1. Introduction

Plum (

Prunus salicina Lindl.), a perennial drupe tree species within the Rosaceae family, represents one of the fruit crops with considerable economic importance worldwide, with China accounting for the largest cultivation area [

1,

2]. Plum fruits are rich in phenolic compounds such as anthocyanins and flavonoids, pectin, vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients, which play an important role in the daily diet of consumers [

3,

4,

5]. The sugar–acid balance is a decisive determinant of fruit flavor quality, with profound implications for consumer preference, marketability, postharvest longevity, and processing suitability [

6]. The ‘Fengtang’ plum, renowned as the “Hermes of plums”, is a premium local variety grown in Liuma Town, Zhenning County, Anshun City, Guizhou Province, and has been recognized as a National Geographical Indication product [

7]. As a distinctive germplasm resource in China, ‘Fengtang’ plum is highly appreciated for its exceptional fruit quality, characterized by large fruit size, crisp and firm texture, and notably high total soluble solids (TSS) compared to other varieties. These attributes underpin its strong competitiveness in the fresh fruit market [

8]. For instance, the maximum total soluble solids reported for mature green crisp plums in the Chongqing area is approximately 11.0%, while that of Sanhua plums, primarily cultivated in Guangdong Province, reaches only about 9.5% [

9,

10]. In contrast, the ‘Fengtang’ plum exhibits a remarkably high TSS content of up to 20.0%, indicating a superior sugar accumulation capacity. This pronounced disparity suggests the presence of a unique sugar metabolism regulatory mechanism in ‘Fengtang’ plum that warrants further in-depth investigation.

Sugar metabolism, a central physiological process governing fruit quality, along with its molecular mechanisms and regulatory pathways, has garnered significant research interest. Photosynthetic products such as sucrose and sorbitol are transported from leaves into the fruit vacuole for storage via plasmodesmata and specific sugar transporters, directly influencing sugar distribution and accumulation patterns [

11]. As highlighted by Hu et al., soluble sugars not only serve as key substrates in energy metabolism but also act as signaling molecules that modulate fruit development and stress responses [

12]. Fruit sweetness is predominantly determined by the composition and proportion of fructose, glucose, and sucrose. During the ripening of fruits such as kiwifruit, substantial sucrose accumulation often occurs, a dynamic process critically shaping flavor and postharvest quality [

13,

14]. Studies have shown that sucrose synthase (SS) and sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS) act synergistically to regulate sucrose synthesis and degradation, while acidic invertase (AI) and neutral invertase (NI) catalyze the hydrolysis of sucrose into monosaccharides. Furthermore, fructokinase (FK) and hexokinase (HK) phosphorylate these sugars to channel metabolites into key pathways including the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and starch biosynthesis [

15]. Postharvest storage studies indicate that continued accumulation of soluble sugars enhances the content of flavor compounds and improves overall fruit quality [

16]. Research on carbohydrate metabolism across developmental stages has revealed that in early phases, Prunus fruits mainly accumulate fructose and glucose, whereas sucrose synthesis capacity strengthens markedly toward maturity [

17]. Similar dynamic patterns of sugar metabolism have been observed in other economically important fruit crops, including apples, apricots, and bayberries, providing a solid theoretical basis for targeted regulation of fruit quality [

18,

19,

20].

In the sensory quality system of fleshy fruits, organic acids and carbohydrates form a dual-core regulatory module that fundamentally shapes flavor perception. A comparative study of organic acid profiles in mature fruits across species revealed significant differences in the accumulation of specific acids. Malic acid was identified as the predominant organic acid in fruits of the genus Malus, the genus Pyrus, and the subgenus Prunus [

21,

22,

23]. In contrast, citric acid was specifically enriched in fruits of Citrus (Rutaceae), Vitis (Vitaceae), and strawberry (Rosaceae) [

24,

25]. The fruit acidity phenotype is largely shaped by the spatiotemporal expression patterns of the malic-citric acid metabolic network within the peel parenchyma cells. This network is driven by four core metabolic pathways operating in concert: the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in the mitochondrial matrix supplies carbon skeletons; glycolytic-acid cycling (GAC) mediates carbon flux redistribution; the malate-based citrate cleavage and oxidative decarboxylation pathway regulates carbon-chain shortening and generation of reducing equivalents; and the cytoplasmic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) cascade facilitates oxaloacetate synthesis [

26]. These pathways achieve synergistic regulation through intercompartmental metabolite transport, along with post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications, ultimately determining the quantitative accumulation and compositional profile of the fruit organic acid pool.

During the development and maturation of ‘Fengtang’ plum fruit, its metabolic profile undergoes significant changes. In this study, a metabolomics approach based on liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was employed to systematically investigate the dynamics of carbohydrate and organic acid metabolism across three key developmental stages of the fruit. Multivariate statistical analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), were applied to uncover the dynamic regulatory network and identify key biomarkers within the sugar–acid metabolic pathways. The research objective is to elucidate the sugar–acid composition of the ‘Fengtang’ plum and its metabolic mechanisms, thereby providing a theoretical foundation and technical support for its pre-harvest cultivation management and post-harvest quality control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Treatment

The ‘Fengtang’ plum sample was collected on 25 May 2024 from the standardized planting base in Liuma Town, Zhenning County, Anshun City, Guizhou Province (geographical coordinates: 105°35′ to 106°01′ east longitude, 25°25′ to 26°11′ north latitude). The initial sampling was conducted 90 days after flowering, corresponding to the pre-color-change stage of fruit development. Subsequent sampling time points were determined on the basis of fruit developmental patterns and in consultation with local cultivation experts, with collections scheduled at 10-day intervals. Three plum trees cultivated under uniform environmental conditions were selected as biological replicates to ensure consistent and representative sampling. To minimize the effect of light exposure and canopy position on metabolite profiles, fruits were specifically harvested from the middle-upper, outer canopy on the sun-exposed side of each tree, ensuring comparable light conditions. At each developmental stage (PR, VR, FR), a total of 90 fruits were harvested, with 30 fruits being collected from each tree. The entire edible portion of the fruits (including the peel) was cut into pieces, thoroughly mixed, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent metabolomic analysis.

2.2. Firmness, TSS, TA, Sugar–Acid Ratio and Color Difference Measurements

The determination was performed in accordance with the method described by Zhang et al. [

27]. The firmness of the fruit was measured using a texture analyser (TA.XT.Plus SMS, Godalming, UK) on symmetrical regions along the equator of the ‘Fengtang’ plum. The measurements were conducted using a cylindrical P/2 probe with a diameter of 2 mm. The initial velocity was set to 2 mm·s

−1, and the test velocity was 1 mm·s

−1, with the force being 5 g. Following the process of compression, the probe returned to its original position at a velocity of 2 mm·s

−1. The values of firmness were expressed in Newtons (N).

The measurement of total soluble solids (TSS) was conducted utilising a PAL-1 digital refractometer (ATAGO, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to measurement, the instrument was calibrated with distilled water. A droplet of juice from the ‘Fengtang’ plum sample was placed on the prism surface, and the refractive index was recorded directly. Each sample was measured in triplicate, and the results are expressed as a percentage of the mass.

The titratable acidity (TA) was determined according to the acid-base neutralisation method as described by Tang et al. with minor modifications [

28]. In summary, 1.0 g of fruit pulp was meticulously weighed and homogenised. The resulting homogenate was then titrated with a 0.1 M NaOH standard solution, with 1% phenolphthalein employed as an indicator. The titration endpoint was defined as the appearance of a faint pink colour that persisted for 30 s. The TA was calculated based on malic acid equivalence and expressed as a percentage.

