Effect of Soil Treatments with Vermicompost and Ag+ on Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Inoculated with the Leaf Nematode Aphelenchoides Fragariae

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Design

- (1)

- Control (soil without any amendment applied)

- (2)

- 30 L of vermicompost (with 150–200 specimens of Eisenia fetida)

- (3)

- 1 L of solutions of Ag-NPs (dose 60 mg per 1 L soil)

- -

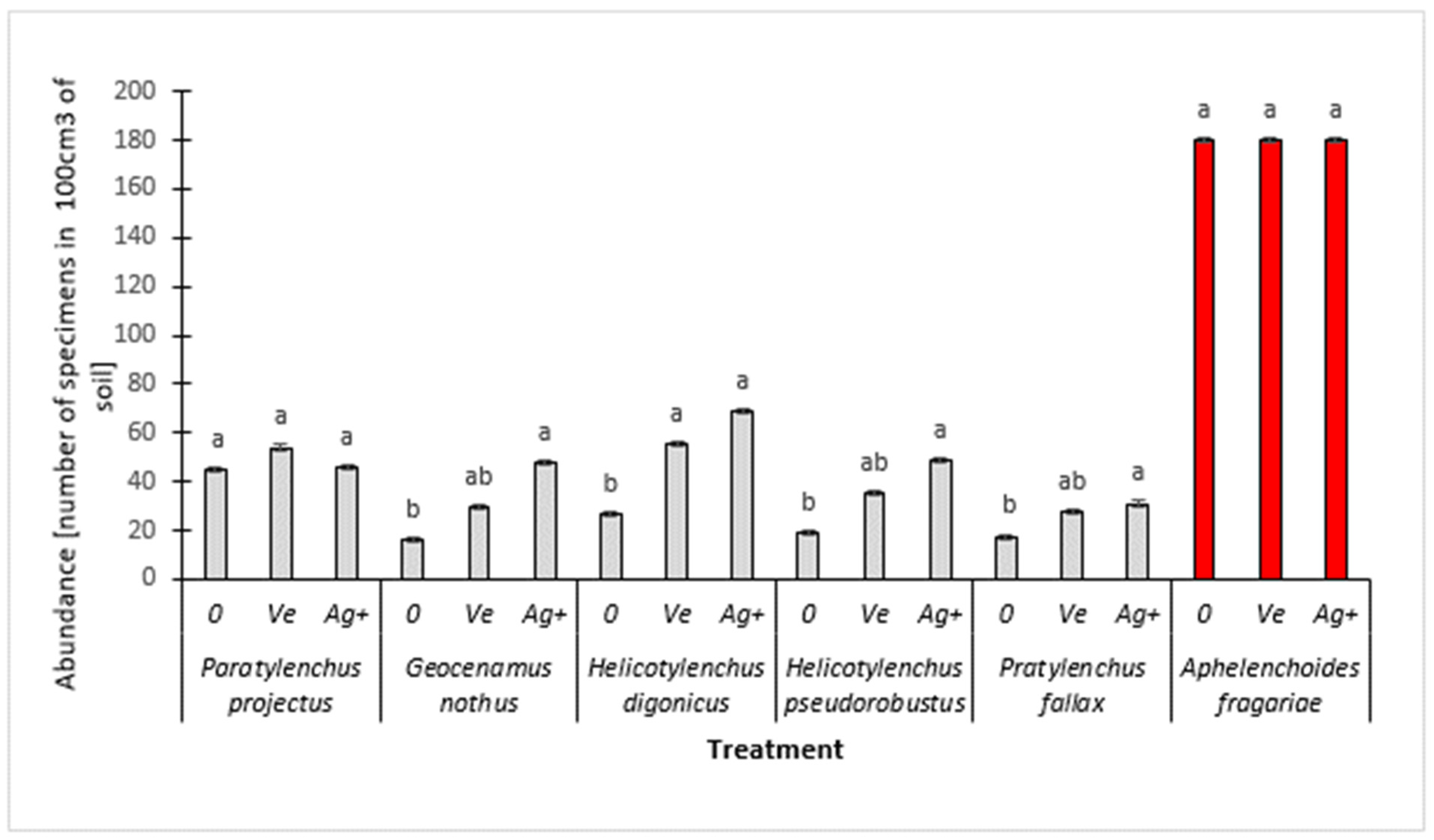

- Migratory endoparasites and foliar nematodes: Pratylenchus projectus (49 individuals), Pratylenchus fallax (17 individuals)

- -

- Semi-endoparasites: Helicotylenchus digonicus, (27 individuals), Helicotylenchus pseudorobustus (19 individuals)

- -

- Migratory ectoparasites: Geocenamus nothus (15 individuals)

