1. Introduction

Barley (

Hordeum vulgare L.) is the fourth most cultivated cereal globally and is classified into hulled barley and naked barley (qingke), based on grain threshing characteristics [

1,

2]. Due to its nutritional benefits, such as glycemic control, and its adaptability to high-altitude deserts and extreme climate conditions, barley serves as a vital staple in harsh environments which are unsuitable for wheat and other cereals [

3].

Starch synthases are on two major classes, based on their subcellular localization and association with starch granules: granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS) and soluble starch synthase (SS) [

4,

5]. While GBSS is primarily responsible for amylose synthesis, SS enzymes serve as the core catalytic components in amylopectin biosynthesis, facilitating both the elongation of glucan chains and the establishment of the branched architecture, characteristic of amylopectin [

6,

7]. The intricate process of amylopectin synthesis requires the coordinated action of SS with two additional enzymatic activities: starch branching enzymes (SBEs), which introduce α-1,6-glycosidic branch points, and starch debranching enzymes (SDBEs), which refine the branching pattern by removing misplaced branches [

8,

9,

10]. Higher plants possess four distinct classes of soluble starch synthases (SSI, SSII, SSIII, and SSIV), which exhibit both overlapping and specialized functions in starch biosynthesis [

11]. Among these, SSIII represents the largest isoform in terms of molecular weight, and is particularly important in determining amylopectin structure. Biochemical studies have demonstrated that SSIII preferentially elongates longer glucan chains (DP ≥ 30) during starch synthesis [

12,

13,

14]. Genetic evidence further supports this functional specialization, as mutations disrupting SSIIIa activity result in compensatory increases in SSI-mediated synthesis of short-chain amylopectin (DP 6–12) [

15,

16].

The biosynthesis of starch depends on the synergistic action of multiple enzymes, where multiple enzymes organize into functional complexes to enhance catalytic efficiency and substrate specificity [

17]. In maize (

Zea mays) endosperm, SSIII forms a stable complex with several other starch biosynthetic enzymes, including ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase, the first committed step in starch synthesis), SSIIa, and SBEII isoforms. This multi-enzyme complex physically links substrate production (AGPase) with chain elongation (SSIIa/SSIII) and branching (SBEIIa/b) activities, thereby optimizing the flux through the amylopectin biosynthetic pathway [

18,

19]. Recent research has revealed additional layers of regulation in these enzymatic complexes. A study by Wan Jianmin’s group identified the OsLESV-FLO6 protein complex in rice (

Oryza sativa) that serves as a scaffold to recruit SSIII and isoamylase 1 (ISA1) to starch granules, thereby spatially organizing the enzymes involved in amylopectin chain elongation and debranching [

20]. Similarly, in maize endosperm, a high-molecular-weight complex (>669 kDa) containing SSIII, SSIIa, SBEIIa and SBEIIb has been characterized, with SSIII serving as both a structural and regulatory component that influences total starch accumulation rates [

21,

22]. The formation of SSIII-containing multi-enzyme complexes appears to be an evolutionarily conserved feature of starch biosynthesis across cereal species [

23]. Advanced protein separation techniques, including gel permeation chromatography and co-immunoprecipitation, have identified two distinct complexes in rice endosperm: (1) a large (>700 kDa) complex containing SSIIa, SSIIIa, SSIVb, SBEI, SBEIIb and pullulanase (PUL), and (2) a smaller (200–400 kDa) complex comprising SSI, SSIIa, SBEIIb, ISA1, PUL and plastidial starch phosphorylase 1 (PHO1) [

24,

25,

26]. These findings suggest a sophisticated partitioning of enzymatic activities between different complexes that may allow for fine-tuning of amylopectin structure under varying physiological conditions. The emerging picture from these studies reveals that starch synthases, particularly SSIII isoforms, could be important in determining both the quantity and quality of starch in major cereal crops, including barley. The formation of dynamic protein complexes might allow for precise coordination between substrate supply, chain elongation and branching activities. A deeper understanding of the functions and regulatory mechanisms of these two enzymes is significant for improving the quality and yield of crop starch. The current study provides important foundational knowledge for understanding how the barley SSIII isoforms (HvSSIIIa and HvSSIIIb) participate in these regulatory networks to control amylopectin synthesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioinformatics Analysis of HvSSIIIa, HvSSIIIb