Six ‘Fengtang’ plum fruits at varying stages of development were selected for the purpose of conducting a colour analysis. Color parameters were measured using a calibrated UltraScan Pro fully automated spectrophotometric colorimeter (HunterLab, Fairfax, VA, USA), with a standard whiteboard used for calibration. Two undamaged sites in the equatorial region of each fruit were selected for measurement. The L*,

a*, and

b* values were recorded, and the average of three parallel measurements was calculated for each parameter. The total colour difference (ΔE) was calculated using the following formula:

2.3. Metabolomics Determination of UPLC-MS/MS

The extraction and assay of the metabolites of ‘Fengtang’ plums were undertaken by Wuhan MetWare Biotechnology Co. (Wuhan, China). The experimental method was optimized in accordance with the study protocol of Chen et al.: the samples were first subjected to pretreatment by a Scientz-100F (Ningbo Scientz, Ningbo, China) vacuum freeze dryer, followed by crushing at 30 Hz for 1.5 min using an MM 400 grinder from Retsch (German Lechi), Wetzlar, Germany, to obtain a homogeneous powder [

29].

Following the accurate weighing of 50 mg of the sample powder, extraction was conducted by adding an aqueous solution containing 70% methanol, which was pre-cooled to −20 °C, in the ratio of 1:24 (mass to volume ratio). The mixture was subjected to a centrifugal process at a speed of 12,000 revolutions per minute for a duration of 3 min. The resultant upper layer was collected and subsequently filtered using a microporous membrane with a 0.22-micron pore size to ensure sterilization. The treated samples were then stored in injection bottles and analyzed subsequently by LC-MS/MS.

The analytical method was based on an Exion LC AD ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA, USA) coupled with a 6500 QTRAP triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, USA) platform. The chromatographic separation was conducted on an Agilent SB-C18 reversed-phase column (2.1 mm × 100 mm), with mobile phase A consisting of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution and mobile phase B comprising 0.1% formic acid acetonitrile solution. The gradient elution procedure was as follows—The proportion of mobile phase A was systematically reduced from 95% to 5% over the range of 0–9. The gradient elution procedure was initiated as follows: firstly, the proportion of mobile phase A was linearly reduced from 95% to 5% between 0 and 9.0 min; secondly, 5% of mobile phase A was maintained for 9.0–10.0 min; thirdly, the gradient was restored to 95% of mobile phase A between 10.0–11.1 min; and finally, the equilibrium was maintained until 14.0 min. The chromatographic parameters that were utilized are outlined below: a flow rate of 0.35 mL min−1, a column temperature of 40 °C, and an injection volume of 2 μL.

The mass spectrometry detection utilized both positive and negative ion modes for data acquisition in the ionization session, wherein the heating temperature of the ion source was maintained at a level of 500 °C and spray voltages of 5500 V and −4500 V were applied in accordance with the difference in detection modes. In the configuration of the gas system, the ion source auxiliary gas I (GSI) and auxiliary gas II (GSII) were set to 50 psi and 60 psi, respectively, while the pressure of the gas curtain gas (CUR) was adjusted to 25 psi. Nitrogen gas at a medium pressure was continuously passed through the collision chamber as the collision gas. The detection method was based on the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) technique, and the optimal combination of depolymerization potential (DP) and collision energy (CE) parameters for each metabolite was determined by system optimization. To enhance the detection sensitivity, the experimenters divided the total acquisition time into multiple time windows for segmented MRM based on the peak time distribution characteristics of the target metabolites on the chromatographic column.

The specific process of our mass spectrometry-based metabolite identification is as follows: during the qualitative analysis stage, mass spectrometry data from experimental samples were matched against reference parameters in the MetWare database (MWDB). Matching criteria included the precise precursor mass (Q1, with a mass tolerance of 20 ppm), secondary fragmentation spectra (MS

2, also with 20 ppm tolerance), chromatographic retention time (RT, within 0.2 min tolerance), and isotopic distribution patterns. Metabolites identified using authentic standards available in the database were explicitly labeled as such. For those without commercially available standards, identification was supported by matching experimental MS

2 spectra and RT against database records derived from literature and public repositories. In the quantitative phase, multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB Sciex 4500 QTRAP, Foster City, CA, USA) was employed to ensure high specificity and sensitivity. Data processing, including peak detection, alignment, and normalization, was performed using MultiQuantTM 3.0.3 Software. Normalized peak areas were used to represent relative metabolite abundances. This integrated approach—combining high-resolution qualitative data with robust MRM-based quantification—has been successfully applied and validated in previous plant metabolomics studies, including work by Chen et al. [

29].

2.4. Confidence Levels for Metabolite Identification

To ensure the reliability of metabolite identification, a three-tiered confidence level system was applied, consistent with metabolomics reporting standards:

Level 1: Confidently identified using authentic standards, with matching precursor mass (Q1), fragment mass (Q3), retention time (RT), and a high spectral similarity score (MS/MS score > 0.7).

Level 2: Putatively annotated based on high spectral similarity (MS/MS score between 0.5 and 0.7) without a standard.

Level 3: Putatively characterized based on Q1, Q3, and RT match only, without reliable MS/MS spectral support.

Stringent tolerances were applied throughout the identification process: mass tolerance of 2 ppm for Q1 and 5 ppm for Q3, and RT tolerance of 0.2 min. All chromatographic peaks were manually reviewed and corrected where necessary to ensure accurate integration and identification.

Note on Sugar Derivatives Identification: Sugar derivatives are notoriously difficult to distinguish under reversed-phase C18 chromatography with a gradient starting from 5% acetonitrile. To enhance identification confidence for this critical class, we relied on high-resolution MS/MS spectra and cross-referenced with public metabolite databases. Where standards were unavailable, putative annotations are clearly indicated (Level 2 or 3).

2.5. Data Analysis

The analysis of the study’s data was conducted using professional statistical software, with the visualization of experimental data being achieved through GraphPad Prism 10 and the application of statistical inference being conducted with SPSS 23. To assess the significance of differences between multiple groups, post hoc analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA combined with multiple comparison tests. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and differences were considered statistically significant at

p < 0.05. The visual analysis of metabolomics data was conducted utilizing the Metware Bioinformatics Cloud Platform (

https://cloud.metware.cn/, accessed on 3 April 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Changes in the Quality of ‘Fengtang’ Plums at Different Developmental Stages

