Phenotypic Evaluation and Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Cold Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Evaluation of Cold Tolerance

2.3. Genotype Data and GWAS Analysis

2.4. Candidate Gene Prediction

2.5. Qrt-Pcr Verification

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Cold Resistance at Seedling Stage Across All Maize Materials

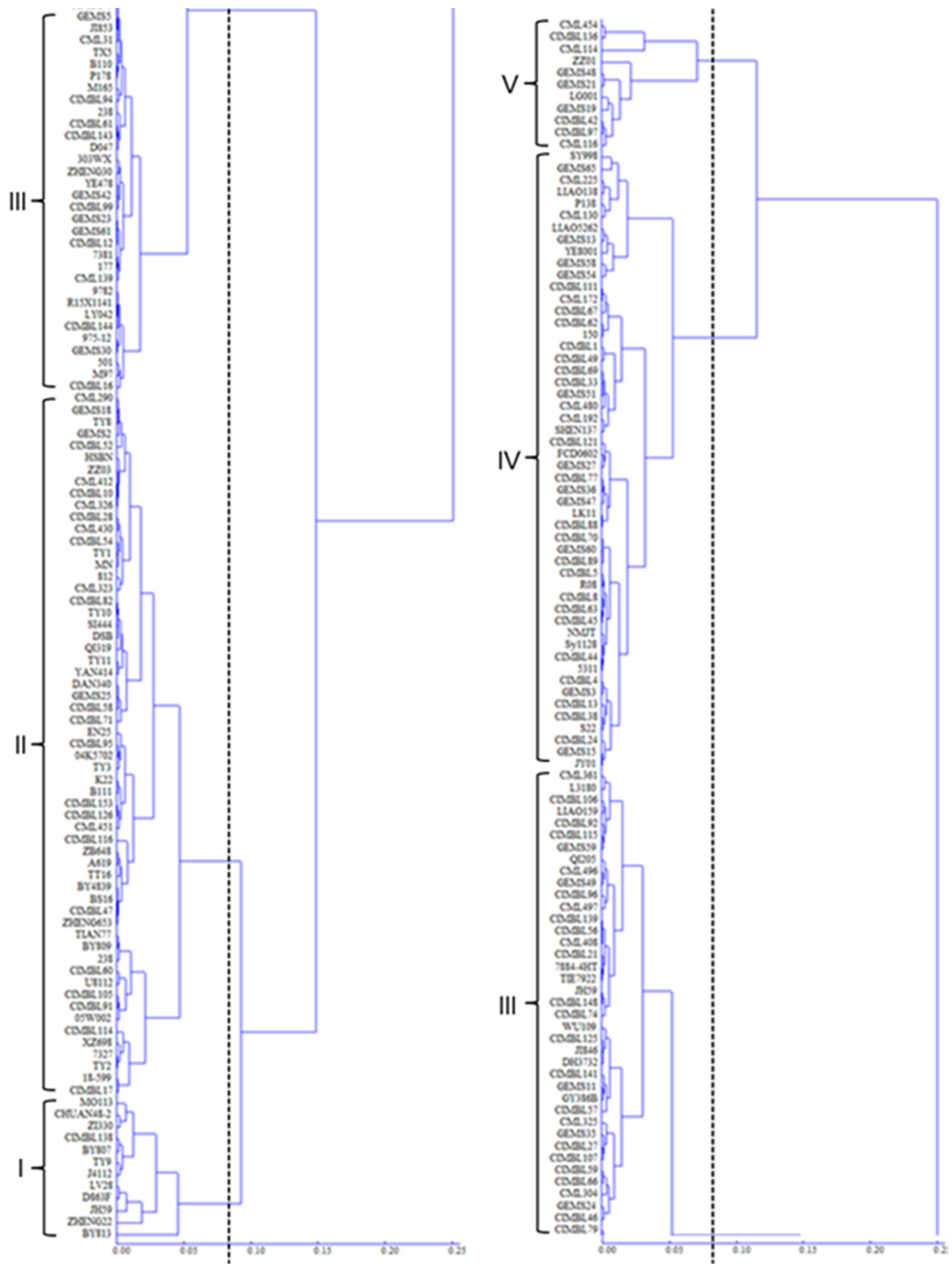

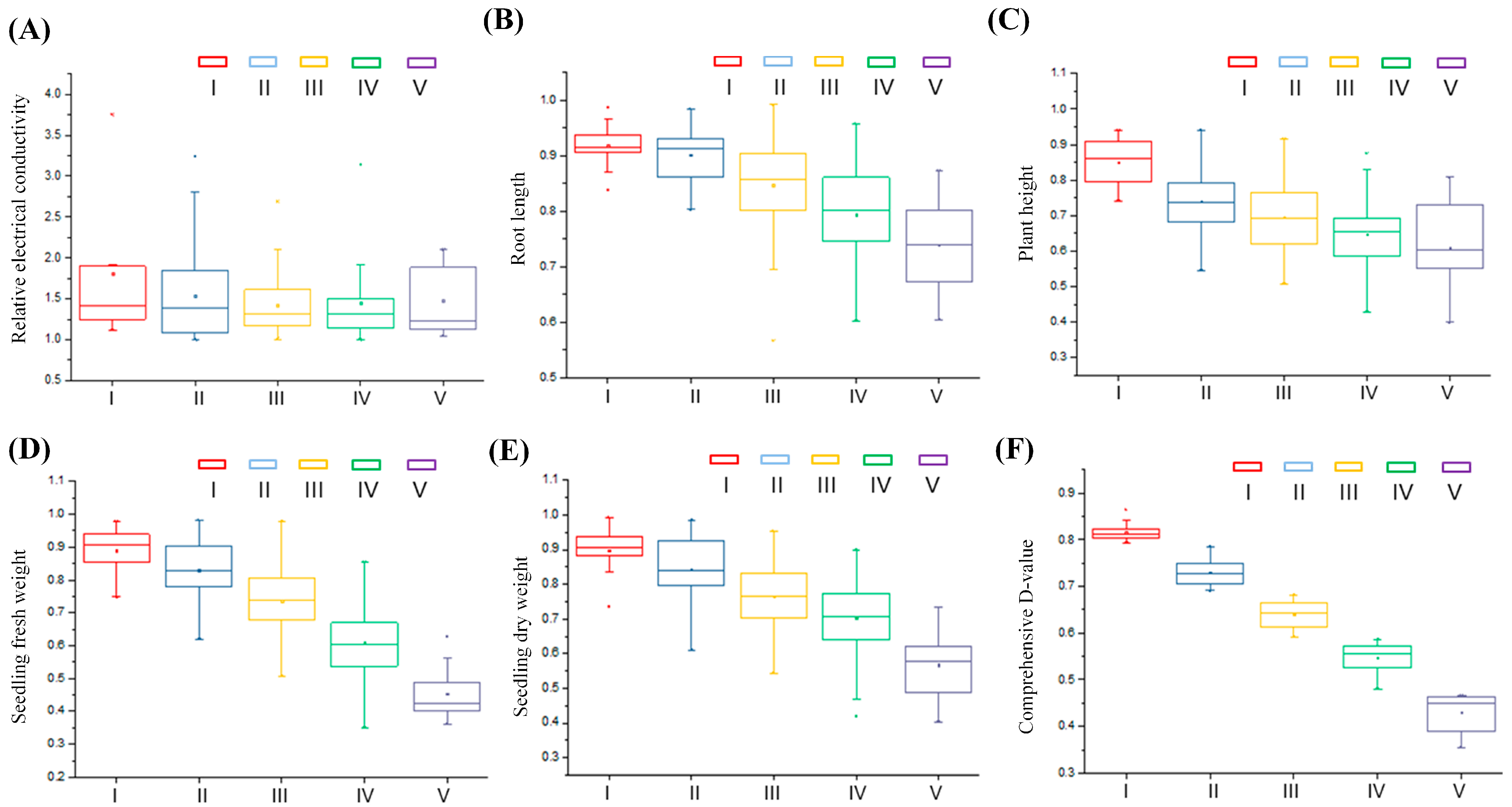

3.2. Cold Tolerance Classification and Cluster Analysis of Materials

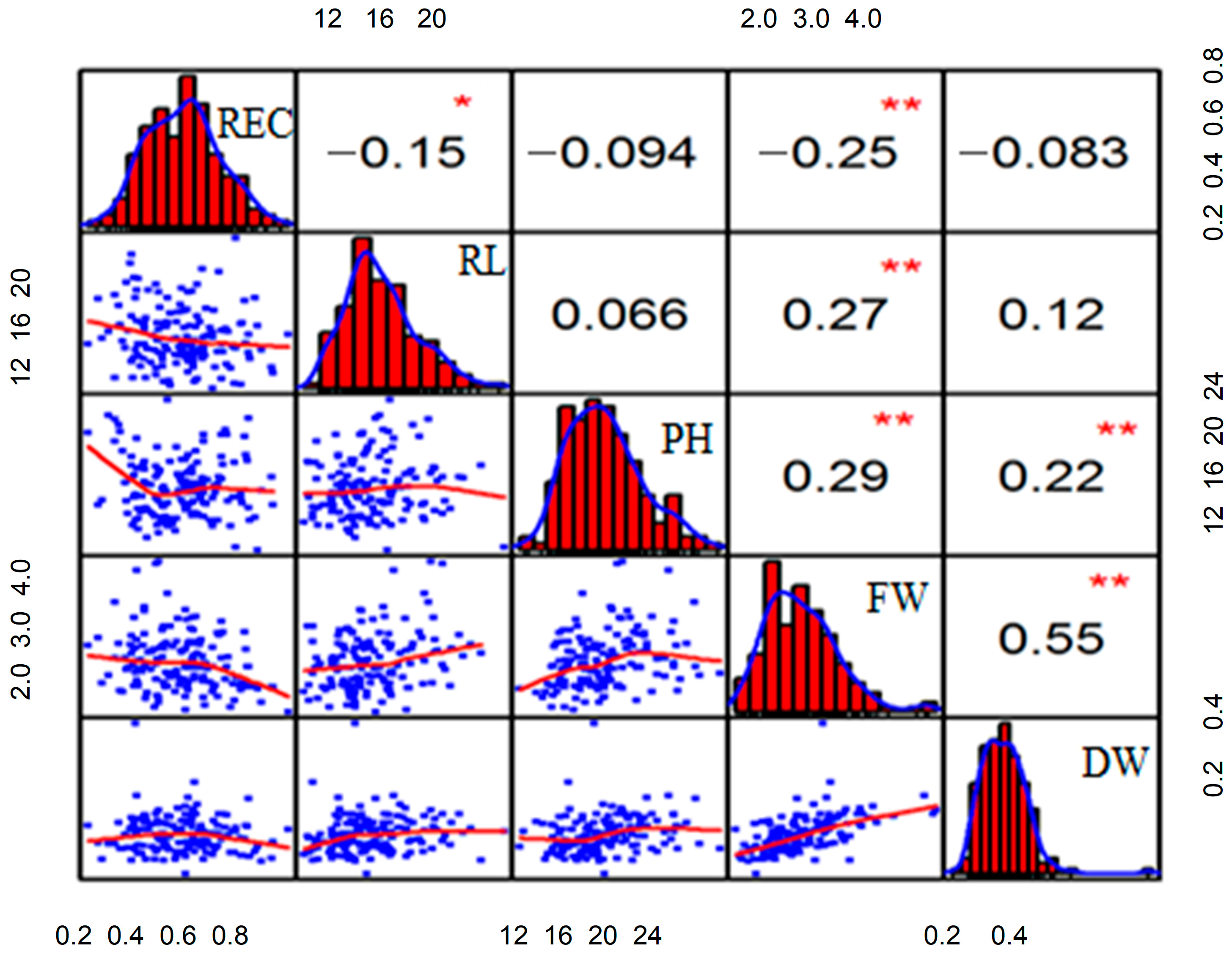

3.3. Correlation Analysis of All Traits

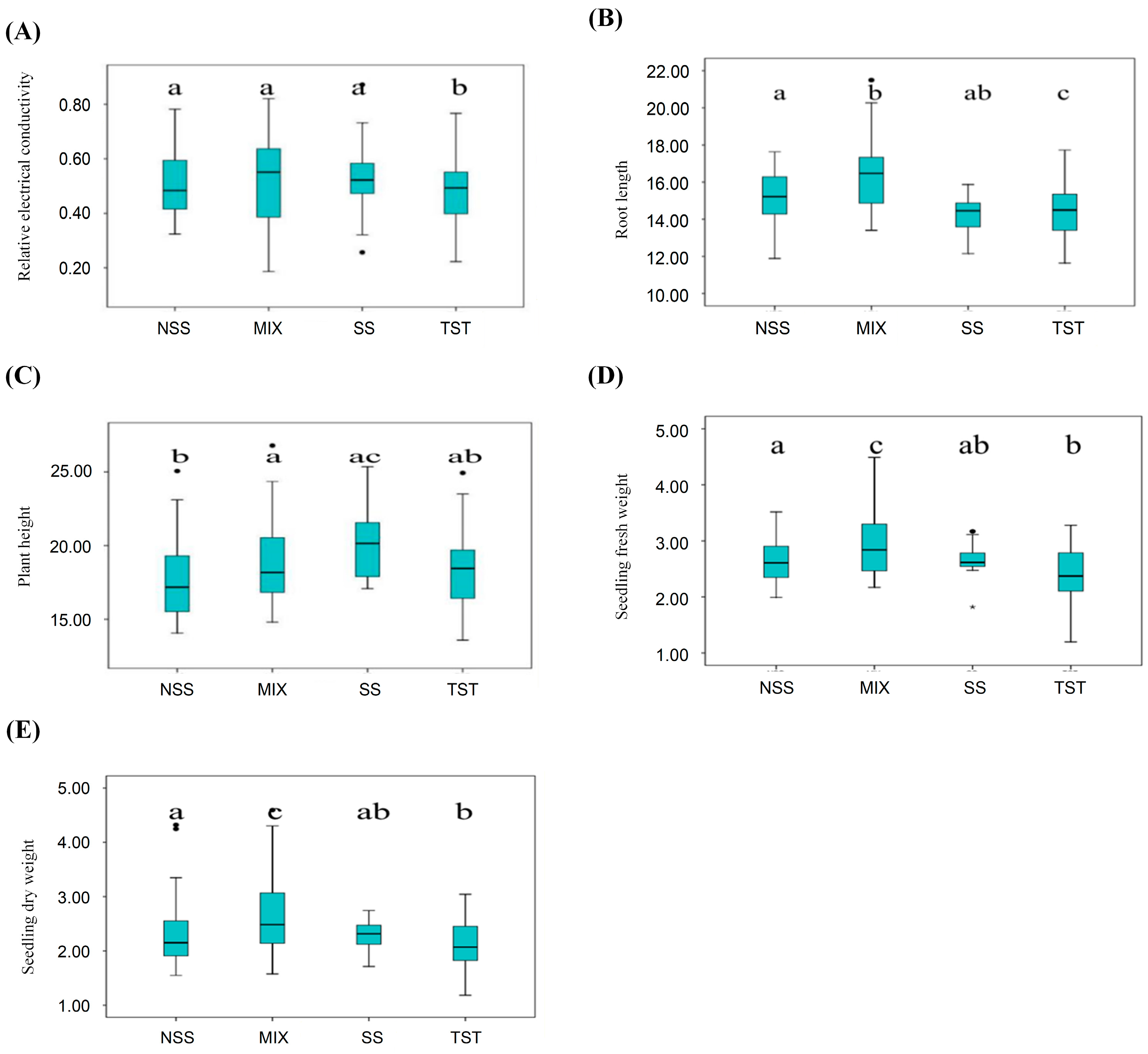

3.4. Analysis of Phenotypic Variation Among Different Subpopulations

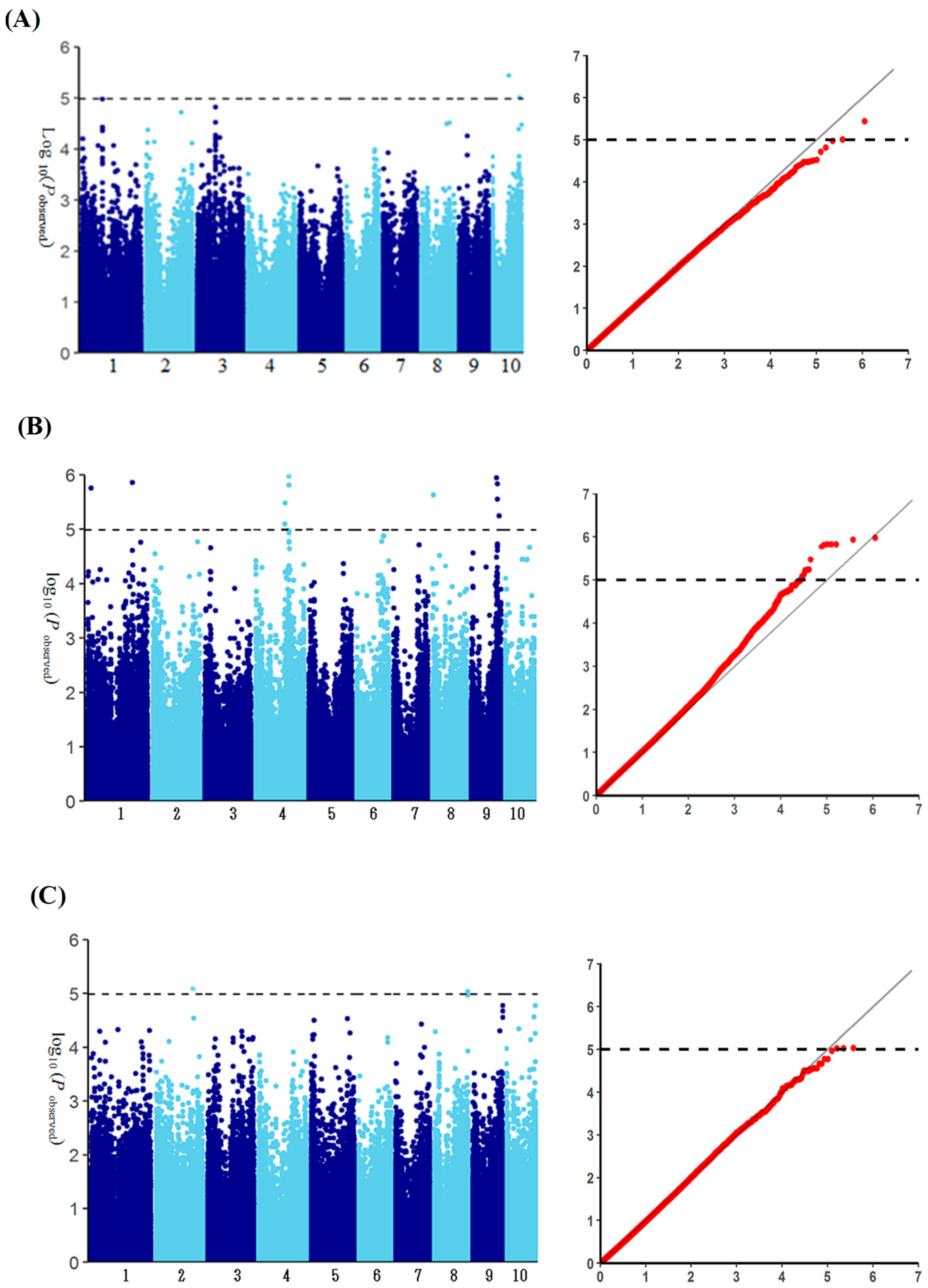

3.5. Genome-Wide Association Analysis

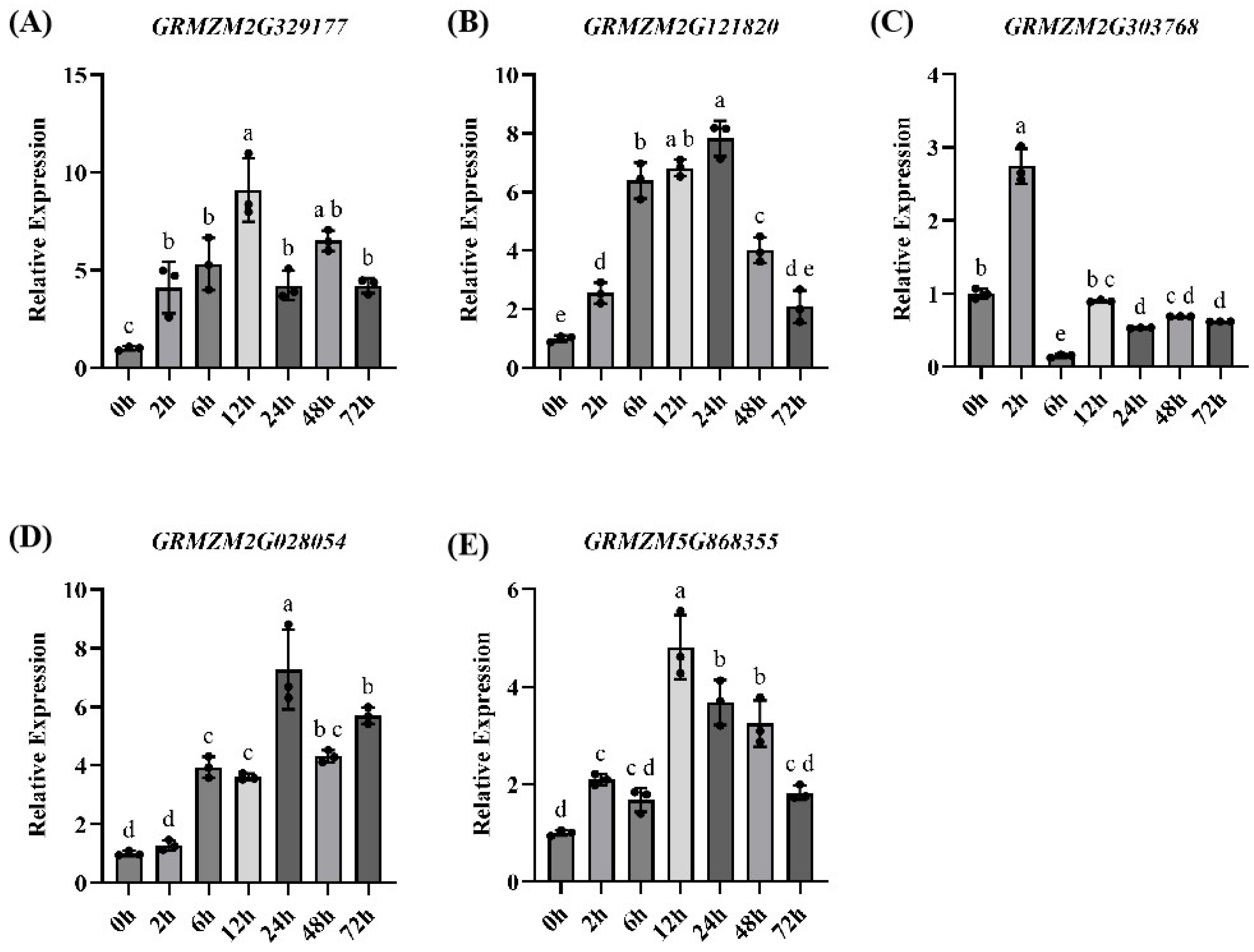

3.6. Screening and Characterization of Candidate Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, C.; Niu, Y.; Chao, W.; He, W.; Wang, Y.; Mao, T.; Bai, X. Understanding and Comprehensive Evaluation of Cold Resistance in the Seedlings of Multiple Maize Genotypes. Plants 2022, 11, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkowiak, A.; Jończyk, M.; Jarochowska, E.; Biecek, P.; Trzcinska-Danielewicz, J.; Leipner, J.; Fronk, J.; Sowiński, P. Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of response to low temperature reveals candidate genes determining divergent cold-sensitivity of maize inbred lines. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 85, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, A.; Wen, D.; Zhang, C. Maize seed germination under low-temperature stress impacts seedling growth under normal temperature by modulating photosynthesis and antioxidant metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 843033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, D.; Di, H.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Dong, L.; et al. Identification of candidate tolerance genes to low-temperature during maize germination by GWAS and RNA-seqapproaches. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, W.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, D.; Pan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 2015, 160, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Huang, Y. Global warming over the period 1961–2008 did not increase high-temperature stress but did reduce low-temperature stress in irrigated rice across China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Yaling, C.; Chu, G.; Wang, M. Low-temperature tolerance and transcriptome analyses during seed germination of Anabasis aphylla. J. Plant Interact. 2019, 14, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Lv, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Mai, J.; Wan, X.; Liu, P. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics analysis during seed germination of waxy corn under low temperature stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, C.; Gong, S.; Yan, S.; Li, G.; Wang, M.; Ren, H.; Guan, H.; et al. Genome-wide association study identified multiple genetic loci on chilling resistance during germination in maize. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.; Tan, J.; Feng, H.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, M.; Luo, H.; Deng, Z. Integrative proteome and phosphoproteome profiling of early cold response in maize seedlings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.S.; Rice, B.R.; Shenstone, E.M.; Lipka, A.E.; Jamann, T.M. Genome-wide analysis and prediction of resistance to goss’s wilt in maize. Plant Genome 2019, 12, 180045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikha, K.; Shahi, J.P.; Vinayan, M.T.; Zaidi, P.H.; Singh, A.K.; Sinha, B. Genome-wide association mapping in maize: Status and prospects. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Peng, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.; Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Han, Y.; Chai, Y.; Guo, T.; Yang, N.; et al. Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Hu, W.; Duan, L.; Feng, Y.; Qiu, F.; Yue, B. Genome-wide association analysis of ten chilling tolerance indices at the germination and seedling stages in maize: Genome-wide association analysis of chilling tolerance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2013, 55, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, T.; Meng, Z.; Yue, R.; Lu, S.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Meng, H.; Sun, Q. Genome wide association analysis for yield related traits in maize. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Shi, Y.; Guo, L.; Fu, D.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Yang, X.; Zuo, J.; et al. A natural variant of COOL1 gene enhances cold tolerance for high-latitude adaptation in maize. Cell 2025, 188, 1315–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.Y.; Song, Y.Y.; Bao, D.; Meng, L.Z.; Di, H.; Zhang, L.; Dong, L.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Li, C.X.; et al. ZmBARK1 as a low-temperature tolerance gene in maize germination. Crop J. 2025, 13, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Sun, Y.D.; Xing, J.Y.; Zhan, L.; Li, X.J.; Huang, J.; Zhao, M.H.; Guo, Z.F. Transcriptomic and functional analyzes reveal that the brassinosteroid insensitive 1 receptor (OsBRI1) regulates cold tolerance in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 208, 108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, G.; Rodríguez, F.M.; Pacheco, A.; Burgueño, J.; Crossa, J.; Vargas, M.