Quantifying Manure’s Fertilizer Nitrogen Equivalence to Optimize Chemical Fertilizer Substitution in Potato Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site Description

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measurements and Analytical Methods

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Calculations

3. Results

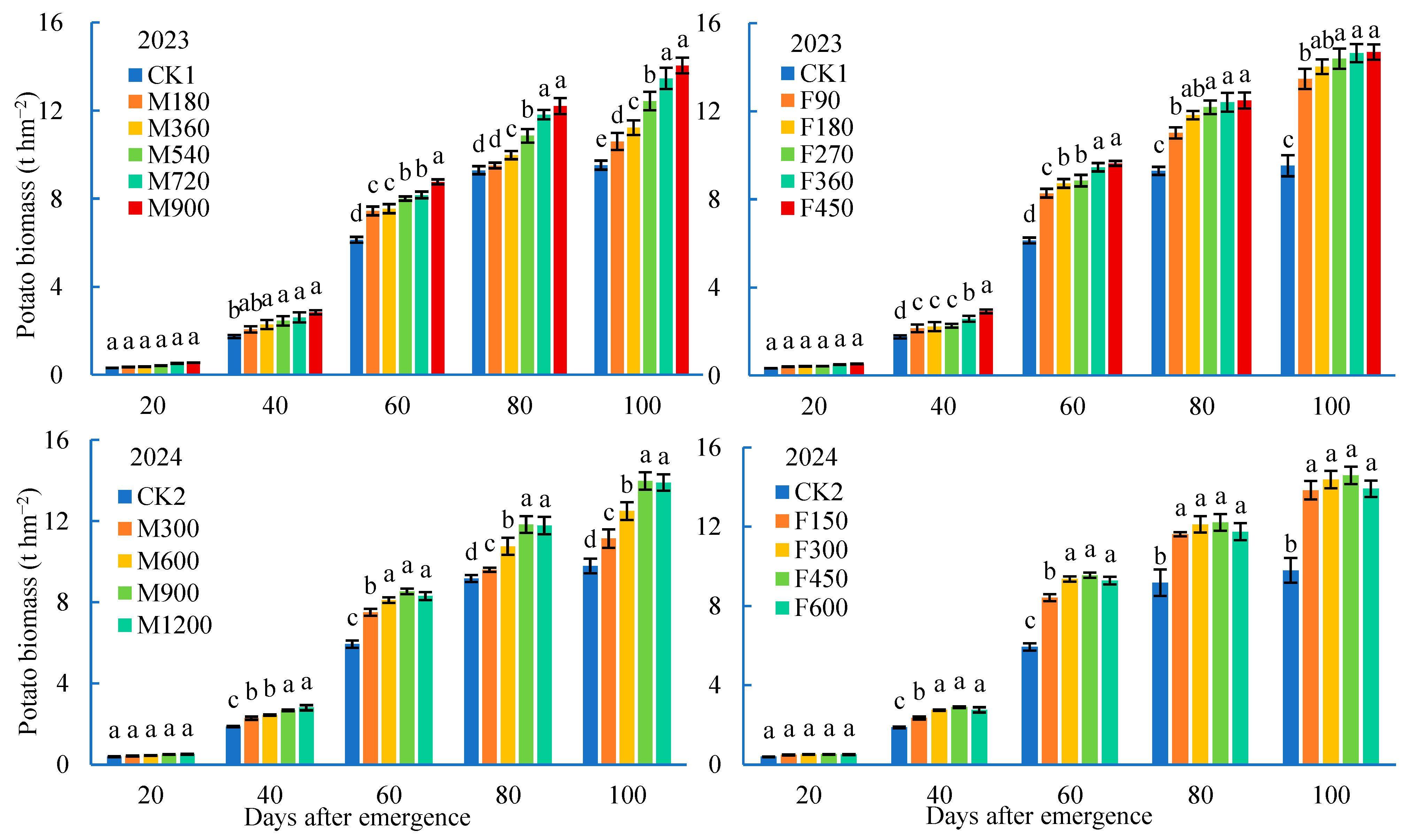

3.1. Plant Growth and Tuber Yield

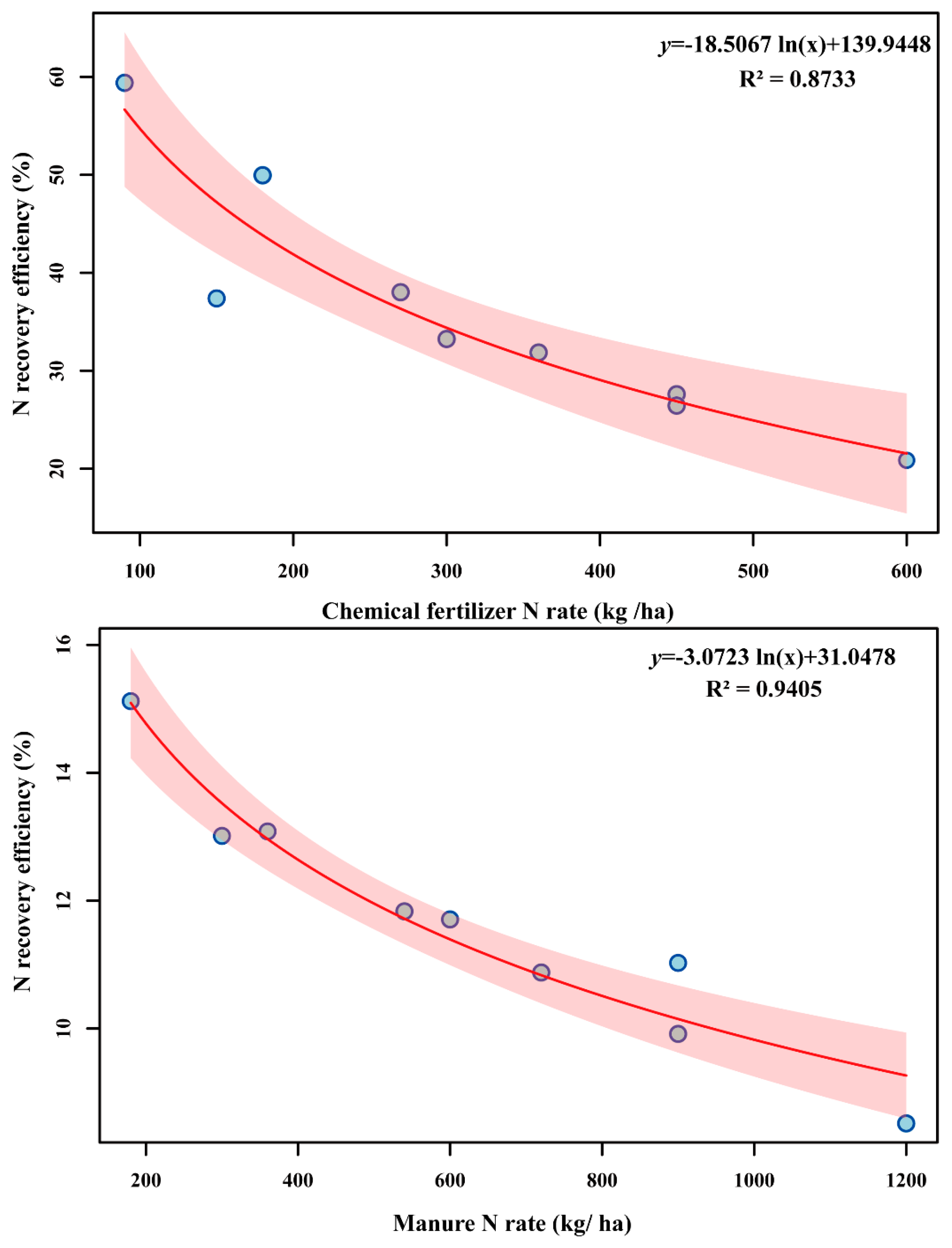

3.2. Nitrogen Uptake by Potato Plants

3.3. Fertilizer Nitrogen Equivalence (FNE) of Sheep Manure in Potato Production

4. Discussion

4.1. Yield and N Uptake Responses and Implications for Manure–Fertilizer Substitution

4.2. Stability of FNE Across Manure Gradients and Its Mechanistic Interpretation

4.3. Divergence Between Uptake-Based and Yield-Based FNE and Constraints of Potato Physiology

4.4. FNE Patterns Across Temperature Regimes and Manure Types: Contextualizing the Findings

4.5. Agronomic Implications for Integrated N Management in Potato Systems

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FNE | Fertilizer nitrogen equivalence |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NUE | Nitrogen use efficiency |

| DAE | Days after emergence |

| ANOVA | Data were analyzed using analysis of variance |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| RE | Recovery efficiency |

References