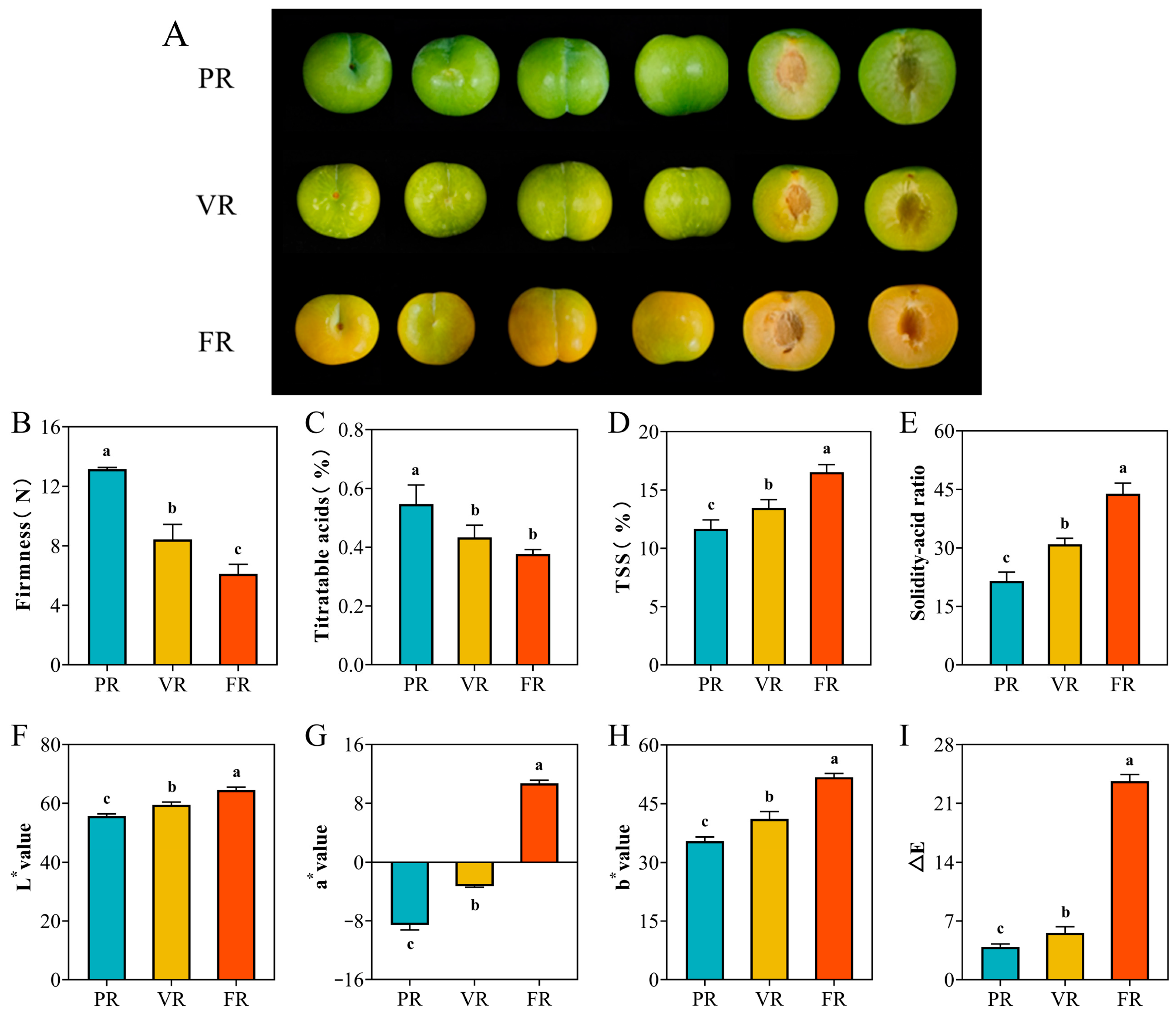

As demonstrated in

Figure 1A, the ‘Fengtang’ plum exhibits substantial disparities in the three stages of color change: the fruit is dark green in the PR stage, exhibits a light yellow color in the VR stage, and manifests a golden yellow color in the FR stage. As the fruit ripens, its firmness gradually decreases. Upon attaining optimal ripeness and subsequent placement on the market, the fruit’s firmness is recorded as approximately 6 Newtons (

Figure 1B). Soluble solids (TSS), which are primarily composed of glucose, fructose, and sucrose, undergo a gradual increase in proportion with the progression of fruit maturity. These soluble solids can reach concentrations of between 15% and 17% once the color change has been fully completed (

Figure 1C). Concurrently, the total acid content (TA) of the fruit underwent a substantial decline, from an initial level of 0.61% to a range of 0.36% to 0.39% at the stage of full maturity (

Figure 1D). As the development process progresses, the sugar–acid ratio (TSS/TA) of the ‘Fengtang’ plum fruit displays an exponential growth trend, increasing from 21.5 to 43.8 (

Figure 1E). This finding indicates that the mature fruit of the ‘Fengtang’ plum possesses a distinctive characteristic of high sugar and low acid, which is significantly different from other plum fruits.

Through chromaticity measurement and analysis, it was found that the epidermal color of the ‘Fengtang’ plum fruit showed regular changes during the fruit development process (

Figure 1F–I). At the initial stage of fruit color change, the fruit surface presented typical dark green characteristics, and its L* value remained within the range of 55.6 ± 1.0. As the fruit entered the final stage of the color change period, a significant upward trend was observed in the L* value (

p < 0.05), eventually reaching 64.2 ± 1.5 (

Figure 1F). In terms of the hue dimension, the

a* value underwent a gradual transition from an initial value of −8.4 ± 0.8 (indicative of a dark green characteristic) to a positive value, reaching 10.6 ± 0.6 at the conclusion of the color change (

Figure 1G). The changing trend of the

b* value is also the same, continuously rising from the initial 35.7 ± 1.5 to 51.8 ± 1.0 (

Figure 1H). The most significant of these changes was found to be the dynamic change in ΔE, which reached 3.8 ± 0.5 at the initial stage of color change and 23.7 ± 1.2 at the end of color change (

Figure 1I). These physiological changes suggest a profound reprogramming of sugar and acid metabolism during fruit development, which was further investigated through metabolomic profiling.

3.2. Metabolomics Analysis of ‘Fengtang’ Plums at Different Developmental Stages

To elucidate the metabolic basis underlying the observed changes in sugar and acidity, widely targeted metabolomics was performed on fruit samples from the three developmental stages. The total ion chromatography (TIC) of the quality control (QC) samples in the extraction and detection system of secondary metabolites of ‘Fengtang’ plum was systematically evaluated by using the superimposed analysis technique. The experimental data demonstrate that under both positive and negative ionisation modes, the total ion chromatography curves of QC samples exhibit a high degree of overlap. The specific quality parameters demonstrate that the relative deviation fluctuation range of the chromatographic peak retention time is controlled within 0.5%, while the difference in peak area is stably maintained below 8.3%. The assessment results effectively verified the stability and repeatability of the experimental system, thereby laying a methodological foundation for the precise analysis of metabolite differences at different developmental stages in non-targeted metabolomics research. Furthermore, the assessment results strongly ensured the scientific nature and comparability of the experimental data.

