT027671 |

| 21 | F-21 | B. licheniformis F-21 | KT027672 |

| 22 | F-22 | B. axarquiensis F-22 | KT027673 |

| 23 | F-23 | B. amyloliquefaciens F-23 | KT027674 |

| 24 | F-24 | B. subtilis F-24 | KT027675 |

| 25 | F-25 | B. subtilis F-25 | KT027676 |

| 26 | F-26 | G. thailandensis F-26 | KT027677 |

| 27 | F-27 | B. subtilis F-27 | KT027678 |

| 28 | F-28 | Oceanobacillus picturae F-28 | KT027679 |

| 29 | F-29 | S. devriesei F-29 | KT027680 |

| 30 | F-30 | S. jettensis F-30 | KT027681 |

| 31 | F-31 | S. petrasii F-31 | KT027682 |

| 32 | F-32 | B. subtilis F-32 | KT027683 |

| 33 | F-33 | B. infantis F-33 | KT027684 |

| 34 | F-34 | B. subtilis F-32 | KT027685 |

| 35 | F-35 | Exiguobacterium mexicanum F-35 | KT027686 |

| 36 | F-36 | B. subtilis F-36 | KT027687 |

| 37 | F-37 | S. caprae F-37 | KT027688 |

| 38 | F-38 | S. devriesei F-38 | KT027689 |

| 39 | F-39 | S. hominis F-39 | KT027690 |

| 40 | F-83 | B. stratosphericus F-83 | KT027734 |

| 41 | F-84 | B. pumilus F-84 | KT027735 |

| 42 | F-85 | B. pumilus F-85 | KT027736 |

| 43 | F-86 | B. marisflavi F-86 | KT027737 |

| 44 | F-87 | Pseudomonas japonica F-87 | KT027738 |

| 45 | F-89 | Sal. sesuvii F-89 | KT027740 |

| S. No. | Strains | Identified as | Accessions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F-40 | Bacillus subtilis F-40 | KT027691 |

| 2 | F-41 | Exiguobacterium sp. F-41 | KT027692 |

| 3 | F-42 | Staphylococcus jettensis F-42 | KT027693 |

| 4 | F-43 | Salinicoccus sesuvii F-43 | KT027694 |

| 5 | F-44 | Oceanobacillus kapialis F-44 | KT027695 |

| 6 | F-45 | B. flexus F-45 | KT027696 |

| 7 | F-46 | B. pumilus F-46 | KT027697 |

| 8 | F-47 | S. devriesei F-47 | KT027698 |

| 9 | F-48 | B. malacitensis F-48 | KT027699 |

| 10 | F-49 | B. malacitensis F-49 | KT027700 |

| 11 | F-50 | E. aquaticum F-50 | KT027701 |

| 12 | F-51 | O. polygoni F-51 | KT027702 |

| 13 | F-52 | O. kimchii F-52 | KT027703 |

| 14 | F-53 | B. mojavensis F-53 | KT027704 |

| 15 | F-54 | B. megaterium F-54 | KT027705 |

| 16 | F-55 | B. pumilus F-55 | KT027706 |

| 17 | F-56 | Sal. roseus F-56 | KT027707 |

| 18 | F-57 | B. subtilis F-57 | KT027708 |

| 19 | F-58 | B. megaterium F-58 | KT027709 |

| 20 | F-59 | B. aryabhattai F-59 | KT027710 |

| 21 | F-60 | B. tequilensis F-60 | KT027711 |

| 22 | F-61 | B. malacitensis F-61 | KT027712 |

| 23 | F-62 | B. subtilis F-62 | KT027713 |

| 24 | F-63 | S. warneri F-63 | KT027714 |

| 25 | F-64 | Arthrobacter bergerei F-64 | KT027715 |

| 26 | F-65 | A. ardleyensis F-65 | KT027716 |

| 27 | F-66 | A. arilaitensis F-66 | KT027717 |

| 28 | F-67 | B. subtilis F-67 | KT027718 |

| 29 | F-68 | B. cereus F-68 | KT027719 |

| 30 | F-69 | S. arlettae F-69 | KT027720 |

| 31 | F-70 | S. cohnii F-70 | KT027721 |

| 32 | F-71 | S. arlettae F-71 | KT027722 |

| 33 | F-72 | S. jettensis F-72 | KT027723 |

| 34 | F-73 | Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae F-73 | KT027724 |