2.2. Soil Analysis

2.3. Nematode Isolation and Analysis

2.4. Biometric Characteristics of Plants

2.5. Strawberry Yield Assessment

- 2022: 18 June, 22 June, 26 June, 30 June, 3 July, 7 July, 11 July

- 2023: 19 June, 23 June, 27 June, 1 July, 5 July, 9 July, 13 July

2.6. Statistical Analysis

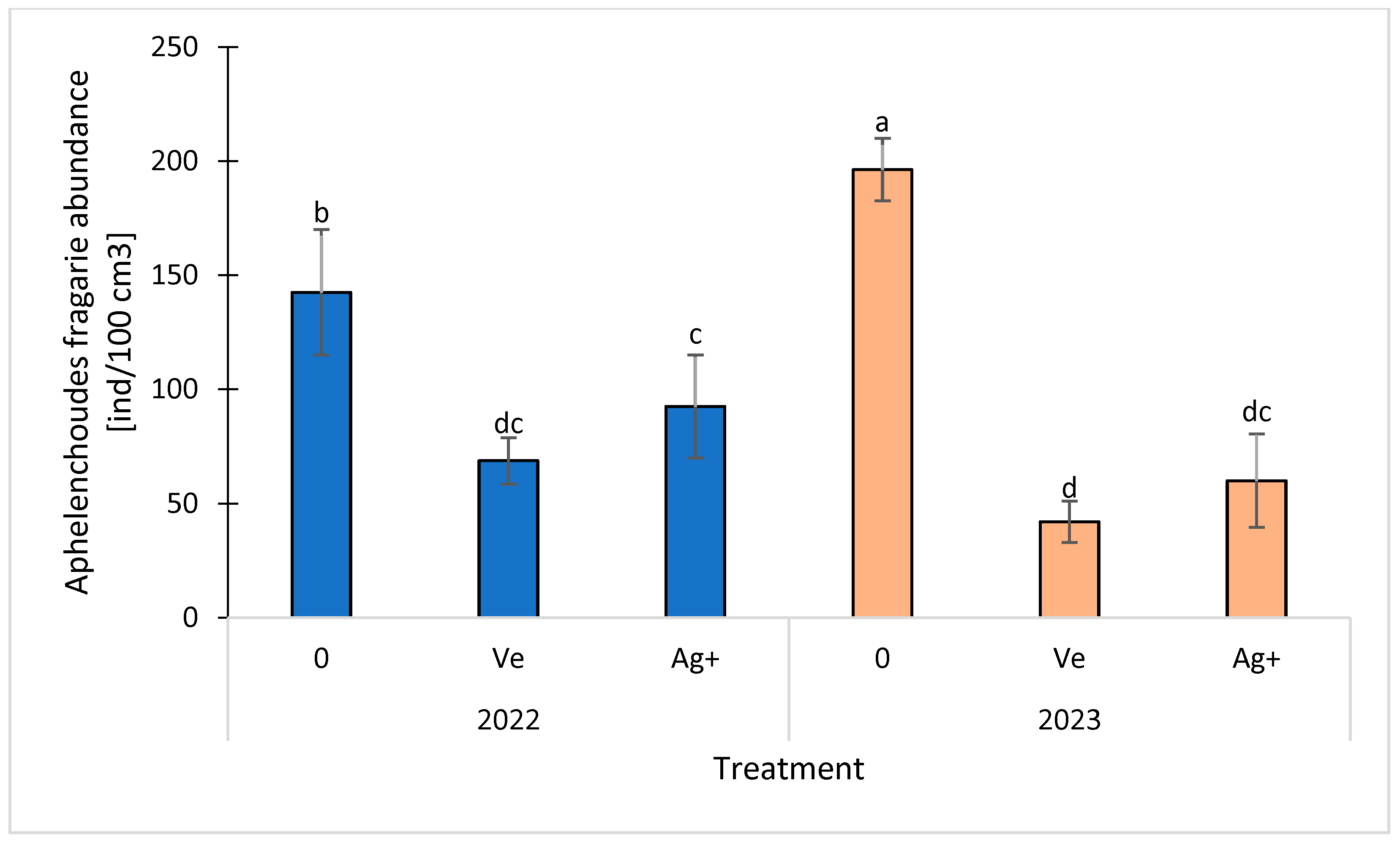

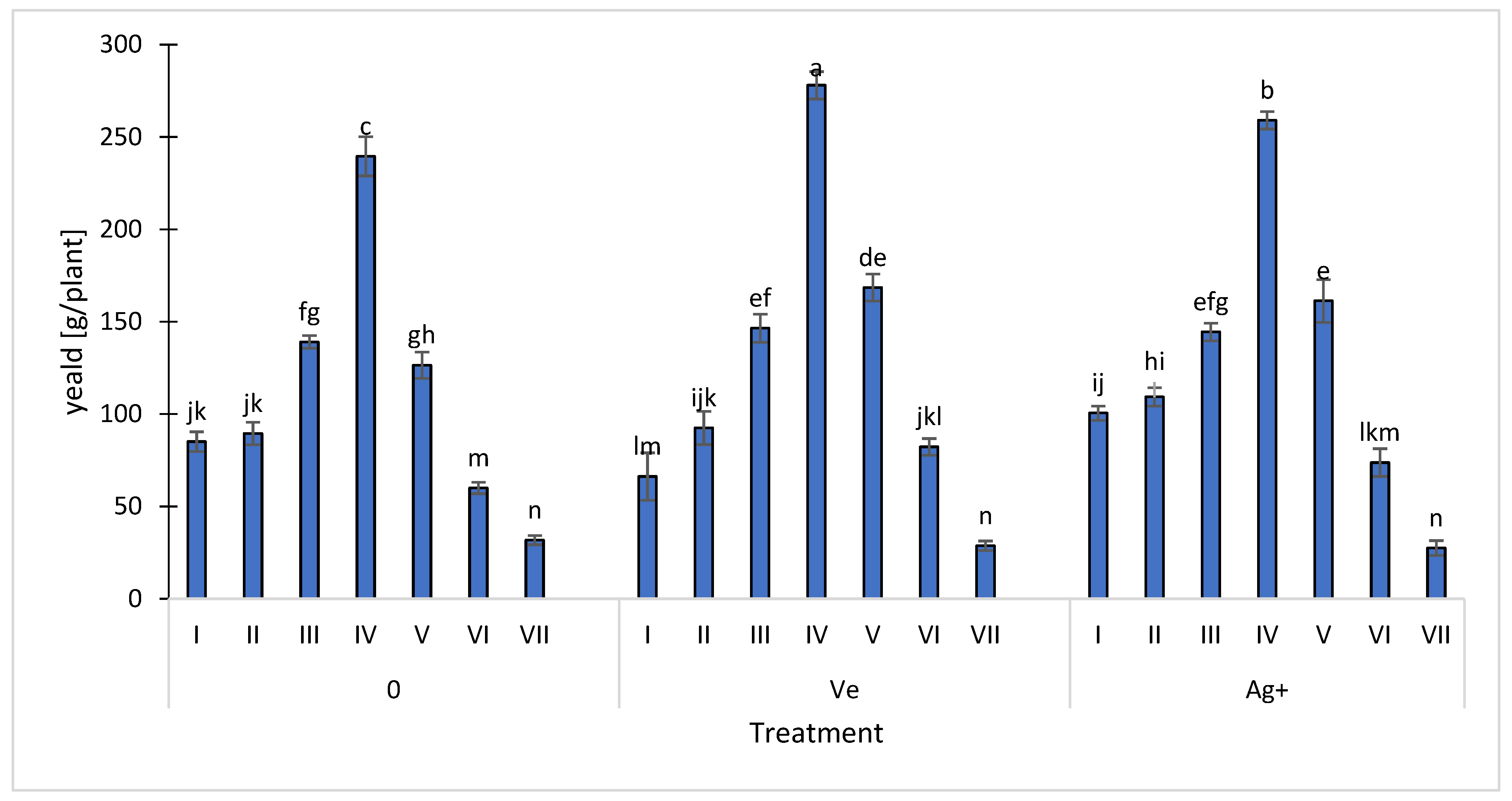

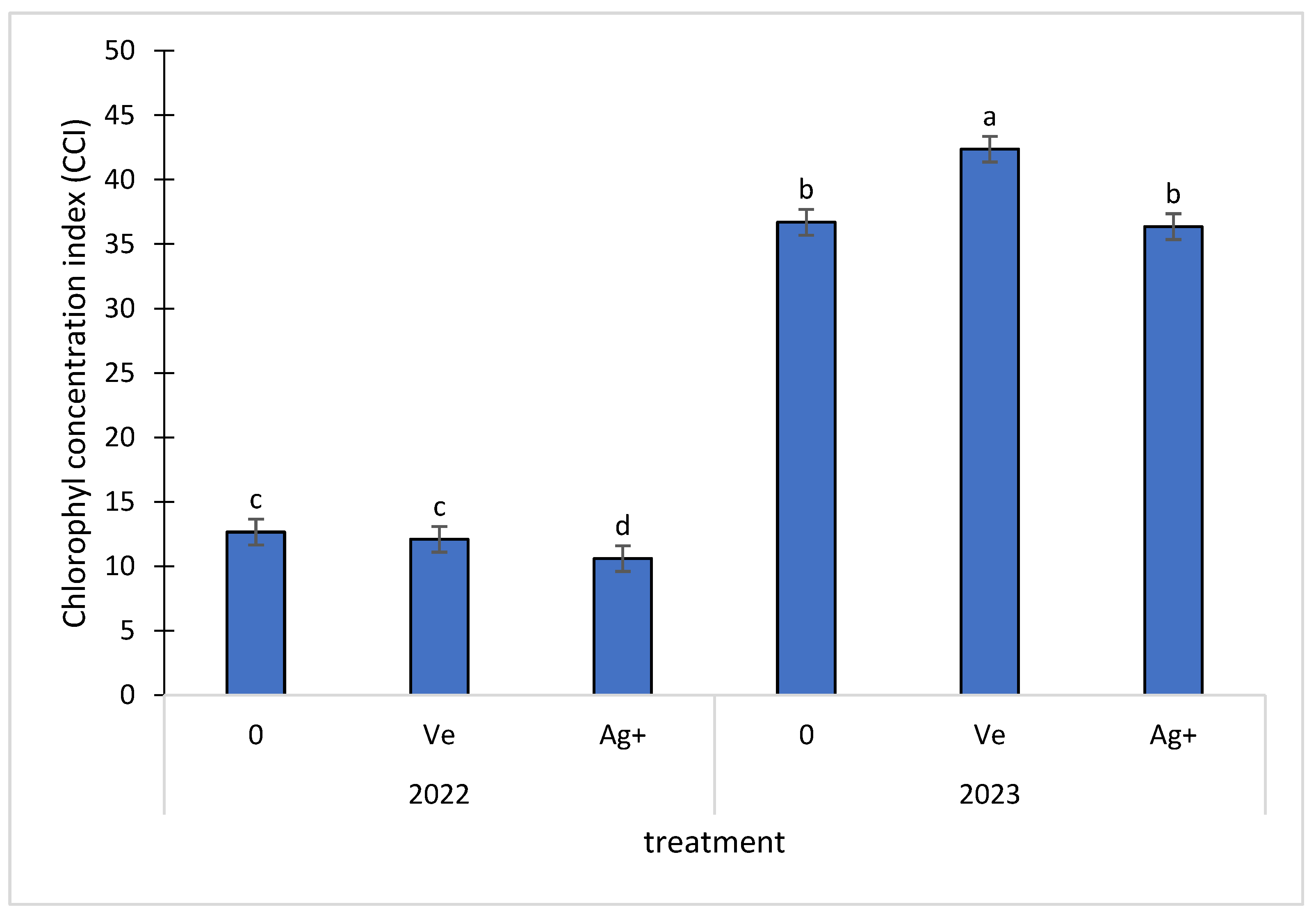

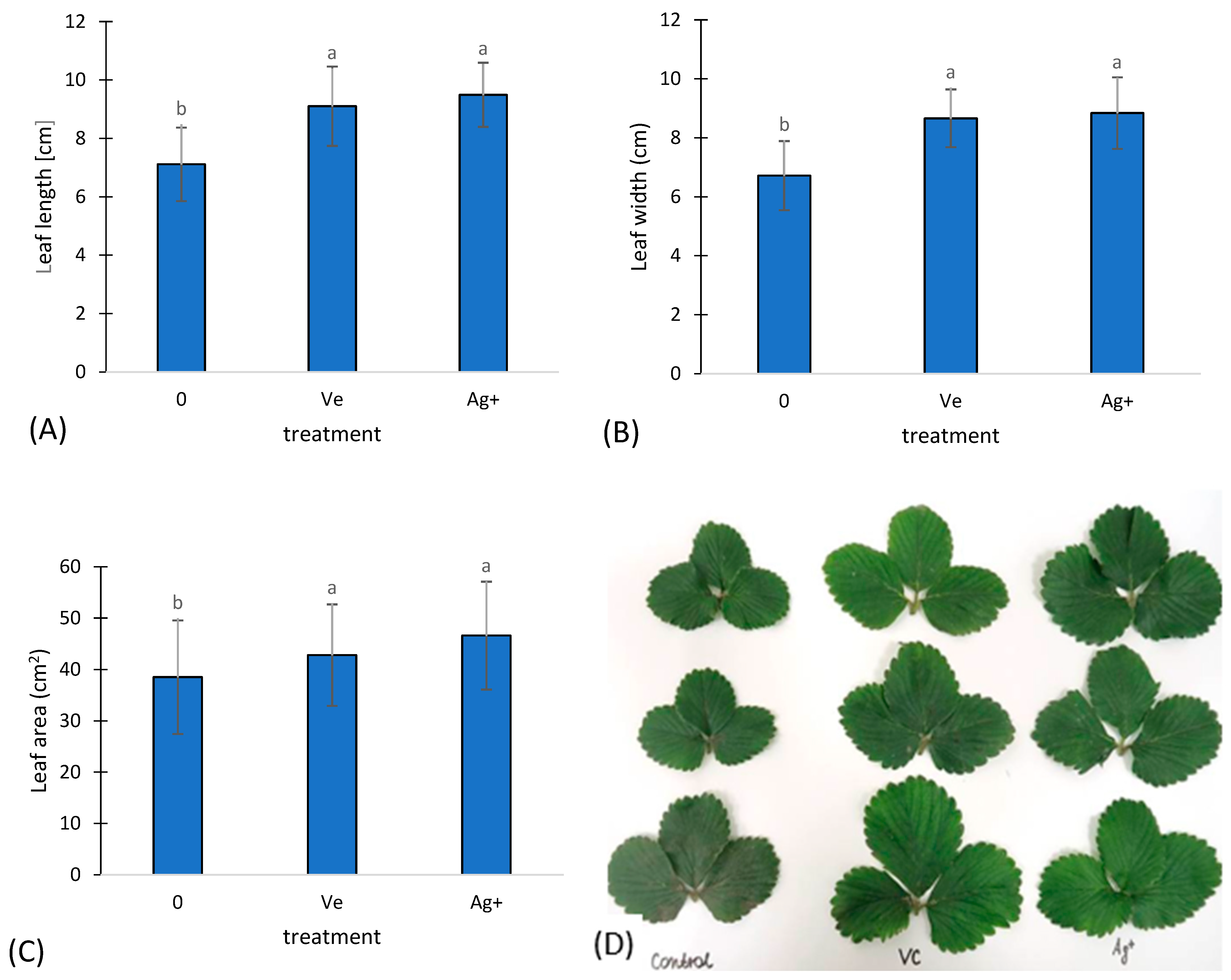