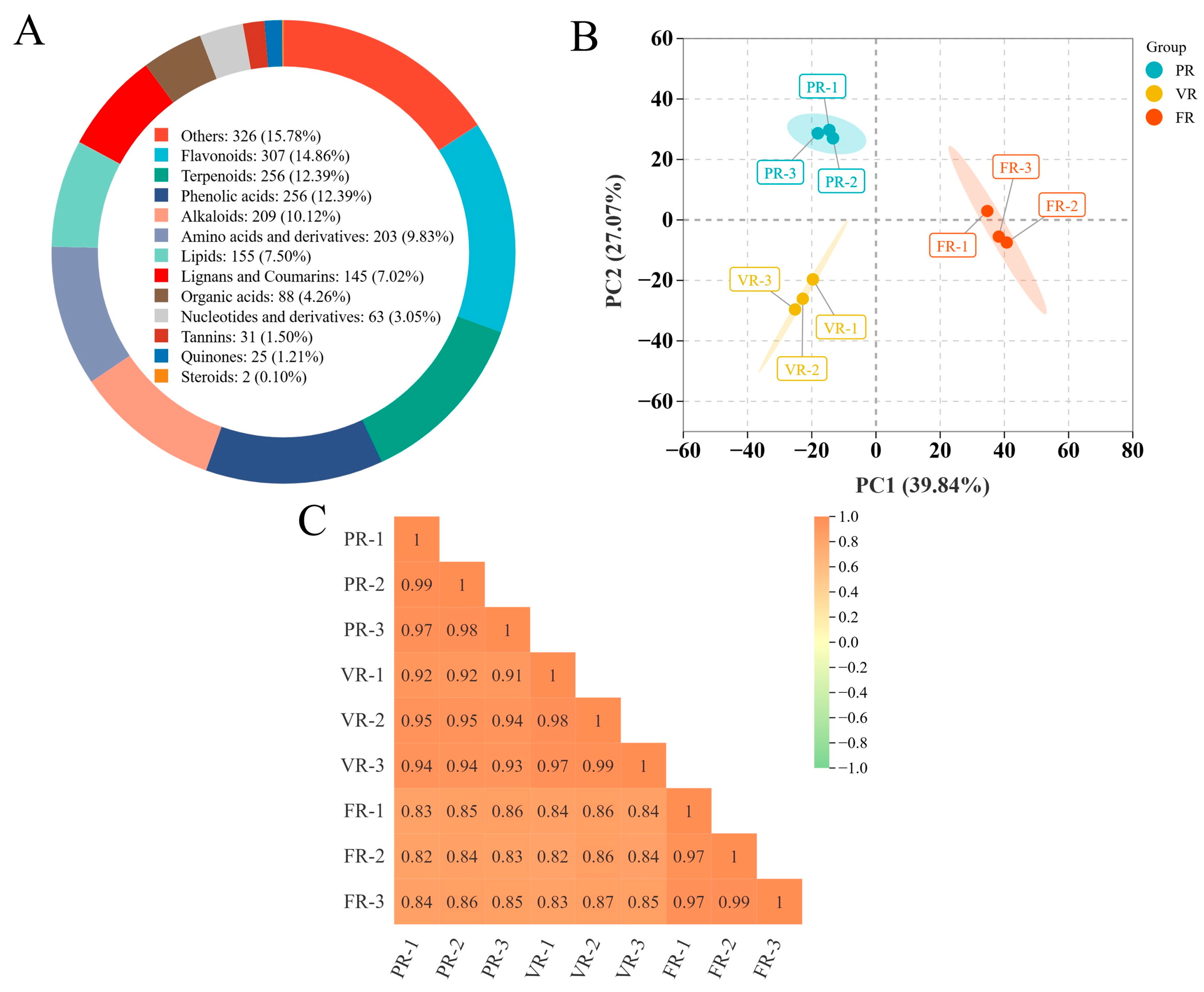

A total of 2003 metabolites were identified in the ‘Fengtang’ plum samples and classified into 12 categories based on their chemical properties. The specific distribution is as follows: amino acids and derivatives constituted 9.83% of the detected metabolites. Phenolic acids constituted 12.39% of the detected metabolites. Terpenoids constituted 12.39% of the detected metabolites. Alkaloids constituted 12% of the detected metabolites. Flavonoids constituted 14.86% of the detected metabolites. Other components constituted 15.78% of the detected metabolites. Tannins constituted 1.5% of the detected metabolites. Organic acids constituted 4.26% of the detected metabolites. Quinones constituted 1.21% of the detected metabolites. Lignans and coumarins constituted 7.2% of the detected metabolites. Lipids constituted 7.5% of the detected metabolites. Steroids constituted 0.1% of the detected metabolites (

Figure 2A).

In this paper, the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) method was adopted for the purpose of conducting dimensionality reduction processing on multi-dimensional metabolome data. The results demonstrate that the initial two principal components, designated PC1 and PC2, respectively, account for 39.84% and 27.07% of the total variance, thereby achieving a cumulative contribution rate of 66.91%. The two-dimensional scatter plot (

Figure 2B) visually presents the distribution characteristics of the samples in the dimensionality reduction space. The quality control samples are highly concentrated, reflecting the good stability of the experimental system and the controllability of data quality. Samples at differing developmental stages (PR, VR, FR) demonstrate significant spatial separation, while samples within each stage exhibit a closely aggregated state. This distribution pattern not only reveals the metabolic characteristics specific to the developmental stage but also verifies the reliability of biological repetition. Furthermore, an analysis of the correlation coefficient matrix revealed that the mean correlation coefficient of the metabolic profiles of samples within each developmental stage group attained 0.80 (

Figure 2C). The high consistency of the results further confirmed the repeatability of the experimental data and laid a solid foundation for the subsequent functional analysis of metabolic pathways.