Multiple sequence alignment of HvSSIIIa and HvSSIIIb homologs was conducted using ClustalX 2.0 with default parameters. The ClustalX comparison file was placed in MEGA 5.1 for phylogenetic tree visualization. GSDS2.0 (

https://gsds.gao-lab.org/Gsds_help.php, accessed on 22 September 2022) was used for structural visualization of HvSSIIIa, HvSSIIIb homolog genes. MEME5.5.8 (

https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme, accessed on 4 October 2022) was used to predict protein conserved domain, with 10 motifs set for search, and the results were visualized using TBtools4.4.5. Interpro89.0 (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro, accessed on 17 October 2022) was used to predict protein conservation domains, and the results were visualized using IBS. 2.0 (

https://ibs.renlab.org/, accessed on 26 October 2022) (September 2022–November 2022).

2.2. Construction of pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N and pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N Expression Vectors

RNA was extracted from “Tongmen Xika Bai”, as the material and reverse transcribed into cDNA as the template. Primers F: 5′-ATGGAGATGGCTCTCCGGCCA-3′ and R: 5′-TCAGAATTTTCGAGCGGCATGATA-3′ were designed using the designed HvSSIIIa gene sequence. The HvSSIIIb gene sequence was designed with primers F: 5′-ATGGAGATGGCTCTCCGGGCGCAG-3′ and R: 5′-TCAGTTCTTGCGCGCGGAATGGTA-3′ for PCR reaction (the annealing temperature in the PCR reaction is 69 °C). The purified DNA fragments were purified using the gel extraction kit (Cwbio, Nanjing, China), ligated into the pMD19-T vector (Takara Bio Inc., Beijing, China), and transferred into E. coli DH5α for colony PCR screening of monoclones. The positive clonal plasmids were selected and sent to Chengdu Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China) for sequencing. The translated amino acid sequences were compared with the GenBank NCBI 266.0 (BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) database using BLAST (December 2022–January 2023).

HvSSIIIa, using vector linear primer F: 5′-ttccaggggcccctgggatccATGGAGATGGCTCTCCGGC-3′ and R: 5′-ctcgagtcgacccgggaattcTCAGAATTTTCGAGCGGCA-3′, HvSSIIIb, using vector linear primer F: 5′-ttgtcgacggagctcgaattcATGGAGATGGCTCTCCGGG-3′ and R: 5′-gccatggctgatatcggatccTCAGTTCTTGCGCGCGGA-3′ for PCR reaction (the annealing temperature in the PCR reaction is 69 °C); the digestion sites of BamHI and EcoRI were added. The amplified fragments were attached to the expression vector, and the positive transformed colonies were screened by the PCR method. The positive clone recombinant plasmids were sent to Chengdu Qing Ke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China) for sequencing verification. The results indicated that the expression vectors of pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N and pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N were successfully constructed. Recombinant plasmids were isolated from the conjugations using the Fast Pure Plasmid Mini Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The expression plasmid vectors were transferred into E. coli BL21 (DE3) Rosetta, and the recombinant HvSSIIIa and HvSSIIIb fusion proteins were prepared using the selected transformation vectors (February 2023–April 2023).

2.3. Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted from the roots, stems, leaves and grains at different stages of barley “Tongmen Xika Bai”, using the total RNA extraction kit (Cwbio, Nanjing, China). Reverse transcription reactions were carried out using reverse transcription kits (Cwbio, Nanjing, China). Specific primers were designed on Primer 5.0 software. HvSSIIIa gene sequence design primer F: 5′-GTTCCACCGGATGCCTAT-3′, R: 5′-FRCCGAGACCTCCAACCTTT-3′. The HvSSIIIb gene sequence was designed with primers F: 5′-ATTCTGCCCTGGAGTTTC-3′ and R: 5′-GCTTTGCCGATGTGATGT-3′ for qPCR reaction. The experimental reaction system was 10 μL: TB Green Premix Ex Taq™ II (2×) 5 μL (Tli TaKaRa, Beijing, China), upstream primers 0.5 μL, downstream primers 0.5 μL, cDNA template (diluted 10 times) 1 μL RNase-free H2O 3μL. Reaction was carried out using the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The reaction parameters were as follows: ① Pre-denaturation: 95 °C for 2 min; ② PCR cycles 40 times: 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 20 s; and ③ Melting curve analysis: 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 15 s. Three technical replicates were set for each sample, and an internal reference gene β-actin control was also set. After the reaction was completed, the Ct values were derived. Outliers (repetitions with a standard deviation greater than 0.5) were eliminated, and the average value was taken as the Ct value of the sample. The relative expression level of the target gene was calculated by the 22−ΔΔCt method, using stably expressed internal reference genes (February 2023–March 2023).