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krajowy Ośrodek Wsparcia Rolnictwa (KOWR). Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/kowr/polska-wsrod-liderow-produkcji-truskawek-w-ue (accessed on 22 July 2025). (In Polish)

- Wójcik, D.; Markiewicz, M.; Matysiak, B.; Sowik, I. Effect of LED light irradiation on morphology, chlorophyll content and photosynthetic activity of strawberry (Fragaria x ananasa Duch.) cuttings. Sci. J. Inst. Hortic. 2021, 29, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, S.; Smith, H.A.; Gireesh, M.; Kaur, G.; Montemayor, J.D. Arthropod Pest Management in Strawberry. Insects 2022, 13, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmanczyk, E.M.; Kozacki, D.; Ourry, M.; Bickel, S.; Olimi, E.; Masquelier, S.; Turci, S.; Bohr, A.; Maisel, H.; D’Avino, L.; et al. An Analysis of Soil Nematode Communities Across Diverse Horticultural Cropping Systems. Soil. Syst. 2025, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elgawad, M.M.M. Plant-parasitic nematodes of strawberry in Egypt: A review. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaliev, H.Y.; Mohamedova, M. Plant-parasitic nematodes associated with strawberry (Fragaria aiianassa Duch.) in Bulgaria. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. Agric. Acad. 2011, 17, 730–735. [Google Scholar]