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Lopez-Cruz, M.A. META-R: A software to analyze data from multi-environment plant breeding trials. Crop J. 2020, 5, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.H.; Gao, S.B.; Xu, S.T.; Zhang, Z.X.; Prasanna, B.M.; Li, L.; Li, J.S.; Yan, J.B. Characterization of a global germplasm collection and its potential utilization for analysis of complex quantitative traits in maize. Mol. Breed. 2020, 28, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Yu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, A.; Cui, Z.; Dong, X.; Fan, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; et al. A genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of the metaxylem vessel number in maize brace roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 847234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, D.; Xue, M.; Li, G.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Duan, L.; et al. Genome-wide association study of salt tolerance at the seed germination stage in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). Genes 2022, 13, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xing, H.; Zeng, W.; Xu, J.; Mao, L.; Wang, L.; Feng, W.; Tao, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; et al. Genome-wide association and differential expression analysis of salt tolerance in Gossypium hirsutum L. at the germination stage. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, R. CabHLH79 Acts Upstream of CaNAC035 to Regulate Cold Stress in Pepper. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fracheboud, Y.; Jompuk, C.; Ribaut, J.M.; Stamp, P.; Leipner, J. Genetic analysis of cold-tolerance of photosynthesis in maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 56, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, R.; Larsen, S.; Tan, J.; Whelan, J.; Makarevitch, I. QTL mapping of seedling tolerance to exposure to low temperature in the maize IBM RIL population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Hao, Y.; Kapoor, A.; Dong, C.H.; Fujii, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, J.K. A R2R3 type MYB transcription factor is involved in the cold regulation of CBF genes and in acquired freezing tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37636–37645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, S.; Oldroyd, G.E. GRAS-domain transcription factors that regulate plant development. Plant Signal. Behav. 2009, 4, 698–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, D.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, S.; Li, J.; et al. Genome-wide association studies identified three independent polymorphisms associated with α-tocopherol content in maize kernels. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, C.L.; Fu, Y.; Liao, Z.W.; Guo, P.Y.; Xiong, R.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, S.S.; Huang, J.Q.; Tang, H. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of pitaya (Hylocereus polyrhizus) HpLRR genes in response to Neoscytalidium dimidiatum infection. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhong, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, N.; Liu, J.; Ding, B.; Li, Z.; Kang, H.; Ning, Y.; et al. A fungal effector targets a heat shock-dynamin protein complex to modulate mitochondrial dynamics and reduce plant immunity. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, D.; Wang, C.; Ji, X.; Wang, Y. Tamarix hispida zinc finger protein ThZFP1 participates in salt and osmotic stress tolerance by increasing proline content and SOD and POD activities. Plant Sci. 2015, 235, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trait | Process Mode | Mean ± SD | Coefficient of Variation (%) | t-Value | Coefficient of Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC | CT | 0.59 ± 0.18 | 30.51 | −16.57 ** | 0.60 |

