A Novel Composite Amendment for Soda Saline–Alkali Soils: Reducing Alkalinity, Enhancing Nutrient Content, and Increasing Maize Yield

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Testing Materials

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Sample Collection and Determination

2.5. Soil Quality Index

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Soil Salts Ions, Salinization, and Alkalization Parameters

3.2. Soil Nutrients

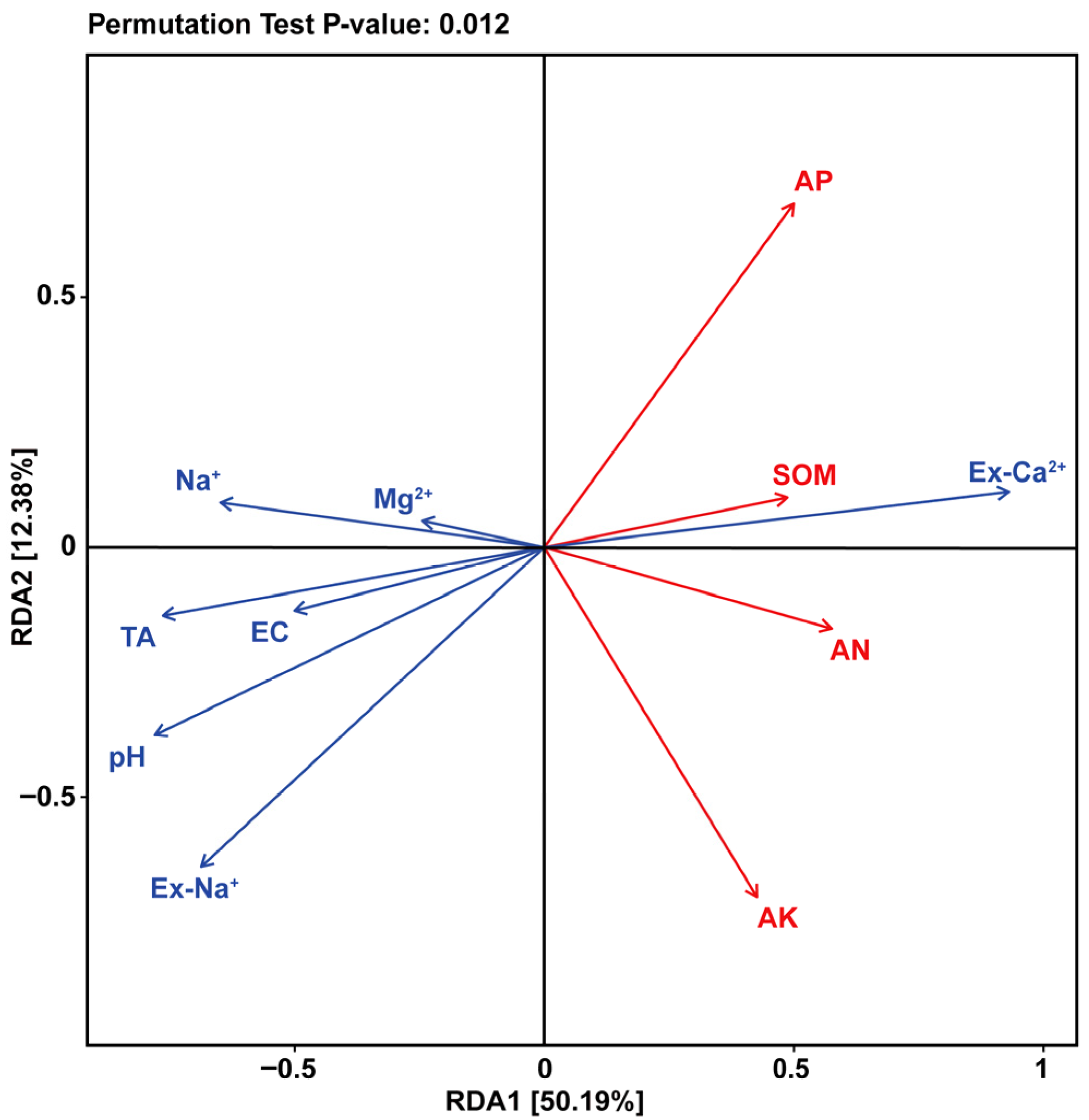

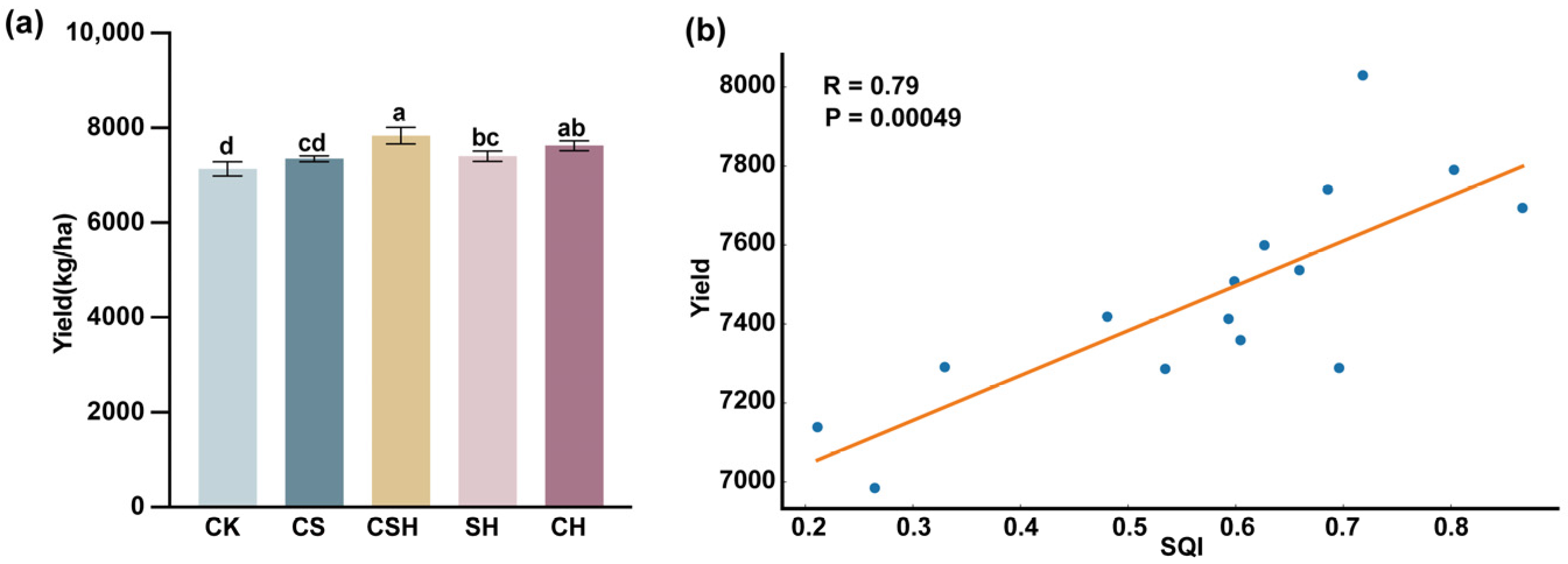

