Evaluation of Chemical Weed-Control Strategies for Common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) and Sweet White Lupine (Lupinus albus L.) Under Field Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site, Plant Materials, and Experimental Design

2.2. Herbicide Treatments Applied

2.3. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

2.4. Visual Assessment of Phytotoxicity

2.5. Plant Height

2.6. Weed Counts

2.7. Harvesting and Crop Cleaning Process

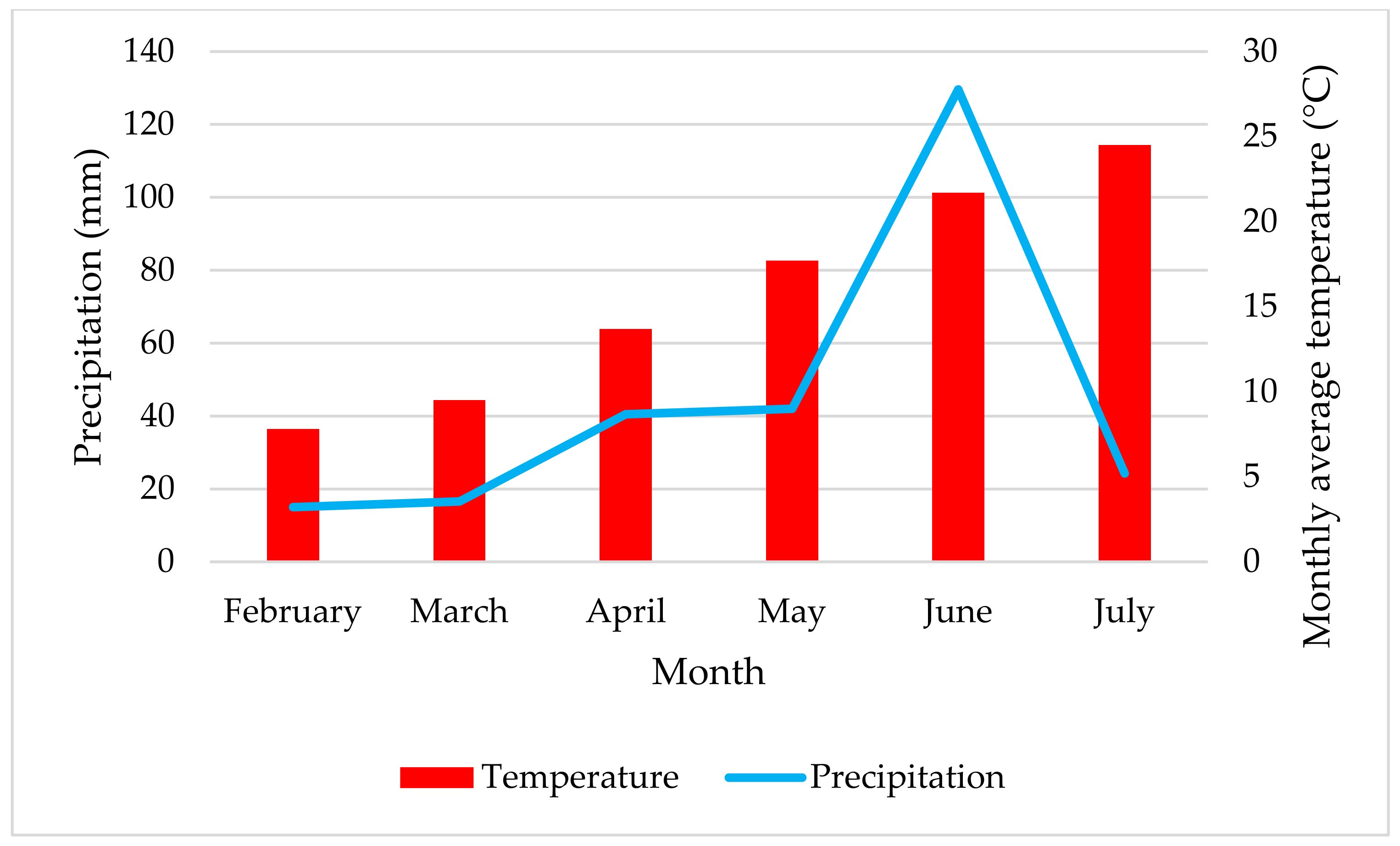

2.8. Precipitation and Average Monthly Temperature for the Growing Seasons

2.9. Statistical Analyses of Data Collected

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Treatments on Common Vetch in the First-Year Experiment (2023)