| CK | 0.42 ± 0.15 | 35.71 | |||

| PH (cm) | CT | 15.30 ± 3.10 | 20.26 | 32.85 ** | 0.75 |

| CK | 22.38 ± 7.11 | 31.77 | |||

| RL (cm) | CT | 14.35 ± 2.36 | 16.45 | 22.39 ** | 0.67 |

| CK | 17.02 ± 2.50 | 14.53 | |||

| FW (g) | CT | 2.36 ± 0.94 | 39.83 | 21.38 ** | 0.72 |

| CK | 3.25 ± 0.90 | 27.69 | |||

| DW (g) | CT | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 40.90 | 22.34 ** | 0.90 |

| CK | 0.28 ± 0.096 | 34.29 |

| Trait | Average Number | Amplitude of Variation | Coefficient of Variation | F-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC | 1.53 ± 0.69 | 0.47–3.75 | 45.10 | 46.23 ** |

| PH (cm) | 0.70 ± 0.10 | 0.40–0.94 | 14.29 | 3.58 ** |

| RL (cm) | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.57–0.99 | 10.59 | 97.05 ** |

| FW (g) | 0.72 ± 0.15 | 0.35–0.98 | 20.83 | 1.61 * |

| DW (g) | 0.77 ± 0.13 | 0.34–0.99 | 16.88 | 70.75 ** |

| Index | 0 < CC < 0.2 | 0.2 < CC < 0.4 | 0.4 < CC < 0.6 | 0.6 < CC < 0.8 | 0.8 < CC < 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | |

| RL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.96 | 49 | 23.44 | 158 | 75.60 |

| PH | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.48 | 33 | 15.79 | 135 | 64.59 | 40 | 19.14 |

| FW | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.44 | 42 | 20.10 | 89 | 42.58 | 75 | 35.89 |

| DW | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.48 | 19 | 9.09 | 101 | 48.33 | 88 | 42.11 |

| Index | 1 < CC < 1.5 | 1.5 < CC < 2 | 2 < CC < 2.5 | 2.5 < CC < 3 | 3 < CC < 4 | |||||

| Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | Times | Freq. (%) | |

| REC | 140 | 66.98 | 41 | 19.62 | 15 | 7.18 | 5 | 2.39 | 8 | 3.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.; García-Caparros, P.; Yin, X.; Sun, D.; Su, Y.; Sun, H.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Guo, Z. Phenotypic Evaluation and Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Cold Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Maize. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2842. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122842

Cheng Y, García-Caparros P, Yin X, Sun D, Su Y, Sun H, Ruan Y, Chen S, Liu J, Guo Z. Phenotypic Evaluation and Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Cold Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Maize. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2842. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122842

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yishan, Pedro García-Caparros, Xiaohong Yin, Dongxian Sun, Yunhua Su, Han Sun, Yanye Ruan, Shuisen Chen, Jun Liu, and Zhifu Guo. 2025. "Phenotypic Evaluation and Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Cold Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Maize" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2842. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122842

APA StyleCheng, Y., García-Caparros, P., Yin, X., Sun, D., Su, Y., Sun, H., Ruan, Y., Chen, S., Liu, J., & Guo, Z. (2025). Phenotypic Evaluation and Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Cold Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Maize. Agronomy, 15(12), 2842. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122842