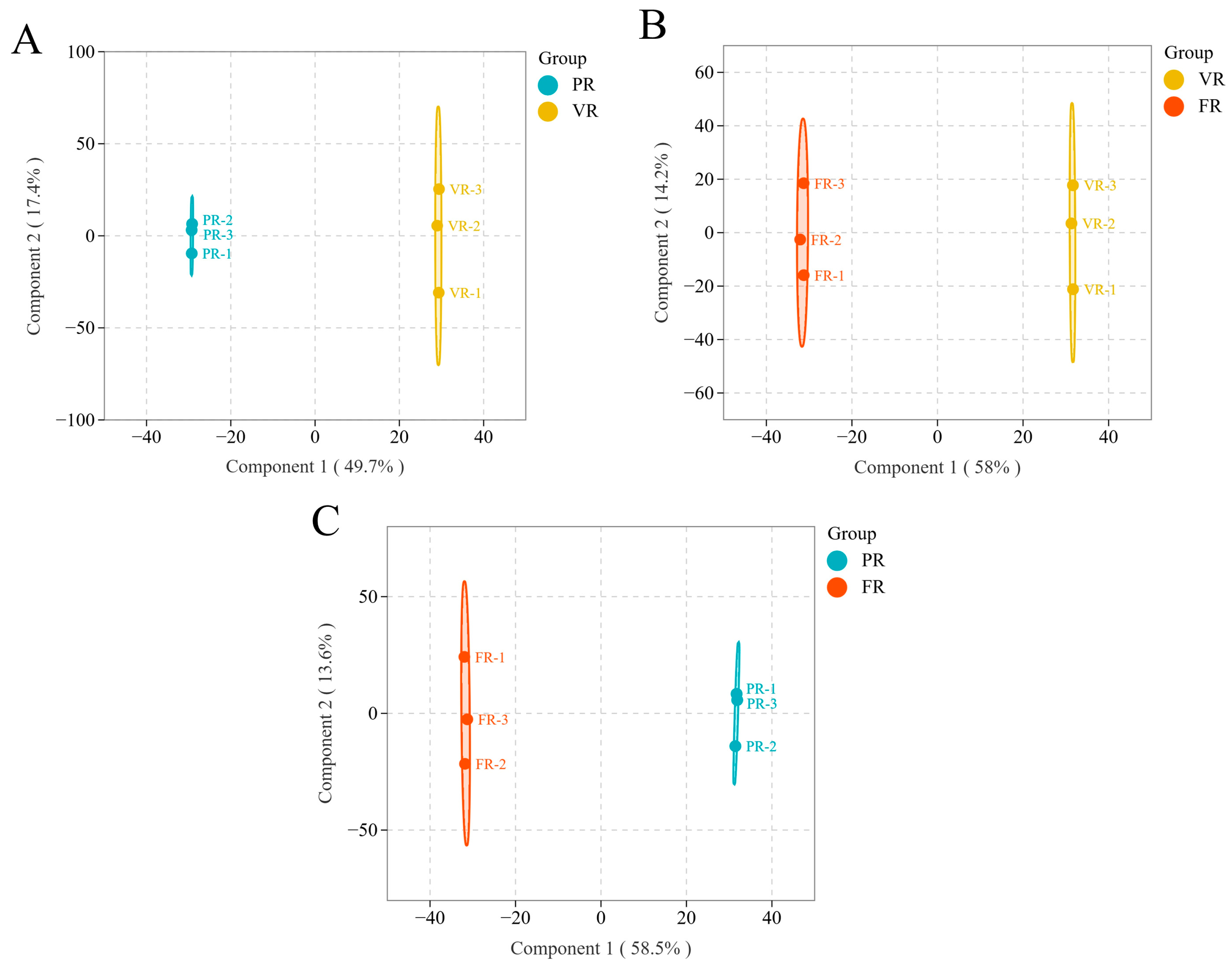

3.3. Analysis of ‘Fengtang’ Plum OPLS-DA at Different Developmental Stages

To identify stage-specific metabolic signatures associated with sugar–acid balance, orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was conducted between each pair of developmental stages. In the domain of metabolomics research, the predictive robustness and explanatory power of models are typically evaluated by three complementary indicators: Q

2, R

2X, and R

2Y. Among them, Q

2 (cross-validation prediction determination coefficient) is regarded as a key parameter for measuring the generalization ability of the model. When Q

2 is greater than 0.9 and R

2X and R

2Y are close to 1, it indicates that the model not only has an excellent fitting effect but also has good prediction stability and can effectively avoid the risk of overfitting. The objective of this analysis was to comprehensively explore the dynamic change characteristics of its glycolic acid metabolism. The effectiveness of the model in identifying key differential metabolites is further evaluated by constructing the latent variable relationship between the high-dimensional metabolite spectrum and the grouping variables. The experimental findings demonstrate that the samples at varying developmental stages in

Figure 3A–C manifest clear clustering tendencies and substantial separation trajectories, providing a compelling substantiation of the high-resolution capacity of OPLS-DA in distinguishing metabolic phenotypes specific to distinct periods.

In the context of the OPLS-DA model, the R

2X index is indicative of the variation ratio of the cumulative interpretation of the model for the independent variable matrix (i.e, the metabolite abundance matrix). Concurrently, the R

2Y index quantifies the degree to which the model aligns with the dependent variable matrix (i.e, the grouping variable). Q

2 employs a seven-fold cross-validation method to assess the model’s predictive ability for external samples. All the statistical parameters of the paired comparison models in this study performed exceptionally well: the R

2X values ranged from 0.671 to 0.722, indicating that the models effectively captured over 67% of the metabolite variations. The model successfully interpreted the grouping information, as evidenced by the convergence of R

2 and Y on a value of 1. The Q

2 value ranges from 0.948 to 0.964, which is significantly higher than the judgement threshold of 0.9. This demonstrates the model’s robust predictive performance on unknown samples (

Table 1). The results presented above provide substantial evidence that the established OPLS-DA model exhibits both adequate goodness of fit and remarkable predictive reliability. The method has been shown to accurately identify and distinguish the characteristic glycolic acid metabolites of ‘Fengtang’ plum at different developmental stages. This provides solid theoretical and methodological support for the elucidation of the temporal mechanism of fruit quality formation.

3.4. Identification of Sugar Acid Metabolites in the Fruits of ‘Fengtang’ Plum at Different Developmental Stages

Differential metabolite screening focused on sugars, organic acids, and their immediate derivatives to pinpoint compounds directly linked to the shifting sugar–acid profile. In the differential screening study of sugar acid metabolites, this study employed OPLS-DA to systematically compare the three key developmental stages of PR, VR, and FR. In order to accurately identify differentially expressed metabolites with biological significance, a triple screening criterion has been established. This criterion comprises the following three elements: the absolute value of the folding multiple (FC) of the metabolite abundance change is required to be ≥1; The projected value of variable importance (VIP) in the prediction of the OPLS-DA model is required to be ≥1; The

p-value of the univariate statistical test corrected by Benjamini–Hochberg is required to be <0.05. Metabolites that simultaneously meet the aforementioned three criteria are defined as significantly different metabolites, and the screening results are visually presented through a volcano plot to intuitively demonstrate the distribution characteristics of the metabolites between statistical significance and the range of expression changes (