- Nyoike, T.W.; Mekete, T.; McSorley, R.; Weibelzahl-Karigi, E.; Liburd, O.E. Confirmation of Meloidogyne hapla on strawberry in Florida using molecular and morphological techniques. Nematropica 2012, 42, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Nematode Problems on Strawberries. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/nematode-problems-on-strawberries (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Subbotin, S.A. Rapid Detection of the Strawberry Foliar Nematode Aphelenchoides fragariae Using Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Assay with Lateral Flow Dipsticks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przemieniecki, S.W.; Zapałowska, A.; Skwiercz, A.; Damszel, M.; Telesiński, A.; Sierota, Z.; Gorczyca, A. An evaluation of selected chemical, biochemical, and biological parameters of soil enriched with vermicompost. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8117–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapałowska, A.; Skwiercz, A.; Puchalski, C.; Malewski, T. Influence of Eisenia fetida on the Nematode Populations During Vermicomposting Process. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Jung, J.H.; Lamsal, K.; Kim, Y.S.; Min, J.S.; Lee, Y.S. Antifungal Effects of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) Against Various Plant Pathogenic Fungi. Mycobiology 2012, 1, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Zahoor, M.; Khan, R.S.; Ikram, M.; Islam, N.U. The impact of silver nanoparticles on the growth of plants: The agriculture applications. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasule, D.L.; Shingote, P.R.; Saxena, S. Exploitation of functionalized green nanomaterials for plant disease management. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfosea-Simón, F.J.; Burgos, L.; Alburquerque, N. Silver Nanoparticles Help Plants Grow, Alleviate Stresses, and Fight Against Pathogens. Plants 2025, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, F.; Da Silva, S.; Massironi, A.; Mirpoor, S.F.; Lignou, S.; Ghawi, S.K.; Charalampopoulos, D. Advancing Food Preservation: Sustainable Green-AgNPs Bionanocomposites in Paper-Starch Flexible Packaging for Prolonged Shelf Life. Polymers 2024, 16, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemail, M.M.; Elesawi, I.E.; Jghef, M.M.; Alharthi, B.; Alsanei, W.A.; Chen, C.; El-Hefnawi, S.M.; Gad, M.M. Influence of Wax and Silver Nanoparticles on Preservation Quality of Murcott Mandarin Fruit During Cold Storage and after Shelf-Life. Coatings 2023, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaegi, R.; Voegelin, A.; Sinnet, B.; Hagendorfer, H.; Burkhardt, M.; Siegrist, H. Behavior of metallic silver nanoparticles in a pilot wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3902–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Levard, C.; Judy, J.D.; Unrine, J.M.; Durenkamp, M.; Martin, B.; Jefferson, B.; Lowry, G.V. Fate of zinc oxide and silver nanoparticles in a pilot wastewater treatment plant and in processed biosolids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levard, C.; Hotze, E.M.; Lowry, G.V.; Brown, G.E. Environmental transformations of silver nanoparticles: Impact on stability and toxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6900–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chałańska, A.; Łabanowski, G.S.; Malewski, T. Diagnostyka Nicieni Liściowych z Rodzaju Aphelenchoides; Instytut Sadownictwa i Kwiaciarstwa (ISiK): Skierniewice, Poland, 2010; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://files.isric.org/public/documents/WRB_fourth_edition_2022-12-18.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Nowosielski, O. Zasady Opracowywania Zaleceń Nawozowych w Ogrodnictwie, Wyd. III ed; PWRiL: Warszawa, Poland, 1988; p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Komosa, A.; Breś, W.; Golcz, A.; Kozik, E. Żywienie Roślin Ogrodniczych—Podstawy i Perspektywy; PWRiL: Poznań, Poland, 2012; p. 390. Available online: https://www.agroswiat.pl/zywienie-roslin-ogrodniczych-11920.html (accessed on 22 July 2025). (In Polish)

- Ostrowska, A.; Gawliński, S.; Szczubiałka, Z. Metody Analizy i Oceny Właściwości Gleb i Roślin; Instytut Ochrony Środowiska: Warszawa, Poland, 1991; p. 334. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1394461 (accessed on 22 July 2025). (In Polish).

- Antweiler, R.C.; Patton, C.J.; Taylor, H.E. Automated Colorimetric Methods for Determination Nitrate Plus Nitrite, Nitrite, Ammonium and Orthophosphate Ions in Natural Wather Samples; Open-File Report 93–638, Denver, Colorado, 1–23; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Zawadzińska, A.; Salachna, P.; Nowak, J.S.; Kowalczyk, W.; Piechocki, R.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Pietrak, A. Compost Based on Pulp and Paper Mill Sludge, Fruit-Vegetable Waste, Mushroom Spent Substrate and Rye Straw Improves Yield and Nutritional Value of Tomato. Agronomy 2022, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Dated 5 June 2019. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Stefanovska, T.; Skwiercz, A.; Pidlisnyuk, V.; Zhukov, O.; Kozacki, D.; Mamirova, A.; Newton, R.A.; Ust’ak, S. The Short-Term Effects of Amendments on Nematode Communities and Diversity Patterns Under the Cultivation of Miscanthus × giganteus on Marginal Land. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