- van Zwieten, L. The long-term role of organic amendments in addressing soil constraints to production. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 111, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Ma, W.; Velthof, G.L.; Hou, Y.; Oenema, O.; Zhang, F. Benefits and trade-offs of replacing synthetic fertilizers by animal manures in crop production in China: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Sun, Y.; Zou, H.; Li, D.; Lu, C.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, W. Effect of replacing synthetic nitrogen fertilizer with animal manure on grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in China: A meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1153235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, M.; Jemberie, M.; Yeshiwas, T.; Aklile, M. Integrated application of compound NPS fertilizer and farmyard manure for economical production of irrigated potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) in highlands of Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1724385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechassa, N.; Schenk, M.K.; Claassen, N.; Steingrobe, B. Phosphorus efficiency of cabbage (Brassica oleraceae L. var. capitata), carrot (Daucus carota L.), and potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plant Soil 2003, 250, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, K. Physiology of the Potato: New Insights into Root System and Repercussions for Crop Management. Potato Res. 2008, 51, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, R.; Harris, P.M.; Baba, M.R. Investigations into the mode of action of farmyard manure. I. The influence of soil moisture conditions on the response of main crop potatoes to farmyard manure. J. Agric. Sci. 1965, 64, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standford, G. Assessment of soil nitrogen availability. In Nitrogen in Agricultural Soils; Stevenson, F.J., Ed.; Agronomy Monograph; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; Volume 22, pp. 651–688. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.K.; Sharma, R.C.; Trehan, S.P. Integrated nutrient management by using farmyard manure and fertilizers in potato–sunflower–paddy rice rotation in the Punjab. J. Agric. Sci. 2001, 137, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikumar, T.S.; Öckerman, P.A. The effects of fertilization and manuring on the content of some nutrients in potato. Food Chem. 1990, 37, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, L.; Su, H.; Yu, H.; Fu, Q.; Fan, S.; Cheng, Y. Effects of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers on Growth and Tuber Yield of Potato. Soil 2020, 52, 862–866, (In Chinese with English Abstract and Title). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Effect of organic fertilizer combined with inorganic fertilizer on growth, yield and quality of potato. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2020, 49, 32–39, (In Chinese with English Abstract and Title). [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, L.S. Animal manure fertiliser value, crop utilisation and soil quality impacts. In Animal Manure Recycling: Treatment and Management; Sommer, S.G., Christensen, M.L., Schmidt, T., Jensen, L.S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 295–328. [Google Scholar]