| 35 | F-74 | S. gallinarum F-74 | KT027725 |

| 36 | F-75 | S. petrasii F-75 | KT027726 |

| 37 | F-76 | S. lugdunensis F-76 | KT027727 |

| 38 | F-77 | S. capitis F-77 | KT027728 |

| 39 | F-78 | S. pasteuri F-78 | KT027729 |

| 40 | F-79 | S. jettensis F-79 | KT027730 |

| 41 | F-80 | S. equorum F-80 | KT027731 |

| 42 | F-81 | Halomonas nanhaiensis F-81 | KT027732 |

| 43 | F-82 | B. safensis F-82 | KT027733 |

| 44 | F-88 | O. kimchii F-88 | KT027739 |

| 45 | F-90 | E. mexicanum F-90 | KT027741 |

| 46 | F-91 | Exiguobacterium sp. F-91 | KT027742 |

| S. No. | Strains | l-tryptophan (µg mL−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 500 | ||

| Auxin (µg mL−1) | |||

| 1 | Gracilibacillus saliphilus F-1 | 6.20 (a) | 15.70 (a) |

| 2 | Staphylococcus petrasii F-2 | 9.30 (a) | 113.50 (o) |

| 3 | Virgibacillus salarius F-3 | 87.90 (i) | 150.00 (p) |

| 4 | Zhihengliuella flava F-9 | 44.70 (d–h) | 215.00 (r) |

| 5 | S. jettensis F-11 | 63.20 (g–i) | 185.70 (qr) |

| 6 | S. arlettae F-12 | 51.40 (e–i) | 174.30 (pq) |

| 7 | Exiguobacterium sp. F-41 | 6.40 (a) | 43.50 (a–f) |

| 8 | S. jettensis F-42 | 33.60 (d–g) | 78.70 (l–o) |

| 9 | Salinicoccus sesuvii F-43 | 16.50 (abc) | 28.40 (abc) |

| 10 | S. devriesei F-47 | 78.30 (hi) | 28.00 (abc) |

| 11 | Bacillus megaterium F-58 | 20.80 (abc) | 48.70 (a–g) |

| 12 | B. aryabhattai F-59 | 25.90 (d–g) | 61.20 (i–n) |

| 13 | S. warneri F-63 | 6.40 (a) | 14.00 (a) |

| 14 | Arthrobacter bergerei F-64 | 13.40 (ab) | 25.50 (abc) |

| 15 | A. ardleyensis F-65 | 9.10 (a) | 29.60 (abc) |

| 16 | S. arlettae F-69 | 14.30 (abc) | 54.20 (h–n) |

| 17 | S. cohnii F-70 | 15.70 (abc) | 42.10 (a–f) |

| 18 | S. arlettae F-71 | 53.60 (f–i) | 88.60 (no) |

| 19 | S. jettensis F-72 | 30.60 (d–g) | 59.80 (i–n) |

| 20 | Pseudomonas rhizosphaerae F-73 | 36.80 (d–g) | 67.70 (g–n) |

| 21 | S. gallinarum F-74 | 15.40 (abc) | 23.00 (abc) |

| 22 | S. pasteuri F-78 | 10.40 (a) | 36.90 (a–c) |

| 23 | S. jettensis F-79 | 5.70 (a) | 24.50 (abc) |

| 24 | S. equorum F-80 | 7.60 (a) | 32.20 (a–d) |

| 25 | Halomonas nanhaiensis F-81 | 21.10 (abc) | 83.30 (mno) |

| 26 | B. safensis F-82 | 9.50 (a) | 43.90 (a–f) |

| 27 | B. stratosphericus F-83 | 23.60 (def) | 72.70 (k–n) |

| 28 | B. pumilus F-84 | 7.90 (a) | 18.10 (ab) |

| 29 | B. pumilus F-85 | 32.60 (a–d) | 59.80 (i–n) |

| 30 | B. marisflavi F-86 | 22.60 (abc) | 38.60 (a–e) |

| Strains | Shoot Length (cm) | Root Length (cm) | Roots/Plant | Fresh Weight (g) | Dry Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 23 (a) | 13 (b) | 6.4 (de) | 4.6 (a) | 0.7 (ab) |

