Enhancing Soil Biological Health in a Rice–Wheat Cropping Sequence Using Rock Phosphate-Enriched Compost and Microbial Inoculants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of Rock Phosphate Enriched Compost

2.2. Inoculum Procurement and Application

2.3. Experimental Design and Site Description

2.4. Soil Analysis

2.5. Analysis of Post-Harvest Soil for Microbial Parameters

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Organic C and Microbial Biomass Nutrients

3.2. Soil Enzymatic Activities and Microbial Population

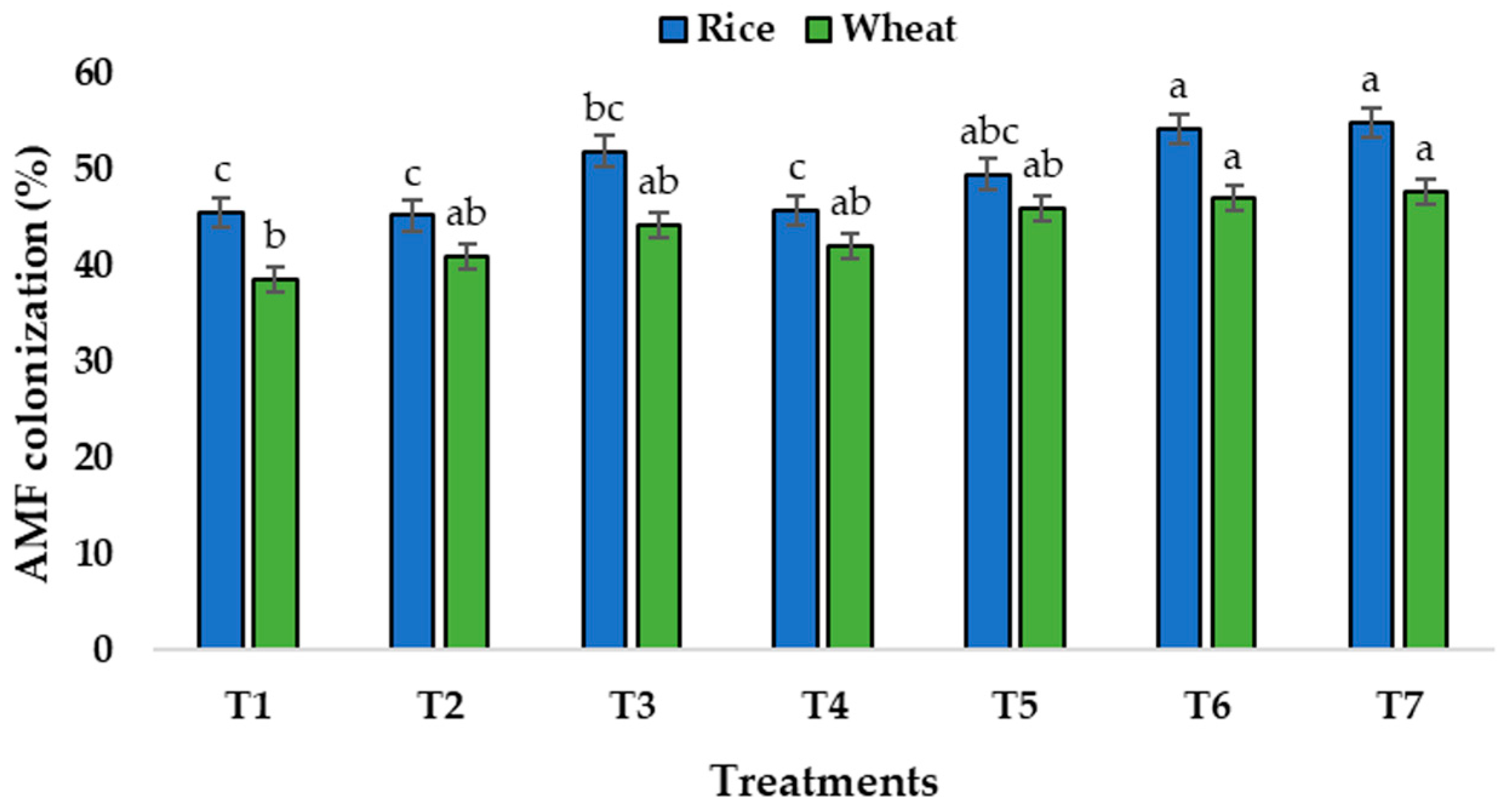

3.3. Root Colonization by AMF

3.4. Microbial Activity and MBP over Control After the Harvest of Both Crops

3.5. Crop Yield and P Uptake

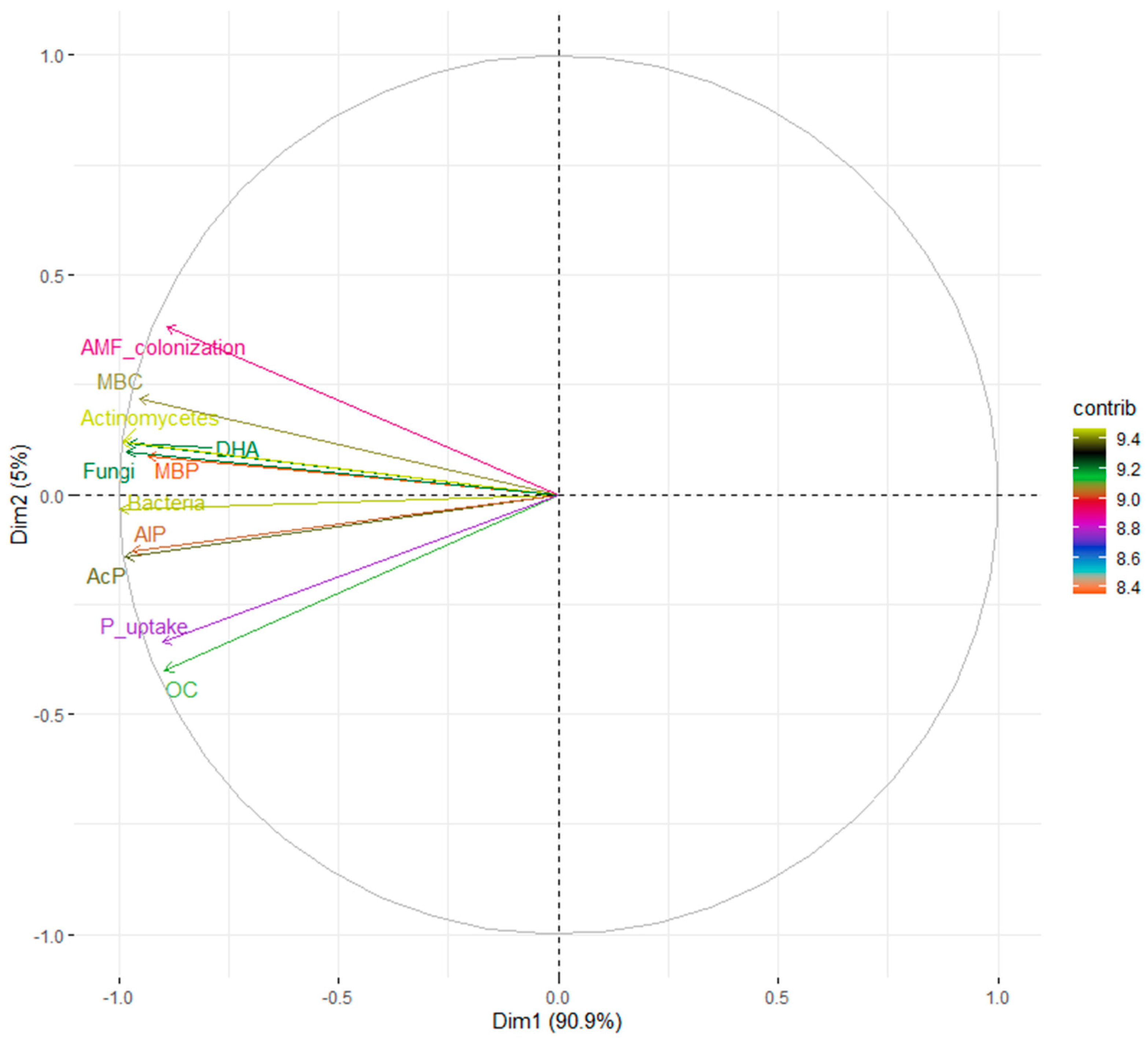

3.6. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pokharel, D.; Jha, R.K.; Tiwari, T.P.; Gathala, M.K.; Shrestha, H.K.; Panday, D. Is conservation agriculture a potential option for cereal-based sustainable farming system in the Eastern Indo-Gangetic Plains of Nepal? Cogent Food Agric. 2018, 4, 1557582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Mishra, R.P.; Shukla, A.K.; Timsina, J.; Upadhyay, P.K.; Shekhawat, K.; Majumdar, K.; Panwar, A.S. Yields, soil health and farm profits under a rice-wheat system: Long-term effect of fertilizers and organic manures applied alone and in combination. Agronomy 2018, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, P.; Jing, Y. Effects of long-term application of organic manure and chemical fertilizer on soil properties and microbial communities in the agro-pastoral ecotone of North China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 993973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Beura, K.; Pradhan, A.K.; Akhtar, S.; Ingle, S.N.; Das, S.P.; Behera, S.K.; Baranwal, D.K. Seed nutripriming and foliar application of phosphorus for enhanced nutrition in brinjal. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1632–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhya, S.S.; Sharma, S. Nanoscience and nanotechnology: Cracking prodigal farming. J. Bionanosci. 