- Gutser, R.; Ebertseder, T.; Weber, A.; Schraml, M.; Schmidhalter, U. Short-term and residual availability of nitrogen after long-term application of organic fertilizers on arable land. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.J.; Uenk, D.; Hilhorst, G.J. Long-term nitrogen fertiliser replacement value of cattle manures applied to cut grassland. Plant Soil. 2007, 299, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montealegre, J.P.G.; Charles, W.; Richard, F.; Timothy, S.; Richard, L.; James, S. Fertilizer equivalence of organic nitrogen applied in beef cattle manure. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2019, 114, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curless, M.A.; Kelling, K.A.; Speth, P.E. Nitrogen and phosphorus availability from liquid dairy manure to potatoes. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikula, D.; ten Berge, H.F.M.; Goedhart, P.W.; Schröder, J.J. Apparent nitrogen fertilizer replacement value of grass–clover leys and of farmyard manure in an arable rotation. Part II: Farmyard manure. Soil Use Manag. 2016, 32 (Suppl. S1), 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yuan, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Mi, G.; Zhao, B. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Replacement Value of Three Representative Livestock Manures Applied to Summer Maize in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerik, D.; Hof, E.; Hijbeek, R. Nitrogen fertilizer replacement values of organic amendments: Determination and prediction. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2024, 129, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Nitrogen–total. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Sparks, D.L., Page, A.L., Helmke, P.A., Loeppert, R.H., Soltanpour, P.N., Tabatabai, M.A., Johnston, C.T., Sumner, M.E., Eds.; Part 3: Chemical Methods; SSSA Book Set. 5; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1085–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, J.M.; Campbell, G.S. Canopy structure. In Plant Physiological Ecology: Field Methods and Instrumentation; Pearcy, R.W., Ehleringer, J.R., Mooney, H.A., Rundel, P.W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 301–325. [Google Scholar]

- Curless, M.A.; Kelling, K.A. Preliminary estimates of nitrogen availability from liquid dairy manure to potato. HortTechnology 2003, 13, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffland, E.; Kuyper, T.W.; Comans, R.N.J.; Creamer, R.E. Eco-functionality of soil organic matter: Linking OM quality to ecosystem functions. Plant Soil. 2020, 455, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, B.; Schnecker, J.; Alves, R.J.E.; Barsukov, P.; Bárta, J.; Čapek, P.; Gentsch, N.; Gittel, A.; Guggenberger, G.; Lashchinskiy, N.; et al. Input of easily available organic C and N stimulates microbial decomposition of soil organic matter in arctic permafrost soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 75, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yuan, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Mi, G.; Zhao, B. Relative substitution equivalent of nitrogen from livestock manure for chemical nitrogen fertilizer in a winter wheat season. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2023, 29, 421–434, (In Chinese with English Abstract and Title). [Google Scholar]

- Patni, N.K.; Culley, J.L.B. Corn Silage Yield, Shallow Groundwater Quality and Soil Properties Under Different Methods and Times of Manure Application. Trans. ASABE 1989, 32, 2123–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimande, P.; Arrobas, M.; Correia, C.M.; Rodrigues, M.Â. Sewage sludge showed high agronomic value, releasing nitrogen faster than farmyard manure. Soil Use Manag. 2025, 41, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Chemical Properties | Manure Nutrient Content % | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | pH | Organic Matter (g/kg) | Total N (g/kg) | Olsen P (mg/kg) | Exchangeable K (mg/kg) | N | P2O5 | K2O |

| 2023 | 7.8 | 24.2 | 2.10 | 16.8 | 126.4 | 2.34 | 0.42 | 1.52 |

| 2024 | 7.9 | 23.7 | 2.08 | 14.3 | 128.5 | 2.27 | 0.45 | 1.59 |

| Year | Treatments | Manure N (kg ha−1) | Urea N (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | CK | 0 | 0 |

| M180 | 180 | 0 | |

| M360 | 360 | 0 | |

| M540 | 540 | 0 | |

| M720 | 720 | 0 | |

| M900 | 900 | 0 | |

| F90 | 0 | 90 | |

| F180 | 0 | 180 | |

| F270 | 0 | 270 | |

| F360 | 0 | 360 | |

| F450 | 0 | 450 | |

| 2024 | CK | 0 | 0 |

| M300 | 300 | 0 | |

| M600 | 600 | 0 | |

| M900 | 900 | 0 | |

| M1200 | 1200 | 0 | |

| F150 | 0 | 150 | |

| F300 | 0 | 300 | |

| F450 | 0 | 450 | |

| F600 | 0 | 600 |

| Year | Treatments | Tuber Yield (t ha−1) | Tuber Number per Plant | Average Tuber Weight (kg Tuber−1) | Marketable Tuber Rate (%) | N Uptake by Potatoes (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | CK | 34.21 f | 4.13 a | 0.21 g | 84.69 d | 153.95 h |