| F-9 | 28 (bcd) | 20 (cd) | 4.8 (a) | 5.3 (ab) | 0.9 (abc) |

| F-11 | 32 (defg) | 20 (cde) | 5.6 (abcd) | 6.8 (a–e) | 1.1 (bc) |

| F-12 | 34 (fgh) | 25 (f) | 6.2 (bcde) | 8.8 (ef) | 1.3 (c) |

| F-35 | 31 (c–g) | 21 (de) | 5.7 (abcd) | 5.7 (abc) | 0.8 (ab) |

| F-37 | 29 (cd) | 20 (cde) | 5.5 (abcd) | 10.2 (f) | 0.9 (abc) |

| F-58 | 33 (efgh) | 20 (cde) | 6.0 (bcd) | 7.4 (b–f) | 0.9 (abc) |

| F-71 | 34 (gh) | 22 (def) | 5.7 (abcd) | 8.1 (cdef) | 1.1 (bc) |

| F-72 | 37 (h) | 24 (f) | 7.1 (e) | 7.8 (b–f) | 1.0 (abc) |

| F-81 | 30 (cdef) | 20 (cd) | 5.0 (ab) | 7.5 (b–f) | 1.3 (c) |

| F-83 | 29 (cde) | 23 (ef) | 6.2 (cde) | 4.2 (a) | 0.6 (a) |

| F-84 | 31 (c–g) | 22 (def) | 5.1 (abc) | 6.0 (abcd) | 1 (abc) |

| F-87 | 28 (bc) | 19 (cd) | 5.4 (abcd) | 8.6 (def) | 1.1 (bc) |

| * C-1 | 22 (a) | 10 (a) | 5.6 (abcd) | 9.1 (ef) | 1.1 (bc) |

| * C-2 | 24 (ab) | 14 (b) | 6.5 (de) | 7.8 (b–f) | 1.3 (c) |

| * C-3 | 23 (a) | 17 (c) | 5.6 (abcd) | 10.1 (f) | 1.4 (ab) |

| Strains | NaCl (mM) | Shoot Length (cm) | Root Length (cm) | Roots/Plant | Fresh Weight (g) | Dry Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 22 (b–g) | 13 (abc) | 5.0 (jklm) | 0.9 (abcd) | 0.1 (a) |