2013, 7, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, K.; Singh, M.; Pradhan, A.K.; Rakshit, R.; Lal, M. Dissolution of dominant soil phosphorus fractions in phosphorus-responsive soils of Bihar, India: Effects of mycorrhiza and fertilizer levels. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, K.S.; Ghosh, G.K.; Pradhan, A.K.; Kohli, A. Forms of phosphorus and its bioavailability in rice grown in an alluvial soil treated with rock phosphate enriched compost. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 1682–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, K.S.; Ghosh, G.K.; Pradhan, A.K.; Kohli, A.; Singh, M.; Shambhavi, S.; Kumar, S. Fractional release kinetics of phosphorus from compost amended with phosphate rock. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2021, 52, 1115–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, K.; Padbhushan, R.; Pradhan, A.K.; Mandal, N. Partial acidulation of phosphate rock for enhanced phosphorus availability in alluvial soils of Bihar, India. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2016, 8, 1393–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, C.H.; Condron, L.M.; Callaghan, M.O.; Stewart, A.; Di, H.J. Differences in soil enzyme activities, microbial community structure and short-term nitrogen mineralisation resulting from farm management history and organic matter amendments. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Piqueres, A.; Edel-Hermann, V.; Alabouvette, C.; Steinberg, C. Response of soil microbial communities to compost amendments. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, K.; Joergensen, R.G. Decomposition of 14C labelled glucose in a Pb-contaminated soil remediated with synthetic zeolite and other amendments. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Patra, A.K.; Singh, D.; Swarup, A.; Masto, R.E. Effect of long-term application of manure and fertilizer on biological and biochemical activities in soil during crop development stages. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 3585–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Kundu, S.; Prakash, V.; Gupta, H.S. Sustainability under combined application of mineral and organic fertilizers in a rain-fed soybean–wheat system of the Indian Himalayas. Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.; Khan, M.; Bano, A.; Nisa, S.; Hussain, A.; Dawar, K.M.; Munir, A.; Khan, N. Rock phosphate-enriched compost in combination with rhizobacteria; a cost-effective source for better soil health and wheat (Triticum aestivum) productivity. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; de-Bashan, L.E. How the plant growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum promotes plant growth—A critical assessment. Adv. Agron. 2010, 108, 77–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bending, G.D.; Turner, M.K.; Jones, J.E. Interactions between crop residue and soil organic matter quality and the functional diversity of soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, V.V.; Kalagudi, G.M. Enhancing plant phosphorus use efficiency for sustainable cropping. Biotechnol. Adv. 2005, 23, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.L.; Bian, W.; Zhu, J. Screening and identification of microorganisms capable of utilizing phosphate adsorbed by goethite. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2002, 33, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Singh, O.; Nayyar, H.; Kaur, J.; Tewari, R. Stimulatory effect of phosphate-solubilizing fungal strains (Aspergillus awamori and Penicillium citrinum) on the yield of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L. cv. GPF2). Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.L. Soil Chemical Analysis; Prentice Hall of India Pvt., Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1973; p. 498. [Google Scholar]

- Walkley, A.J.; Black, C.A. An estimation of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, B.V.; Asija, G.L. A rapid procedure for the estimation of available nitrogen in soils. Curr. Sci. 1956, 25, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Hanway, J.J.; Heidel, H. Soil analysis methods as used in Iowa State College soil testing laboratory. Iowa State Coll. Agric. Bull. 1952, 57, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, C.V.; Watanabe, F.S.; Dean, L.A. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954.