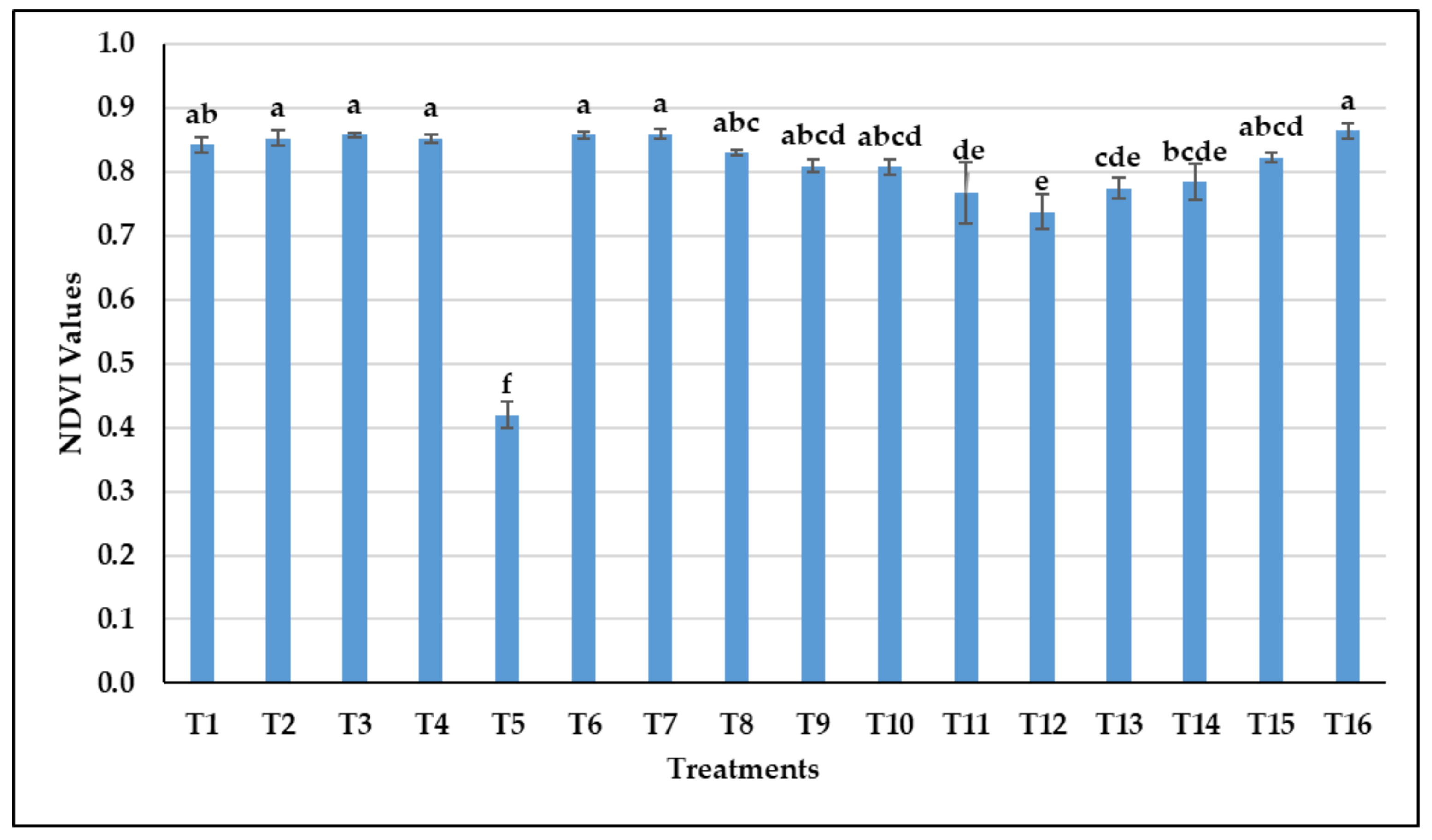

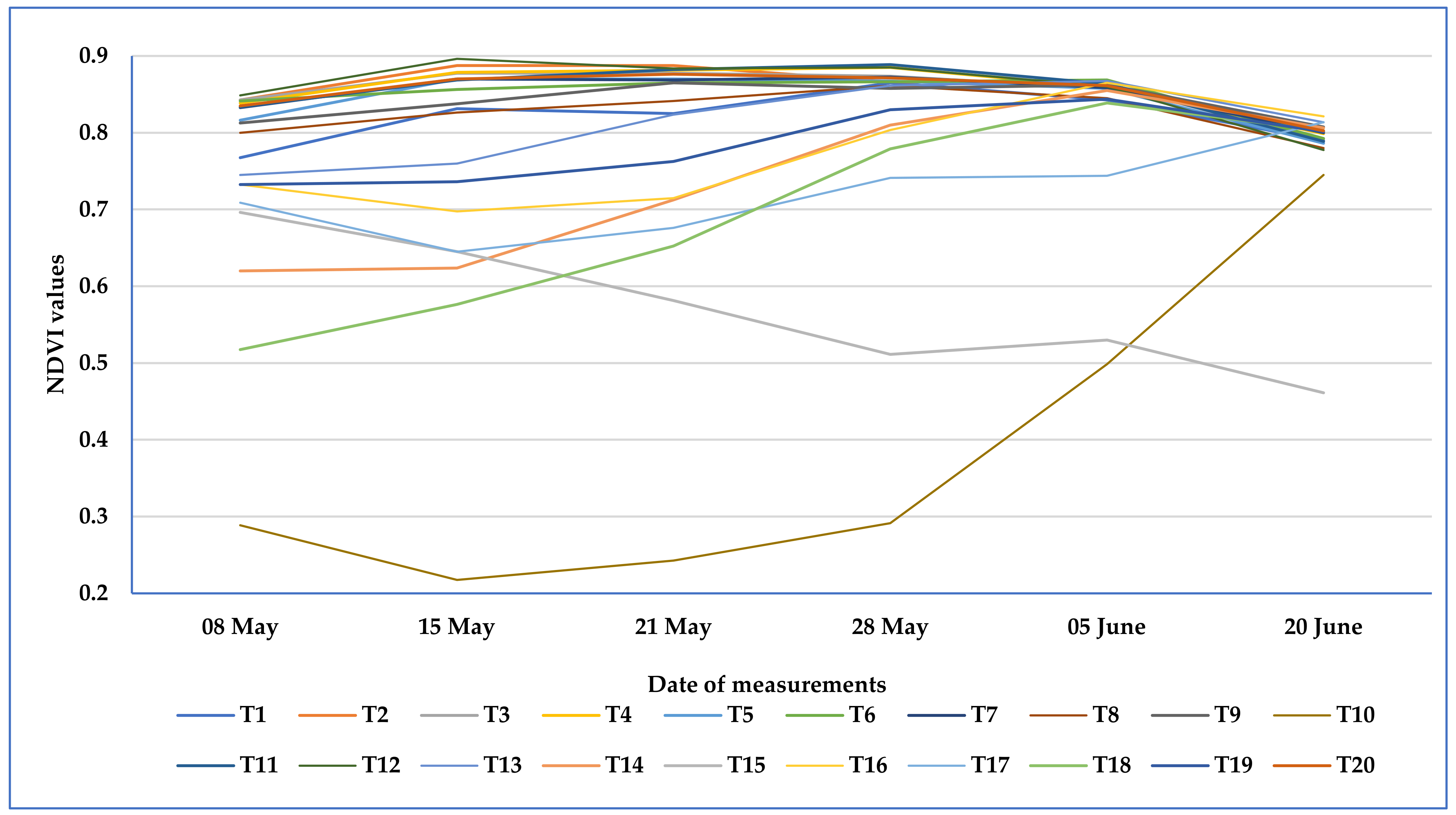

3.1.1. The Effect of Treatments on the NDVI Values of Common Vetch

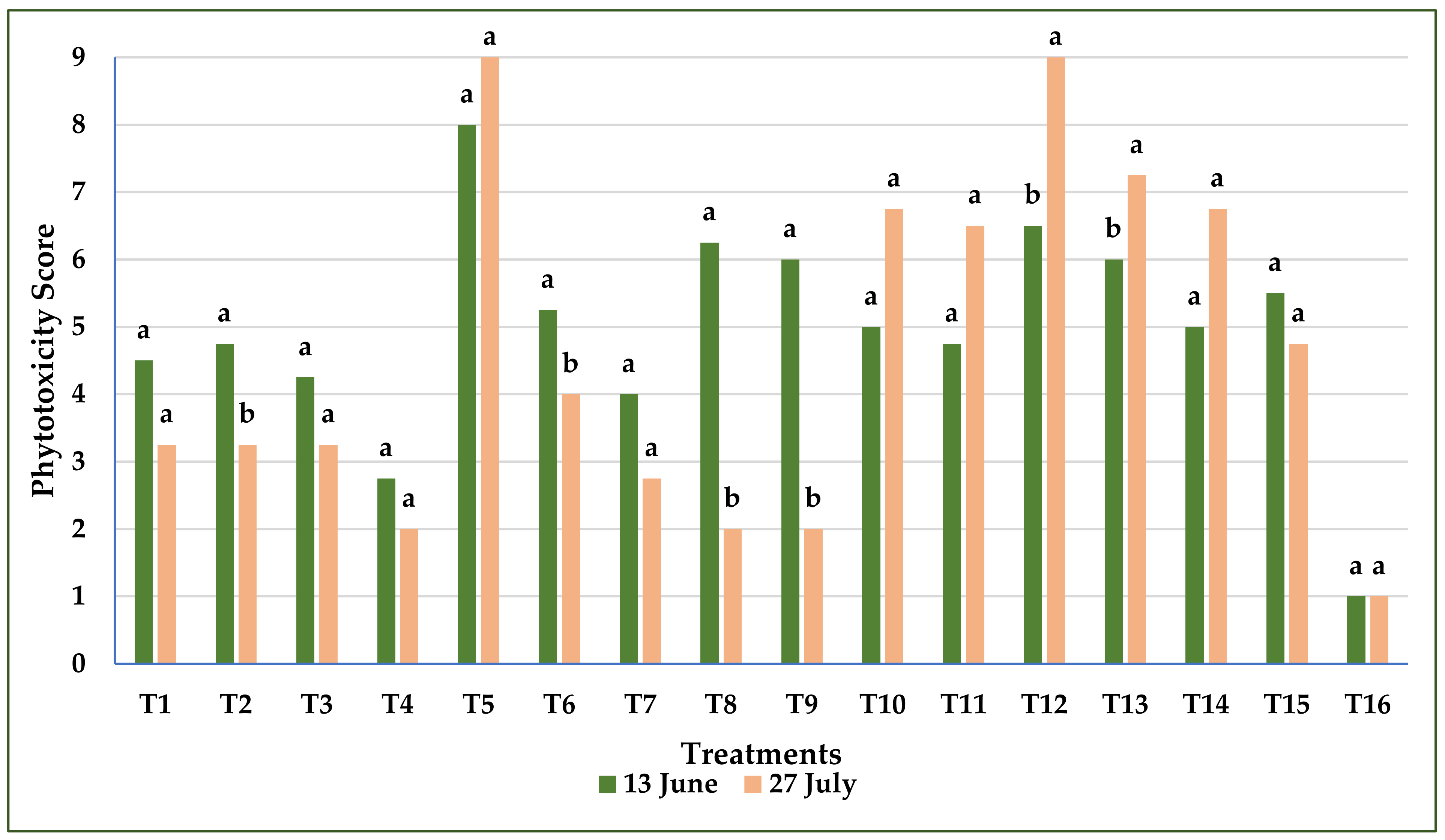

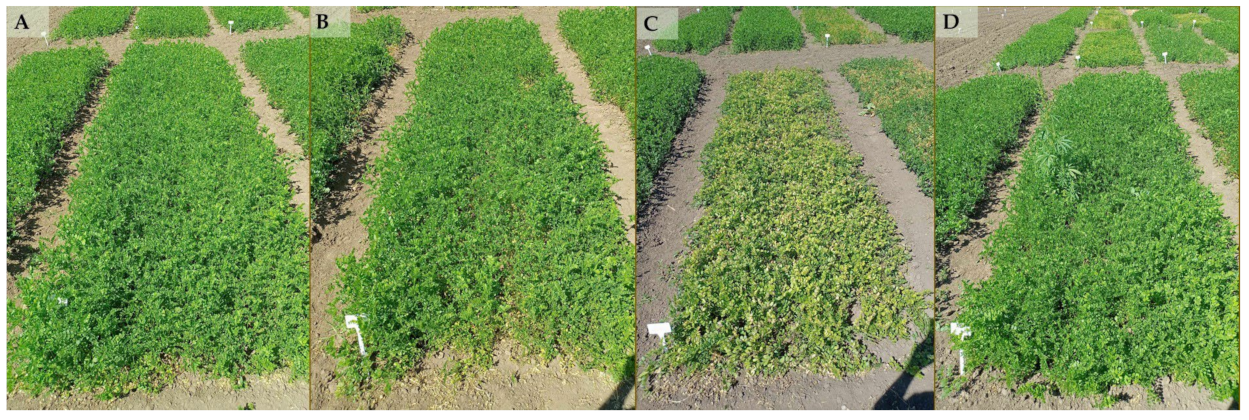

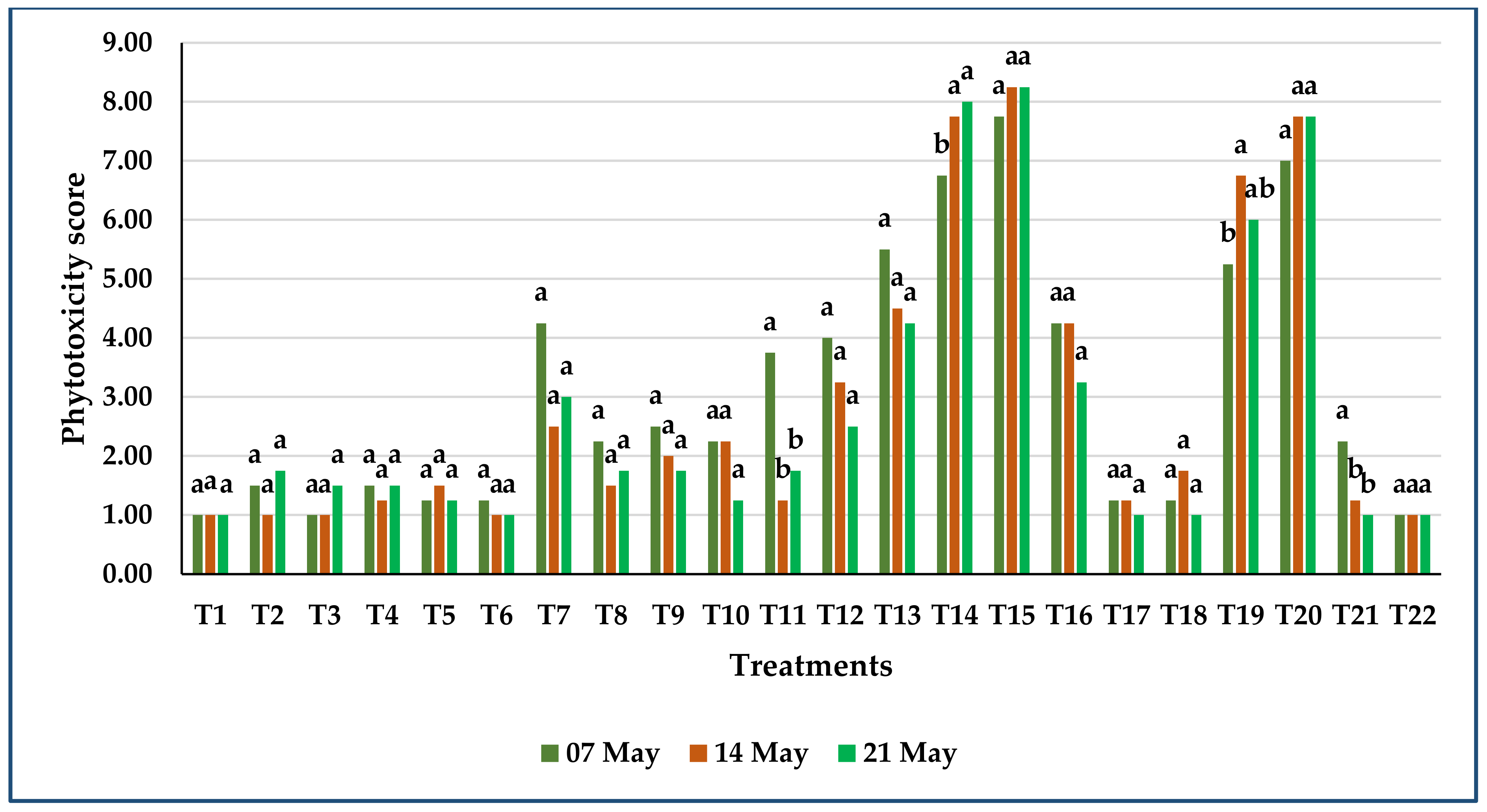

3.1.2. Phytotoxicity of Treatments on Common Vetch

3.1.3. Herbicide Efficacy on the Number of Weeds of Common Vetch

3.1.4. The Effect of Herbicides on the Seed Yield of Common Vetch

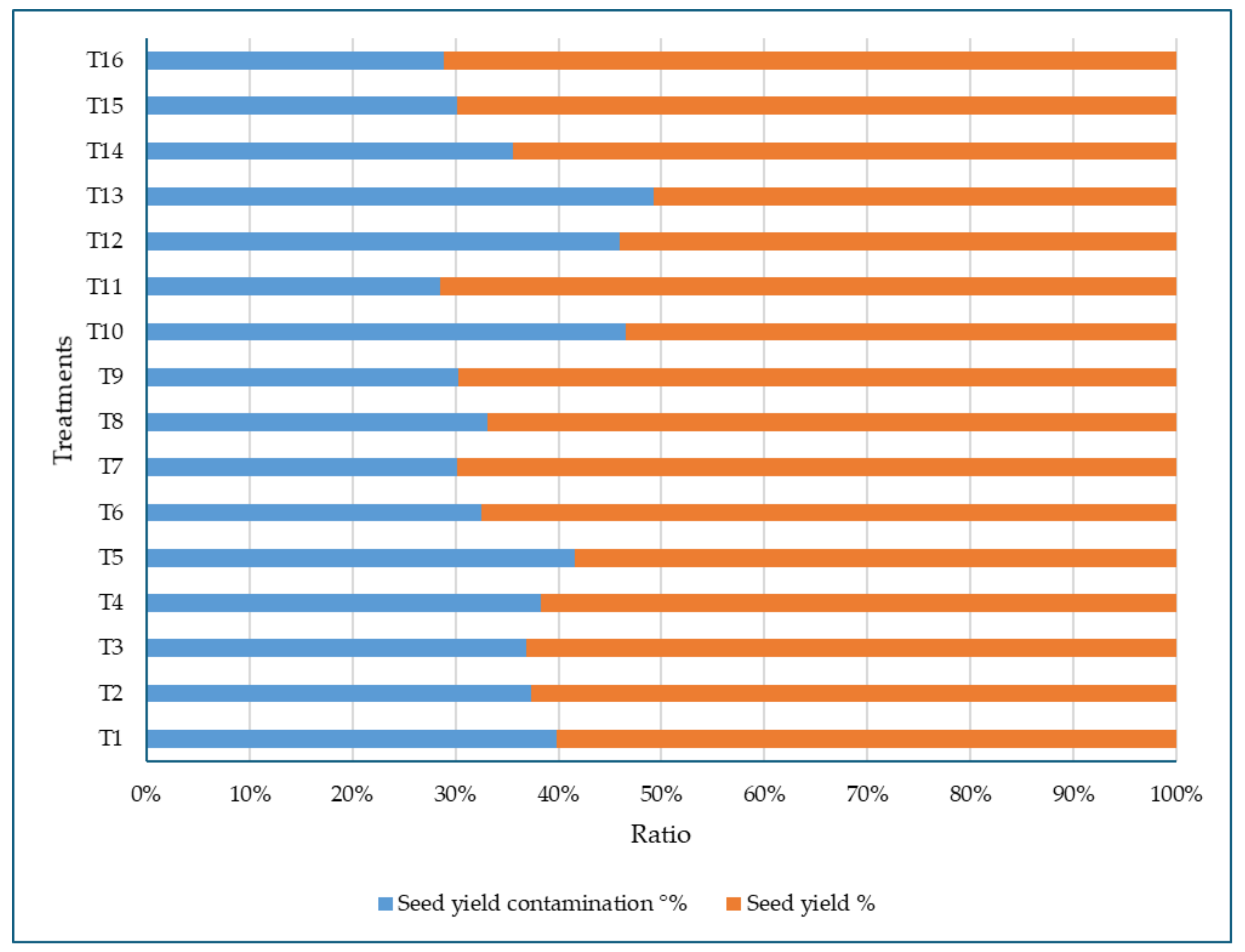

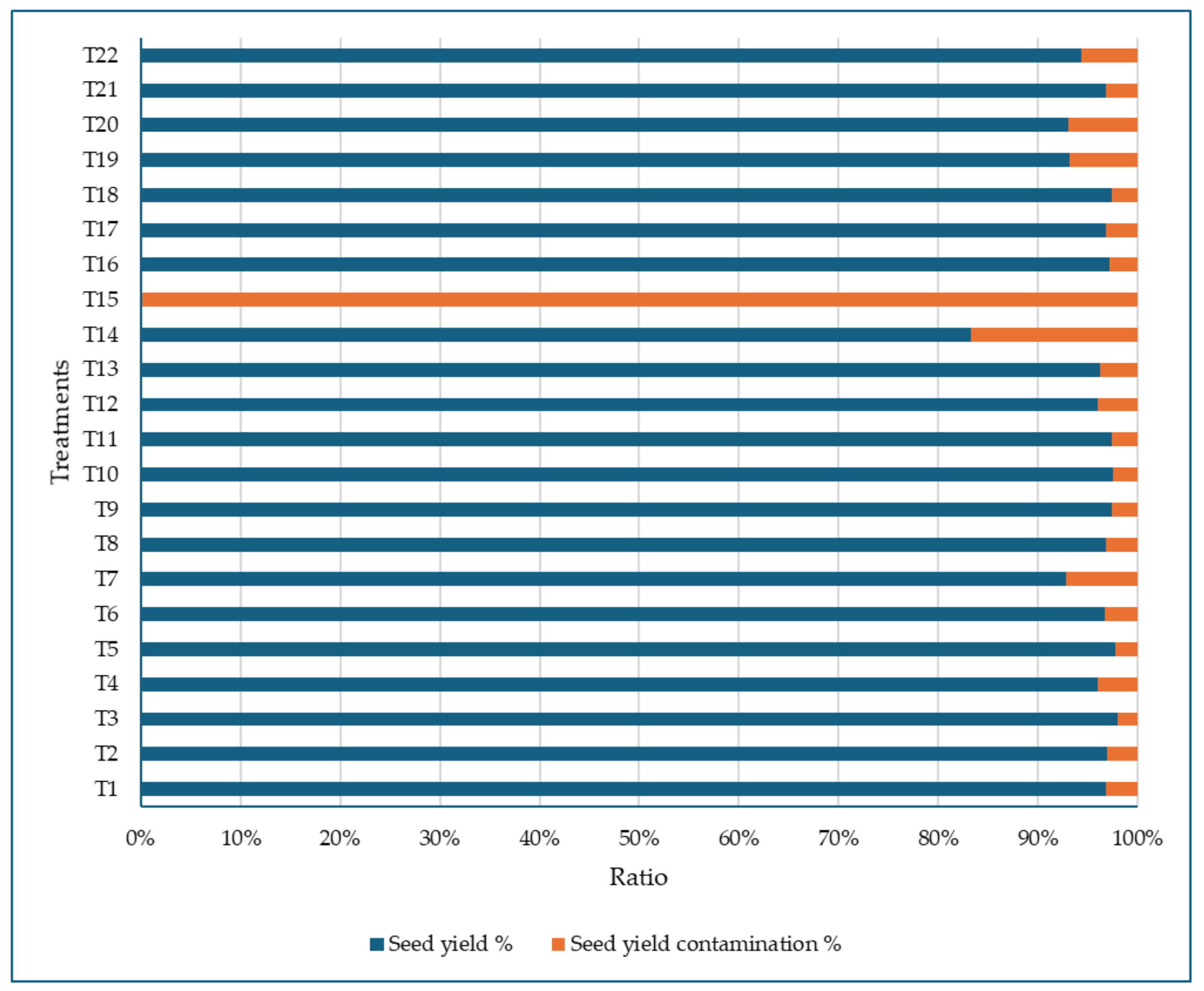

3.1.5. Seed Yield Contamination in Treated and Control Plots of Common Vetch

3.1.6. Relationship Between Variables Obtained from the First-Year Common Vetch Experiment (2023)

3.2. Results Obtained in the Second Year of the Common Vetch Experiment (2024)

3.2.1. The Effect of Treatments on the NDVI Values of Common Vetch

3.2.2. The Phytotoxicity Effect of Treatments on Common Vetch

3.2.3. Herbicide Efficacy in Reducing the Number of Weeds in Common Vetch Plots