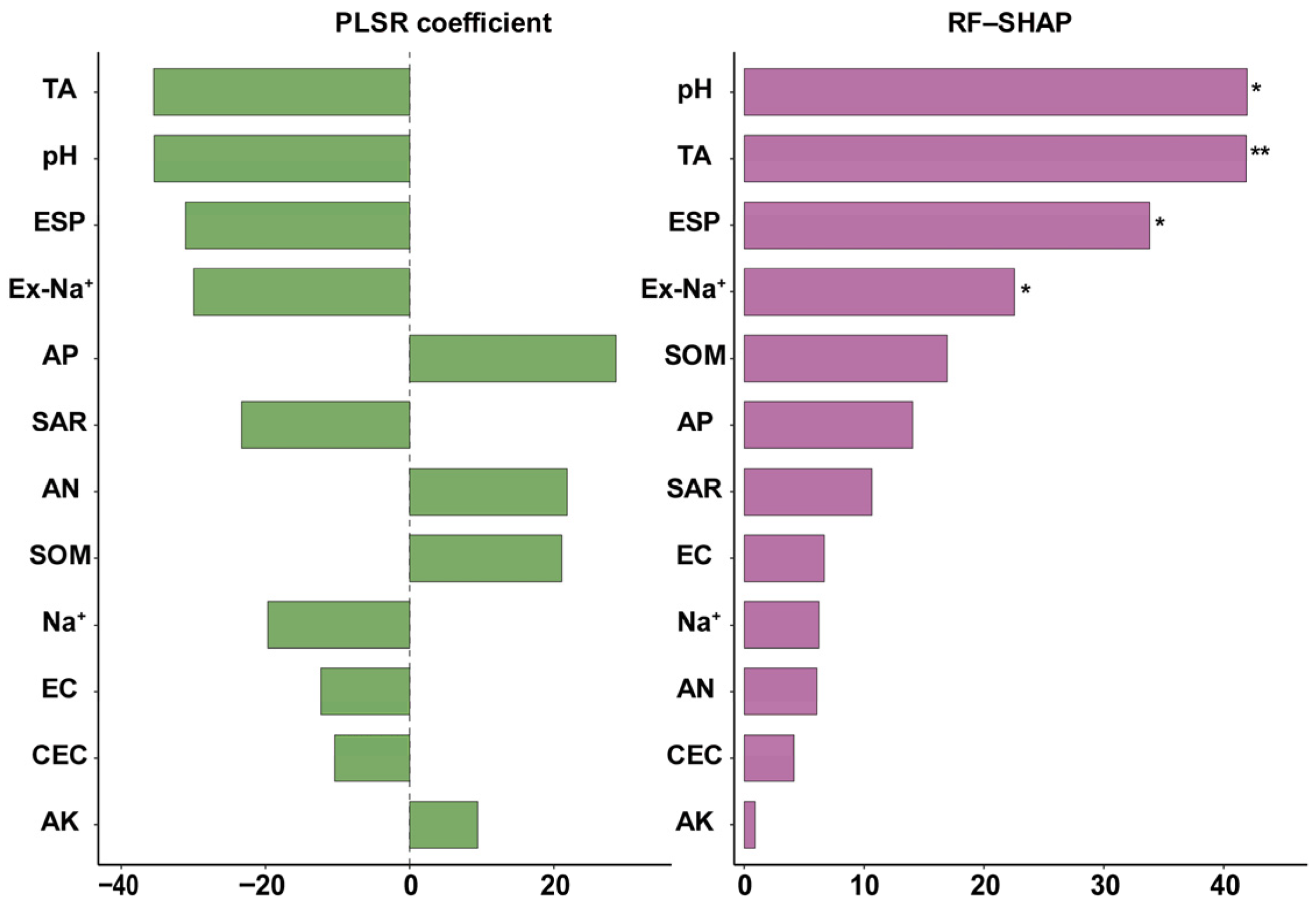

3.3. Soil Quality Index

3.4. Mazie Yield

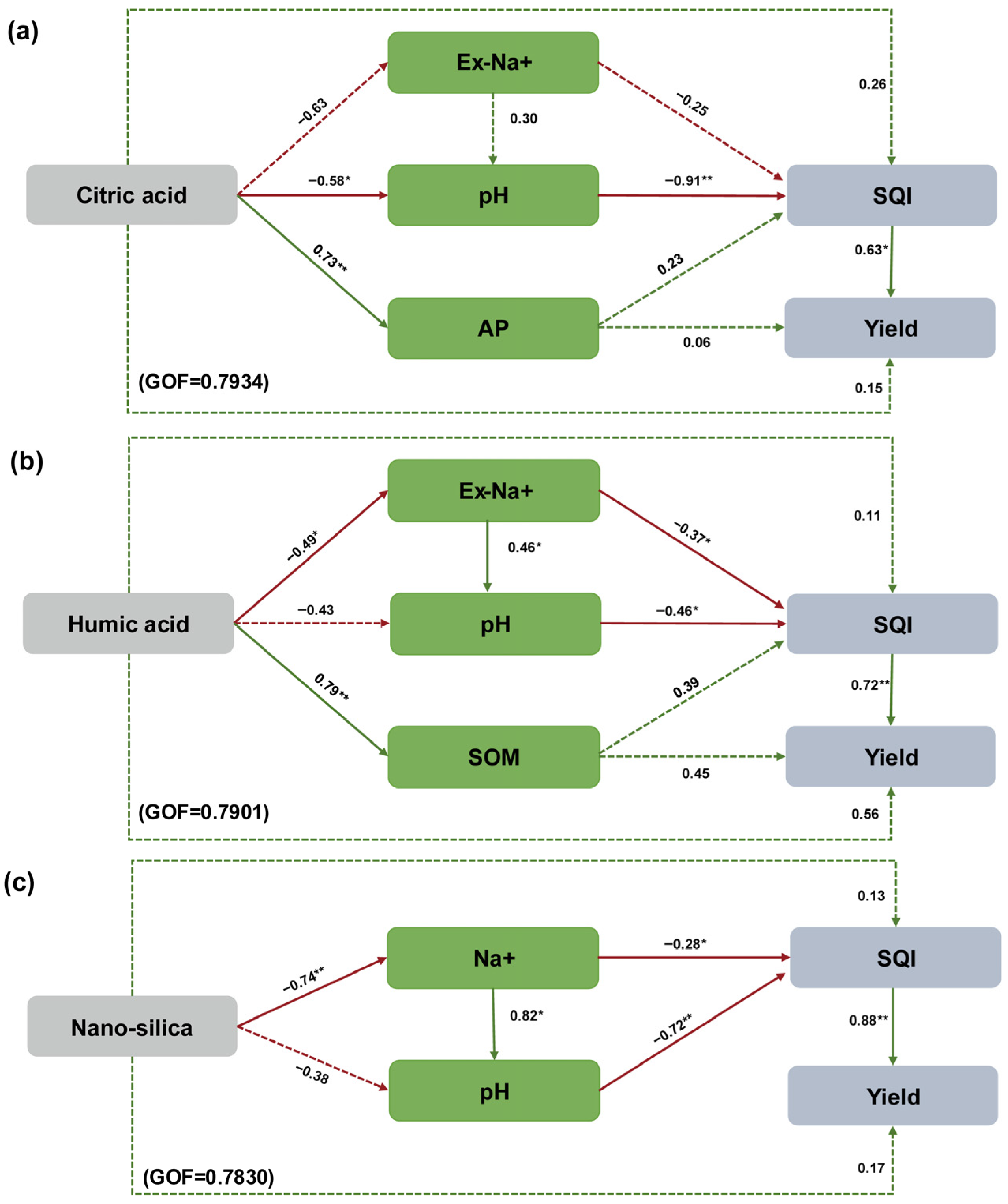

3.5. Partial Least Squares Path Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Adding Amendments on Soil Saline–Alkali Characteristics