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Powlson, D.S. The effects of biocidal treatments on metabolism in soil—V: A method for measuring soil biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1976, 8, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Powlson, D.S.; Jenkinson, D.S. Measurement of microbial biomass phosphorus in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1982, 14, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.A.; Loh, T.C.; Goulding, R.L. A rapid procedure to evaluate dehydrogenase activity of soils low in organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1971, 3, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A.; Bremner, J.M. Use of p-nitrophenyl phosphate for assay of soil phosphatase activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1969, 1, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhonkar, P.K.; Bhadraray, S.; Patra, A.K.; Purakayastha, T.J. Experiments in Soil Biology and Biochemistry; Westville Publishing House: New Delhi, India, 2007; ISBN 978-8185873329. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, B.; Linderman, R.G. Quantifying vesicular–arbuscular mycorrhizae: A proposed method towards standardization. New Phytol. 1981, 87, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Kundu, M.; Das, A.; Rakshit, R.; Sahay, S.; Sengupta, S.; Ahmad, M.F. Long-term integrated nutrient management improves carbon stock and fruit yield in a subtropical mango (Mangifera indica L.) orchard. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.D.; Biswas, D.R. Changes in biological properties in soil amended with rock phosphate and waste mica enriched compost using biological amendments and chemical fertilizers under wheat–soybean rotation. J. Plant Nutr. 2014, 37, 2050–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhull, S.; Goyal, S.; Kapoor, K.; Mundra, M. Microbial biomass carbon and microbial activities of soils receiving chemical fertilizers and organic amendments. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2004, 50, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Mishra, M.M.; Hooda, I.S.; Singh, R. Organic matter–microbial biomass relationship in field experiments under tropical conditions: Effects of inorganic fertilization and organic amendments. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1992, 24, 1081–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberson, A.; Friesen, D.K.; Rao, I.M.; Buhler, S.; Frossard, E. Phosphorus transformations in an Oxisol under contrasting land-use systems: The role of the microbial biomass. Plant Soil 2001, 237, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Bano, A.; Zandi, P. Effects of exogenously applied plant growth regulators in combination with PGPR on the physiology and root growth of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and their role in drought tolerance. J. Plant Interact. 2018, 13, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaga, G.; Todd, A.; Brookes, P.C. Enhanced biological cycling of phosphorus increases its availability to crops in low-input sub-Saharan farming systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, P.; Biswas, D. Assessment of maturity indices of rock phosphate enriched composts using variable crop residues. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 222, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavagnaro, T.R.; Bender, S.F.; Asghari, H.R.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizas in reducing soil nutrient loss. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beura, K.; Pradhan, A.K.; Ghosh, G.K.; Kohli, A.; Singh, M. Root architecture, yield and phosphorus uptake by rice: Response to rock phosphate enriched compost and microbial inoculants. Int. Res. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Gu, S.; Xin, Y.; Bello, A.; Sun, W.; Xu, X. Compost addition enhanced hyphal growth and sporulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi without affecting their community composition in the soil. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Song, F.; Liu, S.; Liu, T.; Zhou, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizae improve photosynthesis and water status of Zea mays L. under drought stress. Plant Soil Environ. 2012, 58, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K.; Chauhan, A.; Verma, R.S.; Rahman, L.U.; Bisht, A. Improving production potential and resource use efficiency of peppermint (Mentha piperita L.) intercropped with geranium (Pelargonium graveolens L.) under different plant density. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, F.; Reheul, D. Permanent grassland and 3-year leys alternating with 3 years of arable land: 31 years of comparison. Eur. J. Agron. 2003, 19, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achal, V.; Savant, V.V.; Reddy, M.S. Phosphate solubilization by a wild type strain and UV-induced mutants of Aspergillus tubingensis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanth, D.; Biswas, D. Kinetics of phosphorus and potassium release from rock phosphate and waste mica enriched compost and their effect on yield and nutrient uptake by wheat (Triticum aestivum). Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3342–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beura, K.; Pradhan, A.; Ingle, S. Role of phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs) in sustainable crop production. Harit Dhara 2025, 8, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter (Unit) | Rock Phosphate | REC |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated Value | ||