3.2.4. Effect of Herbicides on Plant Height of Common Vetch

3.2.5. Relationships Between Variables Detected by Spearman’s Rho Correlation Test at Two Levels in Common Vetch

3.3. Results of the Herbicide Test in Sweet White Lupine (2024)

3.3.1. Effect of Herbicide Treatments on the NDVI Values of Sweet White Lupine

3.3.2. Phytotoxicity of Herbicides on Sweet White Lupine

3.3.3. Herbicide Efficacy on the Number of Weeds in Sweet White Lupine

3.3.4. Effect of Herbicides on Plant Height of Sweet White Lupine

3.3.5. The Effect of Herbicides on the Seed Yield of Sweet White Lupine

3.3.6. Seed Yield Contamination in Treated and Control Plots of Sweet White Lupine

3.3.7. Effect of Herbicides on 1000-Seed Weight in Sweet White Lupine

3.3.8. Relationship Between Parameters Assessed in Sweet White Lupine Experimental Plots

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- David, G.; Borcean, A.; Imbrea, F.; Botos, L. White lupin (Lupinus albus L.): A plant fit to improve acid soils in south-western Romania and an important source of protein. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 46, 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Daramola, D.A.; Hatzell, M.C. Energy demand of nitrogen and phosphorus based fertilizers and approaches to circularity. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Din Fahmy, A.G. Evaluation of the weed flora of Egypt from Predynastic to Graeco-Roman times. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 1997, 6, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikić, A. Presence of vetches (Vicia spp.) in agricultural and wild floras of ancient Europe. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2016, 63, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithourgidis, A.; Dordas, C.; Damalas, C.A.; Vlachostergios, D.N. Annual intercrops: An alternative pathway for sustainable agriculture. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 396–410. [Google Scholar]