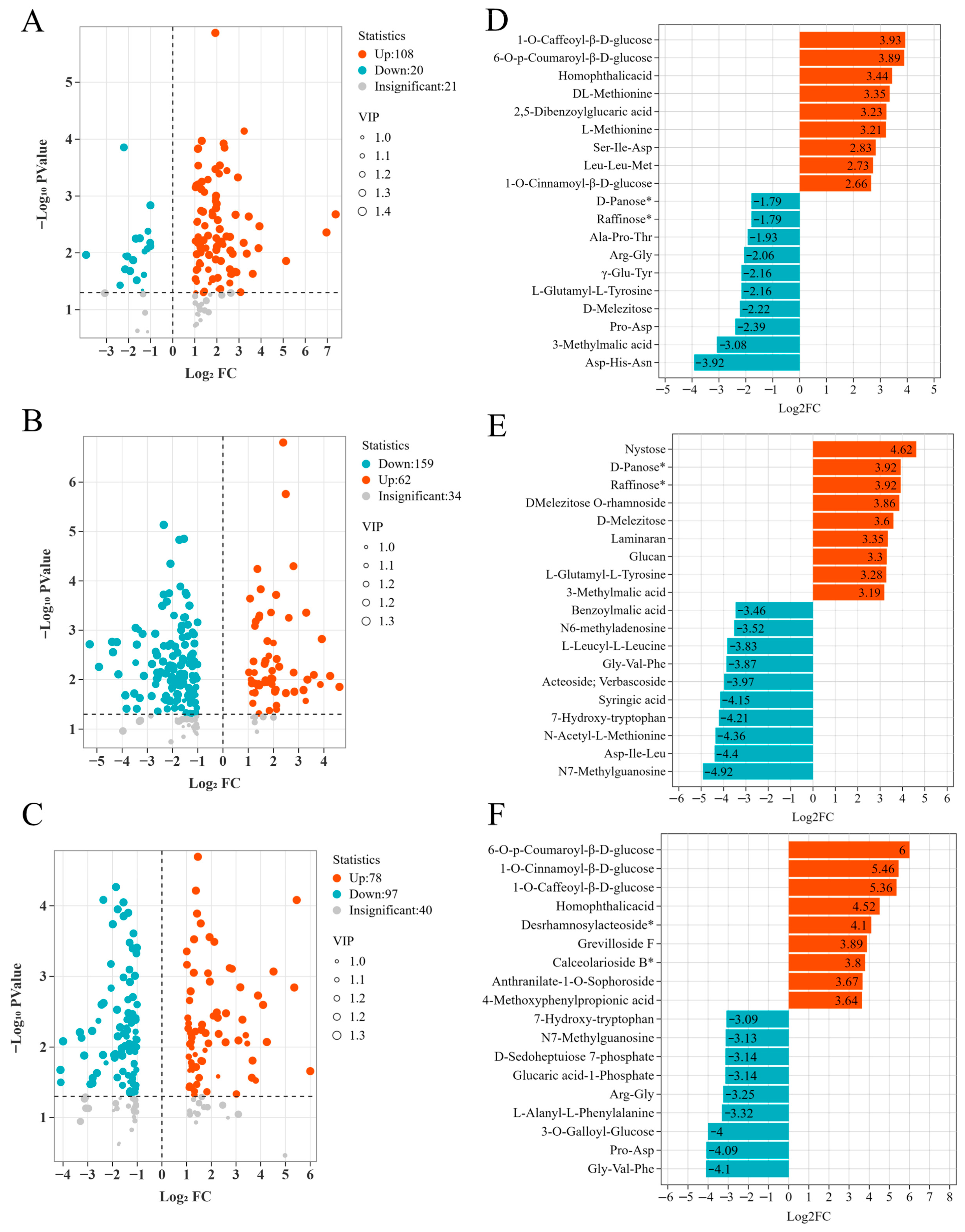

Figure 4A–C). During the developmental transition from the PR stage to the VR stage, a total of 149 significantly different sugar acid metabolites were identified. Among them, 108 metabolites exhibited an upward trend, accounting for 72.5%, indicating that metabolic activities were generally enhanced at this stage. However, 20 metabolites exhibited a downward trend, accounting for 13.4%, indicative of the inhibition of certain metabolic pathways. It is noteworthy that upon the transition from the VR phase to the FR phase, the number of differential metabolites increases to 255, and the expression pattern undergoes a significant reversal: a mere 62 metabolites remain up-regulated, accounting for 24.3%, while 159 metabolites are down-regulated, accounting for 62.4%. This phenomenon suggests that the mature initiation phase is accompanied by large-scale metabolic reprogramming. In the cross-stage comparison (FR vs. PR), a total of 215 significantly differentially expressed metabolites were detected, among which 78 were found to be overexpressed, accounting for 36.3%. A total of 97 downgrades were recorded, representing 45.1% of the total. While the remaining metabolites did meet the criteria for significant difference, they did not demonstrate a single expression trend. The results presented herein not only reveal the characteristic changes in sugar acid metabolites at different stages of the color change process but also provide an important theoretical basis for further exploration of the regulatory mechanism and potential biological functions of metabolites during this process.

3.5. Changes in Sugar–Acid Metabolites in Fruits of ‘Fengtang’ Plum at Different Developmental Stages

In order to further investigate changes in sugar and acid metabolites in ‘Fengtang’ plum fruits at different developmental stages, differential metabolites identified via volcano plot analysis underwent differential analysis. The generation of differential bar charts was undertaken for the purpose of conducting a visual analysis of changes in sugar and acid metabolites across developmental stages (

Figure 4D–F).

In the comparative analysis of PR and VR (

Figure 4D), the top 9 metabolites that were significantly upregulated mainly belonged to two major categories: phenolic acid compounds and amino acids and their derivatives. Among them, Phenolic acid substances include 1-O-Caffeoyl-β-D-glucose (15.22-fold), 6-O-p-Coumaroyl-β-D-glucose (14.79-fold), Homophthalicacid (10.87-fold), and 2, 5-dibenzoylglucar The significant accumulation of substances such as ic acid (9.41-fold) and 1-O-Cinnamoyl-β-D-glucose (6.34-fold) may be closely related to the construction of the antioxidant system and the activation of the secondary metabolic network in the early stage of fruit development; Amino acids and their derivatives include DL-Methionine (10.21-fold), L-Methionine (9.25-fold), Ser-Ile-Asp (7.10-fold), and Leu-Leu-Met (6.63-fold). Its high upregulation indicates that the synthesis of peptide substances related to protein anabolism and signal transduction is relatively active at this stage. Among the top 10 metabolites that were significantly downregulated, the relative contents of three carbohydrate metabolites (Raffinose* and D-Panose*) were all 0.29-fold; although the proportions of D-Melezitose (0.22-fold) and one organic acid (3-Methylmalic acid, 0.12-fold) are low, there may be the consumption of carbohydrate substances and the weakening of organic acid metabolism in the PR to VR stage. The rest are all down-regulation of amino acids and their derivatives. It reflects that the activity of some amino acid metabolic branches was inhibited during this period.

The comparison results of VR and FR (

Figure 4E) show that the top 9 upregulated metabolites cover three major categories: sugars, organic acids, and amino acids and their derivatives. The relative content changes range from 0.03 to 25.54-fold. Among the organic acids, 3-Methylmalic acid is upregulated by 9.14-fold. The upregulation range of carbohydrate metabolites (Nystose, Raffinose*, D-Panose*, DMelezitose O-rhamnoside, D-Melezitose, Laminaran and Glucan) reached 9.84–25.54-fold. This feature is highly consistent with the physiological requirements during the fruit ripening process for sugar accumulation to enhance sweetness and dynamic adjustment of organic acids to optimize flavor. Among the top 9 downregulated metabolites, the significant reduction in two phenolic acid substances (Benzoylmalic acid, 0.09-fold and Syringic acid, 0.06-fold) may be related to the shift in the secondary metabolic focus to carbohydrate synthesis related to energy storage during the fruit ripening stage.

In the cross-stage comparison of FR and PR (

Figure 4F), among the top 8 upregulated metabolites, 6-O-p-Coumaroyl-β-D-glucose, 1-O-Cinnamoyl-β-D-glucose, 1-O-Caffeoyl-β-D-glucose, Homophthalicacid, G revilloside F, Calceolarioside B*, Anthranilate-1-O-Sophoroside and 4-Methoxyphenylpropionic acid are all phenolic acid compounds. The increase range of its relative content is 12.47–64.2-fold, suggesting that phenolic acid substances undergo a dynamic process of phased accumulation throughout the entire development cycle from young fruits to maturity, and may play a core role in the construction of antioxidant capacity and the formation of quality characteristics of fruits. Among the top 9 downregulated metabolites, the relative content of only one carbohydrate substance (Glucaric acid-1-Phosphate) was 0.11-fold. Its significant reduction might be related to the adjustment of metabolic flow in the glucose metabolism pathway from phosphorylated intermediate products to free soluble sugars during the fruit ripening stage.

The up-regulation of phenolic acids in early stages may contribute to antioxidant defense, while the later surge in oligosaccharides such as raffinose aligns with the marked increase in TSS, suggesting a role in osmotic regulation and sugar storage.