2.4. Preparation and Purification of Recombinant HvSSIIIa, HvSSIIIb Fusion Protein

E. coli Rosetta carrying the pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N recombinant plasmid was cultured in 0.1 L LB (Luria–Bertani) medium containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin. The E. coli Rosetta transformants carrying the pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N recombinant plasmid were cultured in a medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin (Kan). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 8 h in an orbital shaker (150 rpm). After adding 0.5 mM IPTG, induction was performed at 28 °C for 6 h (150 rpm). Samples were taken every 2 h, and bacterial cells were collected at 4200 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The cells were resuspended in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and ultrasonically extracted to isolate the recombinant protein. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C to separate the soluble protein. The total extract, soluble fraction, and insoluble fraction were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining, for observation.

The E. coli Rosetta transformation was cultured overnight at 28 °C in 0.1 L of LB medium containing 50 µg/mL ampicillin/carbenicillin and 50 µg/mL IPTG. This resulted in the recombinant pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N and pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N fusion proteins. The recombinant fusion proteins were purified using the Biocytin HIS-tag/GST-tag protein purification kit, and the ultrasonic parameter power was 200 W. The intermittent ultrasonic method was adopted, with 5 s of ultrasonic treatment followed by 5 s of pause, for a total of 10 min. The eluted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE for further purification. The target protein bands were recovered from the gel through electrophoresis (May 2023–July 2023).

For antibody production, 500 µg of purified recombinant proteins (pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N and pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N) were emulsified with 500 µL of complete Freund’s adjuvant (1:1 v/v), and administered subcutaneously to New Zealand white rabbits (2 kg body weight). Procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan Agricultural University (no DKY-S20230605, Chengdu, China). The rabbits used in the experiment were housed in the Breeding Room located on the 7th Floor of Building 3, College of Agronomy, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu, China, under a separate cage-rearing mode. The indoor environment was strictly controlled, with temperature maintained at 18–22 °C. Daily management included cleaning up excrement in the cages, replacing contaminated bedding, and providing fresh water and rabbit food for the rabbits. For the immunization procedure, primary subcutaneous immunization was performed first, followed by five booster subcutaneous injections at 2-week intervals. Each injection contained 500 µg of antigen emulsified with 500 µL of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, at a volume ratio of 1:19. During the subcutaneous immunization and subsequent subcutaneous injections, the area with thicker subcutaneous fat on the rabbit’s back was selected as the injection site, and the drug solution was injected slowly. After each injection, close attention was paid to checking for bleeding or swelling at the puncture site, as well as monitoring whether the rabbits could move normally and eat and drink, to ensure their health status. Three days post-final immunization, blood was collected carefully, to maintain stability (without shaking), and allowed to clot overnight at room temperature, in darkness. Serum was separated by centrifugation (3000× g, 10 min, 4 °C) and mixed with glycerol (1:1 v/v) for cryopreservation at −80 °C. Antibody titers were determined by immunoblotting against the recombinant antigens (August 2023–October 2023).