- Dalias, P.; Neocleous, D. Comparative Analysis of the Nitrogen Effect ramire of Common Agricultural Practices and Rotation Systems in a Rainfed Mediterranean Environment. Plants 2017, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Parra, E.; De la Rosa, L. Designing Novel Strategies for Improving Old Legumes: An Overview from Common Vetch. Plants 2023, 12, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ačko, D.K.; Flajšman, M. Production and Utilization of Lupinus spp. In Production and Utilization of Legumes-Progress and Prospects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, B.; Marques, A.; Soriano, A.; Marquès, L.; Divol, F.; Doumas, P.; Sallet, E.; Mancinotti, D.; Carrere, S.; Marande, W.; et al. High-quality genome sequence of white lupin provides insight into soil exploration and seed quality. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsombik, L. Alternatív fehérjenövények: Lehetőség vagy örök ígéret? Anim. Breed. Feed. 2018, 67, 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Tirdiľová, I.; Vollmannová, A.; Siekel, P.; Zetochova, E.; Čéryová, S.; Trebichalský, P. Selected legumes as a source of valuable substances in human nutrition. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 59, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Prusinski, J. White lupin (Lupinus albus L.)—Nutritional and health values in human nutrition-A review. Czech J. Food Sci. 2017, 35, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiriou, I.; Polidoros, A.N.; Baira, E.; Kasiotis, K.M.; Machera, K.; Mylona, P.V. Mediterranean White Lupin Landraces as a Valuable Genetic Reserve for Breeding. Plants 2021, 10, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panneerselvam, S.; Lourduraj, A.C. Weed spectrum and effect of crop weed competition in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merrill]—A review. Agric. Rev. 2000, 21, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chandramohan, S.; Charudattan, R.; Sonoda, R.M.; Singh, M. Field evaluation of a fungal pathogen mixture for the control of seven weed grasses. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, M.; Thomas, A.; John, E. Environmental factors include management practices as correlates of weed community composition in spring seeded crops. Can. J. Bot. 1992, 70, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, T.J.; Weller, S.C.; Ashton, F.M. Weed Science: Principles and Practices; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, J.C.; Watson, D. Plants in Agriculture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Einhellig, F.A. Interactions involving allelopathy in cropping systems. Agron. J. 1996, 88, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, L.A.; Duke, S.O. Weed and crop allelopathy. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2003, 22, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.M.; Lone, F.A.; Kumar, M.; Calixto, E.S.; Waheed, M.; Casini, R.; Mahmoud, E.A.; Elansary, H.O. Phenology and Diversity of Weeds in the Agriculture and Horticulture Cropping Systems of Indian Western Himalayas: Understanding Implications for Agro-Ecosystems. Plants 2023, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sileshi, G.W.; Tessema, T. Weed Suppression in Legume Crops for Stress Management. In Climate Change and Management of Cool Season Grain Legume Crops; Yadav, S., Redden, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solh, M.B.; Palk, M. Weed control in chickpea. Options Méditerr. Sér. Sémin. 1990, 9, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, R.; Barro, C.; Alzueta, C.; Arauzo, M.; Hernaiz, P.J. Weed control and herbicide tolerance in a common vetch-oat intercrop. Weed Sci. 1995, 43, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.K.; Muniyappa, V. Parthenium phyllody disease in India. In Management of Plant Diseases Caused by Fastidious Prokaryotes: Proceedings of the Fourth Regional Workshop on Plant Mycoplasma; Raychaudhuri, S.P., Teakle, D.S., Eds.; University of Queensland: St Lucia, Australia, 1993; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sileshi, G.; Schroth, G.; Rao, M.; Girma, H. Weeds, Diseases, Insect Pests, and Tri-Trophic Interactions in Tropical Agroforestry. In Ecological Basis of Agroforestry; Batish, D.R., Kohli, R.K., Jose, S., Singh, H.P., Eds.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gyawali, A.; Bhandari, R.; Budhathoki, P.; Bhattrai, S. Management Practices. Food Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 2, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gianessi, L.P. The increasing importance of herbicides in worldwide crop production. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radchenko, M.; Guralchuk, Z.; Rodzevych, O.; Khandezhina, M.; Morderer, Y. Effectiveness of using the mixtures of herbicides flumioxazine and fluorochloridone in sunflower crops. Agric. Sci. Pract. 2022, 9, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousta, A.; Katsis, C.; Tsekoura, A.; Chachalis, D. Effectiveness and Selectivity of Pre- and Post-Emergence Herbicides for Weed Control in Grain Legumes. Plants 2024, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shield, I.; Stevenson, H.J.; Scott, T.; Leach, J.E.; Crispin, M. Evaluating herbicides for crop safety on autumn-sown white lupin. Tests Agrochem. Cultiv. 2000, 21, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Crop Protection Reference (CPR). Greenbook’s Crop Protection Reference, 27th ed.; Vance Publishing Corporation: Lenexa, KS, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mine, A.; Matsunaka, S. Mode of action of bentazon: Effect on photosynthesis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1975, 5, 444–450. [Google Scholar]

- Senseman, S.A. Herbicide Handbook, 9th ed.; Weed Science Society of America: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2007; pp. 197–199. [Google Scholar]

- Americanos, G.P.; Droushiotis, N.D. Post-emergence herbicides for forage legumes grown for seed production. Tech. Bull. 1998, 195, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, C.; Hadházy, Á.; Abido, W.; Pál, V.; Zsombik, L. Impact of some herbicides on the growth and the yield of common vetch (Vicia sativa L.). Agron. Res. 2023, 21, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivany, A.J.; Mccully, V.K. Evaluation of Herbicides for Sweet White Lupin (Lupinus albus). Weed Technol. 1994, 8, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Jiang, Z.T.; Guoand, Y.X.; Li, R. Complexation study of brilliant cresyl blue with ß-cyclodextrin and its derivatives by UV-vis and fluoros pectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 69, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnemoy, F.; Lavedrine, B.; Boulkamh, A. Influence of UV irradiation on the toxicity of phenylurea herbicides using microtox test. Chemosphere 2006, 54, 1183–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.H.; Le Yin, X.; Chen, G.F.; Yang, H. Biological responses of wheat (Triticum aestivum) plants to the herbicide chlorotoluron in soils. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 1779–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewitte, K.; Latré, J.; Haesaert, G. Possibilities of chemical weed control in Lupinus albus and Lupinus luteus-screening of herbicides. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2006, 71 Pt A, 743–751. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász, C.; Nagy, M.; Mendlerné Drienyovszki, N.; Magyarné Tábori, K.; Zsombik, L. Effect of postemergently applied herbicides on the development of sweet white lupine (Lupinus albus L.). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress on Sustainable Development in the Human Environment & Current and Future Challenges, Antalya, Turkiye, 23–26 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cremlyn, R.J. Agrochemicals: Preparation and Mode of Action; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; Volume 5, pp. 909–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; Hurd, C.; Randall, J.M. Weed control methods handbook: Tools & techniques for use in natural areas. Nat. Conserv. 2001, 4, 553. Available online: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs/533 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Grossmann, K. Auxin herbicides: Current status of mechanism and mode of action. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hura, A.K. Biological Treatment of Industrial Strength Clopyralid in Wastewaters: Biodegradation & Toxicity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, R.C.; Dalziel, J.; Matlib, A.; Somerville, L. The role of translocation in selectivity of herbicides with reference to MCPA and MCPB. Pestic. Sci. 1972, 3, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenti, I.; Borbély, F.; Kövics, G.; Bozsik, A.; Dávid, I. A lóbab (Vicia faba L.) védelme. Növényvédelem 2008, 44, 403–423. [Google Scholar]

- Pásztor, G.; Bakocs, M. A napraforgó gyomszabályozási technológiájának és herbicid érzékenységének tanulmányozása. Georg. Agric. 2022, 26, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, J.; Soltani, N.; Ashigh, J.; Hooker, D.C.; Robinson, D.E.; Sikkema, P.H. Response of soybean and corn to halauxifen-methyl. Weed Technol. 2020, 34, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, J.; Balog, A.; Nyárádi, I. Amit a Növényvédőszer Hatóanyagokról Tudni Kell; University Press: Târgu-Mureş, Romania, 2012; ISBN 978-973-169-174-9. [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, B.; Schmalfuß, J.; Böger, P. Chloroacetamide mode of action, II: Inhibition of very long chain fatty acid synthesis in higher plants. Z. Für Naturforschung C 1998, 53, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, B.; Barrentine, J.; Hayden, T.; Jacobson, B.; Kendig, A.; Krull, M.; Smith, K.L. Pethoxamid—A new herbicide for use in agronomic and horticultural crops. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of Weed Science Society of America, Lexington, KY, USA, 9–12 February 2015; Volume 281. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, N.; Brown, L.R.; Sikkema, P.H. Weed Control in White Bean with Pethoxamid Tank-Mixes Applied Preemergence. Int. J. Agron. 2018, 2018, 2402696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D.B.; Solecki, R. Dimethenamid-p/racemic dimethenamid. In Pesticide Residues in Food-2005: Toxicological Evaluations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász, C.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N.; Magyar-Tábori, K.; Radócz, L.; Zsombik, L. Effect of Different Herbicides on Development and Productivity of Sweet White Lupine (Lupinus albus L.). Agronomy 2024, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassermann, V.D. The sweet white lupins (Lupinus albus): Possibilities and agronomic practices. Techn. Commun. 1983, 184, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilakoglou, I.; Vlachostergios, D.; Dhima, K.; Lithourgidis, A. Response of vetch, lentil, chickpea and red pea to pre- or post-emergence applied herbicides. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 11, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, J.P.; Pérez, A.C.; Chantre, G.R.; Gigón, R.; Reinoso, O.; Quintana, M.; Cantamutto, M.A. Suppression of Lolium multiflorum Lam. with Vicia villosa Roth combined with residual herbicides. Rev. Investig. Agropecu. 2022, 48, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lobos, M.; Miranda, W.; Rampo, M.; Babinec, F.; Raspo, S.; Telechea, P.; Luzzi, M.; Barraco, M. Cultivos de cobertura invernales y herbicidas pre emergentes, incidencia en la densidad de una población natural de malezas. INTA EEA Gral. Villegas–Mem. Téc. 2016, 2017, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.H.; Ren, Z.L.; Liu, H.; Li, H.D.; Li, Q.S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.S.; Yao, X.K.; Cao, H.Q. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Pyrazole Sulfonamide Derivatives as Potential AHAS Inhibitors. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 66, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaleff, R.S.; Mauvais, C.J. Acetolactate synthase is the site of action of two sulfonylurea herbicides in higher plants. Science 1984, 224, 1443–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halász, A. A fehérvirágú édes csillagfürt gazdasági jelentősége, termesztésének problémái. Agrár. Közlemények 2003, 10, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S.; Chaudhry, P.; Wani, P.A.; Zaidi, A. Biotoxic effects of the herbicides on growth, seed yield, and grain protein of greengram. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2006, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. European Food Safety Authority Scientific Report; EFSA: Parma, Italy, 2008; Volume 195, pp. 1–115. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/195r.html (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Hinds-Cook, B.J.; Curtis, D.W.; Hulting, A.G.; Mallory-Smith, C.A. Postemergence grass control options in vetch grown for seed. Seed Prod. Res. 2021, 129, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, S.O.; Dayan, F.E. Bioactivity of herbicides. In Comprehensive Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Murray, M.Y., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 4, pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chamovitz, D.; Sandmann, G.; Hirschberg, J. Molecular and biochemical characterization of herbicide-resistant mutants of cyanobacteria reveals that phytoene desaturation is a rate-limiting step in carotenoid biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 17348–17353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliva, J.H. Herbicidas Preemergentes en el Cultivo de Vicia villosa Roth: Evaluación de Selectividad en un Cultivo Del Área Central de la Provincia de Córdoba. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Católica de Córdoba, Cordoba, Argentina, 2020; 25p. [Google Scholar]