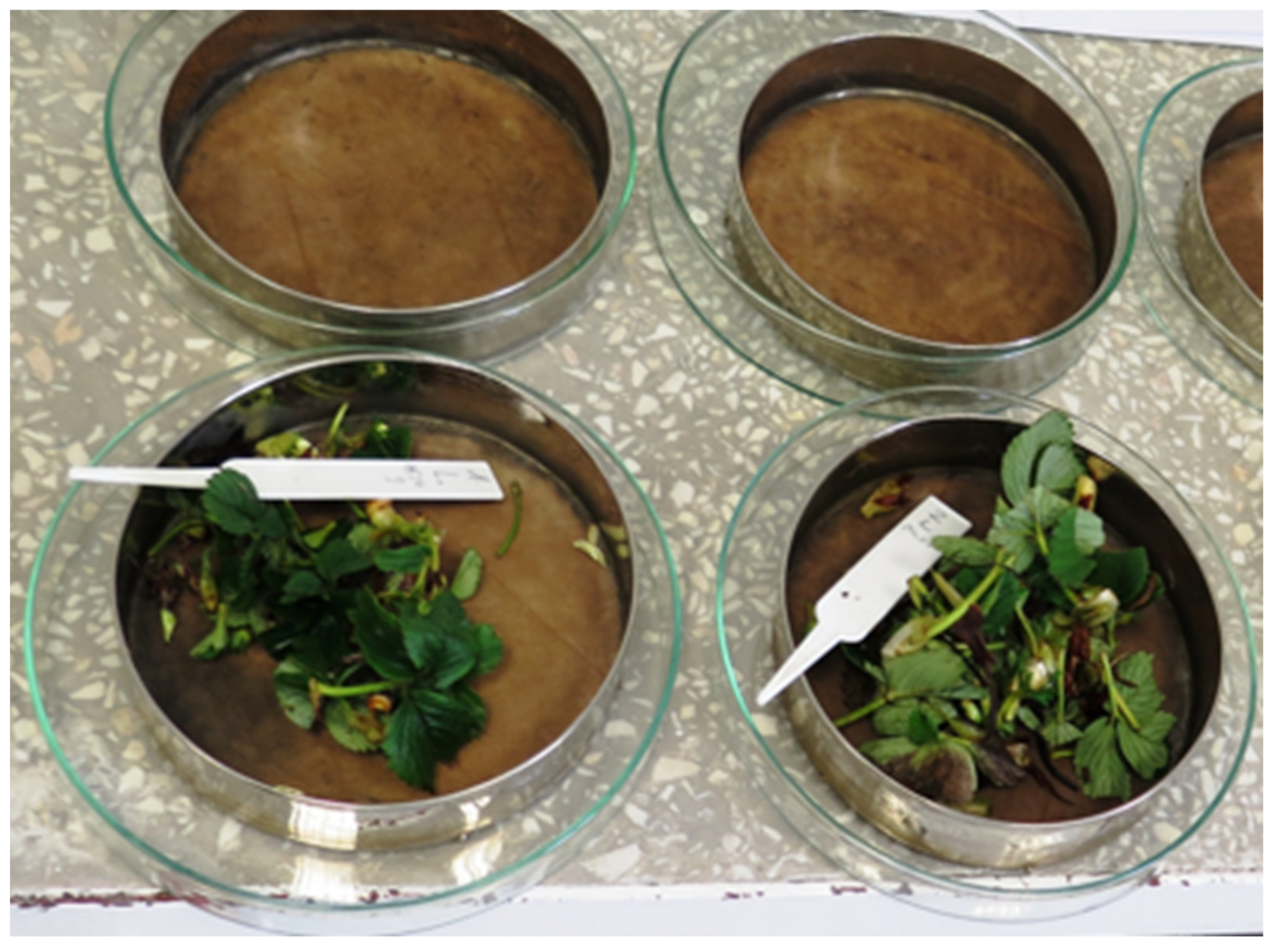

- Tintori, S.C.; Sloat, S.A.; Rockman, M.V. Rapid Isolation of Wild Nematodes by Baermann Funnel. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, 179, 10–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniland, L.N. A Modification of the Baermann Funnel Technique for the Collection of Nematodes from Plant Material. J. Helminthol. 1954, 28, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeski, M.W. Nematodes of Tylenchina in Poland and Temperate Europe; Muzeum i Instytutu Zoologii, Polska Akademia Nauk (MiIZ PAN): Warsaw, Poland, 1998; ISBN 83-85192-84-0. [Google Scholar]

- Andrássy, I. Free-Living Nematodes of Hungary (Nematoda Errantia). In Pedozoologica Hungarica; Csuzdi, C., Mahunka, S., Eds.; Hungarian Natural History Museum and Systematic Zoology Research Group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences: Budapest, Hungary, 2007; Volume II, ISBN 978-963508-574-3. [Google Scholar]

- Seinhorst, J.W. On the killing, fixation and transferring to glycerin of nematodes. Nematologica 1962, 8, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawberry Nutrient Management. Available online: https://extension.umn.edu/strawberry-farming/strawberry-nutrient-management (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Good Agricultural Practice: Strawberry Production. Available online: https://ati2.da.gov.ph/ati-car/content/sites/default/files/2022-12/gap_strawberry.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Lanauskas, J.; Uselis, N.; Valiuskaite, A.; Viskelis, P. Effect of foliar and soil applied fertilizers on strawberry healthiness, yield and berry quality. J. Agron. Res. 2006, 4, 47–250. Available online: https://agronomy.emu.ee/vol04Spec/p4S26.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bamouh, A.; Bouras, H.; Nakro, A. Effect of foliar potassium fertilization on yield and fruit quality of strawberry, raspberry and blueberry. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1265, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmanczyk, E.M.; Kozacki, D.; Hyk, W.; Muszyńska, M.; Sekrecka, M.; Skwiercz, A.T. In Vitro Study on Nematicidal Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Against Meloidogyne incognita. Molecules 2025, 30, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinovieva, S.V.; Udalova, Z.V.; Khasanova, O.S. Nanomaterials in Plant Protection against Parasitic Nemates. Usp. Sovrem. Biol. 2023, 143, 278–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandarosa. Available online: https://5porcji.pl/grandarosa-truskawka-doskonala-na-stol-i-do-ogrodu-dr-inz-agnieszka-masny-z-instytutu-ogrodnictwa/ (accessed on 22 July 2025). (In Polish).