4.2. Effects of Adding Amendments on Soil Nutrients

4.3. Effect of Adding Amendments on Soil Quality and Maize Yield

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fei, Y.; Jiao, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, B.; Song, R.; Meng, Z.; Liu, B.; Wu, J.; Qi, C.; Zhou, W.; et al. A Sulfate-Palygorskite Composite Amendment for Saline-alkali Soil: Simultaneous Alkalinity Reduction, Nutrient Enrichment, and Crop Growth Promotion. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 256, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z. Water and Salt Migration Characterization in NaHCO3 Saline Soils During Unidirectional Freezing Conditions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 213, 103940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Effects of the Interaction between Biochar and Nutrients on Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration in Soda Saline-alkali Grassland: A review. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 26, e01449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedifar, M. Effect of Biochar on Cadmium Fractions in Some Polluted Saline and Sodic Soils. Environ. Manag. 2020, 66, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, B.; Yan, B. Optimizing Fertilizer Usage for Source Reduction of Salt and Fluoride Ion Runoff Discharge from a Soda Saline-alkali Paddy Field. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 364, 121489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Lei, L.; Zou, D.; et al. QTL Mapping and Candidate Gene Analysis for Alkali Tolerance in Japonica Rice at the bud Stage Based on Linkage Mapping and Genome-Wide Association Study. Rice 2020, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yao, R.; Wang, X.; Xie, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, L.; Sun, R. Research on Salt-Affected Soils in China: History, Status Quo and Prospect. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2022, 59, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hang, X.; Zhao, L. Study on Function of Aluminum Sulfate on Soda Alkali-saline Soil Improvement. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2006, 04, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Ferreira, J.F.S.; Wang, M.; Na, J.; Huang, J.; Liang, Z. Long-term Combined Effects of Tillage and Rice Cultivation with Phosphogypsum or Farmyard Manure on the Concentration of Salts, Minerals, and Heavy metals of Saline-sodic Paddy Fields in Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 215, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.S.B.; Tanyton, T.W. Gypsum Applications to Aggregated Saline—Sodic Clay Topsoils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1992, 43, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z. The long-term Effects of Cattle Manure Application to Agricultural Soils as a Natural-Based Solution to Combat Salinization. CATENA 2019, 175, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Zhong, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, R.; Feng, H.; Dong, Q.g.; Yang, Y. Application of Biochar in Saline Soils Enhances Soil Resilience and Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Arid Irrigation Areas. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 250, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiek, E. Citric Acid: Properties, Microbial Production, and Applications in Industries. Molecules 2024, 29, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igliński, B.; Kiełkowska, U.; Piechota, G. Proecological Aspects of Citric Acid Technology. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 2061–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sinha, M.; Sharma, K.; Koteswararao, R.; Cho, M.H. Modern Extraction and Purification Techniques for Obtaining High Purity Food-Grade Bioactive Compounds and Value-Added Co-Products from Citrus Wastes. Foods 2019, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, B.; Wang, H.; Duan, M.; Feng, L. Effects of Different Soil Amendments on Physicochemical Property of Soda Saline-alkali Soil and Crop Yield in Northeast China. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, T.; Qiblawey, H.; Almomani, F.; Al-Raoush, R.I.; Han, D.S.; Ahmad, N.M. Recent Advances on Humic Acid Removal from Wastewater Using Adsorption Process. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Chang, F.; Yu, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y. Humic Acid Plus Manure Increases the Soil Carbon Pool by Inhibiting Salinity and Alleviating the Microbial Resource Limitation in Saline Soils. CATENA 2023, 233, 107527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Li, P.; Tian, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xue, B. Preliminary Studies on How to Reduce the Effects of Salinity. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, R.; Mohammed, B.S. Properties of Rubberized Engineered Cementitious Composites Containing Nano-Silica. Materials 2021, 14, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, K.; Rashwan, E.A.; Hussein, H.; Awadalla, A.O.