- Pál, V.; Zsombik, L. Evaluation of the role of common vetch (Vicia sativa L.) green manure in crop rotations. Acta Agrar. Debreceniensis 2022, 1, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatala, Z. The Practical Application of Precision Horticultural Technologies. Master’s Thesis, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, 2012; 54p. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the Conduct of Tests for Distinctness, Uniformity and Stability; Common Vetch, Vicia sativa L., (TGP/7/1); 2013. Available online: https://www.upov.int/edocs/tgdocs/en/tg032.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Lupinus Albus, White Lupin, Crop Production Guide. Available online: https://www.dsv-seeds.com/epaper/dsv-seeds.com/WhiteLupinProductionGuide/#0 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Sinde-González, I.; Falconí-Saá, C.E.; Luna-Granizo, P.; Godoy-Guanín, L.; Gil-Docampo, M.d.l.L.; Maiguashca, J.; Nato, R. Spectral analysis of the phenological stages of Lupinus mutabilis through spectroradiometry and unmanned aerial vehicle imaging with different physical disinfection pretreatments of seeds. Geocarto Int. 2021, 37, 7143–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasca, S.C.; Spaeth, M.; Rusu, T.; Bogdan, I. Mechanical Weed Control: Sensor-Based Inter-Row Hoeing in Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) in the Transylvanian Depression. Agronomy 2024, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Roy, M.; Roy, B.; Deka, S.D. Post harvest management strategies and storage approaches for quality seed production. In Emerging Issues in Agricultural Sciences; Al-Naggar, A.M.M., Ed.; BP International: London, UK, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 110–129. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, A.; Dines, L. Lockhart and Wiseman’s Crop Husbandry Including Grassland, 10th ed.; Samuel, A., Dines, L., Eds.; (szerk) 5—Weeds of farm crops; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2023; pp. 115–141. ISBN 9780323857024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pause, M.; Raasch, F.; Marrs, C.; Csaplovics, E. Monitoring Glyphosate-Based Herbicide Treatment Using Sentinel-2 Time Series—A Proof-of-Principle. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.W.; Toth, Z. Effect of drought stress on morphology, yield, and chlorophyll concentration of Hungarian potato genotypes. J. Environ. Agric. Sci. 2021, 23, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Golzarian, M.R.; Frick, R.A.; Rajendran, K.; Berger, B.; Roy, S.; Tester, M.; Lun, D.S. Accurate inference of shoot biomass from high-throughput images of cereal plants. Plant Methods 2011, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma-Natu, P.; Ghildiyal, M. Potential targets for improving photosynthesis and crop yield. Curr. Sci. 2005, 88, 1918–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Travlos, I.; Tsekoura, A.; Antonopoulos, N.; Kanatas, P.; Gazoulis, I. Novel sensor-based method (quick test) for the in-season rapid evaluation of herbicide efficacy under real field conditions in durum wheat. Weed Sci. 2021, 69, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak, S.; Başayığıt, L.; Türk, M. Use of canopy- and leaf-reflectance indices for the detection of quality variables of Vicia species. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germida, J.J.; Slinkard, A.E.; Nelson, L.M.; McKercher, R.B. Effect of herbicides on growth and nitrogen fixation potential (ARA) of field pea and lentil. In Soils and Crops Workshop; University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 1986; pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász, C.; Zsombik, L. Különböző gyomírtószerek hatása a szöszös bükköny (Vicia villosa Roth.) fejlődésére. In 39. Óvári Tudományos Nap: Konferencia: “Az agrár-, élelmiszer- és vidékgazdaság kihívásai”: Absztrakt kötet. Szerk.: Molnár Zoltán, Némethné Wurm Katalin; Széchenyi István University: Mosonmagyaróvár, Hungary, 2023; p. 93. ISBN 9786156443243. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, R.; Serpeille, A. Essais de desherbage des cultures de pois, feverole, vesce et lupin. In Compte Rendu de la IIe Conference du COLUMA; Comité français de lutte contre les mauvaises herbes; Fédération nationale des groupements de protection des cultures: Paris, France, 1981; Volume 2, pp. 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, N.; Nurse, R.E.; Sikkema, P.H. Sensitivity of adzuki, kidney, small red Mexican, and white beans to pethoxamid. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 98, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, D.; Leep, R.H.; Roggenbucb, F.C.; Lempke, J.R. Herbicide efficacy and tolerance in sweet white lupin. Weed Technol. 1993, 7, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, C.M. Tolerance of autumn-sown determinate lupins (Lupinus albus) to herbicides. Test Agrochem. Cultiv. 1996, 17, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, A. Chemical Weed Control and Crop Control, 6th ed.; Mezőgazda Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2019; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, M.F.; Morrison, I.N. Fall and spring applications of trifluralin and metribuzin in fababeans (Vicia faba). Weed Sci. 1979, 27, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.A.; Renner, K.A.; Penner, D. Weed control in soybean (Glycine max) with imazamox and imazethapyr. Weed Sci. 1998, 46, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loux, M.; Liebl, R.; Slife, F. Availability and Persistence of Imazaquin, Imazethapyr, and Clomazone in Soil. Weed Sci. 1989, 37, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Briggs, G. The fate of the herbicide chlortoluron and its possible degradation products in soils. Weed Res. 1978, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkiel, M.; Baćmaga, M.; Borowik, A.; Wyszkowska, J.; Kucharski, J. The sensitivity of soil enzymes, microorganisms and spring wheat to soil contamination with carfentrazone-ethyl. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2018, 53, 107–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftherohorinos, I.; Dhima, K.; Vasilakoglou, I. Activity, adsorption, mobility and field persistence of sulfosulfuron in soil. Phytoparasitica 2004, 32, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivany, J.; Sadler, J.; Kimball, E. Rate of Metribuzin Breakdown and Residue Effects on Rotation Crops. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1983, 63, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of Soil | Indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | |

| pH (KCl) | 7.66 | 7.4 |

| Plasticity Index by Arany 3 | 34 | 30 |

| Water-soluble salt % 1 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Carbonated lime content % 1 | 5.84 | 2.42 |