2.5. Western Blot Detects the Sensitivity and Specificity of Anti-Recombinant Protein Polyclonal Serum

To analyze protein expression, total protein was extracted from developing grains of barley (Hordeum vulgare L. cv. ’Tongmen Xika Bai’). Protein samples (25 μg) were mixed with 5× SDS-PAGE loading buffer at a 1:4 ratio and denatured by boiling at 95 °C for 5 min. The denatured proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis at 100 V constant voltage, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining for 2 h and destaining for 1 h, to verify equal loading. Protein concentration was quantified using the Bradford protein assay (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). For immunoblotting, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane at 100 V, for 90 min. The membrane was blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for 1 h, at room temperature. Primary antibody incubation was performed overnight at 4 °C, using polyclonal antisera against HvSSIIIa or HvSSIIIb diluted 1:400 in blocking buffer. After three washes with TBST (TBS containing 0.5% Tween-20), the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Beyotime; 1:10,000 dilution) for 1 h, at room temperature. Following three additional TBST washes, protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit (Beyotime). To verify antibody specificity, identical procedures were performed using protein extracts from Escherichia coli expressing recombinant HvSSIIIa or HvSSIIIb. This comprehensive approach ensured specific detection of target proteins while confirming the absence of cross-reactivity with other barley proteins (November 2023–December 2023).

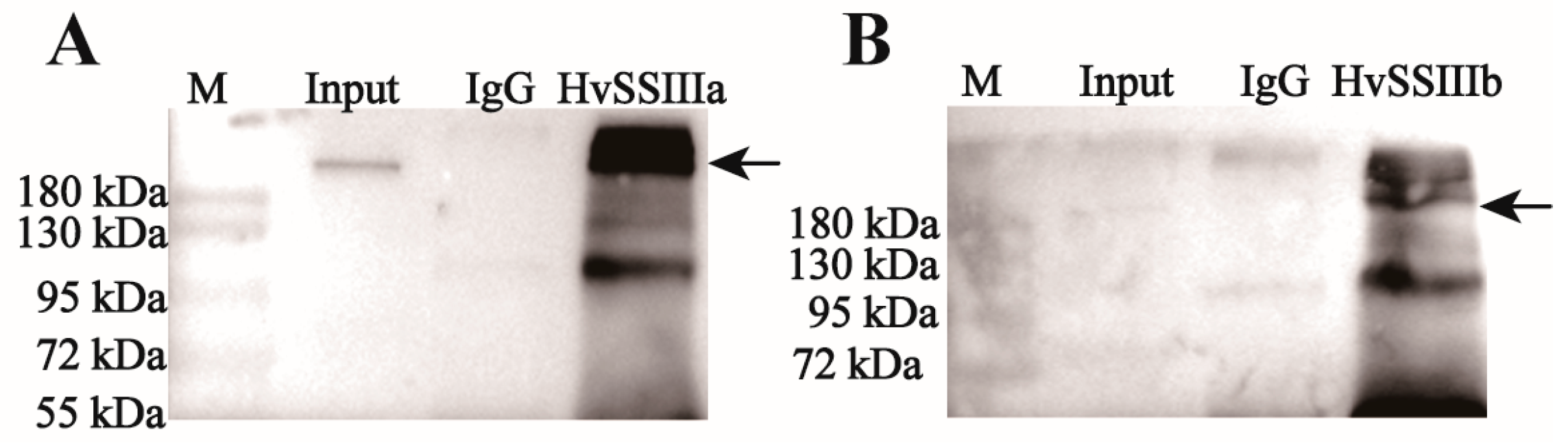

2.6. Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Barley seeds (0.1 g) were collected 25 days after pollination, and ground in liquid nitrogen; 1 mL of cell lysis buffer was added, to extract total protein. The extracted total protein was divided into two parts; one part was used as input, and the remaining sample was subjected to immunoprecipitation using Protein A+G Agarose (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The loading volume of the input was 5% of the total protein. Both the experimental group and the control group were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Co-IP agarose beads were sent to Shenzhen Micro Nano Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China) for proteomics analysis, based on nano-liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC-MS/MS). The criterion was that the candidate proteins should be specifically present in the IP group and have an abundance more than 1.5 times that of the IgG group. Based on the existing literature on starch synthesis, we screened the interacting proteins (January 2024–March 2024).