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Hafez, E.; Alshaal, T. Application of Silica Nanoparticles in Combination with Two Bacterial Strains Improves the Growth, Antioxidant Capacity and Production of Barley Irrigated with Saline Water in Salt-Affected Soil. Plants 2022, 11, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.R.; Haby, V.A. Simplified Colorimetric Determination of Soil Organic Matter. Soil Sci. 1971, 112, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansu, M.; Gautheyrou, J. Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; China Agricultural Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 25–97. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301822463_Soil_and_agricultural_chemistry_analysis (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, B. Comprehensive Assessments of Soil Fertility and Environmental Quality in Plastic Greenhouse Production Systems. Geoderma 2021, 385, 114899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamehpour, N.; Rezapour, S.; Ghaemian, N. Quantitative Assessment of Soil Quality Indices for Urban Croplands in a Calcareous Semi-Arid Ecosystem. Geoderma 2021, 382, 114781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masto, R.E.; Chhonkar, P.K.; Singh, D.; Patra, A.K. Alternative Soil Quality Indices for Evaluating the Effect of Intensive Cropping, Fertilisation and Manuring for 31 Years in the Semi-Arid Soils of India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2008, 136, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morag, J.; Dishon, M.; Sivan, U. The Governing Role of Surface Hydration in Ion Specific Adsorption to Silica: An AFM-Based Account of the Hofmeister Universality and Its Reversal. Langmuir 2013, 29, 6317–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rengasamy, P. Soil Processes Affecting Crop Production in Salt-affected Soils. Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, D. Chemical Interactions of Citrate, Calcium and Phosphate in a Calcareous Saskatchewan Subsoil. 2018. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/CHEMICAL-INTERACTIONS-OF-CITRATE%2C-CALCIUM-AND-IN-A-Bulmer/1b79cc449063d86ed0891dd2099c8d0658e66ad7 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; Xiao, J.; Chen, G. Combined Application of Humic Acid and Attapulgite Improves Physical Structure and Nutrients in Coastal Saline-Alkali Soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 4415–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chang, H.; Dong, Z.; Ren, Y.; Tan, T.; Deng, H. Dephenolization Pyrolysis Fluid Improved Physicochemical Properties and Microbial Community Structure of Saline-alkali Soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 20223–20234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.D.; Wang, H.J.; Zhong, M.T.; Song, J.H.; Shi, X.Y.; Tian, T.; Wang, J.G.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Jiang, M.H. Effects Of Straw Return and Biochar Application on Soil Nutrients and Osmotic Regulation in Cotton under Different Soil Salinity Levels. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2023, 21, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Nie, Z.; Zhou, J.; An, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Tóth, T.; Yang, F.; Wang, Z. Effects of Organic Amendments on Soil Bacterial Community Structure and Yield in a Saline-Sodic soil Cropped with Rice. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 5514–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Silva, E.; Alleoni, L.; Grazziotti, P. Citric Acid Influence on Soil Phosphorus Availability. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 2138–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, T.; Madhusha, C.; Munaweera, I.; Kottegoda, N. Review on Mechanisms of Phosphate Solubilization in Rock Phosphate Fertilizer. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 53, 944–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Schmidhalter, U. Drought and Salinity: A Comparison of Their Effects on Mineral Nutrition of Plants. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, L.F.; Schneider, R.; Cherubin, M.R.; Colares, G.S.; Wiesel, P.G.; da Costa, A.B.; Lobo, E.A. Development of a Soil Quality Index to Evaluate Agricultural Cropping Systems in Southern Brazil. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 218, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasu, D.; Tiwary, P.; Chandran, P. A Novel and Comprehensive Soil Quality Index Integrating Soil Morphological, Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 244, 106246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Liu, J.; Tang, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, S.; Tang, X.; Ding, Z.; Ma, M.; Ci, E. Establishing a Soil Quality Index to Evaluate Soil Quality after Afforestation in a Karst Region of Southwest China. CATENA 2023, 230, 107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M. Application of Soil Quality Index to Determine the Effects of Different Vegetation Types on Soil Quality in the Yellow River Delta wetland. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SOM (g kg−1) | AN (mg kg−1) | AP (mg kg−1) | AK (mg kg−1) | pH | EC (Us/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.72 | 71.4 | 17.21 | 140.29 | 8.81 | 155.6 |