| 200 | 22 (bcde) | 16 (bcde) | 4.2 (i–m) | 1.2 (c–j) | 0.1 (abcd) | |

| 400 | 14 (a) | 13 (abc) | 4.3 (a–e) | 1.1 (c–g) | 0.1 (ab) | |

| F-9 | 0 | 29 (i–o) | 19 (e–k) | 5.0 (b–j) | 2.0 (r) | 0.3 (e–l) |

| 200 | 29 (i–p) | 21 (g–n) | 5.2 (b–l) | 1.7 (pqr) | 0.2 (abcd) | |

| 400 | 25 (d–i) | 21 (f–m) | 4.6 (a–f) | 1.6 (l–q) | 0.2 (c–h) | |

| F-11 | 0 | 32 (n–s) | 20 (e–k) | 6.0 (e–l) | 1.8 (qr) | 0.4 (nop) |

| 200 | 35 (rs) | 25 (m) | 6.0 (f–l) | 1.6 (m–r) | 0.4 (op) | |

| 400 | 32 (n–r) | 24 (klmn) | 5.0 (b–k) | 1.6 (n–r) | 0.2 (e–j) | |

| F-12 | 0 | 34 (pqrs) | 25 (mn) | 6.2 (h–m) | 1.6 (n–r) | 0.3 (j–p) |

| 200 | 34 (pqrs) | 23 (j–n) | 6.0 (f–m) | 1.4 (g–n) | 0.3 (d–j) | |

| 400 | 30 (k–r) | 22 (h–n) | 6.3 (jklm) | 1.3 (f–l) | 0.3 (e–k) | |

| F-35 | 0 | 31 (l–r) | 21 (g–n) | 6.0 (f–l) | 1.5 (j–p) | 0.2 (c–h) |

| 200 | 26 (f–l) | 21 (g–n) | 6.4 (klm) | 1.2 (c–i) | 0.2 (c–g) | |

| 400 | 25 (e–i) | 21 (g–m) | 5.0 (b–j) | 1.0 (b–f) | 0.2 (e–j) | |

| F-37 | 0 | 29 (i–o) | 20 (f–l) | 5.5 (e–l) | 1.0 (a–e) | 0.4 (k–p) |

| 200 | 27 (g–m) | 21 (g–n) | 5.3 (b–l) | 0.7 (ab) | 0.1 (abc) | |

| 400 | 23 (b–g) | 16 (bcde) | 5.1 (b–k) | 1.4 (g–n) | 0.3 (i–o) | |

| F-58 | 0 | 33 (o–s) | 21 (f–m) | 6.0 (g–m) | 1.2 (d–k) | 0.3 (e–j) |

| 200 | 29 (i–o) | 21 (f–m) | 5.0 (b–i) | 1.7 (opqr) | 0.2 (c–i) | |

| 400 | 23 (b–g) | 21 (f–m) | 3.4 (a) | 1.1 (c–g) | 0.4 (l–p) | |

| F-71 | 0 | 34 (qrs) | 22 (h–n) | 6.0 (f–l) | 1.4 (h–p) | 0.3 (f–m) |

| 200 | 33 (o–s) | 23 (j–n) | 6.0 (g–m) | 1.5 (l–q) | 0.3 (e–k) | |

| 400 | 23 (c–h) | 18 (d–i) | 5.0 (b–i) | 1.5 (k–p) | 0.3 (g–m) | |

| F-72 | 0 | 37 (s) | 24 (lmn) | 7.1 (m) | 1.7 (opqr) | 0.3 (f–m) |

| 200 | 32 (n–r) | 18 (d–h) | 8.6 (n) | 1.6 (m–r) | 0.2 (c–h) | |

| 400 | 25 (e–i) | 21 (g–n) | 5.0 (b–h) | 1.3 (g–m) | 0.3 (i–o) | |

| F-81 | 0 | 30 (i–q) | 19 (e–j) | 5.0 (b–k) | 1.4 (i–p) | 0.4 (p) |

| 200 | 28 (i–o) | 20 (f–l) | 5.0 (b–g) | 1.5 (j–p) | 0.2 (bcde) | |

| 400 | 20 (bcd) | 16 (cdef) | 4.6 (a–g) | 1.0 (b–f) | 0.1 (abc) | |

| F-83 | 0 | 29 (i–o) | 23 (i–n) | 6.2 (i–m) | 1.0 (a–f) | 0.2 (c–g) |

| 200 | 29 (i–o) | 22 (g–n) | 5.5 (e–l) | 1.0 (abcd) | 0.2 (c–h) | |

| 400 | 21 (bcde) | 19 (e–k) | 4.6 (a–f) | 0.7 (a) | 0.2 (b–f) | |

| F-84 | 0 | 31 (m–r) | 22 (h–n) | 5.1 (b–k) | 1.1 (c–g) | 0.2 (d–j) |

| 200 | 28 (i–n) | 18 (d–h) | 5.0 (b–i) | 1.1 (c–g) | 0.2 (b–f) | |

| 400 | 20 (bcd) | 18 (d–h) | 4.1 (abcd) | 1.4 (g–o) | 0.3 (h–n) | |

| F-87 | 0 | 28 (i–n) | 19 (e–j) | 5.4 (d–l) | 1.2 (c–h) | 0.2 (d–j) |

| 200 | 32 (n–s) | 22 (g–n) | 6.0 (f–m) | 1.2 (e–l) | 0.3 (e–l) | |

| 400 | 28 (h–n) | 20 (f–l) | 5.0 (b–k) | 1.4 (g–n) | 0.3 (e–j) | |

| * C-1 | 0 | 22 (b–f) | 10 (a) | 6.0 (e–l) | 1.3 (f–l) | 0.2 (c–h) |

| 200 | 19 (bc) | 12 (ab) | 5.2 (b–l) | 1.4 (g–n) | 0.2 (b–f) | |

| 400 | 25 (e–i) | 18 (d–h) | 4.0 (ab) | 1.6 (m–r) | 0.4 (mnop) | |

| * C-2 | 0 | 24 (d–i) | 14 (abcd) | 6.5 (lm) | 1.4 (g–n) | 0.2 (c–h) |

| 200 | 19 (b) | 15 (bcde) | 5.4 (c–l) | 1.4 (g–n) | 0.2 (c–g) | |

| 400 | 26 (e–k) | 15 (bcde) | 4.6 (a–f) | 1.4 (g–o) | 0.2 (c–h) | |

| * C-3 | 0 | 23 (c–h) | 17 (defg) | 5.6 (e–l) | 1.1 (c–g) | 0.2 (abcd) |

| 200 | 22 (bcde) | 18 (d–h) | 4.6 (a–g) | 1.0 (abc) | 0.2 (c–g) | |

| 400 | 19 (bc) | 21 (f–m) | 4.0 (abc) | 1.2 (c–i) | 0.3 (i–o) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aslam, F.; Ali, B. Halotolerant Bacterial Diversity Associated with Suaeda fruticosa (L.) Forssk. Improved Growth of Maize under Salinity Stress. Agronomy 2018, 8, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8080131

Aslam F, Ali B. Halotolerant Bacterial Diversity Associated with Suaeda fruticosa (L.) Forssk. Improved Growth of Maize under Salinity Stress. Agronomy. 2018; 8(8):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8080131

Chicago/Turabian StyleAslam, Faiza, and Basharat Ali. 2018. "Halotolerant Bacterial Diversity Associated with Suaeda fruticosa (L.) Forssk. Improved Growth of Maize under Salinity Stress" Agronomy 8, no. 8: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8080131

APA StyleAslam, F., & Ali, B. (2018). Halotolerant Bacterial Diversity Associated with Suaeda fruticosa (L.) Forssk. Improved Growth of Maize under Salinity Stress. Agronomy, 8(8), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8080131