2.7. Validation of Interacting Proteins

Based on the published

HvSSIIIa and

HvSSIIIb gene sequences (NCBI accession numbers:

HvSSIIIa: XP_044965135.1,

HvSSIIIb: XP_044967973.1), specific primers for yeast two-hybrid experiments were designed using Novogene’s online primer design tool (

Table S1). PCR amplification was performed using bacterial cultures of positive clones as DNA templates, with all primers synthesized by Chengdu Barley Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). The amplified products were purified and subsequently recombined using the Aibotek 2× MultiF Seamless Assembly Mix (Aidlab Biotechnologies, Beijing, China) through a 10 min incubation at 50 °C, followed by immediate cooling at 4 °C. The recombinant products were then transformed into competent

E. coli DH5α cells for positive clone selection, followed by plasmid extraction using standard alkaline lysis methods.

For yeast transformation, a single colony of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 was inoculated from a YPDA (Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose Adenine) plate into 20 mL of liquid YPDA medium and grown overnight at 28 °C, with 200 rpm shaking. Five milliliters of this culture was then transferred to 50 mL fresh YPDA medium in a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask and incubated under the same conditions until reaching mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.5). The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000× g for 2 min at room temperature, washed twice with 0.1 M lithium acetate (LiAc), and finally resuspended in an appropriate volume of 0.1 M LiAc, to prepare competent cells. The transformation mixture was prepared in sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes containing 600 μL of 50% PEG3350 (w/v), 110 μL of 1× LiAc (0.1 M), 2 μg of each plasmid DNA (pGBKT7 and pGADT7 constructs), and 10 μL of denatured salmon sperm DNA (10 mg/mL) as carrier DNA.

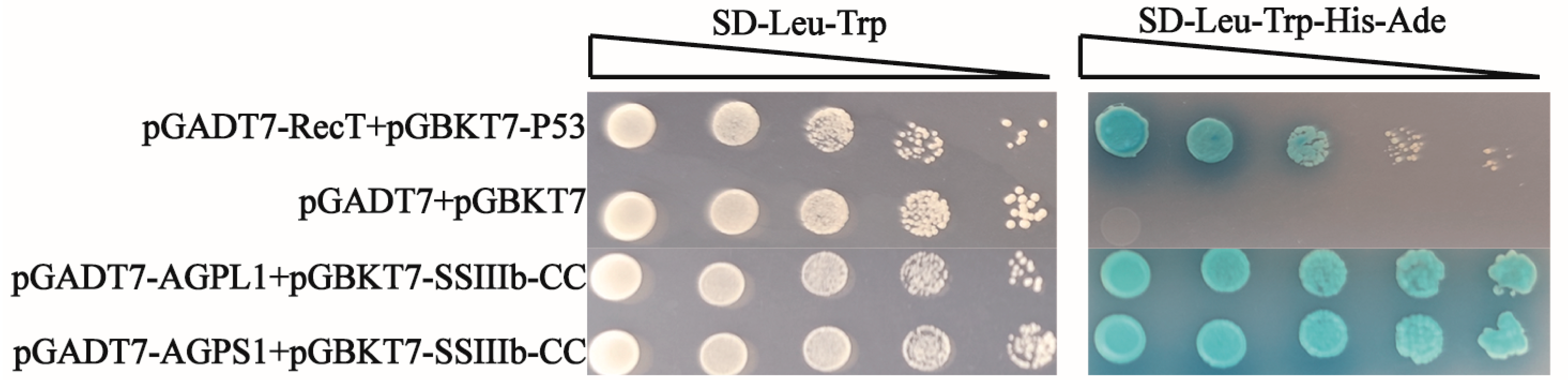

The recombinant plasmids (pGBKT7 and pGADT7 derivatives) were co-transformed into the freshly prepared yeast competent cells using the lithium acetate/polyethylene glycol method. The coiled-coil domains (CC) of both starch synthases were cloned into pGBKT7 (bait vectors: pGBKT7-HvSSIIIa-CC [400–800 aa] and pGBKT7-HvSSIIIb-CC [800–1200 aa]), while AGPase subunits were inserted into pGADT7 (pGADT7-HvAGPL1 and pGADT7-HvAGPS1). Following transformation, cells were plated on appropriate selection media (-Leu/-Trp) and incubated at 28 °C for 3–5 days. Protein–protein interactions were assessed by growth on quadruple-dropout media (-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp) and through α-galactosidase activity assays, using X-α-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-D-galactopyranoside) as substrate. The development of blue coloration within 8–24 h indicated positive protein interactions, while white colonies served as negative controls (May 2024–July 2024).