| M180 | 37.43 e | 4.00 a | 0.23 f | 91.47 c | 181.17 g | |

| M360 | 39.48 de | 4.06 a | 0.24 ef | 89.50 c | 201.05 f | |

| M540 | 41.42 d | 4.13 a | 0.25 e | 92.92 bc | 217.85 e | |

| M720 | 45.38 c | 4.06 a | 0.28 d | 97.36 ab | 232.26 d | |

| M900 | 50.99 b | 4.10 a | 0.31 c | 95.95 ab | 243.20 c | |

| F90 | 46.09 c | 4.13 a | 0.21 g | 84.69 d | 207.41 ef | |

| F180 | 49.77 b | 3.67 a | 0.31 c | 96.31 ab | 243.87 c | |

| F270 | 51.32 b | 3.89 a | 0.32 bc | 97.68 a | 256.60 b | |

| F360 | 53.73 a | 3.89 a | 0.33 ab | 97.15 b | 268.65 a | |

| F450 | 54.59 a | 3.83 a | 0.35 a | 98.03 a | 272.95 a | |

| 2024 | CK | 35.64 e | 4.62 a | 0.19 f | 85.90 d | 160.37 f |

| M300 | 39.71 d | 4.52 a | 0.22 e | 87.28 d | 199.41 e | |

| M600 | 43.41 c | 4.48 a | 0.24 d | 91.17 c | 230.61 c | |

| M900 | 49.53 b | 4.27 a | 0.29 c | 93.73 b | 259.61 b | |

| M1200 | 49.05 b | 4.23 a | 0.29 c | 94.45 b | 262.57 b | |

| F150 | 48.10 b | 4.62 a | 0.19 f | 85.93 a | 216.45 d | |

| F300 | 52.02 a | 4.09 a | 0.29 c | 96.94 a | 260.10 b | |

| F450 | 53.69 a | 4.05 a | 0.32 b | 98.46 a | 284.57 a | |

| F600 | 51.91 a | 3.72 a | 0.36 a | 97.58 a | 285.51 a |

| Year | Manure N Rate (kg ha−1) | FNE (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on Total N Uptake | Based on N Uptake from Fertilizer | Based on Tuber Yield | Based on Tuber Yield Increase | ||

| 2023 | 180 | 18.07 | 28.35 | 8.49 | 12.59 |

| 360 | 22.16 | 27.55 | 10.92 | 12.89 | |

| 540 | 23.08 | 26.86 | 11.74 | 12.99 | |

| 720 | 23.37 | 26.39 | 16.37 | 17.18 | |

| 900 | 22.89 | 25.47 | 23.95 | 24.30 | |

| 2024 | 300 | 29.88 | 26.32 | 14.03 | 10.78 |

| 600 | 27.16 | 27.34 | 14.96 | 12.88 | |

| 900 | 30.62 | 30.14 | 20.74 | 18.45 | |

| 1200 | 24.24 | 23.78 | 14.82 | 13.18 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jia, L.; Fan, M. Quantifying Manure’s Fertilizer Nitrogen Equivalence to Optimize Chemical Fertilizer Substitution in Potato Production. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122817

Yu J, Zhu Z, Shi X, Qin Y, Chen Y, Jia L, Fan M. Quantifying Manure’s Fertilizer Nitrogen Equivalence to Optimize Chemical Fertilizer Substitution in Potato Production. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122817

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Jing, Zixing Zhu, Xiaohua Shi, Yonglin Qin, Yang Chen, Liguo Jia, and Mingshou Fan. 2025. "Quantifying Manure’s Fertilizer Nitrogen Equivalence to Optimize Chemical Fertilizer Substitution in Potato Production" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122817

APA StyleYu, J., Zhu, Z., Shi, X., Qin, Y., Chen, Y., Jia, L., & Fan, M. (2025). Quantifying Manure’s Fertilizer Nitrogen Equivalence to Optimize Chemical Fertilizer Substitution in Potato Production. Agronomy, 15(12), 2817. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122817