| Humus content (SOM) 2 % 1 | 1.63 | 1.53 |

| Phosphorus pentoxide mg kg−1 | 347 | 231 |

| Potassium oxide mg kg−1 | 340 | 263 |

| Active Substances | Time of Application | Herbicide Application Rate | Doses of Active Ingredient | Treatment Codes | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flumioxazin | Post-emergence | 0.06 kg·ha−1 | 30 g ai·ha−1 | T1 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Flumioxazin | Post-emergence | 0.08 kg·ha−1 | 40 g ai·ha−1 | T2 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Chlorotoluron | Post-emergence | 2.8 L·ha−1 | 1400 g ai·ha−1 | T3 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Chlorotoluron | Post-emergence | 3.0 L·ha−1 | 1500 g ai·ha−1 | T4 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Clopyralid + picloram | Post-emergence | 0.3 L·ha−1 | 80 + 20 g ai·ha−1 | T5 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac | Post-emergence | 2.0 L·ha−1 | 666 + 166 g ai·ha−1 | T6 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac | Post-emergence | 2.25 L·ha−1 | 749 + 187 g ai·ha−1 | T7 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| MCPB | Post-emergence | 2.0 L·ha−1 | 876 g ai·ha−1 | T8 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| MCPB | Post-emergence | 3.0 L·ha−1 | 1314 g ai·ha−1 | T9 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| Triflusulfuron-methyl | Post-emergence | 20.0 g·ha−1 | 10 g ai ha−1 | T10 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Triflusulfuron-methyl + ethoxylated isodecyl alcohol (adjuvant) | Post-emergence | 20.0 g ha−1 | 10 g ai·ha−1 | T11 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Sulfosulforon | Post-emergence | 10.0 g·ha−1 | 7.5 g ai·ha−1 | T12 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl | Post-emergence | 15.0 g ha−1 | 7.5 g ai·ha−1 | T13 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl + ethoxylated isodecyl alcohol (adjuvant) | Post-emergence | 15.0 g·ha−1 | 7.5 g ai ha−1 | T14 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Bentazon | Post-emergence | 1.5 L·ha−1 | 720 g ai·ha−1 | T15 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Control | - | - | - | T16 | - |

| Active Substances | Time of Application | Herbicide Application Rate | Doses of Active Ingredients | Treatment Codes | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pendimethalin | Pre-emergence | 5.0 L·ha−1 | 2275 g ai·ha−1 | T1 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| S-metolachlor | Pre-emergence | 1.4 L·ha−1 | 1344 g ai·ha−1 | T2 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| Flumioxazin | Pre-emergence | 0.06 kg·ha−1 | 30 g ai·ha−1 | T3 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Clomazone | Pre-emergence | 0.2 L·ha−1 | 96 g ai·ha−1 | T4 | Inhibition of carotenoid biosynthesis |

| Metribuzin | Pre-emergence | 0.55 L·ha−1 | 330 g ai·ha−1 | T5 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Flumioxazin | Post-emergence | 0.06 kg·ha−1 | 30 g ai·ha−1 | T6 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Flumioxazin | Post-emergence | 0.08 kg·ha−1 | 40 g ai·ha−1 | T7 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Chlorotoluron | Post-emergence | 2.8 L·ha−1 | 1400 g ai·ha−1 | T8 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Chlorotoluron | Post-emergence | 3.0 L·ha−1 | 1500 g ai·ha−1 | T9 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Clopyralid + picloram | Post-emergence | 0.3 L·ha−1 | 80 + 20 g ai·ha−1 | T10 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac | Post-emergence | 2.0 L·ha−1 | 666 + 166 g ai·ha−1 | T11 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac | Post-emergence | 2.25 L·ha−1 | 749 + 187 g ai·ha−1 | T12 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| MCPB | Post-emergence | 2.0 L·ha−1 | 876 g ai·ha−1 | T13 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| MCPB | Post-emergence | 3.0 L·ha−1 | 1314 g ai·ha−1 | T14 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| Sulfosulforon | Post-emergence | 10.0 g·ha−1 | 7.5 g ai·ha−1 | T15 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl | Post-emergence | 15.0 g·ha−1 | 7.5 g ai·ha−1 | T16 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl + ethoxylated isodecyl alcohol | Post-emergence | 15.0 g·ha−1 | 7.5 g ai·ha−1 | T17 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Bentazon | Post-emergence | 1.5 l·ha−1 | 720 g ai·ha−1 | T18 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Imazamox | Post-emergence | 0.8 l·ha−1 | 32 g ai·ha−1 | T19 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Control | - | - | - | T20 | - |

| Active Substances | Time of Application | Herbicide Application Rate | Doses of Active Ingredients | Treatment Codes | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flumioxazin | Pre-emergence | 0.06 kg·ha−1 | 30 g ai·ha−1 | T1 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Pendimethalin | Pre-emergence | 5.0 L·ha−1 | 2275 g ai·ha−1 | T2 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| Dimethenamid-P | Pre-emergence | 1.4 l·ha−1 | 1008 g ai·ha−1 | T3 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| Pethoxamid | Pre-emergence | 2.0 L·ha−1 | 1200 g ai·ha−1 | T4 | Germination and growth inhibition |

| Clomazone | Pre-emergence | 0.2 L·ha−1 | 96 g ai·ha−1 | T5 | Inhibition of carotenoid biosynthesis |

| Metobromuron | Pre-emergence | 3.0 L·ha−1 | 1500 g ai·ha−1 | T6 | Photosynthesis inhibition |

| Metribuzin | Pre-emergence | 0.55 L·ha−1 | 330 g ai·ha−1 | T7 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Diflufenican | Pre-emergence | 0.25 L·ha−1 | 125 g ai·ha−1 | T8 | Phytoene desaturase inhibition |

| Flumioxazin | Post-emergence | 0.06 kg·ha−1 | 30 g ai·ha−1 | T9 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Chlorotoluron | Post-emergence | 2.8 L·ha−1 | 1400 g ai·ha−1 | T10 | Photosynthesis inhibition in the Ps II |

| Halauxifen-methyl | Late post-emergence | 0.4 L·ha−1 | 1.3 g ai·ha−1 | T11 | Auxin effect |

| Halauxifen-methyl | Late post-emergence | 0.5 L·ha−1 | 1.6 g ai·ha−1 | T12 | Auxin effect |

| Halauxifen-methyl | Late post-emergence | 0.6 L·ha−1 | 1.9 g ai·ha−1 | T13 | Auxin effect |

| Halauxifen-methyl + picloram | Late post-emergence | 0.25 L·ha−1 | 2.5 + 12 g ai·ha−1 | T14 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| Halauxifen-methyl + picloram | Late post-emergence | 0.5 L·ha−1 | 5 + 24 g ai·ha−1 | T15 | Respiratory metabolism stimulant (synthetic auxin) |

| Prosulfocarb | Post-emergence | 2.5 L·ha−1 | 2000 g ai·ha−1 | T16 | Lipid biosynthesis inhibition |

| Carfentrazone-ethyl | Post-emergence | 35.0 g·ha−1 | 14 g ai·ha−1 | T17 | Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition |

| Sulfosulfuron | Post-emergence | 13.0 g·ha−1 | 9.8 g ai·ha−1 | T18 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Sulfosulfuron | Post-emergence | 17.0 g·ha−1 | 12.8 g ai·ha−1 | T19 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Imazamox | Post-emergence | 1.0 L·ha−1 | 40 g ai·ha−1 | T20 | Acetolactate synthase inhibitors |

| Diflufenican | Post-emergence | 0.25 L·ha−1 | 125 g ai·ha−1 | T21 | Phytoene desaturase inhibition |

| Control | - | - | - | T22 | - |

| Active Substances | Treatment Codes | Phytotoxicity Score 1 | Number of Weeds 0.25 m−2 | Yield kg ha−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flumioxazin | T1 | 3.88 ef | 0.5 b | 511abc |

| Flumioxazin | T2 | 4.0 ef | 0.8 b | 560 abc |

| Chlorotoluron | T3 | 3.75 ef | 4.0 ab | 647 a |

| Chlorotoluron | T4 | 2.38 g | 1.3 b | 467 a–d |

| Clopyralid + picloram | T5 | 8.5 a | 7.0 a | 307 cde |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac | T6 | 4.63 def | 0.8 b | 633 ab |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac | T7 | 3.38 fg | 1.5 b | 567 abc |

| MCPB | T8 | 4.13 ef | 1.8 b | 413 a–d |

| MCPB | T9 | 4.0 ef | 1.3 b | 427 a–d |

| Triflusulfuron-methyl | T10 | 5.88 cd | 3.5 ab | 117 e |

| Triflusulfuron-methyl + adjuvant | T11 | 5.63 cd | 2.8 b | 350 b–e |

| Sulfosulforon | T12 | 7.75 ab | 2.3 b | 180 de |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl | T13 | 6.63 bc | 2.0 b | 177 de |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl + adjuvant | T14 | 5.88 cd | 1.0 b | 283 cde |