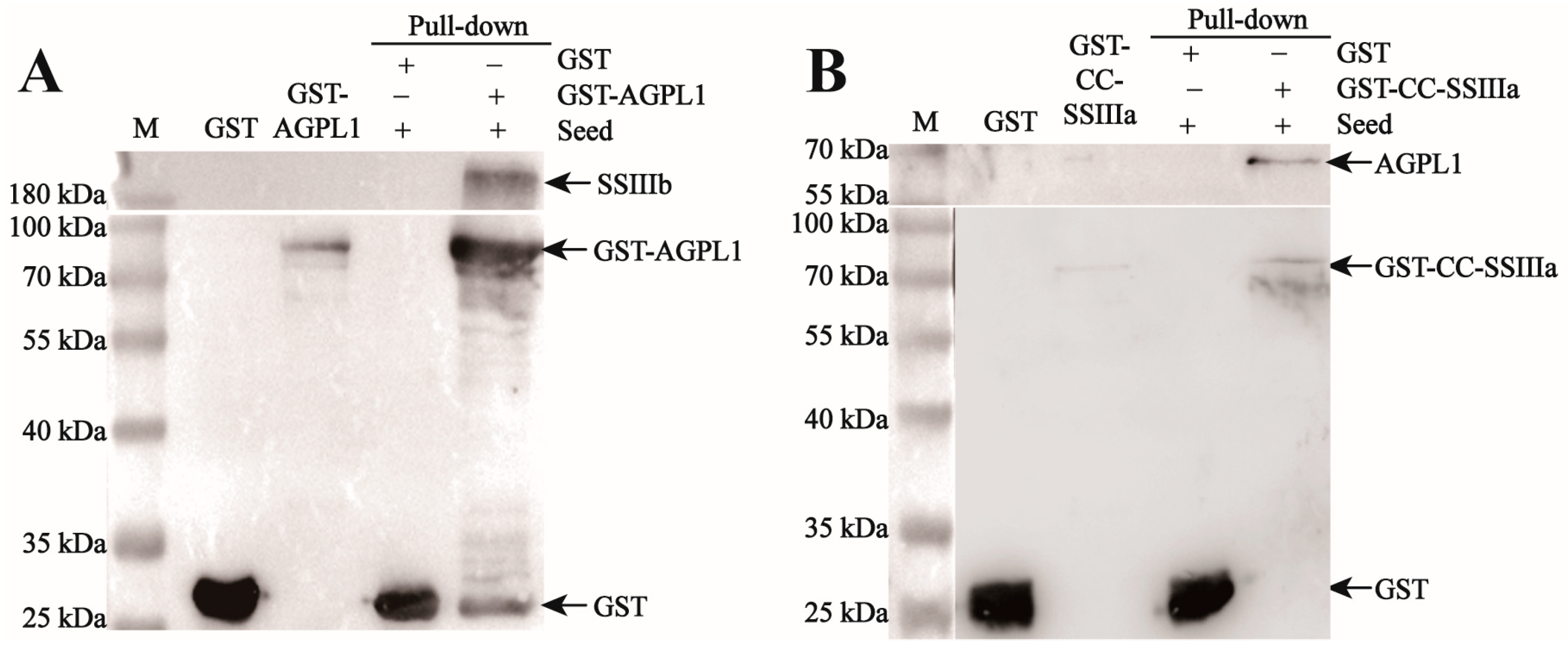

2.8. GST Pull-Down Assay for Protein Interaction Validations

The purified 1 mg GST-tagged fusion protein (including GST-tagged protein, GST-HVAGPL1, and GST-CC-HVSSIIIA) was incubated in a rotating solution at 10 μL GST Agarose Beads, at 4 °C, for 4 h, followed by overnight incubation with the supernatant from seed lysis. The mixture was then subjected to 800 r/min 4 °C centrifugation for 2 min, with the supernatant discarded. It was washed with 200 μL of PBS and centrifuged again for 2 min, with the supernatant removed, and this process was repeated five times. After washing, 40 μL PBS of Agarose Beads was added to resuspend the protein, followed by the addition of 10 μL of 5×Protein Loading buffer. The mixture was boiled for 1 min, and the protein was then subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, the interacting proteins were detected by Western blot: after membrane transfer, the PVDF membrane was sealed with 10% skimmed milk powder for 2 h, and then the primary antibody (HIS-HvAGPL1, diluted at 1:500) was added and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing TBST three times, we added HRP-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h (diluted at 1:20,000); after re-washing, the signal was detected by developing with the ECL chemiluminescence kit (August 2024–November 2024).