- Masny, A.; Żurawicz, E.; Markowski, J. ‘Grandarosa’ Strawberry. HortScience 2015, 50, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszko, D. Wybrane problemy rachunku ekonomicznego na przykładzie specjalistycznych gospodarstw sadowniczych województwa lubelskiego. Zesz. Nauk. Inst. Sadow. Kwiac. Skiern. 2006, 14, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gołębiewska, B.; Sobczak, N. Kierunki wykorzystania i opłacalność produkcji truskawek. Zesz. Nauk. Szk. Gł. Gospod. Wiej. Warsz. Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywn. 2012, 98, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Seliga, J.; Studnicki, M.; Wójcik-Gront, E. Evaluating economic value of 23 strawberry cultivars in the climatic conditions of central Europe. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2017, 16, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wróblewska, W.; Pawlak, J.; Paszko, D. The influence of factors on the yields of two raspberry varieties (Rubus idaeus L.) and the economic results. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2020, 19, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittori, L.D.; Mazzoni, L.; Battino, M.; Mezzetti, B. Pre-harvest factors influencing the quality of berries. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, P.; Zmarlicki, K. Zmiany kosztów jednostkowych produkcji ekologicznej truskawek w latach 2009–2013. Rocz. Nauk. SERiA 2015, 117, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zmarlicki, K.; Brzozowski, P. Perspektywy, Szanse i Zagrożenia dla Produkcji Truskawek, Jagody Kamczackiej i Aronii; Instytut Ogrodnictwa: Skierniewice, Poland, 2020; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, J.; Wróblewska, W.; Paszko, D. Production and economic efficiency in the cultivation of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) depending on the method of production—Case study. Agron. Sci. 2022, 77, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location: Skierniewice, Poland (51°96′15″ N, 20°13′69″ E) Host Plant: Fragaria × ananassa | ||

|---|---|---|

| Character | (X1–X10) | Mean ± SD |

| Body length L | 568.5–876.8 | 764.0 ± 94.7 |

| Stylet length | 9.7–11.0 | 10.2 ± 0.4 |

| Tail length | 36.3–55.4 | 46.4 ± 6.6 |

| PUS% | 31.7–69.8 | 54.8 ± 0.1 |

| a | 45.8–61.5 | 55.8 ± 3.1 |

| b’ | 4.6–6.6 | 6.5 ± 0.6 |

| c | 11.9–18.3 | 16.3 ± 1.8 |

| c’ | 4.1–6.2 | 5.1 ± 0.4 |

| V/AT | 3.0–5.4 | 4.4 ± 0.7 |

| V% | 58.0–76.4 | 70.0 ± 3.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skwiercz, A.; Sekrecka, M.; Trzewik, A.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Stefanovska, T.; Husieva, A.; Zapałowska, A.; Masłoń, A. Effect of Soil Treatments with Vermicompost and Ag+ on Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Inoculated with the Leaf Nematode Aphelenchoides Fragariae. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122900

Skwiercz A, Sekrecka M, Trzewik A, Wawrzyniak A, Stefanovska T, Husieva A, Zapałowska A, Masłoń A. Effect of Soil Treatments with Vermicompost and Ag+ on Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Inoculated with the Leaf Nematode Aphelenchoides Fragariae. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122900

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkwiercz, Andrzej, Małgorzata Sekrecka, Aleksandra Trzewik, Anna Wawrzyniak, Tatyana Stefanovska, Anastasiia Husieva, Anita Zapałowska, and Adam Masłoń. 2025. "Effect of Soil Treatments with Vermicompost and Ag+ on Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Inoculated with the Leaf Nematode Aphelenchoides Fragariae" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122900

APA StyleSkwiercz, A., Sekrecka, M., Trzewik, A., Wawrzyniak, A., Stefanovska, T., Husieva, A., Zapałowska, A., & Masłoń, A. (2025). Effect of Soil Treatments with Vermicompost and Ag+ on Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Inoculated with the Leaf Nematode Aphelenchoides Fragariae. Agronomy, 15(12), 2900. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122900