| Bentazon | T15 | 5.13 de | 4.0 ab | 652 a |

| Control | T16 | 1.0 h | 1.0 b | 520 abc |

| NDVI Data | Phytotoxicity | Number of Weeds | Contamination | Seed Yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI data | 1 | ||||

| Phytotoxicity | −0.783 ** | 1 | |||

| Number of weeds | −0.344 ** | 0.295 * | 1 | ||

| Contamination | 0.368 ** | −0.316 * | 0.017 | 1 | |

| Seed yield | 0.618 ** | −0.493 ** | −0.14 | 0.656 ** | 1 |

| |||||

| Active Substances | Treatment Codes | Phytotoxicity Score 1 | Number of Weeds 0.25 m−2 | Plant Height cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pendimethalin (pre-emergence) | T1 | 1.94 ef | 0.8 ab | 39.9 ab |

| S-metolachlor (pre-emergence) | T2 | 1.13 fg | 0.5 ab | 44.4 a |

| Flumioxazin (pre-emergence) | T3 | 1.06 g | 0.0 b | 44.8 a |

| Clomazone (pre-emergence) | T4 | 1.00 g | 0.5 ab | 47.4 a |

| Metribuzin (pre-emergence) | T5 | 1.94 ef | 0.0 b | 46.8 a |

| Flumioxazin (post-emergence) | T6 | 1.81 efg | 0.0 b | 44.0 a |

| Flumioxazin (post-emergence) | T7 | 1.50 fg | 0.0 b | 41.5 a |

| Chlorotoluron (post-emergence) | T8 | 3.63 d | 0.8 ab | 42.9 a |

| Chlorotoluron (post-emergence) | T9 | 2.38 e | 0.0 b | 40.3 ab |

| Clopyralid + picloram (post-emergence) | T10 | 8.75 a | 0.5 ab | 0.0 e |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac (post-emergence) | T11 | 1.00 g | 0.0 b | 44.3 a |

| Metazachlor + quinmerac (post-emergence) | T12 | 1.00 g | 0.3 ab | 45.3 a |

| MCPB (post-emergence) | T13 | 4.19 d | 0.3 ab | 46.2 a |

| MCPB (post-emergence) | T14 | 5.63 c | 0.3 ab | 39.4 ab |

| Sulfosulforon (post-emergence) | T15 | 6.63 b | 0.0 b | 15.6 d |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl (post-emergence) | T16 | 5.31 c | 0.5 ab | 31.8 bc |

| Thifensulfuron-methyl + ethoxylated isodecyl alcohol (post-emergence) | T17 | 5.88 bc | 0.3 ab | 24.6 c |

| Bentazon (post-emergence) | T18 | 5.88 bc | 0.0 b | 41.0 ab |

| Imazamox (post-emergence) | T19 | 4.38 d | 1.0 a | 38.8 ab |

| Control | T20 | 1.00 g | 0.3 ab | 45.9 a |

| NDVI | Phytotoxicity Scores | Number of Weeds | Height of Plants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | 1 | |||

| Phytotoxicity scores | −0.936 ** | 1 | ||

| Number of weeds | −0.049 | 0.087 | 1 | |

| Height of plants | 0.53 ** | −0.558 ** | −0.094 | 1 |

| ||||

| Active Substances | Treatment Codes | PhytotoxicityScore 1 | Number of Weeds 0.25 m−2 | Plant Height cm | Yield kg ha−1 | 1000-Seed Weight g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flumioxazin (pre-emergence) | T1 | 1.00 f | 0.9 a | 52.4 a | 1847 ab | 290 a |

| Pendimethalin (pre-emergence) | T2 | 1.42 f | 1.1 a | 47.1 a–d | 1374 abc | 284 a |

| Dimethenamid-P (pre-emergence) | T3 | 1.17 f | 0.6 a | 46.9 a–d | 1506 abc | 305 a |

| Pethoxamid (pre-emergence) | T4 | 1.42 f | 0.4 a | 45.2 a–d | 1416 abc | 299 a |

| Clomazone (pre-emergence) | T5 | 1.33 f | 0.5 a | 49.4 ab | 1906 a | 311 a |

| Metobromuron (pre-emergence) | T6 | 1.08 f | 1.1 a | 48.0 abc | 1834 ab | 304 a |

| Metribuzin (pre-emergence) | T7 | 3.25 de | 0.5 a | 48.3 abc | 1248 bc | 304 a |

| Diflufenican (pre-emergence) | T8 | 1.83 f | 0.5 a | 47.8 abc | 1540 abc | 300 a |

| Flumioxazin (post-emergence) | T9 | 2.08 ef | 0.9 a | 46.6 a–d | 1537 abc | 294 a |

| Chlorotoluron (post-emergence) | T10 | 1.92 f | 0.3 a | 41.1 b–e | 1597 abc | 302 a |

| Halauxifen-methyl (post-emergence) | T11 | 2.25 ef | 0.5 a | 48.8 abc | 1691 ab | 330 a |

| Halauxifen-methyl (post-emergence) | T12 | 3.25 de | 0.4 a | 52.2 a | 1500 abc | 320 a |

| Halauxifen-methyl (post-emergence) | T13 | 4.75 c | 0.4 a | 41.5 b–e | 988 c | 330 a |

| Halauxifen-methyl + picloram (post-emergence) | T14 | 7.50 a | 0.3 a | 31.5 fg | 88 d | 269 ab |

| Halauxifen-methyl + picloram (post-emergence) | T15 | 8.08 a | 0.1 a | 0.0 h | 0 d | 0 c |

| Prosulfocarb (post-emergence) | T16 | 3.92 cd | 0.1 a | 39.8 de | 1397 abc | 312 a |

| Carfentrazone-ethyl (post-emergence) | T17 | 1.17 f | 1.3 a | 47.8 abc | 1672 ab | 295 a |

| Sulfosulfuron (post-emergence) | T18 | 1.33 f | 0.5 a | 44.8 a–d | 1447 abc | 306 a |

| Sulfosulfuron (post-emergence) | T19 | 6.00 b | 0.5 a | 35.1 ef | 381 d | 292 a |

| Imazamox (post-emergence) | T20 | 7.50 a | 0.3 a | 28.1 g | 157 d | 224 b |

| Diflufenican (post-emergence) | T21 | 1.50 f | 0.8 a | 45.2 a–d | 1775 ab | 306 a |

| Control | T22 | 1.00 f | 0.5 a | 51.3 a | 1431 abc | 284 a |

| NDVI | Phytotoxicity Scores | Number of Weeds | Height of Plants | Seed Yield Contamination | Seed Yield | 1000-Seed Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | 1 | ||||||

| Phytotoxicity scores | −0.88 ** | 1 | |||||

| Number of weeds | 0.381 ** | −0.325 ** | 1 | ||||

| Height of plants | 0.843 ** | −0.712 ** | 0.316 ** | 1 | |||

| Seed yield contamination | 0.586 ** | −0.568 ** | 0.227 * | 0.544 ** | 1 | ||

| Seed yield | 0.779 ** | −0.748 ** | 0.257 * | 0.737 ** | 0.593 ** | 1 | |

| 1000-seed weight | 0.192 | −0.132 | 0.026 | 0.305 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.485 ** | 1 |

| |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juhász, C.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N.; Magyar-Tábori, K.; Zsombik, L. Evaluation of Chemical Weed-Control Strategies for Common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) and Sweet White Lupine (Lupinus albus L.) Under Field Conditions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15040916

Juhász C, Mendler-Drienyovszki N, Magyar-Tábori K, Zsombik L. Evaluation of Chemical Weed-Control Strategies for Common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) and Sweet White Lupine (Lupinus albus L.) Under Field Conditions. Agronomy. 2025; 15(4):916. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15040916

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuhász, Csaba, Nóra Mendler-Drienyovszki, Katalin Magyar-Tábori, and László Zsombik. 2025. "Evaluation of Chemical Weed-Control Strategies for Common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) and Sweet White Lupine (Lupinus albus L.) Under Field Conditions" Agronomy 15, no. 4: 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15040916

APA StyleJuhász, C., Mendler-Drienyovszki, N., Magyar-Tábori, K., & Zsombik, L. (2025). Evaluation of Chemical Weed-Control Strategies for Common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) and Sweet White Lupine (Lupinus albus L.) Under Field Conditions. Agronomy, 15(4), 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15040916