4. Discussion

This study successfully developed high-specificity polyclonal antibodies against barley starch synthase III isoforms (HvSSIIIa and HvSSIIIb), through an optimized prokaryotic expression and immunization protocol. The strategic selection of

E. coli as an expression host provided multiple advantages, including well-characterized genetics, high transformation efficiency, and cost-effective cultivation requirements [

27]. Through meticulous RT-PCR amplification, cloning, and homologous recombination, we constructed two prokaryotic expression vectors (pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N and pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N) that enabled high-yield production of GST-tagged recombinant proteins. The fusion tags significantly enhanced protein solubility and purification efficiency, while maintaining structural integrity, allowing for large-scale antigen production [

28]. Antibody specificity was rigorously validated through Western blot analysis, demonstrating the capacity to detect endogenous HvSSIII isoforms at working dilutions up to 1:500 [

11]. The dilution series experiments revealed excellent antibody titer, with consistent signal detection even at low antigen concentrations, confirming their suitability for both qualitative and quantitative applications.

Our findings substantially expand current understanding of SSIII functionality in cereal crops. Beyond its established enzymatic role in glucan chain elongation, we demonstrate that SSIII serves as a critical regulatory node in starch biosynthesis through extensive protein–protein interactions. This dual functionality aligns with emerging evidence from maize studies showing SSIII’s capacity to modulate the activity of other starch biosynthetic enzymes through physical associations. The CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of SSIIIa in barley resulted in significant alterations in resistant starch content [

29], strongly suggesting that these interaction networks directly influence starch quality parameters. Through comprehensive co-immunoprecipitation coupled with mass spectrometry, we took the IgG group as the control, and screened the interacting proteins of soluble starch synthase through immunoprecipitation technology. A total of 44 proteins are mainly involved in the basic processes of starch synthesis, such as the ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase subunits (HvAGPL1 and HvAGPS1). As key rate-limiting enzymes in starch synthesis, they interact with SSIII to jointly regulate the supply of ADP-glucose precursors. Subsequently, these associations were verified through yeast two-hybrid and GST pull-down tests; the differential proteins, on the other hand, demonstrate functional differentiation. The specific proteins of SSIIIa are involved in processes such as hormone regulation (like the DELLA protein SLR1-like), while the 117 specific proteins of SSIIIb are mostly related to metabolism (such as the 14-3-3 protein), each playing a unique role in the regulatory network of starch synthesis. Among these interacting proteins, the research on AGPase is relatively abundant. Xu Guohua’s team’s study on OsAGPL1 and OsAGPS1 found that they are located in chloroplasts, catalyze the rate-limiting step of starch synthesis, and that their expression is induced by nitrogen- and phosphorus-deficiency stress [

30]. The 14-3-3 protein family is involved in the regulation of various cellular processes, such as signal transduction and metabolic-enzyme activity regulation, etc. [

31]. It may affect the starch synthesis process by interacting with SSIIIb, regulating the activity of enzymes related to starch synthesis or participating in the signal transduction pathways of starch synthesis. The function of the DELLA protein SLR1 has also been clarified. As a negative regulatory factor of gibberellin signal transduction, it may affect the growth and development of plants and hormone signal transduction, with indirect regulation of the expression of genes related to starch synthesis and the activity of enzymes [

32]. Recent studies have also found that SUMOylation modification at specific sites can enhance the salt tolerance and yield of rice, under stress [

33]. In this study, yeast two-hybrid and GST-Pulldown, as common techniques for verifying protein interactions in vitro, have certain limitations. Both rely on artificially constructed expression systems and lack the complex physiological environment in vivo, which may lead to the interactions detected in vitro not fully reflecting the real situation in vivo. However, these two methods can achieve mutual verification of results through complementary principles. Yeast two-hybrid is based on transcriptional activation to verify interaction, and GST-Pulldown is based on affinity-binding detection. The combined use of the two can reduce the possibility of false positives. Meanwhile, the Co-IP experiment adopted in this study is based on the interaction of endogenous proteins under physiological conditions, which can more truly reflect the protein binding situation under in vivo conditions. The combination of the three provides a more comprehensive chain of evidence for the verification of protein interactions.