| Treatments | Citric Acid (kg ha−1) | Nano-Silica (kg ha−1) | Humic Acid (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CS | 1875 | 1125 | 0 |

| CSH | 1875 | 1125 | 3000 |

| SH | 0 | 1125 | 3000 |

| CH | 1875 | 0 | 3000 |

| Treatments | Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | CO32− | HCO3− | Cl− | SO42− | Ex-Na+ | Ex-K+ | Ex-Ca2+ | Ex-Mg2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 7.66 ± 1.68 a | 0.19 ± 0.14 a | 2.08 ± 0.32 a | 0.59 ± 0.08 a | 2.67 ± 0.55 a | 2.82 ± 0.23 a | 0.13 ± 0.02 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 3.70 ± 0.50 a | 0.56 ± 0.16 a | 13.57 ± 2.20 c | 6.51 ± 0.96 a |

| CS | 4.36 ± 1.68 b | 0.12 ± 0.1 a | 2.14 ± 0.22 a | 0.45 ± 0.03 b | 1.39 ± 0.42 b | 2.16 ± 0.13 bc | 0.15 ± 0.04 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 2.03 ± 0.60 c | 0.64 ± 0.07 a | 17.26 ± 0.84 b | 5.40 ± 0.81 a |

| CSH | 3.63 ± 0.63 b | 0.19 ± 0.14 a | 3.4 ± 0.94 a | 0.44 ± 0.06 b | 1.21 ± 0.16 b | 1.73 ± 0.1 d | 0.16 ± 0.04 a | 0.24 ± 0.02 a | 1.09 ± 0.29 d | 0.81 ± 0.10 a | 20.00 ± 0.34 a | 6.48 ± 1.52 a |

| SH | 3.26 ± 0.63 b | 0.13 ± 0.06 a | 2.5 ± 0.05 a | 0.45 ± 0.09 b | 1.12 ± 0.16 b | 2.27 ± 0.1 b | 0.24 ± 0.19 a | 0.32 ± 0.11 a | 2.75 ± 0.17 b | 0.75 ± 0.04 a | 17.82 ± 1.51 ab | 6.48 ± 1.35 a |

| CH | 5.66 ± 1.65 ab | 0.19 ± 0.04 a | 2.53 ± 0.45 a | 0.59 ± 0.07 a | 1.76 ± 0.42 b | 1.94 ± 0.06 cd | 0.14 ± 0.04 a | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 1.16 ± 0.23 d | 0.71 ± 0.10 a | 18.25 ± 0.70 ab | 4.60 ± 1.93 a |