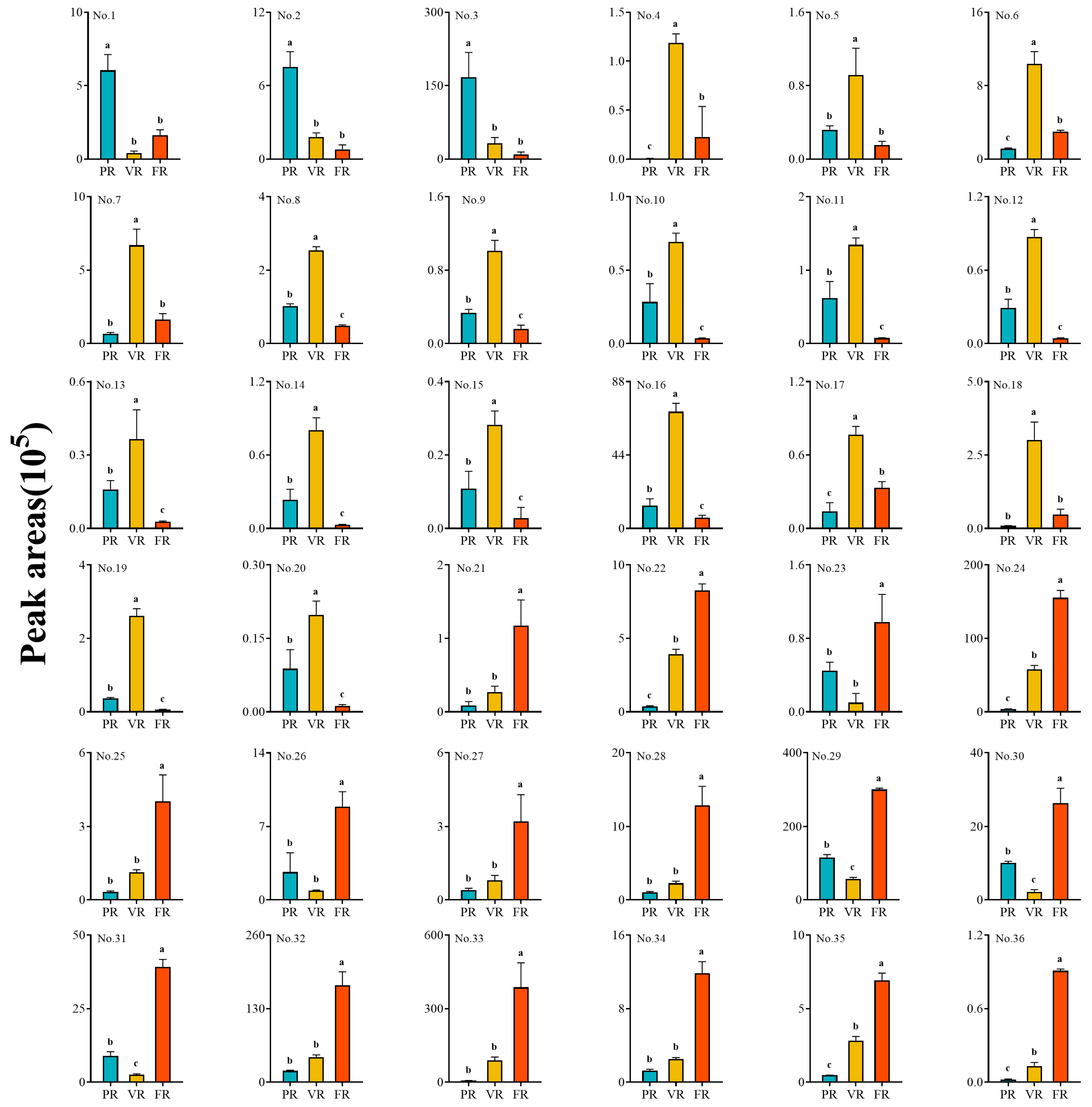

3.6. Key Differences in Sugar and Acid Between ‘Fengtang’ Plums at Different Developmental Stages

To identify common and stage-specific metabolites that may drive sugar–acid dynamics, Venn analysis was performed, revealing 36 shared differential metabolites across all three comparisons (

Figure 5A). These included 14 amino acids and derivatives, 14 phenolic acid compounds, three nucleotides and derivatives, and five sugar compounds (

Table 2). Of these, compounds

1–

3 (Asp-His-Asn, Arg-Gly, and Pro-Asp) belong to the amino acid and derivative category. Their peak areas in the PR stage are significantly higher than in the VR and FR stages, demonstrating clear stage-specific accumulation characteristics (

Figure 6).

Further analysis revealed that the peak area of compounds

4–

20 in the VR stage exhibited significant enrichment, which was notably higher than in the PR and FR stages (

Figure 6). This group of differential metabolites includes nine amino acids and their derivatives (Glu-Phe, L-Methionine, DL-Methionine, Leu-Asp, N-Acetyl-L-Arginine, N-Acetyl-L-Methionine, 7-Hydroxy-Tryptophan, Asp-Ile-Leu, and L-Leucyl-L-Leucine), three nucleotides and their derivatives (N7-Methylguanosine, Isoguanine, Guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate), and four phenolic acid compounds (Benzoylmalic acid, 1-O-Galloyl-4-O-p-Coumaroyl-β-D-glucose, 4-Hydroxybenzoylmalic acid, Syringic acid).

In addition, the peak area of compounds

21–

36 in the FR stage is significantly higher than in the PR and VR stages, with phenolic acid compounds dominating (

Figure 6). These include Calceolarioside B*, Homophthalic acid, 1-O-Caffeoyl-β-D-glucose, 4-Methoxyphenylpropionic acid, Anthranilate-1-O-Sophoroside, 2-β-D-Glucopyranosyloxy-4-methoxy-cis-cinnamic acid, 6-O-p-Coumaroyl-β-D-glucose, 6-O-Feruloyl-β-D-glucose, Grevilloside F, 1-O-Cinnamoyl-β-D-glucose. Amino acids and their derivatives only contain L-Glutamyl-L-Tyrosine. Carbohydrate compounds include Laminaran, Solatriose, D-Sorbitol, D-Melezitose, Raffinose*.

3.7. Metabolic Pathway Analysis of Differential Metabolites in ‘Fengtang’ Plum Fruits at Different Developmental Stages

To contextualize the observed metabolite changes within broader metabolic networks, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed on the differentially accumulated sugars and acids. This study used the KEGG database, a core platform for analyzing metabolic networks, to integrate multi-omics data analysis methods and systematically elucidate the functional annotation characteristics of differentially expressed glycan metabolites, as well as the key metabolic pathways in which they are involved, at the three developmental stages (PR, VR, and FR) of ‘Fengtang’ plums fruit. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that the selected glycolic acid differential metabolites were significantly enriched in 15 core pathways covering key nodes of plant physiological metabolism in the three developmental stage comparison groups of PR vs. VR, VR vs. FR, and FR vs. PR (

Figure 5B–D). These pathways include those related to plant hormone signal transduction, which regulates growth and development; glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, which is central to energy metabolism; carbon metabolism, which is important for material transformation; purine metabolism, which is related to nucleic acid metabolism; and the citric acid cycle (also known as the tricarboxylic acid cycle), which is a key link in energy production. Important branches of sugar metabolism were also identified, including the metabolism of sugars and mannose, pyruvate metabolism, and galactose metabolism. During the developmental transition stage from PR to VR, the pathway enrichment of glycolic acid metabolites shows significant stage specificity. This is mainly reflected in the enrichment of specific pathways, such as hexose conversion (fructose and mannose metabolism), oligosaccharide catabolism (galactose metabolism), the regulation of secondary metabolism (biosynthesis of various plant secondary metabolites), and pathways closely related to energy metabolism (the pentose phosphate pathway, the citric acid cycle, and pyruvate metabolism), as well as amino acid metabolism (cysteine and methionine metabolism). This suggests that coordinated regulation of primary and secondary metabolism plays an important role during this developmental transition period. Of particular importance is the finding from cross-group comparative analysis that the five metabolic pathways of fructose and mannose, pyruvate, galactose, D-amino acids, and 2-oxo acids were all stably present in the three control groups. This reveals their core role in maintaining glycolic acid metabolism homeostasis throughout the fruit’s entire development process. Fructose and mannose metabolism, along with galactose metabolism, constitute key branches of the hexose metabolic network. Pyruvate metabolism connects glycolysis to the tricarboxylic acid cycle, while D-amino acid and 2-oxy-carboxylic acid metabolism indirectly influence the balance of the carbon skeleton through amino acid conversion. Together, these pathways constitute the core metabolic network modules that support the accumulation of sugar and acid in fruits and the formation of their quality.