The composition and regulation of starch biosynthetic complexes represents an area of growing research interest. While previous studies in maize and rice have identified multi-enzyme complexes containing SSIII, SBE, ISA, PUL and PHO [

34], our work provides the first detailed characterization of such complexes in barley. Particularly noteworthy is our discovery of potential phosphorylation-mediated regulation of complex assembly, evidenced by the identification of 14-3-3 proteins as interaction partners. This finding suggests a sophisticated regulatory mechanism where kinase signaling pathways may directly influence starch biosynthesis through post-translational modification of SSIII isoforms. The presence of conserved 14-3-3 binding motifs in HvSSIII sequences implies an evolutionarily conserved regulatory mechanism that may modulate enzyme activity through conformational changes, similar to the well-documented phosphorylation control of AGPase [

35,

36]. Phosphorylation of SS can regulate its activity and interaction with other proteins involved in starch synthesis. Changes in protein activity typically require the interaction between phosphorylated proteins and adapter 14-3-3 protein. The removal or reduction of phosphate groups in immunoprecipitation and Western blot experiments, which reduces or eliminates the immunoprecipitation signal, confirms that the SSIII protein in corn binds to the 14-3-3 protein [

37,

38,

39]. In

Arabidopsis thaliana, the SSIII gene family is a potential target for the 14-3-3 protein. Studies have found that the amino acid sequence of the SSIII family contains binding domain sequences corresponding to the 14-3-3 protein, suggesting that the 14-3-3 protein may regulate starch synthesis through interaction with SSIII [

38].

Several lines of evidence support the biological significance of these interactions. First, the tissue-specific expression patterns of HvSSIII isoforms correlate with known starch-accumulation profiles, suggesting functional specialization. Second, the identification of interaction domains provides mechanistic insights into complex formation. Third, the phosphorylation-dependent nature of some interactions offers potential explanations for the dynamic regulation of starch synthesis during grain development. These findings collectively advance our understanding of barley starch biosynthesis from a simple linear pathway to a sophisticated, regulated network of protein interactions and post-translational modifications.

5. Conclusions

The biosynthesis of starch in barley grains represents a sophisticated metabolic process involving coordinated action among multiple enzymatic components. Our study provides significant mechanistic insights into this process through comprehensive characterization of two key SSIII isoforms, HvSSIIIa and HvSSIIIb. We successfully established an efficient pipeline for antibody production by constructing prokaryotic expression vectors (pGEX-6p-1-HvSSIIIa-N and pET-30a-HvSSIIIb-N) and generating high-affinity rabbit polyclonal antibodies against these enzymes. These immunological tools demonstrated exceptional specificity and sensitivity in detecting endogenous HvSSIII proteins across various barley tissues, with reliable detection at dilutions up to 1:20,000. Through co-immunoprecipitation coupled with mass spectrometry, we systematically identified and validated protein interaction networks centered on HvSSIIIa and HvSSIIIb. Our findings reveal that these starch synthases form functional complexes with critical metabolic enzymes, including ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase subunits (HvAGPL1 and HvAGPS1), suggesting a previously unrecognized mechanism for coordinating substrate supply with chain elongation. The discovery of 14-3-3 proteins as potential regulatory partners further indicates that post-translational modifications may dynamically control starch biosynthetic complex assembly and activity.

These results substantially advance our understanding of barley starch biosynthesis in three key aspects: (1) by demonstrating the scaffold function of SSIII isoforms beyond their catalytic activity, (2) by revealing isoform-specific interaction profiles that suggest functional specialization, and (3) by identifying phosphorylation as a potential regulatory switch for complex formation. The methodological framework established in this study, combining advanced protein biochemistry with immunological tools, provides a robust platform for future investigations of cereal starch biosynthesis. Overall, the findings of this study offer a new perspective for understanding the molecular mechanism of starch synthesis in barely. By targeting and regulating the interaction between SIII and key interacting proteins, the starch content and quality of crops can be optimized, providing a theoretical basis and candidate targets for breeding high-starch crops.