| EC | SAR | ESP | CEC | TA | Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | CO32− | HCO3− | Cl− | SO42− | Ex-Na+ | Ex-K+ | Ex-Ca2+ | Ex-Mg2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 0.375 | 0.449 | 0.567 * | −0.455 | 0.581 * | 0.355 | 0.015 | −0.472 | −0.052 | 0.408 | 0.757 ** | −0.273 | 0.259 | 0.754 ** | −0.402 | −0.646 ** | 0.456 |

| EC | 0.753 ** | 0.557 * | −0.318 | 0.723 ** | 0.737 ** | −0.044 | −0.220 | 0.244 | 0.729 ** | 0.570 * | −0.147 | −0.344 | 0.459 | −0.434 | −0.580 * | 0.001 | |

| SAR | 0.774 ** | −0.458 | 0.939 ** | 0.957 ** | 0.211 | −0.552 * | 0.550 * | 0.952 ** | 0.731 ** | −0.273 | −0.323 | 0.597 * | −0.575 * | −0.613 * | −0.183 | ||

| ESP | −0.568 * | 0.836 ** | 0.723 ** | 0.225 | −0.466 | 0.316 | 0.721 ** | 0.866 ** | 0.051 | −0.281 | 0.852 ** | −0.416 | −0.590 * | 0.109 | |||

| CEC | −0.496 | −0.386 | −0.084 | 0.716 ** | −0.11 | −0.359 | −0.629 * | 0.037 | 0.325 | −0.564 * | 0.593 * | 0.740 ** | 0.277 | ||||

| TA | 0.833 ** | 0.258 | −0.483 | 0.593 * | 0.957 ** | 0.874 ** | −0.194 | −0.293 | 0.768 ** | −0.524 * | −0.680 ** | 0.037 | |||||

| Na+ | 0.094 | −0.474 | 0.479 | 0.853 ** | 0.634 * | −0.307 | −0.314 | 0.503 | −0.625 * | −0.571 * | −0.261 | ||||||

| K+ | 0.021 | 0.466 | 0.346 | 0.057 | −0.055 | −0.277 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.182 | 0.161 | |||||||

| Ca2+ | −0.099 | −0.392 | −0.540 * | −0.011 | 0.028 | −0.46 | 0.528 * | 0.558 * | 0.413 | ||||||||

| Mg2+ | 0.650 ** | 0.381 | 0.004 | −0.266 | 0.249 | −0.159 | −0.193 | −0.145 | |||||||||

| CO32− | 0.697 ** | −0.271 | −0.337 | 0.568 * | −0.442 | −0.542 * | −0.048 | ||||||||||

| HCO3− | −0.025 | −0.16 | 0.952 ** | −0.559 * | −0.777 ** | 0.171 | |||||||||||

| Cl− | 0.028 | 0.075 | 0.339 | 0.267 | −0.094 | ||||||||||||

| SO42− | 0.003 | 0.146 | 0.206 | 0.307 | |||||||||||||

| Ex-Na+ | −0.517 * | −0.676 ** | 0.282 | ||||||||||||||

| Ex-K+ | 0.786 ** | 0.285 | |||||||||||||||

| Ex-Ca2+ | −0.032 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Zhou, L.; Lv, Q.; Ma, X. A Novel Composite Amendment for Soda Saline–Alkali Soils: Reducing Alkalinity, Enhancing Nutrient Content, and Increasing Maize Yield. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2910. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122910

Zhang C, Zhou L, Lv Q, Ma X. A Novel Composite Amendment for Soda Saline–Alkali Soils: Reducing Alkalinity, Enhancing Nutrient Content, and Increasing Maize Yield. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2910. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122910

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Can, Liqian Zhou, Qing Lv, and Xianfa Ma. 2025. "A Novel Composite Amendment for Soda Saline–Alkali Soils: Reducing Alkalinity, Enhancing Nutrient Content, and Increasing Maize Yield" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2910. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122910

APA StyleZhang, C., Zhou, L., Lv, Q., & Ma, X. (2025). A Novel Composite Amendment for Soda Saline–Alkali Soils: Reducing Alkalinity, Enhancing Nutrient Content, and Increasing Maize Yield. Agronomy, 15(12), 2910. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122910