| Bulk density (g cm−3) | 2.74 | 0.64 |

| Particle density (g cm−3) | - | 1.88 |

| Porosity (%) | - | 65.95 |

| Moisture percentage (%) | 3.16 | 39.72 |

| pH | 7.46 | 6.92 |

| Electrical conductivity (dS m−1) | 2.58 | 1.82 |

| Organic C (%) | ND | 19.80 |

| Cation exchange capacity [cmol (p+) kg−1)] | 12.07 | 176.02 |

| Total nitrogen (%) | 0.01 | 1.33 |

| Total phosphorous (%) | 10.86 | 2.67 |

| Water soluble phosphorous (%) | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Citric acid soluble phosphorous (%) | 0.05 | 1.43 |

| Citric acid insoluble phosphorous (%) | 10.81 | 1.22 |

| Total potassium (%) | 0.011 | 1.10 |

| Total calcium (%) | 6.70 | 3.14 |

| Total sulphur (%) | 0.44 | 0.57 |

| Total zinc (mg kg−1) | 154.83 | 179.88 |

| Total copper (mg kg−1) | 10.93 | 32.41 |

| Total iron (mg kg−1) | 981.83 | 1453.98 |

| Total manganese (mg kg−1) | 495.92 | 703.30 |

| Parameter | Estimated Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial population | Bacteria (×106 cfu g−1 dry soil) | 61.32 |

| Actinomycetes (×106 cfu g−1 dry soil) | 19.59 | |

| Fungi (×106 cfu g−1 dry soil) | 19.44 | |

| PSB (×106 cfu g−1 dry soil) | 14.26 | |

| Rhizobium (×106 cfu g−1 dry soil) | 41.74 | |

| Azotobacter (×106 cfu g−1 dry soil) | 12.27 | |

| Enzymatic activity | Dehydrogenase (TPF g−1 24 h−1) | 77.35 |

| Acid phosphatase (µg PNP g−1 soil h−1) | 83.71 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (µg PNP g−1 soil h−1) | 127.02 | |

| Microbial Biomass C (mg kg−1) | 513.76 | |

| C:N ratio | 14.89 | |

| Characteristics | Burkholderia cepacia |

|---|---|

| Colony type on nutrient Agar | Raised |

| Color | Yellowish |

| Gram reaction | −ve |

| Growth at pH 6.5 | Good |

| P solubilization from Ca3PO4 | 285.77 mg L−1 |

| P solubilization zone | 12.5 mm |

| H2S production | +ve |

| Texture | Mucoid |

| Opacity | Opaque |

| Sl. No. | Treatment Details |

|---|---|

| 1. | T1: Absolute control (no fertilization) |

| 2. | T2: 100% RDF |

| 3. | T3: REC at rate 100% of the RDP dose + PSB + AMF |

| 4. | T4: 50% RDP + REC at rate 50% of the RDP dose |

| 5. | T5: 50% RDP + REC at rate 50% of the RDP dose + PSB |

| 6. | T6: 50% RDP + REC at rate 50% of the RDP dose + AMF |

| 7. | T7: 50% RDP + REC at rate 50% of the RDP dose + PSB + AMF |

| Treatment | Organic C (g kg−1) | MBC (mg kg−1) | MBP (mg kg−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | |

| T1 | 5.56 c | 5.49 c | 250.6 e | 246.9 e | 9.7 b | 10.2 c |

| T2 | 5.59 b | 5.58 b | 280.7 d | 283.8 d | 10.9 b | 11.5 c |

| T3 | 5.63 a | 5.65 a | 306.7 c | 314.9 c | 17.9 a | 18.9 b |

| T4 | 5.63 a | 5.64 a | 318.4 c | 320.6 c | 21.4 a | 22.3 ab |

| T5 | 5.64 a | 5.65 a | 354.8 b | 369.8 b | 22.4 a | 23.4 ab |

| T6 | 5.64 a | 5.65 a | 361.0 b | 373.3 b | 22.4 a | 23.7 ab |

| T7 | 5.66 a | 5.67 a | 425.6 a | 430.2 a | 22.5 a | 23.9 a |

| SEm (±) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Treatment | Dehydrogenase Activity (TPF g−1 24 h−1) | Acid Phosphatase Activity (µg PNP g−1 Soil h−1) | Alkaline Phosphatase Activity (µg PNP g−1 Soil h−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | |

| T1 | 18.6 e | 19.3 f | 25.1 e | 25.7 d | 129.2 e | 130.8 e |

| T2 | 28.9 d | 29.5 e | 36.2 d | 36.7 c | 150.7 d | 151.8 d |

| T3 | 31.5 d | 32.3 de | 37.5 cd | 38.7 bc | 159.4 cd | 160.5 cd |

| T4 | 36.5 c | 37.3 cd | 38.6 bcd | 39.3 bc | 174.1 ab | 175.3 ab |

| T5 | 48.2 a | 49.1 a | 42.3 ab | 43.3 ab | 176.9 ab | 177.6 ab |

| T6 | 48.3 a | 49.3 a | 43.4 a | 44.2 a | 175.8 ab | 176.5 ab |

| T7 | 51.6 a | 51.9 a | 44.9 a | 45.9 a | 178.2 a | 179.1 a |

| SEm (±) | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| Treatment | Bacteria (cfu × 10−6) | Actinomycetes (cfu × 10−6) | Fungi (cfu × 10−4) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | |

| T1 | 17.9 d | 19.2 e | 12.3 e | 13.8 e | 13.6 d | 14.9 e |

| T2 | 28.3 c | 30.2 d | 18.0 d | 18.7 d | 17.9 c | 19.1 d |

| T3 | 33.9 b | 34.8 c | 22.8 c | 24.1 c | 23.2 b | 25.6 bc |

| T4 | 36.5 b | 38.0 b | 24.1 c | 25.6 c | 24.9 b | 26.7 b |

| T5 | 39.9 ab | 41.7 ab | 28.9 ab | 29.7 b | 26.8 b | 27.1 b |

| T6 | 40.7 a | 44.6 a | 29.8 a | 31.1 ab | 28.4 ab | 29.6 b |

| T7 | 43.8 a | 46.9 a | 32.9 a | 34.2 a | 31.7 a | 33.7 a |

| SEm (±) | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Treatment | Grain Yield (q ha−1) | Grain P Uptake (kg ha−1) | Straw Yield (q ha−1) | Straw P Uptake (kg ha−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | Rice | Wheat | |

| T1 | 28.1 b | 24.7 c | 5.6 c | 8.7 c | 39.2 b | 34.6 c | 4.8 c | 1.5 c |

| T2 | 42.0 a | 47.3 a | 11.3 ab | 16.9 ab | 58.8 a | 66.3 a | 9.3 ab | 2.8 ab |

| T3 | 39.3 b | 38.1 b | 10.1 b | 13.7 b | 55.1 a | 53.3 b | 6.7 bc | 2.2 b |

| T4 | 43.3 a | 47.1 a | 11.3 ab | 17.4 a | 60.7 a | 65.9 a | 8.6 abc | 2.9 ab |

| T5 | 45.0 a | 48.5 a | 11.8 ab | 17.9 a | 63.0 a | 67.8 a | 9.6 ab | 2.9 ab |

| T6 | 45.0 a | 49.1 a | 11.8 ab | 18.3 a | 63.0 a | 68.7 a | 9.5 ab | 2.9 ab |

| T7 | 48.7 a | 50.3 a | 13.8 a | 18.7 a | 68.1 a | 70.4 a | 11.1 a | 3.1 a |

| SEm (±) | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beura, K.; Pradhan, A.K.; Ingle, S.N.; Kohli, A.; Ghosh, G.K.; Singh, M.; Behera, S.K.; Panday, D. Enhancing Soil Biological Health in a Rice–Wheat Cropping Sequence Using Rock Phosphate-Enriched Compost and Microbial Inoculants. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2911. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122911

Beura K, Pradhan AK, Ingle SN, Kohli A, Ghosh GK, Singh M, Behera SK, Panday D. Enhancing Soil Biological Health in a Rice–Wheat Cropping Sequence Using Rock Phosphate-Enriched Compost and Microbial Inoculants. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2911. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122911

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeura, Kasturikasen, Amit Kumar Pradhan, Sagar Nandulal Ingle, Anshuman Kohli, Goutam Kumar Ghosh, Mahendra Singh, Subrat Keshori Behera, and Dinesh Panday. 2025. "Enhancing Soil Biological Health in a Rice–Wheat Cropping Sequence Using Rock Phosphate-Enriched Compost and Microbial Inoculants" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2911. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122911

APA StyleBeura, K., Pradhan, A. K., Ingle, S. N., Kohli, A., Ghosh, G. K., Singh, M., Behera, S. K., & Panday, D. (2025). Enhancing Soil Biological Health in a Rice–Wheat Cropping Sequence Using Rock Phosphate-Enriched Compost and Microbial Inoculants. Agronomy, 15(12), 2911. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122911