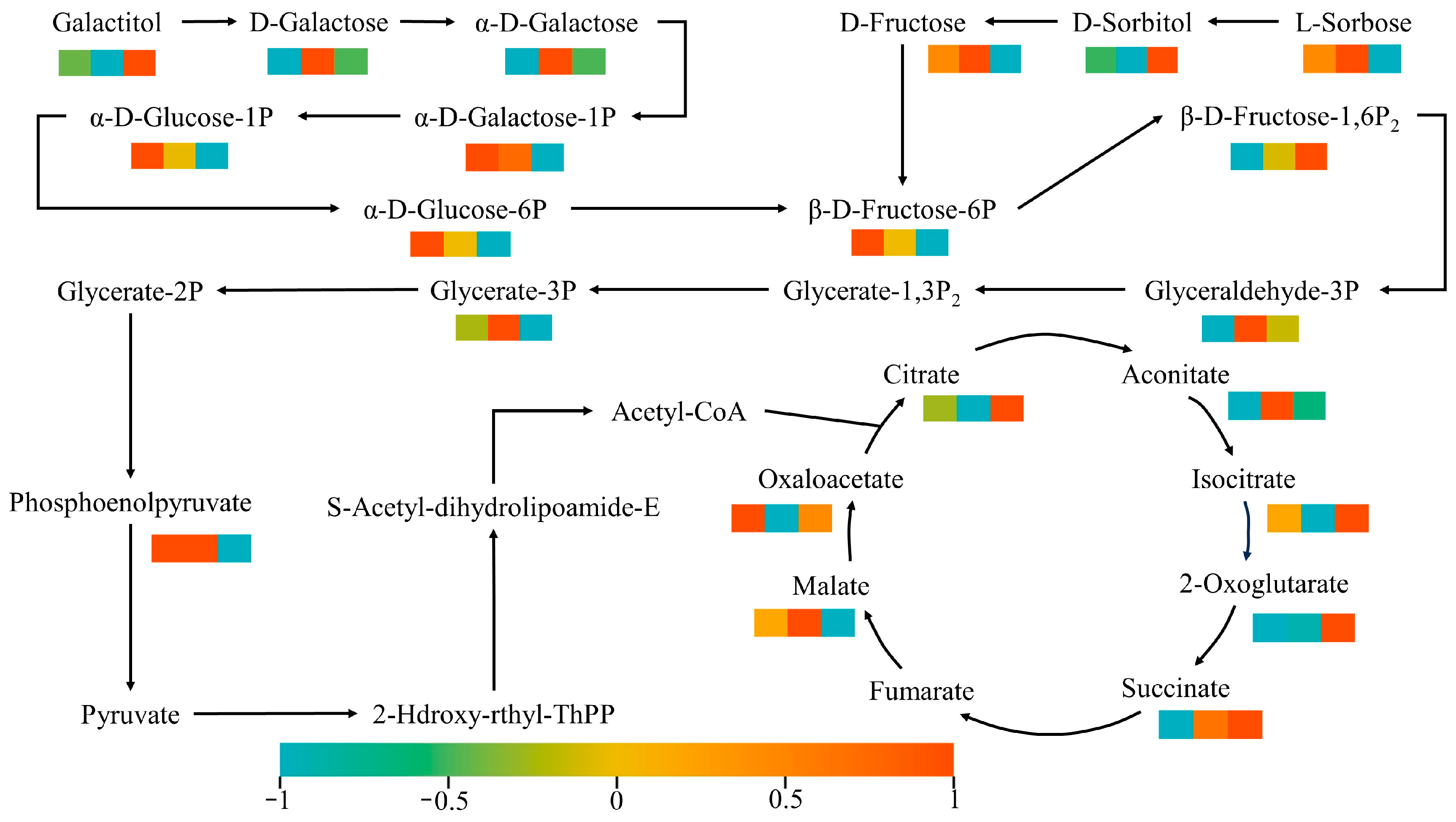

3.8. Analysis of Sugar–Acid Metabolic Mechanisms in ‘Fengtang’ Plums at Different Developmental Stages

To gain a deeper understanding of how glycolic acid metabolites accumulate differently at various stages of ‘Fengtang’ plums development, we conducted metabolomics analyses on four pathways in the carbon metabolism network: fructose and mannose metabolism, galactose metabolism, glycolysis, and the TCA cycle (

Figure 7).

Analysis of the fructose and mannose metabolic pathways indicates significant metabolic flux reprogramming at several key nodes, such as the conversion of galactol to D-galactose and α-D-galactose. Consider, for example, the mutual conversion of D-fructose and D-sorbitol. The steady-state equilibrium originally maintained is disrupted, and the flux ratio shows a significant shift. In the galactose metabolic pathway, the conversion process from α-D-glucose-1-phosphate to α-D-galactose-1-phosphate reveals dynamic fluctuations in the abundance of intermediate metabolites, indicating the dynamic regulatory mechanism of this metabolic network. Analysis of the glycolytic pathway shows that changes in the abundance of metabolites such as 2-phosphoglyceric acid and phosphoenolpyruvate directly reflect cellular energy metabolism response patterns. Additionally, changes in the peak areas of key regulatory node metabolites, such as 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde, further indicate the activation status of the glycolytic signalling system. In the tricarboxylic acid cycle, abnormal accumulation of key intermediate metabolites such as citric acid and oxaloacetic acid indicates reconstruction of the energy metabolism and material synthesis network.

Overall, the metabolism of fructose, mannose, and galactose mainly involves disturbances to the metabolism of carbohydrate precursors, such as monosaccharides (D-galactose) and phosphorylated sugars (α-D-glucose-6-phosphate). The glycolytic pathway is characterized by changes in the abundance of metabolites related to energy production. In contrast, the tricarboxylic acid cycle is associated with the coordinated regulation of the supply of precursors for substance synthesis and energy generation. These findings reveal the differences in the regulation of carbohydrate transport and energy reserve systems among various varieties at the molecular level. Significant species-specific regulatory mechanisms have been identified in key biological processes involved in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, such as the generation of acetyl-CoA and the transformation of core intermediate metabolites. This study provides an important theoretical basis for the in-depth molecular analysis of phenotypic differences in sugar–acid metabolism at the various developmental stages of the ‘Fengtang’ plum.

5. Conclusions

This study utilized metabolomics technology to systematically trace the sugar–acid metabolism trajectories of ‘Fengtang’ plum fruits at three key developmental stages. The results show that, at the FR stage, the ‘Fengtang’ plum exhibits a characteristic high-sugar, low-acid phenotype. Its TSS content is much higher than that of common plum varieties, and the sugar–acid ratio rises to 43.8, which gives it its unique sweet and less astringent flavor. A total of 36 core differential metabolites were identified, primarily phenolic acids, amino acid derivatives, and soluble sugars. Enrichment analysis of the KEGG pathway indicates that fructose–mannose metabolism, galactose metabolism, and the TCA cycle are the key networks determining the sugar–acid balance. These identified core metabolites and key metabolic pathways (e.g., fructose–mannose metabolism and TCA cycle) provide valuable candidate targets for molecular marker-assisted selection or genetic engineering aimed at optimizing sugar–acid composition in future plum breeding programs. Once the fruit has reached maturity, oligosaccharides such as raffinose and triose accumulate rapidly, potentially driving the efficient transport and storage of sugars into vacuoles by regulating cell osmotic potential and supplementing the carbon skeleton. These findings reveal the metabolic network mechanisms underlying the formation of ‘Fengtang’ plum’s high-quality sugars, providing a new theoretical basis for its precise cultivation and post-harvest quality maintenance.