Development and Application of an LDR-Based SNP Panel for High-Resolution Genotyping and Variety Identification in Sugarcane

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Description of Samples

2.1.2. Genomic DNA Extraction

2.2. SLAF Sequencing and SNP Variant Comparison

2.2.1. Reference Genome Selection

2.2.2. Sequencing and Alignment

2.3. SNP Molecular Marker Development

2.3.1. High-Quality SNP Filtering

2.3.2. Multiple Marker Typing System

2.3.3. Multiple SNP Typing Kit

2.3.4. SNP Filtering and “Diploidization” Processing for the Polyploid Genome

2.4. Population Genetic Analysis

2.5. SNP Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. SLAF-seq and Reference Genome Comparison

3.2. High-Quality SNP Screening

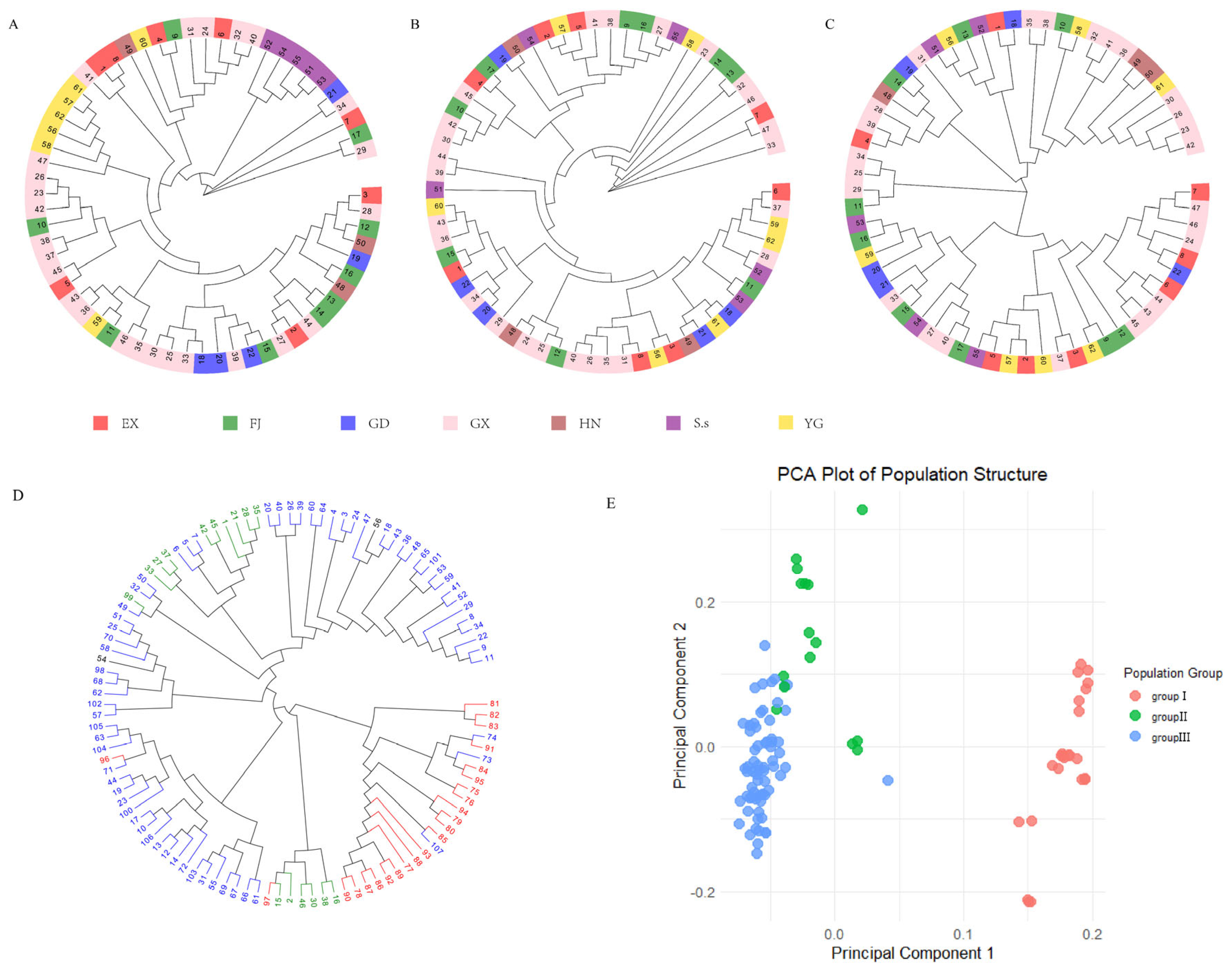

3.3. Population Genetic Diversity

3.4. SNP Marker Development

3.5. Variety Authenticity Testing

3.6. Performance Evaluation of the SNP Marker Panel

4. Discussion

4.1. Application and Challenges of SLAF-seq Technology in the Complex Sugarcane Genome

4.2. A “Diploidized” SNP Screening Strategy to Address Polyploid Challenges

4.3. Implications of Reference Genome Selection and Empirical Validation

4.4. Population Genetic Structure and Its Breeding Implications

4.5. Comparison of Molecular Marker Systems and Future Applications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xin, Y.; Tao, F. Optimizing genotype-environment-management interactions to enhance productivity and eco-efficiency for wheat-maize rotation in the North China Plain. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib-Ur-Rahman, M.; Ahmad, A.; Raza, A.; Hasnain, M.U.; Alharby, H.F.; Alzahrani, Y.M.; Bamagoos, A.A.; Hakeem, K.R.; Ahmad, S.; Nasim, W.; et al. Impact of climate change on agricultural production; Issues, challenges, and opportunities in Asia. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 925548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerkar, G.; Devarumath, S.; Purankar, M.; Kumar, A.; Valarmathi, R.; Devarumath, R.; Appunu, C. Advances in Crop Breeding Through Precision Genome Editing. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 880195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chang, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Chang, C. Construction of SNP fingerprint and population genetic analysis of honeysuckle germplasm resources in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1080691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlestkina, E.K.; Salina, E.A. SNP markers: Methods of analysis, ways of development, and comparison on an example of common wheat. Genetika 2006, 42, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippolis, A.; Hollebrands, B.; Acierno, V.; de Jong, C.; Pouvreau, L.; Paulo, J.; Gezan, S.A.; Trindade, L.M. GWAS Identifies SNP Markers and Candidate Genes for Off-Flavours and Protein Content in Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.). Plants 2025, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Martínez-Moncayo, C.; Lagos-Burbano, T.C. Genetic analysis of a potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) breeding collection for southern Colombia using Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) markers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selga, C.; Chrominski, P.; Carlson-Nilsson, U.; Andersson, M.; Chawade, A.; Ortiz, R. Diversity and population structure of Nordic potato cultivars and breeding clones. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, P.G.; Uitdewilligen, J.G.; Voorrips, R.E.; Visser, R.G.; van Eck, H.J. Development and analysis of a 20K SNP array for potato (Solanum tuberosum): An insight into the breeding history. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 2387–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chu, N.; Feng, N.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, H.; Deng, Z.; Shen, X.; Zheng, D. Global Responses of Autopolyploid Sugarcane Badila (Saccharum officinarum L.) to Drought Stress Based on Comparative Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garsmeur, O.; Droc, G.; Antonise, R.; Grimwood, J.; Potier, B.; Aitken, K.; Jenkins, J.; Martin, G.; Charron, C.; Hervouet, C.; et al. A mosaic monoploid reference sequence for the highly complex genome of sugarcane. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, A.L.; Garsmeur, O.; Lovell, J.T.; Shengquiang, S.; Sreedasyam, A.; Jenkins, J.; Plott, C.B.; Piperidis, N.; Pompidor, N.; Llaca, V.; et al. The complex polyploid genome architecture of sugarcane. Nature 2024, 628, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liu, H.; Ma, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, G. Genome-wide assessment of population structure and genetic diversity of Chinese Lou onion using specific length amplified fragment (SLAF) sequencing. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, M.; Sun, F.; Zhao, X.; He, M.; Li, T.; Lu, P.; Xu, Y. Genetic Divergence and Population Structure in Weedy and Cultivated Broomcorn Millets (Panicum miliaceum L.) Revealed by Specific-Locus Amplified Fragment Sequencing (SLAF-Seq). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 688444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashima, K.; Hosaka, F.; Terakami, S.; Kunihisa, M.; Nishitani, C.; Moromizato, C.; Takeuchi, M.; Shoda, M.; Tarora, K.; Urasaki, N.; et al. SSR markers developed using next-generation sequencing technology in pineapple, Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. Breed. Sci. 2020, 70, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.O.; Zhang, N.; Jin, H.; Si, H. Genetic Analysis of Potato Breeding Collection Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Markers. Plants 2023, 12, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Sinha, S.; Yadav, R.K. Medical and scientific writing: Time to go lean and mean. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2017, 8, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangwei, C.; Rongjian, T.; Fuan, N.; Jihua, Z.; Bin, S.; Zhongyong, L.; Can, C.; Liming, C. A New PCR/LDR-Based Multiplex Functional Molecular Marker for Marker-Assisted Breeding in Rice. Rice Sci. 2021, 28, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurn, J.D.; Rouse, M.N.; Chao, S.; Aoun, M.; Macharia, G.; Hiebert, C.W.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Bonman, J.M.; Acevedo, M. Dissection of the multigenic wheat stem rust resistance present in the Montenegrin spring wheat accession PI 362698. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Hua, X.; Ma, X.; Zhu, F.; Jones, T.; Zhu, X.; Bowers, J.; et al. Allele-defined genome of the autopolyploid sugarcane Saccharum spontaneum L. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1565–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lang, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Qu, H.; Pu, Z.; Yang, F.; Yu, M.; Feng, J. SNP loci identification and KASP marker development system for genetic diversity, population structure, and fingerprinting in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, Y.; Yang, P.; Cai, X.; Yang, L.; Ma, J.; Ou, Y.; Liu, T.; Ali, I.; Liu, D.; et al. A high density SLAF-seq SNP genetic map and QTL for seed size, oil and protein content in upland cotton. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; He, Y.; Iqbal, Y.; Shi, Y.; Huang, H.; Yi, Z. Investigation of genetic relationships within three Miscanthus species using SNP markers identified with SLAF-seq. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, E.; Battey, C.J. Minor allele frequency thresholds strongly affect population structure inference with genomic data sets. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2019, 19, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Sun, B.; Lei, J. Specific-Locus Amplified Fragment Sequencing (SLAF-Seq) as High-Throughput SNP Genotyping Methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2264, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerard, D.; Ferrão, L.F.V.; Garcia, A.A.F.; Stephens, M. Genotyping Polyploids from Messy Sequencing Data. Genetics 2018, 210, 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, Y.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Y.; et al. The highly allo-autopolyploid modern sugarcane genome and very recent allopolyploidization in Saccharum. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lyu, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Q.; Xie, T.; Li, H.; Chen, R.; Sun, D.; Yang, Y.; et al. Construction of an SNP fingerprinting database and population genetic analysis of 329 cauliflower cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.; Wei, Q.; Yan, Y.; Gan, D.; Bao, C.; et al. Construction of SNP fingerprints and genetic diversity analysis of radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1329890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Gao, M.; Wu, P.; Yan, J.; AbdelRahman, M.A.E. Image Classification of Wheat Rust Based on Ensemble Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolhuijzen, P.; Sanglard, L.; Paterson, D.J.; Gray, S.; Khambatta, K.; Hackett, M.J.; Zerihun, A.; Gibberd, M.R.; Naim, F. Spatiotemporal patterns of wheat response to Pyrenophora tritici-repentis in asymptomatic regions revealed by transcriptomic and X-ray fluorescence microscopy analyses. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 4707–4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, S.H.; Cockram, J.; Hickey, L.T. Insights into deployment of DNA markers in plant variety protection and registration. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 1911–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Huang, C.; Huang, G.; Xu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Development and Application of an LDR-Based SNP Panel for High-Resolution Genotyping and Variety Identification in Sugarcane. Agronomy 2026, 16, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030343

Zhao W, Wang Y, Yang Z, Zhao J, Huang C, Huang G, Xu L, Liu J, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, et al. Development and Application of an LDR-Based SNP Panel for High-Resolution Genotyping and Variety Identification in Sugarcane. Agronomy. 2026; 16(3):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030343

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Weitong, Yue Wang, Zhiwei Yang, Junjie Zhao, Chaohua Huang, Guoqiang Huang, Liangnian Xu, Jiayong Liu, Yong Zhao, Yuebin Zhang, and et al. 2026. "Development and Application of an LDR-Based SNP Panel for High-Resolution Genotyping and Variety Identification in Sugarcane" Agronomy 16, no. 3: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030343

APA StyleZhao, W., Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Zhao, J., Huang, C., Huang, G., Xu, L., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Deng, Z., & Zhao, X. (2026). Development and Application of an LDR-Based SNP Panel for High-Resolution Genotyping and Variety Identification in Sugarcane. Agronomy, 16(3), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy16030343